my name is pau and i talk here about all the different things i wanted to write. this is kind of my headspace.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

The stories we tell ourselves

27 February 2021. It seems like the lockdown sort of made me miss a certain person that became an important presence in my life for a while.

Four, five years after the fact, before every dreamless slumber, my thoughts never fail to drift to Blue. At one point I believed that my wishes might have the power to bring him back and continue where we left off, no matter how long that takes as if this grieving period has an immeasurable expiration date that will magically kick off with a happy ending. Looking back on a rather strange time of my life, I always try to remember who I was, what I looked like, how I took care of myself and my feelings, and the very desires that were left unsaid but immensely obvious in our actions. The majority of his presence – his shaky arrogance, false projections, frustrations, and debilitating self-doubt – was nearly impossible to soothe so we turned almost everything in jest until we couldn't distinguish hurt from laughter.

But in rare moments of tenderness, Blue was thoughtful, encouraging, and endearingly (sometimes painfully) opinionated about every little thing. When we had our first serious conversation over chat, it went on for hours and hours than I can count. Little did I know that it would be our thing for months to come: he talked about all the bands that saved his life, the places in Japan he was dying to visit, our shared love for musicians named Paul, as well as a mutual admiration for John Cusack. I told him that Say Anything is one of my all-time favorites and, to this day, I'm still wishing for a love like what Lloyd and Diane had.

"Have you seen High Fidelity? Akong-ako si John Cusack don," he said. "Although, Jack Black also had some moments."

I told him I was planning to because I was finishing reading the book at the time. “Keep this book away from your girlfriend – it contains too many of your secrets to let it fall into the wrong hands,” one of the most prominent praises for the book says. It read to me like a red flag as Blue and I entered into a month of seeing each other.

I knew what kind of person Rob Gordon was. He was ruminating, insecure, selfish, and lonely. He was terrible with women. Cusack translated this on screen very, very well. His charming man as Lloyd was nowhere to be found even with Cusack’s regular joe good looks. But then again, I’ve always felt compelled to love complex (read: difficult) people.

Blue glorified this character, as well as the movie, to death. He’d come over to my place a week later to watch it with him.

"Sabi ko sayo e, guys like us still stand a chance," he said as the credits rolled, looping his arm around my middle, stopping me so we could lay some more. It was a sunny afternoon on a weekday and I remember taking him to my bedroom to smoke because I didn't want the smell to give away the fact that I wasn't alone. Boyfriends, or any form of male company really, were an unspoken restriction in our make-shift compound.

I watched while I waited for him to finish the last drag off of his cigarette before walking up towards him by the window. I just wanted to be close to him – to see if he could let me in. It was still unfathomable to me that I invited a boy in my room, let alone one that I actually have real attraction for and seems to feel the same way. He sealed our closeness as his tall frame leaned on mine until our lips met in an innocent but lingering kiss.

Soon these secret meetings became uncomfortable. From going to each other's houses, we would opt to stay at motels with no lunch nor dinner dates prior. I was starting to worry. But more than anything I was sad because I had already altered my brain to allow myself to be seen, warts and all. I opened up my heart and I was ready to jump from infatuation to real love. Maybe I was already there.

Our memories are imperfect and often glossed over, and when I trace them back to those five, six months of... whatever, I often catch myself wondering if they were ever real. Though, one thing is for sure: I was aware of how I felt.

To quote Tavi Gevinson, “I try to remember that what I really want is not to go back, but what I have now: the image, the memory.”

We were anchored in troubled waters and the angle was off right from the beginning. I already felt small compared to him. Five years ago I would've claimed that no other guy could ever make me feel how he made me feel. That, my affections were a gift he so deserved that I would be the luckiest person on earth had he acknowledged them, if not returned. I always felt reciprocation was already too much to ask – that I would be more than fine with settling for the bare minimum. As I said, I already felt small next to him.

Today, like many days passed, I wish I reacted differently and cherished those moments of openness because I knew he was maybe reaching out for someone to listen. I always felt he just didn't like being pitied because of his stubborn pride. Even so, I won't ever trade those bits of perpetual bliss talking from our beds for anything. I want to believe that I truly connected with someone in those brief months just when I thought my life was getting stranger and turning into something I could no longer control.

Those of us who were born with a growing solitude and harbored an uncompromised independence have a complicated relationship with intimacy. I don't dislike vulnerability even if it's with the wrong friends and romantic potentials because I'm not an inverted snob. But then again, intimacy is a fickle thing to betray and plays a key part in abandonment. I'm still going through establishing the right set of boundaries with everyone I meet and I already know; I just have to remind myself time and time again that they don't have to be infinite.

0 notes

Quote

He will love this music to death. In a few more years, he’ll snort at its sentiment and mock its stirring progressions. Once you’ve loved like that, the only safe haven is resentment.

Richard Powers, Orfeo (via quotespile)

162 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hong Kong, August 2019

Three weeks from now on this month last year, I would find myself on a spontaneous five-day trip to Hong Kong. I remember telling nobody that I’d be away for a few days except for one or two people. Not even my sisters who I live with would know about it until the weekend before I leave for my flight. I also told my colleagues, including my managers, that I would be resting and regrouping at home upon signing my leave.

This is not the first time I sought refuge far away when things are becoming too much. It’s a pattern, I find, that after I’m faced with a difficult task whether it be at work or my personal life, I let myself blend in obscurity instead of opening up to a friend or a close family member. It’s escapist behavior, I guess–there’s no other way but to slip down in a rabbit hole until I feel okay to crawl back out again. Although, over the course of a year or two, I’d like to think that I’ve shown some vulnerability to a trusted few despite my nagging guilt and shame of having done so. I’m still finding the balance between what’s mine to cherish alone and what’s mine to nurture with others.

21 August 2019. Kubrick Cafe in Yau Ma Tei. This is a nice little corner attached to the rusty Broadway Cinematheque on Public Square st. I had dinner here after spending most of the day out and about. Not only is this a cafe + bookstore, Kubrick is also a small movie house featuring independent releases and mainstream Hollywood flicks. I believe Parasite was showing at the time of my visit.

Remembering this trip makes me feel good about where I am now. It was around this time I was feeling disconnected at work, including the friendships I formed and even the small victories we earned as a team like getting praised by our supervisors and being given challenging projects. My personal productivity and pursuits suffered greatly because I would be catching up on sleep as soon as the weekend hits. I didn’t know what to do with myself; I was reluctant to change anything because I was earning an ideal amount just enough to cover everything I needed. On top of this, I was also dating a guy with an emotional depth of a teaspoon when he was supposed to be my silver lining–he was really sweet and affectionate to me but I couldn’t get through to him… for some reason. Later on, I would start talking to a former flame in hopes of fulfilling this gap and stumbling somewhere meaningful.

22 August 2019. On some street in Quarry Bay. I was lost and finding my way back to the nearest MTR station when I took this shot.

All of this–this kind of downward spiral really slaps you in the face and here I am still mourning about what could have been. It’s humbling but it’s a painful experience to come back from. What is it that we’re so afraid of that we gravitate towards the things we end up hating ourselves for?

22 August 2019. Quarry Bay Park Football Pitch. I wish we had vast, public spaces like this in Manila.

I’m rambling now but if there’s one thing I learned from this trip, it’s that it’s important to work on something you truly care about. I strongly identify–or rather try my hardest to embody–with and what my job title asks of me that I lose myself in the process. For many years, I’ve found myself unable to separate my life and work. I don’t do well with authority despite succumbing to (constructive) criticism from the ground up. At best, I take their advice, build a habit around it, but still, I fall short of expectations. What am I doing wrong? I’m tired of being in limbo but at the same time, I’m still intensely at odds with where I should be.

0 notes

Photo

The naked truth

Photos shown are not mine. For some unknown reason, I lost the images accompanying this preliminary requirement I submitted for our Features class.

He strips. He introduces himself briefly in a heavy Mediterranean accent; no longer than a line or two. There is something in the way his eyes shift from every person in the room to another–his gaze so intense as if he was scorching every detail.

He is built like a Greek God, from his accentuated shoulders, firm and smooth chest, to the lean muscles of his arms and legs perfected by athleticism, molded beautifully and crafted delicately in white marble as if by Michelangelo himself. His face resembles innocence as reiterated by his little boy haircut, a princely manner that is distinct especially in the way that he speaks–pleasant yet controlled.

The incandescent lights of the small space cast an alluring angle invoking eroticism, along with the makeshift black curtains behind him, and the grey walls almost claustrophobic and the deep shade of red of the floor where his bare feet are standing on. He becomes quiet as he starts to breathe slowly at first. The inhales and exhales gradually exaggerate. Then, the room is suddenly warm.

When a choreographer like Bruno Isaković ventures into a performance that has a strong relationship with nudity, he configures the audience’s anticipation of a transformation that he, the artist, leads–questioning audience-artist relational dynamic or perhaps the distance that creates confusion between the two. In “Denuded”, a 30-minute work performed on Wednesday at Catch 272 in Quezon City, Bruno engages in a similar dialog, responding to the specificity of a work that was originally conceived for the theater as he omits the idea of classical staging and instead uses his body in the middle of the dance hall–exhibiting sculptural aspects of performance and capabilities of communication with the audience.

At the start of the act he is immobile, then accelerates into small body movements like expanding his chest, causing his shoulders to rise, his breathing becomes shallow as he inflates and deflates. Soon, he explodes into different motions as he twists and turns; his body is arching, swiveling, twisting, crippling–the flexing of his muscles is visible and tense as if gravity is compelling him further to mount on the surface.

The changes in lighting is synonymous to the heavy intakes of his breathing–from one incandescent to another they go until a small spotlight looms around Bruno’s sensuous body parts, emphasizing every tiny detail that tests every spectator’s judgment. The protruding erection goes unnoticed. Looking down, he’s made himself a pool of water beneath his feet; he is shimmering with sweat.

He maintains eye contact with those who are watching him change pace in his movements, as each sight becomes more intense to sensual and graceful. Nearing the end, he slow dances as if a pair of skilled invisible hands is molding him into shape and then he leans back like he’s falling and stands up again after being in a trance as the lights came back up.

“It’s surprising to see that there is a conscious tension of not being common with seeing a naked body. Like, if you would just walk around naked, it’s like our eroticism would only depend on nudity,” says Isaković, defining eroticism or any form of performance is when it deeply touches physical transformation and the automatic attribution of its meaning to what we at a given moment are able to see, recognize, and experience. “We make things so hidden that when we see a dick, immediately we think of sex.”

Isaković may denounce taboos in his work, and instead, as a performer, he mutates physical expressions and stage presence that goes far beyond the purely physical movement–equaling them to that of the relationship between the secular and the spiritual.

True, what he did may be erotically exhibited as it was sexual in sight, but importantly the feedback loop of communication between the artist and the audience is channeled through the significant transformations of the artist’s body. The journey which the artist tries to lead his spectators repeatedly questions their understanding of a piece.

He remarked also that there is a difference if Denuded is performed by a female because a naked woman summons different connotations, like “the male gaze”.

“You get more different things that a female body produces. In female version, its performed by one real extra-ordinary girl. She’s super thin, almost like anorexic, and pale with natural red hair. She looks like some kind of goddess. She’s amazing,” he says, describing Ana Vnucec, a fellow dancer and the female counterpart of Isaković in Denuded. Despite of her fragile frame, he recounts that she is adventurous in her transformations, like a fierce lioness.

However, the most difficult of tension is not even the sexual kind, according to Isaković, but the social one. He professes that performances like Denuded enrages social stigma, especially when he performed the act in his home country, Croatia.

“It’s not so much that they were tense because of the nudity, I mean the people of Croatia are very genuine, but to them that was pure exhibition. Like, ‘why do you do that?’ or ‘why do we need to see that shit?’” he recalls, ashamed of the conflict of allowing the artist to show everything, to go past what he’s trying to prove, and see what it makes spectators feel.

Isaković bethinks that the strenuous history of Croatia also plays in its aversion towards subjectivity such as art.

“We’ve been through socialism and communism for a very, very long time. I guess the people are just not used to developing their own sense of individualism. That border is just so strong that they couldn’t go beyond it,” he says.

Denuded is a fitting response to the current preoccupation of visual art spaces with dance and embodied practices, and vice versa. But when asked if he intends to deliver a message through this work, he refuses to give one.

“For me, it’s interesting to see what kind of reaction it creates. If it’s about transformation, then that it’s not a complete question,” he says. “It’s about making a connection, how two people relate to each other with their breaths and sending tensions to one another and what does that create.”

Words by Paulin Atienza

Date written: 2013

Photo credits: Ahmad Odeh on Unsplash

0 notes

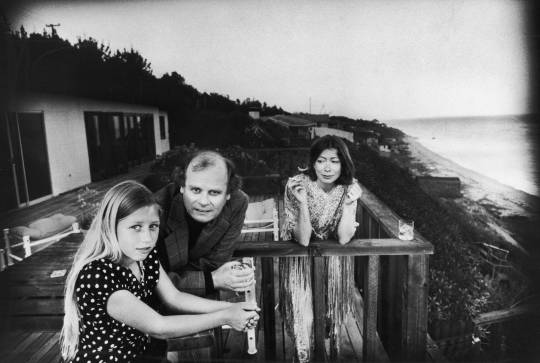

Photo

What Joan Didion taught me about grief

It has become difficult for me to get back on the habit of enjoying books like I did when college was my playground–trippy and void of responsibilities–or at least that’s how I remember it. Being on the second month of the job search has made me braindead, and having no money to go out left me nowhere else to stay but in the (dis)comfort of my home. With little to no recreation to kill time, I bought myself a ticket to the most frustrating year of my life yet.

I finally turned back to reading after a late evening conversation with my great friend back in college. I met Tox as a classmate in freshman year and we’ve known each other since. He would always introduce me as his first best friend, dubbing me as the one who got him into The Beatles to his friends and other acquaintances at UST. He’s very much involved in theater and identifies himself a thespian. But to me he’s a writer with an eloquent taste for words.

“Life changes in the ordinary instant,” he said quoting Joan Didion a third time in the telling of the tragedy of a late childhood friend swallowed in the ocean on a gloomy day. He said he was a belligerent character as most young children we’ve known growing up.

To his naivety, consumed with an appetite for danger, he had swam on his own far out the sea despite knowing that a great tide was approaching as told by the two cronies he brought along with him. He didn’t listen. The inevitable happened later to that young boy; the “eternal dark” after the ordinary instant at the beach, of what was supposed to be an innocent, playful visit at the filming location of a famous soap opera.

His mother, devastated but have chosen not to impart guilt to the two other boys, could not have been anymore candid about the unfortunate event as she pleaded with the rescuers to keep looking for her son’s body. Whether she was ready or not to face this turning point, we never knew.

Life changes in the ordinary instant. We cannot cling to the past forever yet it lingers on us as we go in the future.

A well-documented experience on grief is the subject of The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion. Just like the mother’s grieving of her son, Didion also faced with the same fate when her husband, writer John Gregory Dunne, died of a heart attack at the end of 2003. Shocked to the bone to accept things as they are, her grieving was a turning point she had chosen to avoid, believing that once clarity takes its place, her memories of John will be something that’s already passed.

It seemed that Didion cheated on acceptance as she did not want to be reminded that she had to move on with her life without John. Evidenced by her meticulous search and understanding of the fatal heart attack, she lived as though hanging by a thread with the tiniest bit of hope she was denied of.

The denial would go on even after the book had been closed.

I may not know what grief is nor have I caught myself in the state of loss of an immediate family member, but the empty days Didion had to endure in the depths of her newfound senescence is all but stillness. The stillness is an unconscious choice made due to a shock–a beautiful flaw that, as humans, we must rejoice in for we are genetically made to love and be compassionate.

What doesn’t kill us makes us stronger and Didion exercised a certain kind of controlled pain in times we mourn. The Year of Magical Thinking is making sense of what’s no longer there, or that letting go would be synonymous to forgetting–a means to an end.

Words by Paulin Atienza

Date written: 2015

Photo credits: Tampa Bay Times, Vox Media

0 notes

Photo

Moving through life is hard

I’ve been spending the last few weeks doing house work like it’s a full-time job. There’s still so much to be improved and I am nowhere near what I have envisioned for this house to feel warm and cozy. I don’t have big plans for 2021 except to earn so I can finally move into a place of my own by next year. But as the eldest of three with parental responsibilities, I want to leave this house with tenderness and balance.

I became a (pseudo) homemaker by circumstance. My mornings stretch to mid-afternoons on most days doing what mothers have done for us when we were little: cleaning the living room spotless, refilling the pitchers, putting the dishes back in their respective drawers, taking out the trash, and feeding the dog before rewarding myself with coffee (or tea).

It’s not exactly what I pictured 2020 to be; the original plan was to go on three week-long overseas trips solo:

☑ Taipei, Taiwan (January)

☐ Beijing, China (June or July)

☐ Seoul, South Korea (October)

I really miss traveling. I’m sharing photos from my first and last trip of the year. Yehliu Park was a dream, which only solidifies my desire to live in a home surrounded by nature.

My life is good–even better now–but I still can’t shake this sleeplessness off of my system. I become far more restless at the thought that I have to go to bed every night for a peaceful sleep that I no longer remember what it feels like. The pointless quest of the rat race truly turned me into something I didn’t want to be, a chaser of the urban working life, settler of stability, a sellout, what have you, all of this boils down to me becoming an automated feature. Reaching a tipping point, I needed to step back after a good five years of running on empty.

Last April, at the dawn of a sobering generation and opening doors embracing the ordinariness of living inside, I never imagined that I would be included in a company’s retrenchment program that effectively let go a sea of hardworking people in batches for the next few months. Loose ends were written all over this sudden move as I keep my eyes peeled for my well-performing colleagues local and overseas face the same fate: their farewell, gratitude-laden messages in hopes of immediately landing a new, shiny opportunity occupy my feed. While knowing that I’m not alone in this uncertainty surely soothes the pain of my unrealized ambitions, I can’t help but feel I’m back to square one again, only with a stronger backbone and a more controlled direction that I wish I knew many years ago. I also wish I didn’t put all my efforts and prospects in one place to compensate for my lack of structure in life.

But we live and let live. In my case, I learned the hard way that we should not glorify the pain behind long hours striving for excellence and actually begin doing things differently.

0 notes

Photo

I am now a dog mother

My day is just starting and I have two deadlines waiting for me this week. While I’m still getting used to this work from home setup, although indefinitely, I’m taking this moment to improve my time management and organization skills. I came from a 9-5 that extended to countless midnights spent at the office and I’ve vowed that I will never go through something like that again.

Lockdown living is quite a blessing in disguise. I live and work with a dog now and to say that things at home are looking well and great would be an understatement. My best friend got him for me two days after Christmas and I brought him home last March. He goes by Kazoo and he’s the sweetest.

It was not planned nor did I see I would ever own a pet, let alone a three month old puppy, in my otherwise busy schedule (I’m freeing up my life for more time spent at home). I’ve tried my hand in adopting one of the many stray cats roaming in our block a couple of years ago. She was a free-spirit (as most cats are) and had different names given to her by neighborhood folks but in our household she will always be Malkmus. She left us forever with her litter of kittens, just when they turned two months old. I’m still grieving over that scam to this day.

Kazoo has a serious bout of separation anxiety. He spent his first day in our home by himself unleashed so he can get used to his new surroundings, only left with a meal and water to drink good enough for 12 hours or more. Probably not the best dog parenting tip but I only had a few people to call for advice and this was the most feasible thing we could do. Little did we know we were doing more harm than good because for the next nine days or so, we would find Kazoo in the care of our landlord upon arriving home from the office. Kuya Manny is a stay-at-home dad of two boys around the same age as me (I’m 27 now) and has lived with dogs for most of our lease period here. He would always say that Kazoo cries every day as soon as we leave for work and he couldn’t help but bring him to their house to play with his pups just so he wouldn’t feel lonely. No wonder Kazoo turned out to be such a friendly and approachable dog to other puppies on our daily walk.

Since then late nights at home are welcomed with over-the-top greetings, chin-licking, and intense sniffing from our pooch, as if trying to figure out where we’ve been during the day.

All of this happened two weeks before lockdown was announced in Metro Manila. I had my fair share of puppy blues as a pup’s first few months are often the hardest that I actually thought I would eventually return him after a couple of weeks because the responsibility was overwhelming. Maybe it was meant to be that I lost my job to reevaluate my decisions, how much attention, energy, and time I should give work, and the nearing dysfunctionality of the family situation at home.

Nowadays I feel content and happy. It’s not perfect but I’m beyond thankful that I’m no longer in a dark place. Kazoo has no idea how much he has done for me than I did for him.

0 notes

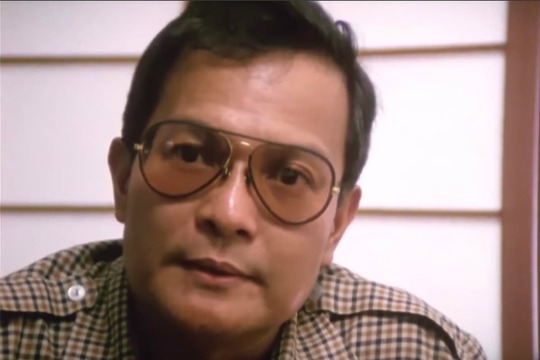

Photo

Paradise Unfound: The Brilliance of Lino Brocka’s ‘‘Maynila’’

Lino Brocka’s Maynila sa Mga Kuko ng Liwanag (1975) is arguably the most complicated work in Philippine cinema. Translated as “Manila in the Claws of Neon” and “Manila: In the Claws of Darkness” to foreign audiences, the film made it in some international critics’ lists as one of the most important films ever made. The indecision in providing a more accurate translation sheds light to the uncertainty of the film’s characters, their fates bounded by Manila’s luminescence and darkness–mystified by its pleasures and dangers as they venture on what was supposedly a hopeful journey.

Bembol Roco stars as Julio Madiaga, a young fisherman from the country who travels to Manila in search for his lover, Ligaya Paraiso, portrayed by Hilda Koronel. A certain Mrs. Cruz whisked Ligaya away to the city in hopes of getting a stable job and education there but was likely prostituted and slaved to a Chinese merchant. Julio finds himself in the heart of society’s outsiders and misfits: slums, callboys, prostitutes and undocumented blue-collar workers who make up Manila’s underclass; like Julio, they’re mapping out their futures in the city of bright lights.

However, Manila, despite of what country folks make it out to be, is a long way from being the land of opportunities. For Brocka and his characters, there is an understated frustration and resentment glossed over by the city’s bright neon lights. However, its ugly side will soon possess Julio and his cohorts to turn to desperate measures. Julio learns that in order to survive in the dog-eat-dog society, he lands his first job at a construction site where he makes two pesos and fifty cents a day but four pesos according to the documents. Nearing the end of the construction, Julio and a few others get fired simply because they are no longer needed. Soon after, he finds himself working as a male prostitute, which unmistakably pays better than doing construction labor though it takes a much greater sacrifice to come to terms with.

Along his journey, Julio meets a few good people and is getting closer to his goal of finding Ligaya. But he has also shown fits of frustration in certain conditions–shaken by a bitter mix of pain and emotions; Brocka perfectly captures Julio’s indifference until it disorders to a kind of pitiful rage, hinting at his tragedy to accept such fate. Julio is left only with a little glimmer of hope that soon disappears in the darkness that in the end he comes face to face with death.

An uninventive mimicry of the Greek Orpheus’ journey to Hades’ Underworld to rescue his wife, Underworld can be likened to Manila–bathed in neon lights, a metaphor for hope, but beneath the dazzle is a disguised injustice within its towering buildings and vigorous commercial establishments–a modern metropolis. Orpheus is Julio, who is subjected to the test of Manila’s reality where life is tragic, dreams are repressed, and in spite of great sacrifices, one is forever trapped in its torment.

Maynila, perhaps Lino Brocka’s most powerful film, is the every archetypal tragic plot that transformed from imagination to a world with human shape and meaning. Northrop Frye, one of the most prominent modern literary critics, poses that the art of literature is formulaic because every story has a signatory archetype, such as the hero’s quest.

For Brocka and his characters, there is an understated frustration and resentment glossed over by the city’s bright neon lights. However, its ugly side will soon possess Julio and his cohorts to turn to desperate measures.

An uninventive mimicry of the Greek Orpheus’ journey to Hades’ Underworld to rescue his wife, the Underworld can be likened to Manila–bathed in neon lights -- a metaphor for hope. But beneath the dazzle is a disguised injustice within its towering buildings and vigorous commercial establishments–a modern metropolis. Orpheus is Julio, who is subjected to the test of Manila’s reality where life is tragic, dreams are repressed, and in spite of great sacrifices, one is forever trapped in its torment.

Maynila, perhaps Lino Brocka’s most powerful film, is the every archetypal tragic plot that transformed from imagination to a world with human shape and meaning. Northrop Frye, one of the most prominent modern literary critics, poses that the art of literature is formulaic because every story has a signatory archetype, such as the hero’s quest.

In his first book, a close reading on William Blake titled “Fearful Symmetry,” he describes that culture and civilization are derived from imagination, which he defines as a “creative force of the mind.” In the movie, audiences are drawn to the reality of Manila’s culture and society where the central character, Julio, a young man from the province in hopes of making a living in the city, is an archetype that begins with a “recurrent image, plot, and pattern”–a retelling to take on a “universal quality.” In Frye’s “Anatomy of Criticism”, the word “archetype” means “beginning pattern” that audiences can relate to because they are who are being represented by the characters. Characters are made human, Frye argues with a Jungian concept that “part of what makes us human is an “unconscious inhabited by shared memories, desires, impulses, images, and ideas” that are distinct in every archetype.

But Julio is nothing like a hero; he is indifferent, then passive-aggressive. Brocka shies away in displaying Julio’s violence and instead captures his innocence until his death. Brocka finds stupidity, not depth, in Manila’s commitment to corruption that it plagues those who dwell in it. Given Julio’s innocence, he is blinded by the neon lights of Manila, thus believing that there must be a better life to earn in it but instead, he becomes the central victim of the city’s deceit. Sometimes heroes are not meant to triumph in the end–what with Julio’s character growth, murder as his last resort that was sparked firstly by the death of Ligaya; secondly, due to his resentment that he can no longer suppress.

...audiences are drawn to the reality of Manila’s culture and society where the central character, Julio, a young man from the province in hopes of making a living in the city, is an archetype that begins with a “recurrent image, plot, and pattern”–a retelling to take on a “universal quality.”

The film carries a hard-hitting truth: the rational response to poverty is violence. It’s a prime vision of what Frye calls the “human tragedy” in which the “human world is tyranny or anarchy, an individual or isolated man, the deserted or betrayed hero” that follows the “human pattern.” No one is redeemed, but that’s what evokes a sensation.

Words by Paulin Atienza

Date written: 2013

Photo credits: The Criterion Collection, Asian Film Archive, Letterboxd, The Manila Times

1 note

·

View note