Hi, I'm GB. I have a compulsive need to write about games. Occasionally, I try to make them. Stick around, would you?

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Let’s Talk About The Microsoft Store.

So, uh, here’s the deal: this is a huge pain to reconstruct on Tumblr, which doesn’t preserve Google Docs formatting at all, and, worse still, really, really sucks at image placement in an article.

On Medium, you can simply copy and paste the article from Google Docs.

On Tumblr, you copy the entire thing in, then find the images are gone, and have to add each image, manually, one by one. But Tumblr won’t let you just paste an image where you want, oh no. For some reason, when you add an image, it ALWAYS pastes to the top of the article. Then you have to physically drag that image down into the article until you get it where you want.

Since this thing is 35 pages long (with images) in Google Docs, uh... yeah, I’m not doing that. Read the article on Medium:

https://medium.com/@DocSeuss/lets-talk-about-the-microsoft-store-c023789e6642

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m Taking Commissions

Hi, I’m Doc. You might know my blog, http://thesto.mp. It’s where I write about video games. Or you might know me from my work on sites like Kotaku, PC Gamer, PC World, and US Gamer. I’m taking commissions to write about video games, because I’m in urgent need of medical care and a place to live at the end of July.

I write stuff like this.

What: For $100, I’ll write about almost any video game you want me to, except for Half-Life 2 (I’ll cover that one for $2,500).

For $250, I’ll make a YouTube video. I’ve got a new mic and have an editor I’ll need to pay so the video looks cool.

When you commission an illustrator, you commission them for their style; I have my own distinct approach to games writing, which you can see in the portfolio down below. What I love doing the most is explaining how a game works or how it doesn’t.

Earlier this week, I jokingly said I’d explain why any game you like is good, even Uncharted 2. Someone pointed out that this made it sound like I’d say whatever anyone wanted to hear. My belief is that a good critic keeps his integrity intact.

I don’t like Uncharted 2, for instance, but it’s an undeniably popular game. If someone wanted me to write an article explaining why so many people love Uncharted 2, I could do that with complete honesty. I can see the appeal, even if I don’t find it appealing. I won’t write about something I can’t cover honestly.

Restrictions: I reserve the right to turn down anything for any reason. Sure, I’m desperate for cash, but I have to weigh the cost of access and time spent with $100. If you want me to cover Panzer Dragoon Saga, I would have to buy a Saturn ($70) and the game (~$400). I can’t afford to spend $470 for $100 in return. There are also some genres I’m just not good at, like MOBAs, so I can’t offer you the level of writing I’m used to.

That said, if you want me to write “A MOBA perspective from someone who’s never played a MOBA before,” I can do that. I’ve done that before.

Why: I am losing my apartment on July 31. I need to see a doctor. I need to see a dentist. I’m doing what I can to sell what I have, because I owe money for things like a car repair and taxes. I need to get an oil change. Three amazing friends hooked me up with some grocery money, which is great, because I’ve been eating one meal a day for the past few weeks. I ended up spending some of it on medicine.

The ear infection I was fighting yesterday hit me so bad that I crawled into bed in the middle of the afternoon, downed as much Advil as is safe, and fell asleep. It still hurts.

Why not just work a minimum wage job? Believe me, I would, if it weren’t for my severe health issues. I’m crippled and stuck at home. What little work I can get, I’ll take.

I don’t mean to be a big ball of negativity or anything, it’s just that life is bad, and because life is bad, I have decided to start doing writing commissions.

Why $100? Well, because that’s my minimum professional rate.

Let’s say a game takes 15 hours to complete for an article. $15 at $7.25/hr, minimum wage, is $108. Less than minimum wage. That doesn’t even count the cost of the game itself, though most of the games I write about are things that I got and played a long time ago.

Portfolio:

The Unusual Excellence of Halo’s Best Level: http://kotaku.com/the-unusual-excellence-of-halos-best-level-1631041139

The Best Video Game Shotguns: http://thebests.kotaku.com/the-best-video-game-shotguns-1749589146

How Crysis’ Level Design Works: http://www.pcgamer.com/revisiting-crysiss-amazing-fps-sandbox-how-the-series-lost-its-way/

Why Mad Max Is Underrated: http://www.usgamer.net/articles/mad-max-underrated

Payment info:

If you’re into this, send me a tweet or a DM (I’ve got open DMs). I’d appreciate any RTs or shares. If we agree on it, you can send me some money at http://paypal.me/stompsite

If you’re interested in supporting me regularly, please consider supporting my patreon at: http://patreon.com/docgames

If you know of anyone hiring someone to write about games, do mock reviews, or consult (I’ve worked on a dozen or so AAA games as a consultant!), please let me know. Anything I can do to find stability soon, I’ll take.

Current Commissions & stuff I already have planned:

* Clam Digger * Receiver * Minesweeper * The Crew

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I haven’t been happy with my writing for months. There was a time when I’d have an idea, I’d sit down, I’d write it, and I’d be happy with it. A line of thought ran through each piece, I could follow it, and I was happy with it.

There’s a couple reasons for this. I’ve had more pieces rejected than ever before, and, more importantly, I’ve understood why they were rejected each time. It feels like I’m slipping, like I’m losing my grasp on good writing.

Shit’s been bad, of course. My health has declined, and I’ve been unable to treat it. I was on a podcast, then booted off because... I have a Patreon and can’t talk about the freelance work I do. Never mind that I didn’t, y’know, talk about the Patreon on the podcast.

In September, two guys came on board G1′s team. The first day they were there, they had a meeting without me where they tried to change a bunch of details about the game. Y’know, the game I created. The game that I had recruited everyone but them for (one of our programmers did that). I was alerted by a team member, showed up, and politely explained that if they had ideas for improving the game, I’d be happy to discuss them and approve them.

The next day, the guy who recruited them dragged everyone into a meeting where he said I shouldn’t be in charge of the game, and eventually revealed that these two guys--who hadn’t actually WORKED on the game, just tried to change it conceptually--had threatened to leave because I was “an asshole” to them.

Later, we found out they were trying to break the team apart because they wanted a programmer. Well, they got one. They got him to announce that he was leaving because he was “just too busy.” They tried to recruit my other programmer too, all to work on their game. When I asked the programmer who was leaving if he was leaving to work on another game, he launched into a massive tirade about how he didn’t know who I was, whether I was truly sick, or a bunch of other stuff.

He never admitted he was quitting to work on another game. In a matter of weeks, he’d gone from “this is really happening, I can’t wait to see it work” to telling other team members the game would never happen and we should all give up.

It was demoralizing. It’s still demoralizing. I watched a friend get suckered into nearly destroying our project.

The stuff I’ve written that I’m happy with is stuff I recognize needs work, but it’s also stuff that doesn’t feel right. Like, nobody is going to want to publish it. Game developers seem to like reading it. Nobody else does.

I can do things like news, interviews, and reviews, but that’s not what you hire a freelancer for, right? Most of the sites I read don’t swing that way. They want their staffers to do news and reviews. Freelancers do other things, and the things I do are, I guess, kind of limited. I don’t know how to expand that.

I wrote a piece last night. Fought through horrible brain fog to do it. In the end, I wasn’t happy with it, only submitting it because of the deadline. It’s not the first piece I’ve written like this in the past few months. It’s frustrating me. I tried to write about disability in games, and all I ended up with was a huge turd of an article that sounded like a cry for help more than anything.

My health is getting worse.

I’m increasingly concerned about how much time I have left if I can’t earn enough money to seek medical treatment.

I don’t know how to sustain myself. All of my freelancer friends are moving on to full-time jobs. Only a couple are still freelancers, and there’s a good chance they won’t be for very long.

It feels like so many people have abandoned me. I don’t even have a roommate any more. I don’t know how I’m supposed to survive. I’m doing the best I can, but I’m still drowning. Will I find land before I die?

My body hurts so bad right now.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey man! I saw your article on Kotaku about F.E.A.R, great read! I wanted to let you know of another achievement that game provided. I was a developer on F.E.A.R. 2. Jeff Orkin wrote a breakthrough AI technology called GOAP (Goal Oriented Action Planning) that has gone on to be implemented in many games and create dynamic AI that does things the developer didn't explicitly implement. It's what caused the AI in that game to be so well received. This is worth adding to your article. - C.J. Clark

Hey! I’m really familiar with his paper on the topic--Three States and a Plan. I thought about including it, but couldn’t work it in how I wanted to, so I ultimately elected not to.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Woe Is Me

Hey, haven’t been talking here much, ‘cause life’s been busy. I graduated and stuff, which was cool.

But right now? I need to vent. I don’t need pity or anything. I just need to feel like I’ve been heard. Helps me deal with stuff.

So.

Here’s my past week:

On Sunday, my laptop dies. It costs $40 to send it in, I wasn’t able to back up all the data on it because some of it’s locked away in my OS.

On Sunday, my tooth comes out. I start looking for ways to get it taken care of.

On Monday, someone I sold my old GPU to asks me for a CD. I tell him there isn’t one, but I tell him what would have been on it and where to get it.

I don’t get paid like I’m supposed to for some freelance work I did. I start tracking it down. Needless, frustrating hassle.

My desktop computer dies too. I’m computerless. I start trying to find out what’s wrong.

On Tuesday, he replies angrily, saying he wants a refund. I actually have located the CD and tell him I can send it to him at no charge if he still wants it.

He replies saying the item is defective and doesn’t work. That’s new. It worked when I shipped it, and he didn’t have a problem for the six days after it arrived.

I contact Amazon.

On Wednesday, I’m finally able to get it fixed. Yup, it hurts a LOT. Also it cost me $80 that I was gonna spend on things like groceries.

I also find out that the $300 check I’m expecting on Friday isn’t coming. I was gonna use that to pay $100 I owe on my car.

Thursday, I just kind of surf through the day. It sucks. I’m worn out. My mouth still hurts but the Advil I had to spend money on (because while I’m in chronic pain, I try to avoid painkillers as much as possible due to worries about dependency and my doctor’s recommendation that my liver can’t handle many painkillers).

And now it’s Friday. 76 hours after I contacted Amazon, with no reply.

I had to sell my Xbox to make the $100 payment. It’s kind of cool; I have a good reason to get an Xbox One S now, but still. Kinda sucks.

Amazon finally gets back to me--except, wait, no, it’s a different department, the A to Z department, and they’re saying that I’ve never replied to the customer (I have), and if I don’t reply within seven days, they’re going to charge me money I don’t have (because I spent it on bills) to reimburse this guy who’s trying to scam me, who’s changed his story every time as to why he wants a refund, and all this other stuff.

I reply to the email. It bounces.

I contact them again. No response.

I try replying to the email again (it says to do so!). It bounces again.

I tweet about it. I get a response. It says to contact them at the place that I have contacted them (six messages at this point, and the only action Amazon has taken is passed it along to a new department, apparently).

I point out that I got no response.

“Well, try contacting them about that.”

“Contact the people who haven’t replied to me to complain about them not replying to me?”

“When did you first get in contact with us and what did we say?”

“Tuesday, and you didn’t say anything.”

So now I get a new link to contact their social media team on their website. I have received an email from them.

I have also emailed Jeff Bezos, because why not, he says his emails are open. It’s much nicer and politer than this.

There’s minor stuff too. Brief panic after I got shortchanged when selling my Xbox. No reply from people I canceled a preorder with because I can’t preorder many games. My shorts have ripped and I can’t afford to buy a new pair of shorts. My health is still super bad, though better than a few weeks ago. It comes and goes.

But here’s where I’m at:

I’m sick. It’s still untreated. I can’t work regular people hours because I’m sick. I can’t treat it because I can’t work a regular job to pay to get it treated. If I could pay to get it treated I could actually function.

So. I’m dealing with that. This week has been hell. I might have to pay Amazon $305 for a GPU that apparently has been broken by the consumer. I don’t have any money. They only paid me $280 for it, so that’s me out $25 for no reason other than a scammer and Amazon’s reluctance to get a hold of me. I was supposed to get $300 that I didn’t get, and I had to sell my Xbox for $100, which means replacing it (which I gotta do for work, since I get paid to, y’know, write about Xbox games) is gonna cost me another $300 or so.

I’m out the money to replace my hard drive. I’m out $80 to get my tooth fixed, and they’re telling me that I need a LOT more work done sooner rather than later. I feel like I’m dying here. Like nothing good is happening. The best thing that happened was that the person who shortchanged me was happy to help.

I am so stressed that my heart hurts and I feel like I’m going to throw up.

I need something good to happen. And it hasn’t.

I’m tired and I want to sleep my problems away, but there are no solutions in sight. I’m too stressed to finish this Bioshock video, and I don’t have the hard drive space to record Bioshock footage right now. I’m so on edge right now that all the pitches I’d hoped to send to various websites this week aren’t working out.

Oh, and my roommate never gave me his 30 day notice (because right after our conversation about me needing one, I told a friend who had discussed rooming with me that I was waiting to hear from my roomie when that would be), and thinks he’s moving out in 14 days, but hasn’t even bothered to do anything in regards to the water bill or talk to our landlord about being taken off our lease. And he thinks I’m misremembering and he totally did say “well, then I’m moving out in 30 days” right in that conversation, but if he had, I would have said, right then, “okay, so have you taken care of the water/talked to our landlord about the lease/etc” and I didn’t. Because that is the conversation I’m going to have with him when he does.

So now he thinks he’s moving in 14 days, while he still owes me a lot of money, and doing so will greatly increase the cost of living here. My Patreon needs $1,250 for me to survive completely on my own here. I’m trying to freelance more but holy crap, all this STUFF. A few weeks ago, they put down my other dog (that’s two this year) and a family member who had what I have died and all this other stuff... like, it never seems to let up, and when it does, I got other stuff to do (like a ton of consulting, which is awesome), but when THAT lets up... then this comes back. I need life to slow the heck DOWN.

Oh yeah, and my domain’s expiring super soon and my host’s expiring soon and I need to get this stuff taken care of, but I’m so spent, so utterly spent, dealing with an illness so bad I can barely function normally on a good day and all this crap of this week... I’m just... I feel like collapsing. I’m devastated.

Update: Amazon has not reviewed my case, claims it has, rejected the claim, expects me to pay the guy money.

Update 2: Holy crap, the USPS messed up and sent my laptop to ME, even though the postage/receipt says to ship it to the repair center in California. A week has gone by and my laptop is nowhere near close to California.

Update 3: USPS says they will require me to waste time and money going to the post office, where they will redo the entire process, and ship my package, a week late. They refuse to, say, update it to overnight because THEY screwed up the shipping. I paid for it to arrive on Monday. Now it MIGHT arrive NEXT Monday. I might miss the RMA window thanks to these clowns.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

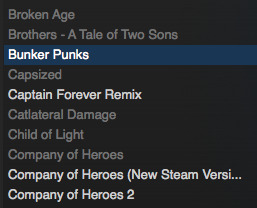

Bunker Punks has been spotted in my Steam Library. Early Access announcement coming soon!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Please Stop

I have noticed from maybe the Neptune orbit to the Oort Cloud of my social media universe, that in games and in “social justice” and very especially at their intersection, there is a huge “throw the baby out with the bathwater” problem right now, and it’s starting to grind me down a bit to see it.

Keep reading

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ll Bet You Think You’re A Good Person

New school essay, submitted for finals, so I can totes post this on my own blog now.

1. Good people My stalker thought he was a good person. I know this because, even as he tracked down employers and coworkers to insist that I was a scammer who only wanted money from them, he was telling me that he was a good person. I don’t remember his name now; I tried hard to forget, and it worked, but I still find myself occasionally panicking about it.

He was following me because I’d asked an online community for advice; I’d recently been let go as a result of my ailing health, and I was stressed and scared. Having made some good friendships on this particular community, I figured I could trust them. Many people offered their assistance. Some encouraged me to start begging for funds, but, because it was the rules, I turned them down. I just wanted advice, I insisted, on what to do next.

Then he came along. He believed, after examining my symptoms, that I was some sort of pain addict, that, despite my turning down any funds, I was asking for money so I could go buy drugs. This set off a campaign of harassment until he was banned from the forum and social media services.

Most people think they’re good people, and I used to believe everyone was, but because of people like my stalker, it’s become a lot harder to trust that this is true. For the past ten years of my life, I’ve been the victim of good people who think it is okay for them to be anything but.

2. Visible Disibility

When someone says that someone else is disabled, we conjure up certain images in our heads. This person must be in a wheelchair or use a walker; perhaps they have a service dog or wear thick glasses and a carry a cane. They might look unusual, as the result of a birth defect or traumatic injury, or they might speak or act strangely, with slurred speech indicating deafness, or with the particular gait that accompanies various muscle disorders. Disability, in most minds, is clearly visible. We conjure up mental images when we hear that word.

Many people feel awkward or comfortable around the disabled. It’s hard to know how to act, challenging to feel comfortable around someone who isn’t “normal.” There are concerns about what to say and how to act, fears that one might make the slightest mistake and make everything worse. Some people have an easier time working with the disabled than others, going out of their way to be as helpful and compassionate as they can be, and it’s wonderful. But here’s the problem: disability isn’t always visible. You’ve no doubt heard of learning disabilities, for instance, and have probably heard the stories about how people treat individuals who struggle to learn. Someone with dyslexia, for instance, might not have trouble getting around or carrying on a conversation, but people will assume they’re stupid because they may struggle to read. Someone close to me was put in the remedial class for dyslexia. My grandmother’s sensitivity to strong chemical odors offended one woman so much that she refused to attend church with her. Other invisible illnesses include chronic pain or fatigue, severe chemical sensitivity, migraines, and so on.

I have a debilitating invisible illness too.

I wish I could tell you what it was. I wish I could cage it by giving it a name. I wish I could tell you that it was cancer or AIDS or something people could wrap their head around, because if I could, then maybe, just maybe, I wouldn’t have to deal with people like my stalker.

3. A Decade At Sea

You have been shipwrecked. To survive, you must tread water, so, of course, you waggle your legs around and hope you find some way out of your predicament, but the hours pass, and you spy no wreckage, nor land, nor passing boat. You are alone on the surface of a vast ocean, and you must tread water, or you will drown.

Eventually, your muscles will start to cramp. The pain becomes too great to move, and you begin to sink, the saltwater finding its way in through nostrils and pain-clenched teeth, and then you’re choking, drowning, dying, lungs screaming for air, and the only way—the only way—to stop this is to fight through the cramp and start treading water again.

Ten years later, you’re still treading water, still cramping up, coughing water out of your lungs and wishing, hoping, praying that someone would come by with a life preserver.

4. Symptoms

The story goes that when Jesus carried the cross to Golgotha, he was in so much pain that they had to invent a new word for it—excruciating—which comes from a Latin word that more or less means “out of the cross.” You’ve doubtless experienced pain before, but have you ever experienced truly excruciating pain? Have you ever hurt so bad you felt like you were going to die?

I have.

There are different sorts of pain. There’s the sharp pin-prick of a hospital needle puncturing the skin, the dull throb of a bruised muscle, there’s about a dozen different kinds of headaches, from sinus to cluster. You’ve doubtless felt the various aches and pains humans feel on a daily basis, and maybe even the more severe stuff like repetitive stress injuries or arthritis.

What I have is next-level kinds of pain. I feel like each muscle has been individually wrapped in plastic wrap, then compressed to an agonizing degree. It hurts to move anything. It hurts to sit still. There are times when I wish I could cut off my arms and legs to stop them from hurting, when I think about hunting down some drugs to make it all stop, when it gets so bad that I feel like I’m doing.

I loved sports when I was younger, whether it was traditional team sports like basketball and baseball, or more adventurous stuff like rock climbing or skiing. I’ve scaled a 14,000 foot mountain without proper acclimation, and I’ve squatted three hundred and fifty pounds for twenty reps. I’ve pushed myself hard at times, and sometimes, it’s been too hard. Sometimes you hit a point where something tears, where your body demands you stop because something is very, very wrong. It’s a different kind of pain, and now, with this disability, there are days when I wake up and I feel like I’ve worked out too hard, even though I haven’t done anything. Instead of ‘normal’ levels of heightened pain and fatigue, I start to feel sore and weak, like muscles have been torn and I’ve exerted myself too much. When I want something to drink, I start carrying around plastic bottles with screw-on lids because I’m afraid my strength will give out and I’ll drop a glass and spill water everywhere.

If it isn’t one kind of pain, it’s the other. It always hurts. It’s never comfortable. It’s a prison, and I’m serving a life sentence.

Fatigue is even worse. Imagine the worst flu you’ve ever had in your life. You know how it keeps you down, makes you want to stay in bed, makes you wish everyone would just leave you alone and let you rest? I’ve been through some pretty bad flus, but nothing—and I do mean nothing—compares to this level of fatigue. Some days, I am physically incapable of getting out of bed. It would be nice if I could plan around this by going to sleep earlier, but have you ever been too exhausted to sleep?

One of my problems is that my body’s ability to absorb and process magnesium is severely diminished. This results in drastic magnesium deficiency. Here are a list of symptoms, from Wikipedia.

Symptoms of magnesium deficiency include hyperexcitability, muscular symptoms (cramps, tremor, fasciculations, spasms, tetany, weakness), fatigue, loss of appetite, apathy, confusion, insomnia, irritability, poor memory, and reduced ability to learn. Moderate to severe magnesium deficiency can cause tingling or numbness, heart changes, rapid heartbeat, continued muscle contractions, nausea, vomiting, personality changes, delirium, hallucinations, low calcium levels, low serum potassium levels, retention of sodium, low circulating levels of parathyroid hormone (PTH), and potentially death from heart failure. Magnesium plays an important role in carbohydrate metabolism and its deficiency may worsen insulin resistance, a condition that often precedes diabetes, or may be a consequence of insulin resistance.

I have most of those symptoms.

And it’s not just that. My neurotransmitter levels are low. I’m zinc deficient. I have a host of symptoms that travel beyond that.

5. Good People, Part Two.

So, that’s my life, such as it is. Every day is fraught with pain and exhaustion. I’ve learned to deal with it, in a manner of speaking. I eventually force myself out of bed, attend a few hours of classes, and go back home, lie down, and watch some TV or read or play some video games, assuming I have the strength to do that. Right now, I survive on food stamps, two writing jobs, and a consulting gig. My employment is mostly at-home, because there’s no way I’d be able to survive a 9 to 5 job like most people. Still, I can bear it. It’s hard, and some days, it’s practically impossible, but I fight through the pain, I get out of bed, and I get done what needs to get done. Yeah, I’m no longer the punctual, outgoing guy who always had time for everyone, but at least I can function. The biggest problem I face is other people.

It started with my parents, over a decade ago, when my symptoms were first manifesting, but I wasn’t really “sick.” They chided me for what they saw as an increasing lack of responsibility. I’d been a good teen before, but then they stacked three summer camps back to back, and I just could not handle the third one. They chose to believe it was because I just didn’t want to go to church camp with the rest of the family. Thankfully, as my symptoms progressed and we spent dozens of hours having doctors explain things to us, my parents gradually learned to work with me and my illness.

A few years later, when my illness hit its first major peak, I moved in with my grandparents up in Kansas City so I could go see a doctor at the KU Medical Center on a daily basis. The treatments I underwent there often left me drained, so I’d come home from my appointment, flop in bed, and fall fast asleep. This, of course, impacted my sleep cycle, so my grandfather took it upon himself to passive-aggressively alter it by entering the guest room, where I slept and he kept his stationary bike, and would begin vigorously training on his loud, old machine, forcing me to wake up. To him, I wasn’t disabled; he was missing a leg. That was disability. I looked like a big, strong boy—something he mentioned often. I should have been able to handle anything—regardless of the fact that I was living with him so that I could go to the hospital on a daily basis.

It got to the point that I had to move in with my aunt. For a while, things went well, until one day, I returned home to find my clothes missing. I asked her where they had gone, and she explained to me that when her children didn’t attend to her responsibilities, she took their possessions until they did. My inability to locate a job while living in the Kansas City area, she insisted, was the result of my “laziness.” Really, it was just the fact that nobody wanted to hire someone who had to go to the doctor almost every day of the week. Three hundred job applications in two months had proved that to me. No matter how hard I worked, no matter how good the “I am living with you because I need to go to the hospital” excuse was, the response was the same: how could a big, strong boy like me not find any work?

When we couldn’t afford any more treatments, I moved back to Wichita. I finally found work, explained some of my limitations, and promptly found my new boss ignoring them. She couldn’t understand why the massive, glue-based retiling of one of our buildings exacerbated my symptoms, accused me of wanting cushy treatment, and forced me to work as close to the construction as possible. Whenever someone needed heavy lifting done, I was always called upon to do it because I looked like “a strong guy.”

After I transferred to KU, I worked two semesters in a lab. The teachers I worked with all loved me, telling me they couldn’t wait to see me the next year. Students often brought me candy. The people there were kind and pleasant, except for my boss. She was happy to talk about how food poisoning had kept her up all night with puking and diarrhea, but if I ever said anything about my symptoms, she got upset. I found out later that she complained to other coworkers about the one time I’d told her about my symptoms (she’d asked why I wasn’t looking well), and she was looking for a way to fire me and hire me for someone healthier. Eventually, she did just that.

It happened at my next job too. I was hired with the understanding that I could do every job asked of me except work with mold. My boss promised me she’d never make me work with mold. Fast-forward a year and she decided to have me sort the theatre’s library books. I got sick, had to go to the hospital, and a few weeks later, received an email saying “jobs aren’t getting done that we need to be completed, so we’re letting you go.”

It’s not just employers and family, either. It’s teachers. Coworkers. Friends. Acquaintainces. My siblings talk down to me about why I rarely leave the house—they tell me it’s good for me, it’s healthy and important, that being a “shut-in” is bad. I’m not a shut-in, of course, I just struggle to get out of bed most days. I rarely have the strength to deal with crowds or parties. I want to hang with my friends, but I can’t.

That’s been my life for the past decade. To so many, it seems that everything I do—or don’t do, as the case may be—is an inconvenience. And it is, don’t get me wrong, it is. It would be wonderful if everyone everywhere could do and be and function and act as capably as anyone else, but I can’t. I would love to have been able to sort moldy books for the KU Theatre department. The fact that I could do nine of the ten tasks required of me is definitely not as good as being able to do all ten. I understand that.

But is that really fair? I am fighting against disadvantages that few people have. I’ve been told by doctors, back when I could afford them, that I was the sickest patient they’d ever seen, that most people in my position had given up and it was inspiring to see me continue to work for this, that “based on the numbers on this chart, you shouldn’t have been able to get out of bed today.” The doctors always said it in ways that were meant to be encouraging, but doctors are supposed to be have a good bedside manner.

Most regular people just wonder what’s wrong with you, and when you tell them, their instinct is to go “nah, you’re making that up. What’s actually wrong with you is a character flaw of some kind.” This leads to them going out of their way to hurt you: I got fired by people who had no compassion. At least one was in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act, but knew I had no way of challenging the termination. My grandpa’s passive-aggressive cycling actually went counter to the doctor’s orders to sleep and let my brain recover from treatment. My aunt stealing all my stuff was just plain rude. I’ve been screamed at, physically attacked, screwed over, lied to, and been called useless more times than I can count.

Truth be told, I am terrified of what my future holds.

6. What it all means

Living with my symptoms would be manageable if I lived in a supportive society, but I, and everyone dealing with invisible illnesses like me, has to put up with a massive wall of mistreatment. These people struggle so hard to understand the concept of invisible illnesses that it’s easier for them to assume that the sick person really just has some significant character flaws. I’ve seen so many people who relish the thought of letting their bad side loose, and mistakenly unleash the worst they have to offer on those of us who need their help and compassion. I can’t even begin to count the number of times where people have followed up their abuse with statements about my character, about how it’s not their fault that I’m a bad person, about how righteous they are to treat me as unfairly as they do. One person took it so far that school security had to pull them away from me and told me I should press charges. Recently, I found, on an internet forum, a discussion of a blog post I’d made explaining my illness as a sort of FAQ page for people who’d been asking. This forum discussion involved some individuals who believed me, but many were skeptical. One suggested that it was entirely psychosomatic, and others agreed. Another couldn’t believe that people would treat me poorly if I was sick—it must, he believed, have been a character flaw. The worst comment, I think, was someone who believed I was making it all up, because “modern medicine knows everything there is.” He believed there was no way that I could have an illness that modern medicine didn’t know about.

I have, in my darkest moments, wished that I would get cancer or something similar, because then, at least, people would understand me. Having an illness that’s as invisible as it is nameless—and trust me, I’ve been to a dozen different doctors, none of whom could name it. One simply told me that what I had was “just some mutated genes. It’s so rare it doesn’t have a name.” The idea of basic human kindness has gradually faded and been replaced by the gut feeling that everyone I meet devalues me until I can make them understand. It’s one thing to deal with constant pain and fatigue, but another thing entirely to deal with human beings who simply do not understand A year ago, I shared an FAQ blog post about my health due to repeated questions about it. I recently discovered that an internet community had found my post and proceeded to tear it apart, questioning my integrity, whether or not I was simply crazy and my symptoms were real, and so on. Not a day goes by that people don’t doubt what I have. When you see someone without a leg, you don’t demand they prove that having one less leg makes it harder to walk, do you?

And that’s my life. That’s what it’s like to live with an invisible illness. That’s what it’s like to function, every single day. If the pain doesn’t get you, good people sure will. I don’t mean this to sound like a pity party. I certainly don’t want pity. What I want is understanding. What I want is for people who hear “disability” not to simply think of what’s visible and what isn’t. What I want is to stop suffering. The least that anyone could do is give me the benefit of a doubt.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Short Story #2

Here’s my second short story for my creative writing class. It’s been discussed in class, there’s stuff I’m going to change, but I want to present this first draft as it is.

The trees were damp and dead, desperate for spring. Ugly, grey patches of snow could be found every few feet, yellowed grass half-heartedly rising up in clumps wherever it could. Still, I enjoyed the crack of the flames, the scent of the smoke, the raucous cheers of my comrades as they won this or succeeded at that. We were camping, and camping could be fun in any weather, even something as dour as this.

“He’s real management material,” I heard Mister Campbell say, and I knew he was talking about Roger, because Campbell never spoke positively of any boy unless it was Roger. I suppose every father has a right to speak highly of his son, but when you’re supposed to be supporting all the boys, because you are an assistant scoutmaster and that’s an assistant scoutmaster’s duty, it comes off poorly.

“Can we go hiking?” Roger asked, seemingly unaware of his father’s adoration. Roger looked at me, as if I had the power to sway his father’s mind. “I want to go hiking.” Campbell considered it a moment, but not really, then shook his fat head, his brand new, industrial-looking foldable camp chair creaking, and offered some excuse that I don’t recall. I sat in someone else’s chair, don’t recall whose. There were about a dozen chairs pulled around the fire, and Campbell was the only other one around the fire.

Campbell impressed me back then. He seemed big and confident and successful and self-assured. I knew he was management with the town’s biggest employer, but nobody ever told me what that meant. My own dad, the scoutmaster, was an engineer. He designed welding equipment. He solved problems that kept airplanes in the air. This I understood. Campbell’s role was less-defined, but all I really needed to see was how the other parents treated him, my own dad excepted. It wasn’t that dad disrespected Campbell, because Dad respected everyone and treated them all the same. I’d later learn that Campbell did not appreciate this. Dad would happily defer to the cop who told us about drugs or the falconer who showed us his hawk, because they were experts, and he respected that, but Campbell was treated like all the other parents, respected equally with all the other parents, and asked to work just like all the other parents.

We sat alone around the fire as he poked it with a stick, which spread the wood apart. He mumbled something about giving it air, but all he did was cause the coals to die down. I knew he was wrong, but I was still impressed with his imperious confidence. Something was bothering me, too. If any other son asked their fathers or the scoutmaster or the assistant scoutmasters to go hiking, the answer would have likely been in the affirmative. Campbell didn’t extend that son his courtesy.

Mister Bear ambled up. I didn’t like him. He was the sort of person who would make up things for good reasons, but all that ever did was annoy people. Once, he’d shouted at us, saying we had “only thirty seconds left” as he tapped at his watch during a timed exercise, but I looked, and he had no watch. He was simply pretending. Bear the Liar. I had no respect for him.

“Hey, why ain’t you doing your duties?”

“Did ‘em,” I replied, jerking a thumb towards the eating tent.

“You probably got something else to do.”

“Nope.”

“Then why ain’t you hanging with the boys?” He directed this question at me, and not Roger, who had picked another empty chair near the fire and was haplessly carving some wood. I thought about mentioning that he wasn’t being safe, but the thought of Roger’s dad getting mad swayed me. Plus, I was talking to Bear, with that weird, distant gaze of his that always made me uncomfortable, and he’d asked me a question.

“Felt like sitting around the fire.”

“That’s for scoutmasters like us,” he said bluntly, taking a seat and sighing theatrically. Bear always looked thin and sick, yet some part of him was strong. He was a welder or a mechanic, all wiry muscle in the arms and thin and flabby in the gut. Real blue collar guy, totally self-conscious. His long, straw hair—and I mean that in texture as much as color—was coming out, but I don’t think I ever saw him wore a hat unless it was real cold.

I didn’t reply. Just sat there, staring into the flames. Bear forgot all about me. Struck up a conversation with Campbell. “How do you do, sir?” he began, because he knew his place with Campbell, and soon they were chatting about things that boys didn’t, or wouldn’t, care about, like politics and religion and things that were boring. Roger got up and left; I glanced up, watched him go, then returned my attention to the fire.

It wasn’t long before Rusty showed up. I liked Rusty then. He had a streak of rebellion in him, which I was just discovering myself, and he was confident. Rusty liked me hanging around, I think, because it made him feel good, but something always felt ‘off’ about him, and when he and his parents ended up quitting a year years later, well… I wasn’t sad to see him go. But this was a different time, and I still looked up to Rusty, even though I questioned his judgment a bit too often, and even though I’d just won the election and was going to become Senior Patrol Leader instead of him. He said he didn’t care, though, so I thought we were square.

“You wanna go on a hike?” he asked me. This caught Bear’s attention, and he said “yeah, get you boys some exercise. Leave us old men be.” Campbell made a grin that was, for him, a chuckle, affirming Bear’s sentiment. I was bored anyways, and the thought of getting to cross the old suspension bridge and exploring the other side of the lake was enticing. Plus, like I said, I still liked Rusty at this point, and was eager to impress him, the way younger boys are with the older boys. So I got up and began heading for the bridge. He waved me off. “Nah, gotta get some stuff first,” he said. “Be prepared and all.” So I trailed after him as he marched around the corner of the cooking tent… and right into Roger.

Rust was all tall and awkward and still doing the whole puberty thing, zits and voice and all. Roger, in contrast, was short, like his dad, but he hadn’t so much hit puberty as just slowly got older. The boy would have been the spitting image of his father, but younger, if only the older man had been a good fifty pounds lighter. Roger was handsome; Campbell merely had been. Both had this keen, intense gaze magnified by hazel eyes and highlighted with strong eyebrows, and when I caught sight of him, Roger looked straight at me with those eyes. I remember the gaze, but it didn’t affect me the way it did some of the younger boys. I could stare back just as much as he could.

Roger had his dad’s walking stick. It must have been expensive.

I was certain he wasn’t supposed to have it.

“Let’s go hiking,” he said, and I grinned, excited by our little rebellion.

The suspension bridge wasn’t that big, maybe fifty feet long, all chains and wire mesh. Covered in icy rime, we’d discovered the night before that we could slide down to the sagging middle on our hiking boots. It had been fun until some guy from another troop saw what we were doing and told. Apparently, despite the sides running up to our armpits, some adults were afraid we’d somehow fall. We weren’t, of course. We knew what we were doing. We were careful. The adults were just killjoys. Especially Campbell, who’d shouted something about not wanting to have to go to court when one of us drowned an icy death. Dad didn’t want to put up with it, so he’d raised his hands in defeat and let Campbell get his way.

No one was watching, so we tried to slide, but the ice had begun to melt, and it wasn’t as fun as it had been the night before. We marched across, disappointed, but not bitter, but that was fine, because what we really wanted was the isolation of the other side. We’d come from the camps, a massive, flat area, surrounded by forest. Crossing the lake put us square in the forests, where no one ever went. The black powder rifles, the tomahawk throws, the trading, all the structured activities were back in the camps.

The sound of the camp faded away the further we got into the trees. The wildlife, what little there was, silenced itself at our presence. Coming to a fork in the road, we started quibbling about which way to go. Roger didn’t indicate a preference. Rusty wanted to go around the lake, where we could see the camp, and the camp could see us. I wanted to head back in the woods. The appeal of unexplored territory, coupled with the worry that the adults would see us and demand we return, fresh in my mind.

“Don’t make me pull rank,” Rusty said.

“What does that mean?”

“It means that I outrank you, so I can tell you what to do if I want, and you should be grateful I don’t do it more often.”

“When I’m in charge,” I replied solemnly, “I won’t pull rank on anybody.”

“Yes you will, you’ll see.” Roger hadn’t said much the entire hike, so we both snapped our heads to look at him. He jammed his father’s hiking staff into the ground, gloved fingers tracing the carvings on it. I couldn’t really tell what had been carved into it, maybe a bear or a wolf or something. The only thing impressive to me had been the hints at its price tag.

I crossed my arms. “No. I won’t.”

We followed Rusty’s path, silent for a while. When Roger finally spoke, it stopped me cold. “You’re only in charge because your dad’s the scoutmaster,” Roger muttered. I whirled on him, surprising him as much as me. I wasn’t angry. I’d been expecting someone to say this. “My dad? Are you sure? My dad? The guy who always chooses to work with other kids if he gets the chance? The one who always demands extra work from me? My dad? The one who pushes me harder than any of you so he doesn’t even have the appearance of special treatment?”

I was proud of my dad for it. Struck me as a kind of integrity.

Roger had received two votes to my twenty.

“I earned it, Roger.”

We were silent. Rusty thought better of his plan to march in full view of the campers, and took us around the back way. Soon, the jokes were flowing, and we were laughing about the stupid things that teenage boys laugh about, the ‘what-if’s’ and ‘have you seens’ and other things that seemed so vital then and so cringe-worthy now. Things were going well, and then Rusty found a sturdy stick, the kind of thing you’d make a hiking staff from. “Let’s fight!” he suggested, excitedly.

Roger slammed his father’s staff into the ground, as if making a decree. “No, let’s wrestle.” Rusty shrugged, tossing his stick aside. Roger set the staff down gently. They wrestled for a moment. Rusty was taller, but Roger was bigger, and it quickly became clear, to me, at least, that Rusty was going to lose, or at least tire more quickly. Roger had him beat, and he knew it, so when he had the chance, and Roger charged him, Rusty sidestepped, so Roger ran straight into me.

I tried to get out of the way, but Roger hit me, tripped, and fell to the ground. I remained standing.

“You’re lucky.”

“Nah,” I said, with mock confidence, “you can’t knock me over is all.”

“Can too.”

Truth was, I didn’t want to hurt Roger, but the adrenaline was flowing, and I was tired of this. Tired of the weeks of being told my victory was unearned. Tired of hearing how Roger was the better choice to lead. Tired of being made to feel like a loser when I didn’t.”

“You think you’re better than me, Roger?”

Something in his demeanor changed, and he screamed, loud and animal, as if he’d been waiting to scream every day of his life. When he came, I took him with my shoulder, driving him to the ground. I’d had kids try to fight me before, but usually, they were the hyperactive ones, the kids who got in trouble ‘cause their dads weren’t around or ‘cause their dads didn’t care what they did. I put Roger down and held him there and stared in his hazel eyes and waited for the fire in them to die down. Then I let him go, making the mistake of thinking they had.

He screamed and charged me again, leaping this time, hoping to use the force of his momentum to bring me to the ground. I caught him instead, used his momentum against him, let it turn us around, and flung him into a patch of snow that hadn’t quite melted. He rose, sputtering, but he looked okay, so I sighed, relieved I hadn’t hurt him.

This time, he reached for his father’s staff.

“What, can’t beat me on your own?”

The taunt surprised me. I’d never taunted anyone before, but something about Roger was rubbing me the wrong way, something that begged for a taunting. Something in me wanted to scream “you’re not better than me,” a reply to an unspoken claim. Instead, I stood there, waiting for him to swing. Rusty intervened. He’d wanted a staff fight, and now he had one. Rusty swung and Roger, and Roger fought back, getting angrier with each swing. The aggression in his assault pushed Rusty back against some brambles. Whenever he could, he looked at me, like he wished we were the ones fighting.

Then Roger screamed again, and swung his staff so hard it broke.

We were silent for a few seconds.

I don’t remember going back. I remember being afraid. I remember how meek Roger became. We traipsed through the woods, shuffled across the bridge, and walked up to camp. I didn’t hang around to hear what happened next; by the time Campbell started screaming, I was far enough away that I only heard the muffled susurrus of his distant voice. The Roger I saw later was meek. Quiet. Businesslike when he had to be. He didn’t hang out with the other guys as much; instead, he was always off to the side. He started acting like his father, and I finally realized what that meant. Campbell had obliterated his son. All he left was another Campbell.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Short Story #1

I had to write a short story for. My teacher was all “ooh, ahhhh” in class, then gave me a B because he wanted me to describe the entire details of a preflight check. Anywho, since it’s graded, here you go.

As she drove to the airport, she thought about Michael, who was dead. His death had been completely avoidable, but it had happened, and Dad had dragged her off to attend his funeral, and she was thinking about it, even now, on the way to the airport. She’d met Michael only once, and that was when he won the flying scholarship, because of course he won the flying scholarship; he was the rich kid at the richest school, the kid engineered by his parents for diplomacy and success. He’d paid them back by killing himself and his father.

Hundreds attended his funeral. Wept. Hugged. Nobody talked about how stupid he’d been, about how he’d still be alive if he’d just paid attention to his altimeter, about how he shouldn’t have been flying in IFR rules when he hadn’t had the proper training. Michael, the rich kid with good looks who’d been bred for success, didn’t deserve to win that scholarship. But he did, and she’d taken second place, and now, here she was, zooming down a dirt road past the county garbage dump on her way to another kind of airport.

Broadside was owned by Jim, a man of indeterminate age who didn’t give a shit about anyone or anything, unless that anyone was a fellow pilot, and that anything was an airplane. Or beer. Jim’s Cessna 150 was a piece of shit, and he knew it, but he didn’t care. It flew, and that was all that mattered. People kept their aircraft at Broadside because it was cheap and Jim didn’t ask questions. At Midtown, the FAA might drop by the FBO, or the Air Force might want to get some fuel. Nobody ever visited Broadside unless they had to. It sat next to the garbage dump, after all.

She parked Dad’s civic and clenched her fists and swore at him in a wordless swear. He’d insisted they go to Michael’s funeral, even though they’d only met once, and Michael had won the scholarship even though he didn’t need it, and then he’d spoiled it all by crashing like an idiot. Most crashes are pilot error, she’d been told, but she had a hard time believing it, not with Jim’s Cessna 150 sitting over there under the aging concrete.

She’d soloed last week.

She’d soloed last week, and on takeoff, the door had come open, and takeoff is the most dangerous part of a flight, and she’d stupidly shut it when she was supposed to have her hand on the throttle and stick. When she landed, Doug, ruddy-faced and a hundred pounds overweight since all his football player’s muscle had turn to fat in the thirty years since college, charged over like a linebacker, looking ready to scream. Doug was the kind of man who was too big to fit in a Cessna 150, and that was readily apparent, even as she tossed her headset into the instructor’s seat and ripped the belt off and shoved the door open and blurted out “I’MSORRYTHEDOOROPENEDONTAKEOFFANDIDIDN’TKNOWWHATTODO.”

All the animus drained from Doug’s face. “Oh,” he said, “yeah, that happens. I thought you were going to die.” But she hadn’t. She’d kept her cool and only panicked when she saw Doug’s angry face. “Do it again,” he’d said. “This time without the door opening on you.” She grinned, and she did, and she knew, even then, that she’d been meant to fly.

Now, Doug’s car was missing, but that was alright. Her instructor was always late, and he trusted her to do all the pre-flight stuff herself. Doug was a good man, when he wasn’t still asking her if she was certain she couldn’t afford to fly in the 172 instead. Unfortunately, she could only afford the 150. Working $5.85 an hour meant certain restrictions, and this was one of them. It wasn’t like she’d won a scholarship and got off easy. She told herself that it was a good thing, that working to fly on her own dime meant taking it more seriously than Michael had, but she had to admit, in the brief time she’d spent in a 172, she wished she could have afforded one.

Doug’s bulk meant the 150 sagged on takeoff, like a too-fat goose. Jim’s poor care meant that, occasionally, Very Bad Things would happen. One night, the electronics went out. No lights, no instruments. She’d started panicking until Doug told her it would be alright, that they’d navigate using the city lights to get home. Even then, she’d worried about how they’d land without a radio, but they had, and everything was fine, and Doug gave Jim a talking to.

The next time something broke, it was the oil, smearing the windscreen. That happened twice. Doors opening in mid-air happened more frequently than it should, but Doug never seemed terribly concerned. She suspected he didn’t care until she realized that he was just as scared as she was, but with enough experience to know to keep a level head.

By the time she finished the preflight check, Doug still hadn’t arrived. Broadside’s terminal was the only real building around; it didn’t even have a hangar—the planes sat under concrete pylons and corrugated steel. The 150 needed fuel, and she needed to pee, so off she stomped, across the straw-like grass that never changed color, picking up nettles as she went. Stopping outside the terminal, she picked them off, straightened herself up, and stepped inside.

Jim sat, in his coveralls, browsing an old Trade-A-Plane, flipping through its yellow pages slowly. He tossed it into the disheveled pile next to him and lifted another from the stack. “Hullo,” he nodded, then looked at one of The Guys, who set down his beer and got up to half-heartedly stir the popcorn. The Guys were friends, or maybe groupies, though she had no idea why Jim would have groupies, unless being an airport owner was enough. They sat around in silence most of the time, but when they talked, it was about who was selling what airplane and what they’d like to buy. She had the impression most of the old buzzards hadn’t flown in years; those who did were younger men in their thirties and fifties.

“D’ya want some soda?” asked one of them, gesturing to the photo-covered mini fridge. “Nah,” she shrugged, and stepped over a bundle of tied-up magazines on her way to the terminal’s only restroom. It was a men’s restroom, all yellowed walls and bare-bones and equipped with a urinal. The rest of the building’s interior—what wasn’t covered with smoked glass, at least—was a sky blue, at least when the lights were on, but most of the time, they were off, because the sun was bright enough to keep the terminal dimly lit.

She stepped back out into the room and asked if anyone had seen Doug. No one had. She checked her flip phone. Yup, still Thursday, now 6:37 P.M. Still no Doug. “We fueled up the 150,” said one of The Guys, nodding to the truck that was now parked conspicuously close to the building. “It’s good to go.”

“Thanks.”

“You soloed?”

“Yup!” She beamed, but tried to look casual. It didn’t work. The one asking smiled a knowing grin.

“It’s okay to be proud of yourself.”

Her phone rang. No one so much as looked up. It was Doug, so she stepped outside to take the call. “I won’t be able to make it,” he said, “not for a while, so I want you to fly some circuits by yourself. You’ll be okay, right?”

Michael had died two weeks ago.

“Yeah, I’ll be okay,” she lied, until the confidence bubbled up from her stomach into her brain and she knew, with absolute confidence, that she could do it. Michael had died because he was stupid. Because he was flying at night, because he might have been a little tipsy, because he wasn’t paying attention to his altimeter. She knew, right then and there, that she was no Michael, and that she could fly a circuit, but she still wished Doug was there to see it.

Still, she was a bit nervous, so she checked the plane out one more time. She tested the lights she wouldn’t need—not while it was so bright out—and tightened the oil once again, just to be sure it wouldn’t leak. When she finally sat in the cockpit, ready to roll, she checked, double-checked, and triple-checked both doors. Then she started it up, taxied out to the runway, checked the doors one last time, and sat there.

Then she called it on the radio, lined up, and took off. It was so smooth, especially without Doug inside. On her solo, she’d been surprised to discover how nimble the 150 could be, but she was ready this time. It soared. Takeoff was smooth, the sky was clear, everything was perfect… until the eagle showed up.

There it was, directly in front of her. A bald eagle. Regal, proud, gorgeous, and approaching at around a hundred and fifty miles an hour. Uh oh. She banked. Didn’t panic. It felt like minutes as she zoomed past, staring at the window, looking across, then down, then behind at the Eagle, its wingtips outstretched. How many people had ever seen an eagle in flight from above? She snapped back to attention, but the rest of the flight was uneventful. She completed the circuit and landed, still thinking about the bird. She taxied back, and burst out laughing.

Doug answered on the first ring, but said he wouldn’t make it before she had a chance to tell him. She decided she didn’t want to. On the way home, down the dirt road, past the dump, she kept thinking about it, playing the image over in her mind. For the first time in weeks, the image of a grounded pilot in a casket left her mind. The only image she saw now was of the eagle.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Riverside

It’s safe to say that Tom didn’t care if we lived or died. I think the only thing he really cared about was freedom, and that was great, because Tom owned an airport, and if there’s anything more free than flying, I’ve never encountered it. I knew Tom because of his airport, Riverside, though it sat closer to the county dump than the river, and, if I’m being honest, it was more of a dump than an airport too. Of course, that was the way Tom liked it. It was the cheapest airport in the city; you came here if you were poor or desperate but still wanted to fly, which is why I’d come. Riverside wasn’t much, just a single runway. Even the planes were stored outside, underneath some weird concrete structures I still haven’t got a name for. The hangars themselves could have been confused for storage sheds, they were so small. But Tom? Tom was king of this domain, and he was proud of it, even the little old Cessna 150 that was so poorly maintained it nearly killed us more than once. Tom didn’t care.

I didn’t know him long, maybe a year at most. I couldn’t afford flying lessons anywhere else, so I drove up in my parents’ beat-up old Civic every week, cash in hand to pay Tom for an hour of his 150’s time and my instructor, Dale, for an hour of his instruction. I’d show up, and Tom would look up suspiciously, like he didn’t remember me, until one day, he finally did, and he had the plane ready and waiting to go. I don’t think he paid me any mind until he was sure I took my lessons seriously. Tom was mean, not mean-spirited, but mean like a badger. Tough. Old. He’d lived a good, long life, and he didn’t care about anything anymore, unless it was architecture or flying. I used to think if Death came for Tom, the old badger would look up at Death, grunt, and go back to his magazines.

Well, Death came for Tom five years ago, and I only just found out, so this is a eulogy for a man I barely knew, but a man I had some affection for, even if it was more of a bemused tolerance than anything else.

You’d find Tom in the terminal building, which was really more of a single room with a bathroom attached, and calling it a bathroom is being generous. Tom and the other old buzzards would lounge around, reading old Trade-A-Plane magazines and talking about years gone by, occasionally getting up to put some butter on the popcorn popper, which smelled like it’d burned popcorn one too many times, and probably had. Tom was an architect by trade, and what wasn’t covered in decades of airplane classifieds was covered in blueprints.

Tom made me nervous for the longest time. He’d test me with his questions, asking me what kind of plane had this or that engine, the callsigns for various airports, that sort of things. His friends would join in from time to time with the bemusement that’s unique to old men and pose their own aviation-related questions. Most of the time, I had an answer, and that made them happy, but even when I was answering, I still felt embarrassed and a little scared each time. Dale’s arrival was always a relief, because he was in his late-50s and still remembered what it was like to be a boy who wanted nothing more to fly.

Things changed. The old buzzards were tickled pink that a boy loved aviation as much as they had, and it got to the point where they’d start fueling up the 150 without me asking, using Riverside’s sole gas truck, which was so ancient that it sported more rust than paint. I’d trudge through the nettles and straw-yellow grass each week, ready to fly, and they’d be there, amused by this boy who wanted nothing more than to fly.

Tom couldn’t fly anymore. He said he couldn’t be assed to get his medical, but I think deep down, he knew he wouldn’t qualify, and he didn’t want to face that fact. But that’s just a guess.

Once, I saw Tom wearing a hat that said “#1 Grandpa,” and I assumed it was ironic, because Tom didn’t seem like a grandpa at all. He was old, sure, but he had none of the grandfatherly qualities I’d come to expect in men his age. Tom had worked--and worked hard--his whole life, and now it was clear he was done working. Riverside was his retirement, his hobby, his escape. He liked airplanes. He lived ‘em. Probably would have lived at Riverside if he could have. Once, Tom told me that he had a particularly rare airplane, one I’d been wanting to see my whole life, and I listened, wide-eyed, as he told me all about her. I couldn’t believe it was true. Even now, I’m not sure if it was. I never could read Tom.

He passed away five years ago, and I don’t know what of or why. All I know is, within a year, the family sold Riverside to a rich car salesman, and after a couple years of promises about how he was going to keep Riverside an airport, he sold it to Cornejo and Sons, and the latest plans for Riverside are to turn it into a mine. Maybe it already is. I don’t know.

When the doctors told me I couldn’t fly anymore, I didn’t want to be near an airplane, not with clipped wings like mine. I pushed Riverside, and Tom, and Dale, and all the rest, out of my memory. But some memories never leave. I remember almost killing a bald eagle on takeoff in Tom’s 150. I remember the power going out at night as Dale and I flew over Wichita, flying our way home by the city’s landmarks. I remember the gruff laughter of old men who loved flying. I remember Tom, and I think I want to run an airport like Riverside one day.

Done for school last week.

1 note

·

View note

Note

You have a heart of gold. Don't let them take it from you.

Thanks. I love you too.

0 notes

Note

Hi there I have really liked your writeing and i have to ask when you wrote for Kotaku in the article "Fallout 3 Isn't Really An RPG" I began to wonder when you brought up that new Vegas is more like an RPG. while 3 did not fallow that formula so in your opinion what formula will Fallout 4 follow?

Fallout 4 will probably be more like the other Bethesda games, yes.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I Am An Actual Carnivore

Objectively speaking, the world would be better off if humanity resorted to being vegetarians. Fewer animals would die, which is nice. We wouldn’t have to deal with the stinky butt smell of cattle near the slaughterhouses. Overall weight concerns would diminish (though, really, that’s more of a wheat problem). Pollution would go down tremendously. As I said, the world would be better off. Unfortunately, there’s a problem.

(caption is here so it doesn’t show up in the autotweet of this post; my arms are stupid thin and pale because I can’t get out much and I can’t work out much either)

Humans are omnivores--that is, they can eat both plants and animals. You’ve also got herbivores, which eat plants, and carnivores, which eat animals. Like, hey, humans can eat chocolate and grapes, but dogs can’t. Dogs are carnivores.* There’s a lot that goes into this, from teeth to stomach to GI tract to even cellular details, but the simple fact is that carnivores need meat to survive.

You’ve probably heard people who relish the thought of devouring meat describe themselves as carnivores, but it’s important to understand that they’re really just omnivores (they can eat both things) with a preference for meat. Humans can go either way.

And then there’s me.

Those of you who know me know about my health struggles. You know I can get a bit irritating on social media when I’m feeling particularly bad, and it sucks that I feel as bad as I do as often as I do. That’s the problem with being so poor you can’t afford to treat the health problems so you are healthy enough to get work to afford the money to pay for the treatments (go go circular health problems!).

What you might not know is that I’ve been through some pretty extensive genetic testing, and a relative just went through some of his own, and passed it on to me, because we have a similar genetic profile. He has been diagnosed with a problem, we share the same genes that cause this problem, and therefore, I feel comfortable in making the claim in the title of this piece, which I’ll get to in a bit.

So, for those of you who don’t know, or would like a refresher: I suffer from a host of issues that come from various genetic mutations. The First Main Problem is that my body doesn’t absorb the nutrients it needs in order to properly function--chief of which is absorbing magnesium (which is important for muscle function) and zinc. My body doesn’t create enough serotonin or dopamine either. For a while there, my thyroid was failing, but treatments actually got that one back on track, which is nice.

My pain issues stem from this.

The Second Main Problem is that my body’s Krebs Cycle does not function properly. This is a problem, because a properly functioning cycle is how the body makes energy.

My fatigue issues stem from this.

(this is a picture of KU Med Center I took the last time I was there)

The thing about the Krebs Cycle (or citric acid cycle--I like Krebs because it sounds more proper nouny, and that’s what it was called by the doctor who discovered I had problems with it) is that it takes all those lipids, carbohydrates, and proteins you eat and transforms them into energy.

One thing I’ve said over the years is that I feel sick when I go without eating meat for too long. It would be nice to subsist on a diet of various flavored rice and noodle dishes, but I get very sick if I eat them too long, and I definitely get sick if I go without eating meat for a period of time.

Most people I’ve spoken with laugh this off. Nobody needs to eat meat, right? I do. I start feeling weak, unfocused, even confused. I get to the point where I can barely stand. Depression hits me so hard I want to die. When I eat meat, the problem goes away. My parents have only recently come to understand that this is A Real Thing. My symptoms manifest--or get worse--when I don’t get enough meat to eat.

But... we never really thought about this or discussed it with anyone. It was just accepted as an element of my illness.

That’s when this one family member found out about his genes. Basically, he’s got a genetic mutation that means his body’s Krebs Cycle doesn’t process carbs. Fats? Sure. Proteins? Absolutely. Carbs? No can do, amigo. His doctor recommended he get more meat in his diet, and, whaddya know, he’s healthier now than he’s been in a while.

Turns out I have those same genes.

My body isn’t processing the nutrients I get when I eat my veggies--it’s why I can eat tons of magnesium-rich foods and not get any benefit. The magnesium must be directly injected in my bloodstream for it to work.

Now it turns out that my body doesn’t really do the whole carb thing.

If that weren’t enough, celiac runs in the family, and while I don’t have celiac, I do have a couple of the genes that, as I understand it, indicate a predilection for celiac.

So... basically, what I’m saying is... plants don’t give me the nutrients they should, which sucks, because I love eating them (especially fruit, rice, potatoes, and lettuce). Meat, however, enables me to function--my citric acid cycle can still process fats and proteins.

For now, I’m putting an emphasis on meat, eggs, and beans. It ain’t ideal, but I feel a lot better than I did when I was trying to live off rice.

Only problem?

I’m dirt poor. Food stamps end in September unless I can get an extension.

I can’t afford meat.

If I can figure that out, I’ll be good as gravy until I can afford and receive proper medical treatment.

I’m a carnivore.

And that’s kinda cool.

*if you know anyone trying to force their dog to eat vegan/vegetarian, just know that’s animal abuse, and do what you can to ensure the dog is given proper access to the nutrients it needs.

1 note

·

View note

Text

“You’ll never fly again”

I’m sitting here waiting for the other students to finish their essays. It’s my final semester. I’m polishing things up, getting to the credits I missed. The teacher gave us a brief writing assignment to get an idea where we are, skill-wise. Here’s what I wrote. Yes, it’s a true story. Me, five years ago.

“You will never fly again,” she says, and in the moment, I feel numb. I don’t think it’s even registered with my mom, who sits there and tries to think her way out of it, as she always does. Dr. Bischoff remains the consummate professional, but in the moment, professionalism is the last thing I need. I do my best to stay calm, but inside my head, my mind is racing.

We leave the hospital and head for the car.

This is not how it was supposed to be.

My oldest memory, and one of my most cherished, springs to mind. I am standing in a field. Fighter jets roar overhead, and I have no concept of what that means. All I know is that they are very loud, they are very fast, and people ride them. I stand, elbows stretched out, tiny hands pressed tightly to my ears, feeling the roar of their engines pulsing through my body, and I resolve, in the only way a toddler can, to be a fighter pilot one day.

Memories come faster, jumbled up in roughly chronological order. I remember the little video I watched growing up, the one with children singing about the Wild Blue Yonder while the Thunderbirds--the same jets I’d seen as a toddler--zoom overhead. One kid fantasizes about being a pilot. Watching the video, so do I.

In the car, I tell mom I’m tired--waking up so early in the morning to drive all the way to Kansas City had wiped me out, and my health wasn’t helping. I don’t dare tell her the real reason I need to lie down. I am so emotionally devastated, I barely have the strength to sit, let alone stand. Mom tells me I’ll get better, but by this point, I’ve been struggling for five years. I dropped out of school two years ago.

I was meant to fly.

Every flight instructor I’d ever had, from the test pilot with the steel grip to the giant whose girth meant we had to race down the runway just that much longer to get airborne to the scrawny kid who couldn’t understand the phrase “I don’t have texting” all said the same thing: I was a natural. Kirby the test pilot once revealed, after a particularly rough landing, that I’d just made an expert landing in crosswinds that would have scared normal pilots. It would have scared me, had I known. It didn’t scare him. Nothing could. He was a test pilot.

I’m scared now, and when mom pulls up to get gas, I bury my head in the pillow I’d brought with me and I start sobbing the biggest, hottest tears of my entire life. “You’ll never fly again” I hear in my head, over and over and over again. She’d said later that there was a chance, that I’d need treatments I couldn’t afford and if I was lucky, then maybe, just maybe, I might fly, but I couldn’t do it professionally.

I’d been scared before. After my first solo circuit, Doug raced over, face red, fists clenched. He was huge, and he looked like he was about to let loose on me in a way he’d never done before. Before he could say a word, I popped the door, almost to the point of tears, and told him the door had come open on takeoff. His visage changed in an instant. “Oh,” he said, “right. Yeah. That happens. Glad you didn’t crash. I want you to try again. Hopefully it won’t fall apart on you this time.”

It was a crappy little Cessna 150 that had, among other things, sprayed oil all over the windshield, completely lost electrics in the middle of the night, and yes, had a penchant for popping open its doors while flying. You couldn’t have asked for a worse plane, but in the moment, I’m lying in the back of my car, and the only thing I can think about is getting back in that plane, taking the stick, and flying again.

“You’ll never fly again,” and deep down within me, I know it’s true.

I’m done.

I’m finished.

There is nothing left. I won’t be a professional pilot. I won’t see the world. This morning, I thought I had a future. I have been disabused of that notion. Mom comes back, tries to comfort me, finally realizes it won’t help. Gives up. My mind repeats those words, over and over and over until I fall asleep: “You’ll never fly again.”

I want to die.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

ArtStation - Mad Max Fury Road Tribute, by Chun Lo

More Characters here.

More about Mad Max here.

2K notes

·

View notes