Anthony Orlando, Martha Rivera, Courtney King, Alex Powers

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Traditional Tobacco Use By Alex Powers

youtube

This examination will focus on Mayan utilization of the Chili Pepper. The Aztec empire regarded the Mayans the same way in which we regard the Roman Empire; with this influence, it is natural to assume that many cultural implementations of tobacco were inherited by the Aztecs from the Mayans. The significance of the tobacco plant to Native populations of South and Central America predates the arrival of Spanish and Portuguese explorers to the New World. While not much is known on the official history of Mayan tobacco use, modern narratives would argue that its history could be indirectly observed in the Aztec and Incan interactions with conquistadors. The symbolism of foods like the chili pepper held great importance, like that of tobacco, to many pre-colonial societies of Mesa-America. Implemented in religious ceremonies for the healing properties of the capsicum, and mixed into drinks that also contained cocoa, indigenous use of the Chili Pepper was diversified. Researchers looking into the origins of pots discovered throughout various sites in Southern-Central America discovered, “While our findings of Capsicum species in these Preclassic pots provides the earliest evidence of chili consumption in well-dated Mesoamerican archaeological contexts, we believe our scientific study opens the door for further collaborative research into how the pepper may have been used either from a culinary, pharmaceutical, or ritual perspective during the last few centuries before the time of Christ.“

Foster, Lynne V. Handbook to Life in the Ancient Maya World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Houston, Stephen, John Robertson, and David Stuart. "The Language of Classic Maya Inscriptions.” Current Anthropology 41, no. 3 (2000) pp. 321-56

Thornton, John K. A Cultural History of the Atlantic World. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Terry G. Powis, Emiliano Gallaga Murrieta, Richard Lesure, Roberto Lopez Bravo, Louis Grivetti, Heidi Kucera, Nilesh W. Gaikwad. Prehispanic Use of Chili Peppers in Chiapas, Mexico. PLoS ONE, 2013; 8 (11): e79013 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079013

0 notes

Text

Blog #4

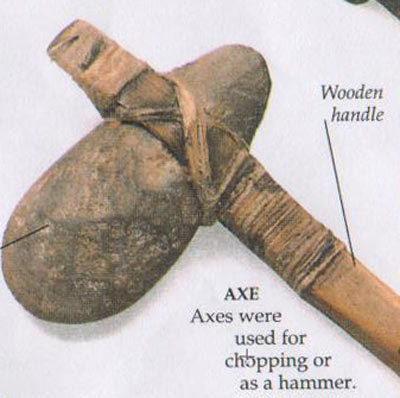

Mayan Farming tools

By Martha Rivera

The Mayans were amazing at being able to make things, especially when it came to feeding their families, as well as, their villages. Mayans didn’t have metal tools for farming so they had to make their own out of certain types of stones, just to name a few (limestone, granite and quartzite) and wood (sapodilla and breadnut). Just to name a few tools that were made by the Mayans were; scrapers, hammers, axes, which they made out of stones and the wood so that they were able to farm with them. Many of their tools for farming were also made of obsidian, a natural resource, which was a type of volcanic glass that was found around volcanos after eruption and found to be useful by the Mayans. Obsidian, was very important to the Mayans, it was used to make a majority of the Mayans tools for farming, but also used in their everyday lives, and to make weapons, which Mayans needed at all times.

http://www.maya-archaeology.org/Mayan_anthropology_ethnography_archaeology_art_history_iconography_epigraphy/minerals_obsidian_artifacts_Belize_Mexico_Guatemala_Honduras.php

Mayan tools. (n.d.). https://aztecandmayan.weebly.com/mayan-tools.html

Learn, J. R. (2016, August 24). Ancient Maya Bloodletting Tools or Common Kitchen Knives? How Archaeologists Tell the Difference. From https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/ancient-maya-bloodletting-tools-or-kitchen-knives-how-archaeologists-tell-difference-1-180960232/

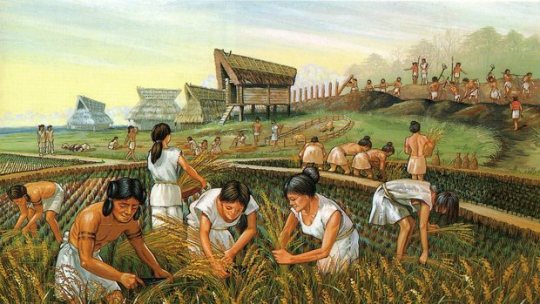

Mayan Agriculture

By Martha Rivera

The quality of agricultural land around Mayan villages depended on their locations. The Mayans dealt with many recurring droughts and rising sea levels, as well as, either rough, rocky terrain intermixed with vast swamps, lowlands or wetlands. How they accomplished to feed their entire villages farming on these lands like this, no one knows, but it was accomplished somehow!

In the lowlands of certain Mayan villages, the soil was relatively fertile but restricted to small patches at times. A technique to increase soil fertility was the use of raised fields, especially near flood areas. They built stone walls to collect fertile deposits throughout their villages. Mayans without access to a larger area of land suitable for agriculture would have to trade with places nearby so that they were able to have the right land for their villages and immediate family to farm on. Some example of items that the Mayans traded were, salt, honey and valuable goods such as metals, feathers, weapons, tools and shells that had to be often traded for plant products and land. Mayans also grew their own little private gardens for their own individual households.

Water was another huge need in their daily lives and their agriculture. In some Mayan villages, during the dry winters and hot summers, water was collected in sinkholes that were created by caves that ended up sinking called tz'onot. Also, Cisterns, which was a tank that stores water and built around the entrance so that it could maximize the collection of rainwater so that they could save it for future uses when the weather changed.

Maya Food & Agriculture. (n.d.) https://www.ancient.eu/article/802/maya-food--agriculture/

“Maya Agricultural Methods.” History, 25 May 2017, www.historyonthenet.com/maya-agricultural-methods/.

Rath, Therese. “Agriculture.” National Institute of Culture and History, www.nichbelize.org/ia-archaeology/agriculture.html.

Mayan Chili Peppers

By Alex Powers

This examination will focus on Mayan utilization of the Chili Pepper. The Aztec empire regarded the Mayans the same way in which we regard the Roman Empire; with this influence, it is natural to assume that many cultural implementations of tobacco were inherited by the Aztecs from the Mayans. The significance of the tobacco plant to Native populations of South and Central America predates the arrival of Spanish and Portuguese explorers to the New World. While not much is known on the official history of Mayan tobacco use, modern narratives would argue that its history could be indirectly observed in the Aztec and Incan interactions with conquistadors. The symbolism of foods like the chili pepper held great importance, like that of tobacco, to many pre-colonial societies of MesoAmerica. Implemented in religious ceremonies for the healing properties of the capsicum, and mixed into drinks that also contained cocoa, indigenous use of the Chili Pepper was diversified. Researchers looking into the origins of pots discovered throughout various sites in Southern-Central America discovered, “While our findings of Capsicum species in these Preclassic pots provides the earliest evidence of chili consumption in well-dated Mesoamerican archaeological contexts, we believe our scientific study opens the door for further collaborative research into how the pepper may have been used either from a culinary, pharmaceutical, or ritual perspective during the last few centuries before the time of Christ."

Foster, Lynne V. Handbook to Life in the Ancient Maya World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Houston, Stephen, John Robertson, and David Stuart. "The Language of Classic Maya Inscriptions." Current Anthropology 41, no. 3 (2000) pp. 321-56

Thornton, John K. A Cultural History of the Atlantic World. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Terry G. Powis, Emiliano Gallaga Murrieta, Richard Lesure, Roberto Lopez Bravo, Louis Grivetti, Heidi Kucera, Nilesh W. Gaikwad. Prehispanic Use of Chili Peppers in Chiapas, Mexico. PLoS ONE, 2013; 8 (11): e79013 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079013

Mayan Foods We Still Consume Today

By Courtney King

What the Mayans grew and farmed back when they were first established and what they farm today has barely changed. They are still consuming what they have for the past hundreds of years and now these foods are eaten across the entire world. It just goes to show that foods the Mayans cultivated so long ago are still being eaten today. Chocolate is a sweet that is consumed all around the world. You can eat chocolate in many different ways, one of those ways being in beverage form - hot chocolate! The Mayans were the first people to take the seeds of the cacao fruit and roast them to make hot chocolate. I find it so amazing that we still drink hot chocolate today but with so many more ingredients and variations. Other delicious foods that are popular today in America and in other places on the globe are avocados and guacamole. Avocados were a treasured crop of the Mayans and people from the area of Antigua Guatemala are sometimes referred to as “green belly�� because they relied so hard on avocados to get them through poor times when there was nothing else to be eaten. Other staple foods such as corn tortillas, corn, salsa, and coffee were also farmed and consumed by the Mayans and are still very popular today in many places. I find it so interesting that these foods started here with the Mayan people - I did not know that until researching more on the subject. It just goes to show that because of trade and other things, people from all over the world can adapt other cultures and the food that comes along with it! In the end, location does not matter a whole lot once trade and other similar climate conditions exist. You can make these foods just about anywhere with good farming practices and the right conditions.

“Top 10 Foods of the Maya World.” National Geographic, 12 Sept. 2012, www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/top-10/maya-foods/.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Blog #3

Vanilla in the Mayan World

By Anthony Orlando

Likely first cultivated by the neighboring Totonac people, the Mayans would use the world’s only edible orchid to flavor their more well-known cocoa drinks (Delsol). Vanilla, along with cocoa and annatto, would in many ways serve as a stabilizing force in the economy of later Mayan states (Marty), particularly Itza until their decline in 1697.

Itza’s farming of vanilla and cocoa during the periods of conflict brought to the region by the Spanish only produced of the resource for its small elite class due to the difficulty in growing the plants in their homeland of central Peten (Marty). Itza would be able to grow in power by seizing more usable land for vanilla growth from neighboring states, giving itself a solid regional and economic base by doing so, while also using their newfound power to subjugate the Manche C’hol Mayans and force them to further trade their vanilla commodities with them (Marty). Spaniards and Portuguese would begin bringing it back to the old world in the 16th century, when they would give vanilla its now used name, meaning “little pod” (Delsol).

Delsol, Christine. “10 Maya Foods That Changed the World's Eating Habits.” SFGate, Hearst Communications, 26 Aug. 2009, www.sfgate.com/mexico/mexicomix/article/10-Maya-foods-that-changed-the-world-s-eating-2477935.php.

Marty. “The History of Vanilla in Ancient Maya Culture.” Ambergris Caye Belize Message Board, Casado Internet Group, 24 Feb. 2017, ambergriscaye.com/forum/ubbthreads.php/topics/521935.html.

How Climate Change Affects Mayan Farmers Today

By Courtney King

Today, Mayans are still alive and practicing their farming ways - the same way they have been doing it since the beginning. A farmer from the Yucatan Peninsula, Dionisio Yam Moo, is a Mayan who still practices a farming technique called milpa. Milpa farming is dependent on rain and is when farmers cut down trees and burn the forest, plant crops, and then let the rest of the burnt and bare land regenerate for up to 30 years. Milpa farming allows the farmers in the Yucatan Peninsula to grow wonderful crops, despite having thin soil with a lack of nutrients. With this technique, vegetables like corn, squash, beans, etc. are able to be grown. But in recent years due to climate change, there has been a lack of rainfall in this area. This is bad for farmers like Yam Moo who uses the milpa technique because it is very dependent on rainfall. He would plant his crops, and then for months there would be no rain until it would pour and then flood the field. This ultimately damaged his crops.

In order to fight the climate change, Yam Moo, along with other mayan farmers, have improved the milpa technique. They do not cut down parts of the forest anymore but they still grow many different crops per usual. And because of the unpredictable rain, they have installed an irrigation system which comes from an above the ground rainwater collector. Yam Moo has also found that tilling the soil with compost keeps it healthy and full of nutrients - so cutting down trees for new land won’t be necessary. Milpa has been around for many many centuries and is still used today, only with improvements because of the new climate Mayan farmers are faced with. They are always improving their methods and still producing crops!

Popkin, Gabriel. “Mayans Have Farmed The Same Way For Millennia. Climate Change Means They Can't.” NPR, NPR, 3 Feb. 2017, www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/02/03/510272265/mayans-have-farmed-the-same-way-for-millennia-climate-change-means-they-cant.

Article 8: Native Tobacco (continued)

By Alex Powers

Tobacco use amongst the Mayan civilization itself, is represented today in what remains of their artwork, literature, and architecture. While the language of the Mayan people remains untranslatable, the art work that adorns the walls of ruins, as well as the statues and monuments surrounding these ruins, paint a vivid picture of Mayan culture utilizing tobacco ritualistically, medicinally, and socially. Cultural differences between the Aztecs and the Mayans were referenced as having a relationship similar to that of modern America and the Romans. The Mayan, Aztec relationship was closer in similarity to the Romans and the Greeks, in that the Mayans were the Greeks and the Aztecs were the Romans. Just as the Greeks did, the Mayans constructed monuments to their gods, many of whom were offered tobacco as homage.

First cultivated in agricultural plots surrounding population densities, harvested, dried, then sold, or distributed, tobacco was a crop that provided no sustenance but was highly desirable. The Mayan use of tobacco as hygienic meant using the smoke to “clean” their teeth, Mayans envisioned the cigar as we the toothbrush. Tobacco smoke played a more significant role in Mayan culture than the tobacco leaf itself. In religious ceremonies, utilizing natural tobacco smoke created hallucinating effects, which accompanied medicine men and shamans as visual aids. In these same religious ceremonies, the smoke rising would represent the ascension of ancestors. While implemented in various facets of their society, true knowledge of Mayan tobacco use remains subjective as much of their history with the plant is quite skeptical. Essentially, what we’ve observed about Mayan tobacco use, was observed with the interactions of later cultures and the Spanish explorers. The importance of visual imagery in scholarship surrounding Mayan tobacco use is vital, as much of the Mayan documentation on their use is untranslatable.

Benjamin, Thomas. The Atlantic World in the Age of Empire. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2001.

Foster, Lynne V. Handbook to Life in the Ancient Maya World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Gately, Iain. Tobacco: A Cultural History of How an Exotic Plant Seduced Civilization. New York: Grove Press, 2001.

Thornton, John K. A Cultural History of the Atlantic World. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Robicsek, Francis. Smoking Gods: Tobacco in Maya Art, History, and Religion. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1978.

Rushforth, Brett. Colonial North America and the Atlantic World: A History of Documents. New York: Routeledge, 2008.

The Mayans and the beginning of Chocolate

By Martha Rivera

It is said that Cocoa beans were first discovered by the Mayan people as early as 600 A.D. The Mayans harvested cocoa beans and because they loved chocolate so much, they eventually cleared much of their lands so that they were able to grow their own cocoa trees and start a plantation harvesting cocoa, as well as their original crops. The word chocolate is said to come from the Mayan word xocolatl, which means bitter water. Chocolate was a liquid made from crushed cocoa beans, chili peppers, and water. They learned that the beans inside the cocoa pods could be made by first harvesting the seeds, drying them, roasting them, removing their shells, and then ground them into paste. Most of the same process has not been changed and still used today, especially by living Mayans who still live by their traditional ways of the past. Mayans called cacao, chocolate “food for the gods” and was a treasured Mayan treat, as well as, still is today. Chocolate, then, was associated with people of high status and drank/ate during special occasions such as; religious ceremonies, parties and marriage celebrations. Mayan artifacts have been found to show Kings of the Mayan gods drinking chocolate.

Cacao became so popular, that even Mayan groups living in other areas, such as the Yucatán, where the climate wouldn't support a tropical rainforest, apparently found ways to grow some cacao trees in their fields. The Mayan people also had many trade networks that helped ensure steady supplies of cacao throughout Mesoamerica, even in areas too cool or dry for cacao trees to flourish.

“Cacao: The Mayan.” Ricochet Science, 14 Apr. 2016, ricochetscience.com/cacao-mayan-food-gods/.

“The History of Chocolate.” Chocolate and the Mayans - Chocolate and the Mayans | HowStuffWorks, HowStuffWorks, 18 Nov. 2007, www.howstuffworks.com/history-of-chocolate1.htm.

Cacao in Ancient Maya Religion, www.mexicolore.co.uk/maya/chocolate/cacao-in-ancient-maya-religion.

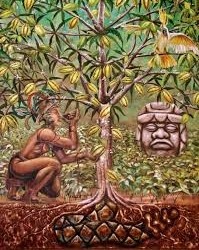

The Maize God

By Courtney King

As you can tell from reading our entries on this blog, agriculture was a major part of the Mayans way of life. Out of all the crops that the Mayans grew, the most important would be the staple crop, corn. Corn or maize was very important to the Mayans because it was easy to grow in their climate, easy to store, and could be served in many different forms and also used for things such as baskets or even fuel - not just solely for being consumed. Because of the importance of corn in the Mayan way of life - there was a God dedicated to this crop. The Maize God, Hun Hunahpu, is depicted as a young man with corn on his headdress and his hair made out of silk from corn. The Maize God was thought to be beheaded at the start of the harvesting season and then reborn once when the new growing season began. Because of this, the Maize God was also looked at as “the cycle of rebirth” and “associated with the growth of crops” - which made this God that much more important. When the Mayans experienced long periods of drought, “...they would turn to the Gods responsible for food, rain and fertility.” (The British Museum). Praying to the Gods gave the Mayans a sense of hope that their crops would be okay and would still prosper. Sometimes, they even had rituals for the Gods that sometimes included sacrificing your own blood or something less serious like singing and dancing. I think it is really cool and interesting how they had so many Gods for various things - even down to corn!

Works Cited: “Teaching History with 100 Objects.” Teaching History with 100 Objects - The Maya Maize God, The British Museum , www.teachinghistory100.org/objects/about_the_object/maize_god.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Blog #2

Mayan Agriculture and Farming Methods

By Martha Rivera

It is believed that the Mayans used a variety of farming methods; terrace farming, a technique using raised field farming and the slash & burn method, which was when they cut down all the trees in a particular area and burn the stumps and trees that were cut down, then, they would use the ashes from that, mix it with soil and plant their seeds for the crops to grow. Only thing with this method was that it would only last for about 3-4 years and the Mayans would then have to pick up and move to another area and start the process over. For them, the use of farming methods depended on the land, as well as, the weather, the weather played a big part. Especially with dry climates, cold winters and droughts. Farming was a way of life for them and also how the Mayans provided for their families and villages. The Mayans depended heavily on farming to get by in the and keep their families fed. Although corn was the Mayans main crop, they also grew beans, squash, cacao, chili peppers and fruit trees, black and red beans were added to their diet for protein, in addition to hunting deer, dog, turkey, rabbit, pigs, birds and fishing to feed their families and provide for their entire village.

“ANCIENT MAYA LIFE.” Ancient Mayan Farming, ancientmayalife.blogspot.com/2012/01/ancient-mayan-farming.html.

“Exhibits on the Plaza.” Civilization.ca - Mystery of the Maya, www.historymuseum.ca/cmc/exhibitions/civil/maya/mmp04eng.shtml.

Mayan Civilization. (n.d.). http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Mayan_Civilization

The Mayans Archives - Page 1 of 3. (n.d.). https://www.historyonthenet.com/category/mayans/page/3/

How Location Affects Agriculture

By Courtney King

Just like anywhere, if you want to grow a crop, you have to make sure that the surrounding lands and soils are fit to grow that specific food. If not, your crop will not grow successfully. The Mayans knew this hundred of years ago when they started farming their most important crops like corn, squash and beans and therefore adjusted the way they farmed to get the best results.

Mayan cities that reside in the lowland areas like Peten and Puuk, had fertile soil but not a lot of it spread across large land plots. So, to increase the soil fertility in more patches of land, the Mayans would use the technique of raised fields. Raised fields were able to drain the land of too much water and improved the soil for the crops. Another technique the Mayans used was planting multiple crops together so they could get the most crops out of the smallest patches of land. They planted beans and squash within the fields of corn, “...so that the beans could climb the maize stalks and the squash could help reduce soil erosion” (Cartwright, 2015). Even though they did not have a lot of land to work with, they still were able to get the most product.

Cities with even less land to farm mostly traded with cities that had a lot of crops or the Mayans themselves had small gardens outside of their homes.

Another aspect about location was that the Mayans experienced hot summers and dry winters, so water management was very important. They used sinkholes that water would be collected in throughout the year and was brought to fields using canals. This way, they always had enough water despite any dry weather.

Even with different climates and weather patterns, the Mayans were still able to farm and grow their crops by creating ways to preserve the soil, save water, and maximize the number of fruits and vegetables that they produce.

Cartwright, Mark. “Maya Food & Agriculture.” Ancient History Encyclopedia, 24 Apr. 2015, www.ancient.eu/article/802/maya-food--agriculture/.

Article 8: Native Tobacco

By Alex Powers

When the Spanish had encountered the Aztec empire, it was long after the Mayan empire had vanished. The Aztec empire regarded the Mayans the same way in which we regard the Roman Empire; with this influence, it is natural to assume that many cultural implementations of tobacco were inherited by the Aztecs from the Mayans. The significance of the tobacco plant to Native populations of South and Central America predates the arrival of Spanish and Portuguese explorers to the New World. While not much is known on the official history of Mayan tobacco use, modern narratives would argue that its history could be indirectly observed in the Aztec and Incan interactions with conquistadors.

Tobacco played an important role in the quotidian life of Aztec, and Incan culture, and the Spanish discovered, “They had touched upon the Atlantic coastline of the Americas in places thousands of miles apart, where they had come into contact with tribes of vastly different cultures and languages who did not know of each other’s existence, and who employed a variety of names for the weed.” (Gately p. 32-33) Each culture utilized tobacco as medicine, a trade commodity, in religious implementations, and recreationally, despite never encountering one another. What modern scholarship knows about Mayan tobacco use comes from Mayan artwork, what remains of Mayan literature addressing the issue remains untranslatable; this presents obstacles for Atlantic historians tracing tobacco’s origins in the Native world. Separation of Mayan, Aztec, and Incan societies resulted in a lack of overt cultural influence, but their coexistence in similar natural environments allowed each to introduce their own understanding of how tobacco should be utilized. (Schlesinger) What did connect these societies was their shared similarities in their utilization of tobacco. By using tobacco as a religious herb, which naturally has hallucinogenic properties, Aztec and Incan societies regarded tobacco smoke as spiritually cleansing; they regarded the herb as medicine for similar reasons. When the Spanish observed tobacco being used in Aztec society, the regarded it as devilish. Seeing Natives smoking, and snorting tobacco was evil; stopping its practice was an important step in the Spanish religious conversion and colonization effort. (Thornton, pp. 54,236)

Benjamin, Thomas. The Atlantic World in the Age of Empire. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2001.

Foster, Lynne V. Handbook to Life in the Ancient Maya World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Gately, Iain. Tobacco: A Cultural History of How an Exotic Plant Seduced Civilization. New York: Grove Press, 2001.

Thornton, John K. A Cultural History of the Atlantic World. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Rushforth, Brett. Colonial North America and the Atlantic World: A History of Documents. New York: Routeledge, 2008.

The Avocado and the Mayans

By Anthony Orlando

Its modern name comedically deriving from the Nahua Aztec word for testicle, “ahuacatl” (Gonzalez), the avocado, originating in the area of what is now Guatemala and southern Mexico, was treasured by the ancient Mayans (Shapiro) much like it it is today by college students and the attendees of business parties (albeit now in the form of guacamole). The mayans themselves would convert wetlands into elaborately irrigated farming zones where the fossilized remains of ancient avocados once harvested there can still be unearthed (Mascarelli), as have been found in modern day Belize. The discovery of the Belize site would also cause some controversy, as the wetlands used for the avocado farming were relatively distant from most major Mayan cities, though physical geographer Timothy Beach has suggested that these wetland farms were supported by relatively large rural populations (Mascarelli).

Citations

Gonzalez, Robbie. “Ahuacatl.” io9, Gizmodo, 4 Nov. 2013, io9.gizmodo.com/the-aztec-word-for-avocado-ahuacatl-means-testicle-1457781245.

Mascarelli, Amanda. “Mayans Converted Wetlands to Farmland.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 5 Nov. 2010, www.nature.com/news/2010/101105/full/news.2010.587.html.

Shapiro, Michael. “Top 10 Foods of the Maya World.” National Geographic, 12 Sept. 2012, www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/top-10/maya-foods/.

Cassava: Fueling an Empire?

By Anthony Orlando

Otherwise known as manioc, tapioca, or yuca, the naturally gluten-free and generally healthy cassava (Mercola) is a tuberous root originating from tropical regions in the America’s (Rodriguez). Cassava also holds “...the highest yield of food energy of any cultivated crop (Carroll)”. In 2007, a 1,400 year old Mayan monocrop farm of cassava was discovered at the archaeological site of Ceren in El Salvador (Drye). Buried in and preserved by 17 ft of ash from a nearby volcanic eruption in 600 AD, the farm site serves as the first solid evidence of widespread cassava consumption in pre-columbian central america (Carroll). The food energy power of the cassava may have not only been able to assist in feeding and sustaining the massive Mayan populace, but also could have also served as the food-fuel for many of the Mayan civilizations architectural wonders (Carroll). Though it is unknown how exactly the ancient Mayans ate it, its versatility likely offered numerous ways, as cassava can be boiled, baked, made into bread (Rodriguez), or even turned into chips (which, from personal experience, are pretty good).

Citations

Carroll, Rory. “1,400-Year-Old Cassava Crop Solves Riddle of the Maya.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 23 Aug. 2007, www.theguardian.com/science/2007/aug/23/1.

Drye, Willie. “Ancient Farm Discovery Yields Clues to Maya Diet.” National Geographic, National Geographic Society, 20 Aug. 2007, news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2007/08/070820-maya-crop.html.

Mercola, Joseph M. “Health Benefits of Cassava.” Mercola.com, 25 July 2016, articles.mercola.com/sites/articles/archive/2016/07/25/cassava-benefits.aspx.

Rodriguez, Hector. “What Is Cassava, and How Can You Eat It?” The Spruce, 20 July 2017, www.thespruce.com/introduction-to-cassava-yuca-2138084.

0 notes

Text

Blog #1

(Anthony Orlando)

Article 1: Mayan Origins

The origin of the Mayan peoples and culture remains relatively vague, though the common consensus seems to be split between the Mayans shooting off from the Olmec or simply migrating to the region/developing into an independent people from indigenous populations (Mott). Takeshi Inomata, a University of Arizona anthropology professor, offered a different narrative in 2013, claiming that the Olmecs and Maya had risen up around the same time and greatly influenced each other’s growth and culture, whilst also claiming that in the pre classical age both groups may have been one in the same, only splitting with the growth of large scale maize based agriculture (Toor) and possible genetic changes within the regions perpetual staple crop (Mott). Earlier claims made in post-contact society regarding the Mayas origin are quite dubious by today’s standards, with propositions ranging from the Lost Tribes of Israel to, as a 16th century Spanish priest would claim, Atlantis (Smith). Regardless, the pre-Mayan peoples that would evolve into them, as well as other groups, would arrive in the Yucatan region at their earliest in 2600 B.C.E (Cóttrill) with the first continuous settlements appearing at the end of the “Archaic Period” in 2000 B.C.E (Smith).

Works Cited:

-Cóttrill, Jaime C. “Mayan Civilization.” Aztec History, 24 Apr. 2017, www.aztec-history.com/mayan-civilization.html.

-Mott, Nicholas. “New Evidence Unearthed for the Origins of the Maya.” National Geographic, National Geographic Society, 26 Apr. 2013, news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/13/130425-maya-origins-olmec-pyramid-ceibal-inomata-archaeology-science/.

-Smith, Herman. “Origin of the Maya…or Where Did Those Dudes Come from Anyway .” San Pedro Sun [San Pedro Town], Edited by Dan Jamison and Eileen Jamison, 9th ed., 19 Aug. 1999, www.sanpedrosun.com/old/99-332.html.

-Toor, Amar. “Origins, Unknown: Where Did the Maya Empire Really Come from?” The Verge, Vox Media, 25 Apr. 2013, www.theverge.com/2013/4/25/4265458/takeshi-inomata-study-proposes-new-theory-on-maya-olmec-origins.

(Martha Rivera)

Article 2: The Pre-Classic Mayan Period

Though many scholars are uncertain when the Mayan Civilization began, it is said to have begun around 2000 B.C. to 1800 B.C., which was considered to be termed the pre classic Mayan period. This was marked as the beginning of evidence that the Mayans had established a new way of life in agriculture, though they still depended heavily on hunting and fishing as their main source of food, they began growing crops such as; corn, beans, squash and cassava, which is known as Yuca to add to their diet. Along with the development of agriculture, basic forms of pottery, stone monument designs with scripts engraved, jade mosaics and carved stone began to appear and these were just the beginning of what the Mayan brought about. Towards the end of the preclassic Maya, the Mayan population began to grow rapidly, religious practices were started and small villages began to develop into cities, with many classes of mayans beginning to dwell, the Mayans started to expand their presence between the high and low land regions. Nakbe in Petén part of Guatemala is the earliest documented city in the Mayan lowlands, where large structures were to be dated back to 750 BC.

Work cited:

B. (n.d.). The Maya. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-worldhistory/chapter/the-maya/

“Pre-classic Period.” Pre-classic Period | MESO-AMERICAN Research Center, www.marc.ucsb.edu/research/maya/ancient-maya-civilization/preclassic-period.

History.com Staff. “Maya.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 2009,

www.history.com/topics/maya.

Maya civilization.

https://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maya_civilization

https://www.penn.museum/documents/publications/expedition/PDFs/54-1/who-were-the-maya.pdf

(Courtney King)

Article 3: Location and Temples

The Mayans resided in what was called Mesoamerica, also known as the lands of Central America and Mexico. More specifically, these indigenous people populated what is modern day Yucatan, Campeche, Quintana Roo, Tabasco, and Chiapas in Mexico. In fact, location influenced these people greatly, considering their name comes from an old city in Yucatan (one of the places they lived) called Mayapan. Location also plays an important role when Mayans were differentiating themselves by their specific location and language. The Mayans called themselves Quiche if they were from the south, or Yucatec if they were from the north. Regardless of which “type” of Mayan they were - they all had one thing in common, building beautiful pyramids that are still standing today. There were lots of these temples spread throughout the lands in which the Mayans lived. There is Lamanai, located in northern Belize, Coba in Mexico, Caracol, which is the largest site in Belize, Tikal, in northern Guatemala, and the most known of them all, Chichen Itza which contains one of the most incredible temples named El Castillo. Those are just a few of the many temples that were spread across Mesoamerica. The main reason for these temple-pyramids were to pay respects to their gods. It is important to note where the Mayans resided because of the fact that Mayans are still alive today and continue the lives their ancestors once lived while getting to see the amazing pyramids that they built so long ago. Another reason why location plays such an important role is because of food and what crops could be grown in a certain area for the Mayans to eat.

Works Cited:

Mark, Joshua J. “Maya Civilization.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 06 Jul 2012. Web. 01 Oct 2017.

History.com Staff. “Maya.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, 2009. Web. 01 Oct. 2017.

Touropia. “10 Most Beautiful Ancient Mayan Temples.” Touropia. N.p., 10 Nov. 2016. Web. 01 Oct. 2017.

Giffen, Mark. “Facts About the Mayan Pyramids.” Synonym. Classroom, n.d. Web. 01 Oct. 2017.

(Alex Powers)

Article 4: Mayan Language(s)

Brown, Cecil H., and Søren Wichmann. “Proto‐Mayan Syllable Nuclei.” International Journal of American Linguistics 70, no. 2 (2004) pp.128-86

Houston, Stephen, John Robertson, and David Stuart. “The Language of Classic Maya Inscriptions.” Current Anthropology 41, no. 3 (2000) pp. 321-56

Thornton, John K. A Cultural History of the Atlantic World. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012. p.324

The language of the Mayans, prior to 2000 B.C., is known as the proto-Mayan language. As the Mayan civilization spread throughout the present day Guatemala regions of Central America during the pre-classic period, the Mayan languages developed alongside. The primary language to emerge from the Mayan classic period, entitled Ch’olan, became the language of elites responsible for diplomatic relations and trade, while local populations continued to speak in variations of the proto-Mayan languages. The survival of the Mayan language into our modern era is largely thanks to the diversification the language experienced in the pre classic period. The Mayan ruling class emphasized the importance of verbal language, as well as the importance of a written text.

(Alex Powers)

Article 5: Mayan Literature & Text

Hamann, Agnieszka1. “Tz’ihb ’write/paint’: Multimodality in Maya glyphic texts.” Visible Language 51, no. 1 (April 2017) pp.38-57

Foster, Lynne V. Handbook to Life in the Ancient Maya World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. p.331

Thornton, John K. A Cultural History of the Atlantic World. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012. p.169

While the majority of common Mayan populations were illiterate, the ruling elite would practice literacy by appointing scribes. While the exact role of the scribe in Mayan society is still contested amongst historians, the belief is that they were the record keepers of the progressing society. The Mayan written language is hieroglyphic; meaning the language utilizes pictures and symbols to represent syllables, as well as logograms to represent entire words. Mayan scribes, or scholars, created many works of art and literature on pottery and in written texts; however, with the arrival of the Spanish, many works of Mayan literature were destroyed in the processes of colonization. Modern historians, examining the few remaining written texts from the Mayan civilizations, are now able to translate more than half of the texts which survived; however, the absence of any sort of reference to the proper utilization of the language leaves much of the remaining documentation untranslatable.

1 note

·

View note