Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The 7 Tiers of Ascendency Part 1. The Map

I like to think if you looked at the above and had a guess of what it might mean you would be close to the sentiment of the idea. It is simply a way of abstracting the kind of goals a crew may have at each tier. But to expand on that point... There's something about BitD that to me feels, inexplicably, like an old arcade game where crossed with a competitive virtual reality environment (if you have ever seen the 2001 polish film, Avalon, by Mamoru Oshii, you'll have a better sense of what I mean). The challenge, the enemy, is the environment, the world. The city is trying to kill you. Your goal is to survive. In this world, the only way to survive is to thrive; you stand on the necks of your opponents to climb higher or you don't. BitD already has Tiers which vaguely reflect groups' relative power but that is not quite the same as the kind of schlocky 'level 1' and 'level 2' progress structure that I am outlining here.

Also, one complaint I have heard levelled against BitD is that the character can become more powerful than their environment too quickly and too easily. I'm not commenting on that but I will say my taste is that a game is more satisfying when you have to work to beat level 1 and when eventually succeed at Level 3 after being beaten by it many times.

In the next post, I'm going to talk about '7 Tiers of Ascendency', what each might mean and what each might look like and how you might use it in your games to give give players a kind of direction for their ambitions and to give GM's an abstracted sense of what a crew may be aiming to achieve. But first...

Blades in the Spire

The savant amongst you will have noticed the picture is adapted from Slay the Spire, another excellent game about climbing higher, and I use it to capture a few ideas;

Giving crews 2 or 3 scores per level.

Discrete bands of challenge can justify an exponential increase in difficulty between them (Tier 2 twice as difficult as Tier 1, Tier 3 twice as difficult as Tier 2 etc.)

I like goal being not to 'win' but to see how high you can go. Remember this is a game about making stories. Ime, characters comfortably retiring is as close as you can really come to failure.

Giving crews several discrete options for their scores. Some will find this helpful, some won't.

Connected points on the map help players form and see narrative arcs. If we do take the Heist job to rob the Marimon's caravan, then it may mean next we need to silence his security chief. These arcs can be done projectively and/or retroactively.

Each point on this map could be a kind of score (or even a non-score objective or event), and so the players might enjoy picking a path between 'assassination', then 'heist', then completing/disrupting a ritual.

This creates an opportunity to compel diversity in the kinds of score the crew takes, pushing Crews out of their comfort zones and mastered skills after Tier 1 or 2. Smugglers needing to steal, Thieves needing to protect... this can be very useful for encouraging crews to diversify their skills and hence and/or keeping the challenge level high.

Similarly, it can be the case that there is no path to Tier 3 that doesn't go through at least one of many different kinds of heist.

It can be fun to make and share this map ahead of time or conversely leave it blank and players to fill it in as they go though I would say leaving some record of the missions and scores they didn't take can be deliciously juicy for story building later on.

Perhaps the most important thing to bear in mind is that the crew still decided what each of these scores are. I think it's fine to say 'At some stage you will need to complete a Heist/Theft' but make sure that where, when, and what is stolen remains firmly up to them. A little structure, not too much.

0 notes

Text

It's not about what you know, it's about who - Levelling up in a Narrative-centric RPG

Players like to level up. They like their characters to get more powerful, more experienced, more influential in the world they exist in. In traditional RPGs, this is simply done by increasing their stats - +1 to hit, +5 to hide and so on.

But Blades in the Dark is not a mechanical game. Not chiefly, at least.

And one criticism I have heard of it, is that once characters in BitD do start levelling up, they can only really 'level up' in the traditional sense by getting an extra die to roll on their action tests... and when a 4+ = success, another dice makes any real failure quite unlikely.

That can be a problem for telling a story. A story without failure is a story without conflict, without risk. So how do you square this circle?

One option is to give the PCs 'level ups' that don't fit on their character sheet - narrative level ups, rather than mechanical ones. This is most easily done through establishing contacts and relationships. Each character can (in lieu of or as well as) start building a roster of unsavoury contacts they have throughout the city that will open all kinds of doors, literally or figuratively, for your crew.

Following is a few simple examples of what these might look like, by playbook.

Whisperer- Knowing Your Demons

For most people, this might mean coming to terms with yourself but for the Whisperer this could have a much more literal meaning. Undine will channel water for you, breaking a damn, surging water from a canal, making it rain, if you let her flood somewhere of her choice. Mortos will take a life if you give him a life in exchange. Vincent will allow you to see through someone else's eyes on the condition he gets to take your eyes when he needs them, turning you blind for the duration. Arboros gives you momentary omnipotence and ticks the appocolypse clock forward.

Spider - The Enemies of your Enemies

In a previous post, I talked about showing the crew their relationship with other agents, people, crews, etc. An advanced Spider doesn't just know the relationships you have with them but knows the relationships they have between each other. The Spider has little birds informing you when relationships between the Red Sashes and City Guard are getting tense over a shipment that never made it to where it was suppose to go.

Lurk - Professional Respect

Formal thieve's guilds were never really a thing but there is something to be said about mutual professional respect. You knew Arienne back from when you were both urchins daring each other to climb higher on the cathedral walls. But now rumour has it she is the one who cracked into the Isil tower. Maybe she will tell you how she did it. Maybe she'll show you.

Cutter - I seen what you did to Tommy

People have seen what you do. They have seen the blood splatter in the alley ways and the scars left across the faces of previously respected and feared hard 'uns. Some people have had knightmares about your coming to call. Some of those people are likely to let you through or tell you what you want to know with very little trouble indeed.

Hound- Somebody's Always Watching

You see things. Standing in shadowed corners, watching from alcoves, hunched beside brick chimneys looking down on the street... you see things that nobody else sees. You see who was meeting behind the Argent Gardens after Ash every night and back again before Coal. You see who is sneaking out of bedroom windows and who is sneaking in. You see Councillor Tray, all hooded up, heading down the slip steps to meet another cloaked character beneath the bridge. What useful things to see.

Leech - Know a guy who knows a guy

Maybe the easiest to see, the Leech builds a web of contacts that can get them what they need. Grabbus distills webrot fungi like nobody else and Maritilda sneaks holy artefacts from the Church every Sunday after ceremony. There's a roofer on Rack Street who has been bottling the condensate from the roof Alduous Lerman's house after he noticed it was weirdly corrosive. An importer from the south knows a lot more than she lets on (to most people) about who is carrying Limegold into the city.

Slide- Cupid's Arrow

That time you seduced Provost Martin O'Malley to get access to the special collection... he has been writing to you since. In fact, he has been infatuated, in love, in adoration, obsessively writing to the slide since. As has Stephanie Albright, the Chief Sparkwright's wife. These are imagined as cards players can pull out of their sleeves to get special knowledge, insider information, know something that improves a roll or offers a way in to a score. When you don't want to just fill in another circle on a character sheet, owning special and valuable knowledge can be a welcome alternative.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

npcs from my blades in the dark campaign (that i never stop thinking about)

798 notes

·

View notes

Text

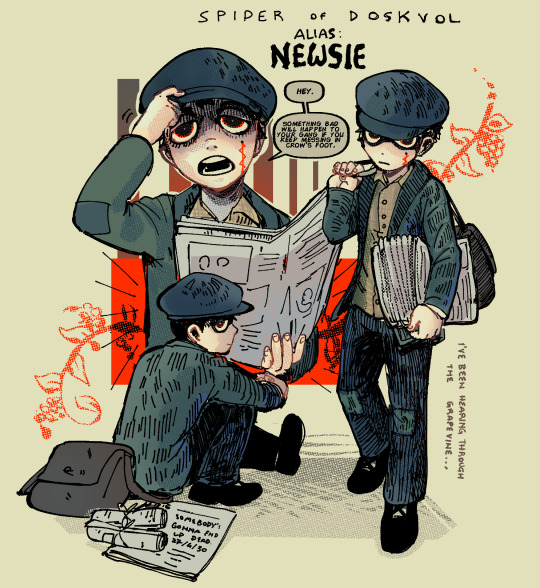

THE SPIDER OF DOKVOL

IS JUST A NEWSPAPER BOY

388 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another illustration for our Blades campaign, this time of the mysterious faux-automaton known as "the Sleeper": actually the transfigured soul of Haniyya the Radiant, second wife of King Euryalus Pandion and last queen of Akoros--here pictured with @catchaspark's PC Aphra Chesky sneaking in the back.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Web of Relationships

One of the core tensions in BITD is your crew's relationship with the other factions in the game.

If you draw a dodecagon (12 sides), each point can represent a faction and you can keep your crew's relationship with them clearly displayed in the same (nice) diagram.

Yes there are more than 12 factions in Duskvol but realistically your crew will not have a relationship with all of them.

They won't even have a relationship with 12, quite possibly, so it's advisable to start with a line or trianble between the crew and one or two factions they encounter first and add more as they appear.

What's fun about this is is that you can then connect those points to each other as your crew discovers the relationships those factions have between each other. Very valuable information indeed..

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heartbeat Scale

Blades in the Dark has something very valuable that many TTRPGs lack; the ability to hop, skip, and step over time parameters quite easily.

It's perfectly common for you to roll to Survey a dock for traffic over a a month or two. Similarly, you may need someone's name... and to get it, one of your crew might spend several weeks Consorting to find it.

Maybe in the downtime after a big score, your crew spends months consolidating their hold while the thugs you transgressed make progress in their revenge.

I call this the Narrative Scale.

Classically, you may take a single Prowl to not just climb one wall, but this wall, cross the court yard quietly, and slip a foot between the servants door and its frame, to keep it from locking, and quietly step inside. That may take any number of seconds or minutes.

Let's call this the Action scale.

That 'scale' tends to zoom out more than it zooms in, in my experience.

But in some instances, it is neither months nor minutes but seconds, and fractions of a second, that we want to dwell in.

Sitting at a felted table, your character clocks the quiet click of a pistol. Your compatriot tries to flick you a card from his hip and you have to catch it, without anyone noticing. You can hear your breath catching and what you do in the next half a second will determine whether you live or die.

I like to call this the Heartbeat scale.

It's the kind of timeframe where time slows down as adrenaline aggressively pours through your veins and arteries. It's the kind of timeframe where it feels like the volume of what's happening is turned down... until you can hear your own, throbbing heartbeat.

It's the very moment that matters most.

Afterwards, maybe when the jig was up, the Head smuggler let the mask drop that they knew who you are all along, where they were never really going to let you leave. It's in that moment that you kicked the table, snapped a wrist and ran.

It's back to the action scale as you slide down bannisters, and crash over carts and tables to get out as fast as you can.

And it's back to the Narrative scale when you are back in your hideout and know that they are looking for you and it won't be too long before they find you.

Scaling in and scaling out helps add a tempo and contextualise the narrative arc of a score and its surrounds in a way that can feel quite visceral and taut and bitter.

51 notes

·

View notes