Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Room Where Averages Break

A peculiar phenomenon haunts the digital age - the way attempts at personalization lead deeper into standardization. The tools built to express individuality have become instruments of conformity, operating through "far-from-equilibrium conditions"[1], creating an illusion of endless possibility while enforcing subtle standardization.The mechanisms of this transformation operate through soft control, that gentle force that "applies a minimum amount of force, and modulates 'specification vs. creativity, closure and replicability vs. open-endedness and surprise'"[2]. This control manifests in systems where "being out of control does not mean to be beyond control"[3], crafting an environment of apparent freedom within carefully defined boundaries.

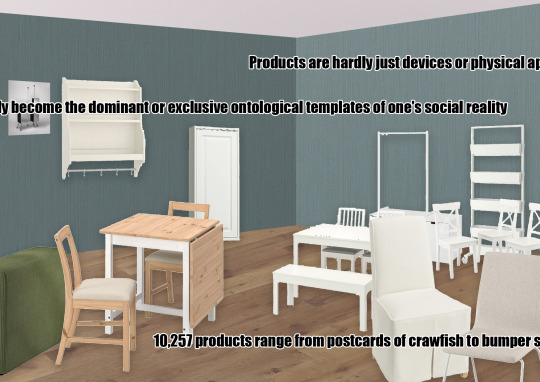

Digital spaces present themselves as infinitely customizable, yet they operate through "an imposed and inescapable uniformity to our compulsory labor of self-management"[4]. Users navigate these spaces experiencing "sudden and frequent shifts from absorption in a cocoon of control and personalization into the contingency of a shared world intrinsically resistant to control"[5]. These cocoons become comfortable prisons of curated content and predictable pleasures.The marketplace exemplifies this paradox, where "Products are hardly just devices or physical apparatuses, but various services and interconnections that quickly become the dominant or exclusive ontological templates of one's social reality"[6]. Modern services demonstrate this with their "10,257 products range from postcards of crawfish to bumper stickers featuring a piece of cheese"[7], all generated by "feeding some obscure database of natural images into product creator and waiting to see what sticks"[8].

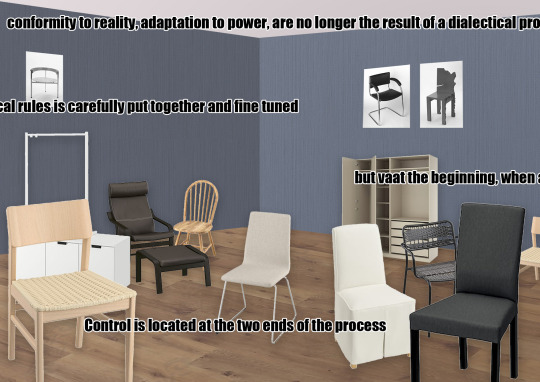

The infrastructure supporting this process reveals that "Control is located at the two ends of the process: at the beginning, when a set of local rules is carefully put together and fine tuned; and at the end, when a searching device or a set of aims and objectives aim at ensuring the survival of the most useful or pleasing variations"[9]. Within this structure, "conformity to reality, adaptation to power, are no longer the result of a dialectical process between subject and reality but are produced directly by the cogs and levers of industry"[10].

The digital environment creates a situation where "the individual has to invent a self-understanding that optimizes or facilitates their participation in digital milieus and speeds"[11]. This self-understanding develops within systems where "docility and separation are not indirect by-products of a financialized global economy, but are among its primary aims"[12].In this context, "it is no longer a question of imitation, nor duplication, nor even parody. It is a question of substituting the signs of the real for the real"[13]. These systems generate what appears as enhancement: "technical reproduction can put the copy of the original into situations which would be out of reach for the original itself"[14].

Faced with this complexity, users often respond by seeking more technology: "overwhelmed by the pace that technology makes possible, we think about how new, more efficient technologies might help dig us out"[15]. This creates a cycle where "the experience of these shifts inevitably enhances one's attraction to the former, and magnifies the mirage of one's own privileged exemption"[16].The economic forces driving this standardization create "a spontaneously productive and autonomous force"[17] that shapes behavior while claiming to merely reflect it. This force operates within "the formalism of this principle and the entire logic established around it stem from the opacity and entanglement of interests in a society"[18].

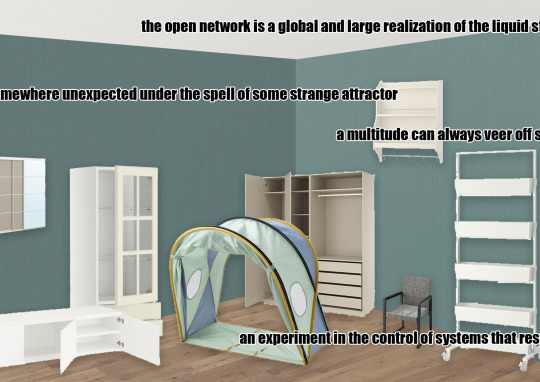

Digital mirrors have transformed into mechanisms where "the open network is a global and large realization of the liquid state that pushes to the limits the capacity of control mechanisms"[19]. While "a multitude can always veer off somewhere unexpected under the spell of some strange attractor"[20], these deviations occur within "an experiment in the control of systems that respond violently and often suicidally to rigid control"[21]. The tools designed to express individuality have become the very mechanisms of conformity, The process remains unfinished, operating in a space where "the problem of fine-tuning the machine is both nonlinear and highly coupled: changing one variable in one direction might produce unexpected results"[22].

References

[1] Terranova, T. (2004) Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age, London: Pluto Press, p.129.

[2] Terranova, T. (2004) Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age, London: Pluto Press, p.126.

[3] Terranova, T. (2004) Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age, London: Pluto Press, p.121.

[4] Crary, J. (2013) Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, London: Verso, p.57.

[5] Turkle, S. (2011) Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other, New York: Basic Books, p.100.

[6] Crary, J. (2013) Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, London: Verso, p.42.

[7] Bridle, J. (2018) New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future, London: Verso.

[8] Bridle, J. (2018) New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future, London: Verso.

[9] Terranova, T. (2004) Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age, London: Pluto Press, p.125.

[10] Horkheimer, M. and Adorno, T. W. (2002) Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments, Stanford: Stanford University Press, p.191.

[11] Crary, J. (2013) Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, London: Verso, p.99.

[12] Crary, J. (2013) Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, London: Verso, p.42.

[13] Baudrillard, J. (1994) Simulacra and Simulation, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, p.3.

[14] Benjamin, W. (1969) The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, New York: Schocken Books, p.4.

[15] Turkle, S. (2011) Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other, New York: Basic Books, p.299.

[16] Crary, J. (2013) Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, London: Verso, p.100.

[17] Terranova, T. (2004) Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age, London: Pluto Press, p.125.

[18] Horkheimer, M. and Adorno, T. W. (2002) Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments, Stanford: Stanford University Press, p.44.

[19] Terranova, T. (2004) Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age, London: Pluto Press, p.125.

[20] Terranova, T. (2004) Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age, London: Pluto Press, p.112.

[21] Terranova, T. (2004) Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age, London: Pluto Press, p.115.

[22] Bridle, J. (2018) New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future, London: Verso.

0 notes

Text

Room 6 : Trapped in a World of Signs

Reality is replaced by signs, where technological enhancement appears progressive but reinforces reliance on imitation and standardization.

0 notes

Text

Room 5 : The Bidirectional Structure of Control

Control exists at both the beginning and end of digital processes, constructing forced conformity through fine-tuned rules and selective variations.

0 notes

Text

Room 4 : The Template Reality of the Marketplace

The marketplace connects through services and products, gradually replacing authentic social realities with standardized templates of existence.

0 notes

Text

Room 3 : Digital Prisons and the Illusion of Customization

Seemingly customizable digital spaces conceal compulsory labor and curated content, trapping users in carefully crafted comfort zones.

0 notes

Text

Room 2 : The Art of Soft Control

Soft control operates with minimal force, balancing specification and creativity, allowing freedom to unfold within hidden boundaries.

0 notes

Text

Room 1 : The Paradox of Personalization

Tools for individuality paradoxically deepen standardization, turning endless possibilities into an illusion of constrained choices.

0 notes

Text

Theoretical text - V&A - IKEA

A Cultural Translation from Theory to Space

0 notes

Text

IKEA wardrobe, 454 pieces

IKEA table, 113 pieces

https://www.ikea.com/gb/en/

0 notes

Text

IKEA shelf, 269 pieces

IKEA desk, 280 pieces

https://www.ikea.com/gb/en/

0 notes

Text

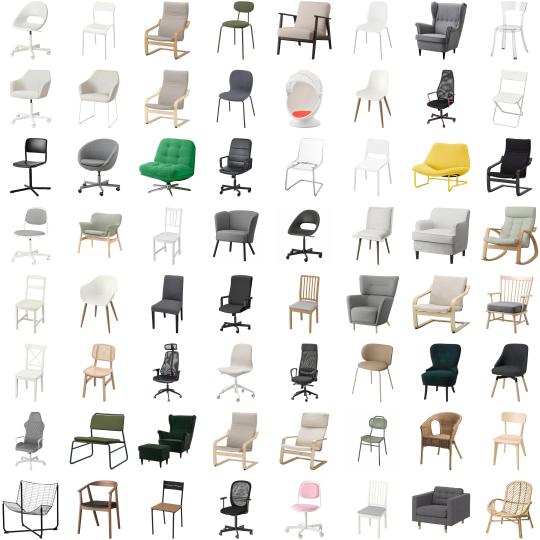

IKEA chair, 286 pieces

IKEA bed, 223 pieces

https://www.ikea.com/gb/en/

0 notes

Text

Art, Design and Performance Museums

Furniture collection (15th century to present), 3935 pieces

Image and description

https://www.vam.ac.uk/

0 notes

Text

Theory, fiction, poetry, prose 40 books

Algorithmic Governance & Surveillance, Platform Capitalism, Digital Power & Control, Virtual Identity

0 notes

Text

Recommendation systems, products, personalization

The personalization of product recommendations is actually an average-based action, which is the opposite of true personalization.

0 notes

Text

Chair as an art and handicrafts

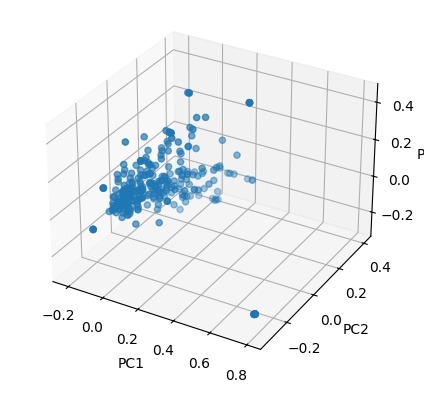

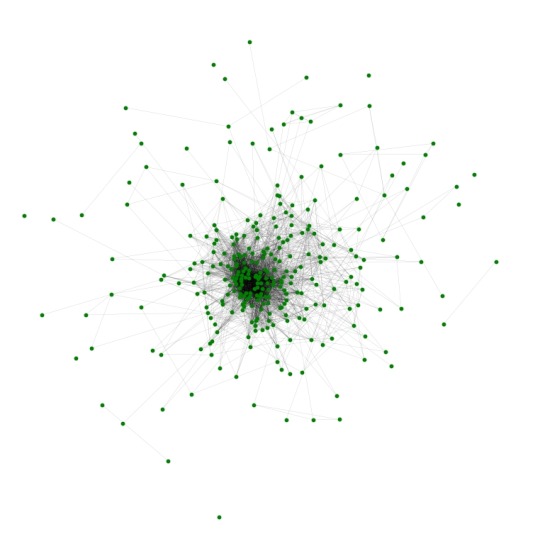

Left: Visualization of word vectors reduced to three dimensions using principal component analysis Right: A visualization of the word vector reduced to two dimensions, with the lines representing two more similar sets of chairs calculated by the cosine algorithm

0 notes

Text

The Average Oracle

In the Cathedral of Data, distance is measured in clicks, and uniqueness is calculated to the sixth decimal place. We are all pilgrims here, wandering through aisles of recommendations, each believing we follow our own path while treading paths worn smooth by millions before us. "Distance is the opposite of closeness," they say, but in this digital sanctuary, everything is simultaneously infinitely far and intimately near.

The priests of this new religion - algorithms - "affect an automated familiarity, gently suggesting offerings they think we'll like." They whisper promises of personalization through the digital confessional, converting our desires into data points, our dreams into demographic patterns. Like ancient oracles, they read the entrails of our browsing histories, finding meaning in the patterns of our clicks and scrolls.

In this temple, "recommendation engines at Amazon and YouTube" serve as modern-day augurs, reading the digital tea leaves of our collective behavior. They "provide relevance" through a paradoxical ritual: the more they know about us, the more they shape us into statistical averages. "To provide relevance, personalization algorithms need data," yet in their hunger for information, they transform individuality into a carefully calculated performance of uniqueness.

Consider the sacred mathematics: "Up to 60 percent of Netflix's rentals come from the personalized guesses it can make about each customer's movie preferences." We are scored, ranked, and sorted, our tastes quantified and our preferences predicted "within about half a star." But what is this precision if not a more elegant form of standardization? Like medieval architects measuring divine proportions, these systems build cathedrals of correlation, where every personal choice becomes a stone in the edifice of average taste.

"The algorithm shouldn't get to decide whether I exist or not," comes the heretical whisper, but existence in this digital liturgy is measured in visibility, in recommendations, in the blessed state of being counted among the countable. We perform our individuality through carefully curated feeds, each click a prayer for recognition, each like a small offering to the gods of relevance.

In the end, "consumers may choose systems that are good at introducing them to new topics," but these discoveries are themselves carefully choreographed, a dance of seeming serendipity performed within the bounds of probabilistic prediction. The "loss of distance in global communications" creates an illusion of infinite choice, while the "physical infrastructure that makes that informational effect possible" quietly constrains our movements to well-worn digital paths.

Like those "brave souls still trying to sell their custom-designed artisan wares" in a marketplace of algorithmic abundance, authentic individuality becomes a rare artifact, a curiosity in a world where "10,257 products range from postcards of crawfish to bumper stickers featuring a piece of cheese" can be generated by feeding "some obscure database of natural images" into the great machine of mass customization.

We have built a perfect system of mirrors, each reflecting not what we are, but what we statistically should be. In this "automated familiarity," we find comfort in being told who we are, even as who we are becomes increasingly indistinguishable from who we are expected to be. The algorithm watches, learns, and in learning, teaches us to become more learnable, more predictable, more average in our uniqueness.

Perhaps true personalization lies not in the precision of prediction, but in the spaces between the data points, in the glitches and gaps where the unexpected still flourishes. For now, we continue our ritual dance of digital individuality, each step measured, each choice logged, each moment of supposed spontaneity carefully calculated to maintain the illusion of freedom within the cathedral of the average.

0 notes