Note

:As such, for me, Aegon ranks alongside Quentyn and First Book Sansa in terms of the author’s angriest writing about his own genre" could you expand on the sansa part

Sure! This is something @nobodysuspectsthebutterfly and I talked about at the last Ice & Fire Con: Sansa as a stand-in for the fantasy reader, specifically an uncritical reader. Her fall-into-knowledge over the course of AGOT is so dramatic and devastating because she starts out in a bubble, and that bubble is explicitly fueled by songs and stories. In other words, fantasy has left her unprepared for the likes of Cersei and Joffrey. Sansa’s been trained to look only at the surface, and not question what goes on beneath it. By demonstrating that she needs to ask those questions, the author is encouraging us to do the same. As such, after her beloved handsome prince forces her to watch her father executed after promising her that he would show mercy, Sansa is “reading” the world around her differently, wondering how she ever could have loved Joffrey.

What makes this more than a miserable grimdark grind, however, is the conclusion Sansa draws from this experience. She does not become Cersei, determined to imitate the unjust systems that have brought her low; she does not become Littlefinger, thinking only of what she is owed and creating more victims in the process. Instead, she gradually realizes that *she* must live up to the values expressed in the stories and songs, even–especially–if the world around her (particularly the institutions and individuals in power) does not. “If I am ever queen, I’ll make them love me,” for example, or even more powerfully, “he was no true knight.” The latter is what sparks Sandor’s own gradual reformation, because what Sansa is saying there is that the corrupt institution of knighthood, that which anointed Gregor and thus convinced Sandor that the values of knighthood he’d worshiped were a lie, has no monopoly on what it really means to be a true knight. That idea is a core theme of GRRM’s writing in this universe, from “a knight who remembered his vows” to “a king who still cared,” from “my people…they were afraid” to “no chance, and no choice.” For me personally, more than anything else, it’s what makes Sansa Stark such a compelling character.

678 notes

·

View notes

Note

Have you ever posted a list of book recommendations? I’d like to know what novels sit alongside ASOIAF for you other than The Name of the Wind obvi.

I’m sure I have but why not do it again, right?

The Lord of the Rings - J.R.R. Tolkien

Nineteen Eighty-Four - George Orwell

Books of Blood Vols. 1-6 - Clive Barker

Hitler: 1889-1936 Hubris & Hitler: 1936-1945 Nemesis - Ian Kershaw

Nixonland & The Invisible Bridge - Rick Perlstein

The Diary of a Teenage Girl - Phoebe Gloeckner

Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth & Acme Novelty Library 20: Jordan Wellington Lint - Chris Ware

Black Is the Color & Laid Waste - Julia Gfrörer

Black Hole - Charles Burns

The Furry Trap - Josh Simmons

Pim & Francie: The Golden Bear Days - Al Columbia

The Stand, It, Night Shift, Skeleton Crew - Stephen King

Conan stories by Robert E. Howard

Horror stories by H.P. Lovecraft

Love & Rockets - Gilbert & Jaime Hernandez

Gast - Carol Swain

Asthma - John Hankiewicz

Garden - Yuichi Yokoyama

After Nothing Comes - Aidan Koch

Or Else #2/Gloriana - Kevin Huizenga

The Dark Is Rising Sequence - Susan Cooper

Earthsea Vols. 1-4 - Ursula K. LeGuin

Sumo - Helmut Newton

On Immunity - Eula Biss

Carnal Knowledge - Malerie Marder

Celine Dion’s Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste - Carl Wilson

Dreaming the Beatles - Rob Sheffield

Catching the Big Fish - David Lynch

Film Art: An Introduction - David Bordwell & Kristin Thompson

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

Considering Spielberg is your (second?) favorite director, do you have any kind of ranking of his filmography? (If so, I hope you give Empire of the Sun the high marks it deserves. It's the quintessential Spielberg film! A boy's own adventure story that gets eaten alive by a war drama!)

*rubs hands together*

Ok, so, only ones where he was in the director’s chair; none of even those producer’s credits where you can feel his indelible stamp on the final product, so no Goonies, Gremlins, Poltergeist, or Back to the Future. Even then, I’m leaving out a lot, so honorable mention to Lincoln, Schindler’s List, Saving Private Ryan, Catch Me if You Can, War of the Worlds, The Color Purple, Bridge of Spies, the two worthwhile Indy sequels…

10. Jurassic Park

Start with the gaze upon himself: Jurassic Park as a $63 million self-portrait released on the exact tipping point of his career. John Hammond and Steven Spielberg’s miracles are one and the same: one brings dinosaurs back, the other convinces us they’re real. One uses DNA, the other uses CGI. When the characters stare in wonder, they’re meant to mirror our own at the imagery; when Jeff Goldblum mutters “that crazy son of a bitch actually did it,” he’s speaking for an entire industry once again forced to up its game by a Spielberg Miracle.

Our protagonist, however, is shitty with computers, so Alan Grant terrifies a child the old fashioned Jaws way: with a prop (a raptor claw) and his imagination. Hammond whisks him away from that to a world where one can press a button and make yourself appear on screen, mirroring how Spielberg has done the same with Hammond as his craft has evolved from malfunctioning sharks to CG velociraptors. The heart of the film comes when this giddy wonder in the possibilities of “we have the technology” is soured and our author avatar is left disillusioned and afraid, eating ice cream in a room full of merch he’ll never sell (but Spielberg will), telling Laura Dern about how he started off with a flea circus. That, right there, is a metaphor for moviemaking, and specifically Spielberg’s brand of it: pulling invisible strings to make us think that impossible things are real, to make belief believable.

Above all, Jurassic Park is afraid for the kids. Another perfect metaphor for the meta-tastic whole comes when the T-Rex crashes down through the car roof, only glass separating him from devouring the children; their hands are desperately keeping the monster behind the rectangular transparent plane, on the screen, even as Spielberg/Hammond’s tech is so real it threatens to burst right through. “He left us!” one kid wails about the character representing the studio weasels. “But that’s not what I’m gonna do,” Alan Grant whispers, half in shadow, blue eyes ablaze with a promise he didn’t know he was going to make. He can’t keep it. There are monsters in the kitchen. Spielberg’s next movie, released only a handful of months later, is Schindler’s List.

9. Duel

Such a seam scratches the tape; rewind, start again. Where did this begin? On TV, in the backseat of a car, backing out of the garage. Duel is the world’s most accomplished demo reel, cinema stripped down to its bare minimum to let the director’s preposterous surplus of talent shine through. It’s about a man (named Mann, both appropriate and touchingly pretentious) who pisses off a truck driver we never see, who then chases our protagonist with lethal intent, and that’s it.

And that’s all Spielberg needs. What follows is the future, a steel-shod gauntlet of precise camera angles and insidious sound design that builds the bridge between the B-movie and the blockbuster. By the end you feel spent but sated, as if every possible creative drop has been wrung out of the slim scenario. It’s nothing more nor less than the finest Roadrunner & Coyote episode imaginable, to the extent that George Miller was clearly reaching back to it for inspiration again and again in Fury Road. Indeed, while Duel is set in the modern day, Spielberg needs no trickery to make the antagonistic truck look positively apocalyptic.

It’s such a vivid example of the medium’s unique possibilities that you have to stop to remember that it was made for TV. And then you stop to think that he was only 24, same age Welles was when he made Citizen Kane. Lofty comparison, I know, but Duel proves it’s not what your movie is about, but how it’s about it that counts. Spielberg made it look easy, and so everyone followed. The road goes ever on and on…

8. Munich

…until it doesn’t. No exit.

Munich is the culmination of Spielberg’s Blue Period, his great here-comes-another-bloody-century trepidation, punctured by Stanley Kubrick’s death and 9/11. The former gave birth to A.I. Artificial Intelligence, and the movies about closing doorways and agonized faces that followed. The latter palpably haunted Spielberg’s projects in its wake: even Minority Report, a script written years earlier and adapted from a decades-old story, was uncannily timely in its portrait of overreaching security and law enforcement built to placate (and control) a population reeling from loss. Then came the director’s outright Twin Towers Trilogy: The Terminal, War of the Worlds, and Munich, addressing the event from different angles and through different filters. Of course, the intriguing and emotional setup in The Terminal’s opening minutes, framing post-9/11 bureaucracy as fluid chaos eating away at the state from within, quickly gives way to disappointing inanity. And while I maintain that War of the Worlds is absolutely perfect as an on-the-ground recreation of 9/11 as an alien attack for the first 50-60%, things go downhill fast once Tim Robbins shuffles onscreen.

Munich is the one that actually has the courage of its convictions, in large part because it’s about the director and protagonist alike breaking down in tears and admitting they don’t know what to believe anymore. Every set piece unfolds with a quiet chill and ends with you contemplating mortality. It’s a deliberately non-thrilling thriller. The ideology dissolves, not in neat bromides but in the day-to-day realities of ending human beings. Revenge fills you with fire, hot and bright, and then turns sour in your mouth. Narrative strands cross and recross, and the film’s inciting event, murder before the world’s watching eyes, sinks into that abyss known as Context.

By the end, you don’t even know what you’re fighting for anymore but your family, and you’re haunted by the knowledge that your kids will be fighting the same damn fight. The last thing to be corrupted, then, is the dinner table. Our protagonist begs to break bread with his handler, and the final word of the Blue Period is “no.” The camera tilts over to the Twin Towers, their loss contextualized as just another curl of a horrorshow helix, and the exorcism is complete. The anger and grief has largely vanished from Spielberg’s work since, as he’s settled into a comfortable John Ford mode. He left his questions here, unanswered.

7. Minority Report

If A.I. was Spielberg’s 2001, a millennia-spanning epitaph for humanity and a glimpse of what we leave behind, Minority Report (following the Kubrick trajectory) would be his Clockwork Orange, stepping down from the stars to gaze with cold horror on the things we do to one another with power. In the future, three young seers see crimes before they happen, enabling the state to lock people away for crimes they haven’t committed in the name of wiping out crime for good. Indeed, this fleet fluid fever dream makes explicit visual reference to Clockwork’s Ludovico scene (see above). In Spielberg’s memory machine, though, the image of an eye forcibly kept open by metal claws takes on a meaning beyond social and political analysis, though those are certainly still in there. It’s something more spiritual: Minority Report is about divine sight in a postmodern age.

Our protagonist’s rival went to seminary, his own men tell him they’re more priests than cops, but Tom Cruise’s John Anderton can’t bring himself to recognize the Spielberg Miracle at work here. The larger moral revelation of the “precogs,” the framing of their ability to see crimes before they happen as a techno-noir version of Biblical prophecy, is lost on Anderton because it can’t bring his son back. For him, that the future is known points to the futility of human existence. If there’s no free will, if we’re all doomed to perpetually fall in a fallen world, what’s the point?

And then one of the precogs asks him: “Do you see?” So begins the murder mystery that will see him accused of a future murder, that of the man who ostensibly killed his son. Anderton chooses mercy, only for the man to grab and pull the trigger because it’s all a setup to prevent Anderton from learning the truth about the precogs: they, too, are children stolen from their parents, all our characters trapped in a Möbius strip of loss they can only watch unfold, again and again, as if on the film’s countless screens. The images have been manipulated to hide the truth, the divine vision sullied by contact with the greedy exploitative systems of the Blue Period. But our detective finds the truth, and an existential triumph in making the right choice even if he can’t change the outcome. I’ve always taken the happy ending, a startling glimpse of green after a movie of blues and grays that look etched in stone, as just another vision. Closure is there, your family is there, in the future, in the past, just out of reach, smiling back at you. It hurts to look, but even as your eyes are torn out and replaced, you can’t look away.

6. Raiders of the Lost Ark

Well now, see, this one’s a tad criticism-proof by design, being as it is smelted and shaped to get under your defenses. “Disarming” seems like a strange choice of defining adjective for this most white-knuckled of action/adventure movies, but for all the staggering moviemaking skill on display, Raiders is ultimately a puppy shoving its nose under your hand. Given the slightest opportunity, it will make you love it. Fun is its religion, so deeply felt and communicated is the generous desire to entertain, rooted in the pulp serials that first lit the fire in its makers’ bellies to create.

And that fire again burns hot and bright, which is Raiders’ other secret magic trick: underneath all the cleverness, the jokes within jokes and setpieces spilling into ever more elaborate ones, the sense that every single moment was designed to make the rest of the genre look paltry and stingy by comparison, what happens at the end is nothing less than the very specifically Old Testament God stepping in to fry Nazis’ faces off. It’s the Ghostbusters trick of grounding helium-high hijinks in metaphysical forces that are not in any way kidding around. Our action hero, at the climax of the movie, is simply the one who (in an inverse of Minority Report) is smart enough to look away. So many Spielberg movies boil down to a shaft of divine light, and sometimes the light burns.

Then came the bizarre, hallucinogenic Temple of Doom and the sturdy, winning Last Crusade and that fourth one we don’t talk about, but they’re all in some way reactions to the nigh-flawless original. All you can do is go back, wearing the leather deep, Indy ageless, his eyes blazing shut against the light.

5. Empire of the Sun

Equally criticism-proof, but for the exact opposite reasons. This is the one no one can quite explain. Spielberg isn’t telling; he might not have any more idea than the rest of us. It shares certain themes with the rest of his work, especially regarding how children process the collapse and change of their world, but the similarities are strictly on paper. It feels different. I don’t what it…is. What it’s for. What it means. These sound like bad things, but they’re not. Empire of the Sun is utterly arresting, every bit as much as those canonized Spielberg classics of which anyone can explain the appeal. It’s just that it unfolds like a dream, and I’m left grasping after it in the same way. It might be one of the more accurate adaptations put to film in only that it feels so much more novelistic in its thrust and tone than most.

What can be pinned down is a series of images and sounds about the fall and occupation of Shanghai by Japan in WWII, told from the perspective of the naive sheltered son of a British emissary. Our hero is played by Christian Bale, in what might be my favorite child performance. To the extent that Empire of the Sun is about anything beyond the experience of watching it, it’s about his breakdown, and that’s what grounds the dreamlike style: we’re watching a bubble burst. Death and decay unfold out of the corner of his eye, like a memory he can’t quite bear to fully recall. His childhood vanishes when he shrieks surrender at anyone who will listen, trusting the rules to snap back into place and the world to make sense again, only for the collapse to continue unabated.

It’s made out of smoke and corners and quiet sadnesses. It’s runny, like an egg. I dream about it sometimes. You should watch it if you haven’t.

4. E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial

*harrumphs, wipes eyes* so um uh my name is Emmett, you see, and it begins with a….an ends with a….shut up.

That’s the point, though, of the movie: identification so strong that it almost kills you. E.T. is love, that’s all. All of it is here, from pure warm glow to heart stopping loss, swept up in imagery and sound that seem to positively hum with rich rueful feeling. Much has been made of how much of the movie is shot from a child’s POV, but everything about the movie operates on kid-logic. ET himself, for example: botanist or pet? Both. The connection he forges with Elliott swirls all such categories together. Elliott needs this, is yearning for love so badly, and even when it hurts, he’s more alive than he was before, with Dad gone.

But what makes E.T. different from, say, Star Wars and Harry Potter is that our hero only gets a taste of this other world, his fingertips brushing against magic as he passes it in the night. The gold-and-purple-brushed cinematography and the ecstatic, eternally swelling score sweep the profound and mundane together as one, bike rides and trick-or-treating and a psychic connection with an alien, yet the narrative eventually teases them apart like a sad parent forced to tell their kid that the dog is dead, and what “dead” means. ET returns to life, the definitive Spielberg Miracle…and then he leaves. Elliott will go home to his melancholy, frustrating life. School is still hard. His emotions still confuse him. Dad is still gone. The final shot of his face is not one of wonder, but maturation. It’s the moment Elliott grows up, and it’s the very definition of bittersweet.

What do you do, when you’ve loved and lost? You go home, you play with your toys, you send letters into Weird Things and Such SF Monthly, you make movies in your backyard, and you watch the skies….

….until they come back.

All of them.

3. Close Encounters of the Third Kind

I smiled just typing the words. I whispered them to myself, Close Encounters of the Third Kind. This movie is a lil shining red ball dancing in my eyes; it is glee given form, a rainbow-colored pony ridden by a Willy Wonka-suited Care Bear on twenty tabs of LSD. The last half-hour, all glowing light and warm noise, earns the cliche: it makes you feel like a kid again, in the best possible way. After a movie’s buildup of wonder and terror, the sight and sound of a colossal lit-up mothership cheerfully BWAMMing out a melody is so cathartic that it’s impossible to sit still.

As with Raiders, though, it’s worth digging into the movie’s layers to understand where that light is coming from, and what it costs you to look at it. Close Encounters is a movie about communication, of course, from the alien lights to the translator forever accompanying Francois Truffaut (a filmmaker who knows a thing or two about capturing kid-logic on screen). It’s a movie about the fragility of family life in the face of the unknown, hence that devastating scene around the dinner table: something’s wrong with Dad, a subject near and dear to the director’s heart.

But above all else, it’s a religious movie, the religious movie. It’s about rushing upwards, and leaving all else behind. Roy Neary sees a divine light in the sky, and can’t reconcile it with the life he was living. He obsessively recreates his vision in idols, chases it across the country, driving his wife and children away in favor of his fellow prophets: here are my mother and my brothers. And the sting in that gorgeous symphonic ending’s tail is that it’s so good that Roy sheds this mortal coil to join them in the heavens. Spielberg has said that if he made it now, he wouldn’t have let Roy get on that ship. And when you look at E.T. or the movies he made from Schindler forward, it’s clear why: in joining the interstellar flock, the man-child left his family to the wolves. By the time Roy/Eliot came home, his skin had sagged, his hair had gone white, and his children were waiting for him with eyes that cut.

And what do their movies look like?

2. A.I. Artificial Intelligence

The ultimate deconstructed fairytale; a honeyvelvetacid-glazed gaze into a heart-shaped abyss; Kubrick a darkwinged angel looming over ET’s crib, brushing a final tear away from his metallic eye…

So does Steven Spielberg, our flesh and blood Peter Pan, grow old and tell the children he lied. The monster is inside the house, inside your head, and inside the stories. At the core is a child’s innocent love for his mother…programmed in him, by her, a debt she cannot and will not repay. “His love is real, but he is not.” Pinocchio but for robots, A.I. takes its sci-fi trappings as a launching pad for a guiding philosophical question: “if a robot could genuinely love a human, what responsibility would that person hold towards that mecha in return?” The boardroom exec who poses that question pauses, almost bashful to ask the next one in a room full of people who treat the abuse of robots like a joke or a PowerPoint presentation, and then proceeds: “it’s a moral question, isn’t it?”

It is indeed, and for David’s adoptive family, the answer is none. He is abandoned, and chases his Blue Fairy and his happy ending across the apocalypse. As his fellow robots are torn apart to the cheers of the crowd in front of him, as his entire environment upends his hardwired fairytale logic into a sleazy neon-and-smoke nightmare, as his companion Gigolo Joe warns him presciently that “they made us too smart, too quick, and too many…they hate us because they know that when they’re gone, all that will be left is us,” David keeps looking for the Blue Fairy to turn him into a real boy so Mommy will love him again. He has no choice. His brain literally will not let him do otherwise. There is no will to power here, no core he can call upon to upend his puppet masters’ plan and prove himself Human After All. All he has is love, and they’ve used it to enslave him: at journey’s end, he finds his maker, who reveals that everything post-abandonment was staged to test if his love held. It did, and as such that love is now a corporate-approved field-tested quality-assured Feature that can be passed onto the hungry customer. This is not a Hero’s Journey, because you are not a person. You are a thing, and this is a product launch. David sees a dozen faces like his, stretched on a rack and ready. There is a row of boxes. They have David’s silhouette on them. All of a sudden, one starts to rattle and shake…

In the face of this existential horror (“my brain is falling out”) David promptly chooses suicide, whispering “Mommy” as he jumps from the statue he saw in his first moments. Down in the void, he finds the Blue Fairy and prays to her for millennia, but she cannot answer his eternal plea. She is a statue. An image, nothing more. She crumbles into a thousand pieces in his arms. He finds his mother, too. She is a fake, a digital mirage. Future robots create a simulacrum of her, as David himself was a simulacrum to replace her comatose son, designed in the image of his creator’s dead son…and of course, he cannot tell the difference. He gets his happy ending, on the surface. Underneath, what’s actually happening is that he’s an orphan who will never grow up being shown a movie and told everything is going to be all right. He thrusts his fists against the posts and still insists he sees the ghosts…

…but it doesn’t matter how much he wants it, that is not his mother and his mother never loved him. We know these things even if he doesn’t. He claps because he believes in fairies, forever, eyes and smile frozen, waiting for them to appear, any second now. This is Spielberg showing you a brain on Spielberg. David followed Story over the waterfall’s edge, and now has only time’s vasty deep into which to shout “I love you” and convince himself the echoes are his make-believe savior and his long-dead mom. There is only the water that swallowed up Manhattan, and then the world, and him with it…

Wait.

There’s something in the water.

1. Jaws

To borrow from Alien, the closest thing it has to a peer: Jaws’ structural perfection is matched only by its hostility. You could just call it the perfect movie and walk away, except that if you try the floor tilts up beneath you and down you go into the mouth, the most abyssal maw in imagination’s history, and those black eyes roll over to white and you beg for more.

Run down the pedestals at the Movie Museum: Citizen Kane wants you to breathe in a life. Rashomon wants you to question how storytelling works and what Truth actually is, or if it exists at all. Jaws wants to eat you. Not the characters, you. That’s what Spielberg figured out how to do, and the entire industry reshaped itself around copying him: tonal immersion so absolute that he could make the audience feel anything he wanted, on a dime. Hitchcock played your spine like the devil on a fiddle; Spielberg is a rainbow-wigged mad scientist strapping you on a rocket to the sun. He created his own genre, and it’s the one that still dominates the medium in every corner of the globe. With a shark. A shark that, as a prop, did not fucking work.

Details? How do you pull one strand out of a web like this one? I can only say “perfect” so many times, but I mean it. Shot for shot, line by line, beat by beat. Every domino falls. The calm moments and the funny ones and the frantic blood-soaked ones, everything is earned. As with Raiders, the highest compliment I can pay is that other movies taste like shit for a month afterwards. When I hear the word “craftsmanship” I do not think of cars or cabinets, I think of Jaws. It feels hewn.

The numbers came later. The myth, the legend, the pale imitations, the bad sequels, the ripple effects, all secondary. What Jaws is, is sensation. It cannot have been made, surely, it hatched. It was never launched. It will never fall. Smile, you son of a–

77 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why Victarion is so awesome?

Heh, I know, right? On paper, Victarion Greyjoy seems like the dullest character imaginable: unchanging, undramatic, unreflective, and deeply unpleasant. Yet I love his POV chapters and have never run short of things to say about him. I think Victarion’s characterization is a triumph of tone and context.

Tonally, GRRM’s masterstroke was framing Vic’s blood-soaked circlin’ of the abyss as an extremely grim joke, granting us some measure of catharsis while being trapped in this particular head by encouraging us to laugh at him. The contrast between Vic’s puffed-up self-conception and his transparent inability to understand when he’s being manipulated makes me chuckle as I wince. This black-comedy gambit works in large part because it’s rooted in the Iron Captain’s dynamics with much smarter people. Both Euron in AFFC and Moqorro in ADWD realize they’ve got a useful tool on their hands, and the primary difficulty they face in wrapping Vic around their respective li'l fingers is refraining from bursting into laughter. The monkeys have no such compunctions, and their cackles are meant to cue our own. This stooge thinks he’s a supervillain! “Blind to the tentacles,” indeed.

As for the context, the Crow’s Eye and the Black Flame are able to so effortlessly hack into Vic’s psyche in part because they’ve got genuine metaphysical heft in their corner, their third eyes wide open, whereas he’s clinging to a racist revanchist mythos about how stealing shit makes you awesome. In this way, Vic becomes a vessel for ideological diagnosis; he is an avatar of the Old Way, and the Old Way cannot protect him from wizards. It can’t protect him from anything: the injury that nearly kills him is self-inflicted, as the colossal fool grabbed his enemy’s sword in his fist for no reason beyond wanting to be the most pirate-y of all the pirates. He thinks it’s badass, but it’s pathetic. To zoom out from the micro to the macro, this ideology has left the Iron Islands an impoverished backwater that regularly gets its collective ass kicked by the mainland whenever the latter gets sick of being raided. Both of Balon’s wars were complete wastes, a stupid and selfish ruination inflicted in the name of a cultural self-conception that is not only fanatically hateful and violent, but utterly unmoored from material reality and the lived lives of the Ironborn.

That’s one of the main reasons Euron won the kingsmoot, and it’s the reason Victarion lost it: underneath the south-shall-rise-again bluster, most of the captains and kings know by now that “all you’ll get from me is more of what you got from Balon” simply is not enough. The “mighty pillars” are falling. The myth is dissolving. All of Westeros is dying…

And to zoom back into the micro, that collective decay and ennui is given individual form in Vic’s inner monologue. What makes him work as a character, and especially as a POV character, is that he is deeply unhappy. He does not know why. He keeps trying to fill the hole inside with rape and murder and telling himself he’s finally pulled one over on Euron (as if), never wondering if it’s his lifestyle and ideology that are making him unhappy. Victarion is bored because being a villain is boring. Spending your days hitting people from behind with folding chairs and then taking their stuff is not only violent and cruel, it’s shallow and unsatisfying. It doesn’t even work for him. Euron represents another flavor of evil altogether: he just wants to ride to Valhalla on a sea of screaming souls, and this makes him perfectly content. But Victarion believes in something, and that something has failed him, and he doesn’t know what to do about it. I think he’s going to die before he learns.

329 notes

·

View notes

Note

On Rick and Morty: what the heck is the point of Jerry?

Jerry is there to show what happens to Morty if he never meets Rick, as well as to throw Rick into sharp relief. I did love that moment in “The Whirly-Dirly Conspiracy” (aka RICK AND JERRY EPISODE!) when Rick pointed out that Jerry, too, manipulates people–he just does it in a passive fashion.

43 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why don't the adult versions in IT(the book) not remember what happened to them as kids

Accidental double negative, I’m guessing :) as to why Bill, Bev, Ben, Eddie, Richie, and poor Stan don’t remember the deadlights until Mike, the one who stayed, calls them all to tell them the murders have started again and to ask them to come home like they promised they would, home to Derry, home to the killing floor, to fight It once more…there are several reasons why, which tie into the multiple interwoven narrative layers upon which It is built.

The first is sheer trauma. As kids, the main characters were hunted by a shapeshifting monster preying on their worst fears. They faced death, again and again; they spent some of the most formative days of their lives mired in horror. As such, after escaping Derry, they shoved what they’d seen to the farthest corners of their brains, where it lay in wait. Part of what makes It work despite the bloated overreach and some truly terrible storytelling choices (the preteen gangbang being only the most infamous) is the focus throughout on traumatic remembering, on skeletons crawling out of closets. Our heroes basically have PTSD; they have repressed their memories of It in order to cope, and Mike’s calls bring them back to the light. All six of them suffer for it, but Stan suffers the most. He was both the most rigid and brittle of the Losers’ Club and the one who understood best the nature of what they were fighting (it’s later revealed that he was the only one of them who realized as a child that It was female and could bear progeny). Remembering that, being called back into that, is more than Stan can bear. It shatters his sense of a proper ordered universe, and he kills himself rather than face that. Throughout It, King emphasizes the primal power of the kind of “children as prey” fairytale on which he’s riffing. In this case, the monster in the basement is so traumatizing that Stan chooses the abyss. “It,” then, comes to signify that thing you’re trying to forget, that part of yourself and your past that you’ve buried, that thing, that it, forever in the back of your thoughts and the corner of your eye. I would go so far as to argue that King built It around drip-by-drip traumatic flashbacks in part to evoke what abuse victims go through: the agony of remembering, bit by bit, what was done to you when you were alone and afraid.

The second layer is the strong sense that these six made an unconscious deal with the devil–they sold out their memories, and made out like gangbusters. Mike quietly notes that the six who left turned out far more financially and professionally successful than him, the one who stayed in Derry and (thus) held onto his memories. When he calls them, they’re forced to acknowledge how much of their adult lives flow from the childhood they can’t consciously remember. Bill, a popular horror author (and a transparent stand-in for King himself), realizes that all along he’s been writing about Georgie, his little brother who was killed by It in the book’s iconic opening scene. It’s only when Bev and Eddie are called home that they really face down the undeniable truth that they married their father and mother, respectively. (That’s pretty reductive in execution, but it fits the theme well.) Stan’s been riding a spooky wave of luck for years, recalling only deep deep down why that might be (“the turtle couldn’t help us”). Ben’s a hotshot young architect who shed all those pounds, but he also swiped the look of his controversial new communications tower from the design of the Derry Public Library, his refuge as a lonely child. He’s rich and famous and handsome, and yet he keeps flying west because he’s so afraid of the darkness catching up to him, not because he remembers what’s waiting in the shadows but because he doesn’t. After Mike calls Richie, the latter notes in a daze how terrifyingly easy it would be to tear up everything he’s accomplished since leaving Derry. They are so very fragile, these American dreams of ours, and they’re rooted in nightmares.

Indeed, the third layer goes beyond the personal to the political. As King has a one-off character note early on, It is Derry. “Somehow, It got inside.” The monster has been feeding on and encouraging the town’s worst instincts for years, happily soaking in the violence whether it’s motivated by racism or homophobia or bloodthirsty revenge. This is where Mike, my favorite character in the book (by a notch above Stan the Man), takes center stage. As the town librarian, he devotes himself to unearthing Derry’s singularly ugly history, and it is he who discovers the pattern of It. Every generation, It emerges to take Its toll; Derry is its “private game reserve.” As Mike asks: “can an entire town be haunted?” This is something arguably even more traumatic for our heroes than the memories of It Itself: the terrible revelation that the adults were in on it. In this way, King ties the fall-into-knowledge central to stories about the dark side of small-town Americana (per Blue Velvet: “I’m seeing something that was always hidden”) into his beloved monster-movie pulp.

Finally, we get to what the titular entity actually is: a cosmic predator from beyond spacetime, thirsting for meat flavored with fear, using glamours to project images of Itself as whatever Its victims fear most. It’s easy to mock such LSD-soaked Lovecraftian lore as overblown, and it definitely is that. But it resonates with all those other layers. Lovecraftian horror drives mortals mad, which dovetails with the trauma and repression our heroes undergo. The idea of an ancient monster that everyone knows is there but no one wants to talk about, even as it inflicts its wounds on the next generation, is an apt metaphor for all variety of social ills, many of which King addresses directly. There are multiple kinds of horror struggling for the spotlight in It, from abuse to bigotry to the Eater of Worlds variety. What makes the book interesting–if also more than a little silly–is the author’s insistence that all these kinds of horror are linked. That’s why our heroes can’t remember It: not only because the movie monster turned out to be real, but because It was far worse than the movies suggested, and It’s wearing your father’s face.

179 notes

·

View notes

Note

I absolutely love your ADWD analyses (and they're convincing me it's the best book so far), but there is just something about Jon Snow's Dance story that I seem to have doubts about. Yes, he's the closest thing to a "prophesied prince" trope we've seen in ASOIAF, but I'm not convinced of his story weight yet. Can we get a "defense of Jon Snow in ADWD"? Or are my doubts legitimate?

Thanks! I may or may not get to a series on Jon’s ADWD storyline (that’s a gigantic granite monolith of a storyline, and would take a looooong time to do properly), but I think it’s one of ASOIAF’s highlights. It’s a nigh-flawlessly constructed character arc, with every major scene and plot point furthering Jon’s internal struggle until it all erupts in that final chapter.

Indeed, despite ADWD’s reputation as being bloated and shapeless, Jon’s chapters (and he has more than anyone else in the book) have bones. It’s a rock-solid three-act affair: the first act deals with Jon finding his footing as Lord Commander, the second deals with him putting his pieces in place, and the third deals with the consequences. Jon’s central character dilemma—caught between duty and desire, the Wall and Winterfell, his brothers and his sister—is perfectly articulated throughout, neatly interwoven with every story beat. He hesitates to help Stannis, but then plunges ahead in the hopes of liberating the North from the Boltons and the Greyjoys. He’s shocked to learn Mance is alive, yet ultimately can’t stop himself from sending him after Arya. For all that the Alys-Sigorn wedding is a crucial step in Lord Commander Snow’s agenda regarding willdling assimilation, Alys was wise to appeal to him as a son of Eddard Stark. And of course, the Pink Letter brings all of this into focus: his relationship to Stannis, his mission for Mance, his love for his home and family having put his duty to the realm and his brothers in jeopardy. Terrific storytelling, top to bottom.

60 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The most basic rule of editing is that if you can’t bear to read it, no one else can either. So when you find yourself skimming, commit murder.

Marion Roach Smith (via writingdotcoffee)

4K notes

·

View notes

Note

Any thoughts on yesterday's Rick and Morty (btw, thank you for introducing me to the series)?

You’re welcome! And, hooey, where do you even begin with the level Rick and Morty is operating on at this point? From superhero parodies to gore-speckled pickle fights, they’re regularly conjuring up entire space operas’ worth of solid gold material only to deconstruct it utterly with savage glee by episode’s end, again and again. They’ll start with a reasonably amusing premise, deconstruct it a quarter way through, reveal a much bigger plot halfway through, pause at the three-quarters mark to laugh at the first plot, before burning it all the hell down at the end in a fit of philosophical inquietude and drunk flailing. In other words, the show is structured like Rick’s thought process, and is all the better for it.

“The Ricklantis Mixup” bolsters my overall take on the show–it’s about the corruption of Morty and his gradual supplanting of his grandfather. The Citadel had previously just been a goofy backdrop, an excuse to have dozens of Ricks and Mortys in one place. This episode, however, thoroughly explores it as a Verhoevian dystopia, via four different stories and four different genres, over the course of only 22 minutes. You could easily imagine a 90-minute feature built out of this, but they cut absolutely everything they didn’t need. Structurally, it’s sublime.

The Verhoeven influence is most prominent in the framing of media, both tongue-in-cheek (the Rick reporters are kept in a strict hierarchy of attractiveness) and utterly horrifying (an ad showing “Simple Rick” trapped in a mental loop of watching his daughter say she loves him, so his emotion can be used to flavor candy). This is a world of Rick not as a flaky anarchist, but as a dedicated tyrant. He exploits his own kind, until one factory worker Rick snaps, kills his boss Rick and Simple Rick, and demands his freedom, roaring that they’ve just recreated everything they hated about humanity. And then…Ricky Wonka shows up to make his dreams come true, because of course he does, and just when you’re giggling, he shoots our hero in the back and has him replace Simple Rick, forever in a loop of his delusion of escape.

There is no way out, and the Mortys know it better than anyone. Their “Stand by Me” riff ends not with them finding a dead body, but creating one, as the protagonist chooses what they all know is suicide over the meaningless life of an asshole’s sidekick.

So how do the Mortys escape? One seems to have the answer, arguing that Rick’s recklessness and roguishness have doomed their society, and in particular, the fortunes of Mortys. It sweeps him into office…but his Campaign Manager Morty realizes at the last second that the new President is the Evil Morty from “Close Rick-counters of the Rick Kind.” His assassination attempt fails, and he’s shot out into space.

For those keeping track, of our four protagonists, that’s two dead and one arguably in a fate worse than death. The only one to make it out in one piece is Cop Rick, and this storyline is the heart of the episode. His partner Cop Morty is your classic worn-down cynical aggressive rulebreaker cop, hateful and murderous to his own kind, and his worldview is in large part a product of a world in which Ricks who are either careless figureheads or detached monsters have been running things. Again, the core of the show is how Rick has affected Morty, and so here we have a naive Rick being unloaded upon by a cynical Morty, the latter viciously mocking Morty’s role (“I want to go to school and play with balls and masturbate!”) before shooting one of his own. Cop Rick shoots him in return. I can’t help but think of Rick having to shut down Morty’s rage during the Purge, or Morty’s growing addiction to Armthony, or his sincere attempt to murder Rick in the Season 3 premiere…

Ultimately, all four storylines are meant to reflect aspects of these two characters, and in the end, Rick has been toppled, humbled, and trapped in his own delusions. Morty, meanwhile, has shed the last part of him that cares, and rules with an iron fist; Cop Rick is one of his stormtroopers now. And he has only begun to fight. The show has its antagonist.

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

Art forgery is the best crime tbh. It requires absolutely incredible artistic talent, technical skill, and attention to detail to make convincing fakes. Does anyone get hurt from it? No! The only people who suffer for it are the extremely wealthy who want the prestige of having original paintings in their own homes. It’s full of international intrigue and mystery. Perfect.

323K notes

·

View notes

Text

Honestly noah fence or disrespect or anything but why do people care about Elia so much on this site?? Her main purpose in the book is to be a sad character and that’s literally it. I don’t even get why people are upset about the annulment cause we all know D&D don’t understand or care about the source material and this would never happen in asoiaf. But honestly theres a strange amount of stans for this specific character with almost no real purpose in plot.

2K notes

·

View notes

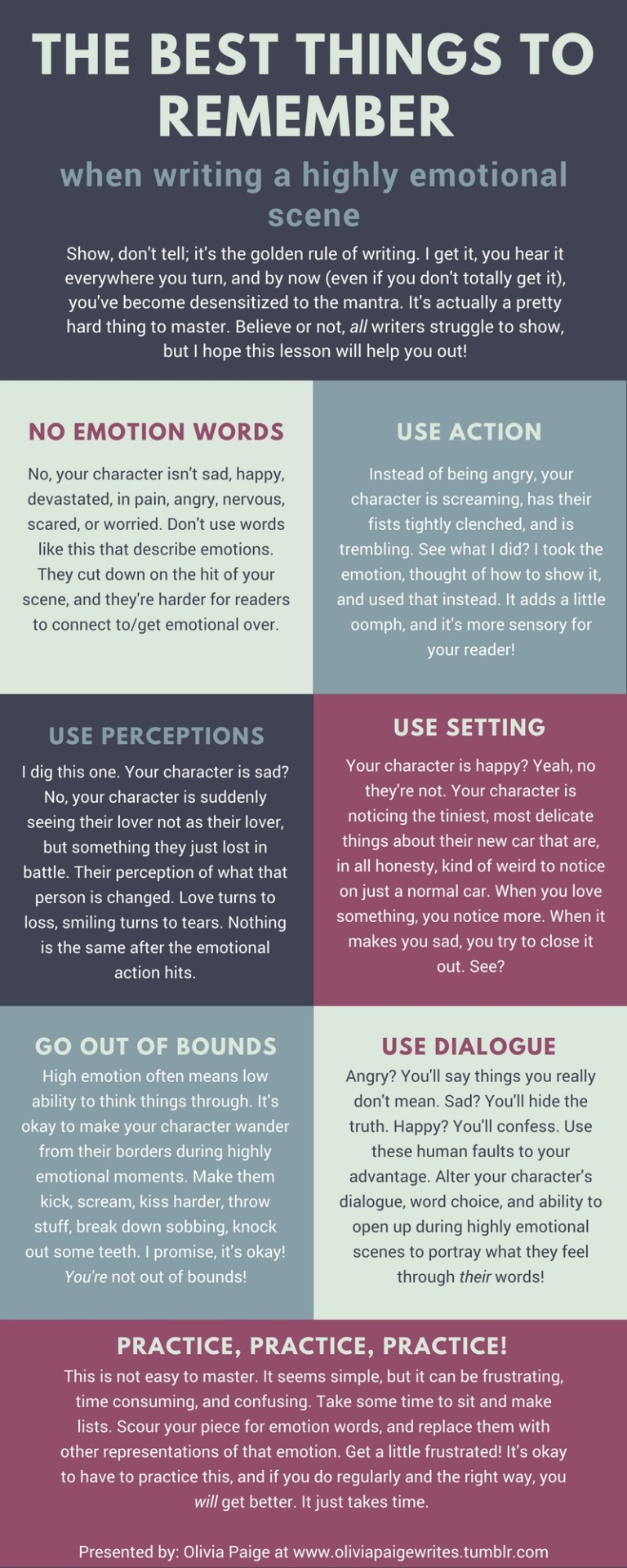

Photo

Brill

THIS IS AN IMPORTANT ONE! Don’t ignore this in your writing!

108K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey PQ! I was wondering what your thoughts were on the new Rick and Morty episode? Cheers for the great prose!

Thanks! I wrote a li’l thread about it. Basically, along with the delightful Mad Max shenanigans and Rick doing his usual Drunk Marwyn schtick, the episode advanced the underlying story of the series: Morty gradually giving into his dark side and becoming like Rick…or worse.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dark beast by snaku6763 (Markus Härma)

235 notes

·

View notes

Note

How would you fix up the prequels in Star Wars? Especially with regards to exploring Anakin's transformation/arc, given that Anakin goes from preventing the (immediately required) execution of Palpatine to killing lots and lots of innocent Jedi children/warriors in about 10 minutes of screen time and a few(?) hours of in-universe time. Thanks

*cracks knuckles* Tagging @the-winged-wolf-bran-stark in this, as we’ve talked about it before.

Big important change right off the top: let the actors improvise, experiment, and riff off each other with their dialogue, as often happened in the original movies. George Lucas is great (nigh-peerless, actually) with concepts and storyboards, but he himself has admitted he’s not great at dialogue, especially romantic dialogue. This was the #1 problem with the prequels, and I think the interesting, surprisingly risky stuff about this trilogy would’ve gotten more attention if the mediocre-to-awful dialogue wasn’t slapping everyone in the face every few seconds.

After that? For me, the #2 problem was how many intriguing ideas and characters didn’t get fleshed out while Lucas lavished time on stuff he didn’t need or just wasn’t working. For example, while the Gungans did allow Georgie to give us some lovely visuals…

…that alone doesn’t justify their existence. They’re tiresome and super racist in conception, as are the Nemoidians. In terms of non-humanoids to lavish more time on, go with Kamino, as that was easily my favorite part of AOTC.

That also leaves the primary antagonist role—and a lot of screen time—open in TPM. Use that narrative space to beef up Darth Maul’s role significantly and move up by a movie the introduction of the Separatist movement and Count Dooku (while changing that embarrassing name; low-hanging fruit, I know, but that doesn’t make it any less true). Position Maul as a mercenary working for the Count, while hinting that he’s really Sidious’ mole inside the separatists; start the PT with Maul kicking off the Separatist movement by attacking the Republic and the Jedi in some instantly memorable fashion, rather than something something trade dispute. Keep the whole “faction rebels against the Republic which is too schlerotic to respond properly” plot framework of TPM, but give the antagonists some real heft. Use their rebellion as a way to interrogate and investigate the failings of the Jedi and the Republic. Because that was, by far, the best idea in the prequels: the Jedi and the Republic didn’t just lose, they failed. Neither of them could handle the challenge Palpatine posed.

This would also give the Separatist movement a distinct ideological tenor and dramatic reason for being other than just “swarm of droids and/or idiots to be manipulated by Palpatine.” The Count needs to genuinely believe that he’s doing the right thing, taking on the corrupt and shiftless powers that be both in the Republic and on the Jedi Council, with no idea that he’s being manipulated by the Sith. Indeed, build up the Count throughout that first movie as a dark mirror of Qui-Gon. That’ll make it more meaningful when Obi-Wan and the Count cross paths in AOTC–and you need to spend a lot more time on that dynamic. Cut half the Battle of Geonosis to make room.

Thus, when the Separatist movement is finally destroyed in ROTS, it’ll carry some weight: they saw the problems, but put their faith in the wrong people. And that, of course, dovetails perfectly with Anakin’s own story. To your question in that regard: his turn to the dark side needs to be seeded into his overall worldview instead of just his knee-jerk emotional reactions. There’s a little of that in AOTC (“then they should be made to”) but not nearly enough. Spend a lot of time on Anakin arguing with Senators and Jedi Masters about their approach to the war, politics, and life in general. Have him develop theories about politics and the Force that have a gut appeal compared to the older and not-actually-wiser heads around him while still being worryingly close to Fascism In Space. Stick with the original concept of Padme founding the Rebellion, and have this political schism be the cause of their relationship falling apart. She too is frustrated with the Council and the current leadership of the Republic, but is horrified and walks away from him when she learns he sided with Palpatine. Anakin hesitates for a moment, but then hardens his heart and turns on the younglings; Vader is born.

170 notes

·

View notes

Note

Regarding Snyder's attempts to make Superman human, I think he should have borrowed from MCU wrt a similar character: Captain America. MCU makes him relatable by keeping an eye on, not Captain America, but Steve Rogers. Snyder should have kept the focus on Clark Kent to make him more relatable rather than his alter ego. Your thoughts?

Agreed. Where Man of Steel really started to go wrong is how it handled Clark’s childhood in Kansas. The prologue on Krypton is easily the best part of the movie; it certainly has issues with storytelling (the codex is a completely unnecessary MacGuffin) and tone (“I WILL FIND HIM!”) but the basic dynamic between Zod and Jor-El, and how it relates to the larger issues at play, comes through clearly and effectively. Similarly, Batman v Superman solidly establishes Batman’s place in this universe early on with a creative perspective-changeup on MoS’ climax. Both movies really go off the rails when the actual plot starts.

In MoS’ case, handling Clark’s childhood via flashbacks fatally sabotages the movie on several levels. First of all, as Dan Olson noted, the flashbacks don’t actually intersect with Clark’s adult story in any meaningful fashion. The past and present don’t inform each other; there’s no thematic buildup or narrative propulsion, just a series of scenes floating in the narrative ether. Secondly, giving us so little time in Smallville makes it hard to get invested when Snyder starts blowing it up. It really comes off like Clark Kent’s Kansas doesn’t mean anything more to the writer and director than an excuse to indulge in Malickian texture; the punch-to-the-face product placement in that fight doesn’t help either, because given that lack of investment, it ends up feeling like what Supes is defending from Zod’s wrecking crew isn’t his neighbors, but U-Haul and Ihop.

Most importantly, though, and relevant to your question: both that structural approach to the Kansas portion of Clark’s story and the actual content of that portion makes it very difficult to connect to him as a character. The values he was raised with in MoS, unlike in other media, consist of “don’t help people because they won’t understand you and anyway you don’t have any obligation to use your powers to help people.” This is what you get when you put an Ayn Rand fan in charge of an altruist’s story. Moreover, Clark doesn’t ever really push back against this frankly terrible lesson. We’re never shown why he cares about saving humanity. We’re never shown how he feels about Pa Kent’s values, or indeed Jor-El’s. We’re never given a clear coherent sense of who Clark Kent is, what he wants, what he needs, how these wants and needs are in conflict. He’s just a sad-faced mute stumbling through a story that’s really more about his father figures than him.

And yes, First Avenger is an appropriate contrast, because that movie makes it crystal clear who Steve Rogers is.

So when MCU Steve throws himself on a grenade, it’s meaningful, because we know who he is and why he’s doing it. When DCEU Clark sacrifices himself to stop Doomsday, it’s not meaningful, because we never got a strong dramatic sense of who he is and why he’s doing it.

73 notes

·

View notes