Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

FDA Approves New Painkiller 1,000 Times Stronger Than Morphine

FDA criticized for approving new painkiller 1,000 times stronger than morphine: 'You have blood on your hands'

The Food and Drug Administration approved a new opioid that's apparently 1,000 times stronger than morphine. Here's what you need to know. (Photo: Getty Images)

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is getting the side-eye after approving a painkiller that's said to be 1,000 times stronger than morphine. Critics point out that this comes amid an opioid epidemic in the United States - which led to more than 72,000 deaths in 2017 alone.

The drug is called Dsuvia, and FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, addressed the timing in a statement released late last week. “The crisis of opioid addiction is an issue of great concern for our nation,” he said. “Addressing it is a public health priority for the FDA. The agency is taking new steps to more actively confront this crisis while also paying careful attention to the needs of patients and physicians managing pain.”

Gottlieb also made the case for Dsuvia's approval on Twitter, and reactions weren't positive:

You have blood on your hands

- TheResistance Report (@AntiTrumpReport) November 2, 2018

You should resign.

- Charles Harris (@ChuckVapes) November 2, 2018

When there's some healthcare provider out there who OD's on this stuff for the first time, you can unequivocally tell yourself you killed them personally. Crazy how OD's work. One bad dose is all it takes for that person to never have an opportunity at sobriety again.

- Patrick (@patrick2278t) November 3, 2018

Why would you do this?

- Renee Rocks (@bluerockrz) November 4, 2018

Dsuvia is a sublingual (meaning it is taken under the tongue) form of sufentanil (a synthetic opioid) that's delivered through a disposable, pre-filled, single-dose applicator, the FDA says. It is restricted to being used in certified medically supervised health care settings like hospitals, surgical centers, and emergency departments.

Gottlieb also points out in his statement that it can help in special circumstances in which a patient may not be able to swallow, adding that there could be potential uses on the battlefield. There are also “very tight restrictions being placed on the distribution and use of this product,” Gottlieb says.

The medication won't be available at pharmacies and shouldn't be used for more than 72 hours.

“This has actually been on the market as an injectable for quite some time,” Jamie Alan, PhD, an assistant professor of pharmacology and toxicology at Michigan State University, tells Yahoo Lifestyle. “It's not a new drug; It's a new dosage.” Alan says the concern around the drug is “valid given the potential for abuse.” However, she adds, the safeguards that the FDA has put in place should help.

Dsuvia “works exactly the same as morphine and other opioids do,” Alan says. Meaning, it binds to opioid receptors in your body to help reduce or block pain. “This drug just will work a lot more than morphine - it's 1,000 times stronger,” she says.

The serious potential side effects are the same as with morphine, Alan says, including decreased respiration, trouble breathing, coma, and death. “It doesn't tend to cause itching or blood pressure issues like morphine, but the concerning side effects are still there,” she says.

Dsuvia isn't designed to be taken by people who haven't taken morphine in the past, Alan says. Rather, it's for patients who have “used opioids before and probably have some sort of tolerance to opioids,” she says. It's also designed to be used in “really specialized situations” including end-of-life care and pain that isn't helped by other opioids, Alan says. “This is certainly not first- or second-line pain medication,” she says. “It shouldn't be given to Joe Shmoe coming in with a broken arm.”

via: Korin Miller,Yahoo Lifestyle: https://www.yahoo.com/lifestyle/fda-criticized-approving-new-painkiller-1000-times-stronger-morphine-blood-hands-184606918.html

0 notes

Text

Former NBA Star Shares Story of Opioid Addiction

Former NBA Star Shares Story of Opioid Addiction

Chris Herren had it all until an opioid addition destroyed his career. The former Boston Celtics player shared his story with students in Tuscola, IL.

youtube

via: Ryan Burk https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sHtJPa7fsgM

0 notes

Text

Behind The Shield: Dr. Gregory Smith M.D.

Dr Gregory Smith is a pain and addiction specialist based in California. His documentaries “American Addict” and “The Big Lie” are powerful looks at the opiate crisis and overuse of psychiatric medications. We talk pain, DNA testing for addiction, opiate deaths, CBD and much more.

via: Behind the Shield: https://soundcloud.com/user-866502338/dr-gregory-smith-episode-97

0 notes

Text

The Impact of Opioid Addiction in Diverse Communities

Voices from the Field: The Impact of Opioid Addiction in Diverse Communities

On May 9, 2018, on behalf of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the National Network to Eliminate Disparities in Behavioral Health (NNED) convened a Virtual Roundtable. In this Roundtable, panelists and participants were invited to discuss opioid addiction and treatment in communities of colors and strategies for community-based organizations to engage in cross-systems work. In addition to raising awareness and increasing knowledge of participants around opioid addiction and treatment, the Roundtable dialogue aimed to draw attention to cultural considerations, persistent disparities, and the cultural divide that play a role in the opioid crisis.

Panelists: Margarita Alegría, Ph.D. Devin Reaves, M.S.W. Dr. J Rocky Romero Jacob Davis, MPH

youtube

via: NNED: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xlE_6VL4tXM

0 notes

Text

Melania Trump lends support to Americans battling opioid crisis

Melania Trump lends support to Americans battling opioid crisis

First lady speaks at New Hampshire event

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

First lady Melania Trump onstage at event addressing the opioid crisis in Manchester, New Hampshire.

(CNN) – First lady Melania Trump made a rare appearance that included public remarks Monday to reiterate her personal commitment to those battling the opioid crisis.

“In my role as first lady, much of my focus has been towards understanding the negative effects the opioid epidemic is having on our children and young mothers,” she said in New Hampshire.

Trump mentioned neonatal abstinence syndrome, a little-discussed but devastating side effect of pregnant women addicted to opioids who give birth to babies either addicted to drugs or faced with withdrawal symptoms.

“Many young mothers are not even aware of this disease, so we must continue educating them about the real dangers of opioids on unborn babies,” she said.

Trump noted her visit last month to Cincinnati Children's Hospital, a facility that is at the forefront on studies of and treatments for neonatal abstinence syndrome. She also mentioned Lily's Place, a recovery center in West Virginia she visited in October that specializes in babies with the syndrome.

Trump has several times been the sympathetic voice in an administration frequently embroiled in upheaval and brashness, her compassionate side on display in the intermittent visits she has made to children in hospitals in the US and abroad.

The first lady did not attend a summit earlier this month at the White House of families and experts working to combat opioid abuse, but she referred to the event in Monday's remarks.

“I'm proud to support this administration's commitment to battling this epidemic,” said Trump, before introducing her husband.

The first couple embraced at the podium, where President Donald Trump called his wife “incredible” before outlining his plan to stop the drug epidemic.

via Melania Trump lends support to Americans battling opioid crisis

0 notes

Text

Are Americans addicted to pills?

Are Americans addicted to pills?

A new study from Consumer Reports claims that more than half of Americans are over-prescribed medications, and Dr. Jennifer Ashton discusses what people can do to limit the number of drugs they take.

youtube

via: Good Morning America : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ljBkwUsRTGE

0 notes

Text

Addicted in America

Addicted in America

Give responsibility back to the states.

youtube

via:Rehab University: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-clOQHMs1Xs

0 notes

Text

Brett Favre on quitting Vicodin

I shook every night

youtube

via: Graham Bensinger: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1RMJIV3o6uI

0 notes

Text

The Opioid crisis is decimating the American workforce

How the opioid crisis decimated the American workforce

In northeastern Ohio, employers say they see jobseekers all the time who look like “the walking dead,” would-be workers struggling with opioid addiction. The problem is so great, reports economics correspondent Paul Solman, that it's had a noticeable effect on the nation's labor force.

youtube

via: PBS NewsHour : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jJZkn7gdwqI

0 notes

Text

Gregory A Smith MD American Addict the movie

From the makers of the hit documentary American Addict, American Addict 2 picks up where the first film left off and breaks even more new ground.

youtube

via Gregory A Smith MD American Addict the movie

0 notes

Text

American Addict (2012) – IMDb

Riveting look at the politics, big business and the medical industry that has made America the most prescription-addicted society in the world. America is less than 5% of the World's population but consumes 80% of the World's prescription narcotics. We have gone from being the land of the free to the land of the addicted.Riveting look at the politics, big business and the medical industry that has made America the most prescription-addicted society in the world.

Director: Sasha Knezev

Writers: Sasha Knezev, M.D. Gregory Alan Smith (based on the book by) (as Gregory Smith)

Stars: M.D. Gregory Alan Smith, Sasha Knezev

Watch FREE with Amazon Prime

via American Addict (2012) – IMDb

0 notes

Text

America Is Neglecting Its Addiction Problem | Policy Dose …

A Blind Eye to Addiction

Drug and alcohol addicts in the U.S. aren't getting the comprehensive treatment they need.

By Lloyd Sederer, Opinion Contributor

June 1, 2015, at 2:45 p.m.

More

Stop neglecting addicts.JULIE MCINNES/MOMENT/GETTY IMAGES

ADDICTION IS AMERICA'S most neglected disease. According to a Columbia University study, “40 million Americans age 12 and over meet the clinical criteria for addiction involving nicotine, alcohol or other drugs.” That's more Americans than those with heart disease, diabetes or cancer. An estimated additional 80 million people in this country are “risky substance users,” meaning that while not addicted, they “use tobacco, alcohol and other drugs in ways that threaten public health and safety.” The costs to government coffers alone (not including family, out of pocket and private insurance costs) exceed $468 billion annually.

Over 38,000 peopled died of drug overdoses in the U.S. in 2010, greater than the deaths attributed to motor vehicle accidents, homicides and suicides. Overdose deaths from opioids (narcotic pills like Oxycontin, Percodan and Methadone as well as heroin) have become the fastest growing drug problem throughout the U.S., and not just in large urban settings.

[ READ: The Republicans' King v. Burwell Problem ]

NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH/NATIONAL CENTER FOR HEALTH STATISTICS/CDC WONDER

Family dysfunction adds to the list of tragic consequences of our neglect. Addiction brings financial and legal problems (property and violent crimes) and increases domestic violence, child abuse, unplanned pregnancies and motor vehicle accidents. Addiction is also highly prevalent among jail and prison inmates, and in many instances, played a role in their incarceration.

Yet, and perhaps this is the most important – if not troubling – finding of all, only one in 10 people with addiction to alcohol and/or drugs report receiving any treatment at all. Compare this to the fact that about 70 percent of people with hypertension or diabetes do receive treatment. Can you imagine accepting that degree of neglect if that were the case for heart or lung disease, cancer, asthma, diabetes, tuberculosis, stroke and other diseases of the brain?

And when a person with an addiction seeks treatment, odds are they will be directed to Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous or another 12-step recovery program. AA is a spiritual approach to recovery, developed in the U.S. by Dr. Bob Smith and Bill Wilson in 1935. A 2006 Cochrane Review, internationally recognized for evidence-based treatment reviews, reported that between 1966 and 2005, studies examining AA and 12-step programs concluded that “no experimental studies unequivocally demonstrated the effectiveness of AA” in treating alcoholism.

[ READ: Focus on Prevention to Cut U.S. Health Care Costs ]

The April 2015 issue of The Atlantic featured a story by Gabrielle Glaser titled “The Irrationality of Alcoholics Anonymous.” Glaser wrote that AA works for 5 to 8 percent of those who use it, citing an estimate by retired psychiatry professor Lance Dodes. Yet AA or 12-step programs remain the sole or core element in most private and recommended programs in this country. A forthcoming documentary, “The Business of Recovery,” exposes the private addiction treatment industry for it's predomination of the 12-step approach – with fees in the tens of thousands of dollars per month.

What is missing from the vast predominance of private or 12-step-based services is a comprehensive approach to managing addiction. Treatments have been developed for addiction that go well beyond AA. These include motivational techniques and cognitive-behavioral therapies. For those who want a non-medicinal and group approach, there is SMART Recovery, which, unlike AA, does not accept that individuals are powerless and seeks to help participants find their strengths and use them.

Perhaps the most neglected interventions for addiction are medication-assisted treatments. Medications are available that reduce cravings, deter use and help prevent relapse. These include naltrexone, acamprosate, Antabuse and methadone. And among the most promising and underused medication-assisted treatment is buprenorphine (Suboxone), a medication taken sublingually that can be one answer to our national epidemic of pain pill and heroin addiction. Buprenorphine, for example, is prescribed at a doctor's office for up to 30 days, and thus does not require attending a daily programwhere medication is dispensed, as it generally is in methadone programs. A bill was introduced in the Senate that would enable greater access to this medication.

[ READ: EEOC's Proposed Rule on Employee Wellness Programs Threatens Health Privacy ]

Psychiatric News reported on a recent speech by National Institute of Drug Addiction Director Dr. Nora Volkow, in which she explained that we once thought “addicts sought out drugs or alcohol because they were especially sensitive to the pleasure-inducing effects of dopamine.” In fact, the opposite prevails. Volkow said that “addicts are actually less sensitive to the effects of dopamine,” they reported. “They seek out drugs because of the very potency with which they can increase dopamine in the brain, often at the expense of other pleasurable natural stimulants that do not increase dopamine so dramatically.”

This neurological discovery helps explain alcoholic or drug cravings as well, Volkow said, as addicts are vulnerable to environmental triggers, like the sight of alcohol or a bar, contact with friends who share a drug life and exposure to substances in media – even including reports of addict deaths. Cravings and the heightened response to triggers are part of why addiction pirates an addict's behavior and renders them unlikely to pursue everyday life's pleasures and responsibilities. Treatments that target cravings and reduce the power of triggers are among our best hopes for recovery – and they now exist.

America has turned a blind eye to addiction. No wonder so many people walk into walls when paths of recovery are possible. Criminal justice approaches and interdiction are ineffective; they have become prohibitively expensive because they don't work and can make matters worse. It's time to give treatment a chance. But treatment must incorporate modern medical and psychological approaches, not only adhering to a tradition of spiritual recovery. Until we do that, more Americans will die, societal costs will continue to escalate, families will be bankrupted and cast asunder and communities will remain at risk for the crime that untreated addiction spawns.

Lloyd Sederer, Opinion Contributor

Lloyd Sederer is an adjunct professor at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health … READ MORE »

via America Is Neglecting Its Addiction Problem | Policy Dose …

0 notes

Text

America's opioid crisis has become an “epidemic of epidemics”

America's opioid crisis has become an “epidemic of epidemics”

A memorial calling into question God's existence in Huntington, West Virginia, on April 20, 2017. Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images

Rising intravenous drug use has created new public health epidemics of hepatitis C and deadly bacterial infections.

On the one hand, the young mother who came into the Kanawha-Charleston Health Department clinic in Charleston, West Virginia, last fall had good news for the doctors there: She'd been off heroin for four days.

Yet she was far from well. She had a painful dental abscess in her jaw that was causing yellow pus to drain out of her ear. She had hepatitis C. She'd recently missed her period and was worried she might be pregnant with her third child.

The staff at the clinic, which is also a needle exchange, told me they estimate that at least 70 percent of their patients who use intravenous drugs are seeking not just fresh needles but treatment for hepatitis C, which they developed during drug use and can cost $20,000 to $90,000 to treat per person. Others have another kind of dangerous infection called bacterial endocarditis, or a combination of the two.

The United States often measures the severity of its opioid crisis in drug overdose deaths. Driven by prescription opioids, heroin, and the deadly synthetic opioid fentanyl, drug overdoses claimed 64,000 lives in 2016 alone, more than the entire death toll during the Vietnam War.

Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images

Paraphernalia for smoking and injecting drugs after it was found during a police search in Huntington, West Virginia, on April 19, 2017.

But on top of the skyrocketing overdoses, there is a related public health crisis that's largely overlooked and gravely underfunded. Opioid and heroin use is causing a dramatic spike in new hepatitis C infections, as well as dangerous bacterial infections that, if left untreated, can cause strokes and require multiple open-heart surgeries. Doctors and public health officials also fear America is on the brink of more HIV outbreaks, driven by intravenous drug use.

With the federal government slow to act, small needle exchange clinics like the one run by Charleston's city health department are on the front lines, desperately trying to stop or slow the spread of these infections by treating them and encouraging patients to seek addiction treatment.

“This really is an epidemic of epidemics,” said Dr. Michael Brumage, the Charleston health department's executive director. “The number of overdoses does not convey the full scope of the tragedy that's playing out in front of us.”

Lawmakers and federal officials often cite $45 billion as the amount of money needed to treat the drug crisis, but experts say the real number to treat addiction and disease brought on by drugs is likely four times that. It would account for costs like curing hepatitis C ($20,000 to $90,000 per person) and open-heart surgery for bacterial endocarditis ($100,000 to $200,000). A bipartisan spending bill Congress passed last month contains $6 billion in funding for opioid abuse and mental health treatment, which local officials say is nowhere close to what's needed.

With little help from the federal government, clinics like Kanawha-Charleston are badly underresourced in their fight against drugs and the diseases they cause.

“I feel like I probably just see the tip of the iceberg on this because I'm typically seeing the sickest folks in the hospital”

America's opioid epidemic started in the 1990s and early 2000s when doctors began prescribing opioids for pain. Due to a combination of factors, including pharmaceutical companies pushing pills, doctors believing the drugs were safe, and incentives for a fast, efficient health care system that prioritized quick fixes, opioid prescriptions proliferated. The US is by far the leading prescriber of opioids in the world.

As prescriptions for addictive opioids like OxyContin became harder to come by, some people turned to heroin.

But the proliferation of intravenous drug use has led to a syndemic, or “multiple diseases feeding off of one another,” according to Tufts University public health professor Thomas Stopka.

One risk is infections from dirty needles, injection tools, and water to mix drugs. People often think of shared needles as the culprit for infection, but simply using the same needle or spoon to cook drugs multiple times is also a risk factor, as is not sanitizing skin or needles with rubbing alcohol.

Then there's the matter of what's actually being injected. Some drug users in Charleston use toilet water to mix their drugs, according to clinic staff. Sometimes, they'll draw water out of the brown, silty Kanawha River, said Abdul Muhammad, 56, a local Charleston resident and drug user who attended a Narcan training session at the clinic this fall.

“A lot of people are careless,” Muhammad said, speaking of the young drug users he sees. “They don't get the capacity of the dangers.”

When bacteria builds up in needles or in the cookers used to mix drugs, it gets shot into a person's bloodstream along with the drug, where it can travel anywhere throughout the body. Bacterial infections like this are called endocarditis; they are most dangerous when they reach the heart valve, causing nodules of bacteria to build up.

“If the infection is left unchecked and undiagnosed, it can become several inches in length and width and look like a sail billowing throughout the heart chamber,” said Dr. Jonathan Eddinger, a cardiologist at Catholic Medical Center in Manchester, New Hampshire.

There are 40,000 to 50,000 new cases of bacterial endocarditis in the US each year, but it's not known exactly how many come from injecting drug use. One study found the prevalence of drug-induced endocarditis and other serious infections nearly doubled between 2002 and 2012, from about 3,421 cases nationwide to 6,535.

What's particularly worrying about the potential rise of these infections among drug users it that on average, they cost more than $120,000 per patient to treat. Out of the $15 billion hospitals billed to treat opioid patients in 2012, more than $700 million went to treating patients with infections.

Catholic Medical Center is one of the two main hospitals in New Hampshire's largest city, and it has seen a sharp rise in bacterial endocarditis. In 2008, doctors saw one or two cases of infected heart valves per month. By 2016, that had risen to about eight to nine cases per month, Eddinger said.

“The number is probably enormous,” he said. “I feel like I probably just see the tip of the iceberg on this because I'm typically seeing the sickest folks in the hospital.”

Sometimes patients require multiple complicated surgeries, including open-heart surgery, with no guarantee that one will be enough if the patient can't stay clean.

Endocarditis patient James Pernal found that out the hard way, after about six or seven years of IV drug use. Vox contacted Pernal on the online forum Reddit after he wrote about his experience on a page for people who had experienced bacterial endocarditis. When Pernal messaged back, he was in still the hospital, recovering from his latest bout of the infection. Earlier in the year, endocarditis had given him his first stroke and nearly killed him, he said.

“When I got to the hospital I was rushed to ICU,” Pernal wrote. “Had no idea I had a vegetation growing in my mitral valve. It ended up going into my brain causing the stroke.”

“You don't really feel anything from endocarditis,” he added. “It's not painful, but after being on antibiotics in hospital for a month, the corrosion and plaque on the exterior of my heart traveled to my foot, causing it to turn purple and look like Freddy Krueger's face. They said it could have gone to my internal organs and killed me overnight so I was lucky it just went to my foot.”

If caught early enough, an infection can be cleared up with an intensive regimen of antibiotics. But if it gets worse, patients as young as 20 or 30 are at risk of stroke. Doctors have to perform open-heart surgery to replace the infected heart valve, which can cost between $100,000 and $200,000. Patients often don't see a doctor until they realize something is seriously wrong with them, which is complicated by stigma or fear that the police could get involved, Eddinger said.

“We don't get them regularly until they're very ill,” he said. “They're embarrassed, quite honestly.”

After his stroke and the infection in his foot, Pernal couldn't walk for a few weeks, and he eventually had to have open-heart surgery so that doctors could repair his damaged valves. Pernal estimated he spent a third of 2017 in hospitals from an infection he got from dirty needles.

“Mostly, people get it from dirty needles,” he wrote. “I can't stress using a clean needle each time you dose. Honestly though I'd stress not even to go IV route. It's not worth the damage it can do. It's a way bigger issue than addicts think. Everyone thinks it won't happen to them, but it can and will.”

Cases of hepatitis C associated with intravenous drug use are rising too

Another serious unintended consequence of the opioid crisis is the fast-rising rate of hepatitis C, a virus that spreads quickly through dirty needles. The United States has seen a threefold increase in hepatitis C cases over the past five years; the number of new cases rose from 853 in 2010 to 2,436 in 2015, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

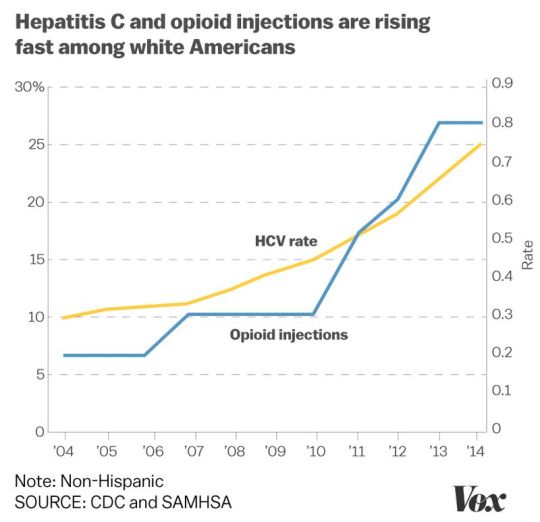

The opioid crisis has spurreda dramatic risein hepatitis C infections, especially among younger users. Between 2004 and 2014, there was a 400 percent increase in hepatitis C infections in Americans ages 18 to 29, according to the CDC. There's a similarly bleak picture for people ages 30 to 39, with a 325 percent increase in infections.

New research by the CDC suggests that this spike in hepatitis C infection rates is associated with a rise in intravenous drug use. As government researchers analyzed national and state data, they found infection rates rising at a similar trajectory to hospital admissions for opioid injection.

Christina Animashaun/Vox

Part of the reason hepatitis C rates are spiking so much is the virus is much more resilient than other viruses like HIV. Whereas the HIV virus dies quickly outside the body, the HCV virus (which causes hepatitis C) can survive longer and therefore is easier to transmit. If left untreated, hepatitis C can cause liver cancer or cirrhosis.

In West Virginia, the state arguably hardest hit by opioid addiction, hepatitis C cases have tripled in just the past three years, according to Dr. Rahul Gupta, West Virginia's health commissioner. Rural areas had more than double the rate of cases as in urban areas, according to a 2015 report from the CDC.

Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images

A woman suspected of acting under the influence of heroin shows her arms to local police in Huntington, West Virginia, on April 19, 2017.

The good news is that there is a cure for hepatitis C; the bad news is that the cheapest course of treatment costs more than $20,000 and ranges all the way up to $90,000. Therefore, many state Medicaid programs have strict rules around paying for treatment.

One of the first patients at the Kanawha-Charleston clinic on a rainy fall day had recently discovered he was positive for the disease. (Clinic staff estimate 70 percent of the patients who come in have contracted hepatitis C through IV drug use.)

The man was soft-spoken and polite, with shaved silver hair, weathered skin, and holes in the knees of his jeans. He was carrying a black messenger bag full of used needles, which tumbled out into a plastic collection box when he turned it upside down. He asked clinic volunteer Sarah Embrey whether his insurance would pay for the hepatitis C cure. Embrey, a local pharmacist, looked at his state Medicaid card.

“You've got to be clean,” she told him.

West Virginia's Medicaid program only pays for it once in a person's lifetime, and if the patient is addicted to opioids, he needs to demonstrate he's been sober before insurance pays for the cure.

The man nodded. He said he had recently kicked heroin but was still shooting crystal meth.

“I feel like that was a big step,” he said.

“Syndemic” diseases feeding off each other cost our health system billions of dollars

It costs tens of thousands to perform open-heart surgery on a patient who has bacterial endocarditis. And there's no guarantee one surgery will be enough if patients continue to inject drugs. Eddinger has seen the same person in for a heart valve replacement multiple times; in fact, 25 percent of endocarditis patients in his hospital are repeat patients, about 250 over the past five years.

Not only is surgery costly, but the risk of complications goes up each time one is performed. The risk “goes up exponentially as they go in, and these folks aren't coming in healthy to begin with; they're coming in sick,” Eddinger said.

For all these reasons, University of Kentucky researcher Dr. Laura Fanucchi is adamant that evidence-based treatment like Suboxone, therapy, and counseling need to be offered to bacterial endocarditis patients, so that there's less of a chance they'll land back in the hospital in need of a second surgery.

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

A second bout of endocarditis “is often worse than the first, and these are young people,” Fanucchi said. “It's devastating.”

With little help coming from the federal government, needle exchanges are racing against time

Public health officials across the country are fearful that the drug crisis could precipitate an HIV outbreak. This happened in Indiana in 2015, when about 190 people were diagnosed with HIV from shared needles. The outbreak convinced the state's then-governor, Mike Pence, to allow needle exchanges to open up access to clean needles. It helped get the state's crisis under control, but even so, the cost to the state was vast.

Officials estimated each patient diagnosed with HIV would take $1 million of state money when health care and public assistance was factored into the total cost. That meant taxpayers were looking at paying at least $190 million to take care of 190 people. And that's just in one state.

Needle exchanges serve a dual purpose: making sure drug users are injecting with clean equipment to prevent infection, and getting dirty needles off the streets and disposed of properly. There is a collection box outside the health department that can hold 38 gallons of needles; it was full in the first five days. Once Charleston city officials collect the needles, they have a machine that sanitizes and crushes them up, turning them into small pieces of plastic that can be disposed of.

Robert Nickelsberg/Getty ImagesUsed syringes in the bottom of a trash bin at Howard Center in Burlington, Vermont, on May 24, 2016. The center provides a needle exchange program, supplies, counseling, and other services.

The Charleston health department only runs the clinic for five hours per day, one day per week, typically seeing about 400 people in that time. Most people come in for the clean needles, cookers, and cotton swabs, while others are seeking medical attention.

Needle exchanges are controversial because some people believe they enable drug use, but multiple studies have found them to be effective at reducing infection rates among drug users. In Charleston, the city's needle exchange has partnered with local doctors and behavioral health specialists to provide even more services to the local population - treating flesh wounds and infections in the clinic and trying to get drug users into treatment.

The price tag often cited by the White House and Congress to treat America's opioid crisis is $45 billion - though there's little sign that amount will ever be allocated. And experts say that's just a quarter of what's needed. If you take into account the costs of treating the diseases associated with addiction like hepatitis C and bacterial endocarditis, the number is closer to $186 billion over a decade, according to Dr. Richard Frank, a health economist at Harvard.

This gets to another problem public health providers are seeing: It's much easier to get addicted in America than it is to get clean. A 2016 report by the surgeon general found that just 10 percent of Americans with a drug use disorder obtain specialty treatment.

Clinic staff in West Virginia can hand out clean needles, treat wounds, and encourage people to seek treatment, but in many states, there are not enough available beds at treatment facilities and not enough drug maintenance programs offering Suboxone or methadone to meet the needs of Americans with drug addiction.

Preventive and harm reduction programs like the Kanawha-Charleston clinic in West Virginia cost money upfront, but if they are able to prevent the spread of bacterial endocarditis, hepatitis C, and HIV in their area, they could ultimately save the taxpayers a lot of money in the long run, the Charleston health department's Brumage said.

“If we prevent one to two cases of endocarditis, this program pays for itself,” he said.

Join the conversation

Are you interested in more discussions around health care policy? Join our Facebook community for conversation and updates.

via America's opioid crisis has become an “epidemic of epidemics”

0 notes

Text

Finally, proof: opioids are no better than other medications for some chronic pain

Finally, proof: opioids are no better than other medications for some chronic pain

A first-of-its-kind study compared opioids to non-opioid drugs in patients with persistent back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis. Its results are devastating.

Long before opioids snowballed into one of the worst public health crises in American history, Dr. Erin Krebssuspected there might be a problem.

As a medical fellow in North Carolina in 2004, Krebs noticed many of her patients were on prescription opioids like OxyContin - now well known to increase the risk of addiction and death - for common ailments like low back pain and arthritis. Even after patients took the drugs for months or years, however, Krebs noticed they weren't helping.

So she looked to the medical literature to find studies about long-term opioid use - and there weren't any. Most trials ran for no more than eight to 12 weeks and focused on the rather useless question of whether opioids performed better than no treatment at all.

Today, opioids are still prescribed at an astoundingly high rate. But thanks to Krebs, now a researcher at the Minneapolis VA Center and an associate professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota, doctors and patients will finally have a high-quality clinical trial that answers the rather simple question she's been asking herself for more than a decade: Do opioids help patients with chronic pain in the long run? Are they worth all that risk?

The answer, according to her newly published JAMA study, is a resounding “no.”

Krebs is the lead author on the first randomized trial, comparing chronic pain patients on prescription opioids (like morphine, hydrocodone, and oxycodone) to patients on non-opioid painkillers (like acetaminophen or Tylenol, naproxen, or meloxicam), measuring their pain intensity and function over the course of a year.

The striking result was that the patients on opioids did no better than those taking the opioid alternatives - despite the much higher risk profile of opioids. At one year, the opioid takers even reported being in slightly more pain compared to the non-opioid group.

“I think this is going to shake things up,” said Roger Chou, a professor at Oregon Health and Science University who was not involved in the research. “The belief has always been opioids are the most effective pain medicine, certainly for acute pain and even for chronic pain. This [study] turns that on the head.”

“It's not just that opioids were not better - they were a little bit worse”

It's lately become clear that America's opioid epidemic has been fueled mainly by heavy marketing of the drugs by pharmaceutical companies and doctors' prescribing tendencies.

Though the overall rate of opioid prescriptions has decreased slightly in recent years, there is still an alarming quantity of opioid painkillers being doled out - many of them for chronic pain issues like low back pain. As of 2016, 67 prescriptions were being written for every 100 Americans. The same year, there were 14,500 opioid-related deaths.

All this time, doctors and patients have been operating with an incredible scarcity of high-quality evidence about how opioids work in people over the long term.

A systematic review on opioids for chronic non-cancer pain in 2006 examined 41 trials - and the average duration of the studies was only five weeks. “There's only been one trial that's gone out to a year, and that was a head-to-head study comparing morphine to fentanyl,” explained Chou. In other words, no long-term study has compared what opioids do to patients' pain and how the drugs stack up against other types of treatment.

Krebs wanted to fill in that gap. For the paper, which she co-authored with colleagues in Minnesota and Indiana, she recruited 240 patients at Veteran Affairs primary care clinics who had experienced severe chronic back pain, or hip or knee osteoarthritis, for at least six months.

The researchers then assigned half of the patients to opioids and the other half to opioid alternatives, and followed them up for a year. As a first step, the opioid group got morphine, oxycodone, or hydrocodone/acetaminophen first, and the non-opioid group tried acetaminophen (i.e., Tylenol) or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (i.e., Advil). If these prescriptions didn't work, the doctors adjusted the patients' medications, trying other drugs from a pre-set list.

Before the study and at three-month intervals over the course of a year, the patients scored their pain according to two main outcomes: functionality (or how easily they were able to go about their daily lives) and intensity.

At the start of the study, the opioid and non-opioid groups scored almost exactly the same on both measures. By 12 months, the groups looked indistinguishable once again on their functionality scores - they had both improved a little.

But when it came to pain intensity, the opioid group actually reported being in a little more pain than the non-opioid group at one year. What's more, the opioid group experienced twice the number of side effects - most commonly, drowsiness, grogginess, nausea, difficulty focusing, constipation, and stomach upset.

“It's not just that opioids were not better - they were a little bit worse,” Chou said.

“Opioids aren't better than non-opioid medications,” Krebs summed up, “and we already knew from other research they are far more risky - and that the risk of death and addiction is serious.”

There was already randomized controlled trial evidence suggesting opioids don't offer extra relief for patients in acute pain who came into emergency rooms. The new study now adds to the evidence that they also don't deliver any extra benefit compared to non-opioid drugs for chronic pain patients. “You don't want to take the riskiest possible medication when something less hazardous would work just as well - and that's basically what we found here,” Krebs said.

Even more remarkably, the researchers measured the patients' perceptions of opioids: The participants in both groups in the study believe they would work better than non-opioids. Typically, the medical interventions patients believe are more potent - like surgery or an injection over taking a pill - wind up have a stronger effect. But with opioids, that still wasn't the case. “That probably made the opioid group look better than it would've if [the study] had been blinded,” said Krebs.

Opioids are still being commonly prescribed - but the way we think about managing chronic pain is changing

With all the data on opioids' harms and the absence of evidence that they help people on average, the medical community has moved away from encouraging doctors to prescribe the drugs.

In February 2017, the American College of Physicians advised doctors to prescribe “non-drug therapies” such as exercise, acupuncture, tai chi, yoga, and even chiropractics for low back pain, and avoid prescription drugs or surgical options wherever possible. In March 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also came out with new opioid-prescribing guidelines, urging health care providers to turn to non-drug options and non-opioid painkillers before even considering opioids.

The new study should bolster the guidelines, Chou said. But he also warned that it doesn't mean opioids are never appropriate. The study is the first of its kind, and its results will need to be replicated in other settings.

“I don't think opioids should necessarily be completely abandoned for chronic pain based on a single study done in the VA system. But I think this should have some impact on how people think about opioids for chronic pain,” he added.

Beth Darnall, a pain psychologist at Stanford University, called the study “rigorous science” but also emphasized that there are some individuals who may still benefit from opioids.

“The future is more precision pain medicine - truly characterizing each individual and having science to inform which treatment works best for each patient. We don't yet know who is the sub-population for whom low-dose opioids may be beneficial,” she said. And until then, she warned that the pendulum shouldn't swing too far away from opioids.

Still, America has a long way to go before the pendulum has swung too far. Medical practice changes slowly, and opioid prescribing remains rampant across the US. As of 2018, the opioid epidemic has only continued to worsen, and America is an outlier among nations for its outrageously common opioid habit. It's not clear more or better science earlier on could have prevented the epidemic. But studies like Krebs's should certainly make doctors think twice before prescribing the drugs.

Join the conversation

Are you interested in more discussions around health care policy? Join our Facebook community for conversation and updates.

via Finally, proof: opioids are no better than other medications for some chronic pain

0 notes

Text

U.S. emergency rooms see 30% jump in opioid overdoses as crisis worsens

U.S. emergency rooms see 30% jump in opioid overdoses as crisis worsens

Increase may be due to changes in volume and type of illicit opioid drugs being sold on the streets

The Associated Press

A man injects heroin into his arm at Kurt Cobain Memorial Park in Aberdeen, Wash., on June 13. The U.S. government says non-fatal overdoses visits to hospital emergency rooms were up about 30 per cent late last summer, compared to the same three-month period in 2016. (David Goldman/Associated Press)

Emergency rooms across the United States saw a big jump in overdoses from opioids last year - the latest evidence the country's drug crisis is worsening.

A government report released Tuesday shows overdoses from opioids increased 30 per cent late last summer, compared to the same three-month period in 2016. The biggest jumps were in the Midwest and in cities, but increases occurred nationwide.

“This is a very difficult and fast-moving epidemic and there are no easy solutions,” said Dr. Anne Schuchat, acting director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Overdose increases in some states and cities may be due to changes in the volume and type of illicit opioid drugs being sold on the streets, health officials said.

OxyContin maker Purdue says it will stop marketing opioids to U.S. doctors

Prescription opioids no better than over-the-counter drugs for chronic pain, study shows

The report did not break down overdoses by type of opioid, be it prescription pain pills, heroin, fentanyl or others.

The CDC recently started using a new system to track emergency-room overdoses and found the rate of opioid overdoses rose from 14 to 18 per 100,000 ER visits over a year. Almost all those overdoses were not fatal.

The CDC numbers are likely an undercount. Its tracking system covers about 60 per cent of the ER visits in the whole country and some people who overdose don't go to the hospital, Schuchat said.

Opioids were involved in two-thirds of all overdose deaths in 2016. That year, the powerful painkiller fentanyl and its close opioid cousins played a bigger role in the deaths than any other legal or illegal drug.

More recent CDC data shows overdose deaths rose 14 per cent from July 2016 to July 2017, but that data doesn't distinguish opioids from other drugs.

© The Associated Press, 2018

via U.S. emergency rooms see 30% jump in opioid overdoses as crisis worsens

0 notes

Text

Suspected opioid overdoses increased 30 percent in one year, CDC report says

CDC report says:

Suspected opioid overdoses increased 30 percent in one year

The opioid epidemic shows no signs of leveling off, as the most recent report covering most of the U.S. shows an average 30 percent rise in suspected overdoses, in just one year.

Watch Video

Between July 2016 and September 2017, the suspected opioid overdoses across 45 states increased by an average of 30 percent, according to a new report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

One of the surprising statistics in the report: The problem holds true for both men and women, across different age spans, races and regions.

In the time period studied, 15.7 per 10,000 emergency room visits were for opioid overdoses. The largest increases were in the Midwest –- a 70 percent rise - and the West, with a 40.3 percent hike.

The new figures are based on an updated tracking system that helps hone in on the correct number of opioid-related cases faster, the CDC said. The agency now uses emergency department statistics, in addition to hospital billing data.

“Long before we receive data from death certificates, emergency department data can point to alarming increases in opioid overdoses,” said CDC Acting Director Anne Schuchat, M.D. “This fast-moving epidemic affects both men and women, and people of every age. It does not respect state or county lines and is still increasing in every region in the United States.”

More detailed data was collected in 16 states. In large metropolitan areas, the data showed a 54 percent increase in suspected opioid overdoses, although increases were noted in rural centers, as well. Two states showed more than a 100 percent increase in opioid ODs, including Delaware, at 105 percent, and Wisconsin at 108 percent. The next highest levels were in Pennsylvania, at 80 percent higher, and Illinois which rose 65 percent.

There was some good news; some states showed lower rates of opioid overdoses. Two states that have had historically high rates, Kentucky and West Virginia, showed lower numbers of emergency department visits.

“Kentucky saw a decrease of 15 percent … which may reflect some fluctuations in drug supply,” Schuchat said today.

Northeastern states such as Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Rhode Island showed lower emergency room visits, but there is not enough data to know if local interventions were the reason.

In short, the opioid epidemic is not plateauing, and the CDC said these numbers point to a need for enhanced prevention and treatment efforts in emergency departments.

Rapid data that is increasingly available from emergency departments can serve as an efficient way to alert local communities if there is a rise in overdoses.

Because those who have experienced a past overdose are more likely to overdose again, the emergency departments can also use this data to target high-risk patients and connect them to case managers and community resources for substance use disorders.

“To successfully combat this epidemic, everyone must play a role,” U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams, MD, MPH, said.

The CDC recommends that local health departments should stock enough naloxone for first responders to reverse an overdose and that public safety and law enforcement should coordinate with local public health officials in high drug trafficking areas. The agency also suggests that community partnerships can help provide treatment.

Dr. Najibah Rehman is a resident in the ABC News Medical Unit.

via Suspected opioid overdoses increased 30 percent in one year, CDC report says

0 notes

Text

Special Report: Opioid Epidemic Looms Over Valley Communities in Txas

In 2016, there were reported 2832 deaths linked to opioid addiction in the state of Texas.

youtube

via: KRGV: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JLC-7uE_SMg

Published on Mar 1, 2018

0 notes