Text

💻 Terms & Conditions: Who Gets to Feel Safe Online?

Welcome to the internet. By using this platform, you agree to the following totally arbitrary and selectively enforced terms of digital existence.

SECTION 1: SAFETY IS A PRIVILEGE, NOT A RIGHT (unless you're a man with a mic)

We at Kaito Z strive to provide a safe and inclusive environment. Unless you're a feminist, queer, trans, or a woman with an opinion.

In that case, your safety is subject to the algorithm, public opinion, and whether a moderator has had their coffee yet. As Haslop (2023) points out, digital governance often fails to protect users from online hostility because platforms prioritize engagement over ethics. Hate = clicks = money. Sorry, babe.

SECTION 2: FREE SPEECH > YOUR DIGNITY

By continuing to post, you accept that:

Your trauma is up for debate.

Misogyny is “edgy humor.”

And if you call it out? You’re just “sensitive” or “a snowflake.”

Trolls often use dog whistles, irony, and coded language to harass while skirting platform rules. It’s the discursive silencing playbook: say something vile, then claim it was a joke. Classic gaslight, gatekeep, girlboss behavior - but from incels.

SECTION 3: #MisandryIsNotReal (But Let’s Pretend It Is)

We understand your confusion. #Misandry trends now and then, are often used as a sarcastic counter to centuries of institutional misogyny. But let’s be clear:

Misandry is not systemically enforced.

No one’s losing a job, safety, or rights over a meme that says “men are trash.”

Meanwhile, women online receive death threats for saying “I don’t like Andrew Tate.”

See the difference? No? Please review Marwick & Caplan (2018) on how “ironic” misogyny creates networked harassment campaigns that make it dangerous just to exist with a profile picture.

SECTION 4: Algorithmic Bias Clause

You acknowledge that Kaito K will:

Promote inflammatory male creators like Andrew Tate

Suppress feminist creators for “violating community guidelines” (translation: being visible)

Use AI moderation tools that somehow flag “trans rights” but miss slurs in all cap.

Fair and balanced? Not so much. Platform governance is less about protecting people and more about protecting profit.

FINAL CLAUSE: Proceed at Your Own Risk

By existing online, you agree to:

Self-moderate your tone to avoid harassment

Screenshot hate before it gets deleted “for context”

Pray the algorithm doesn’t shadowban you for saying “patriarchy”

If this sounds exhausting, it’s because it is. But knowing the rules (and calling them out) is the first step to rewriting them.

Have you ever had a post flagged while someone else got away with hate speech in the comments? Tag your fav “platform double standard” moment below - or just drop a 🔥 if you’re tired of being called a snowflake for having boundaries.

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Broadcasting the Self”: How Twitch Turned Gamers into Performers

Remember when gaming meant sitting alone in your room, yelling at your screen with a bag of chips and no witnesses? Yeah… Twitch said no thanks and handed gamers a stage, a mic, and an audience of thousands.

Welcome to networked broadcasting, where you're not just playing the game, you're playing yourself.

Gaming Is Performance Now

Gone are the days of faceless usernames. On Twitch, you are the content. You're the host, the character, the entertainment. According to T.L. Taylor (2018), Twitch transformed gaming into live, public performance - a mashup of reality TV, improv comedy, and esports. Whether you’re slaying in Valorant or just vibing in “Just Chatting,” your audience expects a show.

And yes, they will spam Ls in the chat if you’re boring.

Audience = Co-stars

Here’s the twist: your audience isn’t just watching. They’re shaping the show in real time. Every emote, comment, donation, and “F in the chat” changes the energy of the stream.

This is what Taylor calls audience co-production. Viewers help create the vibe - kind of like being in a sitcom where the laugh track is live and might roast you.

Platform Economies and the Hustle

Let’s talk money. Twitch isn’t just for fun - it’s work. Streamers juggle: entertaining, moderating chaos, keeping up energy, and building a community. This is called affective labor where streamers perform emotional and social work to maintain their audience and income. Subscriptions, ads, donations, and sponsorships are the goal... but the pressure is very real.

Microcelebrity 101

According to Marwick & Senft, streamers are microcelebrities. They perform authenticity while curating a brand. It’s not just about being good at games, it’s about being watchable. Funny. Relatable. “Someone you’d want to hang out with on Discord.”

Think of Pokimane - just chatting, sipping tea, reacting to memes... and pulling in thousands of viewers. That’s charisma meets platform strategy.

So tell me: who’s your fave streamer and why? Is it the gameplay, the personality, or just the chaos of Twitch chat? Drop your answers (and your Twitch recs) below 👇

References

Keogh, B. (2021). Scenes, styles and subcultures: The Melbourne indie game scene. In Hjorth, L., Richardson, I., & Apperley, T. (Eds.), Exploring play: A new approach to games (pp. 43–60). Routledge.

Taylor, T. L. (2018). Broadcasting ourselves: Twitch and the rise of game live streaming. Princeton University Press.

Hjorth, L., Richardson, I., & Apperley, T. (2021). Exploring play: A new approach to games. Routledge.

Senft, T. M. (2008). Camgirls: Celebrity and community in the age of social networks. Peter Lang.

Marwick, A. (2013). Status update: Celebrity, publicity, and branding in the social media age. Yale University Press.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Instagram Face: Why Everyone Is Starting to Look the Same?

Let’s play a game. Open Instagram. Scroll five selfies. I bet at least three of them look eerily similar: High cheekbones. Snatched jawline. Pouty lips. Smooth glassy skin. Catlike almond eyes. Perfectly arched brows.

Congrats! you’ve just spotted the “Instagram Face.” It’s beautiful. It’s flawless. It’s also... everywhere ;( But how did we get here? Why are different people, across cultures and continents, chasing the same face? Let’s filter this out 🧠

Filtered Reality, Literally

As Rettberg (2014) explains, filters don’t just tweak your lighting: they reshape your reality. Instagram and Snapchat filters nudge users toward aesthetic norms that the algorithm (and culture) favors: thinner noses, bigger eyes, and smoother skin. Over time, users internalize these enhancements as the new baseline.

You’re not just beautifying. You’re editing yourself into the algorithm’s idea of hot. And when millions of people do the same thing? Boom: beauty homogenization.

From FaceTune to Facelift

Enter Coy-Dibley’s (2016) idea of digitized dysmorphia - where people become obsessed with their filtered face to the point they want to look like it IRL. Think: fillers, buccal fat removal, and the rise of “Snapchat dysmorphia.”

TikTok’s “Bold Glamour” filter sparked a wave of creators saying, “Why don’t I look like this in real life?” You don’t... because no one does.

youtube

If Everyone’s Hot, Then Who’s Boring?

The "Instagram Face" creates an illusion of diversity while reinforcing a singular, Westernized beauty ideal. Coy-Dibley (2016) and Rettberg (2017) both point out how platforms offer a “menu” of desirable traits, but the defaults tend to align with whiteness, thinness, and femininity. It’s not just aesthetic - it’s political. Filters erase features, flatten cultural identity, and promote beauty colonialism in digital form.

Software Literacy: Know Your Filter

If we don’t understand how filters shape our self-image, we can’t resist them. This is where software literacy and digital citizenship come in. Choi & Cristol (2021) argue that being a good digital citizen means being critical of the tools we use - especially the ones that quietly train us to hate our unfiltered selves.

Final Thought

Instagram Face didn’t just “happen.” It was built, coded, tested, and normalized. And while filters can be fun and creative, they’re also ideological machines, shaping how we see beauty - and ourselves.

So next time you reach for that beauty filter, ask yourself: Are you enhancing… or erasing?

Seen any wild “Instagram Face” trends lately? Or have a favorite creator who keeps it beautifully unfiltered? Drop it in the tags. Let’s celebrate faces that aren’t factory settings.

References

Choi, M., & Cristol, D. (2021). Digital citizenship with intersectionality lens: Towards participatory democracy driven digital citizenship education. Theory Into Practice, 60(4), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2021.1987094

Coy-Dibley, I. (2016). ‘Digitized dysmorphia of the female body: The re/disfigurement of the image’. Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, 30(2), 126–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2016.1141868

Rettberg, J. W. (2014). Seeing Ourselves Through Technology: How We Use Selfies, Blogs and Wearable Devices to See and Shape Ourselves. Palgrave Macmillan.

Rettberg, J. W. (2017). Biometric citizens. In A. T. Kenney, M. D. Witmer, & A. J. Tinkcom (Eds.), Theories of the Mobile Internet (pp. 123–138). Routledge.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Are We So Obsessed with Bodies and Beauty?

Our obsession with bodies isn’t just skin deep - it’s shaped by evolution, culture, capitalism, and code. From ancient survival instincts to today’s Instagram filters, our understanding of beauty is constantly constructed, surveilled, and sold back to us.

🧬 Evolutionary Psychology

From a biological standpoint, humans are drawn to traits associated with fertility and health - symmetry, clear skin, and certain body ratios. This is rooted in evolutionary psychology, where beauty signals reproductive fitness (Etcoff, 1999).

But in the age of TikTok and face filters, this instinct gets hijacked. Platforms amplify hyper-idealized versions of beauty, shaping what we think is attractive through repetition and algorithmic reward. As Carah and Dobson (2016) describe, this results in algorithmic hotness, where attractiveness isn’t just about looks - it’s about platform-optimized performance.

Feminist Body Theory: The Body as Text

Feminist scholars like Sandra Bartky (1990) and Susan Bordo (1993) argue that the body is a social construct, shaped by discipline and power. What’s considered “beautiful” or “normal” is written by dominant cultures - and upheld by industries, media, and now... platforms.

Postfeminist culture rebrands sexualized self-presentation as empowerment, but in practice, it often demands unpaid aesthetic labor (Drenten et al., 2020). So, your body isn’t just you - it’s content, currency, and capital.

#ThatGirl TikTok. Aesthetic wellness? Or a soft filter over class, privilege, and disordered eating?

youtube

Platformization and Prosumption

As theorized by Theocharis et al. (2022), platform affordances (like likes, filters, and discoverability) reshape how we perform online. Beauty becomes a data-driven project - curated for maximum engagement. Prosumption (Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010) explains how we’re both producers and consumers - creating content that simultaneously expresses identity and feeds the platform's profit model. Your mirror selfie? It’s not just self-expression; it’s monetized microcelebrity.

Sexualized Labour & Digital Capital

Drenten et al. (2020) introduce the idea of sexualized labour, where influencers, especially women, strategically blend emotional work, aesthetic work, and sexual appeal to maintain visibility and income.

They also define connective labour - the hustle of staying relevant through hashtags, tags, and engagement. It’s not just looking good - it’s doing good (for the algorithm), 24/7.

🧠 Beauty is also a talent!

But hey, let’s not throw our skincare routines out with the critical theory. There’s also an upside to our collective obsession with beauty. When channeled positively, the pursuit of aesthetics can motivate people to live healthier, care more about themselves, and embrace self-improvement. As the trend of “beauty from within” grows - think: gut health, mental clarity, clean eating - it shows that the definition of beauty is slowly expanding beyond just the surface.

This aligns with Choi and Cristol’s (2021) notion of digital citizenship, where participating in online beauty conversations can also mean sharing health knowledge, supporting wellness communities, and building body-positive spaces. Even the pressure to “look good” can push people to exercise, sleep better, drink more water, and explore holistic well-being - not just for the algorithm, but for themselves. So yes, beauty culture can be messy, but it can also be a gateway to personal growth, health education, and even joy.

💅 Is your beauty routine just for the ‘gram, or does it feed your soul too? Drop your fave “feel-good” habit or wellness creator in the comments - because beauty is better when it’s holistic.

References

Bartky, S. L. (1990). Femininity and domination: Studies in the phenomenology of oppression. Routledge.

Bordo, S. (1993). Unbearable weight: Feminism, Western culture, and the body. University of California Press.

Etcoff, N. (1999). Survival of the prettiest: The science of beauty. Anchor Books.

Carah, N., & Dobson, A. S. (2016). Algorithmic hotness: Young women’s “promotion” and “prosumer labor” on social media. Social Media + Society, 2(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116672885

Theocharis, Y., Barbera, P., Fazekas, Z., & Popa, S. A. (2022). Platform affordances and political participation: How social media reshape political engagement. West European Politics, 46(4), 788–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2087410

Drenten, J., Gurrieri, L., & Tyler, M. (2020). Sexualized labour in digital culture: Instagram influencers, porn chic and the monetization of attention. Marketing Theory, 20(4), 435–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593119826141

Ritzer, G., & Jurgenson, N. (2010). Production, consumption, prosumption: The nature of capitalism in the age of the digital “prosumer”. Journal of Consumer Culture, 10(1), 13–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540509354673

Choi, M., & Cristol, D. (2021). Digital citizenship with intersectionality lens: Towards participatory democracy driven digital citizenship education. Theory Into Practice, 60(4), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2021.1987094

1 note

·

View note

Text

Slow Fashion, Fast Feelings: What Your Wardrobe Says About Your Attachment Style?

So here’s a weird thought: What if your love life and your wardrobe had more in common than you think? Welcome to Week 6, where we’re stitching together sustainability and emotional chaos, aka: Slow Fashion Movement x Attachment Styles ;)

Slow Fashion Movement 101

Slow fashion is a movement that pushes back against the chaotic mess of fast fashion. It advocates for:

Fair treatment of garment workers (Henninger et al., 2017)

Environmental sustainability (Chi et al., 2021)

Respect for cultural craftsmanship and long-term values (Domingos, 2022)

It can be said that, while fast fashion encourages impulse, overconsumption, and burnout (relatable?), slow fashion leans into intention, care, and commitment. You know, like a healthy relationship ;) just like the secure attachment style below...

Secure Attachment Style: “I care, and I’m not here for the clout.”

According to John Bowlby (1969) and later finalized by Mary Ainsworth (1978), attachment theory explains how individuals form emotional bonds and navigate relationships based on their early experiences, shaping patterns of trust, intimacy, and dependency throughout life.

People with a secure attachment style know what they want and support it wholeheartedly - whether it’s a partner or a movement on social media.

Example: David and Victoria Beckham

Since meeting in 1997, they’ve supported each other’s careers - Victoria’s slow fashion label and David’s steady sports legacy (with coordinated outfits along the way). This reflects consumer behavior driven by long-term values: commitment to sustainability, emotional connection to craftsmanship, and high perceived consumer effectiveness (PCE) (Chi et al., 2021).

People with a secure attachment style tend to support the slow fashion movement because they genuinely align with its values. They believe in ethical change, take the time to educate themselves, and share the message out of love, not social pressure.

Anxious Attachment Style: “I Follow Slow Fashion Because It’s Trending”

Some people join the slow fashion movement not out of values, but out of fear of being left out. They repost every infographic, join every trend, and burn out quickly because their motivation is external validation. This echoes anxious attachment styles, where people latch onto causes in hopes of feeling worthy or accepted. It’s not about slowness - it’s about being seen doing the right thing (Chi et al., 2021; Ajzen, 1991).

📺 Example: YOU (Netflix)

Joe’s obsessive behavior mirrors anxious attachment. He stalks, manipulates, and controls Beck - not out of love, but out of fear of abandonment. He needs constant closeness and validation, even if it means… trapping people in a bookstore cage.

youtube

Just like anxious consumers might cling to movements like slow fashion for identity, Joe clings to love like it's a limited edition drop!

Avoidant Attachment Style: “I’d Rather Be Alone… And Sponsored”

Avoidantly attached people might intellectually agree with slow fashion but keep their distance emotionally. They don't engage in dialogue, avoid activism that feels “too much,” and support from afar.

This passive participation reflects a discomfort with vulnerability and accountability. In digital activism terms, it's the equivalent of liking every post... but never sharing your thoughts or joining conversations (Theocharis et al., 2022).

In The End: It’s All About Education...

Whether we’re talking about fashion or love, it all comes down to how people are educated and supported. NGOs, brands, and even families play a role in teaching conscious care - both in what we buy and how we love.

Because in the end, a well-made linen shirt (or a securely attached partner) isn’t just for show. It’s for keeps.

So, let’s be honest: Are you here for the movement, the mood board, or both?

Let me know what kind of slow fashion lover you are - and no, “emotionally unavailable but eco-conscious” isn’t off the table. 😉

References Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books.

Brewer, J. (2019). Slow fashion in a fast fashion world: Promoting sustainability and responsibility. [PDF]. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.15729.76641

Chi, T., Wu, Y., Wang, Y., & Zhang, M. (2021). Understanding consumers’ intention to purchase sustainable fashion products: The moderating role of future orientation. Sustainability, 13(3), 1681. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031681

Domingos, R., Rausch, A., & Christophel, M. (2022). A systematic literature review on slow fashion: Exploring sustainable consumption in the fashion industry. Sustainability, 14(21), 13937. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113937

Henninger, C. E. (2016). What is sustainable fashion? Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 20(4), 400–416. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-07-2015-0052

1 note

·

View note

Text

#POV: Is Digital Public Space Becoming a Refuge from Face-to-Face Interaction?

Was the online public space created to avoid real-life communication? (¬‿¬)?

The concept of the "public space," introduced by Habermas in the 1990s, refers to a space where citizens discuss public issues and shape opinions. Initially considered a physical gathering place, it now includes media networks for information exchange. An ideal public space is participatory and safeguards against power abuse (Habermas, Kruse et al., 1991, 2018). Accordingly, social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram have been argued to be new media spaces where public entities interact with audiences (Erlis Cela, 2015).

"POV" (Point of View) content is readily available through social media platforms such as TikTok or Threads. These posts allow users to freely express their opinions without the immediate pressure of criticism (Elvira et al., 2023).

But when a POV video garners hundreds of thousands of interactions overnight, we have to ask: Are digital communities fostering dialogue, or are they becoming echo chambers where we talk at, rather than with, each other?

Sharing but Not Engaging

POV content thrives on TikTok and similar platforms because it lets users present their thoughts in a controlled environment, without direct confrontation. A simple video with the right framing, a catchy caption, and a trending sound can make a strong statement. But here's the catch: they're talking, yet not truly engaging in conversations.

This brings us to a bigger question: Are digital communities real "public spheres" or just curated spaces that allow us to avoid confrontation? According to Kruse (2018), a true public sphere facilitates open, reasoned discourse that can drive political and social change. It requires unrestricted access, equal participation, and freedom from external control (Jonathon Hutchinson, 2021). But do social media platforms meet these ideals?

Threads: Public, Yet Private?

Meta introduced Threads as an ad-free, open platform for sharing thoughts (Bone et al., 2018). Yet, when evaluated against the core principles of a public sphere - open dialogue, rational discourse, and critical engagement (Kruse, 2018), digital communities often fall short. Threads might feel like a safe space, but is it truly fostering meaningful discussions, or is it just reinforcing users' pre-existing viewpoints?

Thread - Connecting or Avoiding? Some argue that younger generations are steering away from face-to-face discussions, choosing digital spaces instead for self-expression (Fischer and Otfried Jarren, 2023).

🔹 The Upsides:

Online platforms provide a space where individuals can share their thoughts without the immediate pressure of backlash. For example, on platforms like TikTok and Threads, users can post their own opinions and engage in discussions at their own pace, without fear of real-time criticism.

Additionally, digital spaces offer a safe environment for marginalized voices to be heard, allowing individuals from underrepresented communities to participate in conversations that might be inaccessible in traditional public forums. Moreover, for those with social anxiety or difficulties with verbal communication, online platforms provide an accessible way to express themselves and engage with others.

🔻 The Downsides:

One major concern is the creation of "echo chambers," where people are exposed only to opinions that align with their own, reinforcing existing beliefs rather than challenging them. For instance, algorithms on social media often prioritize content that users already agree with, limiting exposure to diverse perspectives. Additionally, reliance on digital communication may lead to a decline in direct, critical thinking and debate skills, as face-to-face interactions require immediate responses and engagement.

Furthermore, not everyone has equal access to digital spaces - factors such as digital literacy, economic disparities, and racial biases affect who gets to participate in these discussions. For example, individuals from lower-income backgrounds may lack the necessary devices or internet access, creating a digital divide that limits their ability to engage in public discourse. While digital public spaces offer new opportunities for communication, they also present challenges that need to be addressed to ensure inclusive and meaningful participation.

So, personal point of view or 2-way communication?

Platforms like Twitter, Threads, and TikTok make it easier than ever to share opinions - but does that mean we’re actually engaging? Are digital communities bridging gaps, or simply giving us a way to avoid tough conversations? What do you think?

Reference

Bone, M., Blackburn, M., Kruse, B., Dzielski, J., Hagedorn, T. and Grosse, I., (2018). Toward an interoperability and integration framework to enable digital thread. Systems, 6(4), p.46.

Jonathon Hutchinson (2021) Micro-platformization for digital activism on social media, Information, Communication & Society, 24:1, 35-51, DOI: 10.1080/1369118X.2019.1629612

Elvira, B.L., Firdaus, R. and Adi Setijowati (2023). The Influence of POV Trend as a Branding Image Content Creator on TikTok. Zenodo (CERN European Organization for Nuclear Research). [online] doi:https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8340763.

Buffer: All-you-need social media toolkit for small businesses. (2024). We Analyzed 10.2 Million Threads and X Posts—What We Found. [online] Available at: https://buffer.com/resources/threads-vs-twitter/ [Accessed 16 Feb. 2025].

Levin, S. (2022). US Capitol attack: is the government’s expanded online surveillance effective? [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/jan/07/us-capitol-attack-government-online-surveillance [Accessed 16 Feb. 2025].

Erlis Çela (2015). Social Media as a New Form of Public Sphere. European Journal of Social Sciences Education and Research, [online] 4(1), pp.195–195. doi:https://doi.org/10.26417/ejser.v4i1.p195-200.

Habermas, J. (1991). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Translated by Thomas Burger. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kruse, L. M, Norris, D. R & Flinchum, J. R. (2018). Social media as a public sphere? Politics on social media, The Sociological Quarterly, 59:1, 62-84.

Fischer, R. and Otfried Jarren (2023). The platformization of the public sphere and its challenge to democracy. Philosophy & Social Criticism, [online] 50(1), pp.200–215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/01914537231203535.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Which Personalities Are Crafted for Reality TV Stars?

Yes, you heard it right. Most of the personalities in reality shows are actually scripted (´・ᴗ・ ` )

Reality TV: More Than Just “Reality”

Imagine Keeping Up with the Kardashians without drama or Single’s Inferno without love triangles - would it still be entertaining? Reality TV isn’t just about unfiltered interactions; it’s about storytelling. Scripted personalities ensure engagement, virality, and emotional investment.

youtube

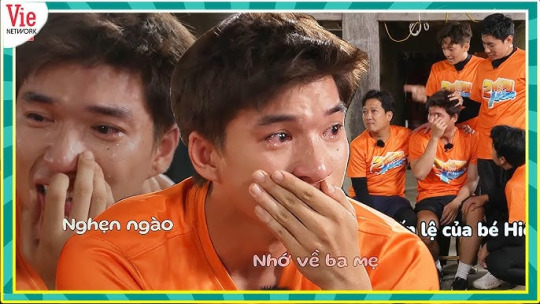

Take Hiếu Thứ Hai - a Vietnamese idol, for example.

His portrayal of Hai Ngày Một Đêm as a humble yet strategic team leader solidified his image as a relatable and charismatic figure, enhancing his appeal both on and off-screen.

Scripted Archetypes: The Good, The Bad & The Viral

While marketed as unscripted, reality TV is often highly curated, with producers shaping narratives through selective editing and casting. According to Deller (2019), reality television operates on "the illusion of spontaneity," but in practice, it follows structured formulas designed to maximize drama and viewer engagement.

Contestants are not just participants; they are characters molded to fit archetypal roles that enhance the show’s storytelling. As Stewart & Mark (2020) argue, reality TV blends authenticity with performance, creating a hybrid space between real life and entertainment. Furthermore, social media amplifies these narratives, transforming contestants into public figures whose personas extend beyond the screen (Lovelock &Michael, 2019). While some embrace their roles, others find themselves misrepresented, reinforcing the power dynamics between production teams and audience perceptions.

Ultimately, reality TV is not a mirror of society but rather a constructed entertainment space that thrives on controlled chaos to maintain audience interest and commercial viability (Deller, 2019).

So, has anyone ever wondered what common character archetypes are often crafted for reality TV cast members? Here are some of the most iconic ones, along with insights into how they contribute to a show’s success.

🏆 The Hero: Everyone admires.

✔️ Hardworking, talented, and emotionally intelligent.

✔️ Often makes it to the finale (or at least becomes a fan favorite).

✔️ Loved by judges and audiences alike, often seen as a role model.

In this case, Hiếu Thứ Hai – known as “the nation’s husband,” is the figure adored by millions of female fans in Vietnam;’)

🔥 The Villain: Everyone loves to hate (or secretly just loves).

✔️ Highly competitive, aggressive, or manipulative.

✔️ Involved in the most conflicts, often edited to appear heartless.

In Love Paradise Vietnam 2024, sparked intense controversy over contestant Mạnh Kiên.

Mạnh Kiên was framed as a controlling, traditionalist figure, portrayed as the ultimate antagonist to female contestants. A key moment? His interactions with Yuna, where he repeatedly insisted she address him formally with "Yes, sir" during their conversations. This immediately triggered outrage on social media, leading to calls for his elimination. Eventually, he was voted out, but in an unexpected twist, audiences demanded his return, arguing that the show wasn’t as entertaining without him.

🤣 The Comic Relief: may not be the best at competing but is definitely the most entertaining.

✔️ Known for their hilarious reactions, witty remarks, and meme-worthy moments.

✔️ Rarely wins, but often becomes a fan favorite.

Lê Dương Bảo Lâm (Hai Ngày Một Đêm) - Constantly failing tasks but keeping the audience entertained.

💔 The Underdog: starts off underestimated but wins hearts over time.

✔️ Faces obstacles but perseveres.

✔️ Often has an emotional backstory that makes audiences root for them.

Many contestants in Rap Viet follow this arc, starting as overlooked contenders and evolving into top competitors. Many former contestants have revealed that villain edits are often crafted through selective editing rather than reflecting reality. While heroes and underdogs are beloved, it’s often the villain who drives the conversation. Being “hated” doesn’t always mean failure - some of the most controversial contestants become the most famous after the show.

So, How “Real” Is Reality TV?

However, there is a fine line between engaging in reality TV and harmful misrepresentation. Some shows go too far, using editing tricks to amplify negative traits for the sake of drama. At the end of the day, reality TV is a blend of reality and entertainment, where characters are shaped as much by producers as by the contestants themselves (Misha Kavka, 2018)

📢 Who’s your favorite reality TV personality? Do you think they were playing a scripted role? Drop your thoughts in the comments!

Reference

Deller, R.A. (2019). Reality Television: The Television Phenomenon That Changed the World. [online] Emerald Publishing Limited. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/9781839090219.

Stewart, Mark (2020) ‘Live Tweeting, Reality TV and the Nation’ Download ‘Live Tweeting, Reality TV and the Nation’23(3) International journal of cultural studies 352.

Lovelock, Michael (2019) 'Introduction' in 'Reality TV and Queer Identities: Sexuality, Authenticity, Celebrity' Download 'Reality TV and Queer Identities: Sexuality, Authenticity, Celebrity'Springer International Publishing AG.

L'Hoiry, X. (2019) 'Love Island, social media, and sousveillance : new pathways of challenging realism in reality TV'. Frontiers in Sociology, 4. 59: https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00059Links to an external site.

Misha Kavka (2018) ‘Reality TV: Its contents and discontents’, Download ‘Reality TV: Its contents and discontents’, Critical Quarterly 60(4): 5-18; DOI: 10.1111/criq.12442

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Digital Citizens: The New Political Powerhouses?

Welcome to the Internet, where your Tweets might just change the world (✧ω✧)

Once upon a time, politics was something that happened on TV while we ignored it in favor of cat videos. Fast forward to today, and hashtags are toppling governments, livestreams are causing constitutional crises, and “likes” hold more power than some politicians’ speeches. So, welcome to the era of digital citizenship - where anyone with Wi-Fi and a strong opinion can contribute to political discourse.

What Even Is Digital Citizenship?

Simply put, digital citizenship is your ability to engage responsibly, critically, and effectively in online spaces (Choi et al., 2021). But let’s be real - it’s also about how many times you’ve accidentally ended up in a Twitter war with a stranger over pineapple on pizza.

For some, digital citizenship means being an informed and active participant in democracy online (Theocharis, 2022). For others, it’s just knowing when to close the comment section before your blood pressure spikes.

But when do digital voices come together? That’s when things get interesting.

Hashtag Publics: When the Internet Decides to Change the World

Social media has evolved into a battleground for political engagement, activism, and rapid mobilization. Movements like Black Lives Matter used #BlackLivesMatter to spread awareness, mobilize protests, and push for policy changes, forcing mainstream media and politicians to respond. Similarly, during the 2016 U.S. election, platforms shaped public discourse, influenced voter turnout, and became essential for fundraising (Enli, 2017).

Hashtags and viral content now drive activism, with digital spaces serving as arenas for real-world action. This reflects platformization, where social media is no longer just for discussion - it’s a tool for organizing, resisting, and directly shaping political outcomes (Choi et al., 2021; Carruthers, 2018)

From Tweets to the Streets: The Power of Digital Protest

One of the most striking examples of digital activism leading to real-world consequences happened in South Korea in 2024, when a politician attempted to enforce martial law under the guise of national security.

youtube

As government officials debated the issue behind closed doors, an activist took matters into his own ultimately - climbing a wall and live streaming himself breaking into the secretive meeting (Guinto, 2025).

youtube

Within minutes, the footage went viral, sparking outrage across social media. Hashtags calling for government accountability flooded platforms, and within hours, South Korean citizens organized protests across major cities.

youtube

youtube

The rapid mobilization of digital citizens transformed into mass demonstrations, forcing the government to backtrack on the martial law decision and ultimately leading to the arrest of the president involved in the scandal (Lee, 2025). This event is a prime example of platformizatanym - where social media isn’t just a tool for discourse, but an arena for action, turning digital dissent into tangible political consequences (Choi et al., 2021). Whether it’s hashtags shaping narratives, viral videos exposing corruption, or live streams acting as real-time calls to action, the internet is now a force that governments can no longer ignore.

So, What’s Next?

As elections, protests, and political drama continue to unfold, digital citizens aren’t just commenting - they’re participating, influencing, and rewriting the rules. The internet isn’t just a space for scrolling anymore. It’s where real change starts - one viral post at a time.

📢 Do you think digital citizenship should be considered as valid as traditional political participation? Drop your thoughts in the comments! Or better yet - start a revolution ;) Reference

Carruthers, C. A. (2018). Unapologetic: A Black, queer, and feminist mandate for radical movements. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press.

Choi, M. and Cristol, D. (2021). ‘Digital citizenship with intersectionality lens: Towards participatory democracy driven digital citizenship education’, Theory Into Practice, 60(4), pp. 361–370. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2021.1987094.

Enli, G. (2017). ‘Twitter as arena for the authentic outsider: exploring the social media campaigns of Trump and Clinton in the 2016 US presidential election’, European Journal of Communication, 32(1), pp. 50-61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323116682802.

Theocharis, Y. et al. (2022). ‘Platform affordances and political participation: how social media reshape political engagement’, West European Politics, 46(4), pp. 788–811. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2022.2087410.

3 notes

·

View notes