Text

Acute Liver Failure. What Emergency Physicians Should Know.

Acute liver failure (ALF) is a rare entity. There are only about 2,000 cases per year, meaning you will probably see this less than once a year at your emergency department. Recognizing these patients and transferring them to a tertiary liver center is crucial. The liver is the new frontier. The mortality gap between management in a typical community ICU and a specialized liver center is enormous. If you are not at a liver center, and you keep the ALF patient at your hospital, the expected outcome for the patient is death. If you transfer to a liver center, the expected outcome is recovery (with or without transplantation). The contrast is that stark.

Recognizing ALF

There are 4 criteria:

The patient does not have pre-existing cirrhosis

The patient has been symptomatic for less than 26 weeks (half a year)

There is encephalopathy

INR is > 1.5

Grading encephalopathy is not an expectation of the emergency physician, but it is the GCS of hepatologists, and guides management. I recommend attempting this endeavor. My interpretation, hitting the high points for easy memory:

Grade 1: Patients are alert and oriented, but may be a little goofy. Poor concentration and reversal of sleep rhythm are the hallmarks. Obvious asterexis suggests at least grade 2.

Grade 2: Asterexis is obvious. There is some drowsiness and disorientation.

Grade 3: Somnolent, but can arouse to voice. Able to speak, but will give an incoherent history.

Grade 4: Either completely unresponsive, or only arouses to pain.

Note that the INR is the most important liver function test. You can have AST and ALT of one billion; if your INR is normal, you don’t have liver failure. Conversely, AST and ALT can be normal; if your INR is high, you may have liver failure. Always order it when liver disease is suspected.

Fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) is a subcategory of ALF. This is defined by an ALF patient who went from no previous liver disease to hepatic encephalopathy within 8 weeks.

Arrange transfer to a liver center

This is more important than trying to find out the cause. The cause should not change this decision. The vast majority of these patients are young and can live long and healthy lives if their ALF is reversed. Liver centers do more now than just transplantation. Liver failure is arguably more complicated than the failure of any other organ. Liver centers have a multidisciplinary team involving gastroenterologists, neurologists, neurosurgeons, transplant surgeons, and infectious disease. They now have artificial liver technology, liver dialysis, extracorporeal nanorobotic shit teleported from the future…

The bottom line is, if you happen to drink yourself until your eyes turn orange, you’d want to be transferred to a liver center. Do the same for your patient.

What else to do for the really sick ones?

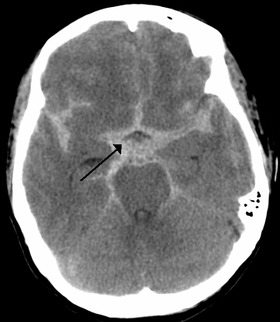

The number one cause of mortality in ALF is cerebral edema. Any ALF patient with grade 3 or 4 encephalopathy should be treated similarly to a severe TBI. These patients should be intubated, head of the bed should be elevated to 30 degrees, and mannitol should be discussed with the accepting doctor. Lactulose should be given per NG tube. A head CT should always be ordered. Advanced cerebral edema can be detected, and ICH often complicates or mimics hepatic encephalopathy.

The number two cause of mortality is infection. If the patient is sick, just give Zosyn. If the antibiotic sleuths from upstairs talk about, “What are you treating?” Just answer, “Yo mama.” If there is significant ascites, diagnostic pericentesis should be performed. If the fluid has an absolute neutrophil count >250, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is diagnosed, regardless of symptoms. With ultrasound guidance, this procedure can be safely performed in 5 minutes.

The number three cause of mortality is bleeding. If there is any scary bleeding, you must correct coagulopathy:

Give PRBC in the same manner as you would in a patient without ALF.

Start with 4 units of FFP. 1 or 2 units will not be enough.

Give platelets if the platelet count is <50,000

Give cryoprecipitate if the fibrinogen is <80. Oh yeah, order a fibrinogen level.

If there is variceal bleeding, you need to stop it and stabilize the patient before transfer. You may need to involve your local GI guy and intensivist. Two special drugs: octreotide and Zosyn. The official guidelines say something like ceftriaxone, but the sepsis gestapo is out and retrospectively reviewing your chart; and these patients almost always will meet SIRS and end organ injury.

ALF patients are often hypotensive. They may have significant peripheral edema, but they are intravascularly depleted. Bolus fluids up to 30mL/kg. Also add albumin. Hepatic failure and hypotension is the only scenario I give albumin. I give 25g of 25% solution. If MAP is still less than <65, I use the lactic acid. If it is normal, I do not start vasopressors unless the accepting doctor demands it. Many liver patients are baseline hypotensive and forcing a normal blood pressure with vasopressors may be detrimental.

Keep the patient NPO and check the glucose every 1-2 hours. These patients get hypoglycemia hard. They may die from hypoglycemia. These patients will require much more glucose to reverse hypoglycemia, and they will take longer to clinically recover from hypoglycemia.

Give N-acetylcysteine (NAC) for Tylenol poisoning and Amanita mushroom poisoning. For Tylenol poisoning, Tylenol levels are useless by the time ALF develops, and are usually 0. NAC is still hepful. For amanita mushroom poisoning (which mainly occurs in California, Oregon, Washington), add IV penicillin G and PO/NGT silibinin or activated charcoal.

Do not give benzodiazepines unless behavior is completely unmanageable. Benzoes are cleared by the liver, and will make the patient’s exam unreliable for a very long time. If fact, if the patient develops seizures, phenytoin and not a benzo is the first line. If the patient is intubated, propofol is good for agitation. If a benzo must be given, I recommend small aliquots of Versed.

Take home points

Identify ALF: No known cirrhosis, symptomatic for <0.5 years, INR >1.5, hepatic encephalopathy

Aim to transfer all patients with ALF to a liver center

Always get a head CT

Sick or not sick? Give Zosyn to everyone who is sick

Severely depressed LOC? Intubate and assume elevated ICP.

Bleeding? 4 units of FFP.

Hypotensive? 25g of 25% albumin and fluid boluses up to 30mL/kg

Check the glucose often. Treat hypoglycemia aggressively.

Don’t give benzodiazepines

1 note

·

View note

Text

Running Code Blues Better than ACLS

There is the phrase often taught to medical students, “The patient is already dead. You cannot hurt a dead person.” This is a wise adage when beginning medical training, because it permits aggressive therapies in desperate situations. But, I have two problems with the expression:

The patient is already dead.

No. He or she is not dead until I make the pronouncement. I stopped using the term dead. The correct term in the undifferentiated code blue patient is “No outward signs of life.”

You cannot hurt a dead person.

You can hurt a salvageable patient with no outward signs of life by taking the wrong approach. A classic example would be to shock a patient in PEA. The bigger idea, however, is that by trying to resuscitate an unsalvageable patient, you are hurting other patients. As an ED attending, I am responsible for the waiting room. I am responsible when I steal two nurses, two techs, a respiratory therapist, and a pharmacist to help with my code blue.

The start of a code blue is critical. You must rise above ACLS. A competent team of ED nurses can run ACLS perfectly without a physician. ACLS takes you from zero chance of survival to a poor chance of survival. Do not be satisfied with just knowing ACLS.

General tips for running the code blue:

Diagnostic parsing is the focus. As the doctor and the team leader, you must treat a diagnosis, no matter how presumptive. PEA is not a diagnosis - it is an exam finding. Share thoughts and information out loud to define the patient’s pathophysiology in a treatment-oriented category.

If you have the personnel available, I recommend against touching the patient. My residency taught me to run the code with my fingers on the femoral pulse, which I’ve found to be worse than useless.

Pulse check should be done at the carotid pulse, and only every two minutes. The femoral pulse is harder to palpate and the leg is less important than the brain.

Determine the quality of chest compressions, by observing the quality of chest compressions. Always swap out after two minutes, or if the current compressor just doesn’t get it. The femoral pulse can be absent in a patient with severe atherosclerosis or calcified arteries. I’ve had a case where identification of ROSC was delayed because she had severe atherosclerosis, and regained pedal pulses before her femoral pulse.

On arrival, if the patient has a shockable rhythm, defibrillation as soon as possible is the immediate goal. If the patient has asystole or PEA, the mnemonic should be NQU: Narcan, QRS, Ultrasound.

If the patient is intubated by EMS, confirm placement as soon as possible. If the patient is not intubated, but has no issues with BVM or supraglottic device, I do not intubate the patient unless there is cyanosis or concern for respiratory arrest. You can and should attach capnography to whatever is being used.

How good is the resuscitation going? Again, you do not need your hand on the groin. This will distract you from what is really important:

Bedside ultrasound during pulse checks. No cardiac activity can be used to identify an unsalvageable patient.

End-tidal CO2. An ETCO2 persistently less than 10 can be used to identify an unsalvageable patient.

A shockable rhythm indicates hope

In a non-shockable rhythm, a fast HR indicates hope

Specific tips for specific scenarios:

Witnessed arrest with a shockable rhythm

Anywhere between 60-90% of the time, this is due to acute myocardial infarction. Activate the cath lab as soon as you can confirm the arrest was witnessed and the rhythm was shockable. The interventionist may refuse a pulseless patient, but he or she needs to be ready when you do get pulses back.

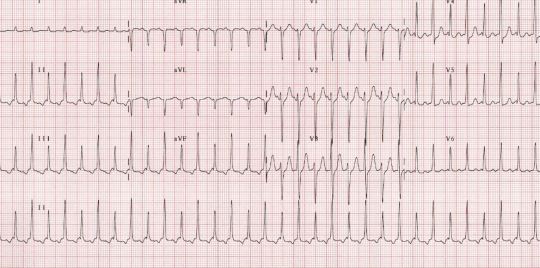

The post-ROSC EKG is not nearly as predictive as an EKG in someone who has not had cardiac arrest. Do not call off the cath lab if it does not show a STEMI. On the flip side, do not inappropriately call a STEMI based on the EKG in a patient who arrested but did not have a shockable rhythm.

Space out the epinephrine to every 5 minutes. Epinephrine can cause ventricular dysrhythmias, so it may not be as helpful in a patient you are trying to get out of a ventricular dysrhythmia.

Amiodarone works. I don’t care about Amal Mattu and his literature. I bolus and drip everyone presenting with a shockable rhythm.

Unwitnessed arrest with a non-shockable narrow complex rhythm

These patients overall have an abysmal prognosis. The most important use of the ultrasound is to identify cardiac standstill.

I immediately ultrasound these patients. No cardiac activity equals death. I stop the code right then and there.

Arrest with a non-shockable wide complex rhythm

Two things: hyperkalemia and acidosis.

Give calcium. Gluconate or chloride? Whatever calcium is grabbed out of the code cart first is the better calcium.

Give at least 4 amps of bicarbonate. Realize that 1 amp does nothing.

Give IVF wide open. The solution to pollution is dilution.

Hyperventilate. Give a breath every 2-3 seconds.

PEA with cardiac activity with a pericardial effusion on ultrasound: give IVF wide open and perform pericardiocentesis.

PEA with cardiac activity with the right heart larger than the left heart on ultrasound

Give TPA for presumed massive pulmonary embolism. If the patient is full code, there are no contraindications for TPA in the setting of cardiac arrest from suspected massive PE. I have given it to patients with known history of ICH and nobody has yelled at me.

Consider emergent thrombectomy if available

PEA with an underfilled or hyperdynamic left ventricle

Give IVF wide open.

Ultrasound the abdomen. If there an AAA or free fluid that is not obviously ascites, it is reasonable to call for uncrossmatched blood.

Remember that an AAA and a negative FAST means the rupture is likely retroperitoneal.

In a young female with free fluid, consult OB/GYN.

Resuscitation should be done through at least two lines: either large-bore peripheral IV, trauma central line, or IO. I recommend two IOs in these patients because you can always use more lines, and these are the fastest to obtain. You can give blood products and any drug your heart desires through the IO.

Once you get ROSC, I believe norepinephrine is the best drip to start in these cases. Unless obvious bleeding is identified, it is wise to assume an infectious component and start Zosyn and vancomycin.

PEA with an overfilled left ventricle with severely reduced LVEF

This is the patient you want to give epinephrine to every 2 minutes. Still give IVF, but don’t give more than a liter.

Consult with the cath lab for placement of an intra-aortic balloon pump

I don’t mess with dopamine because it is arrythmogenic and if a patient with end-stage CHF goes into a ventricular dysrhythmia, it’s likely game over.

I don’t mess with dobutamine because it reduces systemic vascular resistance (SVR)

Once you get ROSC, I believe epinephrine is the best drip to start in these cases.

I can’t find the heart!

Special case I will mention from residency. I was assigned to do ultrasound. A patient came in with PEA and another resident intubated. The attending thought the tube went into the right mainstem due to lack of breath sounds on the left. The tube was re-adjusted, but nobody auscultated the lungs again. I could not find the heart with ultrasound during the pulse checks, and felt like a useless idiot. The patient was bagged for about 10 minutes before a CXR was ordered to check the position of the ET tube.

The diagnosis was left tension pneumothorax, and both lungs and the heart were in the right hemithorax. A chest tube was immediately placed, but the patient died. She was 18 and found with a crack pipe in her car. Presumably, inhaling the crack caused the pneumothorax. The lesson here is to not miss tension pneumothorax as a cause for the cardiac arrest. The diagnosis should have been considered when auscultating breath sounds, which you should still do on all cardiac arrests. The diagnosis can be confirmed by pleural ultrasound using the linear probe.

Take home points

Every PEA/asystole should get Narcan.

For a wide-complex non-shockable rhythm: calcium and at least 4 amps of bicarb

After the above, if there is no cardiac activity on US, the patient is dead. Don’t use up resources on a patient that is not salvageable. Rare exception for obvious environmental hypothermia.

If the arrest is witnessed, and the initial rhythm was shockable, activate the cath lab.

For a shockable rhythm: give amiodarone early and space out the epinephrine – they don’t need the extra myocardial irritation.

Arrest from cardiogenic shock: epinephrine every 2 minutes and start epinephrine drip after ROSC. Try to get interventionist to put an intra-aortic balloon pump.

Arrest from distributive or hypovolemic shock: Lots of IVF. FAST exam for hemoperitoneum or AAA. Norepinephrine is the best drip after ROSC.

Bedside ultrasound can quickly identify the big three reversible causes of obstructive shock: cardiac tamponade, massive PE, and tension pneumothorax.

#emergency medicine#acls#cardiac arrest#pea#asystole#ventricular fibrillation#ventricular tachycardia#ultrasound#code blue

0 notes

Text

Bacteremia causing low back pain

I had an interesting case… if for no other reason than I tried very hard to discharge a patient developing septic shock - and only due to intractable pain did I admit her to the observation unit. But, I now have an n of 2 for low-grade fever and non-localizable severe low back pain from bacteremia and no other good explanation.

Real Case #1

Healthy 51 male presented for 3 weeks of intermittent fevers, fatigue, night sweats, and generalized aches. On a routine visit to his ophthalmologist, he was diagnosed with possible endocarditis by fundoscopy. He was referred to get an outpatient echocardiogram, which showed mitral valve vegetation, and he was referred to the emergency department.

The patient did not look bad. He had no health issues or risk factors that would predispose him to endocarditis. His most bothersome symptom was severe low back pain that could not be reproduced with palpation. He had a temp of 100.9 and a pulse in the 110s. There was nothing else on exam.

Obviously, it was a no-brainer case for me. The rockstar was the ophthalmologist. The patient had 3 sets of blood cultures and antibiotics started in the ED. He was admitted. They determined he did not need surgery during his stay, and he had a PICC line inserted, and he was discharged after an unremarkable hospitalization. The final blood culture result was Streptococcus mutans. Presumably, the source was dental, but the patient did not have a recent dental procedure.

This is why I don’t floss.

Real Case #2

Healthy 60 year old female presented for fever, nausea, vomiting, and low back pain with acute onset 12 hours ago. Her initial vitals: 100.2F, P 107, RR 20, BP 113/75, and 96% on RA. She was trying not to move because any movement caused significant low back pain in a belt like distribution, wrapping around to the bilateral lower flank. She had no localizing signs on physical exam. There was no tenderness of the abdomen, CVA, flank, or back. There were no urinary symptoms or neurological signs or symptoms.

A sepsis workup was ordered. Initial labs showed a WBC of 13.4 with no bands, and lactic acid of 2.1. She was given IV Dilaudid and 1L NS. CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast and CXR were negative. UA was weakly positive with 10 WBC and +1 leukocyte esterase. Due to absence of urinary symptoms, I did not call this UTI. Repeat lactic acid after 1L NS was 1.4. She was still having severe low back pain, but still had no tenderness anywhere. She was given some Norco and Valium.

I decided to discharge her with a diagnosis of viral syndrome. I charted against sepsis and the need for antibiotics. Her final set of ED vitals were: 98.8F, P 92, 123/64, R 16, and 96% on RA. She was comfortable while at rest. Husband was uncomfortable with discharge because she was groggy. I told him that it was due to the pain meds, and she will be better after a good night’s rest. I pushed through with discharge. Husband came back to tell me she was in too much pain to put on her own clothes. That’s when I decided to admit her to observation for pain control. I remember both the nurse and I being disappointed by this patient’s wussiness.

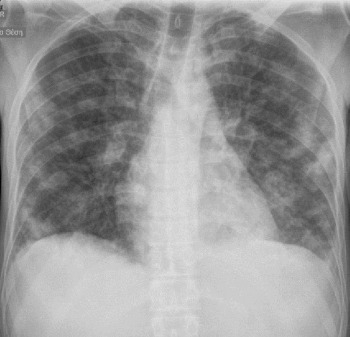

Within 2 hours in observation, she became hypotensive and both of her blood cultures grew GPC in chains. Repeat CBC showed WBC 11.9 and 22% bands. Repeat lactic acid was 1.8. She was started on Zosyn and Vancomycin and admitted to the hospitalist. She developed hypotension refractory to fluids, and was admitted to the ICU. She received a central line, but became normotensive after and did not need vasopressors. She developed noncardiogenic pulmonary edema and hypoxic respiratory failure, requiring high-flow humidified O2, but did not need intubation. She received thoracic and lumbar spine MRI, and these were negative. Urine cultures were negative. After 2 days in the unit, she was stabilized and returned to the floor.

She developed septic arthritis in the left knee and right ankle. Arthrocentesis showed >100,000 WBC with 86% segmented neutrophils. Gram stain and culture were negative. Orthopedic surgery washed her out. She had a PICC line inserted and was discharged in good condition on IV antibiotics. The final blood culture result was group A Streptococcus pyogenes. Source of bacteremia was guesswork. If I was able to discharge her, she may have bounced back with a fulminant toxic shock syndrome.

Discussion

Reviewing for the boards taught me that acute hemolytic reaction to blood transfusion causes severe low back pain. This is not very relevant because I will probably never see an acute hemolytic reaction in my career. But, this got me thinking if severe low back pain that is non-localized and non-reproducible to palpation can be generalized to bad inflammatory juju in the blood, such as bacteremia? Not a lot has been published about this, but I will pause next time I want to discharge a bad back pain and low-grade fever that I want to chalk up to viral syndrome.

0 notes

Text

The EH Score... Because the HEART Score Is Rubbish

The HEART score should not be used to trump your own clinical decision making. It is not better than the gestalt of an emergency physician. I only document a HEART score if I discharge a chest pain patient and the HEART score happens to be 3 or less. I still discharge patients with HEART score >3. I just don’t document the HEART score. I also do not let heart score of 3 or less prevent me from pushing for an admission on a patient I am concerned about.

The HEART score does not factor into my clinical decision making. I check it as an afterthought to see if I can add beef to my documentation. I have a simpler score. It’s perfect since I am Canadian. But first, I’m going to criticize the components of this HEART score that has gained so much popularity in EM.

Why HEART is rubbish, letter by letter.

History: Why do you need to proceed if you think the history is “highly suspicious?” By this scoring system, you only get 2 points for a highly suspicious history, meaning you have a point to spare to still be considered low risk by HEART. This is ridiculous, and implies this scoring system is intended for complete novices in evaluating the chest pain patient. If you are giving 2 points for H, you are done – the patient is being admitted.

EKG: You get 2 points for “significant ST-depression.” Once again, this implies this scoring system is intended for complete novices. I will explain in detail later on, but not all ST depressions are created equal, and the dreaded horizontal (or planar) ST depression is a Do-Not-Pass-GO finding. In fact, people with this type of ST depression and ST elevations (i.e. STEMI) do better than people with this type of ST depression alone (i.e. NSTE-ACS with ischemic EKG). Meanwhile there are other ST depressions that are fairly benign.

Age: You get 2 points for being >65. I am less worried about missing an atypical presentation of ACS in someone >65 than someone <45 (0 points according to HEART). The patient who is 35-45 with chest pain, with a family that is still very much dependent on the patient being alive and well is much higher risk than the nursing home patient. The cases that end up in books like Bouncebacks are younger because they wind up being the ones with the multi-million dollar lawsuit.

Risk factors: The set list of risk factors includes sedentary lifestyle, smoking, HTN, HLP, smoking, and family history of early CAD. It really misses some of the riskier risk factors such as CKD, lupus, and antiphospholipid syndrome.

Troponin: It takes balls to discharge someone with chest pain and an elevated troponin. Balls you should not have or even be curious about acquiring.

The EH score!

There are two binary decisions. Is the EKG bad? Is the History bad? E and H. 0 or 1. If the score is 2, you start heparin, and you call intervention to try to get a cath as soon as possible. If the score is 1, you admit the patient, and call the cardiologist for recs and see if he/she wants anything started in the ED. If the score is 0, you call the cardiologist to see if expedited outpatient follow-up can be arranged.

EKG is the most important part of my chest pain evaluation. I like to see it before the patient. After I decide there is no concern for STEMI, I look for ST depressions.

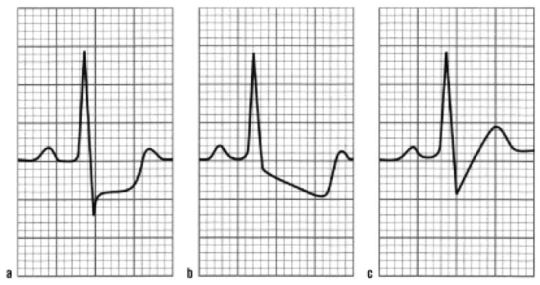

A is ischemia. It is more specific for ischemia than ST elevations. If these depressions are in leads V1-3, posterior leads must be obtained to evaluate for posterior wall STEMI. Otherwise, this would get you 1 point for E.

B is ischemia vs LVH. It really depends on the T wave. If the ST downslopes into an inverted T wave in the lateral leads, this is LVH, which is not concerning, especially if it is present on an old EKG. This gets you 0 for E. If the ST downslopes into an upright T wave, this is concerning for ischemia, especially if it is not present on an old EKG. This gets you 1 point for E.

C is unlikely to be ischemia. An upsloping ST depression gets you 0 points for E.

History is the other crucial decision factor. There are two reasons the history is concerning to me:

Exertional angina or anginal equivalent. This means the symptom started with exertion, and improved with rest. This is more important than what the actual symptom was. Heartburn, belching, pressure, tightness, shortness of breath, diaphoresis, vomiting, severe fatigue, I-just-didn’t-feel-right… it doesn’t matter. If usual exertion produced unusual symptoms, that is very worrisome.

Active chest pain that looks like heart attack. If you walk into a room and the first thing you think is “heart attack,” you are done. Don’t let a HEART score make you reconsider.

Putting it together

E + H = 2: This is NSTE-ACS. If the troponin is positive, this is now NSTEMI. In either case, start heparin and push for immediate cath, or at least urgent cath. The RITA 3 trial supports routine cath for these cases for short-term mortality benefit. The survival gain at 5 years is gone at 10 years on follow-up. Pundits are arguing. I don’t care. 10 year survival isn’t in my EM mindset.

E + H = 1: Admit the patient and consult cardiology for further recommendations. Active chest pain should get heparin and a cath, in my opinion. But I am willing to follow cardiologist recommendations.

E + H = 0: Call cardiology for recommendations and come up with a mutual decision between you, the cardiologist, and the patient. I love shared decision making. There is very little benefit in observation admissions for low risk patients in my opinion, so I am biased towards discharge. If the patient is reliable to follow up and a cardiologist is available and on board with the plan, discharge is appropriate. Whenever available, a cardiologist should be involved in all cases of chest pain where ACS is a possibility. I’m sorry to PCPs, but they are the reason why HEART scores were created.

If there is no reliable follow-up, I lean towards punting the risk upstairs.

0 notes

Text

How to Use Lactic Acid in the ED

Lactic acid is the most important clinical indicator of shock. Only order lactic acid if you are concerned your patient is at risk for shock and death. This is especially true with the new nutty CMS sepsis core measure. FUCK THAT SHIET. If you are going to order a lactic acid, a second lactic acid within 3 hours should be automatically ordered. I often get a second lactic in the 1-2 hour window just to one up the code sepsis protocol. It is the SECOND lactic acid that is the most important prognostic indicator for your patient.

The first lactic acid is greater than 4. What does it mean?

Get a second lactic.

Lactic acid greater than 4 with a clinical suspicion of shock means your patient really is in shock. On the flip side, a lactic acid less than 2 means your patient, at the time of the blood draw, is not in shock. Shock is best defined as global tissue hypoperfusion. When there is no perfusion to a tissue, it switches to anaerobic metabolism, generating lactic acid. This physiology is universal for all human beings. A normal lactic acid rules out shock. It does NOT rule out about-to-go-into-shock in a deteriorating patient.

While a normal lactic acid rules out shock, a very high lactic acid does not equal shock. There are multiple non-shock states that produce high lactic acid. The most common ones I come across in the ED are environmental hypothermia, seizure, and cancer. Note that simple dehydration producing a high lactate IS shock. You can bill for shock, put in critical care time, and reap the RVUs. This is just an easily reversible form of shock.

In all cases, when you start with a lactic acid greater than 4, and your next lactic acid is increasing, this is bad. It means your patient is dying. On the flip side, if the lactic acid is greater than 4, and the lactic acid is improving with therapy, I have no problem pushing for a floor admission, even if the original diagnosis is septic shock (as long as there is no vasopressor requirement to maintain MAP).

The first lactic acid is less than 2. What does it mean?

Get a second lactic.

As mentioned above, a lactic acid less than 2 rules out shock; but it does not rule out impending shock. I want to specifically bring up the case for acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI). It is a common misconception that a normal lactic acid rules out this diagnosis. An elevated lactic acid is the first LATE sign of AMI. It means necrosis, peritonitis, and shock are already developing. If you are concerned enough to get the initial lactic acid, you are automatically concerned enough to get a second lactic acid.

Real case #1: Elderly female with a-fib presented with sudden onset of abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea. CT with IV contrast showed bowel wall edema and a closed loop bowel obstruction. There was no specific mention of ischemia in the report. Her initial lactic acid was 1.3. After a bitchfest with the surgeon, she was admitted to medicine for conservative management. She promptly became hypotensive on the floor. Lactic acid was repeated, and it was 1.9. She was taken for ex-lap, and she was found to have ischemic bowel. The patient died shortly after the OR.

Real case #2: Elderly female on chemotherapy presented with fever and no other symptoms. She was stable and well appearing. Her initial lactic acid was 1.8 and her vital signs were normal except for temp of 101. BP was “soft” at 100/60 range. Her ANC came back essentially 0. After 2L of IVF and neutropenic fever abx coverage, her BP did not change and she became tachycardic in the 110s. Second lactic acid was 8.0. She was still well appearing at this time. She was admitted to the ICU, where she developed fulminant septic shock and died.

Take homes: Lactic acid is often more telling than the clinical appearance of the patient. An increasing lactic acid despite optimal therapy portends badness. It does not matter if it goes from 1.3 to 1.9. Note that if the second lactic acid in case #1 came back 1.3 or less, that would make AMI very unlikely. But the fact the initial lactic acid was <2 should not be used to argue against the possibility of AMI. The fact that the lactic acid increased with therapy, despite still being <2, suggested AMI.

The first lactic acid is between 2 and 4. What does it mean?

Get a second lactic.

It is high risk to discharge someone with lactic acid >2. With the new CMS sepsis core measure, I no longer believe severe sepsis exists as it is defined. However, lawyers can easily twist things to show that you discharged someone with severe sepsis, if there is any bad outcome. Many, many well patients will have a lactic acid in the 2-3 range. This is why you should not get the first lactic acid if you are not concerned; you may be shooting yourself in the foot.

If you order the first lactic acid for the right reasons, and it returns between 2 and 4, and then you resuscitate the patient, repeat the lactic acid, and it is still >2, this patient should be admitted. If the lactic acid is increasing, I recommend involving some specialist or intensivist.

Bottom line: get a second lactic. It is the most important prognostic test in the critical patient.

0 notes

Text

10 Pain Management Myths that Will Screw You

Myth 1: There are reliable objective findings of pain

Severe pain does not reliably cause abnormal vital signs. The absence of tachycardia, hypertension, etc. does not mean a patient is not in severe pain

Myth 2: Patients requiring multiple doses of opiates are drug seekers

Be very careful. One of two things are happening:

The patient has tolerance to opiates, requiring larger doses to achieve therapeutic effect

The patient has badness. Unexplained pain out of proportion (POOP) = ischemia until proven otherwise. Examples: scrotal POOP is torsion; chest POOP is ACS; abdominal POOP is mesenteric ischemia; soft tissue POOP is necrotizing fasciitis; extremity POOP is acute limb ischemia… get the picture? As an aside: what is the only organ too dumb to communicate in the language of pain when it loses its oxygen supply? The brain (except the cerebellum).

Pro tip: for people on chronic home opiates, get their home dose, and use a conversion table to give them at least the equivalency dose in the ED

Myth 3: The reason for drug-seeking behavior is drug addicts wanting to get high

The reason for drug-seeking behavior almost every time is pain avoidance. The patient is seeking the drugs for legitimate pain.

The vicious cycle goes like this: the patient dramatizes the pain. If you label the patient as an addict, and deny pain relief, the patient will believe there needs to be a more compelling dramatization the next time in order to get pain relief.

Myth 4: Malingerers come to the emergency department to get high

True malingerers are far and few in between. They are after the opiate prescription.

Corollary: ask all patients who have a pain complaint if they would like pain medications to make their ED experience more comfortable, and give them pain medications!

Myth 5: I should wait for a full physical exam or diagnostic testing before giving pain medications

Do not wait. A distressed patient who cannot give a detailed history or cooperate for a full exam needs pain medications IMMEDIATELY. It can only increase diagnostic accuracy.

If you really, really, REALLY feel righteous enough to play the “I don’t believe my patient” game, don’t order any tests! It bothers me when a provider needs to wait to see if a test shows “true pathology” before willing to give pain meds.

Myth 6: Opiate prescriptions are harmless

As much as I advocate liberal use of opiates in the ED, I admonish against liberal prescriptions for opiates

The majority of opiate addiction is started with a legitimate prescription

Opiate prescriptions, if necessary, should only be enough to last 3 days – enough time to arrange for outpatient follow up

You should include “No driving” directions explicitly in the discharge instructions. Even though the pharmacist and/or drug pamphlet will give the same warning, you can be liable if a patient drives under the influence of your prescription, and causes or receives harm.

Myth 7: Tramadol is not an opiate

Tramadol (Ultram) is an opiate. It has inferior analgesic properties. It has serotonergic properties. It can cause serotonin syndrome and seizures in overdose. You can get high from it, and it is habit-forming. It can still be diverted. I hate this drug.

Myth 8: Ketorolac is the best NSAID

It is not superior to oral ibuprofen. No NSAID is superior to good old ibuprofen in terms of analgesia. Ketorolac is useful in that it is a widely available injectable NSAID for when PO meds are contraindicated.

Oral ketorolac should not exist, but it does. Ketorolac has about as many black box warnings as Michael Phelps has gold medals. It has warnings for cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, pregnancy-related, and renal side effects. This medication cannot be prescribed for more than a 5 day course. Better yet, don’t prescribe it altogether.

Myth 9: Fentanyl does not drop the blood pressure

The myth goes like this: morphine has direct histamine-releasing properties, which causes vasodilation and lowers BP by that mechanism. Fentanyl has no such property. It has such a negligible effect on the heart or vascular tone that it is preferred for open heart surgery.

Open heart surgery does NOT apply to the ED. In the ED, pain and suffering are ubiquitous. Pain is the best vasopressor. When you remove pain, regardless of the agent, you will lower the BP.

Corollary: the one scenario I may delay giving pain relief to a patient in severe pain, is a crashing trauma patient in hemorrhagic shock.

Myth 10: I should use the words “narcotic” and “addict” when trying to withhold opiates from my patients

Don’t shoot yourself in the foot. Understand your patient population.

“Narcotic” is a police term to describe certain substances sharing one thing in common: illegality. It has no medical meaning. I have never in my life given any patient a narcotic. I give opiates. Narcotic is a very inflammatory word to many patients. Don’t use it.

“Addict” is not as bad, but of course it carries a very negative connotation. I prefer the term “habit” instead of “addiction,” and “habit-forming” instead of “addicting.” Once a patient volunteers that he or she is an addict, you can then use the word at will.

The Principles

Do not delay in treating acute pain in the emergency department. Do not withhold the necessary doses of opiates to lower pain to a tolerable level. The number one cause of “drug-seeking” is actually pain relief/avoidance.

Patients needing multiple doses of opiates in the ED should increase your suspicion for badness; not your suspicion for malingering

Be very careful about prescribing opiates: this is how addictions start; this causes MVCs; this is what malingerers are after (not that one time dose of Dilaudid).

0 notes

Text

Rapid Sequence Intubation

The overlooked indication: anticipated clinical course.

Example: 35 year old female presents with suspected epiglottitis. There is voice hoarseness and anxiety, but there is no respiratory distress, stridor, or drooling.

If this patient can be transported immediately to a monitored setting in the same hospital with ENT support immediately available if there is deterioration, intubation can be delayed. If this patient is in the small community ED setting that requires a 60 minute transport, she should be intubated.

The only airway assessment that will likely be tested is the Mallampati score. The higher the score, the more likely the airway is to be difficult.

Apneic oxygenation is now commonly employed and should, arguably, be standard of care

After BVM for pre-oxygenation and before intubation attempt, a normal nasal cannula is applied with maximum flow (usually 15L) to allow passive oxygenation during period of apnea

This has been show to increase time to hypoxia

Pretreatment medications

Nothing has been shown to definitely improve outcomes. You must give the medication and wait 3 minutes in order to get the theoretic benefit. This definitely delays intubation. Keep that in mind before you feel the need to get fancy.

Elevated ICP: lidocaine 1.5 mg/kg + fentanyl 3 mcg/kg

Cardiovascular disease: fentanyl 3 mcg/kg

Reactive airway disease: lidocaine 1.5 mg/kg + albuterol 2.5 mg nebulized

Positioning

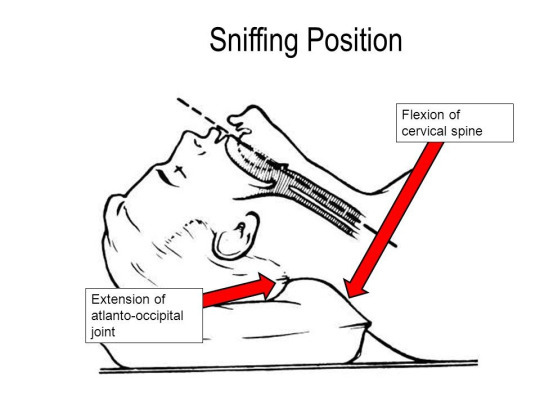

The optimal position is the sniffing position, which is to say the head is extended, and the lower C-spine is flexed

This obviously should not be attempted in there is concern for C-spine instability

Induction medications

Propofol is ideal for hypertensive patients with neurological emergencies (such as SAH or status)

Cons: Lowers the blood pressure. Do not use in hypotension, trauma, and other potential cases of hypovolemic shock

Pros: Can help stop seizures and emesis

Etomidate is a good default induction agent

Myoclonus is an expected side effect. May lower seizure threshold

Adrenal insufficiency with a one-time induction dose has not been shown to be clinically relevant. You ARE allowed to use in septic shock

Pro tip: They say etomidate has no cardiovascular effect, but this WILL drop the pressure in a trauma patient with hemorrhagic shock, especially if they are not receiving a bolus of fluids or blood. Be careful

Ketamine is the best agent for trauma and other causes of potential hypovolemic shock

You ARE allowed to use in head trauma. In fact, ketamine is neuroprotective and may be ideal for these patients

Absolute contraindications: age <3 months and known schizophrenia. These are outdated, in my opinion, but still are part of ACEP guidelines

The real contraindication is severe or acute cardiovascular disease. Ketamine is sympathomimetic, and will raise BP and HR. You do NOT want to give to your cardiogenic shock, hypertensive emergency, ACS, or aortic dissection patient

Emergence reaction is the most common side effect. Laryngospasm is rare, but is the most serious side effect

Ketamine has analgesic properties. Propofol and etomidate do not.

Some combination of opiate, benzodiazepine, and/or barbiturate is old school, and is going to be a wrong choice for induction because of strong and long-lasting effect of lowering BP

Paralytics

Succinylcholine is short-acting.

Sux lasts 5-10 minutes, which is good, because patients become quickly examinable after intubation, and can let you know if your post-intubation analgesia/sedation sucks donkey ass. This is the biggest reason why sux is my default paralytic

You cannot give sux if you suspect hyperkalemia, or if there is the potential for neuromuscular junction dysfunction that has been present for 5 days (think GBS, myasthenia gravis, muscular dystrophy, severe burns or crush injuries that are 5 days old or more, etc.)

More sux is better than less sux. Painful effects of muscle fasciculations can be lessened by giving 1.5 mg/kg (or more) of sux rather than the pansy 1 mg/kg.

Rocuruonium is long-acting.

Roc lasts 30-60 minutes, which is bad. Patients cannot tell you they are aware or in pain, and ED physicians are notorious for ignoring patients even when they are telling you they are in pain. This is a huge disadvantage for roc, in my opinion

Roc is a safe medication to give in all circumstances. You don’t have to worry about hyperkalemia. That is why some advocate using roc on everyone. You’d better be on-the-ball with your post-intubation management, if you take this approach.

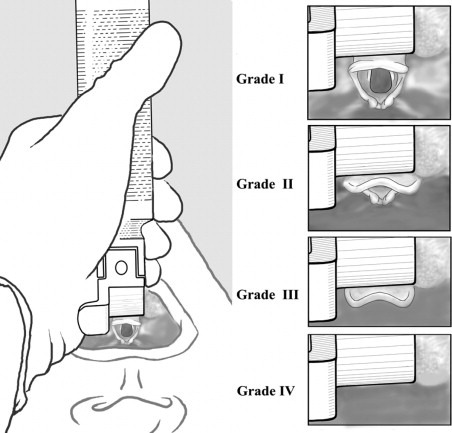

Comack-Lehane laryngoscope view is the moment of truth for DL

The Mallampati has poor correlation with the actual laryngoscope view you will end up getting. The views you get with direct laryngoscopy are graded I to IV, with I being the easiest, and IV being the most difficult, just like Mallampati

Tip for residents: do not break out the anatomy book when an attending asks “what do you see?” when you are intubating and already sweating bullets. Just shout out the grade.

Comack-Lehane Grades III-IV are predictive for difficult intubation. This is when you get bougie or switch to video laryngoscopy.

Cricoid pressure does not prevent aspiration during RSI. That point is settled. Cricoid maneuvers, such as the BURP, may be worthwhile to get you a better Comack-Lehane grade

Gum-elastic bougie serves two purposes

It can hook under the epiglottis and reach that anterior cord that cannot be reached with just the ETT.

It can immediately tell you if you are in the esophagus. If you do not feel palpable clicks when passing the bougie, and the bougie can keep advancing without hitting an obstruction, you are in the esophagus.

Video laryngoscopy

Right now, December 2016, there is no clear winner in the DL vs VL for uncomplicated intubations debate. I still prefer DL first; if for no other reason than to not let everyone in the room see how poor my hand-eye coordination is

Situations of limited mobility are reasons to forgo DL, and go straight to VL

C-spine immobilization required

Limited mouth opening

Morbid obesity

Situations of massive secretions are reasons to forgo VL

Pro tip: if the secretions are esophageal (e.g. massive hematemesis), and you cannot see anything with DL, blindly insert the ETT. This will likely end up in the esophagus, but may redirect the secretions into the tube to allow for VL

Proof of placement

The gold standard is waveform capnography. On exams, “direct visualization of passage” is a just-as-good answer. This is bullshit in practice; “visualization” is a qualitative and relative term due to the unpredictability of weird anatomy, secretions, etc.

Auscultation can be done to increase suspicion for esophageal intubation, or right mainstem intubation; it cannot prove correct positioning.

The CXR is done to visualize the position of the ETT with respect to the carina. It cannot reliably tell if the ETT is in the trachea, or the esophagus.

No high-fives after the tube is in place. The next part is where we tend to fuck up.

Post-intubation analgesia and sedation continues to be a widespread fail among our specialty. This fact may be tested. Exactly how to provide post-intubation analgesia and sedation is varied and situational, so it is unlikely to be tested.

Wasn’t that more fun and high yield than going through the 8 P’s? In case you disagree…

Preparation

maybe know the Mallampati.

everything else is intuitive. Go to video laryngoscopy if there are mobility or mouth opening issues

Pre-oxygenation

apneic oxygenation every time

Pretreatment is low-yield academic nonsense

Paralysis and induction

succinylcholine, except when hyperkalemic or NMJ disorder

propofol if you want the BP lowered, or to stop seizures/emesis

ketamine if you want the BP increased. Ideal for trauma

etomidate is a good default choice

Positioning

if you can manipulate the neck, get the patient in sniffing position

Placement of the tube

know your Comack-Lehane grade

you can pass the tube for grades I and II

you should use cricoid maneuvers, bougie, or VL if grades III and IV

Proof of placement

waveform capnography is the proof. I will also accept: the paralytic has worn off, and the patient is not dead (or talking, telling you to “get the fucking tube out of my mouth”).

Post-intubation management

very complicated topic to be discussed elsewhere

but, for starters, proper analgesia and sedation are necessary for competent care. I recommend liberal use of fentanyl. Give what you would give for a spontaneously breathing patient, and multiply by 3 or 4.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Intussusception

Intussusuh... intersele... intersuscep... interception? You know the fuck I mean. It’s in the title. I’m not spelling it again. Here’s everything you need to know about interception for the exams:

Epidemiology

Idiopathic interception is a disease of infants. 2/3 of cases are in patients 5-12 months old. Neonatal presentations are rare. Children 1-3 years old can still get this. Patients older than 3 who get intercepted probably have an underlying disease causing the intercepting. Adults who get interception probably have cancer. Males are more than twice as likely to get this than females. Unless otherwise stated, the rest of this review will be on your typical idiopathic interception in the patient aged 5-36 months.

Presentation

The most popular presentation is baby colic, crying in knees-to-chest position, followed by lethargy. I don’t know why the hell pediatricians hate the word “lethargic” so much, but apparently they are starting to believe it should only used in patients with interception.

A more specific scenario is a bowel obstruction picture in an infant >5 months old. Emesis is initially non-bilious and due to cranky baby GI tract, but progresses to bilious emesis due to obstructed baby GI tract. The age is crucial. If you have bilious emesis in the first month of life, this is midgut volvulus. On the exam, if you do anything other than call surgery immediately and call a CODE VOLVULUS, your patient explodes and you get the question wrong. Bilious emesis in a patient >5 months can still be midgut volvulus, but the probability becomes low enough you should do some doctoring before jumping to a consult.

Currant jelly stools is code for you diagnosed the interception too late. On the exam, it is synonymous with the disease, but realize that this is a late presentation, and it means the intestinal lining is already sloughing off. That’s bad.

Workup

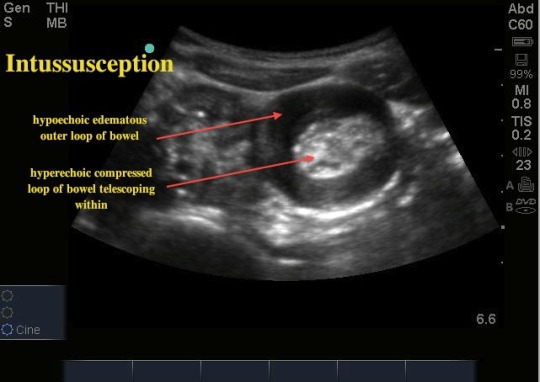

If interception is suspected, the best test to order is an ultrasound. The diagnostic sign is the “target sign:”

Just as good, and also acceptable, is XR with air or contrast enema. The diagnostic accuracy is comparable to ultrasound, and you get the added benefit of the gush of enema, which can cure interception.

Plain XR is not sensitive or specific enough, but there is a diagnostic sign that may show up on the exam: the “radiographic Dance sign” describes a relative lack of air in the right abdomen:

CT is going to be a wrong answer. We don’t irradiate babies in America.

Management

Decide if the patient is sick or not sick, perforated or not perforated. If any of the following exists, non-operative reduction of the interception cannot be done, and you should consult surgery immediately:

Unstable, toxic patient

Radiographic perforation (free air)

Perforation on physical exam (generalized peritonitis)

Otherwise, the first-line treatment is therapeutic enema done under fluoroscopic or ultrasonographic guidance. Disposition after a successful procedure is controversial, and some say observe for a bit and DC from ED, while others say admit. This won’t be tested. If the procedure is unsuccessful, admission for serial exams and surgical planning becomes necessary.

Atypical interceptions

The list for diseases that can cause interception is long. I think only these will be tested:

Meckel diverticulum: that rule-of-2 disease that presents as painless rectal bleeding in a patient aged 1-2.

Henoch-Schonlein purupura (HSP): That weird disease with gravity-dependent purpura that can cause ARF is rarely associated with interception, but examiners like to focus on this for some reason.

Cystic fibrosis

Cancer: In adults who are diagnosed with interception, there is >50% chance this is due to some intra-abdominal cancer.

When there is an atypical interception, which should be assumed in any patient older than 3, therapeutic enema is not recommended because it is unlikely to be successful. These interceptions have a surgical lead point and need surgical correction.

0 notes

Text

Cardiac Tamponade and Pericardiocentesis

Indications

Cardiac tamponade is the only clinical situation pericardiocentesis should be attempted in the emergency department

Not only should the patient be in tamponade, the patient should be dying from tamponade. The question stem must paint a true emergency with a patient in extremis.

In nontraumatic tamponade, pericardiocentesis can be attempted whether or not the patient has signs of life

In traumatic tamponade

Attempt pericardiocentesis if the patient has signs of life. Do NOT attempt pericardiocentesis if there are no signs of life.

If there is trauma, suspected or confirmed cardiac tamponade, and no signs of life, thoracotomy is the procedure.

Diagnosing cardiac tamponade

Beck’s triad is muffled heart sounds, hypotension, and jugular venous distension (JVD). It is very insensitive. Patients on the exam are likely to have hypotension and JVD. The exam often replaces muffled heart sounds with some other clue.

Let’s go through the individual signs associated with cardiac tamponade:

Muffled heart sounds: As America gets more obese and chronically sick, I hear muffled heart sounds every day. It means nothing to me.

Hypotension: on the exam, SBP <90 always means something very bad. Cardiac tamponade does not need to present with hypotension, and ideally you want to diagnose it before the patient becomes hypotensive.

JVD: This is the most reliable sign from Beck’s triad (shown below). Unless this is a trauma patient that is simultaneously in hemorrhagic shock, patients with cardiac tamponade will almost always have JVD.

Pulsus paradoxus: I hate this sign. First of all, there is nothing paradoxical about it. When you take a full breath in, and increase intrathoracic pressure, your SBP is supposed to drop. This normal physiologic property is exaggerated (defined as SBP drop >10 mmHg) in right-sided heart failure and/or obstructive shock. A better name for this sign would be SBPus dropus exaggeraticus. As you can imagine, it is difficult to accurately quantify in a distressed tachypneic patient struggling to stay alive; and, as mentioned, it is nonspecific and can occur in any scenario causing right-sided heart failure and/or obstructive shock.

Electrical alternans: this EKG finding (shown below) of QRS complexes that vacillate between two amplitudes every other beat is specific for cardiac tamponade. It is not sensitive or pathognomonic. Furthermore, you should not be diagnosing cardiac tamponade on EKG. This is analogous to diagnosing tension pneumo on CXR.

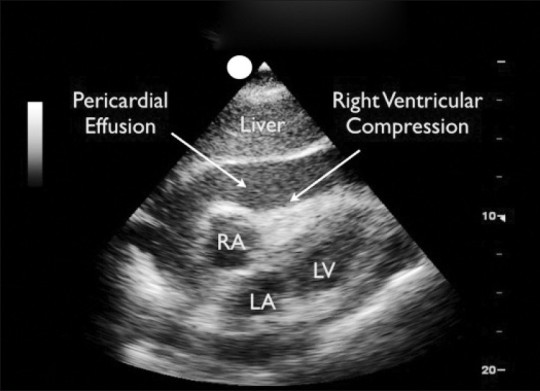

Ultrasound: fuck everything above. The real emergency physician has a gut full of gestalt, an ultrasound probe in the left hand, and a big ass needle in the right. Tamponade is an ultrasonographic diagnosis. In the right hands, ultrasound is 100% accurate. On the exam, the still image will be similar to this one (but without the labels):

I AM an Interventional Radiologist

In my opinion, the most important reason all emergency physicians should learn some basic ultrasound is to be able to diagnose cardiac tamponade within seconds. The subxiphoid view of the FAST exam is the first thing to master when learning ultrasound.

In the patient with penetrating thoracoabdominal trauma, your first view on your FAST exam should be the pericardial view. In a dying, hypotensive trauma patient with a hole in the trunk, finding and dealing with cardiac tamponade takes precedence over even finding hemoperitoneum. If the patient has a pulse, but is hypotensive with a pericardial effusion, ED pericardiocentesis is an appropriate response. Another acceptable (and probabaly better) answer is immediate OR thoracotomy. The exam won’t ask you to pick between the two.

In the non-trauma patient with respiratory distress, JVD, and hypotension, cardiac ultrasound should be performed because it will diagnose cardiac tamponade, and if absent, give clues about possible massive PE or cardiogenic shock. On the Boards, if you CT a hypotensive patient, you kill the patient.

In non-trauma patients, the following clues are meant to be interpreted as “suspect cardiac tamponade” when in the setting of hypotension and JVD:

malignancy (especially multiple myeloma)

ESRD (especially if uremic)

pericarditis

aortic dissection

The ultrasound findings of cardiac tamponade:

A big, scary looking pericardial effusion should be present in all cases, but by itself, is not sufficient to make the diagnosis. The size of the effusion does not predict emergency. Chronic effusions can be >1L and not cause hemodynamic compromise. Acute effusions of 100mL can be enough to cause hemodynamic compromise.

A heart that swings as it beats in a sac of fluid is highly suggestive of cardiac tamponade. This is “ultrasonographic mechanical alternans”.

The single finding that will define cardiac tamponade for the exam is pericardial effusion + paradoxical right ventricular collapse during diastole. Remember that the heart fills during diastole. In significant tamponade, the RV actually collapses during diastole, and this is no bueno. At this point, the patient will die unless that fluid is emergently drained.

The ultrasound is also vital in performing pericardiocentesis.

Blind pericardiocentesis has a complication rate of up to 50%, and when you stick needles into the mediastinum blindly, these complications can be catastrophic.

EKG-monitored pericardiocentesis is now always a wrong answer. It is cumbersome to set up, and I’m not sure how much safer it makes the procedure.

Ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis has a complication rate of ~5%. It should be used every time this procedure is done, as long as an ultrasound is available, and you know how to guide a needle with an ultrasound.

Contraindications

Pericardiocentesis is a lifesaving procedure with no absolute contraindications.

The big mistake is then if you do the procedure under non-lifesaving circumstances. This is a very dangerous procedure even with ultrasound and recognizing when it is more appropriate to transport the patient to the OR is essential.

Do not perform on a stable patient. SBP >90 should be a hard rule. If a patient has cardiac tamponade, but a good blood pressure, see if you can find an accepting surgeon before the patient becomes hypotensive.

Even worse is doing pericardiocentesis on a patient without cardiac tamponade. It does not matter how big the effusion is; if you tap the effusion and there is no tamponade physiology, you are doing a diagnostic pericardiocentesis, which should never be done by an ER doc.

A relative contraindication is cardiac tamponade caused by acute hemopericardium in the trauma or aortic dissection patient. The procedure is rarely successful because acute blood clots, and cannot be aspirated. A better answer in these cases is immediate OR transfer for thoracotomy. However, if that is unavailable as an answer choice, you are cornered into doing a likely futile pericardiocentesis. Doing an ED thoracotomy on someone with a pulse is still frowned upon by ABEM.

Testable points about the actual procedure

There is no standard way to do pericardiocentesis because this is an infrequent ED procedure not amenable to prospective studies and the creation of homogenizing guidelines.

If you are thinking about doing a pericardiocentesis, cardiothoracic surgery needs to be consulted. You are not asking for permission; you are doing the procedure, and notifying them of the consultation. They may save your ass if your procedure is unsuccessful, and they will be the service for definitive care if your procedure is successful.

If you have no ultrasound and are stuck doing this blindly, the most popular point of entry is between the xiphoid process and the left costal margin, aiming towards the left clavicle, and at a 45 degree angle into the body.

There is no standard way to do ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis. Use the probe to find the optimal spot where the pericardial fluid is the most superficial, deepest, and furthest away from other no-touchy structures. Note that the best view to diagnose pericardial effusion is the subxiphoid view, but this view CANNOT be used to guide a needle into the pericardium, because you would be guiding the needle through the liver. You must use either the apical view or some sort of parasternal view.

Draining even small amounts of fluid can have dramatic improvement in vital signs.

If you are sure the needle is within the pericardial space, you can use a Seldinger technique to place an indwelling catheter to buy even more time for transport to the OR, and prevent the need for repeat sticks if there is fluid re-accumulation. You can use the guidewire, dilator, and catheter from your trauma line kit. Just be sure you are in the pericardial space, and not within a cardiac chamber. Trying to dilate into the latter, I hear, is a fatality in the next Mortal Kombat.

0 notes

Text

"Toxic” Alcohols

The players

“Toxic alcohol” is a poor name for the classical trio of methanol, ethylene glycol, and isopropyl alcohol. I prefer the term “non-beverage alcohol” because one of them is not toxic at all.

The true toxic alcohols are methanol and ethylene glycol. These are deadly in small amounts. They both cause severe metabolic acidosis. Methanol causes blindness and brain damage in addition. Ethylene glycol causes a specific form of crystal-induced renal failure and brain damage in addition.

The fake toxic alcohol is isopropyl alcohol (isopropanol). ED treatment of this “poisoning” should not be different from ethanol poisoning, except to be extra sure that the ingestion was not a suicide attempt.

The in-between is propylene glycol, which is marketed as the “safe antifreeze” because ethylene glycol is such a nasty substance for our peds and veterinary population to get into. Propylene glycol is not as bad, but it is metabolized into lactic acid, and can also cause deadly metabolic acidosis. The most likely clinical scenario is iatrogenic propylene glycol poisoning in people needing large doses of benzodiazepines (in the ED, this is almost always your alcohol withdrawal patient), because propylene glycol is a preservative added to many IV drugs, including benzodiazepines. That’s all you have to know about propylene glycol for exams.

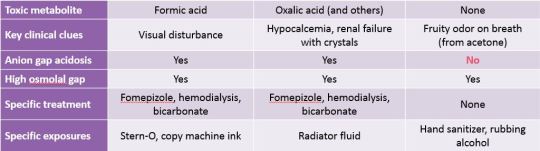

In summary:

Ethanol and isopropanol mainly get people drunk. The parent compound is the problem. You do NOT want to slow metabolism by giving fomepizole.

Methanol and ethylene glycol get people dead. The metabolites are the problem. You definitely want to slow metabolism by giving fomepizole (or ethanol), and then get the parent compound + toxic metabolites out of the body by hemodialysis.

The history

Exam questions will probably have to give you information about a specific exposure (e.g., patient drank moonshine, antifreeze, rubbing alcohol, etc.). Moonshine can be contaminated with methanol. Antifreeze often contains methanol or ethylene glycol. Rubbing alcohol often contains isopropanol.

The majority of toxic alcohol exposures are unintentional or recreational. These are typically adventurous alcoholics looking to break away from the mainstream either due to lack of financial resources or who-knows-why. These are typically less serious because there is usually some amount of ethanol on board, which is an antidote for toxic alcohols because enzymes will preferentially metabolize ethanol.

The vast majority of fatal overdoses on toxic alcohols are from suicide attempts, despite suicide attempts making up a minority of exposures.

Physical exam: tachypnea is fucking crucial

We kid about nurses documenting a RR of 18 or 20 automatically for everyone, but RR is the most underappreciated VS. For real-life clinical practice, you must be able to instantly recognize someone who is breathing 30 or above, and realize that that means badness.

Ethanol and isopropanol cause CNS depression without tachypnea. In severe overdoses resulting in coma, these drugs cause some respiratory depression.

Coma with tachypnea should scare you because it means intubation will not save the day. Most of the time, it means shock and/or severe metabolic acidosis is present. If this was a suicidal ingestion of unknown substance and there is CNS down and RR up, know that differential is ASA #1, and toxic alcohols #2; but you treat for both.

The common management pathway

After ABCs...

Determine if there is a chance you are dealing with methanol or ethylene glycol toxicity:

the obvious: there is mention of specific exposure in pt history

there is decreased LOC with unexplained tachypnea

there is unexplained metabolic acidosis on labs

If yes to any of the above, you should give fomepizole. You do NOT give fomepizole if you know the exposure is due to isopropanol. If you do this on the exam, you will bankrupt America even further, and get the question wrong.

After fomepizole, you should arrange for emergent hemodialysis and treat severe acidosis with bicarbonate. Serious exposures with serious presentations should be intubated and admitted to the ICU.

If fomepizole is not an available answer choice, ethanol is still acceptable. Ethanol is considered inferior to fomepizole because it is more difficult to titrate, has the side effects of intoxication, pancreatitis, gastritis, and hepatitis.

Activated charcoal and gastric lavage are officially poo-pooed for toxic alcohol ingestion on the exam. The evidence suggests that these tiny molecules are pretty quickly absorbed in the gastric mucosa and bind poorly to charcoal, making these therapies all-risk-and-no-benefit.

Specific tasting notes on the alcohols

I guarantee you that remembering the metabolic pathways for these alcohols makes you a bigger geek, but not any better of an emergency physician. Don’t do it (unless you are trying to become a toxicologist). Remember the following specific clinical features, toxic metabolites, adjunct therapies, and you are golden:

Methanol

Methanol becomes formic acid. Formic acid kills.

The specific features pointing to methanol toxicity is blindness and putamen/basal ganglia destruction

the classical symptom for methanol-induced blindness is blurry vision described as a “snowfield.”

the classical signs are afferent pupillary defect (due to CN II dysfunction) and optic disc hyperemia.

Folinic acid (folate) may have marginal utility in methanol toxicity. It is not an essential part of management, but if you don’t have other answer choices available, pick it.

Classically, Stern-O (canned heat) and copy machine fluid contain methanol.

Ethylene glycol

Ethylene glycol becomes a bunch of deadly acids. Oxalic acid gets special mention, and is specifically tested because:

it gunks up the kidneys, causing acute renal failure

it can be seen in the urine as envelope shaped crystals

it binds calcium, causing hypocalcemia

Thus, the specific features for ethylene glycol toxicity that you should remember are acute renal failure and hypocalcemia. These are rarely the cause of death. How ethylene glycol kills, other than metabolic acidosis, is cerebral edema.

Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) is the marginally useful specific adjunct therapy for ethylene glycole. Like with folate for methanol, use only when there are no other answer choices available

Classically, antifreeze and radiator fluid contain ethylene glycol.

Radiator fluid (whether or not it contains any ethylene glycol) glows under woods lamp due to other additives. Normal urine glows under woods lamp about 1/3 of the time. Hence, glowing urine means nothing, and should not be used diagnostically.

Isopropanol

Isopropanol becomes acetone. This is not an acid, and this is not toxic. You want this to happen. Let it happen. Don’t give fomepizole. Got it? Good.

A feature unfairly attributed specifically to isopropanol is hemorrhagic gastritis. We all know from our experience with alcoholics that this is not specific to isopropanol in real life.

Classically, rubbing alcohol and hand sanitizer contain isopropanol.

Specific studies

EKG

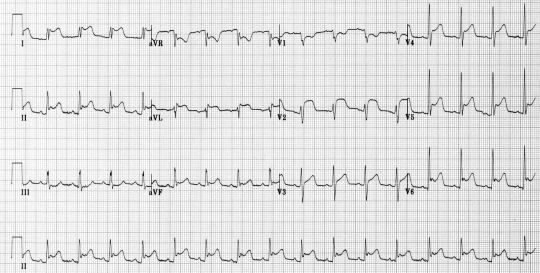

Severe acidosis causes widening of the QRS. It is definitely time to push bicarb when this happens.

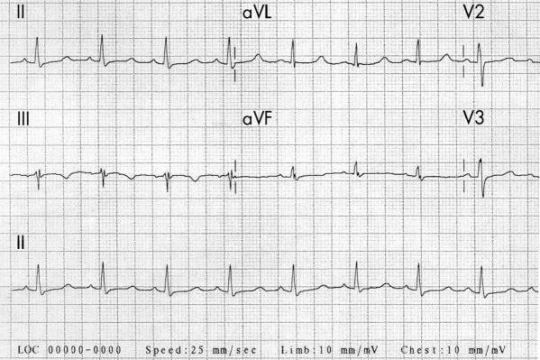

Hypocalcemia causes prolongation of the QTc without any prolongation of the T wave (see below). As a theme: hypocalcemia prevents muscle repolarization (which is represented by the T wave in cardiac muscle); this is why there is tetany, positive Chvostek sign, and positive Trousseau sign in skeletal muscle.

Blood gas

A low pH with low bicarbonate defines metabolic acidosis, which is a feature of methanol and ethylene glycol toxicity.

Isopropanol does not cause acidosis

Serum chemistry

Hypocalcemia suggests ethylene glycol toxicity

Acute renal failure also suggests ethylene glycol toxicity

Low bicarb is metabolic acidosis

Gaps

Alcohols will cause a significant osmolol gap, distinguishing it from almost every other toxic ingestion. Methanol, ethylene glycol, and isopropanol will all cause an acutely elevated osmolal gap.

Only the toxic alcohols: methanol and ethylene glycol will cause an elevation in anion gap. Isopropanol does not.

Alcohol levels

most ED labs only have an ethanol level

a few labs have a fast methanol level

no ED has an instant ethylene glycol or isopropanol level

as a rule:

don’t try to order or wait for levels for the non-beverage alcohols

a high ethanol level does not rule out co-ingestion of toxic alcohol. Once again, look for that tachypnea as an early clue that something is off.

Stripped down, once more:

Methanol, ethylene glycol

metabolized into acid = toxic

tachypnea

High anion gap + high osmolal gap

Tx: fomepizole, hemodialysis, bicarbonate

Methanol: formic acid; blindness

Ethylene glycol: oxalic acid; renal failure, hypocalcemia

Isopropranol

metabolized into acetone = nontoxic

high osmolal gap; normal anion gap

supportive care only

Wrong answers

fomepizole for isopropanol

activated charcoal or gastric lavage for any alcohol ingestion

woods lamp to urine (you might as well drink it if you’re that desperate to look smart - don’t be that guy)

In chart form:

#emergency medicine#board review#toxic alcohol#methanol#ethylene glycol#isopropanol#isopropyl alcohol#toxicology#fomepizole

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

CNS Infections

The Differential

Meningitis

Encephalitis

Brain abscess

In reality, meningitis and encephalitis in the emergency medicine world can be clumped into a category of meningoencephalitis (ME), and it’s pointless for us to split hairs. This is a CT-negative CNS infection.

Brain abscess (BA) is separate, because it is a CT-positive CNS infection, which commonly causes a focal neurologic deficit, a rare feature in ME.

History and Physical

Fever, headache, altered mental status, stiff neck, seizures. The history for ME on the exam will include enough of those 5 things to make it obvious. If you can’t suspect the diagnosis on the exam, you are a bad doctor. If there are no focal neurological deficits, you can pursue an LP to diagnose ME.

If there are focal neurological deficits, with (for example) fever, headache, and AMS, you should suspect a BA, and obtain a head CT.

Here are some specific details that might show up in the question stem and what they mean:

Patient is older than 50, or is in the middle of a bad foodborne outbreak: you must suspect and cover for Listeria monocytogenes.

There is a Bell palsy or vesicular lesions: suspect and cover for HSV

There is rapidly progressing petechiae or purpura: this is a feature of meningococcemia. This can occur with or without meningitis.

Patient in college dorm or military barracks: meningococcus.

Playing with monkeys in a laboratory: Herpes B virus

Some weird shit about using a nasal irrigation system, or swimming in a body of fresh water in hot weather: amebic ME, and specifically, Naegleria fowleri

HIV patient: you should be treating empirically for Cryptococcus and obtaining a head CT (thinking about toxoplasma ME)

A special note about Brudzinski and Kernig: these signs show up on exams. They are not sensitive or specific for CNS infection. They are specific for meningeal irritation, which is nowadays more often caused by SAH. They are about 5% sensitive. In real life, I never check for these signs because they are so useless. Play the game, and know them for the peri-exam period:

Brudzinski: Passively flex the neck. Sign is positive if the pt’s knees and hips involuntarily flex.

Kernig: Passively flex hip first, then passively extend the knee. Sign is positive if the pt cannot tolerate full extension of the knee.

The lumbar puncture

The crazy overly-complicated lumbar puncture rules are over.

You never do an LP before antibiotics if you suspect a CNS infection. This was controversial before, but is now an absolute law. I’m not going to get into the reasoning. If you do an LP before giving antibiotics on the exam, you killed your patient.

You do not have to worry about brain herniation if the concern is for ME. If a CT is not otherwise warranted, you do not have to get a head CT before LP. Obviously, if there is focal neurological deficit, then you should suspect BA, and order the head CT.

The LP is not vital. It will not save your patient’s life. If the question stem gives you a contraindication: patient is unstable, actively seizing, severely coagulopathic, has overlying cellulitis, or cannot follow commands, don’t get the LP.

Textbooks make way too much of a big deal about LPs. You are likely to be led astray if you put LP results above your clinical gestalt. First of all, you cannot rule out CNS infection with an LP; you cannot with any certainty decide bacterial vs. viral based on cell count. Having said that, here are some rules that will always be true on the exam:

Cell count: If WBC >1,000 and neutrophils (or PMNs) dominate, it is bacterial. If WBC is in the hundreds, and lymphocytes dominate, it is viral.

Glucose: If it is <40, it is bacterial.

Protein: It is high in all CNS infections and even in non-infectious CNS disease. E.g., in GBS, there is classically high protein with normal cell counts.

Bloody CSF: Assuming you are fairly sure the pt has an infection and not SAH, this is a clue for HSV, which likes to cause a nasty hemorrhagic ME.

Gram stain

gram positive diplococci or “lancets”: Pneumococcus. This is by far the most common bacterial meningitis

gram negative diplococci: Meningococcus

Weird shit to order in certain circumstances:

India ink: get in patients with HIV. This will allow for rapid diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis, but can be falsely negative 50% of the time. Much more sensitive is a cryptococcal antigen test, but this takes much longer.

HSV PCR: get in patients with mention of active or recent shingles, Bell palsy, or HSV outbreak

Wet mount: get in patients exposed to nasal irrigation systems or warm bodies of fresh water. This will allow for the detection of live amoeba, which will not be seen on routine gram stain or cultures.

Treatment

The core empiric therapy that you will give to every adult who can tolerate:

Ceftriaxone 2g IV

Vancomycin 15 mg/kg IV

Dexamethasone 10mg IV. This should be given with, or before antibiotics. Never after.

For adults older than 50: add ampicillin 2g IV to cover Listeria monocytogenes

For brain abscesses: add metronidazole IV and consult neurosurgery

Low yield, but may show up:

If there is any concern for a herpes ME, add acyclovir IV.

Treatment for cryptococcal meningitis is amphoteracin B + flucytosine.

Treatment for amebic meningitis is at least amphoteracin B and prayer.

Treatment for toxoplasmosis is pyrimethamine-sulfadiazine.

Contact Chemoprophylaxis

The drug-of-choice for healthcare providers is a full dose of calm-the-fuck-down.

There are two contagious organisms that can spread (not very easily) by droplets: meningococcus and H. influenzae. Together these account for about 25% of cases of bacterial meningitis in the U.S., which currently occurs at a rate of about 4 per 100,000. Over half are caused by pneumococcus, which is not contagious.

There is no common situation where a healthcare provider should need chemoprophylaxis, but should you intubate a patient without a mask or perform mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, a dose of abx might be warranted.

For household contacts that share meals or rooms with the patient, a dose of abx is warranted:

The DOC is oral rifampin (4 days for H. flu, 2 days for meningococcus)

Also accepted for meningococcus only: single-dose oral ciprofloxacin

In pregnancy: rifampin and Cipro are contra-indicated; give single-dose IM ceftriaxone instead

If you know the organism is pneumococcus, no chemoprophylaxis is needed.

Pitfalls

In a patient with headache, fever, and someone you may have considered for a CNS infection, but also has obvious sinusitis or otitis, do not be relieved that this is “just” sinusitis or otitis. Your suspicion for bad shit should be even higher because sinusitis and otitis is often the preceding infection that seeds the CNS.

You cannot rule out CNS infection with an LP

Don’t delay antibiotics for the LP

Do not give chemoprophylaxis unecessarily.

Real life lesson not applicable to the exam: I do not believe in this whole bacterial vs viral meningitis distinction bullshit. That is the world of upstairs. Patients in the ED should be divided into septic (something needs to be done now) and aseptic. Reasoning:

TB and Lyme are bacteria that cause meningitis. They are aseptic, and clearly have a different presentation than the examples below.

HSV is a virus; and Naegleria is an ameoba. Both cause ME, both are treatable, and both are more often fatal than bacterial meningitis. They are acute diseases that result in a septic patient.

Get a good H&P, and treat the patient, not the LP results.

#emergency medicine#board review#cns infection#meningitis#encephalitis#brain abscess#meningoencephalitis#lumbar puncture

0 notes

Text

Cerebrovascular “Accidents”

The diagnosis of “cerebrovascular accident” or “CVA” should no longer be used by emergency physicians. The term CVA communicates the fact you are too lazy or too dumb to differentiate between two opposite processes: bleeding and clotting.

Is it bleeding?

The umbrella term we should use is intracranial hemorrhage (ICH). The term “hemorrhagic stroke” should be forgotten because it tempts doctors to apply the term stroke to a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). SAH is not a stroke.

The starting point for every acute atypical headache and/or acute neurological deficit must be the non-contrast head CT (NCHCT). “Worst headache of life” is not a necessary component of ICH. Any acute onset, severe headache that is not typical of previous headache pattern warrants CT evaluation.

SAH