Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Statement of Faith: A Revision

Eric Winn, April 2016

It was early fall, 2000. I was twelve, moderately naive for my age and on the brink of becoming severely and hopelessly indoctrinated.

I sat in the church banquet hall with a few dozen of my peers, each of them joining me in the rite of passage known as confirmation, or as we liked to call it, the opportunity to be sanctioned as members of an otherwise adult organization. From that point forward we would be referred to as confirmands, achieving membership only after completing the program. A part of me was excited to make my affiliation with the church official, but another part of me cried out for real answers to unanswered questions. The second part was the one I actively repressed. Although I had some reservations about my faith at the time, I understood that challenging any aspect of the religious enterprise would not only constitute heresy, but also disrespect.

The excited part of me, however, enjoyed being in the company of relatives and friends as we gathered for the confirmation orientation ceremony that would include food, introductions, and the official assignment of our mentors. Gazing around the room, I played spectator to the various interactions of people gathering in the hall: the families of my peers, the dressed-up clergy, and the good-humored church staff. The air was heavy with infectious and unbridled enthusiasm. I began to realize that the adults in the room shared some vaguely-defined quality seemingly far beyond my few years; they surely possessed the wisdom that would undoubtedly come with my ascension to church membership and a lifelong commitment to serving Christ. I was, at least in principle, fully dedicated to the project of learning to view the world through the lens of faith. I stood at the precipice with my arms open. All I needed was a slight breeze of validation.

As the event began, everyone slowly took their seats at their assigned tables. A gaunt, middle-aged man reaching teetering heights stood up at the front of the hall, calling for everyone’s attention. With his characteristic geniality, the sincerity of which was an abiding suspicion of mine, the minister gave an effusive welcome and announced he would be taking questions from the confirmands at the end of the night. In an attempt to encourage well-thought-out and potentially challenging queries, he passed out slips of paper so we could spend the evening thinking of a single most-pressing question and anonymously drop it into a tithing bowl at the front of the room. I remember my excitement boiling over at the prospect of unleashing my curious mind under the cover of anonymity. But with so many thoughts rattling around in my head, it was difficult to come up with a single question that would satiate my reeling mind. I was so distracted by my thoughts that I effectively blocked out the rest of the evening.

As the question time drew nearer, I frantically scribbled mine down at the last second and tossed it into the bowl. I reclaimed my seat as the minister began selecting and reading aloud the submissions. Waiting for mine to be drawn, an awkward cocktail of emotions began to stir—a curious blend of eagerness and anxiety. Then it happened. He read aloud: “If God created everything, then what created God?” My words dripped with philosophical overtones of regressions to infinity. He retorted with a chuckle, echoed by several others in the hall. I blushed and shifted in my seat, my embarrassment detectable to any stray glance in my direction. Was my question really that stupid? Maybe he did have an answer after all, I thought. A small part of me wanted him to reveal my ignorance. At least then I might fully relinquish any doubts and accept that faith really was the path to a deeper understanding of the world—an understanding I so desperately craved.

The minister responded after a brief moment of apparent internal head scratching. “This is one of those questions we really can’t know the answer to…” For a moment I felt impressed by his candor. Did he really just admit that he didn’t know? But I should have known this would not be received as an adequate response coming from a cleric; it of course lacked the lure of superstitious charm that was so obviously craved by his audience. He then concluded, adopting a posture swollen with confidence: “But what we do know is that God is eternal. He has always existed and therefore didn’t need a creator. Some ideas are just too big for us to wrap our heads around. This is why we have to trust in God. We must have faith.” I was thoroughly let down. Was there really no other response on offer? At that exact moment it was revealed to me that faith was nothing more than a dodgy little lifeline, conveniently allowing for a complete dismissal of critical thinking. Any reservations I harbored up until that point were confirmed by a landslide of epiphanies. The entire routine was clearly contrived—engineered to instill a flock mentality. Looking around at the satisfied faces dotting the room, my irritation mounted as those under the shepherd’s watch mindlessly nodded in a bizarre show of obedient agreement.

The question and answer session wore on as the master of deceit continued knocking out question after question, confidently providing answer after answer, as if he were drawing from a deep well of untapped wisdom that only he had been given divine access to. But I knew this couldn’t be true. This was really just an exercise in peeling back the dubious layers of the reverend charlatan’s brain—the more he continued, the less credible he became. But I was seemingly alone in this interpretation of his shtick. Everyone else acted as though their beliefs were somehow being vindicated to an ever-increasing degree with each word that passed through this man’s lips. His continuous recourse to faith at the expense of coherency was the elephant that refused to leave that room.

I grudgingly participated in the rest of the program and regarded the experience as nothing more than a window into the depravity of the host institution. At a minimum, blind faith and subservience seemed a sure path to moral confusion, but appealing to the credulity of young children to increase church membership effectively crossed the line between superficially tolerable and ethically reprehensible. The swindler’s scale had finally tipped in favor of absolute scandal.

I drafted a statement of declared faith and ensured that it would guarantee everyone else’s satisfaction—the minister and mentors, my fellow confirmands and my own family. I communicated it aloud from the sanctuary stage to an impressively attentive and beaming congregation. It was, in fact, the most disingenuous avowal I would ever make. The indignity was enough for me to throw in the towel, if only in a behind-the-scenes kind of way. For me the game had been called, but I was letting the clock run out as a formality. My involvement with the church waned significantly in the ensuing years and I was scarcely more than a name on the church’s register by the time high school graduation rolled around. I was twenty-two years old when I formally requested to end my membership.

I consider this reflection to be a repudiation of the “statement of faith” I wrote as a young, conflicted child of the nineties, a child who found himself preoccupied for the second time with a blank sheet of paper. Much like the first time, the sheet could have been transformed into an ambitious and challenging inquiry. Or perhaps into an expressed appreciation of how precious life is given the very short time we are afforded. It could have become a testament to the unfailing and unconditional love of my family, or even an expression of the overwhelming sense of humility afforded to me by chance in a vast and mysterious and unsolved universe. Regrettably, it was transformed instead into a doctrinaire expression of the stale reverberations of a religious echo-chamber.

The statement, in its original form, is preserved in the nostalgia of an aging scrapbook in a closet in my childhood home—an admittedly cheesy digest of my youth in photos, and birthday cards, and various other sentimental relics. I haven’t revisited the document in my adulthood, and perhaps this is due to some subconscious reluctance to relive this memory in an explicitly tangible way. A part of me always felt guilty—maybe even self-loathing—about the lie that exits in my past as both a written and spoken testament of religious faith. Re-writing the statement was a way for me to recompense my younger self, and, having since outgrown the timidity of my youth, express the sincerest contemplations of that twelve-year-old boy who may have felt like insincerity was simply a part of growing up.

There exists an ancient maxim that I never could properly source, but goes something like this: “The more you learn, the more you realize how little you know.” The ability to apprehend the limits of one’s knowledge and admit that “I don’t know” exists as the great guardian of intellectual progress. The true mark of an educated person is, after all, manifestly in how you think, never only in what you know. The binocular-like lens through which the faithful view our world, peering into the murky realm of superstition, will forever see them stumbling into the chaos and hubris of religious conviction, perpetually leaving unfocused the beauty of the reality that lay directly before them.

I’ve come to understand that my reeling mind can only be satiated by our most essential discipline—the pursuit of understanding and truth, founded on the virtues of science and philosophy. Answers, therefore, cannot be assumed—they must be discovered. The greatest insights of all time may very well lie in the refinement of the pursuit itself, because regardless of whether or not we find an answer, the question is always sure to exist.

But this story remains incomplete. A fresh page is now numbered, my fingers resting patiently on the keys. A familiar cocktail of emotions once again marks the occasion. My future exists now as a flashing cursor, awaiting the next keystroke.

0 notes

Text

Transgenderism as a Mental Disorder: My Response to Grace Pokela and The Huffington Post

Eric Winn, March 2017

High School teacher Grace Pokela and The Huffington Post contributor Curtis Wong have one thing in common: an equally toxic brand of argumentation. Wong’s article, “Biology Teacher Expertly Smacks Down Transphobe Who Cited Science”, and the Facebook post that inspired it, has secured a bandwagon of support highlighting the remarkably contagious nature of bad thinking.

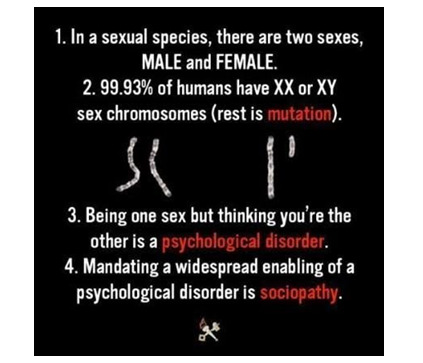

According to the article, Pokela, a high school biology teacher by profession and self-described social justice warrior by duty, stumbled across a meme several weeks ago that described transgenderism as a psychological disorder. Apparently, hordes of pesky transphobes had been piling straws on her back for quite some time, and according to Pokela, this was the final one. Her social justice instincts immediately fired up and our warrior readied herself for battle. The meme reads as follows:

Her response to this was in the form of a Facebook post that went viral. Here it is in all of its glorious and incoherent tedium:

To preface, I’ll tell about my initial collision with Wong’s article in The Huffington Post. The link to the piece was sent to me via text message from a good friend who was admittedly fishing for a reaction. Well, needless to say he’s getting one now.

After reading the article, I immediately texted my friend back “This is why you wouldn’t take a high school biology teacher seriously in a philosophy seminar”. In my mind, this was an appropriately illogical response to Pokela’s equally illogical argument. My intention was to convey irony as a point of humor. But the reason I am pointing this out is because I think it will be instructive. Let’s start by analyzing my text message and see if we can extrapolate anything useful.

As we know, logic is a branch of philosophy and is the foundation for argumentation; the gold standard of philosophical discourse is to be as logically consistent as possible. In mentioning the broader domain in my message, my aim was to make a tacit reference to this narrower discipline. I could have just as easily said “because someone is a high school biology teacher, they cannot make a valid argument.” This is essentially the same claim but without the linguistic flair. It is a fairly straightforward example of a non-sequitur in an informal sense, which is to say the conclusion does not follow logically from the premise. Why? A person’s profession does not dictate whether or not they can make a valid argument. It is no sillier to say “because someone is a high school biology teacher, they cannot ride a bike.” But my message was also a red herring. It effectively diverts attention away from the original issue.

Before we delve into a more lengthy dissection of Pokela’s argument, it is necessary to highlight the distinction between how a person thinks and what a person thinks. By latching exclusively onto the body of facts she cites about biology as a reflection of what she thinks, those persuaded by Pokela’s rhetoric seem to be confused about this distinction and its relevance. It is also true that what she thinks could mean her opinion about the classification of transgenderism as a psychological disorder. But I have no interest in addressing the specific issue of transgenderism. To be clear, I only want to address the substance and validity of her argument.

As a precursor, it is true that I see her inability to argue effectively as an egregious disservice to those who argue in favor of her position. Her post is the perfect example of how to set yourself up to lose an argument while simultaneously ruining your credibility. People who agree with her that transgenderism is not psychological disorder should be recoiling in horror in response to her post. Maybe I am one of them, hence my motivation to publish my own response. Or maybe I just see her as an easy target and therefore an easily scored point for the opposing side. Either way, in an attempt to take down a toxic and ineffective interlocutor on the subject, consider this criticism to be of service to both sides.

First we’ll briefly focus on the information Pokela presents in her post as a reflection of what she thinks.

From the onset, her post becomes littered with facts so irrelevant to the issue that the reader is left wondering what it is she is even arguing. She drones on about environmental circumstances and spontaneity as factors that can determine sex in a multitude of species other than human beings. It’s not until about halfway through that she begins addressing human biology in an agonizingly smug shift in focus. It is precisely here that her argument loses all traction in two major ways.

First, Pokela immediately begins pointing out various anomalies that are classified as either deficiencies or mutations, leading us to believe that she might be fleshing out a causal relation between these aberrations and transgenderism. But she instead fails to mention any link at all, leaving us completely in the dark. Her argument continues to go absolutely nowhere.

Second, she begins to muddy her language to the point of incoherency. For example, she says that “You can be male because you were born female, but you have 5-alphareductase deficiency and so you grew a penis at age 12.” This is totally unintelligible in a grammatical sense. How can you be male because you were born female? This is tantamount to saying “you are a boy because you are a girl.” To be clear, this is not due to some fundamental misunderstanding of biology on my part—to the contrary. It is an obvious bungling of language on the part of the biology teacher. Allegedly, what she meant to say was that “You can be male even though you were born female because you have 5-alphareductase deficiency…” For someone who touts her credentials as an educator, this is an unforgivable error in syntax. Yet she continues to drive further into the ditch. Astonishingly, every subsequent sentence commits a similar syntactical error.

But if we hone in on her specific claim that you are born female and later become male if you have 5-alphareductase deficiency, we can identify a curious sleight of hand. Pokela shifts from discussing hard biological facts to that of gender identity, a much more subjective phenomenon. Her claim is that if you are born without a penis, and therefore in many cases raised as a girl until puberty, you are biologically female. From a psychological standpoint the child will most likely believe they are female, but even a person with 5-alphareductase deficiency is chromosomally male from birth, meaning they have an X and a Y chromosome. There is no hard biological shift in sex once puberty sets in, merely the emergence of male genitalia. Once again, every subsequent sentence commits the error, blurring this crucial distinction.

In the end, I don’t care that her mind is a receptacle for facts about biology. The ability to recite a textbook isn’t a measure of merit in an intellectual sense, and using facts to support an argument that are patently irrelevant to the issue is an intellectual disgrace. Her entire post proves to be nothing more than a giant red herring. She successfully diverts the attention of the reader away from the debate about transgenderism as a psychological disorder, shifting the focus instead to discussions about the nature of things like slime mold. Pokela also posits a false inference in the form of a non-sequitur, namely that because biological abnormalities occur in some number of humans, transgenderism is not a psychological disorder.

We’ll now shift the focus to how she thinks.

Whatever her opinion, as a starting point I could really only care about her ability to reason objectively and make a valid argument. The bottom line is that if she cannot establish credibility on these two points, then her position on the issue is simply not supported by her argument. In the context of her Facebook post, she has proven her inability to do both.

Pokela’s argument actually takes two forms, one using bigotry as the premise, the other using naturalism. Removing all the clutter, the crux of her argument comes in the last two lines of her post: “Don’t use science to justify your bigotry. The world is way too weird for that shit.” There is a lot embedded in these two lines, so let’s break them down.

The first line, “Don’t use science to justify your bigotry”, is a fairly loaded and misguided injunction. It seems that she acknowledges the scientific legitimacy of the meme, namely that there are two sexes in a sexual species, male (XY) and female (XX), and that any deviation from this as a “norm” is considered to be a mutation. But this is where she begins to incorrectly perceive the encroachment of bigotry onto what are otherwise sound scientific facts. The meme claims that because transgendered people do not psychologically identify with their chromosomally determined sex, they are suffering from a psychological disorder. This is a claim about mental health. If it is true that transgenderism is a psychological phenomenon that deviates from the “norm” and causes profound emotional suffering, then transgenderism seems to fit the bill of a mental health disorder by definition. But the debate is far more nuanced than that. The opposing rationale considers the idea that social attitudes and treatment options and their viability must also be considered, lest we risk further stigmatization of transgendered people. Therefore, all we are dealing with is a clash of opinions surrounding an official classification—a clash that quickly becomes an exercise in pragmatism. It is clear which side of the divide Pokela is on, and she’s clearly not arguing against classification for the sake of being pragmatic—she’s arguing in the name of biology.

At this point the errors in her perception of bigotry should also be clear. To be a bigot is to be intolerant toward those who hold different opinions, not merely to be the purveyor of a different opinion. The meme Pokela responded to is not an explicit display of intolerance. The denunciation of an opposing opinion as bigotry does not mean the opinion is bigoted just because one says so. I could say that you are a bigot because you don’t agree with me that Duran Duran is the greatest pop band of all time. Not only would I sound like a priggish brat, but this would be an embarrassing error in semantics. It would also be a curiously intolerant position for me to take. Arbitrarily redefining words in an incoherent way, in this case by defining bigot as “a person who has a different opinion than me”, should automatically annul the argument. It is ironic that in calling others bigots simply because they disagree with her, Pokela actually becomes perceptibly more bigoted herself. And in her case, I suspect this was not an intentional injection of humor.

But Pokela is a master wielder of vacuous trigger terms. She intentionally uses words like “bigot” and “transphobic” to rouse her audience without any evidence to back up her claims. It is her way of controlling the conversation by silencing dissent. To those who are sensitive enough to understand that real bigots and real transphobes should be ridiculed and marginalized, but not incisive enough to recognize the bully teacher in righteous clothing, her rhetoric succeeds. This is how you play tennis without the net. By preaching to generally impressionable people in this way, regardless of how vitriolic she might be, her victory is all but guaranteed each time she steps foot onto the court.

The second line of her argument, “The world is way too weird for that shit”, backed by all the garbled bio-facts that precede it, contains an implicitly embedded argument that goes as follows: “Because transgenderism is a natural phenomenon, it is not a disorder.” This argument falls victim to a loose interpretation of the appeal to nature fallacy, which states in a basic sense that it is fallacious to make a value judgment about something based on its natural properties. An obvious example is rape. Rape is natural. Most species would not reproduce if it weren’t for non-consensual intercourse. This is also true for our earliest ancestors. This truth, however abhorrent, is not in conflict with the fact that rape is immoral and illegal in most of the world. But we aren’t dealing with a moral question when it comes to transgenderism. Again, as a biological and psychological phenomenon, we are debating its official classification in the context of mental health. The truth is every mental health issue that is classified as a disorder occurs naturally. There is nothing artificial or simulated about depression or schizophrenia. These are scientifically understood disorders that emerge under certain conditions within certain biological systems. Even a delusion—and some will argue that transgenderism is exactly that—is still a product of the internal workings of a biological system. To suggest that transgenderism is not a psychological disorder simply because it is an expected consequence of “weird” biological anomalies is simply missing the point.

But this is also an example of the special pleading fallacy. This fallacy occurs when an argument posits an exception to a generally accepted rule without justifying the exception being made, similar to holding a double standard. As alluded to before, there is no reason to think that transgenderism is anything but a psychological phenomenon. It is true that transgenderism—or gender dysphoria as it is commonly referred to in the mental health community— is a conflict between perceived identity and chromosomally determined sex. There are no social or professional misgivings about labeling numerous other psychological issues as disorders, but Pokela makes an overt exception in the case of transgenderism with no evidence or valid argument to justify her exception.

I’ll now attempt to accomplish in three sentences what Pokela failed to accomplish in the half-page fact-salad she vomited onto her Facebook page. If I was to defend her position and that of her sympathizers, my argument would go as follows: The official classification of any psychological disorder is based on clinical research and the resulting consensus of mental health experts. Currently, the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) published by the American Psychiatric Association and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) published by the World Health Organization do not recognize transgenderism as a disorder. Therefore, officially, transgenderism is not a psychological disorder.

This is one example of how she could qualify her position successfully. It is important to always remember Ockham’s Razor, which states that when competing hypotheses emerge, the one with the fewest assumptions should be selected. In other words, the hypothesis that offers the simplest explanation is usually the best. Convolution presents little more than an opportunity to fail, and Pokela seized the opportunity.

To conclude, I’ll highlight a brief quote from Wong’s article in The Huffington Post:

“Pokela, who is originally from South Dakota, told The Huffington Post that she felt compelled to respond to the Facebook user because of the amount of conservative voters who she felt had “manipulated facts” to fit their agenda on social media. Based on the information presented in the meme, she added, it was clear that the user who posted it “wasn’t a scientist or an educator, and in fact had no interest in science” at all.”

Instead of breaking the excerpt down as part of another lengthy analysis, I will pose a very simple question: How is it clear that the person who posted the meme wasn’t a scientist or an educator and had no interest in science at all? I’ll leave this to the better faculties of the reader to ponder. Pokela did say in the article that she hopes her post will “empower” others. One can only wonder what degree of intolerance and anti-intellectualism she hopes to empower others with, exactly. Judging by the number of responses to her post, thousands have already been infected by her rhetoric. The rest of us can’t help but let out a nervous laugh.

In the end, my advice to Grace Pokela would be this: Don’t use science to justify your bigotry. The world will call you out on that shit.

0 notes