Hi there! Come along with me on my next wonderous adventure....an Aztec adventure in Mexico! This travel log will focus on my personal experiences with the Ancient Aztecs. I got to meet some major historical figures and locals, visit a bustling market, witness some...interesting festivals, and visit amazing cities and temples. This is blog is a midterm project for my History 112 class.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Thesis Statement

The Aztecs were a highly developed society in central Mexico from 1300 to 1521, until the Spanish Conquest of the Aztec Empire occurred in 1519-1521. The Aztecs had an deeply rich culture and created many innovative political, agricultural, economical, tribute, and religious systems. The vast city of Tenochtitlan was the capital of the Aztec Empire and housed incredible temples, marketplaces, and numerous festivals and celebrations. During my trip, I will get to explore this amazing place and fully immerse myself in Aztec culture and events.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tenochtitlán and Visiting a Marketplace

(Public Domain)

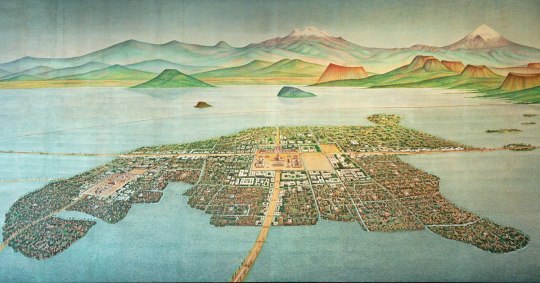

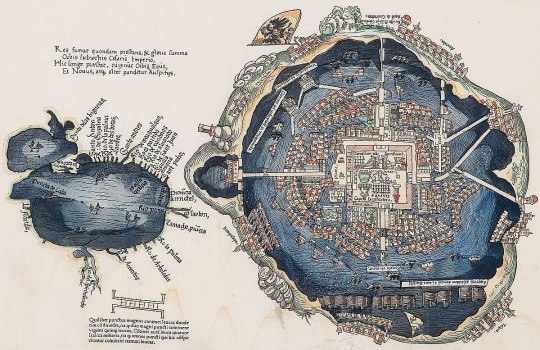

I have just arrived in Mexico, Central Mexico to be exact, and my first stop is Tenochtitlán! Tenochtitlán is the capital of the Aztec Empire, it is an incredibly vast city located on an island in Lake Texcoco (Publisher Not Identified). The exact date that Tenochtitlán was founded is unclear, but it was sometime in the 14th Century (Publisher Not Identified). As I approach the city, I stop to admire the view and I am blown away by what I see. Tenochtitlán is situated inside a large valley that is almost entirely made up by the lake and surrounded by enormous mountain terrain on all sides (Cortés). There are four causeways, a raised road, that connect the island city to the mainland (Cortés). Each causeway is approximately six-miles long and two spears’ length wide (Cortés). The city is broken up into numerous sectors that are separated by the causeways and canals, which are navigated by using canoes (Cortés). The location of Tenochtitlán definitely gives the Aztec people a natural protection from outsiders.

As I make my way across the closest causeway, I notice that the lake is separated into two different areas– one side with fresh water and a larger side with salt water (Cortés). On the outskirts of the city, there are plenty of farms and raised fields for produce (Smith, 4). There are many dams and canals that were made to irrigate the crops (Smith, 4). The farmland is incredibly impressive and shows how ingenious the Aztec agricultural system is (Smith, 4). After a very long trek, I begin to make my way into the city. As I look around, there are a vast number of homes, buildings, temples, and public squares (Cortés). It is impossible to miss the Templo Mayor, the main Aztec temple, which stands around 150 feet high in the center of the city (Atwood, 4). I cannot wait to visit the Templo Mayor later and admire the architecture up close!

After traveling down a few different streets, I notice a plethora of specialty shops and businesses. There are apothecaries, restaurants, barber shops, and many shops for various types of meat (Cortés). Moving on, I come across one of the large public squares where there is a market being held. The market is one of the most lively and impressive things that I have ever seen. There seems to be an endless number of vendors and people browsing their merchandise. There is a wide-range of merchandise being sold– jewelry, live animals, wine, honey, vegetables, fruits, cotton thread, clothing, and so much more (Cortés). I stop to look at the fresh vegetables, most of which came from the farmland that I passed earlier. Everything looks so enticing but I decide to purchase some cake and plums after talking with the vendor. There is also an audience house in this main square where magistrates make judgements on the controversies that arise in the market and decide how to punish lawbreakers (Cortés). I could see a lawbreaker waiting for their punishment so I decide to leave before things get ugly…I know how gruesome the Aztecs can be.

(After the Hernan Cortés conquered the Aztec Empire in 1521, many of the original Aztec buildings, temples, and homes were torn down. The city was rebuilt with Spanish style architecture and the Templo Mayor was replaced with the Iglesia Major cathedral, although the street layout of Tenochtitlán was left relatively the same.)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tenochtitlán Pictures

(Place of Publication Not Identified: Publisher Not Identified, 1550)

(Public Domain)

(Keystone View Company, Publisher)

0 notes

Text

The Templo Mayor

(Public Domain)

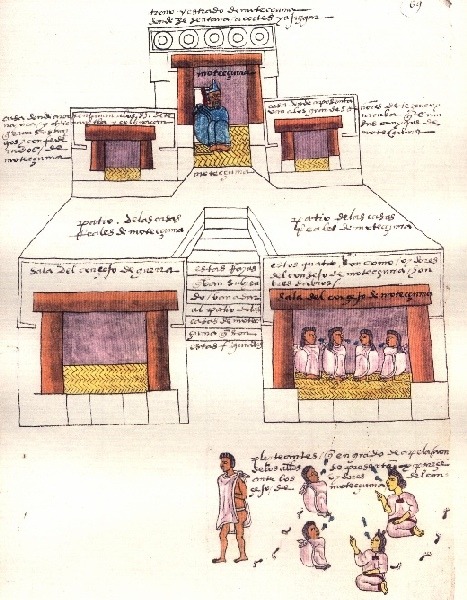

After my market excursion and a well-needed rest, I am off to visit the Templo Mayor! But before I talk about my experience, I want to talk about how the location for the temple was chosen. The Aztecs built the Templo Mayor in the spot where they saw the eagle upon a cactus because they considered this to be the holiest spot (Matos Moctezuma, 799). The Templo Mayor is in the center of the city and serves as the main temple to the Aztec people (Atwood, 29). There are many other temples in Tenochtitlán but the Templo Mayor is by far the most important to the Aztecs (Matos Moctezuma, 799). The Aztecs were very spiritual people and building temples was a way to honor the universe and the gods they worshipped (Atwood, 28). At the temples, offerings are made and human sacrifice is a common practice that is done to appease the gods (Cortés).

After a short walk from my lodging, I have arrived at the imposing Templo Mayor. The temple has been rebuilt several times over the decades, continuously becoming larger than the previous structure each time it was rebuilt (Matos Moctezuma, 803). The temple is massive and stands around 150 feet high, facing towards the west (Atwood, 29; Matos Moctezuma, 799). The base of the temple is a large platform with four or five stepped levels which travel up into a pyramid shape (Matos Moctezuma, 799). There are two large staircases that lead all the way to the top level of the temple (Matos Moctezuma, 799). At the top of the temple, there are two sanctuaries to honor Huitzilopochtli, the god of war and the sun, and Tlaloc, the god of water, rain, and fertility (Matos Moctezuma, 799). Between the two sanctuaries, there is a platform where the human sacrifices would take place (Mato Moctezuma, 799). Walking closer, I notice many intricate adornments to the temple structure– stone statues, alters with offerings, numerous glyphs, braziers, and sculptures (Matos Moctezuma, 804-806). Many of the statues and sculptures feature serpents, sometimes even half-man and half-lizard statues (Matos Moctezuma, 804-806). There is even a wall of skulls made from stucco and stone, I am thankful that they are not real human skulls…at least not at this specific site (Atwood, 29).

0 notes

Text

The Templo Mayor Pictures

(Public Domain)

(Public Domain)

(Public Domain)

(Public Domain)

0 notes

Text

Visiting Aztec Homes

(Smith, Scientific American)

It is my second day in Tenochtitlán! I am very excited because today I get to interact more closely with the local Aztec people. They have been kind enough to offer me a tour of their homes and it will be interesting to see the differences in how the nobles and commoners live. The Aztecs have a complex hierarchical society with clearly defined social classes within their community including the (1) emperor, (2) nobility, and (3) the commoners (Katz, 18; Smith, 1). Within the Aztec’s hierarchical society, there is also something called the calpullis, which were communities where the members regarded each other as family (Katz, 15). The calpullec, an elected leader, controlled the land and allowed community members to harvest from the it and pass it down to their heirs, but not sell the land (Katz, 15). Learning about the calpullis communities reminds me of a specific manuscript that I studied, The Codex Quetzalecatzin! The Codex Quetzalecatzin illustrates the land ownership and properties of the “de Leon” family line; I wonder if they were part of a calpullis (Mexico: Producer Not Identified). These communities were also responsible for making annual tribute payments to the emperor and nobles, which explains why the city of Tenochtitlán is so spectacular (Katz, 17; Smith, 1). Annual tributes consisted of things like clothing, feathers, maize, beans, cotton, gold, and spears in large quantities (Katz, 18-19).

For my first stop, I decide to visit one of the peasant villages. As I arrive, one of the villagers beckons me over and invited me to their home. The home owner informs me that this is a very stereotypical peasant house and many of the layouts are identical. The house is very small, measuring around 15 to 25 square meters (Smith, 4). There is a front door and a back door but no windows, so it is dark inside the home (Smith, 4). The interior of the home is very modest, furnished with woven mats on the floor, woven baskets, a shrine with figurines, and an incense burner fixed to the wall (Smith, 4). The shrine and incense burners are used in domestic rituals that focus on purification and curing (Smith, 5). We make our way back outside to sit on the patio and enjoy the sunshine. As I look around, I notice many activities going on like weaving and cooking in the common areas between houses (Smith, 4). In the area surrounding the houses, there are farming plots for crops like beans, maize, and cotton (Smith, 5).

After a lovely visit to the peasant village, it is time to see how the nobles live, so I make my way to the more urban areas. I immediately noticed that the houses are far bigger, at 540 square meters, and better constructed – made of lime plaster and elevated on stone platforms (Smith, 6). The houses have multiple levels, featuring beautiful flower-gardens on the ground floor and even on the rooftops (Katz, 19; Cortés)! The interior is filled with many objects that indicate their wealth like imported and decorated ceramics, bronze objects, and jade jewelry (Smith, 6). The nobles dress noticeably nicer than the peasants, showing off their position and wealth (Cortés). Some of the noble palaces feature elegant marble columns, floors with jasper inlay, and balconies extending over the gardens (Cortés). Visiting both the peasant village and these urban areas where the nobles live really shows how different the social hierarchy is in the Aztec Empire.

0 notes

Text

Aztec Home Pictures

(Smith, Scientific American)

(Public Domain)

(Public Domain)

0 notes

Text

Moctezuma Meeting Cortés

(Public Domain)

My third day in Tenochtitlán has been the most interesting by far. This morning I woke up to a flurry of activity happening all around me. I asked what was going on and apparently a large group of Spanish explorers are making their way into the city. I quickly follow the crowd, attempting to get a good view of the welcome party that was led by Emperor Moctezuma (Cortés). Moctezuma, dressed in his finest attire, looks very regal surrounded by his chiefs and numerous attendants to greet the visitors (Cortés). As we approach, I notice a vast number of Spaniards on horseback but there is one man that stands out among the group (Cortés). The leader looks incredibly familiar…it is the Spanish conquistador, Hernan Cortés! Cortés dismounts his horse to greet Moctezuma but is stopped by Moctezuma’s two chiefs (Cortés). The Aztecs must first perform a customary greeting, bowing to kiss the earth, which I assume is their way of showing respect to visitors (Cortés). Cortés finally meets Moctezuma and gives him a gorgeous necklace made of pearls and cut glass (Cortés). Similarly, Moctezuma presents Cortés with a gift of two necklaces with eight hanging shrimps of refined gold, wrapped in cloth made from red snail shells (Cortés). Moctezuma holds Cortés and the visitors in high-esteem; he almost treats them as if they are gods come to earth. Listening in on their conversation, Cortés assures Moctezuma that they are his friends and the Aztec people have nothing to fear from them (Cortés). I am not sure why but I get a very unsettling feeling when I look at Cortés as he speaks of his intentions…Finally, the group begins the walk back to Moctezuma’s palace for a welcome feast and Moctezuma and Cortés grasp hands as a show of affection (Cortés).

Moctezuma’s palace is beautiful! There is an enormous courtyard with a chess-board style pavement, multiple cages with many different species of birds, and cages with lions, tigers, wolves, foxes, and so many more (Cortés)! We make our way into the palace and it is full of Moctezuma’s subjects (Cortés). I feel so lucky to explore the palace and to be included in this lavish feast that we are about to have. We arrive in the large hall, which is Moctezuma’s preferred place to eat, and sit down on the leather cushions at the table (Cortés). Before the meal begins, water is brought out to cleanse our hands (Cortés). The young servants bring out an array of dishes, including all types of meat, fish, fruit, and vegetables (Cortés). Due to the colder climate, a chafing-dish with hot coals is put under every dish to keep the food warm (Cortés). There seems to be an endless amount of food and I do not even know where to begin! When each dish is empty, a new one is brought out and they do not use the same dish or chafing-dish with hot coals twice (Cortés). After the meal, fresh water is brought out again to cleanse our hands (Cortés).

0 notes

Text

Moctezuma Pictures

(Public Domain)

(Public Domain)

(Public Domain)

0 notes

Text

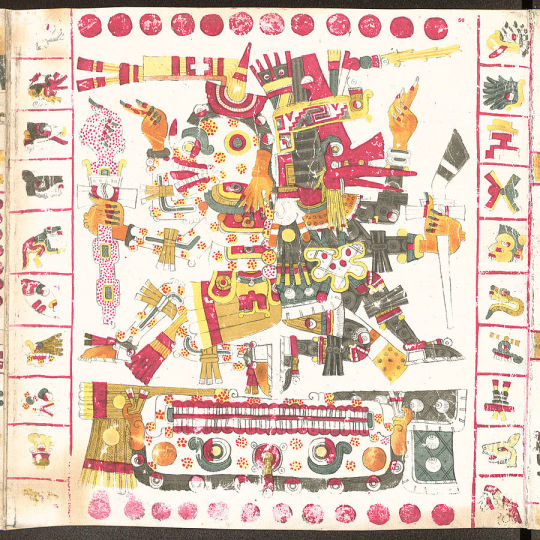

Aztec Festivals and The Massacre of Toxcatl

(Public Domain)

On my final day in Tenochtitlán, I get to learn about Aztec festivals and customs! I am especially excited because today is also when The Festival of Toxcatl starts! The Aztecs followed a very elaborate structure for their solar year where individual days and periods are dedicated to their gods (Graulich, 43). There are many different types of festivals that are held including sowing and harvest festivals, festivals of the dead, festivals of the sun and fire, and more (Graulich, 43-45). Specific festivals are held during both the dry season and the rainy season, as well as summer and winter solstices (Graulich, 44). For example, the Quecholli (dedicated to Mixcoatl), Panquetzaliztli (dedicated to Huitzilopochtli), and Toxcatl (dedicated to Tezcatlipoca) festivals are held during the summer and winter solstices (Graulich, 43-44). Each festival has their own ceremonies and rites that range from banquets, flower garland decorations, dancing, animal sacrifice, and human sacrifice (Graulich, 52). Human sacrifices are especially common in Aztec festivals and culture. During the Ochpaniztli (harvest feast) festival, a woman impersonates the earth goddess Toci, her throat is cut then she is skinned and a priest wears the skin to play the role of Toci (Graulich, 45).

It is now time for the main event, the Toxcatl festival is starting! The Toxcatl Festival is in the middle of each solstice and is dedicated to four deities: Mixcoatal, Huitzilopochtli, Tezcatlipoca, and Tlaloc. However, the festival is mainly dedicated to Tezcatlipoca, the lord of the night and moon (Graulich, 50). I am told that there is an important ritual that involves a man impersonating Tezcatlipoca to be sacrificed during the festival, which ensures the gods protection and favor (Graulich, 50). There is also music and dancing that is done over the course of many days, that must be tiring (Cortés). When we arrive to the festival, it is in full swing! The festival is held on the Sacred Patio which is full of dancers, musicians, and spectators as far as the eye can see (Cortés). The dancers and musicians are in the most amazing outfits, wearing sacred ornaments, embroidered cloaks, lip plugs, necklaces, and feathers (Cortés). The Aztec people’s happiness is contagious and I find myself enjoying the celebration. I find it odd that Moctezuma is not in attendance to oversee the celebration…I quickly realize why. The Spaniards come out of nowhere, viciously attacking everyone in sight (Cortés). I cannot contain my scream as I witness the Spanish attack the unarmed dancers and musicians first, slashing them with their swords (Cortés). I scramble to get away as the Spanish begin ruthlessly attacking the spectators and singers (Cortés). As I run through the streets, I notice that the guards have been sent away and the Spaniards are blocking the gates so that there is no hope of escape (Cortés). Moctezuma has made a grave error in trusting Cortés…war has begun in the city of Tenochtitlán.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Aztec Festivals and Gods Pictures

(Public Domain)

(Public Domain)

(Public Domain)

0 notes

Text

Picture Citations

Keystone View Company, Publisher. City of Mexico, the ancient tenochtitlan of the Aztecs. Mexico, 1900. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2021635011/.

Smith, Michael E. “Life in the Provinces of the Aztec Empire.” Scientific American 277, no. 3 (1997): 76–83. Photograph. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24995914.

Tenochtitlán. [Place of Publication Not Identified: Publisher Not Identified, 1550] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2021668313/.

0 notes

Text

Annotated Bibliography

Atwood, Roger. “Under Mexico City.” Archaeology 67, no. 4 (2014): 26–33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43825230.

Roger Atwood received his B.A. in History from the University of Massachusetts Amhurst, an M.A. in International Public Policy from Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, and an M.A. in History from Georgetown University. Atwood is an accomplished independent writer and consultant, he lived and worked for many years in Latin America. He is a published author and his writing has been featured in numerous newspapers, literary journals, and academic journals. Atwood’s article, Under Mexico City, was published in 2014 by a magazine called Archaeology. In Atwood’s article, he writes about Mexico City and the vast history that lies underneath the current city. The article provides information about the Aztecs and the city of Tenochtitlan, as well as their contact with Cortés and the Spanish. Atwood details the struggles that archaeologists face when attempting to dig for Aztec artifacts and showcases some of the found artifacts in the article. This article helps make a connection between the current Mexico City and the once great city of Tenochtitlan.

Cortés, Hernan. Second Letter to Charles V. From Oliver J. Thatcher, ed. The Library of Original Sources, Vol. V: 9th to 16th Centuries, pp. 317-326. https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/1520cortes.asp.

Hernan Cortés, or simply, Cortés, was born in 1485 and lived until 1547. Cortés was born in Medellín, Spain to a family of minor nobility. He studied in Salamanca and then spent several years as a farmer and notary to a town council in Hispaniola. In 1511, Cortés traveled to Cuba with Diego Veláquez, a conquistador and the first Spanish governor of Cuba, and became the mayor of Santiago. Cortés was a man of many accomplishments, but he was best known as the Spanish conquistador who led the expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire. During his expedition to Mexico, Cortés wrote five letters to King Charles V that detailed his accounts of the land and the Aztecs. I have chosen The Second Letter to Charles V because it provides Cortes’ incredible perceptions of the city of Temixtitlan. The letter describes the layout of the city, the surrounding terrain, various buildings and temples, the Aztec people, religious practices, and much more. Cortés is very thorough in his letter and the letter provides insight into the customs and daily life of the Aztec people in this area. Aside from providing details of Cortés feats, the letters were also meant to portray his actions in a positive light to the Spanish monarchy. This specific letter provides accurate imagery and details inside the Aztec community which will be very helpful for the descriptions in my travel log.

Cortés, Hernan. Letters From Mexico. Translated by Anthony Pagden. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986. http://web.archive.org/web/20000304002237/http://www.humanities.ccny.cuny.edu/history/reader/cortez.htm.

Hernan Cortés or simply, Cortés, was born in 1485 and lived until 1547. Cortés was born in Medellín, Spain to a family of minor nobility. He studied in Salamanca then spent several years as a farmer and notary to a town council in Hispaniola. In 1511, Cortés traveled to Cuba with Diego Veláquez, a conquistador and the first Spanish governor of Cuba, and became the mayor of Santiago. Cortés was a man of many accomplishments but he was best known as the Spanish conquistador who led the expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire. During his expedition to Mexico, Cortés wrote five letters to King Charles V that detailed his accounts of the land and the Aztecs. The Letter from Mexico is a firsthand account of Cortés’ first interaction with King Moctezuma. His letter portrays Moctezuma and the Aztec people as welcoming, offering any resources and things they have to Cortés as a show of good faith. Cortés goes on to describe the view, the Aztec attire, and Aztec customs. This letter will allow me to describe the generous nature of Moctezuma and the interactions between him and Cortés.

Graulich, Michel. “Miccailhuitl: The Aztec Festivals of the Deceased.” Numen 36, no. 1 (1989): 43–71. https://doi.org/10.2307/3269852.

Michel Graulich received a degree in the history of antiquity from the University of Ghent, a degree in art history and archaeology, as well as a doctorate in art history, from the Free University of Brussels. He was an accomplished Belgian historian that specialized in the study of ancient American cultures, especially relating to Aztecs. Graulich wrote many publications that interpreted Aztec rituals, including a book titled, Human sacrifice among the Aztecs, and contributed to various academic journals. In 1989, he wrote an article called Miccailhuital: The Aztec Festival of the Deceased in Numen, a journal dedicated to the academic study of religions. In this article, Graulich presents an interpretation of the Tlaxochimaco, also known as Miccailhuital, and Xocotl Huetzi festivals. In order to give some more context to these festivals, Graulich also explains the structure of the year and other Aztec festivals. Graulich provides a very descriptive account of the Aztec rites, ceremonies, and offerings that were made at numerous festivals. The article is particularly focused on the festival of the dead and the reasoning behind why the Aztecs celebrated them. Graulich’s work allows us to investigate which Gods the Aztecs worshipped, why they honored in certain festivals, and insight into these intricate Aztec ceremonies.

Katz, Friedrich. “The Evolution of Aztec Society.” Past & Present, no. 13 (1958): 14–25. http://www.jstor.org/stable/649866.

Friedrich Katz received a B.A. from Wagner College in New York and a Ph.D. from the University of Vienna. Katz was an anthropologist and historian who specialized in the history of Latin America. He wrote a thesis on Aztec society titled, Socio-economic relations of the Aztecs in the 15th and 16th centuries, which helped place available research on Aztec civilization into historical context. Katz received numerous awards for his work, including the Order of the Aztec Eagle from Mexico. In 1958, Katz wrote an article on Aztec society in a British historical academic journal, Past & Present. The article is titled, The Evolution of Aztec Society, and touches on a few aspects of Aztec society. Katz writes about three main points in this article: 1. The social organization of the Aztecs and how their society evolved into a class society, 2. How the evolution into a class society mainly impacted foreign subject peoples, which allowed for the stronger Aztec systems to survive and the calpullis to occupy a larger part of the land, and 3. The evolution of this social order had no link to the old world and the Aztecs did not entirely change their way of life, allowing them to be more productive because of their advanced agricultural systems. Another area that Katz discusses is how annual tributes worked in Tenochtitlan, including what items were given, which helps explain why Tenochtitlan specifically was so prosperous.

León-Portilla, Miguel. The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico. Boston: Beacon Press, 1962. https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/aztecs1.asp.

Miguel León-Portilla was a Mexican anthropologist and historian that specialized in Aztec culture. He attended the Instituto de Ciencias in Guadalajara, where he earned a B.A. and M.A. summa cum laude, and the Jesuit Loyola University in Los Angeles. León-Portilla went on to attend law school, taught at a Mexico City College, and began his studies at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). While attending UNAM, he completed his doctoral dissertation, La Filosofía Náhuatl estudiada en sus fuentes, which began his career as a scholar. León-Portilla worked to translate many Aztec and Spanish texts. He published The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico in 1959, which translates Aztec accounts of the Spanish Conquest of the Aztec Empire. I have chosen two of the translations from his book, The Speeches of Motecuhzoma and Cortés and The Massacre in the Main Temple. These accounts describe eyewitness accounts of the meetings between the Aztec and Spanish people, as well as the horrific attack that the Spanish carried out against them. The translations will allow me insight into the relationship between Motecuhzoma and Cortés, provide details of Aztec festivals and celebrations, and describe traditional Aztec attire.

Moctezuma, Eduardo Matos. “Archaeology & Symbolism in Aztec Mexico: The Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 53, no. 4 (1985): 797–813. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1464276.

Eduardo Matos Moctezuma received a M.A. in archaeology from the National School of Anthropology and History, as well as an M.A. in anthropology from the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Matos Moctezuma is a well-known Mexican archaeologist and directed excavations at the Templo Mayor from 1978 to 1982. The excavations led by Mato Moctezuma have unearthed incredible Aztec artifacts and locations that help us to understand Aztec culture, religion, and the Aztec empire. Matos Moctezuma has written numerous books and contributed to historical journals like The Journal of the American Academy of Religion. In 1985, he published an article titled, Archaeology & Symbolism in Aztec Mexico: The Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan which provides an in-depth look into his excavations of the Templo Mayor. In his writing, Mato Moctezuma attempts to uncover the relationship between economic structures and ideological forms. He wants to offer his interpretation of the symbolic order of the Templo Mayor and the society that the temple represented. This article also details the history and origins of the Aztecs, what surviving Aztec documents can tell us, Aztec structures, and details archeological findings.

Smith, Michael E. “Life in the Provinces of the Aztec Empire.” Scientific American 277, no. 3 (1997): 76–83. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24995914.

Michael E. Smith received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and a B.A. in Anthropology from Brandeis University. Smith is an archeologist that specializes in the Aztec archeology and currently holds the position of Professor of Anthropology in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change at Arizona State University. Smith has directed numerous fieldwork projects at Aztec sites in the Mexican state of Morelos and in the Toluca Valley. He is a published author and has written several books about the Aztecs, journal articles, and other publications. In 1997, Smith wrote an eight-page article titled, Life in the Provinces of the Aztec Empire, in The Scientific American Magazine. This article talks about excavation work that Smith and his team performed, attempting to unearth Aztec artifacts that tell us more about Aztec lives. Smith believes that it is very important to explore historical Aztec sites that were previously looked over and forgotten. In this article, Smith touches on the hierarchy of the provinces and what life was like for the various nobles and commoners that lived there. There are numerous pictures of the Aztec artifacts that were found during the excavations and artistic renditions of what the provinces may have looked like. The examples and descriptions from this article will help me create an accurate portrayal of Aztec markets, goods, peasant, and their homes in my travel log.

Tenochtitlán. [Place of Publication Not Identified: Publisher Not Identified, 1550] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2021668313.

This is a topographical map of Mexico City and the surrounding terrain from around 1550. The map was painted three decades after Hernan Cortés’ conquest of Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital. When looking at the map, you can see many physical changes that were made by the Spanish but there are still characteristics of the former Aztec city that survived. The layout of Tenochtitlán remains the same apart from new Spanish buildings. In the center of the map, the Iglesia Major cathedral can be seen along with numerous Spanish style buildings where former Aztec temples once stood. The artist who painted the map is unknown but based on the construction of the map and familiarity with the area, it is speculated that the map was made by an Aztec with European schooling. This speculation is accurate because the map demonstrates knowledge of Aztec life, plants, animals, and certain areas are labeled in Nahuatl, which was the language of the Aztecs. This map provides us with insight into city life post-Spanish conquest and the various changes that were made to Tenochtitlán.

The Codex Quetzalecatzin. [Mexico: Producer no identified, 1593] Map. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4701g.ct009133/.

The Codex Quetzalecatzin is an incredibly rare Mesoamerican manuscript from 1593. The manuscript is written in Nahuatl, the Aztec language, and features stylized graphics and hieroglyphs. The codex is very colorful, using pigments from plants and materials that reflect all other Aztec documents. The manuscript is written in Nahuatl, the Aztec language, and features stylized graphics and hieroglyphs. This specific codex depicts land ownership and properties of the “de Leon” family during this time period. The de Leon family were descents of Lord-11 Quetzalecatzin who was a major political leader in 1480, which is also the name featured in the codex. The codex also features some Spanish names for places and images which shows how the Aztecs adapted to Spanish rule. Another important part of this manuscript is that it features the names of indigenous leaders, which shows that certain Aztec elites were granted Spanish titled of nobility. The Codex Quetzalectzin is a crucial piece of history that helps when studying European contact with indigenous people. This specific codex is incredibly important because there are less than one-hundred Mesoamerican manuscripts that pre-date 1600.

0 notes