Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Model reconstruction of the Templo Mayor, Wolfgang Sauber, (National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City).

Templo Mayor

The Great Temple located in Tenochtitlan, sat in the center of the city. With two grand stairways leading to the top of the temple, where two sanctuaries would be found.¹ Stairs so long if not accustomed to would result in tumors and abscesses, as described by Díaz del Castillo.² One of the sanctuaries was dedicated to Huitzilopochtli, the god of the sun and war. The other served Tlaloc, the god of rain and fertility.³ Inside their sanctuaries were two giant tall figurines. The one on on the right was of Huitzilopochtli, having a "broad monstrous face", and his body covered with precious stones. Holding a bow in one hand and a bow in the other.⁴ The other statue of Tlaloc was of a half man half lizard, whose body was said to contain all the seeds in the world. In front of them was a "techcatl" a round stone used for making sacrifices.⁵ Rituals were a daily occurrence in this temple, resident priests maintained the worship of the two gods by praying, burning incense, offering blood, and rarely sacrificing a human.⁶ Offers were made for Tlaloc to prevent drought, that he would send his rain for their crops. His offerings consisted of shells, fish, and sculptures of aquatic creatures. In contrast to Huitzilopochtli whose were skulls and sculpted knives. A contrast between the god of Fertility and the god of war.⁷ Huitzilopochtli's victims sacrificed on his side would have their hearts taken out, and thrown down his stairs. Landing on a statue of his sister Coyolxauhqui, which signified their weakness being thrown on a "defeated woman" This comes from the story of Huitzilopochtli killing his sister as revenge for attempting to murder him before his birth.⁸ Human Sacrifices kept Huitzilopochtli "satiated and happy".⁹ The Templo Mayor was extremely sacred to the Aztecs with its placement in the center of the whole city linked to the creation of Tenochtitlan. When Huitzilopochtli guided the four priests to find a nopal cactus tree which would signify they had found their home. That tree was said to have become Templo Mayor.¹⁰

------------------------------------------------------

Bibliography

Díaz del Castillo, Bernal. The Conquest of New Spain, Vol. 2. E-book. Nendeln: Kraus Reprint, 1967, URL

Diel, Lori Boornazian. Aztec Codices: What They Tell Us about Daily Life. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2020. URL

Moctezuma, Eduardo Matos. Archaeology & Symbolism in Aztec Mexico: The Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan. Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 1985. URL

-----------------------------------------------------

Eduardo Matos, Moctezuma, Archaeology & Symbolism in Aztec Mexico: The Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan (Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 1985,) p799, URL

Bernal, Díaz del Castillo, The Conquest of New Spain, Vol. 2. E-book, (Nendeln: Kraus Reprint, 1967,) p79 URL

Moctezuma, Eduardo Matos, Archaeology & Symbolism in Aztec Mexico: The Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan, p799

Díaz del Castillo, Bernal, The Conquest of New Spain, Vol. 2. E-book, p76

Moctezuma, Eduardo Matos, Archaeology & Symbolism in Aztec Mexico: The Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan, p804

Lori Boornazian, Diel, Aztec Codices: What They Tell Us about Daily Life, (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2020,) p142 URL

Diel, Lori Boornazian, Aztec Codices: What They Tell Us about Daily Life, p151

Diel, Lori Boornazian, Aztec Codices: What They Tell Us about Daily Life, p152

Diel, Lori Boornazian, Aztec Codices: What They Tell Us about Daily Life, p168

Diel, Lori Boornazian, Aztec Codices: What They Tell Us about Daily Life, p142

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ballcourt in the Codex Borgia

Ullamaliztli (religious ceremony)

Ullamaliztli is a mesoamerican ballgame played by the Aztecs. Where a ball made of rubber, where each player would "kick" the ball with their hips.¹ It would be played in a court on an oblong-shaped field, with wider ends giving it the look of a capitalized I. A thick wall would surround the field, and in the middle of the wall, there would be a high ring which was the goal.² The ball weighed 2.5 kilograms and it could not touch the ground. It was only permitted to be kicked with the hips, head, elbows, and knees. The players wore protective shields, but they would still come out with bruises and bleeding. The Aztecs enjoyed gambling and used Ullamaliztli as an outlet too. With the loser needing to give up a daughter or wife to the winner. Even becoming slaves to the winning man.³ The court symbolized the Aztec underworld, with Ullamaliztli being a reenactment of day and night opposite forces, as the sun passes through the underworld to rise back up. This significance comes from the nature of the gods they worshipped dealing with elemental and cosmic manifestations. Such as gods of the sun, moon, rain, earth, and stars, based on a calendar cycle which determines the people's prosperity.⁴ An interpretation of this ritual is that the ball is the goddess of the moon's head. Representing her decapitation by Huitzilopochtli the sun god. Showing the light defeating the dark. It is said they played in specific equinoxes or months to influence the movement of the sun as it passes through the underworld⁵. The Aztecs used a ritual where they would choose someone to impersonate a god and then sacrifice them. In this ceremony, a player would be chosen to represent the moon goddess, and at the end of the game would be sacrificed to complete the ritual.⁶ The religious aspect of this game is to maintain a cosmic balance as many Aztec rituals are performed in order to prevent cataclysmic events.

-----------------------------------------------------

Bibloagraphy

Cohodas, Marvin. The Symbolism and Ritual Function of the Middle Classic Ball Game in Mesoamerica. American Indian Quarterly, vol. 2, no. 2, 1975, URL

Maries-Les, Gabriela. AZTECS - CIVILIZATION, CULTURE AND SPORTIVE ACTIVITIES: ACCES LA SUCCES. Calitatea 13, no. 2 05, 2012 URL

Leyenaar, Ted J. J. Ulama the Survival of the Mesoamerican Ballgame Ullamaliztli. Kiva 58, no. 2, 1992. URL

------------------------------------------------------

Ted J.J., Leyenaar, Ulama the Survival of the Mesoamerican Ballgame Ullamaliztli, (Kiva 58, no. 2, 1992,) p117, URL

Leyenaar, Ted J.J., Ulama the Survival of the Mesoamerican Ballgame UllamaliztlI, p119

Gabriela, Maires-Les, AZTECS - CIVILIZATION, CULTURE AND SPORTIVE ACTIVITIES: ACCES LA SUCCES. (Calitatea 13, no. 2 05, 2012,) URL

Marvin, Cohodas, The Symbolism and Ritual Function of the Middle Classic Ball Game in Mesoamerica, (American Indian Quarterly, vol. 2, no. 2, 1975,) p102, URL

Cohodas, Marvin, The Symbolism and Ritual Function of the Middle Classic Ball Game in Mesoamerica, p109

Cohodas, Marvin, The Symbolism and Ritual Function of the Middle Classic Ball Game in Mesoamerica, p109-110

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dough statue of Huitzilopochtli as the Tzitzimitl Omitecuhtli, wearing the skulls and crossbones cape and receiving offerings of dough bones during Toxcatl, Florentine Codex

Huitzilopochtli Statue

Huitzilopochtli the most celebrated god of the Aztecs, celebrated during the month of Toxcatl.¹ A god of war and the sun, also representing the finding of Tenochtitlán. The Aztecs believed that four priests carried Huitzilopochtli in the form of a hummingbird. With the god directing them to find "an eagle perched on a cactus that bore a large red fruit" symbolizing that they had found their new home away from Aztlán. They had found it with Tenochtitlán creation.² During the festivities for Huitzilopochtli the Aztecs would make a statue of him in the temple of Huitznahuac, using "Fish-amaranth dough" to make it seem as if he had flesh. He was then decorated with human limbs and was covered with a cape made of feathers.³ Huitzilopochtli's statue also wore "a cloth jacket or vest decorated with the image of human bones. It wore a distinctive hat made of paper that was wider at the top than at the brim so that it looked like a bowl and was decorated with feathers and a flint knife," his attire representing death. After his image was made he was moved to a sanctuary where rituals would be done in his presence. Such as cutting off the heads of four quails, salted and eaten by the monarch.⁴ Huitzilopochtli was also celebrated in the fifteenth month of Panquetzaliztli, which was significant to the Aztecs because they had to pay tribute to the Triple Alliance (Tenochtitlan, Tetzcoco, and Tlacopan)⁵, which only required in four months.⁶ During Panquetzaliztli statues of Huitzilopochtli were also made, however, this image of him was very different. Being instead of a human-sized deity impersonator (ixiptla) on a wooden frame made from tzoalli.⁷ Tzoalli was a mixture of ground amaranth seeds and dark maguey syrup which made a paste used to make statues of their gods. This paste was made by young women or girls aged twelve to thirteen who were dedicated to Huitzilopochtli. Making the final dough rested on the hands of the priests, who carefully made sure it was pristine with no debris. Then Huitzilopochtli was ready to be created.⁸

---------------------------------------------------

Bibloagrpahy

"Codex Mendoza." In Biographies and Primary Sources, edited by Benson G Sonia, Hermsen Sarah, Baker Deborah J., 209-219. Vol. 3 of Early Civilizations in the Americas Reference Library. Detroit, MI: UXL, 2005. Gale In Context: World History. URL

Boone Elizabeth H. Incarnations of the Aztec Supernatural: The Image of Huitzilopochtli in Mexico and Europe. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 79, 1989. URL

Schwaller, John F. The Fifteenth Month: Aztec History in the Rituals of Panquetzaliztli. University of Oklahoma Press, 2019.

----------------------------------------------------

Elizabeth Boone, Incarnations of the Aztec Supernatural: The Image of Huitzilopochtli in Mexico and Europe, (Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 79, 1989,) p1

Sonia G. Benson, Sarah Hermsen, Deborah J. Baker, Vol. 3 of Early Civilizations in the Americas Reference Library (Detroit, MI: UXL, 2005. Gale In Context: World History,) URL

John F. , Schwaller, The Fifteenth Month: Aztec History in the Rituals of Panquetzaliztli, (University of Oklahoma Press, 2019,) p129

Schwaller John F., The Fifteenth Month: Aztec History in the Rituals of Panquetzaliztli, p130

Schwaller John F., The Fifteenth Month: Aztec History in the Rituals of Panquetzaliztli, p7

Schwaller John F., The Fifteenth Month: Aztec History in the Rituals of Panquetzaliztli, p9

Schwaller John F., The Fifteenth Month: Aztec History in the Rituals of Panquetzaliztli, p130

Schwaller John F., The Fifteenth Month: Aztec History in the Rituals of Panquetzaliztli, p95

0 notes

Text

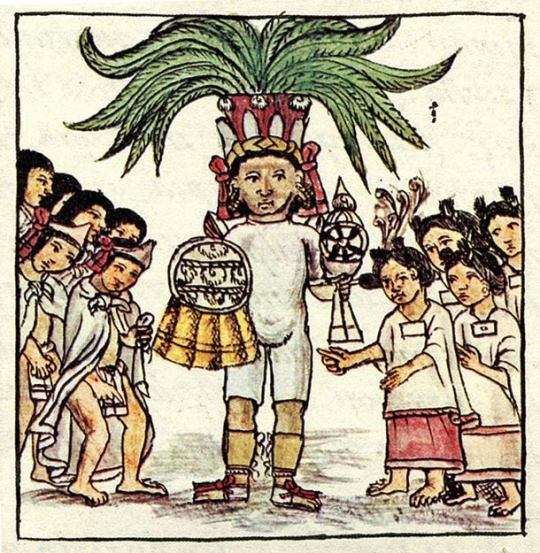

The ‘ixiptla’ of Tezcatlipoca during the Toxcatl festival; Florentine Codex Book II

Toxcatl Festival

The most important festival for the Aztec people was the festival of Toxcatl, which they primarily dedicated to one of their gods Tezcatlipoca.¹ It was held during the 5th month, which they also named Toxcatl"² The purpose of the festival was to ask the gods for rain, as this time was the dry season.³ To appease their gods they would select the most handsome men they had captive, and embellish him in the image of Tezcatlipoca.⁴ He would be trained for a year in "the arts of playing music, singing, and speaking."⁵ He was to be made so beautiful the people would bow to him as if it was Tezcatlipoca himself.⁶ Once his day of sacrifice had arrived he would roam the city freely as he played his flute.⁷ Set free for the people to worship and adore him, some going as far as to kiss the ground he walked on. He would be heard all over with bells strapped to his ankles.⁸ After all the feasts and banquets were held for him, being adorned with the highest attire, and treated as a god. His day of sacrifice was next, on this day he would be stripped of everything, then sent to be away from the city and be killed for the gods. By taking his heart and showcasing it to the sun.⁹ The message sent to the people with his death was "Those who enjoy riches and delights in this life will end up in poverty and sorrow at the end of their lives."¹⁰ A testament to the Aztec people that worldly pleasures would not serve them. This festival seems brutal and cruel, but to the Aztec people, death is a natural part of the life cycle, which decides their afterlife. With an honorable death permitting you to enter paradise. "The Aztecs believed that where you went after death depended upon what you did on earth and how you died. The eastern paradise, the “house of the sun” was the home of the souls of warriors who were killed in combat"¹¹ It is also important to note that since this information comes from the Florentine Codex which was written under Spaniard supervision, the practices and festivals of the Aztecs may have been brutalized and exaggerated. To justify their own agenda of bringing god to these "barbaric" people and their festivals.

-----------------------------------------

Bibliography

Nutini Hugo G. Pre-Hispanic Component of the Syncretic Cult of the Dead in Mesoamerica. Ethnology 27, 1988. URL

Richter N. Kim, Houtrouw Alicia Maria. Book 2: The Ceremonies Florentine Codex. Getty Research Institute, 2023. URL

Dils Lora. Understanding the Ancient Americas: Foundation, Flourishing, and Survival. Yale University: Yale-New Haven Teachers, 1994. URL

----------------------------------------

Hugo G. Nutini, Pre-Hispanic Component of the Syncretic Cult of the Dead in Mesoamerica, (Ethnology 27, 1988,) p9, URL

Kim N. Richter, Alicia Maria Houtrouw, Book 2: The Ceremonies Florence Codex, (Getty Research Institute, 2023.) p30r, URL

Nutini Hugo G., Pre-Hispanic Component of the Syncretic Cult of the Dead in Mesoamerica, p9.

Richter Kim N., Book 2: The Ceremonies Florentine Codex, p30r

Richter Kim N., Book 2: The Ceremonies Florentine Codex, p31v

Richter Kim N., Book 2: The Ceremonies Florentine Codex, p31v

Richter Kim N., Book 2: The Ceremonies Florentine Codex, p31v

Richter Kim N., Book 2: The Ceremonies Florentine Codex, p32v

Richter Kim N., Book 2: The Ceremonies Florentine Codex, p33v

Richter Kim N., Book 2: The Ceremonies Florentine Codex, p34r

Lora Dilas, Understanding the Ancient Americas: Foundation, Flourishing, (Yale University: Yale-New Haven Teachers, 1994,) Section 2: Part I, URL

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Tlatelolco Marketplace as depicted at Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago’, photo by Joe Ravi

Aztec Market (Tlatelolco)

While visiting the market in the city of Tenochtitlan (Tlatelolco), you will see vast arrays of merchandise and the chatter of crowds of people. A market twice the size of Salamanca selling all kinds of produce, jewelry, raw materials, and even barbers and restaurants¹ The market was not only a place to shop but also a place to gather for special events. Every 5th day was important to the Aztecs, to honor this they held 5th-day markets. On these 5th-day markets festivals and feasts would be held "When Durán accidentally asked one of his native assistants to work for him on market day, his assistant responded: “Don’t you know it’s festival day tomorrow, a festival of the market (“fiesta del tianguiz”), and that there is neither a man nor woman that wouldn’t go?" ² During these festivals there were several acts where merchants dressed up and acted to make people laugh. Specifically one of the merchants dressed as a "pustule-ridden man" and gave an act of pain to humor people.³ Even with no festival occurring the market remains a lively place where people came to gossip and interact, it was a place of leisure too. The marketplace was also a dear place for women, where they could escape gender inequality and hold some position of power. Women in marketplaces could be merchants, artisans, and even administrators who had final decisions on the market. It gave women the opportunity to gain the prestige and wealth needed to "engage in supposedly male domains."⁴ Coming to the market you would encounter a variety of people such as warriors, prostitutes, and slaves being sold, as they sing and dance to attract. However, the busy streets also provided a way for slaves to escape their elite owners. Be careful not to become a witness to their escape or else their old master could claim you as their new slave, as you now had "a stake in the event."⁵

--------------------------------------------------------------

Bibliography

Hutson, Scott R. Carnival and Contestation in the Aztec Marketplace. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2000 URL.

Thatcher, Oliver J. The Library of Original Sources. Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907.

-------------------------------------------------------------

Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., The Library of Original Sources (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. V: 9th to 16th Centuries, pp. 317-326.

Scott R. Hutson, Carnival and Contestation in the Aztec Marketplace (Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2000,) p. 136 URL.

Hutson, Scott R., Carnival and Contestation in the Aztec, p. 136

Hutson, Scott R., Carnival and Contestation in the Aztec, p. 138

Hutson, Scott R., Carnival and Contestation in the Aztec, p. 135

0 notes