blatant yet accidental plagiarism spiralling into an unoriginal original novel idea

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

it’s a pomegranate tree by the way. always the fucking pomegranates. pomegranates as a metaphor for captivity after colonisation, as opposed to blessing and favour from the gods. jasmine says it’s a miracle that there’s a pomegranate tree in lashevsk in all places. she doesn’t see the irony - a blessed tree ripped from its native soil and used as a tombstone. they’re a pale imitation of true pomegranates, and the seeds are small and sour.

0 notes

Text

thinking about this, the idea is more about grief than morality and memory. you could argue that grief if both of those, but…

1. kesone’s grief for himself, for everyone that’ has been ripped away from him, for the future he could have had, the life he almost did

2. jasmine’s grief for her lover, and her culture, and her sense of identity

3. aleksander’s grief for people he considered family, for his culture, for jasmine, for kesone

4. cain’s grief for úna, for his daughter, for what violence has taken from him

5. delilah’s grief for her past, her childhood, parents she never knew

0 notes

Text

my sister helped me come up with the new name - for the greater good. she doesn’t know a lot about the plot but she knows aleksander’s entire character motivation - which is doing things for the greater good.

ironic, isn’t it? that a book centred around kesone and his story is just a reflection aleksander’s greatest ideal.

0 notes

Text

cain’s workshop as a physical manifestation of himself. dilapidated. abandoned. taken over by someone else. covered in vines, with darling little window boxes out front that can’t hold any flowers. his tools are in there. so his daughter’s room - and her music box, the one he designed, crafted, modelled after his wife. maybe the place is haunted. it wouldn’t be far from how he is.

0 notes

Text

sorry gamers i did not mean to repost leon on this blog but also… you gotta admit he’s cute as

0 notes

Text

LEON KENNEDY

sorry what

old sketches of my boyo

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

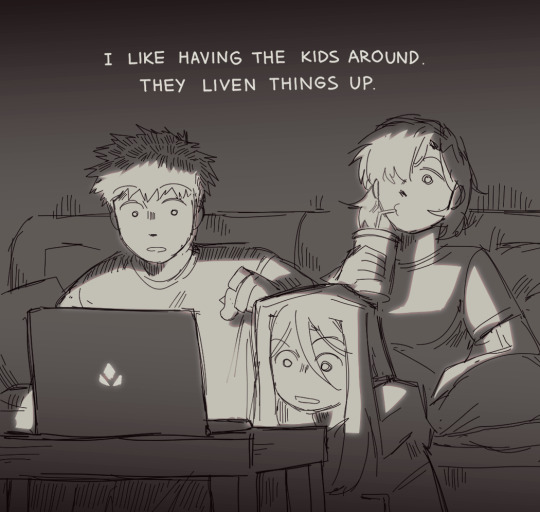

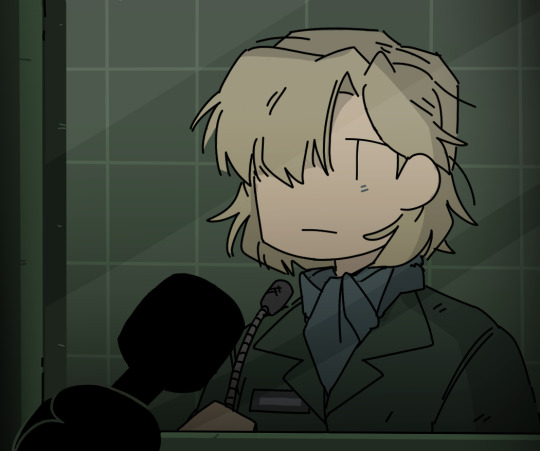

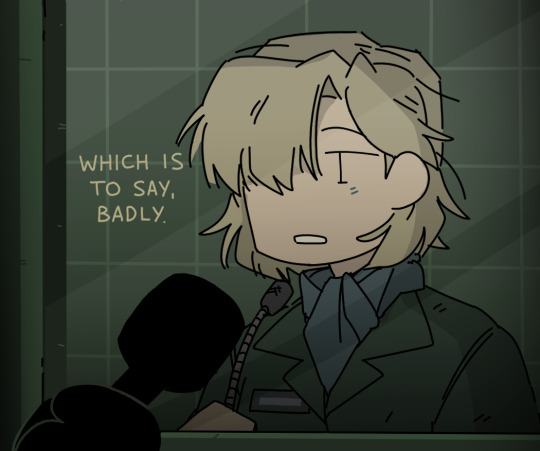

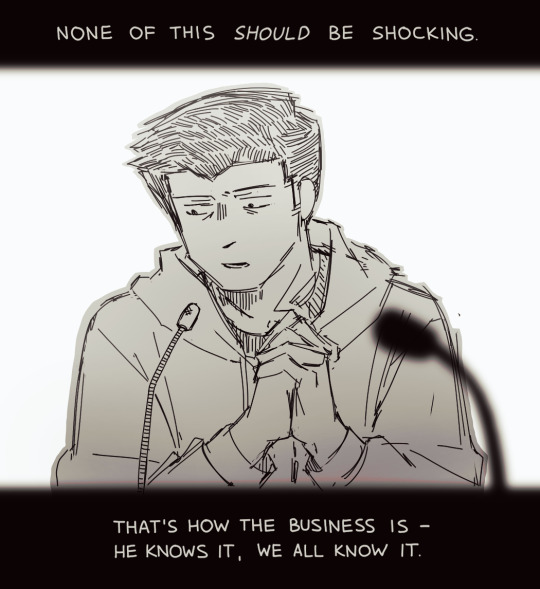

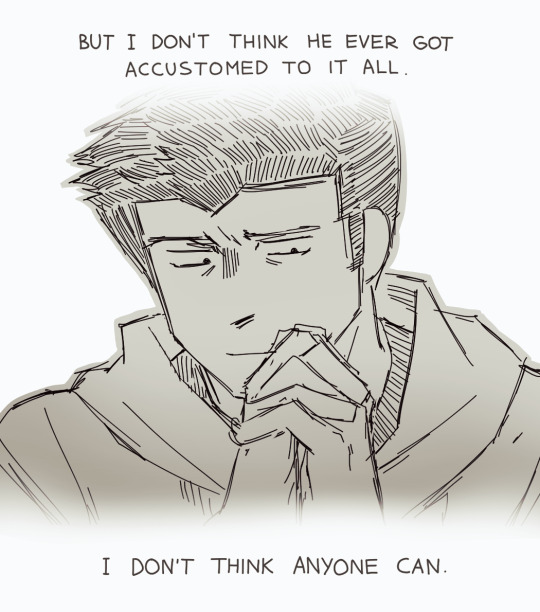

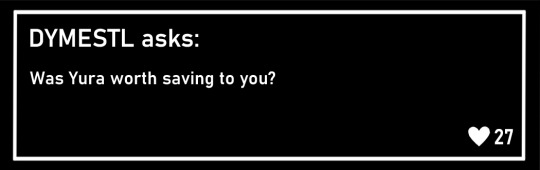

HOLY FUCK SERGEI

Q&A: Olga Orlova

Broadcasting straight from the swamp green quarters of the local women's prison, today we're asking Olga Orlova your most pressing questions. As usual, you can find the transcript of all the text at the bottom.

Let's get to it.

606 notes

·

View notes

Text

also adrian is now aleksander, for the reasons below:

1. ✨radiant✨ 🥰carefree🥰 😚dreamy😚 ADRIEN the fragrance

2. adrian is such a dislikeable name. it makes him so douchebag. he is NOT that much of a douchebag. he might be a little morally questionable but he isn’t a DICK

3. aleksander has better vibes - aleksander (the great) and i like the sound of it more; it also links better to him choosing a name that will help in fit in, and because the emperor and empress are russian-esque, he chose a name similar to theirs

4. the diminutive version of aleksander is sasha, which i think is quite cute, and aleksander doesn’t realise this and gets pissy whenever keo calls him by it because it means fiend or smt in his native language

(his original last name is Lualhati, meaning spiritual peace and is derived from Luwalhati in Tagalog, meaning glory. i had a first name for him and then i lost it… my bad (it’s probably amihan, as in northeast wind))

0 notes

Text

aleksander flips his hair and says sorry for being so cunty, all while kesone is holding the remains of his arm and wondering how he got here, and jasmine has deserted the army and joined a religious cult that will slowly take over her identity

#canaries belong underground#my ocs#original work#original character#kesone nang#aleksander lightcaster#jasmine masoumi

0 notes

Text

adrian lightcaster webweaving // all from pinterest

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

something something kesone nang is such a good person at heart that his selflessness borders on self-sacrifice, except it’s not as noble as that, it’s more like self-destruction, and he doesn’t know the difference because no one stops him before cain comes along, who knows what drowning is like and knows the loops and hurdles you go through to justify your own meandering suicide.

0 notes

Text

mutual destruction - keo; regarding return and change

“I didn’t recognise him,” is what Jasmine tells Adrian the first time they are alone together.

It sounds almost scandalous, for a man and a woman to be alone together after days of being in shared company, but Jasmine is not the type of woman to have such affections, and Adrian’s work is far too dire and far too consuming to allow him to engage in any romantic fantasies. Any and all of their interactions are shaded with suspicion and remorse, anyway; if Adrian had ever had any friendly feelings for Jasmine, and Jasmine for him, they had long been extinguished.

Now, they merely tolerate each other, as Keo tolerates Adrian’s presence and Adrian tolerates his absence, if only for the sake of humanity as a whole. Between the three of them - Keo, Jasmine, and Adrian - they have enough bitterness to drown an entire city. It simply isn’t a good idea for two of them to be alone with one another for too long, even in Jasmine’s and Keo’s case.

The opportunity that presents itself when Keo finally retires for the night is a unique one. Adrian is beginning to value the sporadic nature of his own nightmares, seeing as they only attack occasionally, and not during every waking hour, as Keo’s do. Jasmine, for once, decides to remain in the observatory, instead of seeking the company of the other members of the party she had arrived with. Adrian, despite the headache growing at his temples, and the constant ache in his back, has found himself in the mood for conversation.

“I didn’t recognise him,” Jasmine says, several minutes after Keo has left the room.

“That’s hardly surprising,” Adrian replies, cordial, though keeping his distance. “It’s been almost four years, by now.”

“Yet, you recognised me, and I, you,” she remarks. A slight huff of amusement escapes her, and when Adrian looks over, she is smiling - sardonically and without teeth - but it looks as elegant as ever on her features.

“Well, it seems as though you haven’t aged,” he says in answer. It isn’t a compliment. It’s the unadulterated truth; while the years had sharpened the contours of his face, and muddied the gleam of ambition in his eyes, Jasmine still looked like the captain everyone had turned to for leadership and honourable action during the war.

In a way, she almost seems younger, fuller-of-life, unburdened by the weights that hang across Keo’s and Adrian’s backs. Adrian isn’t naive enough to believe that, not when they’re having this conversation, here and now, but when Jasmine smiles, even as unkindly as it is, he feel as though he’s on the cusp of nineteen again.

Jasmine’s smile grows, and if it is in humour, or mockery, he cannot tell. “I suppose I haven’t. Not like you, or Keo have.”

“Does he seem older to you?” Adrian questions, and he would be lying if he said it was purely for curiosity’s sake.

Yes, and no, he answers himself, while Jasmine contemplates it.

Yes, Keo does seem older - considerably matured, leagues more composed now than the crackling, grieving thing he had been when he and Adrian had met first met. He had held himself with the dignity of a hardened war veteran, despite coming face to face with the man who had tried to kill him, a sharp contrast to the floundering of a boy trying to play general in a game where the pieces moved themselves.

(It is a disservice, really, to insinuate that Keo had been at all incompetent during his time as general, when it had been thrust upon him at the height of the conflict, and despite the fact it had seemed as though his only option had been to desperately scramble for purchase, he had managed to come out the other side victorious).

Simultaneously, Keo does not seem older, does not seem aged. It is his physical appearance that disconcerts Adrian to the greatest extent. Adrian knows the damage inflicted onto Keo’s skin as well as he knows the damage inflicted onto his own, and yet, there is not a single blemish on his face, or even a weary reluctance to his movements.

Keo could have passed for nineteen, if not for the look in his eye.

“It was the look in his eye,” Jasmine says, pulling Adrian from his self-absorption. Her words echo his thoughts, almost exactly, but the phantom sensation of her presence in his mind is starkly absent. “At the time, I thought to myself: living men don’t have eyes like that. That was all.”

“That was all?”

Jasmine’s gaze is piercing as she stares at him, heavy and deliberate, a dozen needles pinning him to his place by the desk like a moth in a display case. Adrian hardly breathes, abruptly regretting his words.

“That was all,” she clarifies without inflection, relenting as she moves her gaze from his eyes to one of the walls. “Even with the headache, and Cain’s predicament, all I could think about was how dull his eye was. Now, I can see that Keo has barely aged - if I had been in my right mind, I would have recognised him from a distance - but, then, I remembered him as an enemy first and an ally last. Especially when my memories began to resurface.”

There is quiet between them. Adrian isn’t sure what Jasmine’s and Keo’s last interaction had been like before she had deserted, but he doubts it is a fond memory in retrospect. They seem to have made up, for the most part, but their relationship is strained at best and fatalistic at worst.

“Did you recognise him?” Jasmine asks Adrian, though she knows the answer as well as he does.

No, he hadn’t recognised Keo - not when the boy he had cherished was less man and more monster now, and not when Keo’s eye was perpetually vivid blue instead of the warm brown Adrian remembered.

“I should have,” Adrian answers. Yes, he should have recognised Kesone Nang, the General Cyclops, one of the few good men left in the world twisted into something not-quite human. “It’s perculiar, isn’t it? That all it takes to turn someone into a stranger is the look in their eyes.”

“An altered perception of the world can turn anyone foreign,” Jasmine responds, cool and without reproach. She almost smiles. It is a very near thing. “I think I’m going to retire for the night. It is late, and there is work for us in the morning.”

“There’s always work for us,” Adrian says, voice full of mirth. He watches as Jasmine rises from her seat and carefully places her things in an orderly pile at the corner of her desk.

She pauses by the doorway, a strange expression flitting across her face, before it settles in blankness. She turns to glance over her shoulder, her gaze practically benevolent. “Has the look in your eyes changed, Adrian?”

Have you changed?

“What a convoluted thing to ask,” he replies demurely. He almost answers that yes, yes the look in his own eyes has changed, but it is too much of a lie to even speak. He may speak lies as easily as they are truths, from the common people to regents, but he will not lie to Jasmine. “What do you think?” he says instead, as though it will absolve him of his guilt.

“I think that we are very foolish, and still very young. Rest well, Adrian.”

“Rest well, Jasmine,” he says, watching as she slips out the door, entirely unsatisfied yet uncharacteristically unmotivated to chase an answer.

Perhaps the late nights are weighing on him more than he’d like to admit.

“You weren’t supposed to come back,” Adrian tells Keo the first time they are alone together.

It is no accident that Keo and Adrian are never in a room alone together, even with their uneasy truce. It is deliberate, on both of their parts, that there is at least one other person in the room with them whenever they interact, whether it be one of Keo’s allies, or a servant, or anyone else that might force them to be amicable.

That is not the case tonight. It is nearing four hours past midnight, and the only other person awake is the chef and a maid, both of whom would have returned back to sleep by now.

Keo and Adrian sit alone in the dining room.

Two people sitting at a table fit for twelve is uncomfortable, but the observatory is too intimate a space to be shared by only the two of them, and etiquette dictates that they are seated to take their meal, no matter what time it is.

Adrian sits at the head of the table, as he usually does, and Keo sits at his left hand side. This way, neither will have to look each other in the eye when they inevitably glance up from their plates.

It is almost four in the morning, and they are eating fried sticky rice with fermented sausages and leafy greens. This situation is not by either of their designs; they had been working, researching, it had gotten late, they had skipped dinner, Jasmine had fallen asleep at a desk, Keo had carried her to her room and bed, he had returned, and they had continued working in silence.

It’s almost funny to look back on, the mutual resignation and understanding that at one point, eventually, they would have to be in the same room as one another with no buffer between them, communicated through by nothing but a brief glance and the continued scrawling of a fountain pen.

Keo and Adrian had worked in silence, and now, when the dull ache of hunger had become a gnawing pain, and a maid had happened upon them with the knowledge that they had skipped dinner, they eat in silence.

Fried sticky rice. Fermented sausage. Leafy greens.

It’s an applaudable meal, especially one made in haste by a presumably very disgruntled chef. Simple but palatable. Familiar and comforting. Adrian eats with silverware, a fork in one hand, a knife in the other. He assumes Keo does too, until he realises that his utensils are the only ones scrapping against ceramic plate, and has the sense to look up from his meal.

Keo is eating with his hands. Hand. He uses his fork to push the sticky rice and meat into a leafy green, then wraps his fingers around it to bring to his mouth. It’s strangely meditative, and he seems focused on the task at hand, eye never rising from his plate.

Adrian goes still as he watches, his wrists resting on the edge of the table, knife and fork gripped tightly like weapons. He remembers eating sticky rice with his hands, almost a lifetime ago, surrounded by people he knew he could trust. He used to swear food tasted better when you ate it with your hands.

“It’s rude to stare,” Keo says, without looking up, without emotion.

Adrian blinks, but does not move his gaze. Something witty teeters on his tongue, a clever remark or some good-natured snark, like something he might have said four years ago. It never leaves his mouth.

“You weren’t supposed to come back,” Adrian tells him, the first thing he has said to Keo without an audience since the first day he arrived at the summer estate.

Keo takes no obvious offence. He reacts so little, Adrian almost doubts that he had heard him, but Keo is nothing if not uncannily discerning.

“If I recall, you were the one who organised to have me arrested at the coastline and brought to trial in front of the highest possible court,” Keo says so dryly Adrian wishes he had the levity, the privilege, to chuckle.

“I know I killed you,” is what Adrian says instead.

Keo’s eye finally leaves his plate, flickering up to meet Adrian’s, too brightly blue to be human, too dull in everything else to be living. “Do you?”

“I put arsenic in your food. I pushed you off of a cliff and into a river. I put a bullet through your head. I killed you and I know it.”

Keo looks at him in pure, unpolluted pity. “I didn’t realise dead men could speak.”

He returns to his meal, then, as though he has said nothing and Adrian has not admitted to crimes that would have him hung for treason.

Adrian, for the first time in a long time, feels his fingers curl so tightly into a first that his short nails dig into the meat of his palms.

“When?” he asks. When did you get back? When did you turn into something else? Then: “Why? How?”

“Two years ago I awoke in a monastery with an amputated arm and missing right eye,” Keo replies calmly, with the patience of a school teacher wrangling a noisy student. “I wanted to kill you. I wanted revenge.”

“You shouldn’t want anything,” Adrian murmurs, more to himself than Keo. It sounds ridiculous, but to Adrian it is true - Keo shouldn’t alive, and corpses have no wants or need. It sound ridiculous because everything about this is ridiculous.

Keo, in his infinite composure, doesn’t respond to that particular notion. “I thought you were glad to have me back.”

Yes. No. Maybe.

Adrian is in conflict with himself, and Keo’s stoicism throughout it all is enough to crack his careful facade of apathy and self-preservation.

“I didn’t recognise you when I first saw you,” he retorts.

Keo doesn’t comment on the seemingly abrupt change in conversation topic. He inclines his head, all but telling Adrian to get on with it, making no moves to argue against or support it.

“I don’t know about you,” Adrian says, low and steady. He doesn’t know if there is true vitriol in his words, or if he is so frustrated with Keo that he’s blinded himself. “But corpses shouldn’t want anything.”

“How unpleasant,” Keo remarks. He finishes his meal, wiping his fingers with a napkin, and stands in a way that makes the legs of his chair scrape against the marble floors. Adrian’s eye twitches. “Send my regards to the chef, it was an excellent meal.”

“Wait.”

Adrian stands so forcibly he almost knocks his chair over backwards. Keo does wait, because now Keo is polite and formal, even if he has his moments of snark, because he has moved on from his past, unlike the rest of them. He stands, and he watches Adrian, not unlike a curious predator observing a colourful bird that is just out of reach, still and unmoving.

“I- I am glad. To have you back,” Adrian stumbles over, chattering, like a nervous mouse. “It’s just that- You. You. You.”

“Adrian,” Keo says, very softly, as though someone might overhear him. Adrian wants to sob at the sound of his name, so free of bitterness and disdain, so easily spoken. “You’re swaying.”

The words filter in through Adrian’s ears, and the next he is truly swaying, knees buckling underneath his weight. Keo catches him before he can eat the ground. As he always does. Consciousness comes to Adrian in irrelevant waves, waning and yawning, teasing him with glimpses of the painted ceiling, with the sensation of his cheek pressed against Keo’s warm shoulders, with the creaking of a door opening.

Adrian only gains any real lucidity when he is being lowered into a bed, cool sheets against his cool skin, a pillow cushioned beneath his head. With the grace of a drunk man, he throws his hand out and finds cold metal, and holds on for dear life, half-suffocating his face buried into his pillow.

“Why?” he whispers, with the fragility of a disillusioned saint. “Why did you come back like this? Why did you come back with the wrong look in your eyes? Why did you come back changed?”

When Keo replies, Adrian cannot see him. He cannot see anything at all, blinded by the humiliation of his life, and the shame of his continued existence.

“Why haven’t you?”

“I’m sorry,” Adrian says, as everything begins to fall away from him, like he has turned his back on the world and it has turned its back on him. “I’m glad you’re back. I’m glad. I’m glad. I’m glad.”

“I’m sure you are,” Keo replies. Cold fingertips pull the stray hairs out of Adrien’s face, delicately, tender like Adrian has never been able to be. Their touch is fleeting, and when it’s gone, Adrian wants to chase them and hold them by his cheek until they grow warm.

“Don’t go,” he thinks he says, or maybe he doesn’t, because the presence at his side disappears, and the room grows cold.

“I’m sorry I came back wrong,” he thinks he hears beneath the creak of a door closing, beneath the growing thud of his dead heart, and beneath the keening of every regret and sorrow he has buried in the marrow of his ribs.

#kesone nang#adrian lighcaster#jasmine masoumi#canaries belong underground#resurrection#came back wrong

0 notes

Text

“do it, it would be so slay,” the angels say as they convince adrian to burn all of his relationships into the ground, brutally slaughter his best friend and closest confidant, and construct a reality where he was born rich, denying his heritage, in order to be accepted into high society to further his own goals that are at their core for the sake of humanity

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

the title “canaries belong underground” refers to the practice of bringing canaries into coal mines to detect the presence of toxic gases, primarily carbon monoxide poisoning, as they were more sensitive and would become ill before miners, allowing them to leave the mine or equip respiratory masks. when they became ill, they stopped singing, and so they were used as an early warning system - animals like these are known as sentinel specifies. canaries in mines were used as early as 1896, and in some cases, would have a dedicated oxygen tank so that they could survive after giving warning of the toxic gases.

canary, in respect to the novel, refers to the main cast. each serve as a reminder of how trauma can shape an individual, and as a warning for what may be to come. underground often alludes to an unsavoury or out-of-the-way location, in this case, the fringes of society, where the ensemble cast has been pushed out to by their trauma.

the title is also a highkey anachronism. by late 19th century, telephones, automobiles, and typewriters had been invented, and so by referring to the practice of using canaries in mines, i am inadvertantly referencing a reality that does not yet exist in the context of the novel - and as much as i like the significance of the title, it just doesn’t… satisfy me.

still, it’s the only title i’ve come up with that even vaguely fits the themes and characters of book, so, ill leave at this for now…

#my ocs#oc stuff#fantasy#original character#original work#just messing around#what am i doing#canaries#novel idea#books

1 note

·

View note