jaye, she/they. sideblog for rgu, oniisama-e & other gl. // [prev: asakareiism, juriism]

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

This is the Page of Pentagrams I made for the Utena Tarot Project that got cancelled. I really liked drawing Anthy's hair.

365 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jeongnyeon x Jooran: Goodbye my one and only Prince

The ending of Jeongnyeon break my heart so much 💔 and this is my take on deleted kiss scenes between Jeongnyeon and Jooran from unedited script

Jooran (in a trembling voice):

"Goodbye, Jeongnyeon. My one and only prince. "

Jeongnyeon's heart feels like it will stop, and the sight before her eyes is dizzying.

Jooran looks at Jeongnyeon with trembling eyes and kisses her.

The first and last, infinitely trembling and heartbreaking kiss.

-- Jeongnyeon uncensored script collection, Volume 2, Episode 11

“The tragedy of the two is that only at the moment of kissing does Jeongnyeon realize that she also loves Jooran. Ah... it wasn’t friendship.”

-- writer Choi Hyobi, in the commentary book of Jeongnyeon’s script collection.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

juran yearning for jeongnyeon even years later bc she promised never to forget her

(they continue yearning for each other for years until one day juran's shitty husband suddenly dies prematurely in a freak accident and then juran runs away and finds jeongnyeon and they reunite)

1 note

·

View note

Text

gonna convert this blog to a general GL blog including korean gl bc i have nowhere to post about jeongnyeon.

0 notes

Text

Kaoru will just drop the most insane devastating romantic lines of all time and then she and everyone else has to pretend like it’s fine. most unfine situation ever methinks

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

goodbyes are hard, and they're hard, and they're hard

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

I am coping

158 notes

·

View notes

Text

おにいさまへ… / Oniisama E / Dear Brother

Osamu Dezaki

1991

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

wanted to try going something.

389 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finished oniisama e and will now launch myself off a cliff

#THANK YOU OP THANJ YOU THABK YOU#oniisama e#kaorei#orihara kaoru#asaka rei#oniisama e fanart#kaoru x rei#rei x kaoru

650 notes

·

View notes

Text

<3

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

Revolutionary Girl Utena: Gender in Context

beneath the cut, I discuss the RGU's portrayal of gender in the context of 1990s Japan.

in Ikuhara's interview with Mari Kotani, he stated that in traditional Japanese society, "prince" meant "patriarch." the same is true in Western societies--there was a time when a prince would be an heir to a royal line. by 1997, this meaning had died out of large parts of the world. even the association between princes and traditional masculinity was fading. Saionji, the weakest, most pathetic man in the show, is a parody of historical Japanese masculinity, with his kendo and his blatantly regressive beliefs about women.

in RGU, prince may still mean patriarch, but in a far more subtle fashion. Ikuhara and Kotani discussed the changing expectations for men in the latter half of the 20th century--it became gauche to fight over a woman with one's brawn, so instead, power struggles were played out in the arena of looks and sex appeal. one can see this reflected in the character Akio, whose power as a prince arises from his ability to turn "easy sensual pleasure based on dependency" "into a selling point with which to control people."

Akio has his moments of showboating masculinity, but when preying on Utena, he operates by making himself seem non-threatening and soft.

not only that, but he purports to want to allow students to express their individuality and thus approves of Utena's masculine form of dress. this is a front--by the end of the show, he's telling Utena that girls shouldn't wield swords. thus, through Akio's character, the show argues that traditionalist patriarchy in Japan isn't gone, but instead has only been papered over with false progressivism.

with all that said, there seems to be more to the character. he's taken the family name of his fiance, Kanae, and whatever material power he has in the school is dependent upon her family. in Japanese society, this is considered a humiliating position to be in, something that only a shameless man would do. the show never gives the audience any insight into how Akio feels about this--is he unbothered entirely, or are his actions against the Ohtori family an expression of his repressed anger? does he harm the children under his care to compensate for his humiliation?

this aspect of Akio's character may seem irrelevant in light of the larger, immaterial social forces at work in the show. however, I would argue that it was included for a reason. Akio, despite his status as ultimate patriarch of Ohtori, is in fact a highly emasculated character, to the point where lead writer Enokido even said that he is driven by an infantile mother complex.

to explain why Akio was portrayed this way, we have to discuss Japanese history. the nation suffered a major defeat in WWII and was forced to accept whatever terms the United States laid out for it. for an examination of how the Japanese have never truly processed those events and have plunged into modernity with reckless abandon, I recommend Satoshi Kon's Paranoia Agent. to sum it up briefly, in a very short period, the nation regained its economic footing, and by the 1980s had the largest gross national product in the world. this economic boom may have allowed Japan to maintain a sense of sovereignty, dignity, and power, but it was inherently fragile.

the infamous "bubble economy" lasted from 1986 to 1991. during this time, anything seemed possible; financial struggles appeared to be a thing of the past, and capitalist excess reached new heights. the ghosts of this period can be felt across Japanese media; for instance, think of the final shot of Grave of the Fireflies (1998), where the two dead children look down on Kobe, glowing an eerie green to imply its impermanence. the abandoned theme park from Spirited Away (2001) is explicitly referred to as a leftover from the previous century, when many attractions were built and then tossed aside in a few short years.

the bubble popped in 1992, leaving an entire generation feeling cheated. the bright futures they'd been promised, which had actually materialized for their parents and older siblings, had been lost to them overnight. economic crises are often accompanied by gender panics. to quote from Masculinities in Japan, "The recession brought with itself worsening employment conditions, undermining the system of lifelong employment and men’s status of breadwinners in general. The unemployment rate was rising, and although it never reached crisis levels, men could no longer feel safe in their salaryman status. Their situation was further complicated by the rising number of (married) women entering the workforce."

with this in mind, Akio's character can be taken as a representation of masculinity in crisis in 90s Japan. he's forced to rely on women for his position in life and has failed to save his only relative, Anthy. he tries to escape his misery through hedonism, perhaps an allegorical representation of how men tried to maintain their old standard of living after the economic bubble burst.

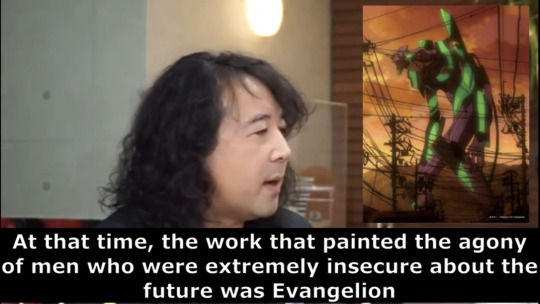

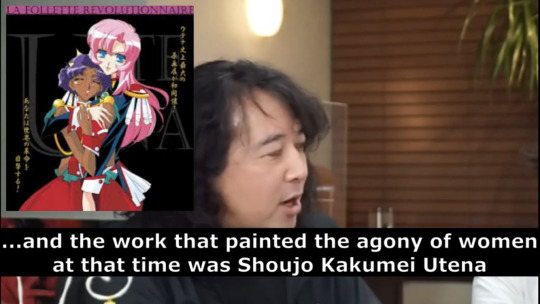

but of course, Akio is not the main character of RGU--the story is about girls. mangaka Yamada Reiji discussed the series in the context of the 90s, stating the following:

while I opened this essay by discussing the prince, the same points could be made about the princess. despite the increasing irrelevance of royalty, princess is still an important concept. how does it relate to the socioeconomic landscape of the 90s?

in Yamada's view, RGU is full of relics of the 80s; for instance, the figure of the ojou-sama, an entitled young woman who never lifts a finger for herself. during the economic bubble, it was increasingly common for women to be entirely taken care of by the men in their lives. Yamada names Nanami as a clear ojou-sama type character: she weaponizes her femininity, demanding to be rescued, doted on, and served.

however, by 1997, the ojou-sama could no longer expect to get what she wanted. from the 80s to the 90s, the percentage of women in the workforce increased around 15%; it was no longer viable for most women to be "kept" by their families. as the men experienced the humiliation of not being able to provide for their wives and children, women were undergoing a disillusionment of their own.

Yamada blames Disney for creating the ideological structure which led women astray. obviously, the company is known for its films about princes rescuing princesses. in Yamada's recounting, during the 80s, the company was infiltrating Japan through its theme parks as well; across the country, Disneylands were opening up and people were buying into the escapism the corporation offered. Japan, as America, became a country of eternal children. its people were waiting for a prince to appear and save them.

but fairy tales can't stave off reality forever. Yamada claims that RGU embodies the rage of young women who woke up one day and realized that they had been raised on a lie. this anger pervades the work from beginning to end.

though RGU was created in a particular social context, its lessons can be extrapolated to any time and place. as the first ending tells us:

I hope this essay helped provide more context for the series. thanks for reading!

910 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Guy She Was Interested in Wasn’t a Guy At All - Oosawa icons

139 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Guy She Was Interested in Wasn’t a Guy At All - Oosawa icons

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Guy She Was Interested in Wasn’t a Guy At All - Oosawa icons

188 notes

·

View notes