mei | any pronouns | an intj with se grip | ace/aro spec | it's a personal blog yum | main: @meilancholic, art: @tensheeets

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

idk it just feels so good when you realize a fandom friend has become ur friend friend—y’know? like instead of only talking about ur common interest u start branching out and talking to each other about your lives, your other hobbies, and it’s even cooler to remain close if one or both of you lose interest in the fandom you met in. your bond, no longer dependent on the mutual love you had for some thing—now lies upon the kinship you’ve built. i think that’s beautiful

62K notes

·

View notes

Text

tips for your daily routine

1. have rituals to start your day. before sitting down to study, you need to be ready for the day ahead. this could range from watering plants (like you’ve seen in the video hehe) to meditating to cleaning your study space or simply making yourself your cup of coffee

2. if smaller tasks come up, or you really don’t feel like starting: try the 1 minute rule. tell yourself you’ll do the work for just a minute, and if you don’t feel like continuing, you can stop. most often what’s actually holding us back isn’t the task itself but the “starting energy” we need to initiate it.

3. plan study breaks, or use the pomodoro techniques. knowing in advance how much longer you have to study during a session will make you less likely to just pull out your phone now.

4. don’t rely on motivation. you won’t be able to stay motivated for weeks on end, so have a clear plan of tasks you need to get done, regardless of how motivated or inspired you feel that way. cultivating discipline is incredibly important and the sooner you start, the better.

if you want to see what my daily routine/a day in my life in medical school looks like, click here!

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Tumblr Staff: It’s world sleep day!! Go get some sleep!!

People In The Western Hemisphere: It’s like, the afternoon, we have responsibliti-

Tumblr Staff: g̷̡̟̱̋͑͘o̸͔̮̘̫̽ ̴̩̥̈́b̴̀ͅa̴̫̳̍͂̊̈́c̵͖̣̽́̏k̷̟͆̎ ̶̥̲̮̭̎́ţ̶̨̨͔̀̈́ọ̸͍͂̕ ̸̹̥̼͓̑̾b̶̲̮̌͂̌͝ͅe̵̖̔͗̎̓d̴͔͎̺̀̾

24K notes

·

View notes

Photo

inosuke and nezuko being bffs 💕

#TAISHO RUMORS: “Inosuke became very attached to the Nezuko who turned back into a human. Whenever Inosuke did something, he would assume that Nezuko didn’t know or understood, and would first carefully explain to her that this was how it was.”

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

i just want to have someone that can help.

it seems tiring to be the one that’s only capable of helping myself. and believe me, i’m really trying to be better. i am.

i just don’t know anymore. it’s been months and i’m still on a rut.

it’s really difficult to be better.

0 notes

Link

For nearly 20 years, after his first heart attack, I feared losing my dad from a distance, without being able to comfort him or to say to goodbye. And then one day I did.

He died suddenly on a September morning. I flew back to my childhood home that afternoon. He was still there yet gone — his body resting, as they say, or rather, spent. A small crowd of familiar faces hovered as I walked in and hugged him, reaching for what I will always miss most. He was a great hugger. I was too late.

I fell into a pattern in the week that followed. The days were frantic. There were rituals, visits, arrangements to be made, hours of intense sociality and sorrow. The nights were still. When the commotion ceased, I sat at my dad’s desk, opened my laptop, and caught up with work. I found it soothing, as I found getting back to the office soon after. Duties, deadlines, and colleagues simultaneously gave me a break and made me feel my dad’s presence. Work was the place where I had seen him most alive, after all. The place where I could always find him.

I return to those memories often in these days that are so full of loss — of loved ones, of work, of proximity, of a way of life. This year, grief is everywhere, and though it’s been written about and discussed, it’s still going to be felt more acutely at year’s end. Hearing a holiday song, someone told me the other day, brought them to tears. I’m not surprised. “All I want for Christmas is you” takes on a different meaning when you have suffered a loss.

Yes, this year grief is everywhere, but we have nowhere to mourn, except online. With social and working lives going virtual many have lost access to familiar customs, gatherings, and routines that used to comfort the bereft. Those combined losses can put us at risk, and they require managing. A different kind of managing than that we have long been accustomed to.

Complicated Grief

Grief is the personal experience of loss. Mourning is the process through which, with help from others, we learn to face loss, muddle through it, and slowly return to life. Last year, after reading her poignant book Grief Works, I interviewed British psychotherapist Julia Samuel for a piece I wrote with Oxford professor Sally Maitlis about mourning in the office. Samuel had impressed upon me “how physical the experience of loss really is.” Grieving is something we do with our bodies and with each other. It takes stamina and space.

She had also stressed that, for many people, as was true for me, working — and the workplace — can be one of those spaces that help with mourning. Work can offer a sense of stability and predictability, the office some comfort and respite. Routine is soothing. Caring coworkers, at times, can be as valuable and less demanding than family. We hug colleagues who have lost a loved one; our team sits together when facing the loss of one of its own; or we just work quietly next to others and get a reprieve from grieving.

So what happens now that we are besieged by grief while we work and live at a distance for many, many months? “A lot of grief will remain frozen,” Samuel told me recently, “because many people won’t have enough support, enough ritual, to grieve.” Those are circumstances in which the normal and healthy experience of grieving can take a debilitating turn known as “complicated grief.” The term refers to the persistence of acute pain, apathy, and disorientation long after a loss. Reports of exhaustion, angst, and numbness are now beginning to emerge in the workplace. Those experiences are often understood as symptoms of burnout after a burst of panicked productivity earlier in a nine-month-old crisis. But in a year of many losses and much distance, those experiences might well be expressions of a collective bout of complicated grief.

Even those of us who embrace virtual work, I suspect, are struggling with virtual mourning. Recently, for example, I learned that LinkedIn data revealed a change of mores. In 2020, people have been discussing being bereft with their networks in far greater numbers. Those virtual exchanges might be touching, so to speak, but they don’t quite work like actual touch, according to Bill Cornell, an American psychotherapist and author who specializes on the embodied nature of relationships and losses. Cornell advocates using the word remote rather than virtual work to remind ourselves that working this way involves a loss too, that of physical proximity.

Once we acknowledge our remoteness, we can try to understand its impact, Cornell argues. The fatigue that we feel after a video conference, for example, might stem from the fact that each Zoom meeting subtly reminds us that even if our colleagues are very much alive, there are ways that we have lost each other, too. In the same spirit, Samuel reminded me that losing the camaraderie and routines of office life does not end our relationships with work and coworkers. But finding new ways to muster presence, patience, and support requires making room for loss.

How to Make Room For Loss

Many losses cannot be undone, but spaces for mourning those losses can be rebuilt at work. And managers are best positioned to do that. Those who can hold people through loss, whether it involves death or work or proximity, will help them stay healthy, loyal, and productive.

This is how to go about it.

First, acknowledge that people will be anxious, vulnerable, and disoriented — and so are you. Don’t just pretend that things are normal: Share your experience, invite people to share theirs, and make that behavior normal. Even just sharing what you miss most of your old working days at the office, and how you are struggling to learn how to deal with it, might be liberating.

Second, right after sympathy, offer truth. Here is the data. Here is what we are dealing with right now. Take questions. It will soothe people’s anxiety to be heard, even if you don’t have answers to their queries. If it is hard to make long-term predictions, better not make any. Sharing your company monthly revenues and your plans to deal with a steep drop, for example, will be more honest and useful than giving people a pep talk about how bright the next quarter will be.

Third, simplify the work. Make it more manageable. When we are anxious and remote, it helps to focus on clear and concrete goals, to know what is expected and what is enough. Such clarity is ever more important as people return to the office, but not to old normality. Knowing where, when, and how long people are expected to work, for example, is grounding. Grief hijacks the imagination, filling it with catastrophic projections. Just like mourners can find some comfort focusing on their breath, a meal, or regular exercise, there is value in manageable work. Grief erases our sense of agency, and work can help restore it. “Having a task that you can complete when you feel powerless is very helpful,” Samuel advises.

All of these actions help to ground your colleagues in reality and orient them to the present. That is the best work can offer: Reminding us that we are here for now. We often tell those who manage and lead to portray confidence, spark the imagination, and focus on the future. That future orientation is “all well and good,” Cornell cautions, “but it’s difficult when you are sitting with people who have no idea what next week will be like, let alone the future.”

I do not mean to say, with all this, that we need to just get on with an ill-defined “new normal.” That would be like telling those who have lost a loved one that they “will get over it.” We never do. But staying in the present, focusing on the reality of uncertainty and remoteness, can keep us going and connected as we learn to live with loss and maybe, slowly, grow through it.

For managers to make room for loss, however, they must brave a loss of their own: of principles and prescriptions that have long oriented them. By turning from the future to the present, from a sparked imagination to a held heart, from confidence to care, a manager can help us regain our footing and, slowly, some hope. Letting those old prescriptions go, I have written before, might help us humanize management. Likewise, these months in which we have lost each other might end up humanizing work. If it reminds us that we need space to share and soothe our grief, remoteness might even bring us closer. That might be a hopeful ending for a year of loss.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to write about Grief:

There is no right or wrong way to experience grief. Just as there is no right or wrong way to write it. Everyone is different, each set of circumstances are different.

The point of this post is to show you how different people react in different ways, and give points on how you might write that, depending on your character and story.

Reactions to Grief

Numbness: Your character may go into auto-pilot and be unable to process the events that have unfolded.

Anger: This can be aimed at other people, at a Higher Being, or at nothing in particular.

Unsteady: Your characters may be unsteady. For example, unable to stop their voice from shaking or they may find it difficult to stand.

Focusing on Others: Your character may disregard their own feelings because they are so overwhelmed and instead concentrate on someone else’s well-being.

Seek out routines: Amid upheavals, your character may seek comfort in tasks that are familiar and “safe,” such as working, cleaning, making their bed, making absurd amounts of tea or taking a morning walk.

Pretending that Everything Is Okay: Grief is viewed as an emotion that should cease or be concealed once the funeral is over. So people mention the news in an offhand comment, then talk and laugh as if all is right with the world.

Denial: Some people deny the reality of death and convince themselves that the news is a joke or can’t be true.

Reactions from people surrounding your character:

People may avoid your character as they do not know what to say or simply can’t find the right words.

Some may even go as far as to cross the street when they notice your character approaching.

Even people that the character has known for years may act strange or standoff-ish, simply because they don’t know what to say.

On the other side of that, some people may be overly helpful and friendly.

It is not uncommon for estranged friends, family or others to suddenly reappear in a person’s life after they have experienced grief.

Either because those people want to offer their support and love or because they’re being nosy and they want to be kept up to date on the “drama”.

Most people will move on from the event fairly quickly if they weren’t emotionally invested.

Some people may even get annoyed at your character for still being upset weeks or months later.

When talking about the person they have lost:

Your character may recall a memory or tell a story about their loved one, these are possible reactions. (I have encountered all of them.)

Your character may being to cry or get upset at the thought of the person they have lost.

The person they are talking to may become awkward and avert eye contact when your character brings up the person they have lost.

Others may ask or tell your character to stop talking about the person they have lost. They may roll their eyes, cough awkwardly, or cut off your character mid sentences so that they can change the subject.

Some people may ask inappropriate questions about the circumstances in which the character’s loved one passed away. Depending on the personality of your character then may react differently.

Other things to note:

Grief is not constrained by time.

One of the main problems with grief in fiction is that a character is typically heartbroken for a couple scenes and then happy again. But grief does not evaporate because the world needs saving.

Allow your character to wrestle with their grief.

Your character may feel guilty. Your character may feel a twinge of guilt when they laugh or have a good time with someone else; when they do something to remind them that they’re alive, and their loved one isn’t.

Grief is a game changer. A previously outgoing character may withdraw and isolate themselves. Some people may take grief and/or bereavement as a sign that life is too short; they may make big decisions in an attempt to make themselves feel better and grow away from their pain.

Sometimes grief can help you find your purpose.

At first grief can be all consuming. It hurts and you can’t really control it. It may seem unrelenting. Eventually the grief will become easier to deal with, your character may find the days to be better, but that doesn’t mean that when the grief hits it doesn’t hurt any less.

For most people, grief never really goes away. “Sometimes you have to accept the fact that certain things will never go back to how they used to be.”

It is rare that a person will ever give a long speech about their feelings, a lot of people struggle to even find the words. But that’s okay. Show the reader how your character feels, rather than just telling them.

Don’t pause the plot to deal with the aspect of grief. This could overwhelm the readers and drag the pace down. In reality, life doesn’t just stop due to grief, the world keeps spinning and things still need to be done. Use the character’s grief as a backdrop for the story’s events.

Yes, grief affects the character’s day-to-day life, goals, and relationships. But it shouldn’t drive readers away or stagnate the story. Instead, should engage readers and produce empathy that keeps them turning pages.

You don’t need to tell your readers that everything will be fine. You don’t need to provide all of the answers.

“Skirting grief and treating it lightly is easy. But by realistically portraying it through a variety of responses and its lasting effects on the character’s life, readers will form a connection with your characters.“

26K notes

·

View notes

Text

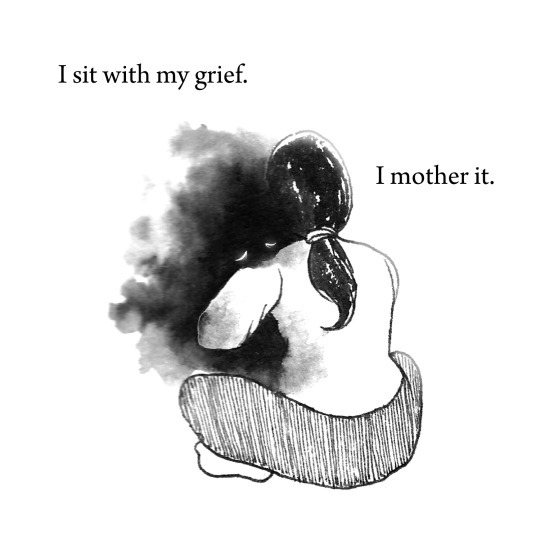

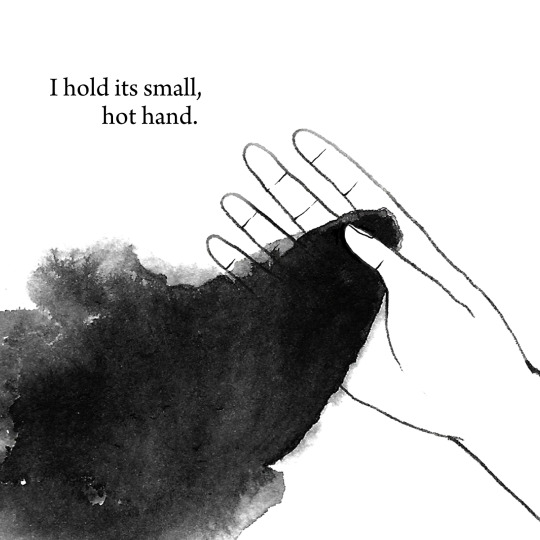

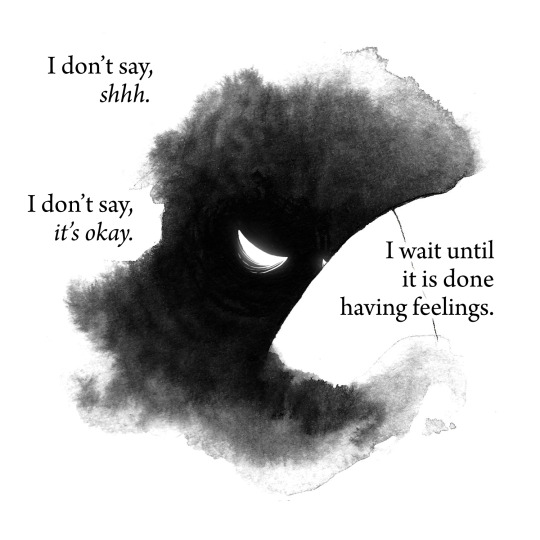

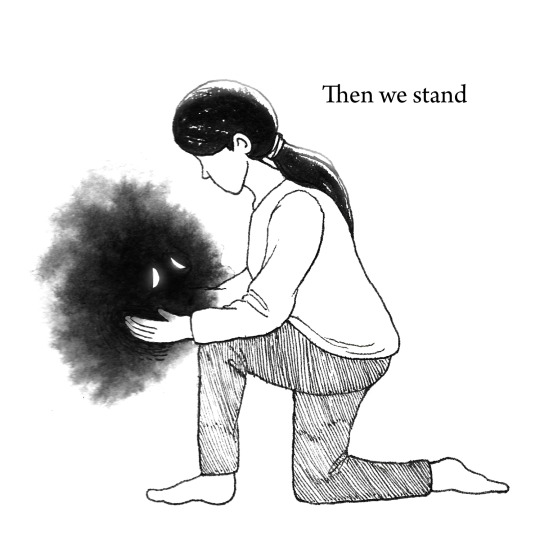

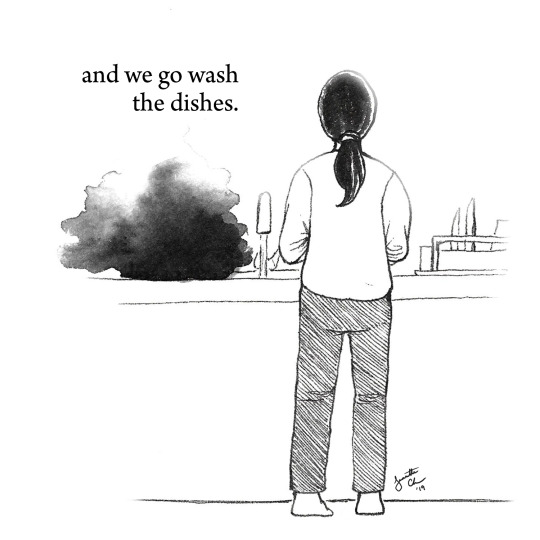

I sit with my grief. I mother it. I hold its small, hot hand. I don’t say, shhh. I don’t say, it's okay. I wait until it is done having feelings. Then we stand and we go wash the dishes.

-- Callista Buchen, from Taking Care

113K notes

·

View notes

Text

miranda july / don delillo / holly warburton / richard siken / aaron diaz / ross gay / robert anton wilson / david foster wallace

24K notes

·

View notes

Text

me: trying to get my shit together and do some work

my brain: how can you be calm and work when NOBODY EVER LOVED YOU

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

the body of a stranger

the teeth in my mouth are already rotting

so why should i care

whether they heal or crumble

the brain in my skull is already rotting

so why should i care

whether to stay sane or to decay

my muscles are aching

and my stomach hurts

i know this body shouldn’t be mine

and yet

i sit here

thinking

about all things i hate about having a vessel

that looks like this

that speaks like this

that feels like this

that aches like this

and knowing that this will not change any time soon

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

one day ure 22 then the next ure 23. sick. twisted. dark sided. limp wristed.

55K notes

·

View notes