Text

I can laugh about this now, but at the time I was 31, which felt old for a musician. I had come through playing with Treebound Story, Pulp and Longpigs. I’d quit heavy drugs, got married, launched a solo career and been dropped by my label. I had been on tour constantly, making very little money, been brutalised by the industry to an extent and away from my family for a lot of time. All these thoughts fed into The Ocean.

youtube

0 notes

Text

7/17/25

Discomfort is a sacred site--

Patrycja Humienik, "On Belonging"

0 notes

Text

Modernism, in all its tragic beauty, is a language that reconciles the fleeting and the eternal. That shows us how nothing lasts, yet everything matters.

0 notes

Text

Howardena Pindell

Autobiography: Scapegoat

1990

0 notes

Text

7/12/25

"As we will come to see, there are at least three kinds of grief: "relational grief," which marks a fractured relationship; grief at the harm that befalls someone who dies; and grief at the sheer loss of life. These forms of grief may interact and coincide, but they are not the same. Each of them hurts in different ways and each says something different about love."

--Kieran Setiya, Life Is Hard: How Philosophy Can Help Us Find Our Way

0 notes

Text

7/12/25

Initiation—

Denise Levertov

Black,

shining with a yellowish

dew

erect,

revealed by the laughing

glance of Krishna’s eyes:

the terrible lotus.

1 note

·

View note

Text

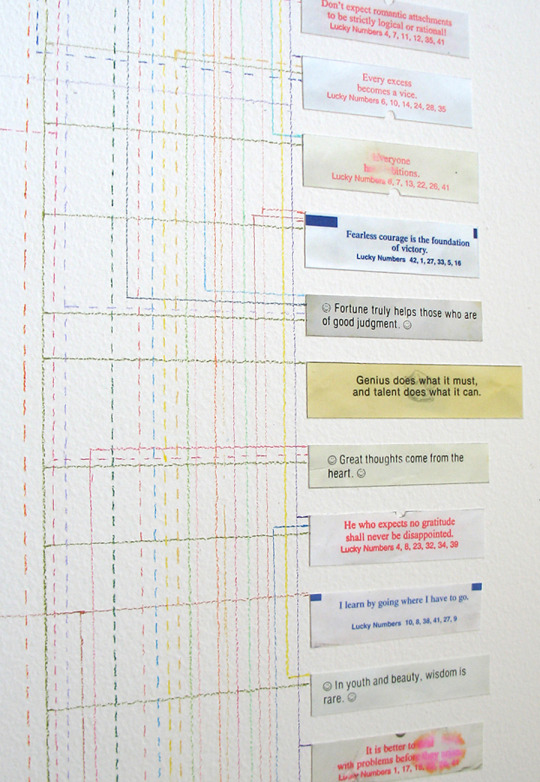

Lisa Young

Fortune Wall (detail)

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

7/11/12

Narcissus to Achilles-

Frank Stanford

Yesterday, I passed over a bridge

and saw a boot underwater.

Such thoughts I had,

I cannot tell you.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Even if the stadium is actually built, and the low-budget A’s do land in Vegas, there are even more issues waiting. Despite the 40 million visitors that Las Vegas counts annually, the A’s will have to fight to fill seats while competing with live entertainment and nightlife, gambling and the NFL’s Raiders and the NHL’s Golden Knights, at least for a few months a season, all inside their tiny market. So with all that said, why didn’t the A’s fight to play at least some games at the local minor-league park and try to get some grassroots support going? It’s just another confounding move by Fisher, who made the shortsighted move to play in Sacramento in order to keep revenue from his local television deal.

Meanwhile, over in Sactown, not only are the A’s not selling out their small minor league park, but their failure to take the capital’s name and embrace the city in any tangible way has alienated fans in what’s meant to be their home for three years. Not to mention that players are already fed up with their substandard ballpark. Bradbury speculates that with all the bad will surrounding the club, they could wind up in Salt Lake City or elsewhere next season. So now Fisher is, and let’s say it politely, disliked, in multiple cities. And should the stadium deal in Las Vegas unravel, it would make for a unique trifecta.

That leads to the final question. Why? Why would a billionaire go through all these trials and travails for a move that seemingly doesn’t add up, practically or fiscally? We know the then-Oakland A’s needed some sort of stadium deal in place by 2024 in order to keep their slice of MLB’s revenue sharing stream, but that doesn’t begin to explain it.

“This is the dog catching the car,” DeMause says. “And now that he has caught the car, I don’t think he had any idea what to do with it. He switched up on stadium sites [in Las Vegas] in a matter of 24 hours. He did not have a plan for where to play once Oakland kicked him out, even though he didn’t have a lease. It either didn’t occur to him or he figured he would figure it out later.”

The case against Fisher is damning, yet instead of selling and walking away with a tidy profit, he soldiers on. Is it a case of a wealthy team owner thoroughly enjoying the attention of desert-based suitors after years of combat with Oakland’s leaders? Is it a case of an heir on a quest to prove to someone, maybe himself, that he has the chops to pull something like this off? DeMause believes it’s all possible, but offers up a simpler explanation.

“It’s very, very clear: he’s really bad at this.”

0 notes

Text

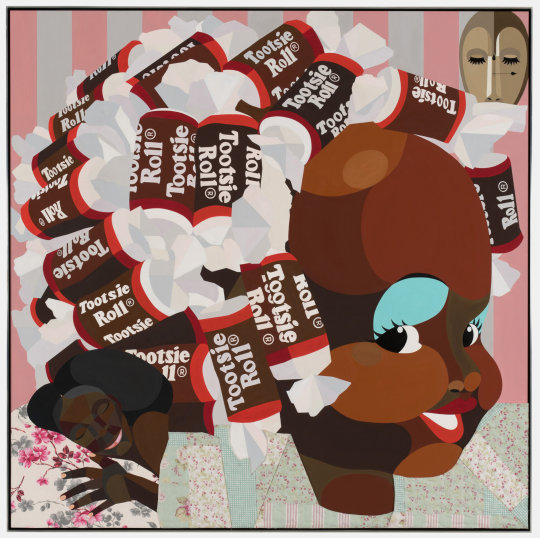

Derrick Adams

Only Happy Thoughts

2024

It’s just, when you’re a Black person making art, there’s nothing you can do that’s not seen as political. But that frees me up. I actually make what I want and have fun, and I don’t really have to think about being political because I’m always going to be political. How political I am is also going to be a debate. A Black woman I paint on a floaty is going to be seen very differently than a white woman on a floaty by Alex Katz.4 It’s going to be about the politics of leisure and the way that Black people have been denied certain things.

1 note

·

View note

Text

7/8/25

"The habit of dwelling on victimhood dulls the impulse of self-correction."

Timothy Snyder, On Tyranny

1 note

·

View note

Text

7/8/25

We know so much that we don’t know we know about each other. We always know each other’s class.

--Janet Malcolm,

Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory

0 notes

Text

#the rice place#derek hunter wilson#ash yang#sara guest#diana oropeza#melissa amstutz#fonograf editions

0 notes

Text

Love me the way I love you

Wehner: Sometimes doing the next thing is the best thing to do. You wrote a book on Fyodor Dostoyevsky. He’s one of the writers who have meant the most to you, and it’s understandable why. What is it about the work of Dostoyevsky, in particular, that has so impressed you in the context of faith? How has your theology been shaped by him?

Williams: I discovered Dostoyevsky as a teenager and read him fairly intensely as a student and as a graduate student. What struck me most was two things. One is he’s very good at depicting characters who are holy, who are in some sense transparent to the divine and also letting you see that they’re not going to have all the answers. They’re going to be the window that lets the light in. And I thought, “That tells me something about holiness. Don’t look for the leader, the controller, the problem solver. Look for where the light gets in.” In Leonard Cohen’s famous image, the persons who are part of the crack that lets the light in.

Throughout my life I’ve been privileged to see a number of individuals in whom I could say, “Yes, there’s the crack. They’ve let the light in.” They’ve been people of varied accomplishment or status, but the one thing in common is things look different in their light. So that was one thing I learned from Dostoyevsky.

I suppose the other thing was Dostoyevsky’s absolutely relentless commitment to making it as difficult for himself as he possibly could. He says: You want the grounds for atheism? I’ll tell you the grounds for atheism. Let me lay out to you all the good reasons for not believing in God.

Of course, in the famous chapters in “The Brothers Karamazov” where Ivan Karamazov talks about the suffering of children, that’s Dostoyevsky saying: Let me show you. You think you have reason for not believing? I can show even better reasons for not believing. And pushing through that, saying: I’m not going to pretend it’s simpler than it is. And saying at the end of that: I’m not going to pretend to give you an answer. I’m going to give you the fact that love is possible in the middle of this.

The moment of reconciliation, of love, of forgiveness, of acceptance is as real as all the nightmares that he describes. Dostoyevsky, as it were, flings down his pen and says: Well, there you are. You make your choice. The world is full of evidence against love, against reconciliation, against the possibility of a God who holds the world.

The probabilities stack up in a fairly unpromising way, and then a moment happens where the light gets in, where something in the world refuses to be crushed by that.

Nick Cave, the singer and songwriter, with whom I had a long conversation a couple of years ago, spoke about the impact on him of the tragic death of his teenage son. He said his main feeling was not that it made faith harder but that it made faith more imperative: I’m not going to be defeated.

I think there’s something of that in Dostoyevsky, when at the end of that astonishingly painful and difficult section of “The Brothers Karamazov” Alyosha kisses his brother. It’s as if Dostoyevsky is saying: Well, that is as real as any amount of suffering. Make what you will of it. I’m not going to tell you, but there it is.

Wehner: Let me stay on Dostoyevsky for a moment, because, as you said, his indictment of God was so searing in “The Brothers Karamazov” that he wasn’t even confident that he’d adequately refuted it. That raises the issue you touched on, which is theodicy, the effort to resolve the problem of evil with the existence of an all-powerful and all-benevolent God. You touched on this in your answer, but I want to home in on it a little bit more. What is Dostoevsky’s response to suffering? If I understand you right and if I’ve read Dostoyevsky correctly, the answer is not philosophical or theological. It’s primarily love. How would you respond to people who ask this ancient question: Why does a good God allow the innocent, the children, to suffer?

Williams: The question I want to ask in reply — though, of course, I can’t ask it in quite these terms if somebody is actually in the middle of suffering — is: What would a satisfactory answer to that look like? What would our lives be like if I could say, “I’ll tell you exactly why your child died. I’ll tell you exactly why you suffered that terrible accident. I’ll tell you exactly why people are dying daily in Ukraine and Gaza and Congo. I can tell you, and it’ll all be clear, and you won’t have to worry about it any longer.”

What would that feel like? When people say they want an answer, it’s not that kind of answer they’re really looking for. I don’t know entirely what to make of that. But whenever people say, “Have you got an answer?” I say, “Do you really want that kind of answer?” Imagine the bereaved mother turns up at the parsonage door and says, “Why should my child die?” And you say, “Because of this, this and this. Satisfied? See you next week.”

No, that’s not it. And what is “it”? I don’t entirely know, except that people live with these horrors. People make personal sense of them. People are sometimes opened up by them to depths they hadn’t expected. That’s, again, as Dostoyevsky would say, it’s as much a part of the fabric of the world as anything else.

The other dimension was that he’s always nudging us to ask, “You talk about suffering. So what’s your complicity in this?”

He invites you to understand that you are part of the problem. You’re part of what tangles and embroils the world more and more in injustice and suffering. Just step up to that and say, “Yes, I’m part of this. I’m responsible. I’m answerable for the neighbor.” We’re not just talking about love in a vague and general way, but as he put it and as the great Dorothy Day liked to quote, this is a “harsh and dreadful love.” This is asking something really quite frightening of you, that you understand your solidarity in this.

Wehner: I imagine what some people might ask, what Ivan Karamazov might ask, isn’t simply, “Tell me the reason that this happened.” It might be, “Why did you allow it to happen in the first place?”

Williams: Of course. It essentially has to do with the basic question of why there is anything other than God. Because anything other than God is going to be, in some ways, unstable, in some ways flawed. If God made the perfect, God would make another God. So why does God invest in what isn’t God? And not being God, I don’t have a very clear sense of the answer to that, nor do any of us.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/08/opinion/jesus-faith-god-compassion.html

0 notes

Text

For all that humanity has learned about the universe, the vast majority of this cosmic plane in which we exist remains in the dark. The best theory yet describes a universe in which the galaxies, the stars, the planets and all of us make up only 5 percent of all the matter and energy there is. The other 95 percent is dark matter, an invisible substance that glues everything together, and dark energy, an unknown force ripping the universe apart.

Vera C. Rubin, the astronomer whom the Rubin Observatory is named after, uncovered evidence of dark matter in the 1970s. By studying the swirling motion of galaxies, driven by the gravity of the mass within them, she deduced the existence of a type of matter that could not be directly observed by telescopes, because it did not emit, reflect or absorb any light.

In the decades since, theoretical physicists have come up with countless ideas about the composition of this so-called dark matter. Experimental physicists have built ever larger detectors in an attempt to observe it directly, so far to no avail. All the while, astronomers have helped narrow the possibilities of its nature by relying on increasingly powerful telescopes that measure how dark matter influences the structure and motion of the universe that can be seen.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/19/science/telescope-vera-rubin-dark-matter.html

0 notes

Text

6/24/25

if a crow—

Ian U Lockaby

then a black ice cube pressed

against the grain of the sun

while the afternoon mugs drop

pattering spoils of a milk’d black coff-

in the over grown carpets

lay a caffeinated belly bitter against

the sleep against the damn

bright slipping away. If a crow—

remembers you,

by what:

Something growly

in the vanilla leaf—

don’t dawdle now

it’s plenty late

1 note

·

View note

Text

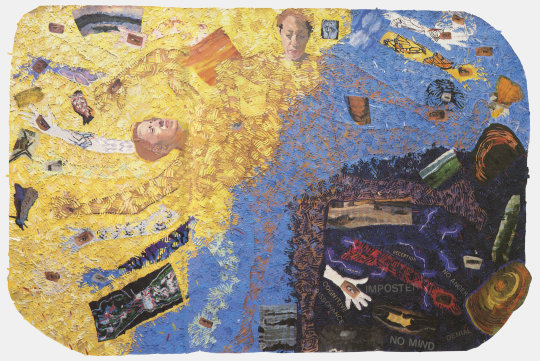

Howardena Pindell

Autobiography: The Search (Chrysalis/Meditation, Positive/Negative)

(1988-89)

0 notes