Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

2022 Favorites

Rankings being arbitrary and all, there's still zero hesitation for this year's top gun.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

1 note

·

View note

Text

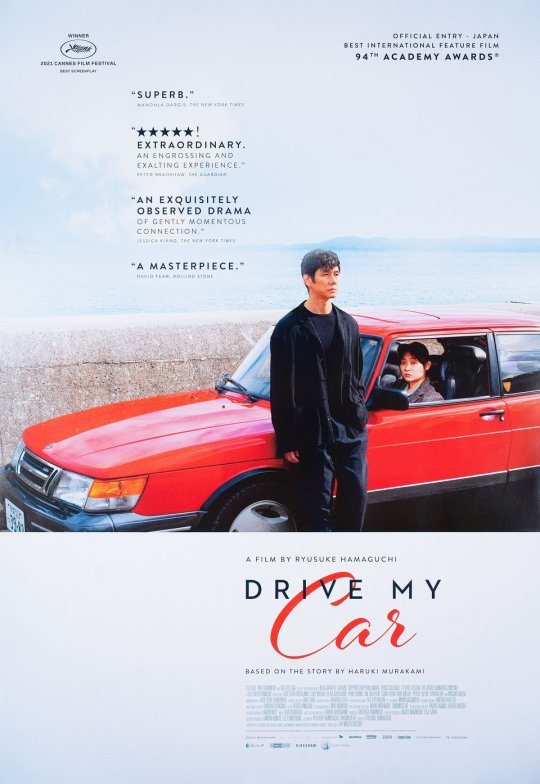

Top Films of 2021

11

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

1 note

·

View note

Text

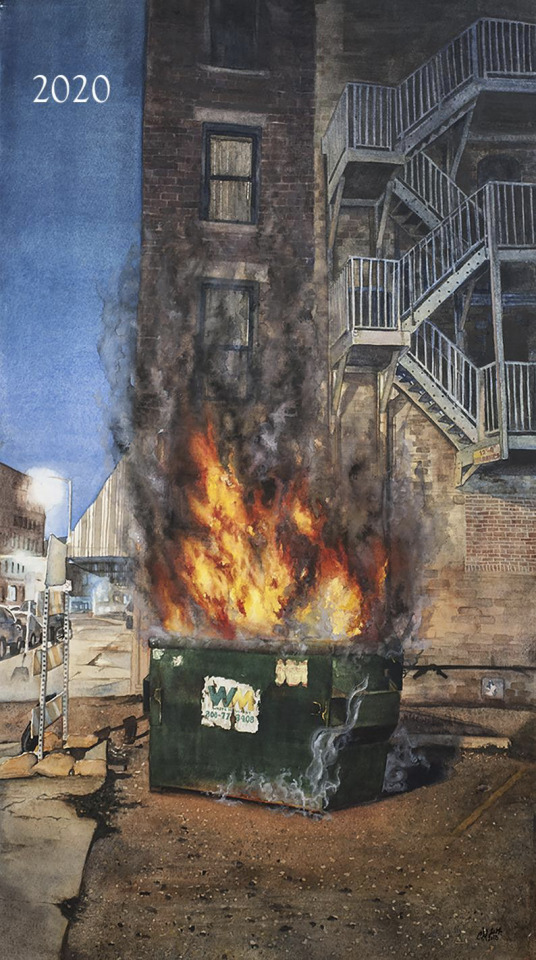

The Most Affecting Films of This Past “Year”

While gazing into the abyss of 2020, I don’t know if that hellmouth gazed back into me as Nietzsche envisioned it, because, like many, I fought this year’s monster in my sweats and talking to the walls while I scraped the barrel of Netflix for SOMETHING NEW to watch.

But I damn sure threw out any organizing rules for what qualifies as a “film.”

When called a “limited series,” long-form storytelling becomes cinema. And there shall be no argument. Thanks to The Queen’s Gambit and company, a number of these “films” by any-other-name delivered and found their way here.

Plus, it’s now a good stretch into 2021 and the very-arbitrary rules of our Time Before the Coronapocene are being met with a weary “Fuck it.”

Then there’s the possibility, as you discover when screening Arrival, that time doesn’t work the way we think it does...

“People like us who believe in physics know that the distinction between past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.”

- Albert Einstein

HONORABLE MENTIONS

The Explicitly Genre, the Dark-Hearted, & the B Movies

The Other Ones

Doctor Sleep Director’s Cut*

(*released in 2020)

The Godfather Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone*

(*yes, this was technically released 30 years ago but Coppola’s new cut works like a new film)

IT GOES TO ELEVEN

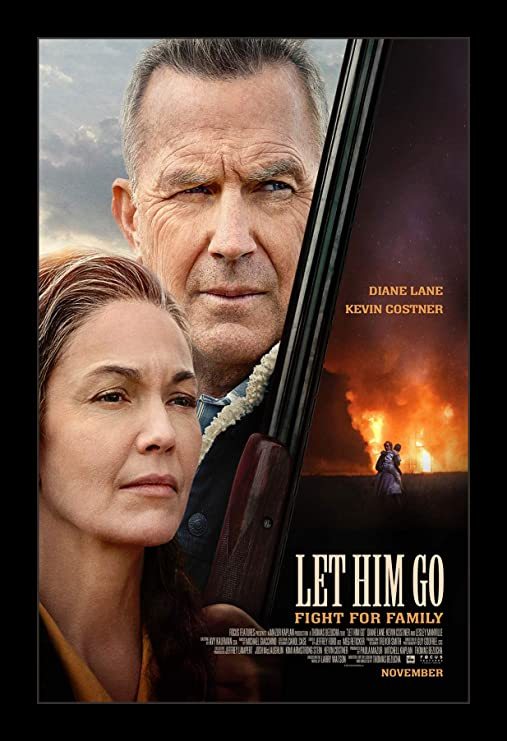

11. Let Him Go

Give me Costner and Lane in a neo-western all day. This is best viewed without knowing anything prior and far more somber than expected.

Loved the gender role-reversal as Lane dons the ten-gallon attitude typically worn by a male character.

10. Promising Young Woman

Sadly spot-on in its enraged message. Dark, dark, dark, dark, dark comedy(?).

And not for everyone.

But if you’re game, then this furious blast of filmmaking will be appreciated. Notice the foreshadowed symbolism spattered in neon and pink throughout (Saint Cassandra?) and the ending works. Mulligan being transcendent as always here.

9. Porno

Mileage will vary depending on one’s tolerance for/appreciation of severed male genitalia jokes. Being 14 years old at heart, I laughed myself hoarse.

A throwback with intelligent subtext about fundamentalist religious norms of repression and the dangers of a sex-negative culture.

8. Taylor Swift - Folklore: The Long Pond Studio Sessions

The album = classic already.

The documentary = downright magical.

7. Bad Boys For Life

As an old guy who also has some gray in the beard, I love how far they lean confidently into the old guy-ness. Been riding with these bad boys for 25 years now.

Just take my money already for the next installment.

6. The Queen’s Gambit

Cinema-as-a-novel. Sports movie as character study. Evidence that when you give a writer movie-budget money and trust their vision, you can get a hit. And a last episode that brings ALL THE JOY!

Bravo, Netflix.

5. The Outsider*

(*cancelled after one season so I’m calling it a “limited-series” and thus a film)

Just the weird and dark adaptation of King that fits with HBO and excises what I assume to be elements that work better on the page.

Its tone haunts and elliptical editing rewards patience, and Cynthia Erivo should be in everything.

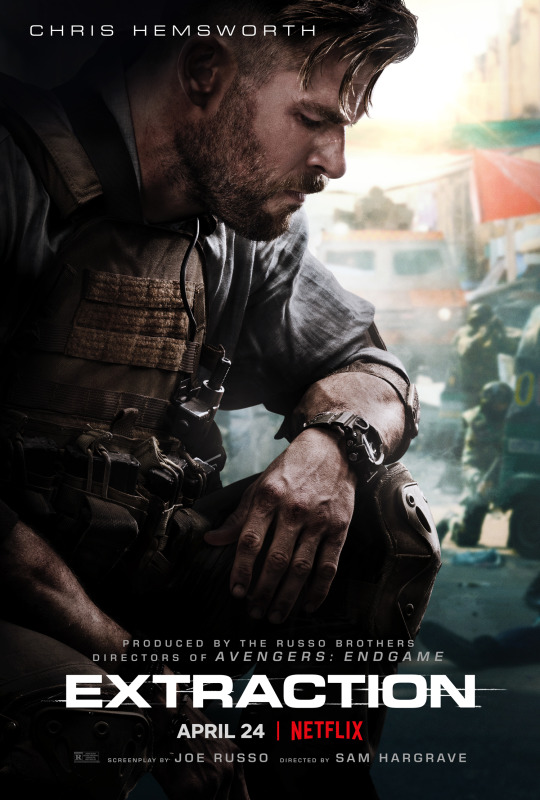

4. Extraction

As subtle as having a lead character named Tyler Rake kill a dude with a rake -- which definitely happens here. On paper, its armature of a suicidal gunslinger with a weary soul seeking redemption in John Wick’s stylistic shadow shouldn’t work.

But grit and kinetic craft and heart tugging father and son parallels and an impressive look at what constitutes masculine “courage” and what masquerades as it under the guise of violence give zero shits about “shouldn’t.”

3. Tenet

“Don’t try to understand it. Feel it.”

“.ti leeF .ti dnatsrednu ot yrt t’noD”

A friendship love story at its core that’s going to live as an artifact and defy time, which is appropriate.

Branagh cooks the world’s largest ham and does so brilliantly.

So fun if you don’t try to play chess with Nolan (you’ll lose) and simply let it rip into the space-time continuum.

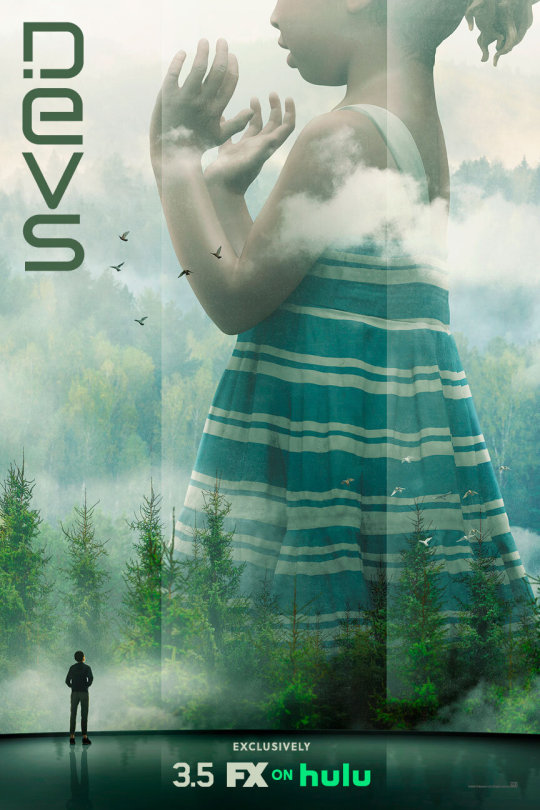

2. Devs

It took three episodes (read: chapters) for this to wrap me in its embrace but, holy multiverse, did it ever. A noodle baker of the highest craft, Alex Garland shows again that whatever he touches is going to be a favorite.

There’s multiple references to great poetry, a diverse cast reflective of humanity, and that many worlds theory to invite many more viewings.

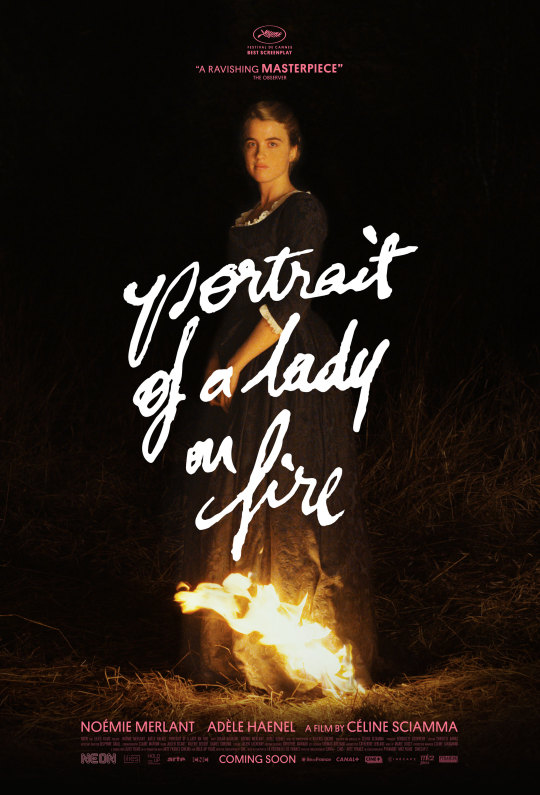

1. Portrait of a Lady on Fire

Gobsmacked, I kept telling myself there’s no way the next scene or sequence could top the previous...

Then the bonfire singing happened...

Then an Orpheus and Eurydice allusion reversal...

Then the opera scene and me having an out of body experience for almost five hours after the credits slid up the screen.

Céline Sciamma’s film is the equivalent of Michael Jordan in an 80’s dunk contest: despite an abundance of competing talent, it can’t even be called a “contest.”

Art shouldn’t be ranked anyway, but Sciamma and everyone involved are all, like…

1 note

·

View note

Text

Favorite Films of 2019

These picks are not original or provocative. Toss a hundred film nerd and film critic “year’s best” lists into a blender and it’ll look like mine.

Yet, putting this together, a few thematic connections became clear:

How regret braids itself to loss, in some cases the latter being a gateway to positive growth and renewal, in others just leaving you afraid of the dark against the knowledge that we all die alone (looking at you, Irishman). The cost of economic inequality and evils of expected privilege also put blood in the veins of at least three titles here. And there’s always promise in how genre films can work allegorically -- especially with horror.

As a cinematic year that delighted both senses and intellect, this one buttoned the decade in stellar fashion.

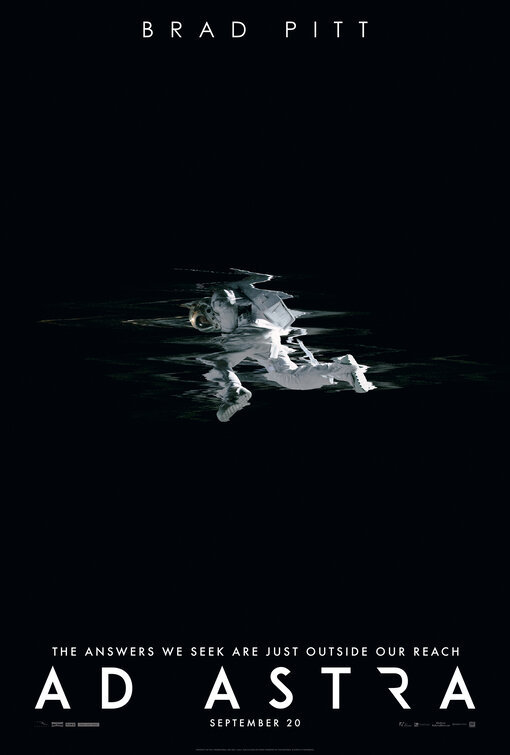

10.

While other movies on this list are subtle in exploring their themes, if you can take the overt wrestling with ideas (see: the voiceover) about men isolating from their emotions, inherited parental demons, and depression, then you might find the last fifteen minutes as sublime as I do.

It’s been dubbed “Apocalypse Now in space,” yet this heart of darkness melts into a surprisingly humanist and hopeful coda.

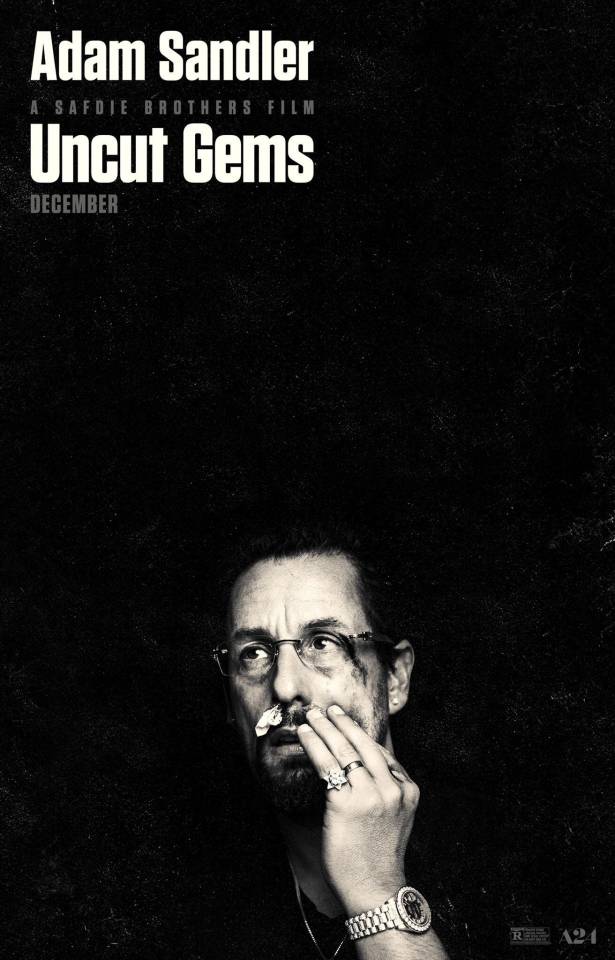

9.

Ever had a panic attack while juggling flaming chainsaws in the bed of a truck as it busts through the guard rail to plunge 500 feet from a bridge into an icy river on the very night you decided to try meth by injecting it into your femoral artery?

Neither have I...

but that scenario must be akin to the visceral, adrenaline/panic blast of a sensory experience that only cinema can provide and sure-as-Sandler does in this parable of folly and compulsion.

8.

Who would’ve thought a paperback inspired murder mystery could offer one of the more incisive commentaries on greed and wealthy white privilege of 2019?

(See this for dessert after the double feature of #4 and #1.)

7.

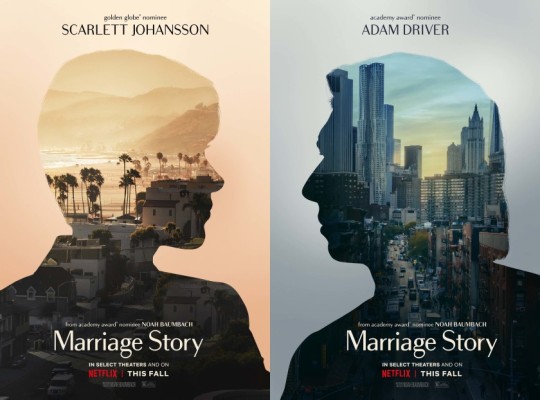

Bruising yet hopeful. It’s an exercise in balancing POV and resolves in perhaps the most heart-achingly beautiful reading of a letter I’ve ever wept to from the couch.

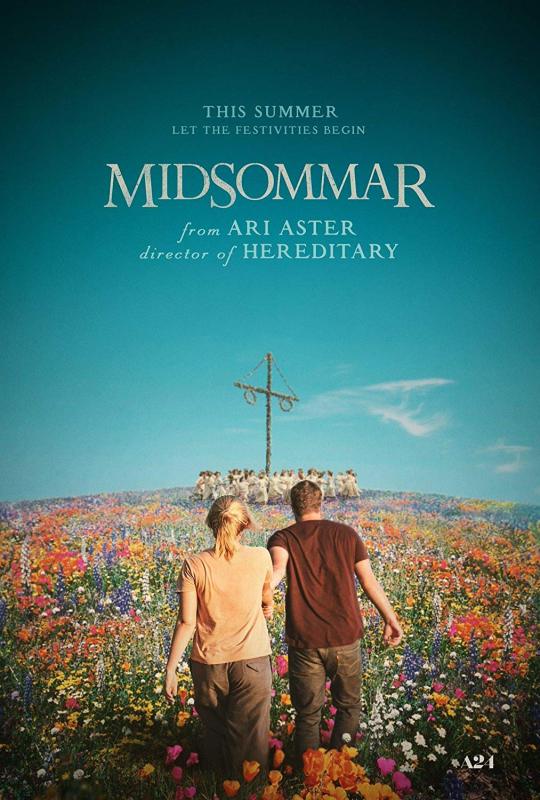

6.

Like the other horror title here, you can read it in multivariate ways -- particularly as a strange trip through grief and an escape from a toxic relationship. Or you can just admire the craft that’s as radiant as the Scandinavian summer sun in Aster’s sophomore feature.

5.

Depending on both randomness and the choices we make, life may or may not conclude in despairing loneliness. Scorsese’s least sexy gangster film is one that substitutes the cocaine high of that lifestyle with the oft-bleak spiritual consideration of mortality in his religious oriented films.

The last 45 minutes are god level and that frame-within-a-frame final shot is devastating (but in the best kind of way).

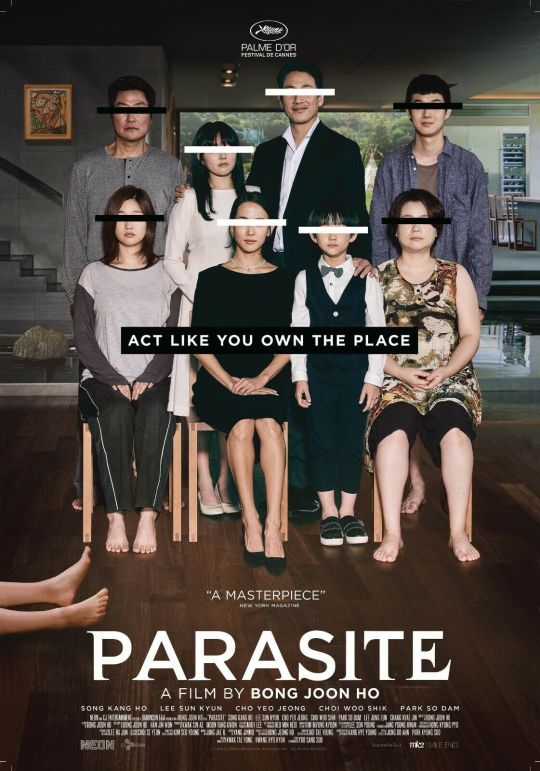

4.

Such a twisty, brilliant story on its own and so technically supreme that every shot is perfect yet unobtrusive, this can also be read as an indictment of social and economic imbalance. (Pair it in a double feature with #1.)

As director Bong Joon Ho has said, "We all live in the same country now: that of capitalism."

3.

A nostalgia + regret cocktail that provokes but will endure with time and is my pick for most likely to elevate upon rewatch ten years down Cielo Drive.

2.

Lovely. And melancholy. And so fucking well made.

Greta Gerwig has dropped the best-young-director-in-American-cinema mic.

1.

A masterful use of cinematic language in a horror-thriller that accomplishes both, Peele’s second movie also delivers the year’s finest acting performance (Lupita and Lupita!). You can take Us on its surface and it still kicks the ass of every other genre picture not on this list up and down the block.

Yet, for me, the fun is in the dozen ways it can be interpreted.

My favorite: a gut-punch reminder that we shouldn’t be pointing at others in some tribalism-as-blame-deflection for the world’s ills but instead all commence to looking at ourselves searchingly in the mirror.

Because in order for each of us lucky enough to have Netflix and Costco and iPhones to continue to posses them, someone, and in fact a great many people, remain beneath us getting stepped on.

Here’s to 2019 at the movies:

“I got five on it.”

0 notes

Text

Best Films of the Decade: 2010 - 2019

(A terribly subjective and arbitrary prisoner-of-the-moment list.)

Honorable Mentions

The MOST Award

Deserves to be in a category by itself.

Top Twenty

20.

19.

18.

17.

16.

15.

14.

13.

12.

11.

10.

9.

8.

7.

6.

5.

T- 4. (Hardy Driving I)

T- 4. (Hardy Driving II)

3.

2.

1.

0 notes

Text

Favorite Films of 2018

I didn’t see all the titles from 2018 on my wish list but that will be remedied over winter’s duration. What follows are my Honorable Mentions and a completely arbitrary ranking (nowhere more evident than looking back on the previous three years and seeing how my appraisal of those films has changed) of my Favorite Films of 2018, a terrific twelve months in cinema.

May these titles inspire you to continue to stretch your viewing choices.

- Matt

Honorable Mentions

Favorite Films

15.

14.

13.

12.

11.

10.

9. - Tie

8.

7.

6.

5.

4.

3.

2.

1.

0 notes

Text

The Most Affecting Films of 2017

I love putting this list together because a.) I’m a film geek and own it, b.) this writing exercise is cheaper than therapy, and c.) it helps me discover previously unrecognized themes shared across my selections. The thread of history runs through these picks, that of nations as well as the complex and messy relationships between parents and children. History is parent to our present, and thus the thematic through line of my favorite movies of 2017. Each title brought me to tears or rented space in my mind for days after the initial viewing, often both, but earned this response through quality of storytelling.

Choosing my top ten was difficult (see the following “Runners Up List” for evidence) because 2017 was a fine year in film. We should celebrate cinema, and the opportunity to do so, as long as it remains this dynamic.

-Matt

Honorable Mention: Their Finest

Directed by Lone Scherfig

Written by Gaby Chappe and Lissa Evans

A movie celebrating storytelling and writing, chronicling the making of a movie about the Dunkirk rescue, set in England during the Blitz, addressing the role women played in the war effort, packed with an embarrassment of Britain’s best character actors, exploring how cinema’s escape can help heal us in times of crisis, and that is also a love story has no right to work. Scherfig’s film defies such limitations and hops between these aspects like a trapeze artist. It’s a crowd-pleaser, a heartbreaker, and a movie celebrating movies, all buoyed by Gemma Arterton in the lead.

10. The Lost City of Z

Written and Directed by James Gray

Cinematography by Darius Khondji

The real Percy Fawcett’s 1925 disappearance in the Brazilian jungle provides an unanswerable question that hangs over Gray’s film as he endeavors to explore mysteries of the egocentric self through immersion in the natural world. Like the protagonist, this seems simultaneously paradoxical and fitting.

Some clever non-linear editing and a final shot of Nina Fawcett, the only actual hero here, walking into the reflected image of a jungle, make for a lingering metaphor on those understandings our hearts are granted, and those we can never attain.

9. Toni Erdmann*

Written and Directed by Maren Arden

When I thought this dark European comedy couldn’t get more surreal or funny, it didn’t, but instead ends with a peerless final beat, then drops The Cure’s “Plainsong” over the credits.

Cut to me radiant with joy at what cinema makes possible.

Hollywood stories of parents and children aren’t ever this delightfully weird, or dappled with scenes that let us find our own insights about economic disparity, sexism, and capitalism’s darker outcomes. Hollywood stories aren’t ever this genuine.

Maren Arden proves herself a visionary, not just among up-and-coming female directors, but all directors, and since her open-ended final scene is perfection, I’ll let the last dialogue in her script finish the same way:

The problem is, [life is] so often about getting things done. And then you still have to do this, or that. And, in the meantime, life just passes by. But how are we supposed to hang on to moments?

* released in 2016 but I had no way to see it until 2017

8. The Big Sick

Directed by Michael Showalter

Written by Emily V. Gordon & Kumail Nanjiani

Gordon and Nanjiani’s story (based on the origin of their own marriage) took me two viewings across two seasons to relent and finally love it. Now it has my whole heart thanks to an earned emotional response and a script respecting the perspectives of all its characters. Likely the best screenplay of the year that might not be recognized as such, stand up comedy and parents are rarely revealed onscreen with such nuance, and never before in the same film.

7. Five Came Back

Written by Mark Harris (based on his book Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War)

Directed by Laurent Bouzereau

This three-part Netflix documentary chronicles the contributions from five of the top directors in Hollywood during WWII, many of whom gave up lucrative careers to serve the war effort via their craft. We see how filmmaking and storytelling, as the translation of fact and occurrence through moving image, can be a weapon and should be used with care. The stories of these five directors and how their lives and art were impacted by the conflict is engagingly humane. And the talking heads (aka legendary current filmmakers) are so damn insightful. MVP being Guillermo Del Toro.

We celebrate such humanity, and in it our own, flawed and beautiful as both might be. This is best captured in Capra’s final voiceover proposing hope where it is needed.

6. Wind River

Written and Directed by Taylor Sheridan

Sheridan’s crime-as-myth story is most concerned with grief and the ways we numb ourselves to pain at the cost of the memories of loved ones lost. Winter and the West stand in a neo-western backdrop where he colors the idea of how struggle can hollow out even the strongest among us.

We get our genre kicks in the Mexican Standoff shootout (praise to the screenplay-rulebook shredding use of editing and a flashback to set up this reckoning). The patience in ending his film with not one but two conversation scenes shows a preference for empathy over spectacle, and the way the injured souls connect therein haunts me.

5. Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri

Written and Directed by Martin McDonagh

I enjoy being challenged by a film. McDonagh’s picture beat the shit out of me then tossed me a lollipop, and I beamed like a lovestruck idiot. An early reference to “A Good Man is Hard to Find” alludes that that there will be no predominant tone to cling to but instead a vacillation of many throughout this winding trip into darkness where any good that exists is a miracle. In the final scene and sublime character change of Sam Rockwell’s Officer Dixon, it does.

4. Blade Runner 2049

Directed by Denis Villeneuve

Cinematography by Roger Deakins

There wasn’t a more thoughtful film this year than Deakins’ visual magnum opus. The intelligence expected of Villeneuve surfaces throughout in beautifully complex questions about life, witnessing, and how we achieve our sense of identity.

The choice of Gosling’s K / Joe as protagonist, his illusory sense of importance as the “one” and what is done with this concept, shows how important it is to value the willingness to make choices, even when they seem tiny and tossed into the void. In Joi, he may have found a facsimile of love, or he may have actually found it. In response, we question our right to declare another’s life or love “artificial”. The Hero’s Journey archetype is so common that it’s almost instinctive. Villeneuve subverts these expectations by stripping heroic action to its purest and leaving us with K / Joe’s not-tears in the ashen snow.

The acting is typically strong because, while he isn’t noticed for it, Villeneuve always gets strong work from his actors. Through one of Harrison Ford’s best performances, the theme of parents, children, and sacrifices made just for the latter’s prospect of a better life is most poignantly rendered in one line: “Sometimes to love someone, you got to be a stranger.” As 2017’s best sympathetic villain, Luv doesn’t possess the freedom of her inferior replicants; she is bound to Wallace, a slave in her programming. Wanting to be special, to be the “best one”. This denied want and inability to make her own choices, to create life and be alive, warp her into a destructive force seeking to stomp out anything that reminds her of her chains. Leto’s megalomaniac Wallace is a god-aspiring big bad in the Greek chorus role, showing up to voice the film’s themes but in a way that avoids ponderousness.

I could write an essay on this film. (Note to self: write more essays on films.)

3. Lady Bird

Written and Directed by Greta Gerwig

Gerwig’s work is so accomplished that my mind boggles when contextualizing it as her first directed film. The movie world exists here as specific enough to leap outside of time and place in that mysterious dynamic of singular-becoming-universal. Coming of age stories with comedy draped around them, or them around it, are usually judgemental of broad supporting characters who get portrayed in one shade only. This film is so balanced and sympathetic to its people, and I say “people” with intention, that we turn from cursing them to pitying to loving as fluidly as we do from laughing to choking up. The final sequence might be the year’s most affecting editing through a use of different characters in essentially the same shot, and shows that car chases have nothing on cross-cutting between drivers in the Sacramento magic hour.

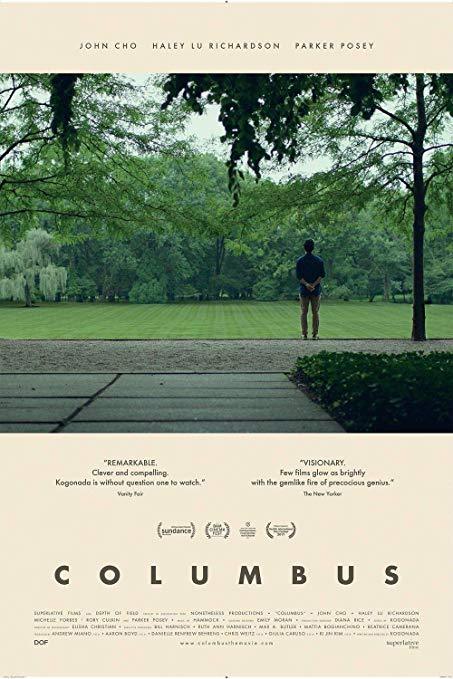

2. Columbus

Written and Directed by Kogonada

Sheila O’Malley in her Rogerebert.com review:

"Columbus" is a movie about the experience of looking, the interior space that opens up when you devote yourself to looking at something, receptive to the messages it might have for you. Movies (the best ones anyway) are the same way. Looking at something in a concentrated way requires a mind-shift. Sometimes it takes time for the work to even reach you, since there's so much mental ballast in the way. The best directors point to things, saying, in essence: "Look." I haven't been able to get "Columbus" out of my mind.

Wholeheartedly agreed. It clung to me. First time director Kogonada gives us an immaculate use of the frame and mise en scene. My eyes wanted desperately to eat the screen, each and every frame a morsel. And my entire being wanted to remain in the film’s world. Sadness and all.

Kogonada’s work isn’t all visual gloss but uses stillness and subdued conversations to belie an emotional tempest inside each of the two characters. This is a romance, but one just as in thrall with life as it is with clean modernist lines and the creation of form through negative space that here symbolizes those unknowable aspects of Jin and Casey (Haley Lu Richardson lights the screen in my favorite performance this year), and by extension those they love. We carry our parents with us just as these buildings carry their histories. Columbus’ characters need to navigate the empty spaces in and around themselves to connect, even if fleetingly.

1. Dunkirk

Written and Directed by Christopher Nolan

Cinematography by Hoyte Van Hoytema

Score by Hans Zimmer

I can rightfully be called a Christopher Nolan fanboy, but there’s no arguing the viscerality of this experiment. Nolan, Hoyte Van Hoytema, Hans Zimmer, and the rest of their collaborators crafted a singular war film that really isn’t a war film. It’s a story more existential. Time is elided, shattered, and edited with an exactitude that comments on history unlike any other movie in this genre.

That audiences responded to a story asking them to participate, emotionally and physically, but learn little of its characters is also fitting for the theme of people choosing to risk their own well being for the betterment of others. The lesson is to put aside your wants and let an experience take you.

The propulsive score, like the tension, never relents. How such induced anxiety can be thrilling is for later study (and this film will be studied for decades hence). It’s the notion, however, that I can be brought to tears by the shot of a Spitfire coasting across sky, out of gas but not fight, by small boats dotting the sea that are referred to as “Home”, and by Mark Rylance simply nodding to his son in acknowledgement that the right thing to do is often an act of empathy running against our in-the-moment emotional surge, that belies an elegance words can represent, but only sound and image can actually invite you to feel.

_______________________________________________________________________

We are born into a box of space and time. We are who and when and what we are and we're going to be that person until we die. But if we remain only that person, we will never grow and we will never change and things will never get better.

Movies are the most powerful empathy machine in all the arts. When I go to a great movie I can live somebody else's life for a while. I can walk in somebody else's shoes. I can see what it feels like to be a member of a different gender, a different race, a different economic class, to live in a different time, to have a different belief.

This is a freeing influence on me. It gives me a broader mind. It helps me to join my family of men and women on this planet. It helps me to identify with them, so I'm not just stuck being myself, day after day.

The great movies enlarge us, they civilize us, they make us more decent people.

-Roger Ebert

_______________________________________________________________________

Promising 2017 releases that I haven’t seen yet and might vie for retroactive inclusion on either this or the “Runners Up” list:

Star Wars: The Last Jedi

The Disaster Artist

Darkest Hour

Mudbound

First They Killed My Father

Spielberg

The Post

Molly’s Game

Phantom Thread

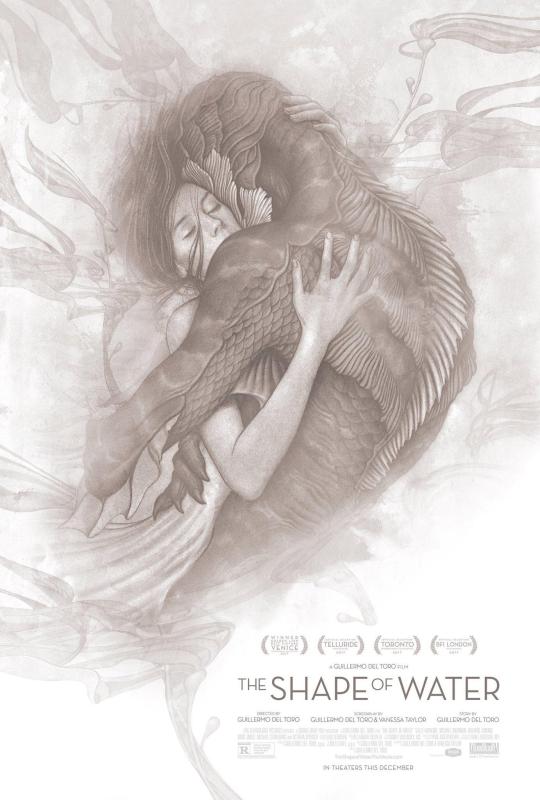

The Shape of Water

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Best Films of 2017: Matt’s Runners Up List

John Wick Chapter 2

Logan

The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected)

Walking Out

1 note

·

View note

Text

2017 Essay: Sarah Ekkelboom

Never Surrender

“We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and the oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air. We shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be…”

War is a horrific thing. It devours the lives of young men, the bounty of the land, and the recourses of nations, while giving nothing in return. War has a way of bringing the darkest parts of humanity to the surface, revealing the ugliness of man. Man, however, can be unpredictable. War can also reveal the good in people, showing noble characters who take a stand against the ugliness around them. Christopher Nolan’s 2017 war movie, Dunkirk, shows the horrendous aspects of war, alongside the noble actions of individuals. This extraordinary film takes the battle of Dunkirk and, like Churchill mentions in his speech, looks at it from the beaches, the landing grounds, and the air, showing people who took a stand against tyranny. This film reveals the hope in what seemed a hopeless situation, proving that goodness lives even in the face of warfare.

Dunkirk begins with our protagonist, Tommy, walking through the streets of France, when gunshots break out and kill the three men who were with Tommy. This violent beginning sets the tone for the rest of the film, once the action begins it does not let up. Much like war itself, there is little rest, and no safety. The audience is immediately submerged in the battle alongside the characters, we can almost feel the fear, the desperate fight to survive, and the hopelessness of being trapped within sight of home. The sound track adds to the tension, allowing us to feel the unrelenting suspense along with our characters. Our land protagonist, Tommy, catches a man stealing a fallen comrades uniform. Instead of reporting him, Tommy lets it go and they end up looking out for each other in the ensuring attempt to survive.

This impromptu friendship lasts until they board the abandoned Dutch vessel in a misguided attempt at escape. While crowded into the ships hold, the Germans begin to open fire, using the ship as target practice. Water begins to leak into the hold, and they realize that they must lighten the load. As the pressures, and water levels, rise, individuals within the group begin to look for people to kick off the boat. The first person they go for is Tommy’s friend, whom they have discovered is a French solider. As the men grow anxious, Alex, one of the soldiers says “Somebody has to get off, so that the rest of us can live.” This statement reflects the mentality of many of the people on Dunkirk. The government was only hoping to get thirty-thousand out of the four hundred thousand men off the beach, and just accepted that the rest of those men would either die or surrender. Tommy, however, has a different opinion. As his comrades try to force the French soldier off the sinking ship, they ask him if them all dying is worth the price of one man. Tommy responds by saying, “I’ll live with it [the price], it’s wrong.” Tommy is unwilling to sacrifice his friend, and despite the pressure put upon him, he does not give in. Tommy’s stand against the cruelty of his comrades is a show of integrity in the face of desperation, much like the rescue of Dunkirk itself.

After witnessing the violent battle and feeling the exhaustion of the soldiers, the aftermath of the rescue is almost a shock. It is too quiet, the men on the train, people going about their lives, Farrier’s landing, it’s almost surreal. On the train, Tommy picks up a paper and begins reading Winston Churchill’s speech. The first words he reads are, “Wars are not won by evacuation” he continues, “Nevertheless, our thankfulness at the escape of our army must not blind us to that what has happened in France and Belgium, is a colossal military disaster.” As Tommy read these words, you can’t help but think of the previous scenes of the movie, of all the people who sacrificed so much so that those men could come home. Of the 338,000 men, whose lives were saved in “a colossal military disaster.” To hear this evacuation summed up in such menial terms is nearly unbearable. One thing that Churchill neglected to address is the importance of this victory to the morale of the people. As the train carrying the army passes through a town, the station is filled with people, handing out beverages, cheering for the men and celebrating the return of their boys.

The power of the story does not come from military might, or superior battle plans, but the actions of everyday people who stand up against tyranny. Tommy, who stands up for his friend. Commander Bolten, who stays behind for the French, and sheds tears for his rescued men. Mr. Dawson, who refuses to turn back so he can rescue just one more man in memory of his son. Farrier, who looks at his empty fuel tank, and continues fighting. Peter, who mercifully lies to the traumatized man who killed his friend when he asks about “the boy”. These people who stood strong are what make Dunkirk great, despite the military loss. The story of Dunkirk is one that will live in infamy, because of people who would not surrender.

0 notes

Text

2017 Essay: Sarah Ekkelboom

Breaking the Circle

Storytelling is an art that has followed human development throughout the ages. Film is one mode of storytelling that has been used in a variety of ways. Some have taken the latent potential of filmography and transformed it into a work of art, a story that speaks to all the senses and conveys a thought-provoking ideology. Denis Villeneuve is a director who is associated with films that focus on a central idea that is larger than mere entertainment. His films are examples of a master storyteller plying his craft. They are filled with significance, using various methods to induce his audience not only to think, but to feel the deeper implications he is trying to expresses. Prisoners and Arrival are two films that show his skill in conveying deep ideas within a suspenseful package. He satisfies the entertainment requirements, while respecting the intelligence of the audience. Within these two movies, we can see the hand of a master. Proving that, while filmmaking may be a collaborative effort, the director uses his position to shape the movie in a way that defines it as his own.

Villeneuve seems to be obsessed with the idea of patterns and violence, and how they might be broken. He is especially interested in how characters respond to traumatizing situations, and how revenge causes a continuation of the cycle. Prisoners is a Villeneuve film that focuses on this idea. The story about the disappearance of two little girls is packed with violent repetitions. There are multiple characters in the film who express this idea in different ways. Keller Dover, the father of one of the kidnapped girls, responds to the incident by placing the blame on someone else, and uses it as an excuse to torture the man for information. Franklin Birch, and his wife Nancy, are the parents of the second kidnapped girl, and are appalled by Keller’s actions. Yet, they do not act to end the man’s suffering. Whether it is through inaction or revenge, people in this film respond to trauma by hurting others, causing the cycle of violence to continue. Near the end of the movie we discover that the person responsible for the kidnappings, is committing these unspeakable atrocities because they experienced the loss of their son. The reasoning behind this action is explained by Holly herself, “Making children disappear is how we wage war with God. Makes people lose their faith. Breeds demons like you.” This is the ultimate violent response to a tragedy, they know that their actions will not bring their son back, yet they spark generations of pain as a form of retribution. The one exception to this rule is Detective Loki, who doesn’t allow his traumatic past cause him to dwell on revenge. Instead, he puts aside his own emotional response so that he can find the truth of the situation and end the cycle of suffering.

The breaking of a cycle is also a prominent theme in Villeneuve’s Arrival. The cycle of human violence is prevalent in people’s response to the arrival of the alien vessels. As the news shows the alien’s appearance, people respond by going crazy. They break into stores, buy up weapons, and generally commit mass destruction. The film, however, follows one person who is willing to look beyond the initial response of violence. Louise Banks, like Detective Loki in Prisoners, is willing to pursue the truth regardless of other people’s opinions. One difference in Arrival is that the cycle is tied with communication and how it connects to violence. The Heptapods communicate with circular patterns, some are complete circles, others are broken. Interestingly, the broken ones include the word for “death” and “human” relating to how they perceive the nature of each. Communication is also prevalent in how the world leaders interact with each other. When the aliens use the word “weapon”, the initial response of each nation is to cease communicating and start preparing for war. This response is exactly the opposite of what is required to solve the problem, thus the cycle of violence continues. Louise, however, does not accept this solution, and risks everything to find the real reason for the alien’s presence. Once she understands why the aliens are here, she does not sit on the information, but she reaches out and shares it with the very person that she could see as an enemy. She also chooses not to fight the inevitable, accepting the heartache that she knows is coming, so that she can still experience the good times. By doing so, she breaks the dominant circle of violence and can unite people and prepare them for the future.

This similar theme is united by the detailed work of Denis Villeneuve, giving us these two wonderful movies with a similar meaning woven into the fabric of the films. In an article about the best shot in 2013, IndieWire references an interview with Villeneuve himself about working on the film. In the interview, Villeneuve mentions how the producer was upset when they spent over thirty minutes just shooting a tree. Villeneuve decided to go with the shot anyway, and it made the best shot of 2013. At the end of the interview, they mention a promise Villeneuve made to himself; that he would, “Keep the liberty of inspired ideas alive.” While the story behind the screen may have remained the same without the director, it is doubtful that the same level of attention would have prevailed. Villeneuve reaches within a story and pulls the deeper ideas to the surface, breaking the cycle of shallow blockbuster films. Perhaps that is the reason he is so interested in the idea of patterns. This is what makes him such a great director, and why his films are some of the best in the industry.

0 notes

Text

2017 Student Writing from FILM 103 - Sarah Ekkelboom

The War for Virtue

The year 1941 was one that contained many conflicting ideas and beliefs that were present in the wake of Nazi Germany. The United States was held in limbo over the issue of Isolationism and foreign warfare. The attitude of the nation at large post WWI was that the cost of foreign involvement was far too high for a nation that was still suffering under the effects of military loss and the Great Depression. The spread of Fascism and German invasion was not considered to be sufficient reason to become involved in another costly war, especially when the chances of that power reaching America was almost nonexistent. This outlook of unconcern held by the American populace is cleverly mirrored in the 1942 movie Casablanca, directed by Michael Curtiz. The protagonist, Richard Blaine, owns a bar located in Casablanca, a place filled with political tension during the terror of World War II. In the film, both the club and the owner maintain a detached neutrality during a loaded political situation. This determined stance causes the character to ignore, and even enable, the atrocities that the Germans committed.

The constant parallels between the hero’s situation, and that of American isolationism show that selfishness and seclusion are traits that are detestable on both the individual and national level. Casablanca displays the character change of a man while giving us an opportunity to have a better understanding of a Country.

The opening scenes of Casablanca explore the general attitude of fear in the city and how that atmosphere affects Rick’s Café Americain. The fact is, the proprietor has chosen to ignore the outside world to the best of his ability. While the city is full of people desperate to escape the oppression of the German army, Rick has a reputation for allowing anyone of any origin into his bar, on the understanding that they leave politics at the door. Politics, however, seem to find their way into every situation. Near the beginning of the film the Nazi army invades Rick’s Café to arrest Ugarte, the man who was responsible for some missing visas. Captain Renault of the German army informs Rick of the arrest and issues a warning not to interfere, Ricks response to this overt threat is the sentence, “I stick my neck out for nobody.” This phrase is repeated throughout the film, and is the philosophy behind Ricks entire worldview. Rick is unaffected by the arrest, even when Ugarte begs for his help as he is drug away. The German officials discuss their invasions with Rick, his lack of response causes Renault to comment that, “Rick is completely neutral about everything.” This attitude that Rick displays reflects the ideas of isolationism in America. While Hitler marches his way across Europe, decimating countries, America’s response is to say that it isn’t their problem because it doesn’t affect them directly. Even though some of those newly occupied countries, like France, were America’s former allies in World War I. Despite their original positions, both Rick and the American nation put aside their Me-First policy and joined in the fight against tyranny.

Rick’s transformation occurs after the arrival of the woman that he loved in Paris who had left him without an explanation. Her presence caused him to recall the past, when he was in love, and evaluate the way that he is currently living. The first show of his true loyalties happens when a distraught foreign young woman approaches him in his Club to ask if Renault could be trusted to get her and her husband out of Casablanca if she agreed to his lecherous bargain. Despite verbally responding in his typical passive manner, Rick proceeds to help the couple, even at the expense of harming his own business. His blatant show of favoritism causes the Germans to retaliate by singing “Die Wacht Am Rhein” in the Café, a reminder to Rick of who has the power in Casablanca. Instead of crumbling under the threat, or simply remaining neutral, Rick allows his band to strike up the French song “Marseillaise” thus proclaiming his true loyalties to the allied forces. Renault tells Rick later in the Film that Rick, “You are not only a sentimentalist, but you’ve become a Patriot.” This idea of selfless risk carried over to his act of sacrifice for the greater good of a global cause. Rick’s conversion is an allusion to the American mindset in 1941, the date that is shown on the check Rick signed at the beginning of the film is no coincidence. December 2nd 1941 was only five days before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The assault forced America to join the allies in the War, tipping the scales in their favor.

The situation of Rick’s café in the town of Casablanca is an example of how neutrality in the face of oppression is impossible. Each of these examples has an application beyond WWII, everyone is faced with a choice like this one, where it is tempting to ignore what we know to be right so we can continue without any interference with our own existence. Eventually there will come a time when a choice must be made, the only question is our response to it.

0 notes

Text

Titles Screened in FILM103 - Autumn 2017

Raiders of the Lost Ark

0 notes