Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

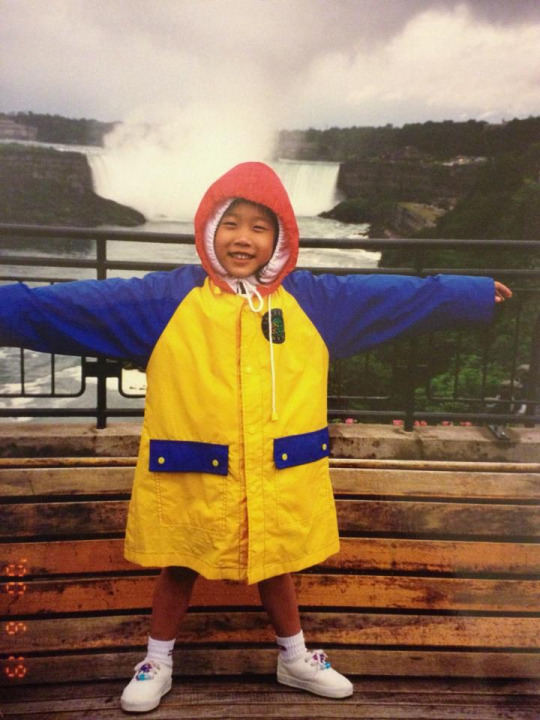

Where I Learn to Deal with Failure (or I just copy and paste choice parts of a really nice email from a former professor)

Originally featured on Korean American Story.

Beginning each morning by writing a to-do list, I feel immense satisfaction whenever I cross things off. It signals that I finished this, that I made something of my day. This compulsion for constant productivity, I am sure it stems from the way I was raised. Famously coined by legal scholar and writer Amy Chua, the term “tiger mom” refers to a parental figure with an incredibly authoritative child-rearing style—in other words, my parents. Like many other Korean parents, my mother and father were tiger parents for sure. Never accepting anything less than the best (my best was not enough, for I had to be the best out of everyone else as well), I strived to live up to their expectations.

I hold a memory from my early childhood, perhaps in the first or second grade, sitting around in a semicircle with the other school children. Having just read us a story, the teacher scribbled some questions onto the whiteboard with her thick black Expo marker. My mother happened to be in the classroom that day, along with the other parents. Her presence made my hands quite clammy, and each breath I took was so frustratingly unrefreshing. While the other kids excitedly raised their hands to answer our teacher’s questions, I sat idly by.

Under my mother’s watchful eye, I imagined the possible scenarios that could play out. If I answered a question correctly, I could earn a smile perhaps. But I also imagined what could happen if I said the wrong thing, and my mouth remained shut. I kept waiting for a question I could comfortably answer. I’ll just wait for the next one. No, not this one. The next. The one after this. The thing is, for every single question, I correctly predicted the answer before the teacher chimed in. My silence wasn’t a result of ignorance; I just hadn’t trusted in myself enough to speak up.

At the end of the school day, my mother and I walked to the car. As I watched her slim fingers turn the key in the ignition, a thick silence grew between us. Looking straight ahead, barely audible over the rumbling of the engine, my mother asked me, “Why didn’t you answer any of the questions?” But umma, I knew all the right answers, I wanted to say. Yet I was rendered mute by stinging nerves, and once again, I said nothing at all.

According to the Implicit Theory of Intelligence (Dweck & Leggett 1988), people hold one of two mindsets—growth or fixed. Following this theory, those with a growth mindset believe their intelligence can grow over time, while those with a fixed mindset believe there is a natural limit to their abilities. What I find interesting is this theory’s implications on failure. Seeing it as an opportunity to grow, those with growth mindsets react positively to failure. In comparison, people with fixed mindsets will apparently fall into the depths of despair.

To shape a growth mindset in a child, the theory stresses the importance of praising effort and not the outcome. For me, growing up in a Korean household, the outcome was all that mattered. In that classroom, in front of the whiteboard, in front of my teacher, and especially in front of my mother—what did it matter if I knew the correct answers if other people had no idea I knew them?

Fortunately, or perhaps, unfortunately, out of sheer willpower (or spite) I did meet these expectations for the majority of my childhood and teenage years. Several afternoons and evenings of my life were devoted to after-school tutoring sessions to ensure I would perform slightly better than my peers. I felt compelled to attend a high school I was not zoned for, with a bus stop at 5:15 am, to participate in their “academically rigorous” International Baccalaureate program (which is complete bull, by the way. If any high schoolers are reading this, just take AP.) I even joined the mathletes, although anything above basic algebra easily brings me to tears. I wanted all these special certificates, diplomas, and various badges of honor to my name to prove that my efforts meant something.

My tiger parents taught me that when successful, I could reap intense satisfaction. Because they reacted so well to my achievements, I ended up placing so much of my self-worth in academic validation. However, my parents skipped the lessons on how to deal with failure. Instead of an opportunity to grow, a failure was simply a failure, nothing more. It was something to brush aside and hide away, in the hopes that a greater accomplishment could mask it. As a result, achieving something felt really, really good. But failure led to equally high, possibly higher, levels of distress.

Because I based my entire identity on being the “smart one,” I had no idea what to do with myself when this label was seemingly taken away from me. Since the end of my school career, I have failed many, many times over. I failed to get a high-paying job at a consulting firm like many of my friends, I failed to get into graduate school my first time applying, and I failed to reach any of the milestones I arbitrarily decided were necessary to feel like an actual adult. Truthfully, I felt—still feel—incredibly behind. My younger self imagined I would have accomplished much more by my mid-twenties. I think I am very good at giving the appearance of being okay, but in reality, I am frantically flailing underneath the water’s calm surface.

I think the toughest lesson life taught me is that putting your best effort into something will not guarantee success. X does not ensure Y, because there are a million factors Z completely out of my control. This lesson highlights the problem with tying up self-worth in something external because I had no idea what to do once this external validation disappeared. As a postgraduate, to squeeze a few years into one short sentence—I was rather nihilistic for a while. I became so tired of trying anything at all because I was so tired of failing.

I love being Korean American. Sincerely, I do. Nonetheless, as I psychoanalyze myself, I am made increasingly aware of how certain aspects of my cultural background have, perhaps, in terms of mental health, screwed me over. It is so easy to be a victim, stay a victim, and relish in feeling bad for myself. But then what?

Not trusting myself to find the answer to my question, I reached out to many others to figure out what to do next. There was one message in particular that stuck out to me. According to my old statistics professor, Dan Player, “It’s an endless treadmill [to chase after success]. It’s really remarkable to talk to people who have achieved amazing things. Some of them are still chasing the proof that they’re successful because no matter what they do, someone else has done something better… I’m telling you, you can’t win at that “proving yourself” game.”

To “succeed” in life, I have to let go of this notion of success entirely. I have to let go of this obsession to prove to other people that I have value. I am learning and growing and (hopefully) becoming a better person, and it does not matter if other people cannot see it. All that matters is that I see it. As Dan says, I am Hojung, a “filmmaker/artist/author/scholar/general fascinating human being,” and I am fine just the way I already am.

My life has been full of so many disappointments, yes, but it is also a record full of acts of kindness, moments of grace, and dreams for myself. It is full of warm kisses, hugs full of longing, the laughter of friends, and eyes that met to share a brief moment of connection. This is my life, a life that is worth living simply because it is mine. My self-worth is something I give to myself, so it cannot be taken away, even if I never achieve something momentous or do not leave behind a huge impact on this earth once my time has passed. It is enough that for a moment, I was here. I existed. This is my Korean American story.

Extra Reading: (1) Chua, A. (2011). Battle Hymn of the tiger mother. Penguin Books. (2) Dweck, S. C., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95, 256–273

0 notes

Text

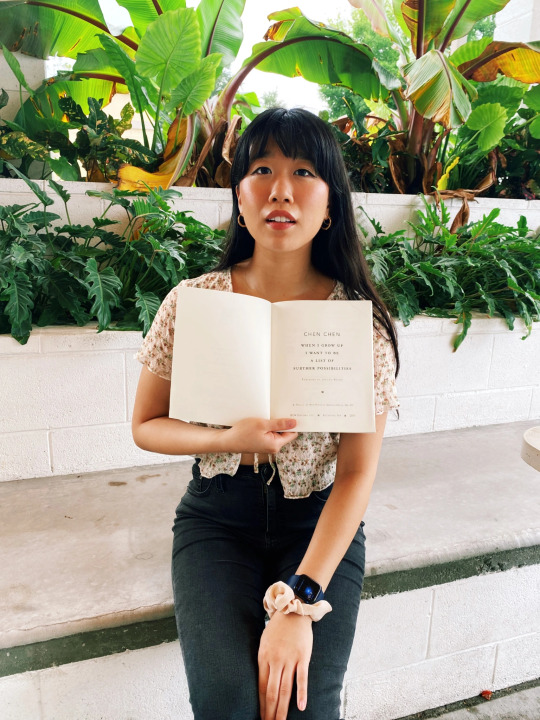

Interview with Chinese American Poet, Chen Chen, on being a representative Asian American voice in poetry

HL: Thank you so much for meeting with me! I know in another interview that you said you’re working on saying no, so I’m super grateful that you’re making time for me today. One fun icebreaker question I like to start with is, where did your parents meet?

CC: I don’t know! I should ask them. My parents are both from Southern China—I’m from the city called Xiamen. My mom grew up in the country, and my dad is from the city. So I know that.

HL: Mine met on a ski trip. My mom kept falling so my dad kept having to hold her hand.

CC: Oh my god that’s adorable.

HL: Alright I am just going to go in and start with the heavy questions about race. Do you remember the first moment that you realized you were Asian, and how did this affect your image of yourself?

CC: I grew up feeling a pretty firm sense that I was Chinese because that’s really how my parents identified and would always talk to me in those terms. I saw myself as a Chinese immigrant or a child of immigrants. I was born in China and then came to the States when I was very young. I was about four. So I had that sense of my self, that’s how I saw myself. But the term Asian? It took a while for me to feel like that was descriptive for me because it just seemed so big. It wasn’t until college that I started to think more about identifying in that way—particularly as an Asian American. It’s a term that has its own particular political and cultural history, and I learned a lot more about that in college. Before that, I didn’t know what it meant to call myself Asian American, so that changed things for me.

Just in terms of any racial awareness, I’d say from a pretty young age I was aware of that difference, aware of how different people, non-Asian people, saw me as Asian. I had an awareness of that very early on, but in terms of, you know, just the word, the terminology, it wasn’t until college.

HL: What specifically changed in college?

CC: I became interested in learning about the history of Asian Americans versus Asian people in the United States because I realized that I didn’t know that much. I was also becoming friends with other Asian American students on my campus, and on other campuses, and they were talking about the identity as this pan-ethnic one—you can be East Asian, you can be South Asian, you can be West Asian—and the idea of this political coalition community that could form with this term this umbrella term. So I became interested in learning more about the history of that.

I was becoming interested in seeking out other Asian American writers, particularly poets, because I realized that I hadn’t read that many before. You know that they weren’t taught as much in high school. There are some, but usually they’re fiction, and so I had to seek out a lot of the poetry on my own, too. I remember reading Rose by Li-Young Lee, his first book, in high school at the suggestion of an encouraging English teacher sophomore year. She recommended that I check out Li-Young Lee’s work. I remember looking at the back cover and seeing his author photo on there and being moved—Oh, here is a Chinese American, someone who likes me and is doing this poetry thing. Doing it his own way.

HL: Yeah it’s always the English teachers in high school.

CC: They just get it.

HL: Do you have any unique struggles as an Asian American, and is it amplified by your queer and immigrant identity?

CC: I think so many of us have struggled with this, this kind of invisibility, and in a lot of areas of culture and politics. So I feel I can understand why representation is such a big issue for many Asian Americans. I do think it’s not the only issue, or it doesn’t have to be the primary one. But yeah, I’d say, especially as a queer Asian American with this immigrant experience, that I have very rarely seen this kind of experience depicted anywhere. I feel motivated to depict my own experiences in my writing because of the lack because there’s been such a huge lack.

HL: I went to the library and I specifically asked for Asian American authors, and the librarian could only name Amy Tan and no one else. It was frustrating for me.

CC: It feels like we’re always fighting for that recognition. Other non-Asian people are always behind, either catching up or they have static knowledge about Asian American literature. It just stops developing at a certain point—after they’ve read one author, or two, maybe, and then that’s it. It can be frustrating to see that because there’s such a wealth of literature that I think people are missing out on.

HL: We only read boring old dead white men in high school and college.

CC: So many people just did not move on. I want people to be more curious and also take the initiative to educate themselves because I just think it’s so exciting and enriching what’s happening in Asian American literature.

HL: Do you feel like you feel stuck in your identity as an Asian American poet? For example, I remember when I was reading Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings, a collection of essays, she talked about how she felt like no one would take her seriously as an Asian poet.

CC: I do think that some of that has changed in recent years. I feel very lucky to have come up as a poet when I did because there was already a lot more going on in editing and publishing. There were a lot more books by Asian American poets, fiction writers, and non-fiction writers. Just in the last ten years, there’s been an explosion. It’s been great to see that. I didn’t feel as much pressure when my book came out. I didn’t feel like I needed to speak to the Asian American or Chinese American experience in a particular way, which I feel very fortunate about.

In the past, I think there was a lot more pressure. I mean tokenizing still happens, but I think there was a lot more of that. And so there was the sense that to call yourself an Asian American writer can only mean one thing, that you have to represent a whole culture, a whole experience, in a simplified way and a palatable way, mainly for a white mainstream audience. I think that pressure has lessened, to some degree over the years, so I feel fortunate about that.

And also just for me, I feel like identity is just so expansive and so complicated. I feel like I’m continuing to learn. I don’t feel like I can definitively say that being Asian American means X, Y, and Z. Because for me it changes too, at different points in my life, my relationship to that term. On thinking of myself as an Asian American writer, I embrace that label. I don’t find it restrictive really, because there are so many different styles and approaches and subject matter that you could call Asian American literature.

HL: One thing I have been dying to ask you about because I identify with it so much in your debut collection, you talk a lot about your fraught romantic relationships with white boys. I remember in elementary school when I would have a crush on the white boys in the class, I would just automatically assume he wouldn’t like me. I think I’m cute, but I’m not white, so I just automatically assumed he wouldn’t like me. I wanted to ask about how we don’t meet Eurocentric beauty standards. How did that influence your self-image?

CC: I think I internalized a lot of racism, because of that very issue—feeling like I wasn’t up to those beauty standards, those Eurocentric beauty standards, and being socialized to seek the attention of white men. So many of us are socially conditioned to do that in this culture. It’s taken me a long time to examine that, and I think I’m still processing it and examining it and unlearning certain things. Writing has been a way to process those experiences and those emotions. And, yeah, I feel especially in recent years, I’ve become a lot more self-loving. A lot more just embracing as well, of being Asian.

I used to be very self-conscious and embarrassed about how I looked in photographs and I would beat myself up about it, feeling like I’m not attractive or I’m not good-looking in the standard ways. But I love taking selfies. I love posing in photos. I realized that in the past, I used to always make a funny face sort or strike a funny pose in photos. That was my way of getting around my discomfort. But I was looking back on it, and I realized that I was also trying to make other people comfortable. I was overcompensating for this anxiety and this insecurity that I had. And so now, I mean I still love doing funny things in photos, but I feel a lot more comfortable now just taking a regular picture and just looking like myself in photos. That’s taken a long time, to become more comfortable in my own skin.

HL: I think I also used to do the same thing actually, like I would purposely try to make myself look bad in photos so that no one else could be like, oh, that’s not a good photo.

CC: You kind of sabotage it. Or you try to change the tone of it in a way so that it can’t be disappointing because it’s already funny or weird.

HL: One more poetry question! As a poet, you tend to capitalize on really striking emotional moments in your life. Your poem, “Race to the Tree,” was very emotional for me to read. Is there any cost to tapping into this vulnerability? Are you ever afraid to release a poem into the world?

CC: Yeah, I do get nervous. I remember before this book was published, the first full-length book, I published these two chapbooks—much shorter collections—and the first one set the car on fire. It’s extremely autobiographical, personal poems, a lot about my family, a lot about being an immigrant, and a lot about sexuality. An earlier version of that poem that you just mentioned, “Race To The Tree,” is in that chapbook. I remember getting the galleys for that chapbook—the physical copy that the publisher sends you. It’s not the finished book yet, so it didn’t have the cover on it, but it was bound. Holding it in my hands for the first time, I vividly remember freaking out. Both in a good way, I was super excited, but also I was super nervous at the same time. It hit me that, oh, this is gonna go into the world. It’s still a small publication—this is a chapbook from this tiny press, but still, it just suddenly felt very real.

I had a similar feeling with the first book, although by that point I’d gotten used to it a bit. It takes some practice. In writing, I often tell my students this can be a really good sign. If you do feel scared about what you’re writing about or how you’re writing about it, it can be a good sign that you’re tapping into something complicated, not neatly resolved. It’s still this messy set of emotions that’s brought up for you. So, because of all that, usually, it leads to some good writing. But at the same time, I advise people to take care of themselves as well. Don’t push it if you’re not ready to, but if it feels urgent to you to go there, just allow yourself to do it in a certain way where it doesn’t harm you, ultimately, to be writing about those difficult subjects.

HL: When I write I want to tap into old relationships that ended badly, but I don’t want to annihilate people along the way. Do your parents ever get upset that you mention very intimate moments with them in your poems?

CC: They haven’t really mentioned anything. I think it does bother them sometimes, but I feel like especially at this point they get that I am my own person. I’m an adult now. I’m saying making my own choices. But I guess I always try to make it clear, too, that I’m trying to tell my own piece of the story. You know, like they’re often in the story that I’m writing about, but it’s my personal, subjective experience of it. I try to always focus on what has been my experience of our relationship—my relationship with them, rather than other aspects of their lives which I don’t feel I have as much access to. That’s where the focus is, and I hope that they understand that.

HL: Wow I learned so much about you and your writing, and it was very cool. Thank you! Can we take a selfie?

CC: For sure!

HL: I’ve been telling my friends about it, and they’re like: “Oh my gosh that’s so cool you get to interview Chen Chen.” How should we pose? What should we do?

CC: Let’s do one serious and one more playful. So let’s do the serious one first.

HL: Okay what should we do for playful?

CC: (Displays peace sign.)

HL: Thank you Chen! CC: Thank you for your questions! It was so nice to talk. HL: Do you have any parting words of wisdom? What’s your secret sauce to life? CC: Sleep. Take naps if you feel like it. Eat good snacks. I feel like I’m turning into my mom a bit, because now what I want to tell everybody and tell myself, remind myself, is that you have to take care of your body, before you can do other things—to make sure that you’re eating well, getting enough rest. Because I used to not take that so seriously, but now I feel like it’s really important. HL: Now that I’ve reached my mid-twenties, I feel like I can’t get away with stuff that I used to in the past. CC: Yeah, I think it’s you just feel better all-around when you’re not trying to push through things all the time, and you’re making time to take care of yourself. HL: Alright, so take naps and eat good food. Well, I hope you have a wonderful rest of your day! CC: Thank you! Yeah! It was great to talk. HL: Ah I don’t know how to end this. CC: Yeah on Zoom it’s always kind of funny. Alright, see you!

0 notes

Text

Hi, I'm Hojung.

Hojung Lee (b. 1996, Seoul, South Korea) is a writer residing in Florida. She graduated with a BFA in Public Policy & Leadership and Studio Art with a film concentration from the University of Virginia (2019).

0 notes