Just a gal rereading Lord of the RIngs, having many thoughts and several feelings.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

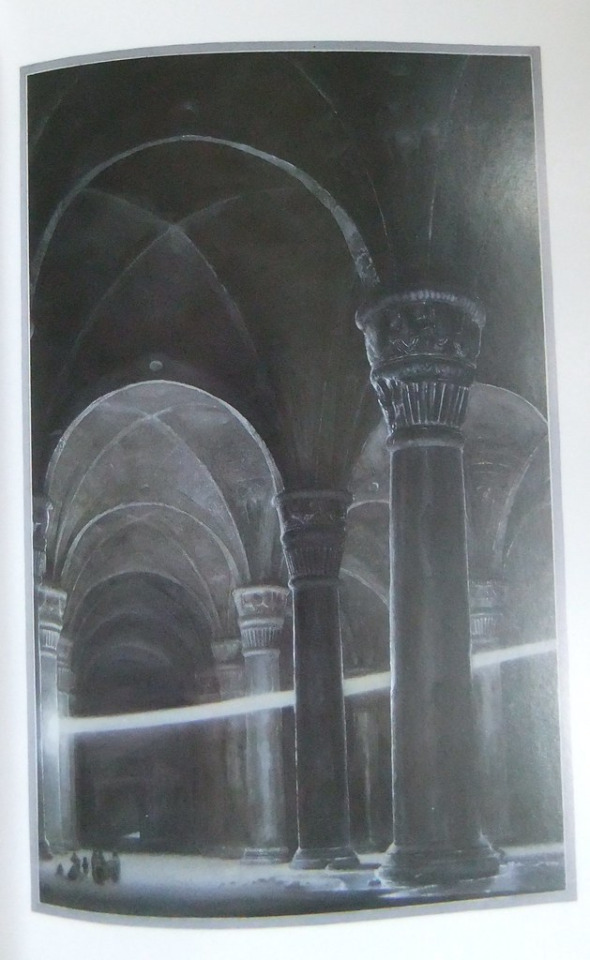

I just ran across a bunch of pretty Bakshi Lord of the Rings concept art by Tom Lay. I don’t think I’ve ever seen these before. It looks like: The Misty Mountains, Isengard, Moria, and the Shire

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

it’s just hard not to think about the fact that in 1915, JRR Tolkien went to war not with but certainly in the same army and many of the same battles as his 3 best school friends, all nicely upper class young men who had never known much loss, and only he and one other came back alive - and a couple decades later, he wrote a book in which 3 nicely upper class young men (and one very excellent gardener) who have never known much loss go to war together, or at least they start out together, and they all come home alive. (Though one cannot bear it, and does not stay.)

123K notes

·

View notes

Text

‘And he died with the Dawn in his eyes’

On the eve of war, Tolkien encounters ‘Earendel’

Exeter College, Oxford, 1914.

Note: By the end of 1914, most of Tolkien’s Oxford friends and fellow TCBS members had enlisted. But as an orphan who had always struggled to stay out of poverty, and being by then engaged to his beloved Edith, Tolkien could not afford to abandon his studies, which were crucial to his future chances of an academic career. And so, despite immense pressure from his extended relations and intense societal scorn, he deferred his enlistment until after finishing his final exams the following summer.

“ Back before war broke out, at the end of the university term, Tolkien had borrowed from the college library Grein and Wülcker’s Bibliotek der angelsächsischen Poesie. This massive work was one of those monuments of German scholarship that had shaped the study of Old English, and it meant Tolkien had the core poetic corpus at hand throughout the long summer vacation. He waded through Crist, by the eighth-century Anglo-Saxon poet Cynewulf, but found it ‘a lamentable bore’, as he wrote later: ‘lamentable, because it is a matter for tears that a man (or men) with talent in word-spinning, who must have heard (or read) so much that is now lost, should spend their time composing such uninspired stuff.’ Boredom could have a paradoxical effect on Tolkien: it set his imagination roaming. Furthermore, the thought of stories lost beyond recall always tantalized him. In the midst of Cynewulf’s pious homily, he encountered the words ‘Eala Earendel! engla beorhtast / ofer middangeard monnum sended, ‘Hail Earendel, brightest of angels, above the middle-earth, sent unto men!’ The name Earendel (or Éarendel) struck him in an extraordinary way. Tolkien later expressed his own reaction […]: ‘ I felt a curious thrill, as if something had stirred in me, half wakened from sleep. There was something very remote and strange and beautiful behind those words, if I could grasp it, far beyond ancient English….I don’t think it any irreverence to say that it might derive its curiously moving quality from some older world.’ But whose name was Éarendel? The question sparked a lifelong answer.

Cynewulf’s lines were about an angelic messenger or herald of Christ. The dictionary suggested it meant ray of light, or the illumination of dawn. Tolkien felt that it must be a survival from before Anglo-Saxon, even from before Christianity. (Cognate names such as Aurvandil and Orendil in other ancient records bear this out. According to the rules of comparative philology, they probably descended from a single name before Germanic split into its offspring languages. But the literal and metaphorical meanings of this name are obscure.) Drawing on the dictionary definitions and Cynwulf’s reference to Éarendel as being above our world, Tolkien was inspired with the idea that Éarendel could be none other than the steersman of Venus, the planet that presages the dawn. At Phoenix Farm [his widowed aunt’s residence in Nottinghamshire], on 24 September 1914, he began, with startling éclat:

Éarendel sprang up from the Ocean’s cup In the gloom of the mid-world’s rim; From the door of Night as a ray of light Leapt over the twilight brim, And launching his bark like a silver spark From the golden-fading sand; Down the sunlit breath of Day’s fiery Death He sped from Westerland.

Tolkien embellished ‘The Voyage of Éarendel the Evening Star’ with a favourite phrase from Beowulf, Ofer ýpa ful, ‘over the cup of the ocean’, ‘over the ocean’s goblet’. A further characteristic of Éarendel may have been suggested to Tolkien by the similarity of his name to the Old English ēar ‘sea’: though his element is the sky, he is a mariner. But these were mere beginnings. He sketched out a character and a cosmology in forty-eight lines of verse that are by turn sublime, vivacious, and sombre. All the heavenly bodies are ships that sail daily through the gates at the East and the West. The action is simple: Éarendel launches his vessel from the sunset Westerland at the world’s rim, skitters past the stars sailing their fixed courses, and escapes the hunting Moon, but dies in the light of the rising Sun.

And Éarendel fled from that Shipman dread Beyond the dark earth’s pale. Back under the rim of the Ocean dim, And behind the world set sail; And he heard the mirth of the folk of earth And hearkened to their tears, As the world dropped back in a cloudy wrack On its journey down the years.

Then he glimmering passed to the starless vast As an isléd lamp at sea, And beyond the ken of mortal men Set his lonely errantry, Tracking the Sun in his galleon And voyaging the skies Till his splendor was shorn by the birth of Morn And he died with the Dawn in his eyes.

It is the kind of myth an ancient people might make to explain celestial phenomena. Tolkien gave the title in Old English too (Scipfæreld Earendeles Æfensteorran), as if the whole poem were a translation. He was imagining the story Cynewulf might have heard, as if a rival Anglo-Saxon poet had troubled to record it.

As he wrote, French and German armies clashed fiercely in the town of Albert, in the region named for the River Somme, which flows through it. But Éarendel’s is a solitary species of daring, driven by an unexplained desire. He is not (as in Cynewulf) monnum sended, ‘sent unto men’ as a messenger or herald; nor is he a warrior. If [this early version of] Éarendel embodies heroism at all, it is the maverick, elemental heroism of individuals such as Sir Ernest Shackleton, who that summer had sailed off on his voyage to traverse the Antarctic continent.

If the shadow of war touches Tolkien’s poem at all, it is in a very oblique way. Though he flies from the mundane world, he listens to its weeping, and while his ship speeds off on its own wayward course, the fixed stars take their appointed places on ‘the gathering tide of darkness’. It is impossible to say whether Tolkien meant this to equate in any way with his own situation at the time of writing; but it is interesting that, while he was under intense pressure to fight for King and Country, and while others were burnishing their martial couplets, he eulogized a ‘wandering spirit’ at odds with the majority course, a fugitive in a lonely pursuit of some elusive ideal.

What is this ideal? Disregarding the later development of his story, we know little more about the Éarendel of this poem than we do the stick figure stepping into space in Tolkien’s drawing The End of the World. Still less do we know what Éarendel is thinking, despite his evident daring, eccentricity, and uncontainable curiosity. We might almost conclude that this is truly ‘an endless quest’ not just without conclusion, but without purpose. If Tolkien had wanted to analyze the heart and mind of his mariner, he might have instead turned to the great Old English meditations on exile, The Wanderer and The Seafarer. Instead he turned to Romance, the quest’s native mode, in which motivation is either self-evident (love, ambition, greed) or supernatural. Éarendel’s motivation is both: after all, he is both a man and a celestial object. Supernaturally, this is an astronomy myth explaining planetary motions, but on a human scale it is also a paean to imagination. ‘His heart afire with bright desire’, Éarendel is like Francis Thompson (in Tolkien’s Stapeldon Society paper), filled with ‘a burning enthusiasm for the ethereally fair’. It is tempting to see analogies with Tolkien the writer bursting into creativity. The mariner’s quest is that of the Romantic individual who has ‘too much imagination’, who is not content with the Enlightenment project of examining the known world in ever greater detail. Éarendel overleaps all conventional barriers in a search for self-realization in the face of the natural sublime. In an unspoken religious sense, he seeks to see the face of God. ”

— John Garth, Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth

751 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Legend of Zelda Replica Shields made by BobsiesCosplay

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Some years ago, I was stuck on a crosstown bus in New York City during rush hour. Traffic was barely moving. The bus was filled with cold, tired people who were deeply irritated—with one another; with the rainy, sleety weather; with the world itself. Two men barked at each other about a shove that might or might not have been intentional. A pregnant woman got on, and nobody offered her a seat. Rage was in the air; no mercy would be found here.

But as the bus approached Seventh Avenue, the driver got on the intercom. “Folks,” he said, “I know you’ve had a rough day and you’re frustrated. I can’t do anything about the weather or traffic, but here’s what I can do. As each one of you gets off the bus, I will reach out my hand to you. As you walk by, drop your troubles into the palm of my hand, okay? Don’t take your problems home to your families tonight—just leave ‘em with me. My route goes right by the Hudson River, and when I drive by there later, I’ll open the window and throw your troubles in the water. Sound good?”

It was as if a spell had lifted. Everyone burst out laughing. Faces gleamed with surprised delight. People who’d been pretending for the past hour not to notice each other’s existence were suddenly grinning at each other like, is this guy serious?

Oh, he was serious.

At the next stop—just as promised—the driver reached out his hand, palm up, and waited. One by one, all the exiting commuters placed their hand just above his and mimed the gesture of dropping something into his palm. Some people laughed as they did this, some teared up—but everyone did it. The driver repeated the same lovely ritual at the next stop, too. And the next. All the way to the river.

We live in a hard world, my friends. Sometimes it’s extra difficult to be a human being. Sometimes you have a bad day. Sometimes you have a bad day that lasts for several years. You struggle and fail. You lose jobs, money, friends, faith, and love. You witness horrible events unfolding in the news, and you become fearful and withdrawn. There are times when everything seems cloaked in darkness. You long for the light but don’t know where to find it.

But what if you are the light? What if you’re the very agent of illumination that a dark situation begs for?

That’s what this bus driver taught me—that anyone can be the light, at any moment. This guy wasn’t some big power player. He wasn’t a spiritual leader. He wasn’t some media-savvy “influencer.” He was a bus driver—one of society’s most invisible workers. But he possessed real power, and he used it beautifully for our benefit.

When life feels especially grim, or when I feel particularly powerless in the face of the world’s troubles, I think of this man and ask myself, What can I do, right now, to be the light? Of course, I can’t personally end all wars, or solve global warming, or transform vexing people into entirely different creatures. I definitely can’t control traffic. But I do have some influence on everyone I brush up against, even if we never speak or learn each other’s name. How we behave matters because within human society everything is contagious—sadness and anger, yes, but also patience and generosity. Which means we all have more influence than we realize.

No matter who you are, or where you are, or how mundane or tough your situation may seem, I believe you can illuminate your world. In fact, I believe this is the only way the world will ever be illuminated—one bright act of grace at a time, all the way to the river.“

–Elizabeth Gilbert

77K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today is Hobbit Day! (Sep 22nd) the shared birthday of Bilbo & Frodo Baggins, so finished this morning is this sketch of Bag End, inspired by the countryside around me (and with bits of said countryside littering the photo, complete with all the tiny creatures I unwittingly brought in, and had to capture and put outside again), drawn in pastel pencils on toned paper 21x29cms

I may put this up on redbubble later today if there’s interest in prints.

647 notes

·

View notes

Text

ok but like when did self-sacrifice become synonymous with death? writers seem to have forgotten that people can make personal sacrifices for the greater good without giving their lives. plots about self-sacrifice and selflessness don’t always have to end in death. suffering doesn’t have to be mourning. you can create drama and emotional depth on your show without killing everyone. learn to explore the meaning of living rather than dying

180K notes

·

View notes

Text

if theres no found family what is the God Damn Fucking Point

93K notes

·

View notes

Photo

THAT THERE’S SOME GOOD IN THIS WORLD, MR. FRODO… AND IT’S WORTH FIGHTING FOR.

9K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Living amongst giants | Banff National Park | tvardi

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

A floor mosaic from the dining room of a Pompeii home. In Roman culture, the act of eating was often accompanied by reminders of mortality. Credit: Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

“The world is indeed full of peril, and in it there are many dark places; but still there is much that is fair, and though in all lands love is now mingled with grief, it grows perhaps the greater.”

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The reason Lord of the Rings’ special effects have held up so well and still look so gorgeous- especially in the backgrounds and environments– is because they weren’t **trying** to be realistic.

LOTR’s special effects are stylized in a very careful, deliberate, and beautiful way.

In a behind-the-scenes video, the films’ visual effects supervisor explained:

We wanted the look of the film to have this storybook look to it. This is one of the things that Peter Jackson would impress upon the post-grader. He would literally sit there with watercolor (paintings) and say: THIS is what I want it to look like.”

Compare Alan Lee’s watercolor painting (its texture, its limited and unreal color palette, and the careful use of bright highlights in specific places that “frame” the characters/create an interesting composition)–

To the very similar look of the final film:

Because the goal wasn’t to create a perfectly realistic version of Moria. It was to create a version of Moria that looked like a watercolor painting.

And this “watercolor painting” effect isn’t just epic fantasy moments either. Even many of the non-fantastical backgrounds in Lord of the Rings don’t look “fully realistic.” They look very high-contrast and painterly, with dramatic unreal shafts of light bursting through the clouds:

And again, this is by design:

“We wanted to nudge it sideways from reality. New Zealand is a lovely country but it’s still New Zealand, still a real country….and I wanted to nudge it slightly to Middle Earth, which is an ancient world….a world of myth, and legend.”

And the watercolor storybook-inspired colors and lighting isn’t just in the environments either. It was also used in very basic dialogue scenes, to make you really feel like the entire movie was taking place in a fantasy world:

Because the stylization in Lord of the Rings is so consistent– but not to so exaggerated that it gets distracting— it creates this beautifully unreal and dreamlike tone that is completely unlike any other movies I’ve ever seen.They really do end up feeling like “watercolor fairy tales” come to life.

47K notes

·

View notes