Text

Tumblr Multimedia Journal Assignment 3: The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson

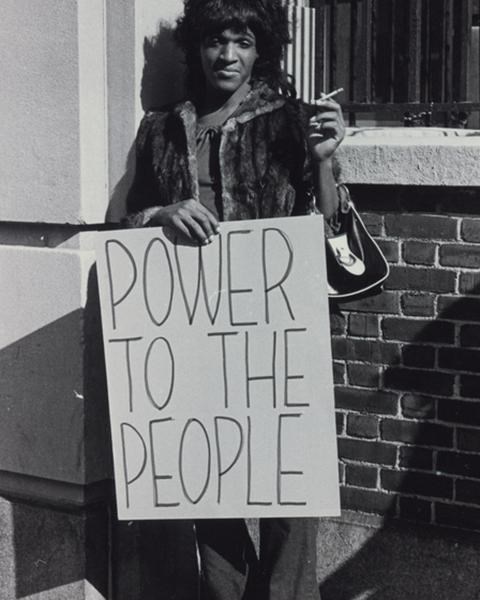

The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson is a Netflix documentary film directed by David France. The film tells us about the lives of Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, who were in the frontlines of the LGBTQ+ movement in New York when it first began. One of the film’s central themes is Marsha P. Johnson’s death in 1992 and activist Victoria Cruz’s attempts to investigate it. Police initially said that Johnson’s death was a suicide but her close friends and followers insisted that she would not commit suicide and suggested there was foul play in her death. Several witnesses had come forward with information that could have been vital to Marsha’s case but law enforcement ultimately kept the cause of death as a suicide. Later in 2002, Johnson’s case was reclassified and the cause of death changed to undetermined.

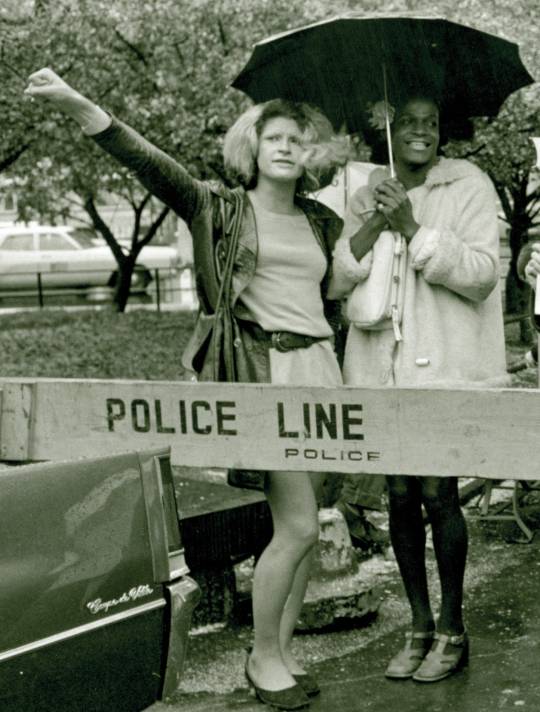

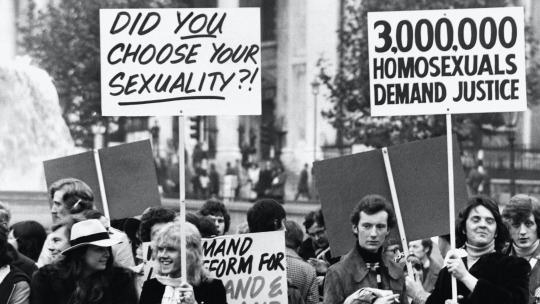

Johnson was a central figure in NYC’s gay liberation movement for over two decades, she advocated against oppressive policing and along with Sylvia Rivera, helped found Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), which was a group that facilitated housing for homeless, transgender youth. Although at the time, the term “transgender” was still not widely used, Johnson has become one of the most important images when discussing trans rights and the trans movement. Marsha was a key figure in the Stonewall riots, possibly the most important event that ended up launching the gay liberation movement. The Stonewall riots were a series of protests that began when police raided gay bars in New York’s Greenwich Village and the community fought back. In 1970, a year after the protests, the first gay pride parade took place. Activists like Rivera and Johnson showed concern for the discrimination and violence that trans people faced and who often had to go into sex work as a means to stay afloat. At the time there weren’t really any type of resources that helped or protected LGBTQ+ youth, specifically trans people of color. People like Johnson and Rivera were active in consistently aiding marginalized communities.

Marsha P. Johnson laid the foundation of the LGBTQ+ movement that we are so familiar with today. However, and especially for the trans community, there is still a fight for fairness and equality that hasn’t been resolved. This year alone, 350 transgender people have been killed, a fifth of them in their own homes. A disproportionately large number of the deaths were of transgender women of color, specifically Black. Even after their deaths, the trans community continued to be disrespected with misgendering and insensibility in police statements and media reports. On the other hand, we are able to see more, although still limited, LGBTQ+ representation on popular media with shows like Netflix’s Pose and Orange is the New Black, both examples giving well developed story lines and complexity to their trans characters. The majority of trans representation on media however, is predominantly negative. It’s a trend that trans characters are usually cast as a victim, they’re portrayed as sex workers, or other characters made constant use of anti-trans slurs and language. There is still an overwhelming amount of work to be done. In an interview for Out of the Closets: Voices of Gay Liberation, Johnson said her ambition was “to see gay people liberated and free and to have equal rights that other people have in America.” There is still a lot to fight for in order to see Johnson’s ambition through.

GLAAD. “Victims or Villains: Examining Ten Years of Transgender Images on Television.” GLAAD, 12 Jan. 2017, www.glaad.org/publications/victims-or-villains-examining-ten-years-transgender-images-television.

Jaworowski, Ken. “Review: 'The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson' Explores a Mystery.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 5 Oct. 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/10/05/movies/the-death-and-life-of-marsha-p-johnson-review.html.

Maxouris, Christina. “Marsha P. Johnson, a Black Transgender Woman, Was a Central Figure in the Gay Liberation Movement.” CNN, Cable News Network, 27 June 2019, www.cnn.com/2019/06/26/us/marsha-p-johnson-biography/index.html.

Nowakowski, Audrey. “'The Death And Life Of Marsha P. Johnson' Shows Fight For Social Justice Isn't Finished.” WUWM, 24 June 2020, www.wuwm.com/post/death-and-life-marsha-p-johnson-shows-fight-social-justice-isnt-finished.

Wareham, Jamie. “Murdered, Suffocated And Burned Alive – 350 Transgender People Killed In 2020.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 28 Nov. 2020, www.forbes.com/sites/jamiewareham/2020/11/11/350-transgender-people-have-been-murdered-in-2020-transgender-day-of-remembrance-list/?sh=530141e765a6.

Young, Allen, and Karla Jay. Out of the Closets: Voices of Gay Liberation. New York University Press, 1992.

0 notes

Text

Tumblr Multimedia Journal Assignment 2: When They See Us

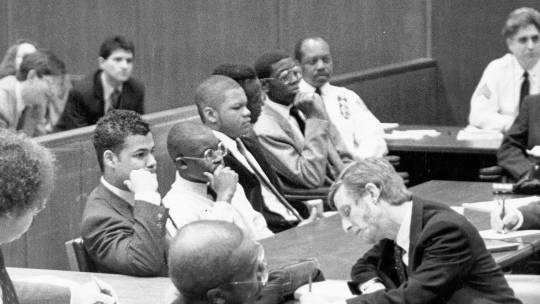

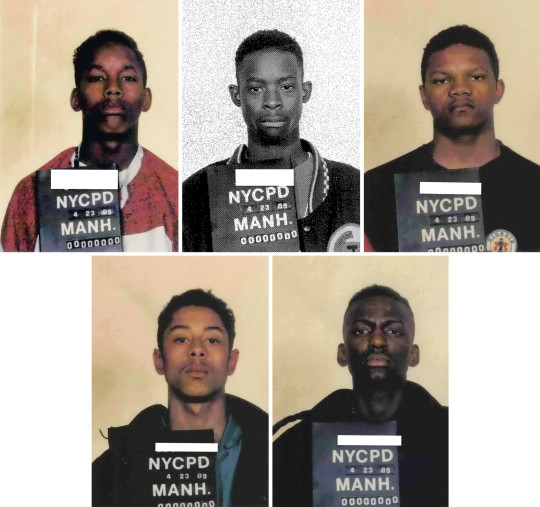

“When They See Us” is a four-part Netflix miniseries written and directed by Ava DuVernay. The series tells the story of the Central Park jogger case, which took place in 1989. The events occurred on April 19, 1989, where more than thirty teenagers were creating a disruption in New York City’s Central Park. Some of the teenagers took part in different attacks, assaults, and robberies against people who were at the park. Many of the victims filed police reports: several cyclists were attacked, cab drivers were thrown rocks, and a pedestrian was robbed and left unconscious. On the same night, a white female jogger was violently raped and assaulted. She was knocked unconscious and dragged off of the road, where the assault itself took place. She was left, beaten almost to death, and her body was discovered almost four hours later. The victim, who remained anonymous for 14 years, and was referred to as the Central Park jogger, was a woman named Trisha Meili, a 28-year old banker. Her injuries were so severe that she remained in a coma for twelve days. When she woke up, she couldn't talk or walk and to this day, still has no memory of the attack. On that night, twelve arrests were made. Five of the boys who were arrested included Korey Wise, Yusef Salaam, Raymond Santana, Antron McCray, and Kevin Richardson, all between 14 and 16 years old. They later became known as the Central Park Five. Each of them were interrogated for at least seven hours. For most of them, a parent was not present throughout the whole interrogation although they were all minors. The police violently coerced confessions out of them, which were videotaped and later used during their trials. At the end of their trials, Salaam, Santana, Richardson, and McCray were all sentenced to 5-10 years. Korey Wise, who was 16 at the time, was tried and sentenced as an adult (5-15 years.) Matias Reyes, Meili’s real assailant, eventually confessed to the crime and the Central Park Five were cleared of all charges after having almost served the entirety of their sentences.

“When They See Us” very accurately represents the racial hostility that predominated New York City during the 1980’s. At the time the Central Park Five were tried, they weren’t seen as human beings. Through many people’s eyes, these young boys were animals, savages that hurt and traumatized a young, educated white woman. Donald Trump, a character we are extremely familiar with today, went as far as publishing an ad in the New York Times asking that these boys be executed. It was a full page ad with the headline “Bring Back the Death Penalty”, costing him $85,000. He wrote “I want to hate these murderers and I always will. I am not looking to psychoanalyze or understand them, I am looking to punish them.” In an interview around the time of the case, he said “Maybe hate is what we need if we’re gonna get something done.” A grown man said these things about five teenage boys who had no real scientific evidence against them, and who were always innocent. If their case had taken place earlier in the 20th century, it is incredibly possible that they would have been part of the large group of black and brown people who were lynched. Ava DuVernay, writer and director of the series, does an exceptional job of humanizing the Central Park Five. Although some parts were fictionalized for purposes of the show, the young boys and their families are accurately represented and so are the injustices they had to experience. This case took place in the 80′s, yet we see parallels and similar situations happening in more recent times. Black and brown people have historically been dehumanized and treated unfairly by the criminal justice system. There is an oppressive system in place that puts black and brown people at the very bottom of the social hierarchy. Referring to Peggy McIntosh’s “Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack”, she mentions that the system works to favor white people and disadvantage POC. Maybe if the Central Park Five were white, privileged boys, coming from “better” parts of the city, the outcome of their trial would have been very different. Maybe they wouldn’t have even been arrested in the first place.

Unfortunately, this case resonates a little too closely to the type of mistreatment of black and brown people we continue to see today. This is something that has been happening continuously throughout history. How different is lynching to young men being unfairly tried for a crime they didn’t commit, or to unarmed and innocent black people being murdered, many times by those who are supposed to keep our communities safe? In the case of the Central Park Five, it’s interesting to note that they were humanized a large part of the public only after they were exonerated. Yet in the case of white people committing similar crimes, they are usually given the benefit of the doubt. When news reports come out about white people committing similar crimes, the pictures shown are not mugshots; they’re senior portraits, photographs with their families, pictures of them looking accomplished at athletic events. For them, it is “innocent until proven guilty.” In “Picture Us”, Willis mentions the importance of mundane and ordinary representation black people, something that feels difficult to achieve even today. Imagine how difficult it was, and continues to be, for young black and brown people to see images of themselves only for negative reasons. It is a constant reminder that they are seldom seen as youths with infinite potential, but more often potential criminals and troublemakers. In the case of Korey Wise, he was judged for the way he spoke, and the reason was simplified to him not wanting to attend school. In reality, the case was that he refused to attend class because of the bullying he faced. Again referencing Peggy McIntosh’s “Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack”, #2 on the list is “I can avoid spending time with people whom I was trained to mistrust and who have learned to mistrust any kind of me.” Korey Wise, Yusef Salaam, Raymond Santana, Antron McCray, and Kevin Richardson could not afford that privilege.

Dwyer, Jim. “The True Story of How a City in Fear Brutalized the Central Park Five.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 30 May 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/05/30/arts/television/when-they-see-us-real-story.html.

Hamilton, J. Christopher, and Donovan R. Roy. “When They See Us: An Unshaken History of Racism in America.” Wiley Online Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 6 Mar. 2020, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jftr.12360.

Herzog, Kenny. “Where the Key Characters From When They See Us Are Now.” Vulture, 14 June 2019, www.vulture.com/article/when-they-see-us-central-park-five-now-explainer.html.

Mcintosh, Peggy. “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack (1989) .” On Privilege, Fraudulence, and Teaching As Learning, 2019, pp. 29–34., doi:10.4324/9781351133791-4.

Paul, Deanna. “'When They See Us' Tells the Important Story of the Central Park Five. Here's What It Leaves out.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 29 June 2019, www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/06/29/when-they-see-us-tells-important-story-central-park-five-heres-what-it-leaves-out/.

Tillet, Salamishah. “'When They See Us' Transforms Its Victims Into Heroes.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 30 May 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/05/30/arts/television/when-they-see-us-netflix.html.

Willis , Deborah. “Introduction: Picturing Us.” Picturing Us: African American Identity in Photography, Diane Publishing, 2006, pp. 3–26.

0 notes

Text

Tumblr Multimedia Journal Assignment 1: #OscarsSoWhite

1.What is the subject of your film, program, or internet/social media selection? Provide a brief summary, describing your selection and how it relates to our course topics, readings, and screenings.

2.Referring to related and appropriate readings and screenings from the course, describe how your selection represents racial and ethnic identities (and if applicable, intersectionality). In what ways does this media generate a conversation regarding race, ethnicity, and cultural diversity?

3.How does your selection relate to the course readings, screenings and discussions? Reflect upon the representation and circulation of racial and ethnic identities in popular visual culture. Your reflections should be attentive to the intersectionalities of race, ethnicity, sexuality, religion, socioeconomic class and gender

4.Include Images, video,audio,links or other media elements for your selection.Make sure you cite everything you use. Please make sure to use either MLA or Chicago 16th Style for citations. The more media-rich the post, the higher the grade.

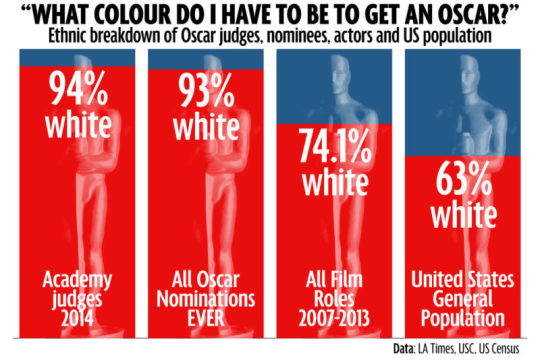

The first media selection I will be writing about is the hashtag #oscarssowhite. April Reign created the hashtag five years ago when the nominees for the 2015 Oscars were announced. All 20 acting nominations were given exclusively to white actors. In 2015, the Academy membership was overwhelmingly white and male (92% and 75% respectively.) Reign was watching the nominee announcement one morning while getting ready for work and immediately noticed the lack of diversity, prompting her to tweet “#OscarsSoWhite they asked to touch my hair.” This created a snowball effect of more tweets: “#OscarsSoWhite they wear Birkenstocks in the wintertime.” and “#OscarsSoWhite they have a perfect credit score.” Franklin Leonard, the founder of Black List, noted that this was only a year after “12 Years a Slave” won and how minority communities felt they were led to believe that there had been a real change in the white-washed Hollywood industry. In 2015, there also weren’t any women directors nominated or any visibly disabled people, so although #oscarssowhite directly refers to race, it’s really about the underrepresentation of all minority groups. This has been a common trend from our class materials. White people are constantly put in the center of all the media we consume, in television and in movies. We are constantly being taught that white means neutrality, a white person could be anything. They can play characters that are complex and are given proper arcs and development and their race has absolutely nothing to do with it.

Something that is interesting to note is that in the Oscars, the few women that have been nominated for best actress or supporting actress, a large part of them are playing roles of women going through hardships, or women who have lived a life full of struggles. Cynthia Erivo was nominated for the role of Harriet Tumban in “Harriet” in the 2020 Oscars. Erivo portrayed the life of a woman born into slavery who escaped and became an abolitionist and political activist. In 2014, Lupita Nyong’o won best supporting actress for her performance in “12 Years a Slave” but got snubbed from even a nomination for her part in Jordan Peele's critically acclaimed horror movie “Us.” Nyong’o faces the task of playing two completely separate actors, so what’s the difference between her characters in both movies? Trauma. I feel like this relates closely to Dyer’s “On the Matter of Whiteness.” Lupita Nyong’o gets recognition from the Academy when she plays a character based entirely around her race (and the suffering that came as a result), but when she plays a fully realized, multifaceted character (two actually) in “Us”, a nomination is not merited. This goes back to the tradition of white representing relatability and neutrality and non-white meaning a representation of their race.

There’s a trend of seeing nominations for Oscars throughout the years being predominantly about the experiences and lives of straight white men. With the larger part of the Academy being that demographic, we can infer that many times, the way they choose actors and films to nominate, it has to do with the lens they view it through. Perhaps if the Academy was more inclusive in its members (more women, more people of color, more people from the LGBTQ+ community), Oscar nomination lists would look much more different. Through the entirety of the Oscars (over 90 years), only a total of five women have ever been nominated in the category for best director and out of all of them, only one has won, being Kathryn Bigelow for “The Hurt Locker” in 2010. There have been some changes in the Oscars since 2015. In 2020, Bong Joon-ho’s “Parasite” made history by being the first non-English film to win best picture, and also getting five other awards, including best director and best original screenplay. However, none of the nominations went to the cast despite their top tier performances. Also in 2020, Greta Gerwig was snubbed in the best director category for “Little Women.” Gerwig was nominated in 2018 for “Lady Bird”, being the only woman nominated for best director in the last decade. In 2019, three out of four of the acting categories were won by non-white actors (Rami Malek, Mahershala Ali, and Regina King.) Since the start of #oscarssowhite, the Academy has doubled the number of POC members from 8% to 16%, which is still ridiculously low. Incredible directors and films with representation and diversity continue getting snubbed by the Academy (Kasi Lemmons for “Harriet”, Lulu Wang for “The Farewell”, Lorene Scafaria for “Hustlers.”)

In Peggy McIntosh’s list at the end of “Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack”, she includes:

6. I can turn on the television or open to the front page of the paper and see people of my race widely and positively represented.

12. I can go into a book shop and count on finding the writing of my race represented, into a supermarket and find the staple foods that fit with my cultural traditions, into a hairdresser’s shop and find someone who can deal with my hair.

26. I can easily buy posters, postcards, picture books, greeting cards, dolls, toys, and children’s magazines featuring people of my race.

All of these have to do with finding proper representation of your race. This is something that white people don’t really have to worry or think about as much. We’ve seen it year after year at the Oscars, nominee lists full of white actors and directors. The lack of people of color on these lists has nothing to do with their merit or the quality of their work. It doesn’t have to do with box office numbers or how the audience or critics respond to it. This problem is ingrained into the whiteness of the Academy, and until they open up a space for diversity and inclusivity, the situation won’t ever truly change.

Dyer, Richard. “On the Matter of Whiteness.” Only Skin Deep: Changing Visions of the American Self, by Brian Wallis and Coco Fusco, International Center of Photography, 2003, pp. 301–311.

Ferrari, Alex. “Are the Oscars Too White...Again? #OscarsSoWhite.” Indie Film Hustle®, 26 Dec. 2019, indiefilmhustle.com/oscars-so-white-oscarssowhite/.

Johnson, Zenzele. “#OscarsSoWhite: Why Representation Matters.” The LAMP, 20 July 2016, thelamp.org/oscarssowhite-why-multi-dimensional-representation-matters/.

Jurgensen, John. “'Parasite' Makes History at the Oscars.” The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 10 Feb. 2020, www.wsj.com/articles/the-stars-are-out-as-the-2020-oscars-kick-off-11581296482.

Mcintosh, Peggy. “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack (1989) .” On Privilege, Fraudulence, and Teaching As Learning, 2019, pp. 29–34., doi:10.4324/9781351133791-4.

Reality Check Team. “Oscars 2020: How Diverse Are the Oscars?” BBC News, BBC, 10 Feb. 2020, www.bbc.com/news/51094069.

Reign, April. “#OscarsSoWhite Creator: With a Mostly White Academy, What Could We Expect? (Column).” Variety, Variety, 15 Jan. 2020, variety.com/2020/film/news/oscarssowhite-nominations-diversity-april-reign-1203467389/.

Reign, April. “OscarsSoWhite Is Still Relevant This Year.” Vanity Fair, Vanity Fair, 1 Mar. 2018, www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2018/03/oscarssowhite-is-still-relevant-this-year.

Ugwu, Reggie. “The Hashtag That Changed the Oscars: An Oral History.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 6 Feb. 2020, www.nytimes.com/2020/02/06/movies/oscarssowhite-history.html.

0 notes