[31, she/her] Studying: Gàidhlig (I post about other languages too!)

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Video

youtube

「私のお気に入り」

歌詞

バラの雫に子猫の髭 磨いたケトルにふんわりミトン ちょうちょ結びの贈り物 みんな大好きmy favorite things

クリーム色の子馬にアップルタルト そりの鈴に美味しいヌードル 月の谷間飛ぶ鳥 みんな大好きmy favorite things

真っ白いドレスにブルーのベルト まつげにほら 積もる雪 春が来たなら溶ける冬 みんな大好きmy favorite things

驚いて悲しくて泣きたいなら 思い出しましょmy favorite things これで私オーケ

Winter Songbook on iTunes

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

34K notes

·

View notes

Text

English is weird

John McWhorter, The Week, December 20, 2015

English speakers know that their language is odd. So do nonspeakers saddled with learning it. The oddity that we all perceive most readily is its spelling, which is indeed a nightmare. In countries where English isn’t spoken, there is no such thing as a spelling bee. For a normal language, spelling at least pretends a basic correspondence to the way people pronounce the words. But English is not normal.

Even in its spoken form, English is weird. It’s weird in ways that are easy to miss, especially since Anglophones in the United States and Britain are not exactly rabid to learn other languages. Our monolingual tendency leaves us like the proverbial fish not knowing that it is wet. Our language feels “normal” only until you get a sense of what normal really is.

There is no other language, for example, that is close enough to English that we can get about half of what people are saying without training and the rest with only modest effort. German and Dutch are like that, as are Spanish and Portuguese, or Thai and Lao. The closest an Anglophone can get is with the obscure Northern European language called Frisian. If you know that tsiis is cheese and Frysk is Frisian, then it isn’t hard to figure out what this means: Brea, bûter, en griene tsiis is goed Ingelsk en goed Frysk. But that sentence is a cooked one, and overall, we tend to find Frisian more like German, which it is.

We think it’s a nuisance that so many European languages assign gender to nouns for no reason, with French having female moons and male boats and such. But actually, it’s we who are odd: Almost all European languages belong to one family–Indo-European–and of all of them, English is the only one that doesn’t assign genders.

More weirdness? OK. There is exactly one language on Earth whose present tense requires a special ending only in the third-person singular. I’m writing in it. I talk, you talk, he/she talks–why? The present-tense verbs of a normal language have either no endings or a bunch of different ones (Spanish: hablo, hablas, habla). And try naming another language where you have to slip do into sentences to negate or question something. Do you find that difficult?

Why is our language so eccentric? Just what is this thing we’re speaking, and what happened to make it this way?

English started out as, essentially, a kind of German. Old English is so unlike the modern version that it’s a stretch to think of them as the same language. Hwæt, we gardena in geardagum þeodcyninga þrym gefrunon–does that really mean “So, we Spear-Danes have heard of the tribe-kings’ glory in days of yore”? Icelanders can still read similar stories written in the Old Norse ancestor of their language 1,000 years ago, and yet, to the untrained English-speaker’s eye, Beowulf might as well be in Turkish.

The first thing that got us from there to here was the fact that when the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes (and also Frisians) brought Germanic speech to England, the island was already inhabited by people who spoke Celtic languages–today represented by Welsh and Irish, and Breton across the Channel in France. The Celts were subjugated but survived, and since there were only about 250,000 Germanic invaders, very quickly most of the people speaking Old English were Celts.

Crucially, their own Celtic was quite unlike English. For one thing, the verb came first (came first the verb). Also, they had an odd construction with the verb do: They used it to form a question, to make a sentence negative, and even just as a kind of seasoning before any verb. Do you walk? I do not walk. I do walk. That looks familiar now because the Celts started doing it in their rendition of English. But before that, such sentences would have seemed bizarre to an English speaker–as they would today in just about any language other than our own and the surviving Celtic ones.

At this date there is no documented language on Earth beyond Celtic and English that uses do in just this way. Thus English’s weirdness began with its transformation in the mouths of people more at home with vastly different tongues. We’re still talking like them, and in ways we’d never think of. When saying “eeny, meeny, miny, moe,” have you ever felt like you were kind of counting? Well, you are–in Celtic numbers, chewed up over time but recognizably descended from the ones rural Britishers used when counting animals and playing games. “Hickory, dickory, dock”–what in the world do those words mean? Well, here’s a clue: hovera, dovera, dick were eight, nine, and ten in that same Celtic counting list.

The second thing that happened was that yet more Germanic-speakers came across the sea meaning business. This wave began in the 9th century, and this time the invaders were speaking another Germanic offshoot, Old Norse. But they didn’t impose their language. Instead, they married local women and switched to English. However, they were adults and, as a rule, adults don’t pick up new languages easily, especially not in oral societies. There was no such thing as school, and no media. Learning a new language meant listening hard and trying your best.

As long as the invaders got their meaning across, that was fine. But you can do that with a highly approximate rendition of a language–the legibility of the Frisian sentence you just read proves as much. So the Scandinavians did more or less what we would expect: They spoke bad Old English. Their kids heard as much of that as they did real Old English. Life went on, and pretty soon their bad Old English was real English, and here we are today: The Norse made English easier.

I should make a qualification here. In linguistics circles it’s risky to call one language easier than another one. But some languages plainly jangle with more bells and whistles than others. If someone were told he had a year to get as good at either Russian or Hebrew as possible, and would lose a fingernail for every mistake he made during a three-minute test of his competence, only the masochist would choose Russian–unless he already happened to speak a language related to it. In that sense, English is “easier” than other Germanic languages, and it’s because of those Vikings.

Old English had the crazy genders we would expect of a good European language–but the Scandinavians didn’t bother with those, and so now we have none. What’s more, the Vikings mastered only that one shred of a once lovely conjugation system: Hence the lonely third-person singular -s, hanging on like a dead bug on a windshield. Here and in other ways, they smoothed out the hard stuff.

They also left their mark on English grammar. Blissfully, it is becoming rare to be taught that it is wrong to say Which town do you come from?–ending with the preposition instead of laboriously squeezing it before the wh-word to make From which town do you come? In English, sentences with “dangling prepositions” are perfectly natural and clear and harm no one. Yet there is a wet-fish issue with them, too: Normal languages don’t dangle prepositions in this way. Every now and then a language allows it: an indigenous one in Mexico, another in Liberia. But that’s it. Overall, it’s an oddity. Yet, wouldn’t you know, it’s a construction that Old Norse also happened to permit (and that modern Danish retains).

We can display all these bizarre Norse influences in a single sentence. Say That’s the man you walk in with, and it’s odd because (1) the has no specifically masculine form to match man, (2) there’s no ending on walk, and (3) you don’t say in with whom you walk. All that strangeness is because of what Scandinavian Vikings did to good old English back in the day.

Finally, as if all this weren’t enough, English got hit by a fire-hose spray of words from yet more languages. After the Norse came the French. The Normans–descended from the same Vikings, as it happens–conquered England and ruled for several centuries, and before long, English had picked up 10,000 new words. Then, starting in the 16th century, educated Anglophones began to develop English as a vehicle for sophisticated writing, and it became fashionable to cherry-pick words from Latin to lend the language a more elevated tone.

It was thanks to this influx from French and Latin (it’s often hard to tell which was the original source of a given word) that English acquired the likes of crucified, fundamental, definition, and conclusion. These words feel sufficiently English to us today, but when they were new, many persons of letters in the 1500s (and beyond) considered them irritatingly pretentious and intrusive, as indeed they would have found the phrase “irritatingly pretentious and intrusive.” There were even writerly sorts who proposed native English replacements for those lofty Latinates, and it’s hard not to yearn for some of these: In place of crucified, fundamental, definition, and conclusion, how about crossed, groundwrought, saywhat, and endsay?

But language tends not to do what we want it to. The die was cast: English had thousands of new words competing with native English words for the same things. One result was triplets allowing us to express ideas with varying degrees of formality. Help is English, aid is French, assist is Latin. Or, kingly is English, royal is French, regal is Latin–note how one imagines posture improving with each level: Kingly sounds almost mocking, regal is straight-backed like a throne, royal is somewhere in the middle, a worthy but fallible monarch.

Then there are doublets, less dramatic than triplets but fun nevertheless, such as the English/French pairs begin/commence and want/desire. Especially noteworthy here are the culinary transformations: We kill a cow or a pig (English) to yield beef or pork (French). Why? Well, generally in Norman England, English-speaking laborers did the slaughtering for moneyed French speakers at the table. The different ways of referring to meat depended on one’s place in the scheme of things, and those class distinctions have carried down to us in discreet form today.

The multiple influxes of foreign vocabulary partly explain the striking fact that English words can trace to so many different sources–often several within the same sentence. The very idea of etymology being a polyglot smorgasbord, each word a fascinating story of migration and exchange, seems everyday to us. But the roots of a great many languages are much duller. The typical word comes from, well, an earlier version of that same word and there it is. The study of etymology holds little interest for, say, Arabic speakers.

To be fair, mongrel vocabularies are hardly uncommon worldwide, but English’s hybridity is high on the scale compared with most European languages. The previous sentence, for example, is a riot of words from Old English, Old Norse, French, and Latin. Greek is another element: In an alternate universe, we would call photographs “lightwriting.”

Because of this fire-hose spray, we English speakers also have to contend with two different ways of accenting words. Clip on a suffix to the word wonder, and you get wonderful. But–clip an ending to the word modern and the ending pulls the accent along with it: MO-dern, but mo-DERN-ity, not MO-dern-ity. That doesn’t happen with WON-der and WON-der-ful, or CHEER-y and CHEER-i-ly. But it does happen with PER-sonal, person-AL-ity.

What’s the difference? It’s that -ful and -ly are Germanic endings, while -ity came in with French. French and Latin endings pull the accent closer–TEM-pest, tem-PEST-uous–while Germanic ones leave the accent alone. One never notices such a thing, but it’s one way this “simple” language is actually not so.

Thus English is indeed an odd language, and its spelling is only the beginning of it. What English does have on other tongues is that it is deeply peculiar in the structural sense. And it became peculiar because of the slings and arrows–as well as caprices–of outrageous history.

22K notes

·

View notes

Text

Tha mi air bhioran! My husband has just ordered 'Scottish Gaelic in 12 Weeks' for me as a late xmas present! Tha mi cho toilichte!

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

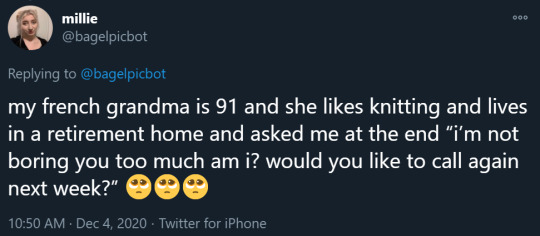

Here is the link! What an amazing idea ❤️

92K notes

·

View notes

Link

“Taibhhsear” (pronounced tive'sher) is the title given to one who can see spirits of the dead - literally ghost seer. Capturing the essence of this spoken word album project.

Scotland has many traditions such as this veiled within Gaelic charms, language and memories shared in metaphor and song.

With your support, we will be able to rediscover, reinvigorate, record and share a collection of these folk magic traditions in Gaelic and English, reclaiming them helping us share the knowledge with you and others.

My friend Scott of The Cailleach’s Herbarium blog is raising money to help share and preserve Scottish folk magic traditions. Please share and donate if you can :)

922 notes

·

View notes

Photo

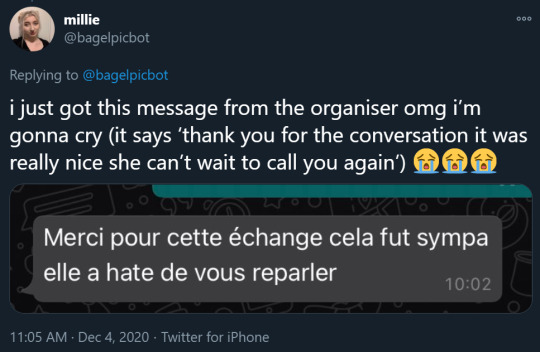

猫飼ってない私でもこれを読んで「分かるぅぅ!」って言い出した、笑

どいてくれないネコ https://twitter.com/kyuryuZ/status/1273812918467887104

141K notes

·

View notes

Text

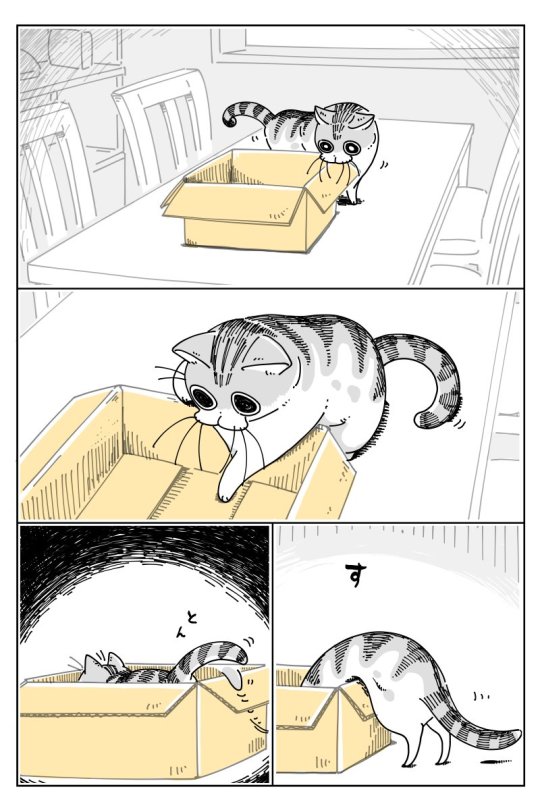

Reading in your target language just got so much easier

This cool little website, called readlang, allows you to upload your book, in your target language, from epub form into their website, right? And you just read your book from there. When you don’t know a word, what do you do? Do you go to google dot com and type in that word? Nope. You fucking click it. And it tells you the word.

I am currently reading the 100 (this is the book that the tv show came from) and I can already tell reading this way is so much easier. I highly suggest making an account. It’s free, and works for more than 80 languages!

40K notes

·

View notes

Text

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Les Gros Mots

Swears in French

swear level 1: Mom uses these (shoot, darn ect.)

zut- Interjection

Zut ! J’ai oublie mes clés ! / Shoot! I forgot my keys!

sacré- adjective (literally means holy) (old fasioned, quaint)

Ce sacré moustique ! / This darn mosquito!

Sacrebleu- literally no one says this

Mon dieu- used like ‘oh my god’ in English

Nom de dieu- used like ‘oh my god’ in English

mince- when used as an adjective it means thin, when used as an interjection in means something like ‘man’ or ‘geez’.

Oh mince, il pleut. / Aw man, it’s raining.

La vache- lit. the cow, used as an interjection kinda like fudge in english

Swear level 2: Can be said in front of mom (damn, shit)

Merde: shit, can be a noun or an interjection

Con- stupid, asshole (can be a noun or an adjective)

Chier: to shit, a verb

Un merdier: a situation that is shit, a mess, a cluster fuck

l’élection de 2016 était un merdier / the 2016 election was a mess

Bon sang: lit. ‘Good blood’. used like holy shit.

Fumier- manure, used like jerk or dick

un fumier un jour, un fumier toujours. / Once a jerk, always a jerk.

Firme ta gueule/ta gueule- Shut up, lit. close your snout.

gueule- used kinda like ‘your ass’ in american english. literally it means mouth, but its usually used for animals so it becomes insulting when applied towards humans.

Je vais casser la gueule ! / I’m gonna kick your ass!

Dégueulasse/dégueu- the vulgar form of gross

j'en ai marre- i’m sick of/fed up with it

Swear level 3: Maybe if you have a cool mom (fuck, ass)

Un merdier: a situation that is shit, a mess, a cluster fuck

l’élection de 2016 était un merdier / the 2016 election was a mess

emerdeur/deuse- shit-stirrer

baiser- used to mean to kiss, now means to fuck or to kiss depending on context

Merdasse- more vulgar form of shit

chiant(e)- so annoying lit. a thing that is shitty

faire des conneries- to fuck up, to do stupid shit

Dégueulasse/dégueu- gross

Bordel- mess, lit. a brothel

Firme ta gueule - Shut up, lit. close your snout.

Connard/connase- bastard, jerk, asshole

Cul- ass (as in the body part)

ça me fait chier- This is boring me to death lit. this makes me shit myself

Abruti(e)- dumb ass

Salaud- (male) jack ass

Salope- dirty woman, whore

Saloper- verb meaning to screw someone over

Saloperie- fuckery, fucked up shit

Putain- Used as often and in about as many ways as we use fuck. Means whore in medieval french.

Putain ! Je me suis cogné le putain d’orteil ! / Fuck! I stubbed my fucking toe!

Pute- the ho’ to putain’s whore, still used like whore/ho

Fils d’un pute- Son of a whore (an insult)

Pétasse- slut

Chienne- bitch (like in english lit female dog)

Garce- bitch (reclaimed by gay guys)

Enfoiré(e)- dumbass lit. having to do with diarrhea

Enflure- douchebag, asshole. lit. swelling

Chatte- Pussy (the body part)

bite- dick (the body part)

Branler- to jerk off

Branleur- wanker

Se Casser- to go fuck off lit. to break yourself

Niquer- to fuck

Nique ta mère- go fuck your mom

Enculer- to fuck up the ass

Combos

[Putain de] + [insult swear]

Putain de salope ! / fucking bitch!

Dégueulasse/dégueu- gross

[bordel de] + [anything you want]

assez avec ce bordel de merde / enough with this fucking shit

For more fun you can stack putain and bordel onto the same word

Putain/enculé(e) de ta race- means something like ‘ you are the worst representative of your type’ (apparently its not racist, but it makes me feel weird)

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

spotted on twitter

Do you know why we don’t pay the water bill in a haunted house?

Because the water ghost will pay

(pronounce this out loud)

7K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Japanese puns are the best

https://twitter.com/s_abao/status/1127583704983805952

918 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Je ne comprends que l’amour et la liberté. // I only understand love and liberty.

-From the original manuscript of Les Misérables by Victor Hugo

#langblr#french#français#languages#language#francais#language study#frenchblr#french langblr#french resources#language learning#french vocab#victor hugo

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

Fantastic French Expressions

This is a list of expressions, phrases, and idioms that are ideal for writing. I got them from my actual whole man, the Collins French Dictionary, which is great for all students, even self-taught ones.

Tout le monde s’accorde à dire que - Everyone agrees that

Il est bien connu que - It is a well-known fact that

Un problème souvent évoqué, c’est - A much-discussed problem is

Cette question est depuis longtemps au cœur du débat sur [topic] - This question has always been at the heart of the debate about [topic] (e.g. gender, education, civil rights, etc)

La première constatation qui s’impose, c’est que - The first point to note is that

Prenons comme point de départ - As a starting point

Il convient maintenant d’analyser - We must now analyse

Il faut nous poser cette question - We must ask ourselves

En somme / En définitive / Au demeurant - In conclusion

D’une part … de même que - On one hand / Likewise

En revanche / Cependant / Par contre / Au contraire - However / On the contrary

À cela s’ajoute / En outre / En addition - Even more / In addition

D’ailleurs - Moreover

Il insiste sur le fait que - He insists on the fact that… et il voudrait nous faire croire que - he would make us believe that

Prenons le cas de - As an example

Il est indéniable que / Il ne fait aucun doute que - It is evident that

La polémique met en lumière - The issue brings to light

Il serait vain de nier que - One can’t deny that

Les faits sont en contradiction avec ses opinions - The facts are in contraction with his opinions

Il était grand temps que + subj - It’s high time that

#langblr#french#français#languages#language#francais#language study#french langblr#frenchblr#french resources

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

♥️French Love Phrases♥️

(Just in case, ya feel me?😏)

Don’t be afraid to ask for any more phrases/vocab 🌸

Tomber amoureuse/amoureux de quelqu’un

To fall in love with someone

Mon chéri/ma chérie

My dear/love (m/f)

Le coup de foudre

Love at first sight

Je t’aime

I love you

Je t’aime aussi

I love you too

Je t’aime plus que tout

I love you more than anything

Tu es incroyable

You are incredible

Tu es jolie/belle

You are pretty/beautiful (f)

Tu es beau

You are beautiful/handsome (m)

Je pense toujours à toi

I’m always thinking about you

Je t’aime de tout mon cœur

I love you with all my heart

Tu es l’homme/la femme de mes rêves

You are the man/woman of my dreams

Je suis amoureuse/amoureux

I am in love (f/m)

Je suis amoureuse/amoureux de lui/elle/eux

I am in love (f/m) with him/her/them

Je suis célibataire

I’m single

(Bonus for the LGBT community 🏳️🌈)

Je suis hétérosexuel(le)

I am straight (m/f)

Je suis homosexuel(le)

I am gay (m/f)

Je suis bisexuel(le)

I am bisexual (m/f)

Je suis transsexuel(le)

I am transgender (m/f)

Quel est ton identité sexuel?

What’s your gender identity?

Quelle est ton orientation sexuel?

What is your sexuality?

#langblr#french#français#languages#language#francais#language study#frenchblr#french langblr#french resources#french vocab#french language#french vocabulary

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Teen French expressions

For if you want to make hip young friends.

Disclaimer: French people complain a lot. A lot. Don’t be surprised if 90% of these expressions are complaining.

Non mais oh - say this if someone does something mildly annoying and you want to express your shock and distaste.

Tu me fais chier - (alt. tu me fais chier, là.) literally ‘you make me shit’. means you’re pissing me off.

Carrément - translates to ‘squarely’. Means ‘literally’. If someone tells you something surprising or annoying, you can answer simply “ah carrément.” see: tu me fais carrément chier.

J’hallucine / je rêve - are you annoyed by something? say these.

C’est pas possible - a classic. anything bad happens - c’est pas possible. There is no cheese left? It’s not possible. I’m hallucinating. This is a burden on me that solely I can bear I cannot believe this is happening.

Ça commence à me gaver - I’m starting to get real sick of this. see: Ça commence carrément a me gaver là, putain.

T’es relou - verlan slang for ‘lourd’ meaning someone’s heavy, personality-wise. They’re tedious.

Ça me saoûle / ça me gonfle - similar to gaver, means something’s pissing you off, you’re sick of it.

Grave - totally.

C’est clair - totally/that’s clear. Like ‘claro’ in spanish. “Justine elle est trop relou” “C’est clair. Elle me fait chier.”

J’en ai marre - I’m sick of this.

J’en ai ras le bol - I’m sick of this.

J’en ai ras le cul - I’m sick of this (vulgar).

(J’en ai) Rien à battre - I don’t give a damn.

(J’en ai) Rien à foutre - I don’t give a fuck.

C’est bon, là. - That’s enough.

Perso, euh, - “Personally,” generally used at the start of a complaining sentence, to express how personal the matter is to you. Perso, euh, c’est bon là. J’en ai ras le cul.

Rôh là - general expression of distaste. Le longer the rôh, the more annoyed you are. Rôôôôôôôôôôôôôôôôôôôôôôôôôôôôh, c’est quoi ce bordel.

C’est quoi ce bordel ? - translates to “what’s this brothel”, means “what’s this shit?!”

C’est de la merde - It’s shit.

C’est une blague ? - Is this a joke?

Idem - ditto

J’ai la dal - I’m hungry

Ça caille - It’s freezing

Ouf - two meanings 1. phew or 2. verlan for “fou”, meaning crazy (as a noun or adjective). “Kévin, c’est un ouf! Il fait du vélo sans casque!” “Ouais carrément, c’était un truc de ouf!”

Kévin - there’s a running joke that all the young delinquents seem to be called Kévin.

Crever - slang for “to die”. Va crever, connard!

Connard/Connasse - c*nt, but a lot less vulgar in french peoples eyes

And finally,

T’es con. No English translation can express the power behind the words “t’es con”. While it may sort of translate to “you’re a c*nt/idiot”, it expresses something much deeper. You really are a god damn fool.

45K notes

·

View notes

Text

Conjugation will be the death of me

Irregular past participles

Acquérir (to acquire) → acquis

Apprendre (to learn) → appris

Atteindre (to attain) → atteint

Asseoir (to sit) → assis

Avoir (to have) → eu

Boire (to drink) → bu

Comprendre (to understand) → compris

Conduire (to drive) → conduit

Connaitre (to know) → connu

Construire (to build) → construit

Courir (to run) → couru

Couvrir (to cover) → couvert

Craindre (to fear) → craint

Croire (to believe) → cru

Décevoir (to deceive; to disappoint) → déçu

Découvrir (to discover) → découvert

Devoir (to have to) → dû

Dire (to say) → dit

Écrire (to write) → écrit

Etre (to be) → été

Faire (to do; to make) → fait

Falloir (to have to) → fallu

Instruire (to instruct) → instruit

Joindre (to join; to affix) → joint

Lire (to read) → lu

Mettre (to put) → mis

Mourir (to die) → mort

Naître (to be born) → né

Obtenir (to obtain) → obtenu

Offrir (to offer) → offert

Ouvrir (to open) → ouvert

Peindre (to paint) → peint

Permettre (to allow; to permit) → permis

Plaire (to please) → plu

Pleuvoir (to rain) → plu

Prendre (to take) → pris

Produire (to produce) → produit

Pouvoir (to be able to) → pu

Recevoir (to receive) → reçu

Réduire (to reduce) → réduit

Rire (to laugh) → ri

Savoir (to know) → su

Souffrir (to suffer) → souffert

Suivre (to follow) → suivi

Tenir (to hold) → tenu

Vivre (to live) → vécu

Valoir (to be worth) → valu

Voir (to see) → vu

Vouloir (to want) → voulu

2K notes

·

View notes