Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

I ’ve drawn this image because I am tired. Tired of the invisibility of asexuals. Tired of people talking about asexuals as if they knew all situations. Tired of people who say they don’t want and/or should not enter the LGBT community because they are not oppressed.

Okay, do you think that living in a world where absolutely everything is sexualized is not being oppressed? Do you think that not being able to say it freely for fear of being judged is not being oppressed? To live in a world in which absolutely everything is sexualized is to live in a world that is not yours. You feel out of place in many situations. I have received, and seen receiving, harmful comments and contempt, even from people I have always considered my friends. And not only friends, family too. Having a partner is horrible in many ways, you spend your days waiting for the time to come, and when it happens you have two options, or accept and do something you don’t want to do, or explain it and hope the other person understands it. It is living in a constant fear of rejection and in the end, when it ends up happening, you feel guilty, when, of course, it’s not your fault. And we could give a list of endless examples with personal cases in which probably many of us would feel identified.

That, ladies, gentlemen and other genders, is called oppression.

Personally, about the LGBT, I would not like to be in a collective that does not respect us, if they end up accepting it, would be great, because having a very low or no spectrum of sexuality is also a way of living asexuality, especially when asexuality, like sexuality, It is NOT a choice.

Well, speaking now about drawing, I’ve made a maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus) because it is a not well known animal and I like it a lot. You are free to use the image (if you can credit me or let me know I would appreciate it very much). I’ve also thought about doing some drawings for aromatic people and maybe genderfluid, I will try to do it in the future.

63 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A friend told me that Marco surely shaved Jean fondly, and he dreams now about that. I have drawn it.

89 notes

·

View notes

Photo

That moment you realize there’s a Phara hunting you

44 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I was just wondering if you think it'd would be plausible for an ergative-abs system to evolve from the passive construction in a nom-acc language? Let's say maybe the active construction becomes less fashionable or polite and the passive becomes the the voice used for most sentences?

Yes, this is precisely how split-ergative systems that are split based on tense arise (cf. Hindi).

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historia Interna del Idhunaico y otros detallitos...

Pues este va a ser el primero de una serie de posts sobre Memorias de Idhún, donde voy a construir el idhunaico. Es un proyecto FAN, no os toméis esto como canon, aunque si Laura Gallego lo canonizara no estaría nada mal [emoji de los ojos]. No sé si esto lo va a leer alguien pero aquí lo dejo. Antes de empezar con palabras, fonología y gramática, vayamos a cómo voy a decidir (y he decidido) las cosas y como el idhunaico evolucionó dentro del propio mundo Así que, sin más dilación: LA HISTORIA INTERNA DEL IDHUNAICO Y OTROS DETALLITOS Vale, no sé muy bien para empezar. En el canon no hay muchos detalles sobre la historia de Idhún. A ver, sí los hay, pero no al nivel de Canción de Hielo y Fuego o El Señor de los Anillos. No lo toméis a mal, no es una crítica. Es simplemente un hecho. Esto deja más libertad a los fans para crear sus headcanons Así que voy a contaros lo que opino del asunto. Nos vamos a situar pre-Talmannon, lo que vendría a ser el final de la primera era y el principio de la segunda (la cronología de Idhún es confusa... teóricamente las eras cambian cuando se da una conjunción astral entre las lunas y los soles, algo que debería ser regular y predecible [como los eclipses] pero la duración de las eras varía muchísima...). Por aquel entonces, después de los 15.000 años que duró la primera era, las razas están distribuídas a lo largo de Idhún, con sus diferentes culturas, pueblos, reinos y civilizaciones. Y por supuesto, lenguajes. Podemos imaginar que uno de los reinos humanos se había extendido para conquistar el resto. De este reino unido vendrían muchos nombres de los actuales reinos, y muchos nombres de persona, como Alsan, por ejemplo. Mientras, en Derbhad pasaban otras cosas. Podemos imaginar este bosque como lo que ocurría en el Amazonas no mucho tiempo atrás: miles de culturas diferentes con miles de familias lingüísticas. Algunas de ellas se expandieron formando civilizaciones dentro del bosque. Hasta que en una de ellas nació Talmannon. Y ya sabéis el resto, que si Sheks, que si szish y conquistó todo Idhún. Con esta conquista expandió el idioma de su gente (seguro que su cultura no lo pasó nada mal, y que el odio a Talmannon vino de la propaganda de otras culturas feéricas *guiño guiño*). Este idioma es el conocido como Idhunaico Antiguo, el precedesor del Idhunaico Moderno (el que se habla en el tiempo del libro) y el Idhunaico Arcano, usado para la magia. Esto requiere cierta explicación: antes de Talmannon cada cultura usaba la magia con su propio sistema, pero durante el gobierno de este señor se reformó y unificó (básicamente se creó) la orden mágica, usando antiguas torres y creando nuevas para la experimentación, y estandarizando el sistema usando el Idhunaico Antiguo como medio. La diferencia de uso entre la conversación y la práctica mágica produjo el aislamiento entre el idhunaico conversacional que acabaría derivando en Idhunaico Moderno y el del uso mágico que acabó dando origen al Idhunaico Arcano. Esta relación entre Talmannon y los magos produjo el odio hacia la magia de la era posterior. El antiguo reino humano, que había sido una región dentro del Imperio de Talmannon, acabó fragmentándose durante la era siguiente y eso produjo los reinos humanos y bueno... no sé si esto llegará a alguien pero si gusta puedo poner más cosas sobre la historia headcanon de Idhún... idk...

Tenemos entonces un idioma que se ha instaurado como lingua franca del continente, al estilo Latín, y que debido a la interacción entre culturas no se fragmentó en diferentes lenguas hijas, sólo en 2: el conversacional y el mágico. Además, debido a su estatus como lingua franca, en la transición entre antiguo a moderno, el idhunaico adquirió muchos prestamos de los idiomas que se hablaban antes de su imposición: las lenguas yan, las humanas, el celeste, las lenguas feéricas del bosque de Drackwen, etc. ¿QUÉ HE HECHO Y QUÉ VOY A HACER? He cogido el pull de palabras canon que existían, así como nombres de fauna, lugares y personas. A partir de aquí, analizando los patrones, discriminé lo que podía ser idhunaico y lo que no. Por ejemplo, los nombre varu poseen clústers consonánticos que no aparecen en otras palabras (al menos con tanta frecuencia): Gablu, Glesu, Blenu, Agli. Los nombres celestes aparecen con muchos clusters vocálicos y cierta predilección por ser bisílabos con codas nasales. La aparición de la letra sólo se da en Qaydar, Qelora y en Kar-Yuq, siendo el primero un humano (con algo de sangre feérica), la segunda su tía abuela, de la que nadie sabe la raza (corregidme, plis) y el tercero un Shur-Ikail. Bien podemos decir que todos son humanos. Qaydar nació en Even, un pueblo perteneciente a los reinos humanos, aunque al norte de Derbhad, lo que puede explicar su ascendencia feérica. Así que se puede decir que la es un grafema que representa un fonema presente en los sustratos humanos, pero no en el idhunaico. No encontramos la letra excepto en Drackwen y Covan, lo que indica que ningún fonema se representa por ese grafema en el idhunaico, pero sí en otro idioma (quizá humano). Y así. Ya haré un post sólo de etimologías y de lo que se origina en el idhunaico antiguo y lo que no. Extrayendo esas palabras, disñé una fonología del Idhunaico Moderno, ya que todas las palabras del canon refieren a elementos de la realidad de ese momento, es decir a palabras de ese idioma (aunque sean más arcaicas, como Limbhad), intentando siempre respetar la romanización que había creado la autora. A partir de aquí, simulé procesos evolutivos fonológicos y obtuve la fonología del Idhunaico Antiguo. Con esta fonología, diseñaré una gramática, que evolucionaré para crear la del Idhunaico Moderno. Y, también, evolucionaré la fonética y la gramática del antiguo para crear el Idhunaico Arcano. Al final de este proyecto, uno podrá hablar, escribir y leer los tres idiomas Idhunaicos (ya me gustaría que esto ganase repercusión :')). Voy a crear posts de todo esto. Antes de acabar este, un par de palabras (3 de hecho) con las que he tenido problemas particulares: -Drak. IA: [ˈdrakˠ] ; IM: [ˈdrak] . Significa Dragón. Pero claro. Es convenientemente parecida a Dragón en castellano, catalán, inglés, latín... No me gusta que ocurra esto. Entiendo que es la creación de la autora y eso, pero, ¿no sería más realista si fuese un nombre totalmente diferente? Lo he intentado solucionar desde una perspectiva histórica. "Dragón" viene del latín "dracō", que a su vez viene del griego "drákōn", que significa "gran serpiente, pitón, dragón". Esta palabra griega está relacionada con "drakeîn", una palabra que tiene un significado relativo a "ver claramente". Explico esta similitud de la siguiente manera: cuando los dragones iban y venían de Idhún a la Tierra no vinieron solos. Algunos feéricos los acompañaron. En algunas zonas del mundo, los dragones se presentaron en ortros idiomas de Idhún. En Grecia, fueron presentados por los feéricos que hablaban Idhunaico Antiguo como Drak'. Como algunos de los dragones podían ser visionarios, esto hizo que los griegos relacionasen el significado con "ver bien, ver claramente". Y luego del griego se extendió al latín, y de ahí al castellano, catalán, francés antiguo (del que saltaría al inglés) y tal... -Trask. IA: [ˈtraskˠ] ; IM: [ˈTrask] . Lo mismo. Qué curioso que se parezca a Trasgo, en castellano. Qué curioso. Podemos usar la misma explicación: en la Península Ibérica aparecieron trasgos y otros feéricos que hablaban Idhunaico Antiguo, e importaron la palabra. Por suerte, la etimología exacta de "Trasgo" es desconocida, así que podría ser... -Keles. Esta simplemente me mata. En teoría significa Celeste. Los celestes se llaman EN CASTELLANO así debido a su asociación con el viento y a su coloración azul celeste (y a porque la autora lo quiso hacer así). Es curioso que en idhunaico su nombre sea tan similar. Es por eso que he decidido darle otra etimología. "Keles" viene del propio idioma celeste (al menos de uno de ellos), de /qeleʂ/, la forma plural de su autónimo. El Idhunaico Antiguo no poseía ni los fonemas [q] ni [ʂ], pero sí una [kˠ] velarizada (fuerte) y una [s] sin velarizar (débil). Esto hizo que se incorporara como [kˠe.ˈles], lo que acabaría derivando en [ke.ˈles]. Se escribiría por tanto con K fuerte y S débil (ya hablaré de esto). Nada que ver con el cielo, nada que ver con el azul. De hecho, la palabra para cielo en IA/M es "Yalu" [ja.ˈlu]. En fin, ya iré comentando más cosas!

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sacabambaspis 470-455 Ma For quite some time this fish was believed to have a rhombic tail. But deeper studies of a Fossil cluster revealed that this wasnt the case and it in fact looked pretty much like the brighter one here. The FULL form of Sacabambaspis tail is not entirely known and the tailend of no other sacabambaspis has been discovered. Depicted is a highly speculative sexual dimorphism, combined with a mating wiggle. next week I step away from the jawless fish for a moment.

240 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Uh oh. It’s a Star War. I drew these for Patrons, mostly in livestreams, back around the time TFA came out. It seemed like an appropriate time to share them publicly…with some apologies. >_> Happy holidays, everyone! —————- Lackadaisy’s on Patreon - there’s extra stuff!

43K notes

·

View notes

Photo

🐢 Remembering the slow yet captivating crawl of evolution. ~ @thecrashcourse Big History series.

18K notes

·

View notes

Text

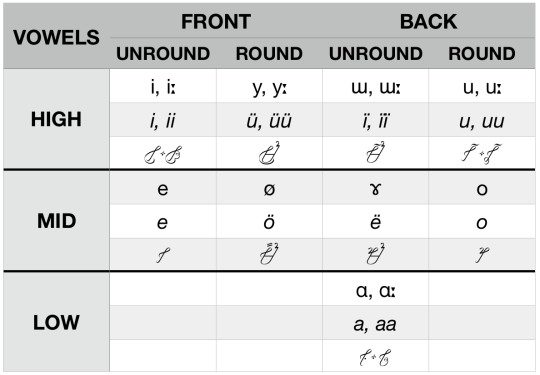

Övüsi: The Elvish Language from Bright

The Elves in Bright run the world. They’re literally in charge of everything, and they look down on everyone else. They’ve always been around (which is another way of saying I’ve now forgotten where geographically they were supposed to have originated), and though their language has changed, the Elves have prevented borrowings from other languages from “tainting” the “purity” of theirs.

The language itself has changed over the centuries, but older words have been preserved in their original forms for use in magic. Both modern Elvish and a couple of words of older Elvish appear in the film. The name of the language is Övüsi Kieru, which literally means “Elvish Tongue”, and despite having 9 vowel qualities, it does not have vowel harmony. The language is SOV and strongly head-final with thirteen cases and a verb system which is weird (I honestly still don’t get it).

Remember previously when I said I designed the Castithan language from Defiance to be spoken quickly—and how I failed? This time I tried to do it right—and I think I succeeded. You can really pick up some speed speaking this language, and the tongue twisters are minimal.

The orthography is a bit of a story. I created it to be excessively indulgent, and I think I succeed in that. When I showed the art department, though, they said it wasn’t excessively indulgent enough. They wanted more stuff about. So I had to take what, to my mind, was already a ridiculously gaudy writing system and make it gaudier. The result is, in my opinion, just silly in places. I suppose it’s in keeping with the Elves’ style of dress, but some of its excesses really tax credulity. You’ll see.

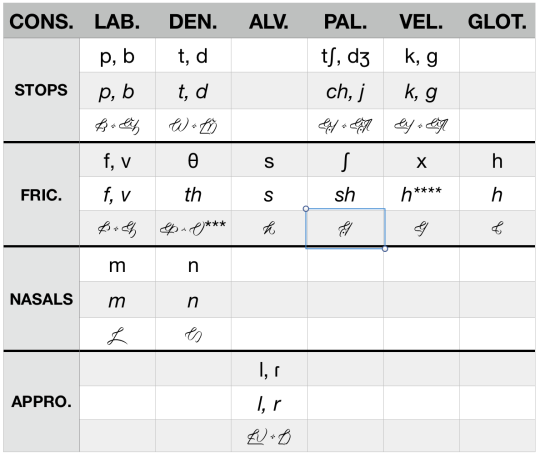

Below is the phonology and orthography of Övüsi:

Couple things here. First, you’ll notice long vowels for everything but mid vowels. This is my “Don’t make actors pronounce ee as anything other than [i]” sound change. Old long mid vowels broke, becoming a high vowel followed by a mid vowel, as in Finnish (so ie, üö, ïë, and uo).

You’ll also notice some unrounded back vowels. I was nervous about trying to do unrounded back vowels, but I figured since I was going to have constant access to the actors, I’d give it a shot. Turns out I had nothing to worry about. Those unrounded vowels are super easy for English speakers to pronounce. Basically I just said, “These are pronounced like this”, and then they said, “Oh”, and did them right every time. The front rounded vowels still caused problems, but the back unrounded vowels did not. I used diereses to indicate the unrounded back vowels for parallelism. It seems to have worked.

As a final note, the long opposite-rounding vowels have no separate form. This is because though the long vowels are phonemic (in that there are places where you must pronounce, e.g., üü as opposed to ü), there’s actually no way to write them in the orthography. Everything else that has a distinguishable form (as you’ll see) is either a form that was a licit long vowel at one time, or was (or currently is) a licit diphthong. That left nothing for the long opposite rounding vowels.

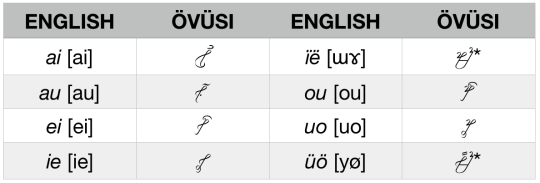

Here are the aforementioned diphthongs:

If you look at the forms for ie and uo, they should look rather familiar. That’s because these used to be the forms for *ee and *oo, and they’re simply read differently now. You’ll also notice that the forms for üö and ïë are identical to the forms for ö and ë, respectively. That’s because there’s no way to indicate the long form for these vowels, and those are the readings of the long forms of those vowels.

As you look at these, by the way, most of the extra lines and weird swooshes you see were added by request.

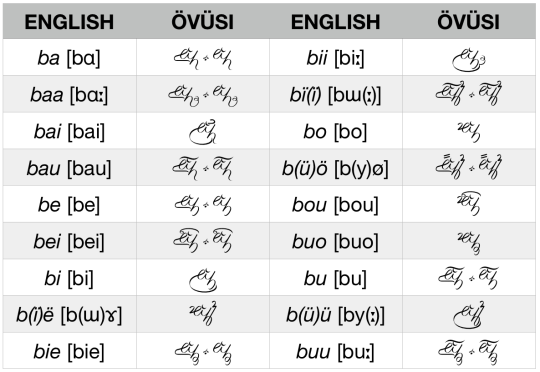

The consonantal base forms are as follows:

You can ignore the blue box; that was my bad there (screen cap). So like…stuff happened here. Basically, the short forms of stops became fricatives, but then there already was a *th, so all those words just got respelled. So the form with the three asterisks is usually pronounced [s] before [i], and elsewhere it’s [θ], but it’s not used word-initially, unless it’s before [i]. The form with four asterisks is an old consonant that’s no longer pronounced (it’s just regular [h] now), and so there are two [h]’s in this thing.

I added those ridiculous half moons because most stuff was wanted. Also, I thought r was fine on its own, but they wanted the bottom part to extend, so I extended it, along with l. Same extension happened with the word-initial flourish on f and v and like forms. I’m just looking at this now, and I’m like…seems unnecessary…

Anyway, the system is an abugida, which means there’s an inherent vowel, and modifications are added for other vowels. The inherent vowel in this system is short e. This is a fully executed consonant that’s hopefully large enough that you can see it:

You can also see the “capital” versions that occur for some consonant/vowel combinations above. Basically, when one of these occurs as the first character of a word, there’s an extra flourish. Where there are two glyphs above, the first has the flourish, and so is an initial form, and the other would appear elsewhere in the word. I had a lot of fun coming up with these, but now looking at the extra half moons, the extra loops, the extra double lines on bö… It’s just all too extra for me. But I know what it originally looked like, so I always have something to compare it to in my mind.

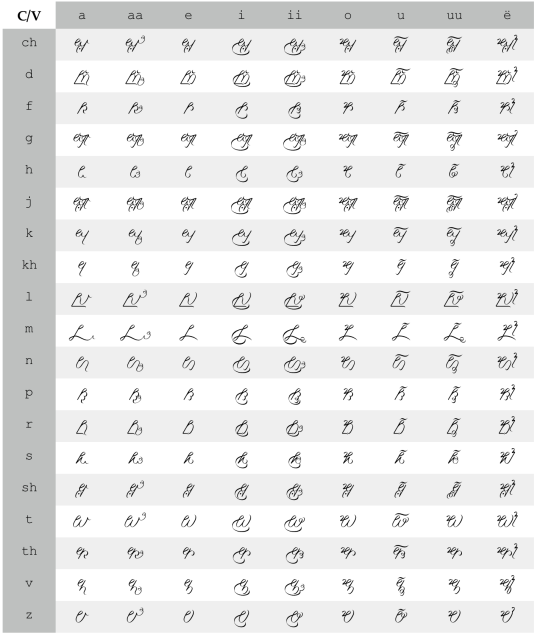

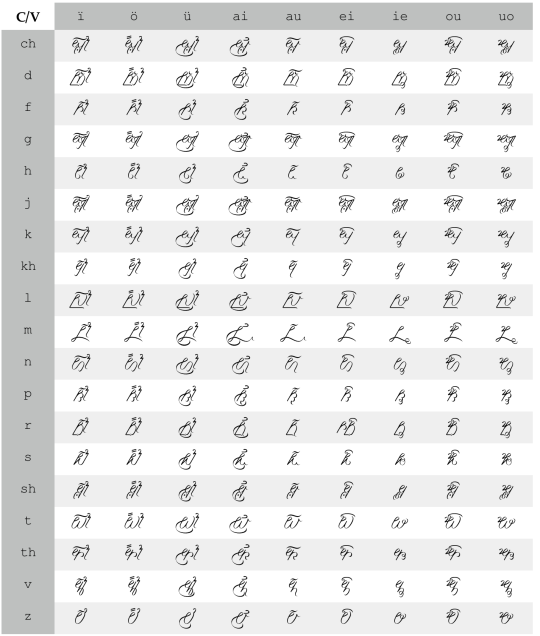

Now for the sake of completeness, though it’s going to make this really long, here is the fully executed version of every glyph split into two tables. Here’s table one:

And here’s table two:

Huh. Weird error in the rei cell… Included one two many r’s it appears… The character’s still there, though. (By the way, the keystrokes are written on the left there. This is for the font. What’s “z” there is the weird old *t sound that’s become [θ] and [s].)

There’s also a geminate marker that, when you see it, you’ll be able to recognize as a reference to Castithan. I’ll show it to you in an example later.

Nouns in Övüsi have a bunch of different declensions. It’s all based on whether the original form ended in a vowel of some kind or a consonant. At this stage of the language, no word can end in a consonant, and the only codas are reserved for the first member of a geminate, so lots of different things happened to these consonant-final forms. There’s no room to show every declension, but I can at least give you one, and give you a sense of the cases themselves. Here they are (singular/plural):

NOMINATIVE: thuoke/thuoki “bird(s)”

ACCUSATIVE: thuokie/thuokii “bird(s) (direct object)”

GENITIVE: thuoka/thuokai “bird’s/birds’”

INSTRUMENTAL: thuoku/thuokï “with the bird(s)”

LOCATIVE: thuokö/thuokü “near the bird(s)”

ABLATIVE: thuokau/thuokavi “away from the bird(s)”

ALLATIVE: thuokaalou/thuokaalli “towards the bird(s)”

INESSIVE: thuokannö/thuokannü “inside the bird(s)”

ILLATIVE: thuokou/thuokoli “into the bird(s)”

ELATIVE: thuokannau/thuokannavi “out of the bird(s)”

PERLATIVE: thuokausu/thuokausï “by way of the bird(s)”

AVERSIVE: thuokasshu/thuokasshï “avoiding the bird(s)”

VOCATIVE: thuokuo/thuokorii “O, bird(s)!”

If you look at these cases, you can probably recognize some of my favorite sound changes, and guess how some of them evolved (and in what order). The nice thing about having a nice big case system like that is it’s just there for you, like your best friend. You don’t really need to fuss about how to say stuff. Your best friend just says, “Shh, shh… Let me show you my cases.” And you take one and you’re good. Like hot cocoa in winter.

Now the verbs…

On a macro level, verbs agree with their subjects in person and number in the first person and sometimes the imperative, and just in person otherwise. Each verb has three stems: the imperfect, the perfect, and the future. Then, depending on whether the verb is dynamic or stative, there are three modes: the indicative, the passive, and the potential (statives lack the passive mode). A copula is used for emphasis, negation, and equation.

It’s best to see an example, and with verbs, the easiest to tease apart are the vowel-final ones. Here’s a table to consider:

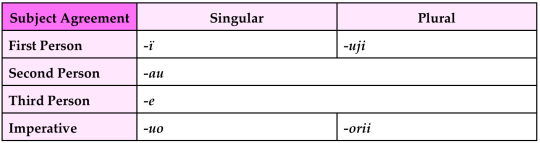

This is the verb mikaa, which means “to say” (most of the time the infinitive ends in -ie; it’s just non-e V-final stems that are different). As you can see, the stem part here is probably -i for imperfect; -has for perfect; and, of all things, bare for future. Then there are some more or less predictable suffixes added in the three modes. To those can be added agreement affixes, but they can also be left off. Depending on whether or not they’re added the end of the form changes. The first items in each pair are how the form ends if nothing is added. I’ll show you each in a sec here. First, here’s the agreement paradigm:

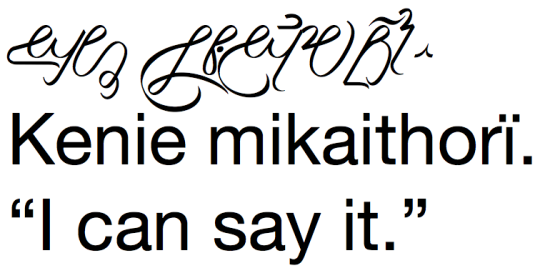

Now that you’ve got that, here are two examples (and I’ll show you the orthographic forms, too):

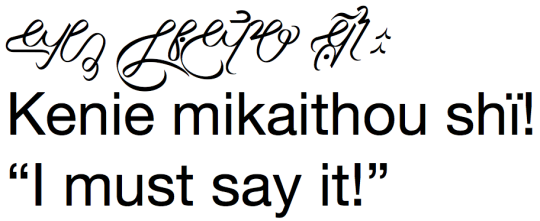

That’s Kenie mikaithorï super large, apparently. Kenie is the third person pronoun in the accusative. Mikaithorï has a third person subject, and is in the potential indicative. Now if you use the emphatic copula instead…

That’s Kenie mikaithou shï! which is “I must say it!” Now, of course there’s nothing in here anywhere that corresponds to “must”: It’s simply the interpretation. These examples show how you use the form with the agreement suffix and without.

(Also, see the geminate thingy in there? The spelling in this one is weird.)

That’s a basic intro to this thing. It was actually a pain in the butt to use, but fun to speak. All in all pretty good. Though weird.

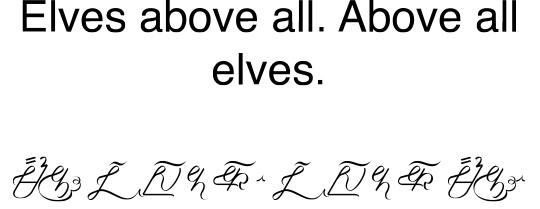

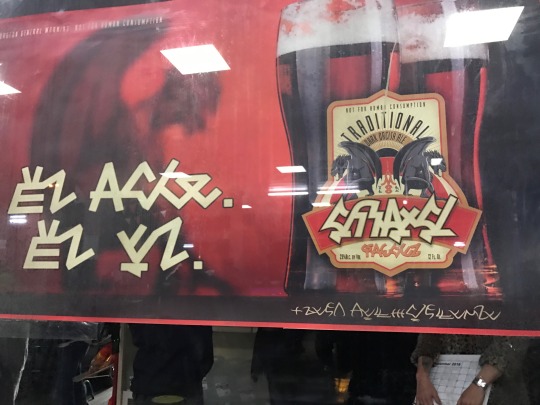

This is a piece the art department put together for Édgar Ramírez’s Kandomere to wear. I thought it looked pretty boss:

Looks pretty cool, until you realize it says the following…

And he’s one of the good Elves! lol This was one of my favorite pieces. That art department was amazing.

So that was what I was up to this time last year. Again, if you get a chance to see the movie, I hope you enjoy it! Süvorii!

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Bodzvokhan: The Orcish Language from Bright

The Orcs in Bright lived most of their existence in the Pripet Marshes. They spoke their own language, but as the Russian Empire grew, many learned to speak Russian, as well. When Russia began a campaign to exterminate the Orcs, they emigrated to many places, including the United States. The Orcish language had an old, ancient script (Vukht) which was replaced by a variant of the Cyrillic alphabet. After the emigration, the Orcs reclaimed their old writing system and began using it once again (with some modified Cyrillic letters used for sounds not present in the language when the Vukht was originally in use).

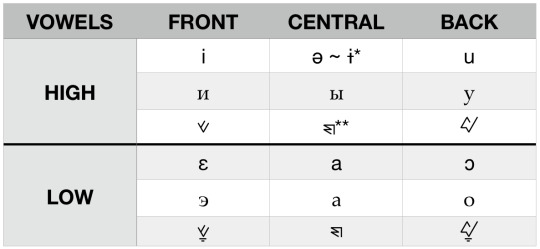

The language itself is SVO and somewhat agglutinative with minimal case marking. Phonologically, it’s highly permissive of consonant clusters, and has low-high vowel harmony. The Cyrillic writing system is, of course, alphabetic, and the Vukht is abjadic. This is a rundown of the phonemes and how they’re spelled:

These are the original six vowels of Bodzvokhan. They come in pairs like this, so every affix that takes -i with high vowels will take -e with low vowels, and vice versa. These are high and low with respect to one another, not in terms of their exact IPA definitions.

A couple of important notes here on the Vukth (ignore Cyrillic for the moment). The abjad works by placing the two lines you see in the low column below a consonant to indicate that there is an [a] vowel there. Without that, it’s assumed that there is either no vowel or [ǝ]. The original semi-vowels *j and *w are used for the vowels [i] and [u], respectively, and the low mark is used below them to indicate [ɛ] and [ɔ]. Because consonants indicate the vowel that occurs before them, the symbols for [a] and [ǝ] are never really used, and don’t differ from one another (this is also due to the fact that [ǝ] is never written at the end of a word, so usually you only see that glyph if it’s [a] at the end of a word and not obvious).

Here’s an illustrative example:

These are two different words that are nevertheless written with the same characters. The main characters are, in order, <vʀbwʣ>. In the first word, though, <v>, <b>, and <w> have the low diacritic beneath them, meaning that the vowel before them is [a]. When it occurs before <w>, the interpretation is that they combine to form [ɔ]. Thus the first word is pronounced [a.vʁaˈbɔdz], which means “I plant it”, and the second is pronounced [ǝ.vʁ(ǝ).ˈbudz], which means “I yank it”. Each of these can also take a final -a or -ǝ, respectively, but it’s usually left off (more on that later).

The Cyrillic should be uncontroversial, save using <э> rather than <е>. This is done because <е> is used elsewhere. The vowel <ы> was used basically for the “other” vowel in Orcish, and is used in Russian borrowings for the original <ы> vowel. For that reason, it can be pronounced [ɨ], but that’s usually done only by those fluent in Russian, and only in Russian borrowings. Otherwise, it’s just the symbol used for [ǝ]. Also, unlike in the Vukht, the vowels are always written.

Otherwise, the romanization is straightforwardly i, e, ��, a, u, o. In the scripts, I didn’t differentiate between [a] and [ǝ] at all (they were both spelled a), since (a) Final Draft doesn’t support <ǝ>, and (b) I was going to be on set to make sure it was always pronounced right. Plus, unless the word has all [a] or [ǝ], it’s obvious which it should be.

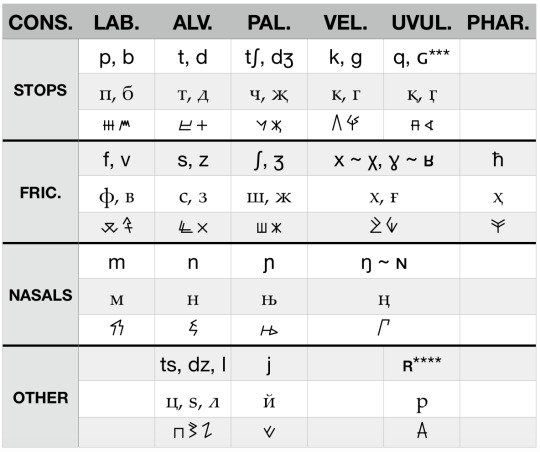

Now here are the consonants:

All of these were romanized as you can probably guess (so: ch [tʃ], j [dʒ], sh [ʃ], zh [ʒ], kh [x~χ], h [ħ]. ng [ŋ], y [j], and r [ʀ]). There are just a couple of notes to make.

There are some sounds present in the chart which have spellings in both systems that are no longer present in the language. At this stage, the phonemes and letters associated with the proto sounds *[ɢ], *[ʁ], *[ɣ], and *[ʀ] are all pronounced [ɣ~ʁ], and are all romanized as r. It’s only in the two orthographies that those sounds are still differentiated, leading to some complex spellings one has to remember.

Aside from the glyph for y [j], the entire palatal column has been borrowed from Russian, and from Cyrillic. This entire series is not native to Bodzvokhan, and is not spelled with native Vukht characters.

Those familiar with Cyrillic will doubtless have some questions about the characters chosen for the sounds not present in Russian. I went with systematicity over adhering to any specific Cyrillicization scheme, figuring that the orthography would have been created by a missionary some time in the late 1700s/early 1800s. I think it works very well as a system, but hope it works historically.

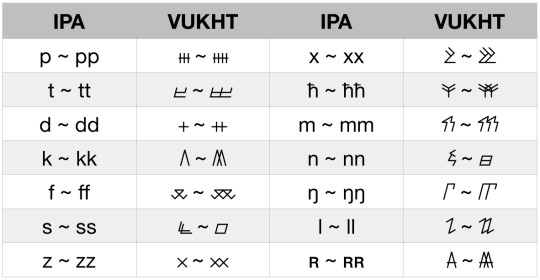

Some, but not all, of the native Vukht consonants have a special geminate form used only when the consonants appear as true geminates (so you’d use them for a theoretical word ǝnni but not inǝn). This is a list of them:

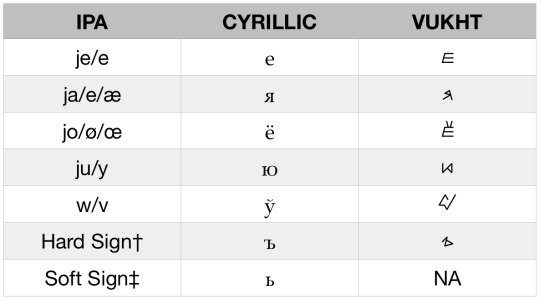

Those should be fairly self-explanatory. In addition, there are a number of Cyrillic extensions that are used for Bodzvokhan. I’ll discuss them after I show them:

Russian has an entire palatal series that’s written by having two sets of vowels. Each of these made its way to both the Cyrillic writing system and the Vukht. The sequences [jɛ] and [jɔ] actually do occur in native Bodzvokhan words, so the character are sometimes used for that, rather than the traditional sequence of the character for <j> followed by the modified character for <j> or <w>. Old *[jɔ], though, eventually developed into modern [œ], and so now the new character <ё> is used for that vowel. In parallel, the character <ю> is also used for new [y]. (So now Bodzvokhan has an eight vowel system.) Other characters are used variously in borrowings, with the old Cyrillic character <я> used now in English borrowings where [æ] is wanted.

The old Cyrillic soft sign <ь> was only used in the Cyrillic writing system for Bodzvokhan, and only in borrowings—and even then, inconsistently. The hard sign <ъ>, though, developed a life of its own. Old sequences of stops followed by *[ʀ] have evolved to become hard consonants—probably velarized. Or something like that. As a way of marking these, the hard sign is used following stop consonants. There are no longer any sequences spelled with a stop glyph followed by the glyph for r in either the Cyrillic version or the Vukht. (In addition, velars became uvulars before r.)

Anyway, that’s more or less the phonology. Stress is on the second-to-last syllable of the root.

I see this is way longer than expected. lol I’ll show you some minimal grammar stuff, then.

Nouns distinguish singular and plural, as well as nominative and genitive. Here are some examples:

NOM. SG.: dri “stone”; qǝs “summit”; dǝzhn “language”

NOM. PL.: drif “stones”; qǝsif “summits”; dǝzhnivǝ “languages”

GEN. SG.: drin “stone’s”; qǝsǝn “summit’s”; dǝzhnǝn “language’s”

GEN. PL.: drim “stones’”; qǝsim “summits’”; dǝzhnivin “languages’”

If you take those same three types of words (ends in a vowel; ends in a consonant; ends in a consonant cluster) and switch out the vowels with low vowels, then you get low vowel suffixes. Thus, with örq “orc”, you get örqeva, örqan, and örqeven.

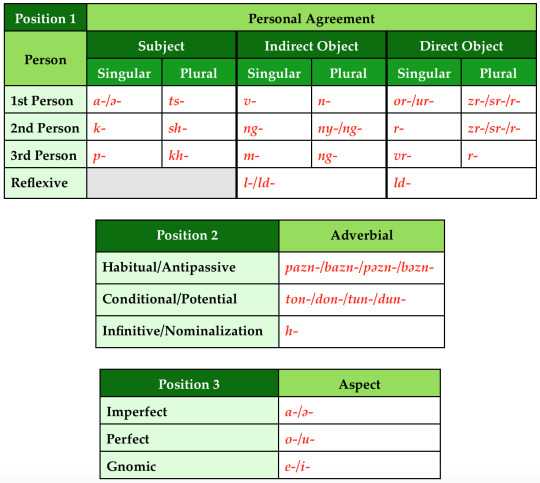

Verbs agree with their subjects, direct objects, and indirect objects, and also mark aspects, polarity, and a few voices. I’m actually going to be super lazy and put up table images, because why not this is huge anyway. lol

These are all things that come before the root. So if nǝd is “give”, ǝmvrǝnǝd is “I give it to [him/her]”, kvǝvrunǝd is “You gave it to me” (can’t have a geminate [v] like that, so the [ǝ] breaks it up), khngrbǝzninǝd is “They always give them to you”, and khngrbǝznunǝd “They always used to give them to you”, etc. The nominalization can be used to make regular verbal nouns, but also complex infinitives, like ǝngvrhunǝd “for me to have given it to you”.

There are two types of suffixes that can come after the verb root:

The position 4 suffixes are optional (used only when needed), and the affirmative polarity suffixes are generally not use save for emphasis at this stage (which is why many verbs end with the verb root, in practical use).

The third person agreement prefixes are also used to form agentive nouns. Thus, the verb form pegazdasa, which means “s/he works regularly”, is also the noun to mean “worker”. (In fact, as a noun, the final -a will always be on there, whereas for the verb most of the time it will not be.) These nouns, then, don’t have the usual case frame, as their “plurals” are actually just plural verb forms. Thus:

NOM. SG.: pegazdasa “worker”

NOM. PL.: khegazdasa “workers”

GEN. SG.: pegazdasan “worker’s”

GEN. PL.: khegazdasan “workers’”

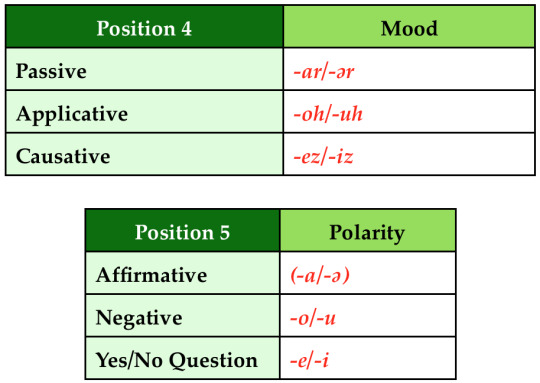

That gives you some of the major points of the Bodzvokhan language. There are adjectives, they come before the noun, and they agree in case and number. There are lots of borrowings from Russian, and some from English. Here’s probably my favorite sign that the art department came up with:

Öl Ruf. Öl El. “Dark Times. Dark Ale.” lol The ale is called Omarzo Gǝrrul “Ugly Gargoyle”. And that word mark for the word omarzo, “ugly”… Just brilliant. You know, I first came up with the Cyrillic script for Orcish, because, based on my understanding of what I discussed with David Ayer, that was the only one that was going to be used. But then he said he wanted another script—more angular and crude-looking—so I came up with the idea of the old script that was reclaimed. I didn’t like the look of it at first, but when I saw what they did with that word mark, I was like, “All right. This works. This is good.” Those art department folk are wizards. There was a guy there that had an Ugly Gargoyle ale shirt with that on it, and I’ve never coveted anything so bad…

Anyway, that’s an intro to the Orcish language, Bodzvokhan. Hope you like it! Up next is Elvish!

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

This

Are there any particularly interesting things that can be done with the copula in a conlang?

I’m going to put this in bold and caps so you know how serious I am when I say this: THERE IS NOTHING YOU CAN DO WITH A COPULA THAT WILL NOT BE INTERESTING. (Hope the double negative doesn’t throw people there.) There is no copula in any language on Earth where you just say, “Eh. It’s not very interesting.” I defy you to find one. Whether it’s a set of irregular conjugations, or rules about what tenses it can and can’t be used, or a division by the type of things it equates, or its use as an auxiliary, or a combination of many of these things are even wilder other things, copulas are always interesting. Probably the only language I can think of that has a boring copula is Esperanto, but it is slavishly devoted to regularity (or what it considers regularity), and it tries to strip of all its fanciness. (Though it is the only “transitive” verb that doesn’t require an -n for its “object”, and it can be used for compound tenses, which is something no other verb can do. So I guess it’s even interesting there, too.)

If your copula is not interesting, it’s probably because you copied or assumed something from the copula of your own language that you don’t think of as interesting which is actually interesting.

Copulas, I tell ya… They’ll do it.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

@fezraptor I now present, Deinocheirus mirificus, Trevorrowised!

Not how the distinctive giant arms and claws of Deinocheirus are replaced with slightly long Generic Theropod Arms, with pronated wrists no less! The unique and bizarre head was also way too interesting, so we switched it out with a Generic Theropod Head, with just the slightest hint of a toothless beak. The skin is also shrunk down right onto the bones and muscles so that it looks strong and dangerous.

The body is a beautiful dull beige, and the sail has just a touch of red. After all, it’s obviously a display structure. All of these artistic changes ensure that our creature designs remain true to the look and feel of Jurassic Park and the Stan Winston style.

What’s that? It’s not accurate you say? We’re being faithful to the spirit of the original Jurassic Park that people love! After all, it’s not like Jurassic Park was built on showcasing a new and exciting portrayal of dinosaurs to the general public, with thoughtful and careful designs that were accurate to the science at the time (with a few exceptions)!

Oh wait, that’s exactly what Jurassic Park was. Nvm then.

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Momma Oryctrodromeus stays in the burrow with her babies while Papa goes outside to tell the stinky mammal to get off their lawn.

Read more about them here

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Momma Oryctrodromeus stays in the burrow with her babies while Papa goes outside to tell the stinky mammal to get off their lawn.

Read more about them here

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Lexember

#lexember

Teï Taviheï. Teï/u pemu [ˈtej/ ˈu ˈpu.mu] "Leg/foot"

Kôlo. Jöwem [jə.ˈwem] "Leg"

Bôrugû. Nolla [ˈnol.la] "Leg"

#conlang

1 note

·

View note