私の日本語の勉強ブログ。楽しんでください!21 | Native English speaker | Let’s talk and study !

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

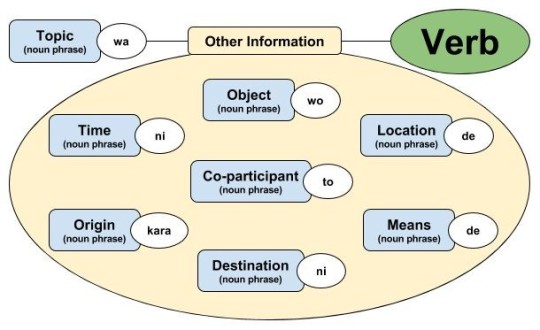

11.5) The に Particle [Part 1]

While が is the most important particle in Japanese, に may hold the title for being the most versatile. It has A LOT of uses. But fear not true believer, I have a post (or a few) to help you understand the many uses of に!

Let’s start out slow, shall we? In this post, I only have 2 uses to tell you about, marking existence and marking movement. The interesting thing is that you may not see the connection at first, but it’s there (at least in a Japanese way of thinking). Because I have so many examples for you, the vocabulary for this post won’t contain the verbs; I’ll put all of them together a little later in the post.

【Existence】

に is used to mark a place of existence. Back in this post about the particle の, we talked about “Location Noun Phrases.” These are nouns connected to location nouns (such as 上, 下, 外 etc.) with the particle の. Even though my examples there only used the location noun phrases as topics, they are more often used to say where someone or something is located.

For example, the English phrase “on the table” would become 机の上 in Japanese. If we want to make a comment about that location, we attach the は particle. However, if we want to say that something is located there, we need the に particle. If we wanted to say that a cat is located there, we would say:

①{机の上に}猫が{いる}。

= At the on of the desk, a cat exists.

= There is a cat on the desk.

いる is used because the subject (the cat) has a will of its own. For non-living things (and plants) that don’t have a will of their own, ある is used. A more extract example would be:

②{宇宙には}無数の星が{ある}。

= As for in space, an uncountable number of stars exist.

= There are countless stars in space.

It’s the same idea. が marks the subject of the sentence while ある or いる tells us that it exists and に tells us where. Example 2 additionally made the place the topic. This leads to the nuance that we are talking about things that exist in the universe.

③ それは{ここに}{ない}。

As for that, it isn’t here.

④ なぜ橋本さんは{家に}{いなかった}の?

Why wasn’t Mr. / Ms. Hashimoto at home?

As you can see, the same is true when you want to talk about things / people that are not located somewhere. Note that the は particle is often used in sentences with negative verbs like ない or いなかった.

【Destination of Movement】

The remaining uses of に all have a common connection, which is movement. The first time Japanese learners are introduced to に, it’s usually in sentences where there is some form of movement. In these simple sentences, に marks the destination. Here are some examples:

⑤ 3年前、{アメリカに}{行った}。

= 3 years ago, to America (I) went.

⑥ {ここに}{来て}ね。

= To here, come, won’t you?

⑦ 仕事の後、彼は{帰る}。*

= After work, as for him, he went / came home.

⑧ これから授業に{出る}。*

= Now, I will leave (where I’m at) to go to class.

⑨ お風呂に{入りたい}。

= Into the bath / tub I want to go.

*In example 7, 帰る simply means the subject is returning home, we don’t know whether the listener is at home or not. In example 8, the に bundle marks the destination. If you want to state the origin point, you would use から.

【The Result of Moving Yourself】

Now here is the interesting part that will tie movement and existence together. In Japanese, the idea of existing somewhere is not limited to the verbs ある and いる. There are a lot of other verbs that express existence - it’s just that the existence is a result of some kind of movement. Take a look at this example:

⑩ 友達が{空港に}{着いた}。

= My friend at the airport arrived.

= My friend arrived at the airport.

Let’s say a 4-year old asks you, “What’s the difference between arriving somewhere and being somewhere?” First off, that child is very smart. But when you actually think about it, the idea of arriving somewhere is not really different from existing there. (I think the difference is that “arriving” carries with it the idea that there was some travel or movement prior whereas simply existing somewhere doesn’t tell us how the person got to that point.)

With that in mind, the following examples also show us the result of some kind of movement. Notice how に marks where the subject ends up after the movement.

⑪ {バスに}{乗った}。

= I got on the bus.

(movement onto the bus and then existing there)

⑫ トムは{その椅子に}{座る}。

= Tom sits in that chair.

(movement to the chair and then existing there. More simply, sitting there)

⑬ {ドアの枠に}{立った}。

= I stood under the door frame.

(movement to under the door frame and then existing there. Simply put, standing there)

【The Result of Moving Something】

Our next set of examples are closely related to the last section’s examples with one difference: Now instead of a person moving, an object is moved and then exists somewhere. Because this implies that the object has no volition of its own, our old friend the を particle will show up.

Here are some examples where the end result of some kind of movement is existence somewhere else:

⑭ 寝る前、猫を{外に}{出してください}。*

= Before you go to sleep, please put the cat outside.

⑮ 彼は{カメラに}新しいフィルムを{入れた}。

= He put new film into the camera.

⑯ 鉛筆を{机の上に}{置いた}。

= I put the pencil on the table.

⑰ 彼女はミルクを{ボールに}{注いだ}。

= She poured milk into the bowl.

⑱ つけめんは、麺を{スープの中に}{付ける}。*

= As for Tsukemen, (you) the noodles into the soup dip.

⑲ {肉に}塩を{かけよう}。*

= I’m going to put (sprinkle) salt on the meat.

*In Example 14, though the cat is alive and would normally have volition to do something, in this case it is treated like an object. Poor cat! In example 18, even though dipping is for a second or less, the noodles will exist in the soup for that short period of time. In example 19, かける has the image of showering something completely over something else. 肉に would then mean that the meat will exist inside the “shower of salt”. 🙃

【Clothing】

There are a whole set of verbs that have to do with putting on and wearing clothes, accessories, footwear, etc. I’m planning on writing a separate post about them but for now, it’s good to realize that they all fall into the category of moving something in order to make it exist somewhere - that is, on a part of the body. With these verbs, if there is a に it will be attached to the body part because that is the “destination” for the article of clothing. Most of the time though, this に bundle is omitted because it’s obvious from the verb and the article of clothing.

⑳ 父は(頭に)帽子を{被る}

= As for my father, he hats wears.

My father wears hats (on his head). (duh lol)

【The Verbs】

The に that marks the location of existence works together with only certain verbs. It would be very strange to say 家に食べる。The reason is that 食べる is not the correct kind of verb that works with に. Here are the verbs we have seen so far:

I do want to mention something that you will inevitably run into. Using these verbs in the past tense obviously describes a past action. Using them in the non-past (dictionary) form can either indicate a future action or a habitual action.

However something interesting happens when you change these verbs to their て form and then attach いる. Again, I plan to go into more detail at a later date, but there are 3 possibilities:

A) You will end up describing a continuous, ongoing physical action.

B) You will end up with not an ongoing action, but an ongoing state or condition.

C) Depending on context, it could be case A or case B.

Here are some examples:

出している means continuously putting out or giving off something.

行っている does not mean “continuously going”. It means “went and then remained in that state”, more simply “is there”. It’s the same with 来ている.

乗っている can mean getting on / boarding but it can also mean boarded and then remained in that state, more simply, is on the bus, train, etc.

座っている means sat and then remained in that state = is sitting

【Conclusion】

Well that was a lot, wasn’t it!? I gave you a lot of examples but I hope it’s easy to see how they all are related. Whether there was some sort of movement (moving yourself or moving an object) or not, the end result is always existence. I think this is the key to understanding the に particle because it always marks the location of the existence. If you keep this in mind, you won’t end up asking yourself “why do they use に HERE?” all the time. No one needs all that!

As always thanks for your time and see you next post!

Rice & Peace,

– AL (アル)

👋🏾

295 notes

·

View notes

Text

Basic Verbs (1): Korean & Japanese

보다 - 見る (みる) - to see; to look at

듣다 - 聞く(きく) - to listen, to hear

먹다 - 食べる (たべる) - to eat

마시다 - 飲む (のむ) - to drink

하다 - する - to do

오다 - 来る (くる) - to come

가다 - 行く (いく) - to go

공부하다 - 勉強する (べんきょうする) - to study

자다 - 寝る (ねる) - to sleep

만나다 - 会う (あう) - to meet

말하다 - 話す (はなす) - to speak

주다 - あげる - to give

읽다 - 読む (よむ) - to read

사다 - 買う (かう) - to buy

만들다 - 作る (つくる) - to make

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

Japanese lesson 85

Today's theme is "pretty much".

今日のテーマは「ほとんど/だいたい」です。

(きょうのてーまは ほとんど だいたい です)

1. I have pretty much finished my homework.

宿題ほとんど終わった

(しゅくだい ほとんど おわった)

2. That's pretty much it.

だいたいそんなところだよ。

3. I eat pretty much anything.

だいたい何でも食べれるよ。

(だいたい なんでも たべれるよ)

A: Have you finished your homework yet?

宿題もう終わった?

(しゅくだい もうおわった)

B: Yeah, pretty much.

だいたいね。

You should use it!

See you again!!

296 notes

·

View notes

Text

227 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 Month Grammar Challenge Day 25 - ~につれて, ~にしたがって, ~に伴って

Day 25 - Three things with similar meanings but slightly different usages - must be another N2 grammar post! (One example each because otherwise this one will not get done.)

~につれて 名する���動 辞書形 + につれて “As; in proportion to; with; following; in accordance with” As one thing changes, another thing also changes in proportion with it. The change only happens in one direction and is a natural change, not a wilful action. につれ is the more formal form used in writing.

例)年を取るにつれて体が凝ってなっていく。

~にしたがって 名する・動 辞書形 + にしたがって “As; in proportion to; with; following; in accordance with” As above, it shows a proportional change. However, this change can go in more than one direction and often shows a natural change. This is used in writing more than につれて.

例)山を登るにしたがって気温が低くなる。

~に伴って (ともなって) 名する・動 辞書形 + に伴って, 名する + に伴う + 名 “As; in proportion to; with; along with; at the same time” One change accompanies another change. This is used for large scale changes, not personal matters. It has a formal, written feel.

例)人口が増えるに伴って、食糧を配達することは問題になる。

91 notes

·

View notes

Photo

もったいない|What a waste!

“Mottainai” usually has a feeling of regret for whatever was lost. If you’re painting and you accidentally got a ton of pink color on your palate that you can’t use, then mottainai. If your girlfriend paid for a cup of coffee and threw it out after drinking half, then mottainai. Anything that could have been useful but you’ve lost for some reason is mottainai.

462 notes

·

View notes

Link

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

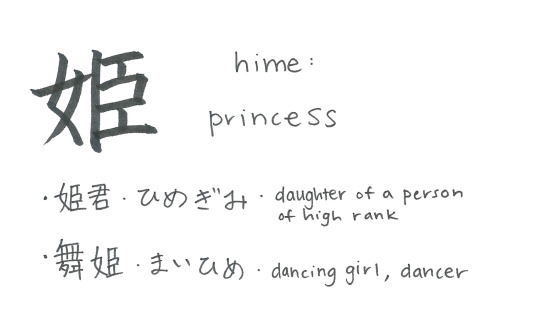

1220/2000

JLPT: N1

School Grade: Junior high school

This character has a somewhat obscure origin. Older forms show that it was written as a combination of 女 woman and 𦣝 an obscure component that was associated with the emperor Huangdi. 𦣝 was used phonetically to express the name of the river where emperor Huangdi was believed to be born. 姫 originally referred to women of the Huangdi line. Later, 姫 came to mean “princess / noble lady” in general. One theory even says that there were many beautiful descendants of this line, so 姫 came to have an association with beautiful women.

The current form is written as a combination of 女 woman and 臣 staring eye/retainer. This may have occurred due to an assumption that 姫 was meant to refer to a woman who is guarded or protected.

228 notes

·

View notes

Text

Difference Between ~と言う and ~と言っている

I’ve always read them but never knew understood how to use them. Same with と思います and と思っています, which I will also cover in this post.

~と言う (to iu) is the form you use to directly or indirectly quote what someone has said. と is a quotation marker that can also be used with other verbs like 聞く (to hear)、伝える (to convey)、思う (to think), etc. 言う means to say.

~と言う

places emphasis on the fact the person said something rather than the content of what she said.

present/past tense (someone says something). For 言いました, it would be “someone said something.”

Kanji: 裕子さんはオレンジが好きだと言います。 Kana: ゆうこさんはオレンジがすきだといいます。 Romaji: Yuuko-san wa orenji ga suki da to iimasu. English: Yuuko says she likes oranges.

Yeah, she likes oranges, but the main point is that Yuuko actually said something.

Keep reading

600 notes

·

View notes

Text

あいづち

Paying attention in Japanese

When talking with Japanese people, in English or Japanese, you might notice that they frequently nod or interject something like はい or yes frequently while you are talking. This participatory style of communication characterizes spoken Japanese. With あいづち (aizuchi) or short interjections, the listener is letting you know that they are following you.

If the listener doesn’t show any reaction during a conversation, a Japanese person might feel uneasy and stop and ask if you understand. In some cases they may repeat what they said if they assume you don’t follow the conversation. Over the telephone this might happen if the listener doesn’t respond enough, with the speaker asking もしもし? to see if the listener is still there.

あいづち is an important part of Japanese conversation, and even if it seems strange at first, with enough practice it will become second nature.

Examples of あいづち

はい (does not necessarily mean “I agree” when used as あいづち; formal)

ええ (less formal than はい)

うん (more casual than はい and ええ; sounds closer to a short, hard “mm” sound in English)

ああ (”ah, I see”; less formal)

へえ (”no way”; casual)

そうですか (”is that so?”; formal)

そうですね (”I see”; less formal)

そうっか (”I see”; casual)

そう (”I see”; casual)

そうなんですか (”oh really?”; expresses with extra emphasis)

ほんとうですか (”is that true?”; formal)

ほんとうに (”oh really?”; less formal)

マジ (”really?”; casual)

なるほど (”I see”, “that’s right”; formal)

You can always start with a nod (in person of course) to show the speaker that you’re listening, or interject a friendly はい when the speaker pauses (Japanese people will do this because they are used to receiving あいづち). Then start throwing in a new one each time you have a conversation and you’ll be on your way to becoming an あいづち natural!

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Difference Between ~と言う and ~と言っている

I’ve always read them but never knew understood how to use them. Same with と思います and と思っています, which I will also cover in this post.

~と言う (to iu) is the form you use to directly or indirectly quote what someone has said. と is a quotation marker that can also be used with other verbs like 聞く (to hear)、伝える (to convey)、思う (to think), etc. 言う means to say.

~と言う

places emphasis on the fact the person said something rather than the content of what she said.

present/past tense (someone says something). For 言いました, it would be “someone said something.”

Kanji: 裕子さんはオレンジが好きだと言います。 Kana: ゆうこさんはオレンジがすきだといいます。 Romaji: Yuuko-san wa orenji ga suki da to iimasu. English: Yuuko says she likes oranges.

Yeah, she likes oranges, but the main point is that Yuuko actually said something.

Keep reading

600 notes

·

View notes

Link

Last time, you learned how to make subjects of Japanese verbs with the particles が and は: 雨が降る (new information) and 雪は降らない (contrast). In this lesson, you will learn how to make objects of Japanese verbs by using the particles: を, に, and と.

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New list of most common ADJECTIVES in #Japanese! (Part 17)👈 P.S. Learn Japanese with the best FREE online resources, just click here: https://www.japanesepod101.com/?src=tumblr_special_infographic_adj17_image_111220

293 notes

·

View notes

Text

Turning Right & Left

You might already know the Japanese words for left and right:

左 ひだり left

右 みぎ right

When talking about instructions (driving, walking, etc.), you can tell someone to turn left or right:

左に曲がってください。 ひだりにまがってください。 Please turn left.

右へ曲がりなさい。 みぎへまがりなさい。 Turn to the right.

But when you are talking about making a left or right turn in Japanese, there is another way to say left turn and right turn:

左折 させつ left turn

右折 うせつ right turn

You might see these words on the road:

左折可 させつか left turn permissible

右折禁止 うせつきんし right turn prohibited

左折 and 右折 are common in navigation programs and when giving directions to the person driving.

次の交差点で左折してください。 つぎ の こうさてん で させつ して ください。 Please make a left turn at the next intersection.

自転車は右折した。 じてんしゃ は うせつ した。 The bicycle made a right turn.

ごきげんよ! (That’s bon voyage!)

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

To all of you who studied, practiced, spoke, or immersed yourself to your target language today: keep up the good work, I’m proud of you!

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

spooky japanese vocab 🎃

🎃 ハロウィーン ― halloween

🎃 南瓜 「かぼちゃ」 ― pumpkin

🎃 骸骨 「がいこつ」 ― skeleton

🎃 蝙蝠 「こうもり」 ― bat

🎃 蜘 「くも」 ― spider

🎃 黒猫 「くろねこ」 ― black cat

🎃 満月 「まんげつ」 ― full moon

🎃 ヴァンパイア ― vampire

🎃 吸血鬼 「きゅうけつき」 ― original japanese word for vampire

🎃 血を吸う 「ちをすう」― to suck blood

🎃 幽霊 「ゆうれい」 ― ghost

🎃 狼男 「おおかみおとき」 ― werewolf

🎃 透明人間 「とうめいにんげん」 ― invisible man

🎃 ミイラ ― mummy

🎃 フランケンシュタインの怪物 「フランケンシュタインのかいぶつ」 ― frankenstein’s monster

🎃 魔女 「まじょ」 ― witch

🎃 魔法使い 「まほうつかい」 ― wizard/sorcerer

🎃 魔法の呪文 「まほうのじゅもん」― a magic spell

🎃 魔法の呪文をかける 「まほうのじゅもんをかける」 ー to cast a magic spell

🎃 化け物 「ばけもの」 ― monster

🎃 鬼 「おに」 ― demon (traditional japanese)

🎃 悪魔 「あくま」 ― devil/demon

🎃 お化け屋敷 「おばけやしき」 ― haunted house

🎃 お化け話 「おばけばなし」 ― ghost stories

🎃 怖い 「こわい」 ― scary

🎃 恐ろしい 「おそろしい」 ― horrible

🎃 気味悪い 「きみわるい」 ― creepy/unpleasant

🎃 グロ ― grotesque

🎃 呪い 「のろい」― a curse

🎃 呪う 「のろう」― to curse s/o or s/t

ハッピーハロウィーン!💀 🎃 👻

3K notes

·

View notes