Text

No!!! That is how Narcisso die!

A depressed alchemist brews a love potion, so he can love himself again.

8K notes

·

View notes

Photo

BASICS:

Genres:

Alternate World: A setting that is not our world, but may be similar. This includes “portal fantasies” in which characters find an alternative world through their own. An example would be The Chronicles of Narnia.

Arabian: Fantasy that is based on the Middle East and North Africa.

Arthurian: Set in Camelot and deals with Arthurian mythology and legends.

Bangsian: Set in the afterlife or deals heavily with the afterlife. It most often deals with famous and historical people as characters. An example could be The Lovely Bones.

Celtic: Fantasy that is based on the Celtic people, most often the Irish.

Christian: This genre has Christian themes and elements.

Classical: Based on Roman and Greek myths.

Contemporary: This genre takes place in modern society in which paranormal and magical creatures live among us. An example would be the Harry Potter series.

Dark: This genre combines fantasy and horror elements. The tone or feel of dark fantasy is often gloomy, bleak, and gothic.

Epic: This genre is long and, as the name says, epic. Epic is similar to high fantasy, but has more importance, meaning, or depth. Epic fantasy is most often in a medieval setting.

Gaslamp: Also known as gaslight, this genre has a Victorian or Edwardian setting.

Gunpowder: Gunpowder crosses epic or high fantasy with “rifles and railroads”, but the technology remains realistic unlike the similar genre of steampunk.

Heroic: Centers on one or more heroes who start out as humble, unlikely heroes thrown into a plot that challenges them.

High: This is considered the “classic” fantasy genre. High fantasy contains the general fantasy elements and is set in a fictional world.

Historical: The setting in this genre is any time period within our world that has fantasy elements added.

Medieval: Set between ancient times and the industrial era. Often set in Europe and involves knights. (medieval references)

Mythic: Fantasy involving or based on myths, folklore, and fairy tales.

Portal: Involves a portal, doorway, or other entryway that leads the protagonist from the “normal world” to the “magical world”.

Quest: As the name suggests, the protagonist in this genre sets out on a quest. The protagonist most frequently searches for an object of importance and returns home with it.

Sword and Sorcery: Pseudomedieval settings in which the characters use swords and engage in action-packed plots. Magic is also an element, as is romance.

Urban: Has a modern or urban setting in which magic and paranormal creatures exist, often in secret.

Wuxia: A genre in which the protagonist learns a martial art and follows a code. This genre is popular in Chinese speaking areas.

Word Counts:

Word counts for fantasy are longer than other genres because of the need for world building. Even in fantasy that takes place in our world, there is a need for the introduction of the fantasy aspect.

Word counts for established authors with a fan base can run higher because publishers are willing to take a higher chance on those authors. First-time authors (who have little to no fan base) will most likely not publish a longer book through traditional publishing. Established authors may also have better luck with publishing a novel far shorter than that genre’s expected or desired word count, though first-time authors may achieve this as well.

A general rule of thumb for first-time authors is to stay under 100k and probably under 110k for fantasy.

Other exceptions to word count guidelines would be for short fiction (novellas, novelettes, short stories, etc.) and that one great author who shows up every few years with a perfect 200k manuscript.

But why are there word count guidelines? For young readers, it’s pretty obvious why books should be shorter. For other age groups, it comes down to the editor’s preference, shelf space in book stores, and the cost of publishing a book. The bigger the book, the more expensive it is to publish.

General Fantasy: 75k - 110k

Epic Fantasy: 90k - 120k

Contemporary Fantasy: 90k - 120k

Urban Fantasy: 80k - 100k

Middle Grade: 45k - 70k

YA: 75k - 120k (depending on sub-genre)

Adult: 80k - 120k (depending on sub-genre)

WORLD BUILDING:

A pseudo-European medieval setting is fine, but it’s overdone. And it’s always full of white men and white women in disguise as white men because around 85% (ignore my guess/exaggeration, I only put it there for emphasis) of fantasy writers seem to have trouble letting go of patriarchal societies.

Guys. It’s fantasy. You can do whatever you want. You can write a fantasy that takes place in a jungle. Or in a desert. Or in a prairie. The people can be extremely diverse in one region and less diverse in another. The cultures should differ. Different voices should be heard. Queer people exist. People of color exist. Not everyone has two arms or two legs or the ability to hear.

As for the fantasy elements, you also make up the rules. Don’t go searching around about how a certain magic spell is done, just make it up. Magic can be whatever color you want. It can be no color at all. You can use as much or as little magic as you want.

Keep track of what you put into your world and stick to the rules. There should be limits, laws, cultures, climates, disputes, and everything else that exists in our world. However, you don’t have to go over every subject when writing your story.

World Building:

Fantasy World Building Questionnaire

Magical World Builder’s Guide

Creating Fantasy and Science Fiction Worlds

Creating Religions

Quick and Dirty World Building

World Building Links

Fantasy World Building Questions

The Seed of Government (2)

Guide to Science Fiction and Fantasy

Fantasy Worlds and Race

Water Geography

Alternate Medieval Fantasy Story

Writing Magic

Types of Magic

When Magic Goes Wrong

Magic-Like Psychic Abilities

Science and Magic

Creative Uses of Magic

Thoughts on Creating Magic Systems

Defining the Sources, Effects, and Costs of Magic

World Building Basics

Mythology Master Post

Fantasy Religions

Setting the Fantastic in the Everyday World

Making Histories

Matching Your Money to Your World

Building a Better Beast

A Man in Beast’s Clothing

Creating and Using Fictional Languages

Creating a Language

Creating Fictional Holidays

Creating Holidays

Weather and World Building 101

Describing Fantastic Creatures

Medieval Technology

Music For Your Fantasy World

A heterogeneous World

Articles on World Building

Cliches:

Grand List of Fantasy Cliches (most of this can be debated)

Fantasy Cliches Discussion

Ten Fantasy Cliches That Should Be Put to Rest

Seven Fantasy Cliches That Need to Disappear

Avoiding Fantasy Cliches 101

Avoiding Fantasy Cliches

Fantasy Cliches

Fantasy Cliche Meter: The Bad Guys

Fantasy Novelist’s Exam

Mary Sue Race Test

Note: Species (like elves and dwarves) are not cliches. The way they are executed are cliches.

CHARACTERS

Seguir leyendo

65K notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Crime

Anonymous asked: I’m doing crime fiction in school and have to write a short story, but I’ve never written crime before and I don’t really know how. Do you have any tips? Maybe something on writing action scenes, creating suspense, and leaving clues? Thanks for any help you can give me!

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Save

Offensive Mistakes Well-Intentioned Writers Make

28K notes

·

View notes

Text

*dying* hope this help me

Easy Ways to Pick up the Sagging Middle of Your Novel

A lot of writers have trouble writing the middle of the novel. Either they don’t know how to structure it properly or they’ve just lost motivation (I’ve written endless posts on motivation, so try searching for them). I think we’ve all read books that have just lost all momentum in the middle, so here are a few ways to stop that from happening to your novel:

Try to lead to something important – The middle is a great time for a really exciting moment or the climax. There can be more than one, so don’t think you’re going to waste any momentum you have.

Throw in a twist – Blow your readers minds! Is there a moment you’ve been waiting to reveal to your audience? Do it in the middle of your novel and then deal with the aftermath.

Divide it into another three acts – Try to break down the middle of your novel into smaller pieces. Think of it as a beginning, middle, and end. Create a structure to follow.

Introduce some new blood – Focus on a new character. Introduce a new character. There should be a reason for them, so don’t go completely wild, but get excited about your new addition. Weave it into the plot.

Do something drastic – Do something unexpected to your hero. Throw a wrench in their plans. There should be ups and downs in your novel, so fit some in here.

Build an intense action sequence – Sometimes an intense scene breaks writers out of their doldrums. If it fits in your story, try it. Pump up the adrenaline.

Plan, plan, plan – For me, planning is the best way to figure out where my novel is going. Take a moment to think about what’s happening in your story and find a way to organize it.

Focus on tension – Build tension and put your readers on the edge of their seat. If there’s something exciting happening in your third act, now’s the time to build it up.

Think about the ending – If you’re unsure about the middle of your novel, take a look at the other parts. How are you going to get to your ending? Focus on that journey.

Make it less complicated – Sometimes middles are hard to write because they’re too complicated. Cut subplots that you can’t follow or just muddle up your story.

Obviously, trying all of these will make an absolute mess of your story, so pick and choose what might work for you. These are just suggestions and they won’t work for everyone’s story. Think of them as ideas to get your creative juices flowing.

And remember, the most important ideas to pursue are those that help drive the story forward or help reveal information about your characters!

-Kris Noel

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

FUCKING SAVING THIS

Writing Characters that Slowly Descend Into Madness

Okay y'all this is one of my absolute favorite tropes / character arcs / whatever you want to call it. I’ve written at least two characters that end up twisted and deranged… While it’s fun to do, it can be a little difficult to nail down, so I thought I’d share some tips!

From Avatar the Last Airbender’s Azula to Gollum, characters often think that they can handle the Ultimate Power™ when they really can’t. These corrupted characters and their character arcs can be tricky to write, so here’s some pointers!

The character to be corrupted should have a one track mind. Your character needs to have a goal in mind, one that (at least in their eyes) requires the Ultimate Power™. This goal can be as simple as world domination, or as complex as “I need to get revenge on this specific person in this specific manner, or else I won’t be satisfied.” It’s up to you, but you need to make sure that your character’s every action revolves around this central goal. Or, if your character has two motivations, like reconciling themselves to their family while simultaneously saving the world, make sure they can only do one of them! This will cause lots of conflict and it will be great..

Get used to writing internal conflict. In one of my novels, the main character has the power to clean the world’s water supplies, but her friends disapprove for…complicated reasons. She has something of a mental breakdown, wondering if she should be doing what she is. Internal conflict is a great way to show your character being pulled in two different directions; after all, tearing our characters apart is the name of the game.

Make sure your character thinks that they are using their Ultimate Power for good. Even if they’re not. Especially if they’re not. When you can follow a villain’s logic and understand why they are doing the horrific things they are, they become that much creepier.

The Ultimate Power must be so attractive that your character can’t help but use it. The only way your character can be corrupted by power is if they use this power. Therefore, they must use it often. Whether this be a superpower, power that comes from the crown on their head, or dark magic, make sure your reader gets plentiful helpings of seeing the character use it.

Don’t be afraid to take it slow. Characters descend into madness, they don’t plummet into it. Let your character spiral slowly downwards, let them saunter casually into their twisted ways of thinking.

If they can’t be redeemed, they should probably die. Characters that have gone power mad really only have two options: redemption or death. Sometimes your character can pull out of their downward spiral and recognize their mistakes. This may lead to them siding with the very people they had been against, like Magneto teaming up with Prof X to fight a Bigger Baddie. Or they could just admit their mistakes and go on their way, like Mystique occasionally does. But if you can’t find a way to redeem your character (or don’t want to), then you should probably consider killing them off. Characters mad with Ultimate Power™ are usually unsustainable, and will usually self destruct at some point.

A character who descends into their madness and power-craziness and has a descent that is really well written can be super engaging. They are, at least, my personal favorite to write and read about. Have fun, and happy writing!

If there’s a writing thing you want to see me post about or you just wanna say hi, go ahead! I’d love to hear from you.

4K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nice

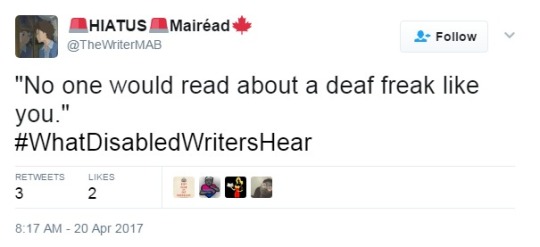

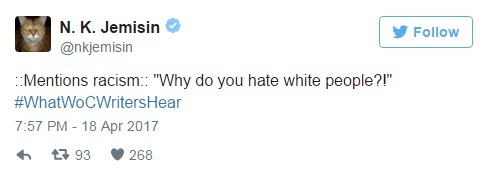

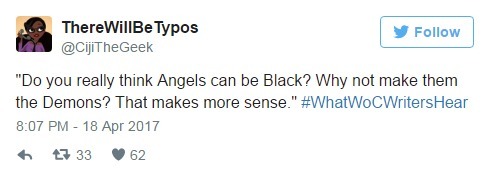

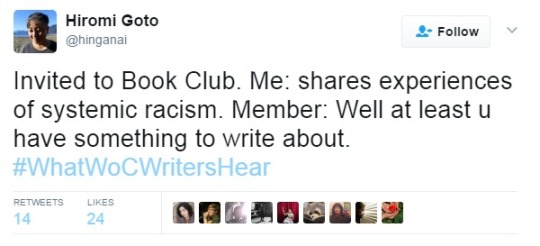

Thing only women writers hear, What Women of Colour Writers Hear & What Disabled Writers Hear

42K notes

·

View notes

Text

Saving

Problems That Make Me Close a Book:

1. A character looking into the mirror on the first page so that the author can tell me the reader what that character looks like physically. This just doesn’t matter to me and makes me suspect that the rest of the story won’t be what I’m interested in, either.

2. Starting with a battle scene or some other action scene in order to make me as a reader immediately engaged in action. I’m not going to care about characters dying if I’ve never met them before and I AM going to feel manipulated. Not a good look for a writer.

3. Telling everything in narrative rather than in scenes. This is less a problem about backstory than it is about letting me make my own judgments about events. Narrative means the author is making judgments. Scenes means I get to make those judgments.

4. Story cliches that aren’t changed in some meaningful way (despite what they say about Joseph Campbell, you can’t tell me the same hero story without some significant changes and keep me on board). I’ve read a lot and if you don’t surprise me, I’d probably rather just go back and read some of my old favorites instead.

5. Characters who act in what feel to me like stereotypical gendered ways. I don’t know people who act like this, so they don’t feel real to me.

6. Offensive racial stereotypes. I know it will sound to some like I’m just acting very politically correctly. The truth is, this hasn’t always bothered me. It’s started now that I’ve expanded my reading to include writers of color, and going back to some older writers is painful. Newer writers doing the same thing, well, I have little sympathy.

7. Stories with a lesson. This is often a problem in writers who want to write for children, but it happens in adult fiction, as well. Guess what? I don’t read books to learn lessons. Not even non-fiction. I may want information, but that’s not the same thing.

8. Books that feel like TV shows/movies I’ve already seen a thousand versions of.

9. Characters whose inner thoughts are boring and unintelligent.

10. Stupid worldbuilding, where there are obvious mistakes in science that even I, as a nonscientist can see. Or where the economy isn’t explained. Or where history is just too simple.

I’m not every reader and I’m not an editor, but I suspect that I’m not the only one who uses a list similar to this one.

487 notes

·

View notes

Text

IF YOU EVER NEED SOMETHING TO READ READ THIS

OK ARE YOU EVER IN NEED OF BOOK RECOMMENDATIONS BUT DON’T KNOW WHAT TO READ NEXT?

I present to you, straight from the internet, whichbook:

Here’s how it works: You click the link, and choose four categories and the extent to which these categories matter:

Then click “go” and it’ll come up with a number of books you might like.

DON’T LIKE THE CATEGORIES? NO PROBLEM - see this little thing:

THIS LITTLE THING WILL TAKE YOU TO THIS SLIGHTLY LARGER THING WHERE YOU CAN CHOOSE A BOOK BASED ON THE FOLLOWING:

YOU NOW HAVE NO EXCUSE TO NOT BE READING SOMETHING BECAUSE WHATEVER YOU WANT THIS SITE WILL COME UP WITH IT.

… Apart from bisexual retired alien dudes. No books on that. Yet.

399K notes

·

View notes

Note

Saving this

is it okay to switch povs in a story or should we just stay in one pov? follow up question whats the best pov to write in?

Thank you so much for your question! This definitely has a lot to do with opinion,but I’ll give you my personal standard.

The Types of POVs

There are three popular (and five total) styles of Point-of-Viewin writing! That’s plenty of options foryour story, but there are pros and cons to each:

First-Person (I &We) – This POV is very popular in young adult fiction currently, althoughit is typically frowned upon in fanfiction. First-Person POV is written from the eyes of the protagonist, and isbeneficial to the simplicity of the story, as well as the likeability of the protagonist. (Personalopinion: Not my favorite, but it’s definitely a good option.)

First-PersonPeripheral – Same visible style as First Person, but written from theviewpoint of a non-protagonist character. An example is the Sherlock Holmes series, which are written fromWatson’s POV, but focus on the character of Sherlock. (Personalopinion: I don’t see it often, so I don’t really have an opinion. Kudos for trying something new, though!)

Second-Person (You)– For obvious reasons, this is not a popular writing style in mainstreamfiction, as it can seem confusing. Thereis a style of fanfiction (I’ve heard it called Reader POV or Imagine POV) thatwrites a story including the reader, “You”, as the protagonist. (Personalopinion: I do not prefer it and have only tried to write in it as an experiment.)

Third-Person Limited(He, She, It, & They) – Another prevalent form of writing is inthird-person, which is a bit removed from the story as it plays at watching thecharacters from a distance. In theLimited style, the writer engages an outer view of one character at a time,following them through scenes, and possibly peeking into their thoughts. (Personalopinion: This is my favorite writing style, and it can work as a middleground between the impersonal nature of third-person and the confinedfirst-person.)

Third-Person Omniscient – Similar to Third-Person Limited,but written from a birds-eye view: no one character is followed or favored, andthere are insights into all of the characters minds, pasts, and motives. An Omniscient narrator knows all the factsabout everything in the scene. For morecomplicated plots or worldbuilding situations, 3PO is your man. (Personalopinion: A bit cold and removed from the character’s feelings andrelatability, but a good storytelling tool.)

Choosing POVs

Point-of-View is an important part of storytelling as itdictates how the story gets told – whom the reader likes, dislikes,understands, and follows. When choosinga point-of-view, it’s important to keep in mind three things:

Location of theAction – for instance, if Sally is stealing a diamond and Jim is the lookout,the character to watch is probably Sally. Even if readers (or you, as the writer) like or identify with Jim more,his point-of-view is not as important to the plot, and therefore should beexcluded.

The Charisma-ContentRatio – if you’re writing a chapter with plenty of interesting content,this might be an opportunity to introduce the POV of a less-engaging character,Laidback John. However, if the activitiesgoing on in this scene/chapter are simpler or more dialogue-based, Wild Annieis more likely to keep the reader’s eyes open. Use POV as a tool. Hold yourreaders hostage with either a sparkling character or exciting content.

The Viewpoint – different POVs can put a scene in a much different light, especially when itcomes to one-on-one character interaction. For example: in a scene where Mary is grieving the loss of her brother,it might be more emotional to write from the eyes of her husband, Heathcliff,as he struggles to help Mary through this time. POV makes our friends and our enemies for us, so choose it wisely. Who do you want the reader to watch? Who do you want the reader to misunderstand? What is the right viewpoint for the moral ofthe story?

Personal note: I have a formula for my most recent writing, in which I keep a freshperspective with two alternating POVs – the main male and the main female. Alternating POVs, if done clearly andconfidently, can create tension and provide two or more different sides to astory. I love reading stories like this,too!

Switching POVs

Alternating Points-of-View can be healthy for your story,keeping you out of a rut and offering multiple personalities with whom thereader can identify. But this is adouble-edged sword – a change of POV can confuse readers or cause yourplotline/character arcs to become disjointed. There are ways to avoid this, however:

Make it a routine– if at all possible, keep POV-changing to a schedule (every chapter, every twochapters, every scene, etc.) so that readers eventually anticipate it. If you find that you only want to write thePOV of a certain character a handful of times, you might want to look into Third-Person Omniscient POV.

Develop POVs individually– in my stories, I tend to give the first three or four chapters to onecharacter before adding another into the rotation. Beginning the cycle too early can be seen asflighty or “cheating.”

Limit yourself –you should only need 1-3 POVs to write a well-rounded story. If you find yourself reaching for 4+ POVs inone story, I’d again redirect you to Third-PersonOmniscient. Even with this strategy,you may find that readers struggle to attach or relate to any individualcharacter as they’re, in TV talk, not getting enough screen time.

Be clear and concise– stick to one POV per scene/chapter and make it known within the first fewsentences. Use names frequently,especially in the presence of two same-sex characters, and use thoughts as wellas strong character voice in the narrative to help readers keep the POV intheir mind.

If you at any pointfind yourself typing the words “____’s POV”, anywhereat all, stop and look at yourself. If you have to clarify POV outside of the prose, you’ve made a mistake.

I hope this answered your question! Also, super sorry that this took me a whileto answer – finals have been kicking my butt, but I’m through the worstnow. Thanks for your patience :)

If you need advice on general writing or fanfiction, you should maybeask me!

257 notes

·

View notes

Text

Save

Wordbuilding: Government

“Government is a necessary evil,” President Reagan once said. And whether or not that’s the view of the people in your world or culture, there is usually some form of government to keep things in order. In this post, I’ve compiled a list of questions pertaining to government. It’s not exhaustive, but it can help you get started on creating your culture’s governmental system. Get creative, get detailed, and go outside of the questions listed. But also hve fun.

The questions compiled are inspired, taken, modified, or edited from three forums on the NaNoWriMo website: Respond, Answer, Ask 2016 Worldbuilding, Respond, Answer, Ask, 2016 Fantasy, and Fantasy Worldbuilding Questions.

Who leads the country? A president? A king? An emperor? A chief? Or something that the English language does not have a word for?

What are the other forms of authority? Is there a second in command? A princess? Vice president? Senator? Chancellor?

What are the ranks of nobility?

How much power does each rank have? Are some ranks just titles? Do some ranks strike fear into the hearts of the commoner?

How did these ranks come to be in the first place?

How does one attain these ranks?

How is succession determined in the nation? Does it go to the next person in line? Do people vote? Does the king or queen choose the next ruler? Are people nominated and have to face each other in a succession of challenges? Is there a long complicated process?

What kind of government is in place?

Do people vote or do only the rich vote among themselves to determine who will become the next leader? Can anyone walk into the voting area? Are people expected to own land before they can vote? Is there a fee to pay to vote? What are some rules when it comes to voting?

What do the citizens think of their leadership?

What qualities do the people respect in a leader? What qualities do they disdain?

What sort of civic duties is the average citizen responsible for? Voting? Jury service? Military service? Temple service?

What would it take to completely change the balance of power?

How does the authority settle disputes to avoid wars?

What sort of public services are available?

Does government provide public roads, hospitals, and other public services?

Does government control orphanages, homeless shelters, and the such?

Do tiny, far flung villages know anything about who’s in charge, beyond maybe his/her name? Does it matter to them? Do they hear the title of “king” or “president” and just laugh? Do they even know the ruler’s name?

What is the state of foreign relations?

How are treaties and agreements made between sovereign powers?

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

GUARDANDO

How to Write Characters That Are Complex

So this was an ask I received from @costangeles, and I thought that it deserved one of my Long Posts™ to properly answer it.

Complex characters are super, super important to any fictional work, whether it be an OC in your personal short story/novel/etc. or an OC in a fanfiction. If the characters in your work aren’t complex, the readers won’t care much about the characters and therefore won’t care much about the story itself.

Complex characters aren’t a suggestion, they are a necessity if you want your story to be successful and well-liked by your readers.

Since they’re so important, I decided to make a post on how to write them instead of just answering it on the ask.

1. Know the definition of a complex character

People take a look at the phrase “complex character” and think, “Oh, I know what that is! It’s a character that’s complex!”

They are right, in a sense, but there is so much more to complex characters than it states in the name.

According to this document (which comes up when you Google “complex character”)

“A Complex character, also known as a Dynamic character or a Round character displays the following characteristics:

1. He or she undergoes an important change as the plot unfolds.

2. The changes he or she experiences occur because of his or her actions or experiences in the story.

3. Changes in the character may be good or bad.

4. The character is highly developed and complex, meaning they have a variety of traits and different sides to their personality.

5. Some of their character traits may create conflict in the character.

6. He or she displays strengths, weaknesses, and a full range of emotions.

7. He or she has significant interactions with other characters.

8. He or she advances the plot or develops a major theme in the text.”

Now that you know the definition of a complex character, it’ll probably be easier to write them. Technically, I could just end it here and have the document give you all the tips, but I felt like I should elaborate on the few of the points just to emphasize how important they are.

2. Your Character’s Gotta Change

Your story/novel/fanfiction is outlining a gigantic event, right? One that’s harrowing and draining and tough on the body and the mind?

Just a note: ANY NORMAL HUMAN BEING WOULD CHANGE AFTER EVENTS SUCH AS THESE.

It’s not feasible for a character NOT to change after something like this happens.

I’m going to use my book as an example:

Andrew, the main character and the narrator of the story, is an angel stuck in Hell.

Do you know what happens in Hell? Demons torture people.

Do you know what happens to Andrew? He gets tortured.

Now, who wouldn’t change in this environment? Andrew had to adapt in order to endure the least amount of suffering as possible. At the beginning of the story, he is quiet and reserved, and easily spooked. Wary of new people.

But as the plot progresses and he’s rescued by the other characters in the story, he comes out of his shell and realizes that there’s no one to fear.

Your characters have to change like that. They may not have to go through literal hell, but they sure have to change after the event happens.

Some of you might be panicking right now because you don’t want to change your character, or can’t see a way that your character can change.

Don’t worry, I’ve made a list of traits that can be changed during the course of your story. All of these things can either go up or down as the plot progresses.

-Ambition

-Apathy

-Assertiveness

-Capability

-Compassion

-Confidence

-Consideration

-Courage

-Cowardice

-Dependability

-Determination

-Generosity

-Honesty

-Ignorance

-Impulsiveness

-Individuality

-Independence

-Insecurity

-Literally any bad trait

-Protectiveness

-Spirituality

-Tolerance

-And many more

3. They Gotta Have a Personality

This one is necessary for any character, but like with the phrase “complex character”, many people just put it into generic terms.

Think of any character from any book, movie, TV show, etc.

Now, think about their personality traits.

Notice how, if they’re a good, well-developed character, they have a lot of them.

A personality doesn’t just mean “Oh, I like pizza”.

Liking something unimportant doesn’t make a person who they are.

Liking something is not a personality trait unless that thing is super important to them like sports or school or their family. (Athletic, bookish, family-oriented)

People are incredibly complex creatures that have a whole fuckton of things that are good and bad about them. You can’t just go online to one of those “character traits” charts and pick and choose like five of them. Your character should have a whole load of traits, otherwise they’re not a complex character.

Traits should be diverse. There should be both good and bad traits. Major and minor traits.

Take a moment and write down all of your character’s traits. They can’t be physical traits, and they can’t be minor things that they only “like” and can live without.

If there aren’t a lot of them or you can’t think of that many, then your character is not complex.

This is okay for side characters, but for your main protagonist it’s a big no-no.

4. Your character has to be an active participant in the plot

THIS IS SUPER IMPORTANT STAR THIS, HIGHLIGHT IT, UNDERLINE 100 TIMES

Here is the big question: Is your character moving the plot, or is the plot just happening to your character?

If you answered the latter, then you have a big problem.

I’m not even going to sugarcoat it; if your protagonist, the one you love with all of your heart and couldn’t bear to live without, is not advancing the plot, then they shouldn’t exist in the story.

Your character’s choices have to make the plot move forward. Their choices have to impact the story an cause consequences, whether they be good or bad in the long run for the whole cast of characters.

Unless your character is forced to be a passenger (whether it’s because of lack of physical/mental/magical ability compared to the supporting cast, or because they are actually forced), they should be the one in the driver;’s seat, not the one that was dragged along for the ride.

If you still can’t grasp what I’m talking about, you should watch this video, which explains it perfectly.

HOPE THIS HELPED!

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

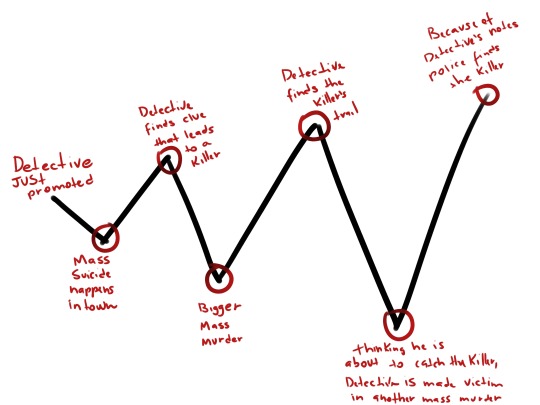

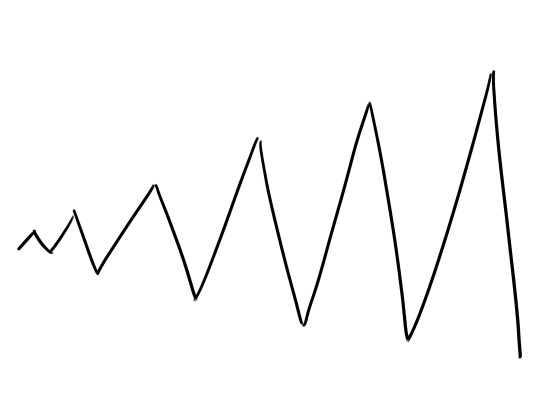

Creating plots with the zigzag method

I’ve learned this method years ago and I’ve been using it ever since. The zigzag plot creator starts like this:

An crescent zigzag.

You can have as many up and downs as you want. I’ve drawn six to keep it simple. Alright, this zigzag is your storyline and every corner is an important event that will change everything:

Every down represents a bad thing happening to your main characters, taking them further away from their goal. Every up is a good event, taking them closer to their goal:

So, when the zigzag goes down, something bad must happen. When the zigzag goes up, something good must happen. The reason why we drew a crescent zigzag is because every down must be worse than the previous, and every up must be better than the previous. As the zigzag advances, events become more serious and relevant.

Let’s apply the zigzag method. My storyline is a detective trying to catch a serial killer in a futuristic city. Minutes later, this is what I’ve got:

Start: Detective, our protagonist, is just promoted

Down #1: Mass suicide happens in town, detective gets the case, the whole town thinks it might have been a religious suicide act, but detective suspects that someone single-handed killed all those people

Up #1: Detective finds clue about a possible killer

Down #2: A bigger mass murder happens, a true massacre, it’s a definitely a murder

Up #2: Detective finds the killer’s trail

Down #3: Thinking he is ahead of time, close to catching the killer, detective ends up dead in another mass murder

Up #3: Because of his notes and discoveries, the police is able to find the killer before they leave town

From this point on you can play with zigzag as much as you want. For example, changing the orientation of the zigzag for a bad ending:

Lots of ups and downs:

Or just a few:

It’s up to you (see what I did there?).

You can plot any type of story with the zigzag method. It’s a visual and easy process for a very complex task.

20K notes

·

View notes

Link

Have you ever read a book or seen a movie that had such great characters that even now, months or years later, you still think about them?

That’s the real magic of storytelling. Being able to write a character that sticks in someone’s heart and mind all their life is incredibly exciting. Of course, what exactly sticks in a character for one person may be different for someone else.

But there are a few trends. If you study memorable characters that have endured over time, you’ll find that certain traits show up again and again. This article contains 7 traits in particular that can help your characters carve a spot in the minds of readers (although there may be more than these 7!).

Before we get into the good stuff, let me start this off with two caveats.

First: don’t make all of your characters all seven of these traits. In MOST cases, that’s just bad writing (but there are always exceptions). Pick one, maybe two. Or none. Or bits and pieces of several! None of the things listed are set-in-stone the only way to have an enduring character. They’re just guidelines.

Second: don’t assume that giving your characters one or two of these traits will instantly make them a great, well-rounded character. It’s not that easy. Strong characters have a lot of complexity and need a lot more depth than what I can explain in just one list.

And with those warnings, I give you 7 Traits of Enduring Characters. I got this information at a writing conference and I’m excited to pass on what I’ve learned.

1. An air of mystery.

There’s something about this character that we don’t fully know. If your character has a dark past, it’s usually best to keep most of it in the dark—at least for the first half of the book. Don’t tell us everything upfront. Make us wonder.

Example: Think of Strider (Aragorn) from The Lord of the Rings, the first time we meet him. He’s dark and mysterious and up to something. We don’t even know if he’s good or bad yet. Aragorn ends up fitting some of these other traits too, but right off the bat, this is the first one we see.

2. Worthy of redemption.

This can apply to anti-heroes, villains, or anyone else applicable in your story. They’re a big jerk, but a tiny spark of humanity can sometimes help bring them to life. Maybe they’ve got a soft spot for someone or something, or maybe they truly believe they’re doing what they’re doing for the greater good. It can even make your villains scarier, because it makes them harder to pin as nothing but an evil monster—it’s not black and white like that. The real villains aren’t always so obvious.

Example: This can become a really gray area of morality, since some characters do things so awful that some readers will NEVER forgive them, regardless of their redemption arc. But a character like Loki in Marvel’s Thor movies is a good example. His bitterness causes him to lash out and do awful things, but Thor still believes his brother is capable of redemption. He still sees the good in a family member who he loves so much.

3. Highly loyal, or highly treacherous.

Either you know you can trust them, or you know you can’t. Obviously you can’t give this trait to all of your characters. And actually, it’s not as predictable as you might think. Just because we can’t trust someone doesn’t mean we know what they’re up to. We’ll be anticipating their move but completely unaware of what they’re planning—which is actually a great place to build tension. As far as highly loyal, sometimes it’s nice to have that one character that is a “safe spot” for your character. You need to take breaks from the tension every now and then!

Example: Back to Lord of the Rings, we have Sam, who is infinitely loyal to Frodo. When Frodo is trying to leave the Fellowship and go on his own, Sam follows Frodo’s boat into the water even though he can’t swim and almost drowns as a result. When the end is near and both are completely spent, Sam finds the strength to carry Frodo partway up the mountain. This incredible, selfless loyalty and friendship endears Sam to viewers.

Example: Queen Levana from the Lunar Chronicles fits the opposite side of the spectrum as someone highly treacherous. She is loyal to absolutely no one and will lie, manipulate, and mislead to get what she wants. She claims loyalty and faithfulness to her kingdom, but knowingly imposes harsh living conditions on the vast majority of her kingdom. She claims loyalty to the man she’s in love with, but manipulates him just as much as everyone else and twists the promises she made him to her own benefit.

4. Consistent, but capable of surprises.

People are usually pretty consistent based on their personality traits. They tend to make choices based on their core values, which can vary a little, but for the most part they stay on the same route. At the same time, they’re not flat—they’re capable of making an unexpected choice

Example: Since we’re talking about Lord of the Rings so much… how about Merry and Pippin? They’re consistent in their role of comic relief, and in the earlier movies, they’re not capable of much (they don’t have special skills or combat training). Despite this, they show themselves to be quick-witted and brave when the time calls for it and they pull of incredible, unexpected feats.

5. Highly self-sacrificing.

These characters accept the challenge. When no one else will volunteer, they step up. When it comes to the life of someone they care about, they’re willing to risk their own welfare. This can make for an interesting read when we know they’ll give 100% when things get rough—even die if they have to.

Example: One of the most obvious examples here is Katniss from The Hunger Games. She speaks up and volunteers for almost certain death to save her sister’s life. This sort of knee-jerk reaction that she had to speak up is one of the first impressions we get of her, as readers.

6. Part of a love story.

This doesn’t have to be a romantic love story—just any powerful relationship. The lengths your character will go through for their friend/lover/family member/etc can make them more enduring as a character, because of the worth in their relationship.

Examples: Romeo and Juliet; Katniss and Prim; or even Harry, Hermione, and Ron. Really, it’s more about the relationship and the lengths one will go to save/protect the other.

7. Succeed at the impossible.

They are an expert of their task—they can do things most couldn’t dream of accomplishing. Sometimes there’s a little bit of wish-fulfillment in a character meeting this trait, which is why you can’t have it in every member of your cast. Occasionally, however, it’s nice to have someone who’s really good at what they do.

Example: This describes a TON of main characters, especially in the fantasy and sci-fi genres. Think about Luke Skywalker, Katniss Everdeen, Frodo Baggins, Furiosa, Celaena Sardothian… the list goes on. Anyone who’s overthrown an empire/government, anyone who saved the world from certain doom. You’ll also notice that many of these characters are an expert at a certain task or skill. When they’re in their element, we have someone we can root for because we’re confident in their ability to come out on top.

A lot of iconic characters possess 2-5 of these traits, so remember—you’re not limited to one, and you don’t have to squeeze in all 7.

Do you think there are any other traits that you see in memorable characters that should be included in a list like this? Which traits do you see in your own main characters?

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

HELL YES!

I wonder if, in superhero universes, the villains ever get contacted by those “Make a Wish Foundation” and similar people.

I mean, the heroes do, of course they do, kids who want to meet Spiderman or Superman or get to be carried by the Flash as he runs through Central City for just thirty seconds.

But surely there are also the kids, who - because they are kids and sometimes kids are just weird - decide that what they really, really want is to meet a supervillain. Because he’s scary or she’s awesome or that freeze ray is just really, really cool, you know?

227K notes

·

View notes

Photo

The reason why I´m here....

La razón por la cual estoy aqui...

0 notes