Text

Next Generation’s Best | Masterpost

An essay on generational talents, gender, and the NHL in six parts.

One | Two | Three | Interlude | Four | Five

available to read on ao3 here

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

bonus: even the dogs are besties!

845 notes

·

View notes

Text

"A long time ago, the NHL was created. This has made a lot of people very angry and is widely regarded as a bad move."

Read the first installment of @sergeifyodorov's history of the #NHL here.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

a suzufield/1422 primer

click the link to view the presentation! this is my humble attempt at a primer for these guys cause like... look at them. anyway my messages are open for anything you think i'm missing or if you'd like extra musings about them, or more individual characterization, bc i could talk about them all day <3

gonna plug the habsfic server, if you have suddenly found a new interest in these two

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

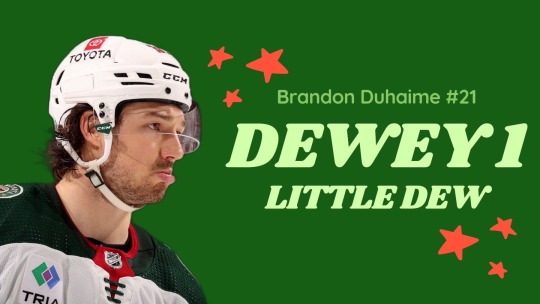

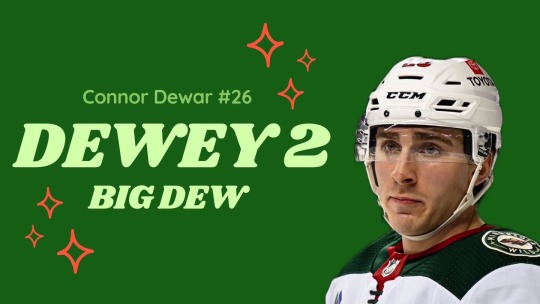

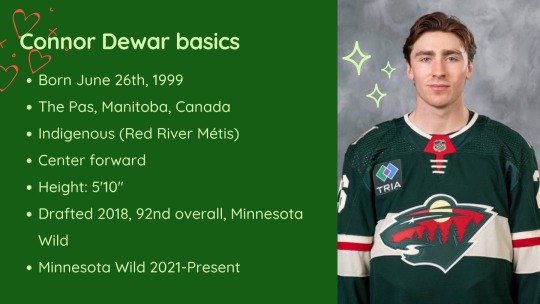

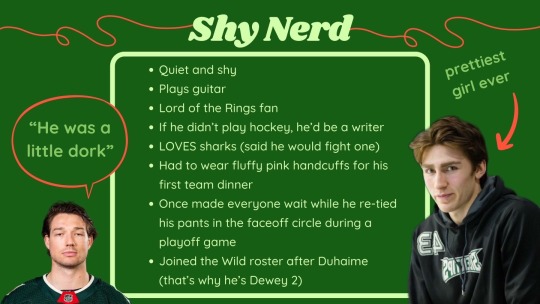

so, you keep hearing about two idiot 4th liners on the Minnesota Wild that have the same name, but know nothing about them?

well, let me help you

Still want to know more? Further reading below! (AKA iconic dewey posts)

Videos

juggling masters

waiter!

Brandon eats paper

Rookie prank

gus bus

GIF sets

Brandon rookie lap + goal

Connor is a nerd

pathetic Brandon

intimate celly

shark

Misc

neither can cook

THEYRE HOT AND CANT FIGHT

dumb + confident

goalies

worst picture of the deweys ever

I have never made a primer before I hope you enjoyed !!

569 notes

·

View notes

Text

Evgeni Malkin and the chip on his shoulder that led him to greatness.

Jan 7, 2023

Evgeni Malkin learned some hard lessons well before he became an NHL superstar. He learned quite a few after becoming one, too.

Malkin, one of the greatest Russian-born players ever, was not a must-see prodigy from one of his country’s hotbeds for talent. Though he took to the sport at a young age, he went relatively unnoticed abroad until his 2004 draft-eligible year — and even then, despite ultimately becoming the second player selected in that draft, he was clearly behind longtime rival Alexander Ovechkin.

“We liked what we knew of him,” said Craig Patrick, the former Pittsburgh Penguins general manager who selected Malkin after the Washington Capitals took Ovechkin in 2004. “We’d done our homework on Malkin, and I even told someone that he might end up being the best player in that draft. I believed it, with his size and skill, and I always liked the idea of a centerman being somebody you built around.

“But even while we were scouting him, you had the idea that a lot of teams were unsure about Malkin,” Patrick said. “You looked at him and liked his size. You watched him play, and he dominated. But I remember thinking we thought we had a franchise player if he fell to us, and that wasn’t a consensus opinion.”

It didn’t matter what other NHL clubs thought of Malkin. With Ovechkin, a white-hot hyped prospect being a lock at No. 1, Patrick wasn’t about to let a 6-foot-3, 190-plus-pound center with a playmaker’s vision and a goal-scorer’s touch get past the Penguins.

“I’m lucky,” said Malkin, the No. 26 player on The Athletic’s list of the top 100 players in post-1967 expansion NHL history. “Pittsburgh is the perfect place for me.”

Pittsburgh and Malkin’s hometown of Magnitogorsk share an industrial heritage and blue-collar DNA. Even Pittsburgh’s usually gray skies and brown waterways reminded him of home. That the Penguins were owned by Mario Lemieux, a star whose brightness reached even Magnitogorsk, only endeared his future club more to Malkin.

If only he could get to Pittsburgh.

And that’s the first lesson of Malkin’s story: To get what you want, you’ve got to take control.

Malkin doesn’t much care to talk about the details surrounding his clandestine escape from his Russian national team in the summer of 2006. That’s because in leaving that squad behind — literally sneaking away from teammates at night during training camp so he could board a plane to a country that would grant him a travel visa to Canada — Malkin also had to suddenly abandon his family and friends.

His family was small, consisting of his parents and brother. His friends were few, a byproduct of growing up in a small town. Still, Malkin was 20 when he left everything he knew behind to chase an NHL dream. He did know, on some level, that being forced to break free of Russia’s grip on his career and life would forever change his relationship with his home country.

But he had no choice.

After the Penguins drafted Malkin in 2004, front-office personnel from Metallurg, Magnitogorsk’s prized hockey club, made a surprise visit to Malkin’s house. Under the guise of congratulations and celebrations, they pressured him into signing an extension to stay with his hometown squad. His departure, they said, would ruin Metallurg.

Malkin was 18. He was torn between beginning his dream of playing in the NHL and, as it was explained to him, being the downfall of a civic treasure.

Metallurg personnel refused to leave Malkin’s house until he signed an extension. That extension delayed his NHL debut by two full years.

It’s no coincidence that when Malkin finally was granted the chance to play for the Penguins, he scored in his first game. Then, he scored in his next five games.

“Never seen anything like it,” Sidney Crosby said of his then-new teammate’s historic burst onto the NHL scene. “I think that was the first real sign we all had how special Geno would be.”

Malkin went through so much to reach the NHL. His agent, J.P. Barry, hatched the plan for him to sneak away from the Russian national team during a training camp outside of Russia, a voyage that took Malkin to Toronto, Los Angeles and, finally, Pittsburgh. The whirlwind adventure dragged his emotions between excitement, fear and regret.

“My dream was to play in the NHL,” Malkin said. “This was not how I wished to get there.”

But even after a Calder Trophy and a sophomore season in which he finished second — to Ovechkin — in the Hart and Art Ross Trophy races, Malkin still had to lean on something he learned as a child to help him get to a point no Russian-born NHL player had gone before.

And that’s the second lesson of Malkin’s story: Pain comes before pleasure.

One day during a practice for his youth team in Magnitogorsk, Malkin fell hard onto the ice. His wrist was fractured. This happened a couple of days before a big travel tournament, which Malkin had eagerly anticipated because he felt his team could win. He had never won a championship to that point, and he wanted that first title.

His coach wanted Malkin to play, even in a limited capacity. So did Malkin’s dad, who believed his son could still help the team despite his right forearm being in a cast.

Malkin’s mother said no. And because she ruled the roost, that was that.

Except it wasn’t.

Young Evgeni Malkin, with the help of his father, persuaded his mother to let him travel with the team for moral support. She obliged, never knowing that Malkin had stashed his gear in one of the vans transporting players to the tournament. Without media coverage of any kind, there was no way for Malkin’s mother to monitor the weekend tournament. She simply believed her son had gone to cheer on his mates.

To her surprise, he returned home a few days later in tears — and with a mutilated cast. Malkin had played, cutting the cast at his wrist so he could better handle the stick. But his tears weren’t from physical agony, but rather because none of it — the sketchy plan by him and his dad, the betrayal of his mother’s wishes, the struggle to play with one healthy arm — had been worth it.

“We didn’t win,” Malkin said. “I played my best, but I was not in my best condition. But I could play (and) I should play great if I can play. I was not my best and we lost. I can’t forget even now.”

By his third NHL season, Malkin was in the conversation as one of the world’s best hockey players. Also in that group were the two men who would forever overshadow him: Ovechkin and Crosby. Even though Malkin won the Art Ross Trophy as the NHL’s leading scorer in the 2008-09 season, all eyes were on Ovechkin and Crosby for the first Penguins-Capitals showdown of the stars’ era in the second round of the Stanley Cup playoffs.

Malkin was seen as a supporting character, even though he scored an overtime goal in Game 5 in Washington that proved pivotal to winning the series. The Penguins won in Game 7, also in Washington, and returned to the Eastern Conference finals, which they’d won the previous season in a series where Malkin injured his ribs.

The pain of those injured ribs is not what haunted Malkin in the summer of 2008. It was how that injury limited him for the remainder of the 2008 Eastern finals and in the Stanley Cup Final, which the Penguins lost to the Red Wings. He used that memory — a nagging feeling that he somehow had let down not only his teammates and the city of Pittsburgh, but everybody who knew him — as motivation throughout the 2008-09 season.

Even his Penguins teammates didn’t know what was about to happen.

“I was ready,” Malkin said. “I had something to prove.”

Believe it or not, the Penguins were vulnerable to an upset by a Hurricanes team they would ultimately sweep in the 2009 Eastern finals. Pittsburgh had come off a couple of emotional series wins against the Flyers and Capitals — the franchise’s two fiercest rivals — and was looking ahead to a rematch with the Red Wings in the Cup Final.

“I thought we could get them,” said Jim Rutherford, who was the Hurricanes’ general manager at the time. “(The Penguins) might have been a more talented team than us, but I thought we could get at least one of those early games in Pittsburgh, and then make it a long series.

“I still think I was right. Malkin just wouldn’t allow it.”

In the first game, at Pittsburgh’s old Civic Arena, Malkin scored and set up a goal in the Penguins’ 3-2 victory. It was Game 2, though, that will forever be remembered as what Crosby called “The Geno Game.”

Or, as former Penguins winger Bill Guerin said: “You never think a series is over after Game 2, but it was over after Game 2. Nobody was stopping Malkin, and everybody knew it.”

The signature goal of the historic season is the stuff of legend in Pittsburgh.

Malkin blew open a tight game as part of a three-goal, one-assist performance that announced to the hockey world that he would be the one administering the pain this time.

The faceoff was in the left circle, the prime spot for Malkin to win a draw. When the puck went forward, it looked in real time as though Malkin had been beaten cleanly. He hadn’t.

“(Malkin) pushed it forward, got it behind the goal, swooped around and then he turns around and lifts a backhand,” said Max Talbot, Malkin’s right winger throughout that postseason. “The guys on both teams were stunned — all except Geno.”

“I had no clue he was going to try it,” said Talbot, who had the best view of anyone on the goal that is now affectionately known as “The Geno.”

“I remember thinking, ‘We lost the faceoff,’” said Ruslan Fedotenko, the left winger on Malkin’s line during the Penguins’ 2009 Cup run. “It was only after he scored that I realized what Geno had done.”

For coach Dan Bylsma, time seemed to stand still. He needed to watch a replay to realize what had just happened.

“The degree of difficulty of that entire play is off the charts,” Bylsma said. “To try it — forget doing it, but to try it — in an Eastern Conference final takes confidence that I would have never had, and I don’t think you’ll find many players that would even think about it.”

Added Crosby: “No, I don’t think I would. But that’s Geno. Man, he was awesome in that series; that whole playoffs, really.”

Malkin described the goal as “not too great.” Really.

“Everybody sees spin-o-rama and I score, but my job was to push the puck to Max and then I go to the net,” he said. “The puck went too deep and I have to get it — then, you know, it’s, like, ‘I do it myself.’

“After I spin around, the puck was on my stick good and it was time to shoot. That’s it! So people tell me about that goal, but I don’t know — I think I scored better ones. It’s not my best, but everybody loves it.”

“Not my best,” he says, but the goal in Game 2, which the Penguins won, is what Malkin considers “my most important.” The performance in that series — six goals, three assists in a four-game sweep — “was maybe my best hockey,” he said.

“But I play good against Detroit, too,” Malkin said. “I had to. I owed the team because we lost the year before.

“When you don’t win, it’s hell. When you get close and lose, everything you feel is empty, everything hurts. But pain, you know, can be good. It teaches you.”

With two goals and six assists in a seven-game classic against the Red Wings, Malkin helped steer the Penguins to the Stanley Cup. He was voted the Conn Smythe winner, becoming the first Russian-born player to win that award.

And he finally won a championship.

“I’m lucky, maybe, my first championship is the Stanley Cup,” he said. “You always love your first.”

Two more Stanley Cup titles later, as well as the Hart Trophy for the 2011-12 season, and Malkin is among only a handful of players to have won the Calder (for rookie of the year), Hart (for MVP), Ross (for the single-season points title), Smythe (for playoffs MVP), Ted Lindsay (for player-voted MVP) and the Stanley Cup.

None of those awards, nor his multiple Cup wins, was enough to earn Malkin a spot on the NHL’s 2017 list of the 100 best players of all time. The slight crushed him, bringing back feelings from his youth that he would never be seen as a great hockey player because the greatest Russian hockey players came from Moscow or Saint Petersburg, not places like Magnitogorsk. He also couldn’t help thinking back to all the talk early in his career about how the NHL belonged to Ovechkin and Crosby, even if Malkin was right there with them in terms of production and achievement.

“It hurt me deeply,” Malkin said. “What must I do to be seen as one of the best players? I think I am.”

Sergei Gonchar is one of Malkin’s closest friends. He’s also Malkin’s former teammate with the Penguins and with the Russian national team. He’s admittedly biased, but…

“I have Geno in the top three of Russian players,” Gonchar said. “There’s Alex, and I think Geno is a better overall player, and there’s Sergei Fedorov, and Geno might be better than him by the time he’s done.”

Gonchar might be a little biased, but he might actually be underselling Malkin’s legacy. It’s certainly debatable and it’s clearly close, but of the nine Russian players who made The Athletic’s NHL99 list, Malkin lands second — behind Ovechkin and a shade ahead of Fedorov at 33. For good reason.

Over his career, Malkin has been worth around 46 wins, which is second among Russian-born players behind only Ovechkin at 60.6. Part of that difference is a matter of Ovechkin suiting up for 300 more games than Malkin. On a per-82-game basis, Malkin has averaged 3.85 wins per season while Ovechkin is only narrowly ahead at 3.90. Nikita Kucherov (3.91) and Pavel Bure (3.87) also rank that highly, but neither has the longevity of Ovechkin and Malkin.

“Alex and Evgeni will always be talked about together — in Russia and the NHL,” Gonchar said. “It’s good company.”

Malkin lived with Gonchar during his earliest NHL years, but Gonchar first noticed Malkin’s desire to stand out among Russian players when they spent the 2004-05 NHL lockout playing for Metallurg. Then, Gonchar said, Malkin was “this big, talented kid who talked about being seen as great among Russian players but also becoming one of the best players in the world.”

“He did it,” Gonchar said.

Malkin needed his first NHL season to acclimate himself to the North American lifestyle as much as its brand of hockey. Even then, as he was rolling toward consensus top rookie honors and proving Patrick’s prediction correct — that the Penguins had found a franchise pillar in Malkin — the comparisons to teammate Crosby and rival Ovechkin weighed on Malkin.

“Evgeni doesn’t seek the spotlight, but he deserves more of it than he’s been given,” Gonchar said. “He never said it bothered him, but if you know him you could tell it did because he wanted to be the best.”

Malkin had one more lesson to learn early in his career, and it’s one he has had to carry with him throughout: Only worry about what you can control.

“I’ve learned many lessons in life,�� Malkin said. “Some help me with hockey. Others help me with life, you know?

“I would like people to know my story and see you can overcome disappointment, pain, and be a champion.”

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was asked to make a Chris Kreider/Mika Zibanejad primer

Naturally I jumped at the opportunity. Let’s dive right in, shall we?

Chris Kreider

This motherfucker

Graduated college because his mother asked him to do that before going pro

Loves his mother

Has a communications degree, sharp as a tack even if he does sometimes have regrettable facial hair

“Sharp as a tack” except for that one time he ignored his body trying to tell him something was wrong and nearly died

Plays piano, guitar, and saxophone

Has a beautiful baritone singing voice

Has been known to serenade his teammates during practices

Avid reader, takes his Kindle everywhere

Tends to run over goalies (bad Chris, NO)

Teaches his teammates new words for fun

Speaks at least three languages—English, Russian, and Spanish. He’s rusty in Russian but he speaks it to the baby Russians on the team to make them more comfortable. Him speaking Russian

He really loves dogs. Like really loves dogs. I mean really.

I could go on, honestly

Mika Zibanejad

This motherfucker

French-braids his hair for special occasions (see above gif)

Born in Sweden, but is actually half-Finnish, half Iranian. He speaks Swedish, Finnish, Farsi, and English.

Drafted sixth overall by the Senators in 2011, traded to New York in 2016. Had literally just bought and started building a house just before he was traded.

Is left handed, wanted to learn guitar at school but they didn’t have any left handed ones so he took drums, wasn’t impressed.

DJs in his spare time. Is actually really good at it?? Has played for multiple Rangers’ charity events, as well as friends’ weddings. Did the player intro song for the team’s 2018-2019 season. Makes some incredibly catchy music. My favorite

Owns a restaurant in Stockholm with his brother and several friends—announced last year a portion of proceeds are going to women’s hockey

Volunteers with kids in Sweden to help grow the sport and encourage interest

Oh yeah he’s also really good at hockey?

Nbd he just scored five goals in a single game one time and here’s a video of all five

His father had come to visit and told him as they were leaving Mika’s place for the arena, “you know, I’ve never seen you score a hat trick”. So Mika casually went out and got five goals instead because that’s just the kind of overachieving bastard he is

Wraps his stick for Pride Night (so does Chris), and actually scored those goals on Pride Night, so he said GAY RIGHTS and I think that’s very sexy of him

Adores his niece Nikki and brand new nephew Knox, him and Nikki

His hair should be illegal

Takes the rookies under his wing, mentors them, and often lets them live with him until they find places of their own.

Will almost certainly wear the C sooner rather than later

And now for my favorite part

Chris and Mika’s relationship

Chris was Mika’s first liney when he arrived in New York

They bonded immediately

Chris has visited Mika in Sweden over the summers not once but at least twice that we know of

The first visit - this picture tragically cut off the caption Mika put on it, which was “reunited with bae 😍”

They did an interview game on how well they know each other. When they were asked who Mika would take on vacation with him, they both instantly answered “20” and Chris muttered, “You’d better take me.”

(Also, Chris made a fantastically dorky reference to Robots [a movie like three people saw] at the beginning of that video, so that made me love him even more)

Here’s the video, watch it at your peril

The second time Chris visited him in Sweden

Chris represented America at Worlds last year. Mika didn’t represent Sweden, but he went to see Chris play. (Don’t have a source on this)

They’re addicted to hugging each other

No really

Like actually addicted

You think I’m joking?

Mika’s flirting is… not subtle

Oh did you think we were done with hugging clips?

That’s cute

Chris literally held Mika’s hand on the bench

MORE HUGGING, MOTHERFUCKERS

Mika has a Chris-specific smile, I’m not joking

Chris: *says anything* Mika: *gazes at him adoringly*

Mika is not shy about being tactile, and Chris clearly loves it

This one just makes me laugh because Chris is being so intense and Mika’s having none of it

In conclusion, please join me in appreciating not only the bond these two idiots share but also their individual personalities, because they’re both pretty damn great

420 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nico Hischier/Jonas Siegenthaler Primer

(Gif source)

Nico Hischier

First overall pick in the 2017 NHL Draft (love you, NolPats).

"Mentored" by Taylor Hall--I'll let you decide the definition of mentored there, pals.

Current New Jersey Devils captain at 23, and THEY ALL LOVE HIM.

The future of Swiss men's hockey pretty much lays on his pretty shoulders, right along with New Jersey's cup dreams.

Nico's had a rough go with injuries. The day Jonas got traded to the Devs was his first game back after missing pretty much the entire year.

Yes, he really does go about his daily life looking like this.

Source: Nico's Insta

Jonas Siegenthaler

Drafted 57th overall in the famed 2015 NHL Draft by the Caps.

He played for the ZSC Lions in the Swiss league with Auston Matthews (can you believe AMatts was this blessed?).

Unfortunately, the Caps have a pretty deep D-core, so Jonas bounced around a bit between the AHL and the NHL.

The Swiss Embassy really loved him though, which like, FAIR.

Unlike most of the hockeys, Jonas is extremely competent in the kitchen! The Caps did a Caps Social Cookoff between him and Jakub Vrana and it's a must-watch.

The cooking thing is EXTREMELY important to the narrative, as you'll read later on.

Yes, he also goes about his life looking like this. Hot AND he won't make you eat Kraft Dinner on your date.

THEM 🥰

Their public history started when Jonas played with Nico's older brother, Luca, on the Swiss U18 team in 2012. Two years later, Nico and Jonas played together on the 2014 U18 team.

Jonas posted the CUTEST picture of them when they were babies playing on the same U20 team. Imagine crushing on your brother's older friend, and now you're his captain. ANYWAY.

In 2017, they went on a boys' trip together just shortly after Nico got drafted.

Source: Nico's Twitter

April 11, 2021, after being scratched for 15 games, the Caps traded Jonas to the Devs. Nico's team. Nico, of course, insisted Jonas stay at his place in New Jersey.

Please note the way Nico's face transforms when someone asks him about Jonas (starts at 2:10).

youtube

For even more pain, Amanda Stein, the Devs reporter, tweeted this about the video above:

When Mark Recchi also ships it, you know it's true love (starts at 5:45).

youtube

Tumblr user jakejuentzel (they're the best, for real) made the best gif set from the video above that includes this gem:

Jonas didn't a chance to play much after the trade because he got Covid, but he was able to play the last few games with the team. It was a rough season, but it's okay, because Nico helped him.

Jonas and Nico also spoke about each other in their exit interviews.

Jonas: "I was pretty excited to get here...I knew Nico already from the national team. We're not from the same hometown, but like we knew each other...we have the same interests and all that stuff, so it works out pretty good. I've never played with another Swiss guy on a team here, but it's kind of special. There's not a lot of Swiss guys and if there's two Swiss guys in one team, it's even more special. He helped me a lot, which made it a lot easier. I'm really happy about it."

Nico: "It was great. I obviously knew Jonas before he got traded here, so when he got traded here, I was super excited. I was excited to...like, I knew him well, so I was super excited to have him come here and show him around and I knew what he could bring to the team. So I was both ways excited on and off the ice."

And then Nico just had to go in for the KO:

"He usually spends his summer in Zurich and I spend my summer in Bern. But we usually see each other a couple times during the summer but not for workouts."

Nico. Nico. Buddy. Pal. I just wanna talk. What do you even mean by "but not for workouts".

The most devastating part, though, is this bit at the end:

You must see the gif set by jakejuentzel, it's required reading.

Nico, smug as hell, because Jonas cooking for him and taking care of him next season is just a foregone conclusion.

Speaking of the next season, this season, the Devs are uh, doing their best. Nico and Siegs are still in love, and while it has not been confirmed, circumstantial evidence says they still live together.

For one, they BAKED BREAD TOGETHER at the start of the season, and the best Tumblr users presented a very credible investigative report about it.

They're also seen frequently walking in together to games. Obvious proof of cohabitation.

The King and His Lionheart

Nico has been the face of Swiss men's hockey and the New Jersey Devils for the last several years. It's a lot to carry on his shoulders, even if his teammates all love him. The Devs is a young team, and I imagine it's difficult for Nico to allow his teammates to see a glimpse of his struggles and what he's feeling.

When I think of Jonas, I immediately think of words reliable and steadfast. He's not the flashiest guy in the world, but he's someone who can be depended on, in any situation.

Out of everyone in the Devs, Jonas is the one who's known Nico the longest--and arguably, the one who also knows him the best. It's easy to see Nico leaning on Jonas in the privacy of their own home, because as Nico's said repeatedly before, Nico knows Jonas well, and the reverse is likely true.

Nico is willing to sacrifice everything for his team, including his own health and well-being sometimes if it means success for his friends and his teammates.

Jonas probably also cares about team success, but he's had a markedly different experience with teams than Nico. He's bounced around between the AHL and the NHL, and with the trade, I think even more so, his loyalty isn't to a team. I'm not saying his transformation from riding the bench to one of the best defensive defensemen in the league this season is entirely due to Nico, because he's skilled and he's good. But also, the Devs have been struggling all season long, and it's not unwarranted to think Jonas' play on the ice is one of the ways he can lift some of the burdens from Nico's shoulders.

Because remember when I said Nico is willing to sacrifice everything for his team? Nico puts the team above self, but Jonas? Jonas puts Nico above everything.

TLDR: In Conclusion Thanks to my co-president, msmargaretmurry, for her help with this part.

So you have Nico, the boy king of Swiss men's hockey/New Jersey, who is universally adored but has struggled to lead his team to success, for a lot of reasons that aren't his fault, but also because of some really terrible luck with health and injuries.

And then you have Jonas, who is very big struggled for years to find his footing in the NHL, and now that he has, he gives a lot of credit to Nico, who once upon a time was Jonas's teammate's little brother, and then was Jonas's teammate and friend, and now is Jonas's captain. They've very loyal to each other, and carry a lot of feelings about their shared homeland together. Also, oh my god they were/are(??) roommates.

There’s just so much potential here. You’ve got friends-to-lovers. You’ve got childhood friends-to-lovers. You’ve got teenage-crush-on-my-big-brother’s-hot-friend-and-now-he’s- living-with-me-oh-god.

This is ripe territory for fwb-turned-feelings, or having a summer fling because you don’t think you’ll have to see each other much during the season and then whoops, you’re on the same team. You’ve got the most nauseatingly sweet domesticity you could ever ask for, AND you’ve got two guys both under very different types of massive pressure from the sport they love who find support in each other.

If nothing else, Nico is literally obsessed with Jonas' size and mentions how big he is in every interview where he's given the opportunity to talk about Siegs.

And they baked bread together. Come ON.

BUT WAIT

If you're STILL not convinced, here's what they had to say about each other earlier this year:

Nico on Jonas

I played with him growing up, also (in the) national team, so I knew exactly what he can bring to a team. And he's doing exactly that on this team. He does a lot of dirty work that let's say maybe not on the score sheet, but it's really important for a team to have success. I feel he's playing unbelievable for us.

Jonas on Nico

You know, that's probably why he's captain. Every night, he does those little details. Maybe people don't see very often but we on the bench see it. That's just what makes him so good. That's a true leader for me. You just gotta watch him on the ice. He's such a hard worker, blocks shots. For me, that's a true leader.

THEY'RE IN LOVE, YOUR HONOUR.

For more feels and visuals, please consult jakejuentzel's frünn tag. If for some reason, you want to watch me scream about them, my tag for them is the king and his lionheart.

I love yelling about them, so please don't be afraid to send me an ask or message!

165 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I had to do it, I’m not even sorry. You can find all links, videos, and pictures on here. Enjoy!

PS: You can find my flames primer (of sorts) here.

631 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nathan MacKinnon is just a bigger version of ultra-driven ‘Nate the Kid’

Nov 10, 2022 (x)

HALIFAX, Nova Scotia — Inside Cole Harbour Place, where a mural of a pond hockey game looks over the main sheet of ice, a young boy jumped out. He might have been smaller than most of the kids, but that didn’t stop him from seizing the puck whenever he wanted. His head was always up as he stickhandled, even as a 9-year-old. He had power on skates unlike the others. It was as if he galloped.

As the youngster dominated his opponents, coaches Charlie MacLean and Dave Peters sat nearby, preparing game plans for their team, which was scheduled to play later in the day. At one point, MacLean walked over to the ice. Before long, he had called for Peters to follow. He had to see this player.

“You peek your head in,” Peters says now, “and all of a sudden you see the future best player in the world.”

That was the first time he laid eyes on Nathan MacKinnon.

Cole Harbour Place is full of pictures and memorabilia from Sidney Crosby, the Penguins captain who grew up playing at the rink and became the world’s most famous hockey player. Just down the wall is one dedicated to MacKinnon, the kid who followed in his footsteps.

MacKinnon’s case is a time capsule of sorts. There’s a picture of a chubby-cheeked 2-year-old, grinning as he stands in skates for the first time. He’s smiling in another picture nearby, one in which he’s slightly older, eating a snack while wearing a black Tim Hortons jersey. There are hockey cards from his youth team, the Cole Harbour Wings, as well as trophies and old jerseys. The shelves are full of memories, tokens showing a player’s journey from childhood to stardom.

“He was like he is now,” says Jon Greenwood, another one of MacKinnon’s former coaches. “Just a smaller version.”

MacKinnon’s progression made him a Stanley Cup champion and a three-time Hart Trophy finalist and landed him at No. 74 on our list of the greatest players of the NHL’s modern era. MacKinnon, now in his 10th season with the Avalanche, brought the Cup home to the Halifax area this past summer. His mom, Kathy, worked in the government building and his dad, Graham, was a track supervisor for the Canadian National Railway. The city’s people are proud that MacKinnon grew up there, proud that he’s still one of them. MacKinnon shares that pride.

Graham MacKinnon played a bit of goalie growing up in Springhill, Nova Scotia, and he taught his son to skate at a young age. Plenty of other kids in the area played, but MacKinnon never felt the sport was forced on him. It didn’t need to be. Hockey became more than just a hobby or something fun to do. It consumed him.

“I just remember never not wanting to go to the rink,” he says. “I always loved to play.”

His childhood home, where his room is still decorated with the hockey posters he hung as a kid, is next to what he calls a glorified pond. The small lake freezes quickly in the winter, and he spent hours shooting pucks at a battered net, sometimes with friends and sometimes alone. He’d make the 10-minute walk home from school during lunch, throw on his gear and get a skate in, stopping only to eat mac and cheese on the snow bank.

Cole Murphy, one of MacKinnon’s closest friends growing up, remembers the first time he saw MacKinnon skate. They were both around 6 years old and playing against each other when MacKinnon darted down the ice. At that age, none of the kids got air under the puck when they shot. But MacKinnon was different. Murphy watched him shoot the puck into the glass.

That memory is still fresh two decades later. Many of the people around Halifax, be it Murphy or Peters or MacLean, don’t forget the first time they saw MacKinnon on skates.

“Obviously, he’s one of the hardest-working people I know,” Murphy says. “But you don’t get to where he was without some physical gifts as well.”

Greenwood first worked with MacKinnon at the rink when the young center was 11, and the coach quickly noticed how hard he was on himself. He’d be furious if he missed the net during practice, and he’d challenge his coach to shooting competitions after the team was done skating.

That sometimes put Greenwood in a tough situation. If the coach won, MacKinnon would grow angry at himself. But if MacKinnon outshot him, he would question if Greenwood was putting in his maximum effort.

“I knew when he wasn’t trying,” MacKinnon says.

Greenwood quickly realized he had no choice. He couldn’t take it easy. “I might have beat him once or twice when he was that age,” he said. “But I’m sure that stopped shortly after.”

MacKinnon didn’t simply want to be the best. He wanted to dominate. MacLean, who coached him at the bantam level, saw that most not on the ice, but when the team did wall sit exercises. MacKinnon was able to hold his longer than everyone else, but even when the second-to-last person stopped, the star center would keep going.

“He’d go 10, 15 minutes past everyone else,” MacLean says. “It wasn’t good enough to be first. He had to dominate them.”

He also worked at areas of weakness on the ice. He approached Peters about getting better in the dirty areas. The coach talked to him about where to stand, one day putting him directly in front of the net, where he’d be in position to screen the goalie and deflect pucks. MacKinnon was scared of the puck at the time, so this wasn’t a comfortable place. But he did as the coach said, and Peters began firing slap shots at him so he could practice.

“If he missed I would’ve been dead as a 12-year-old,” MacKinnon jokes now.

Though hockey was his passion, it wasn’t his only sport, which Murphy believes helped keep both of them from getting burned out. On summer weekdays, their parents dropped them off at Abenaki Aquatic Club, and they’d kayak in preparation for a few regattas every year. MacKinnon believes the paddling helped give him a strong back, and the coaches, timers in hand, would make the kids run a 5K every morning.

MacKinnon, Murphy and their friends swam and played basketball in their free time at Abenaki. And, in a major development in 8-year-old MacKinnon’s life, the summer days at the club gave him the chance to flirt with girls for the first time.

“Didn’t go great, but I tried,” he says, laughing.

He was much better at hockey. His fire and competitiveness, in Greenwood’s eyes, were the separator. It’s part of the reason Murphy isn’t surprised watching him dominate in the NHL. Don’t get him wrong: He’s proud of his friend. But this always felt like the path he’d go down.

“I’ve had a few coachable, competitive kids before, but never with that skill,” Peters says. “I’ve definitely seen skilled kids before, but never with that mindset.”

MacKinnon was the rare marriage of both. He was, in Peters’ eyes, a perfect storm.

Some players are worth gigantic risks. The Halifax Mooseheads were coming off three dismal seasons — three consecutive years with a point percentage under .335 — and general manager Cam Russell wanted to make sure that string of disappointments stopped.

“We needed a boost for our organization,” Russell says.

He had a solution in MacKinnon, who had spent his first two years of high school at Shattuck-St. Mary’s, a private boarding school and hockey powerhouse in Minnesota. But there was an obstacle. MacKinnon was the most talented player in the QMJHL draft, and the Baie-Comeau Drakkar had the first pick.

The MacKinnon family told Baie-Comeau that Nathan had no plans of reporting there if the club drafted him, and Russell tried to trade for the pick. Still, the Drakkar selected MacKinnon, but when it became clear the player’s stance wasn’t going to waver, the club started looking to trade his rights.

Enter the Mooseheads. MacKinnon grew up cheering for the team, and his family had even billeted a former Mooseheads player when Nathan was a kid. He didn’t come cheap, though. To acquire him, Russell traded Carl Gelinas — the team’s leading scorer from the year before — another depth player and three first-round picks to Baie-Comeau.

“We knew that with what we were giving up, if Nathan wasn’t a player, was going to deplete the franchise significantly moving forward,” said Mooseheads president Brian Urquhart, who was the vice president at the time.

One fan sent Russell an email, ripping him apart for trading such a haul for an unproven teenager.

“I am struggling to understand this decision and fear that your fans might have to watch a team that will not do well for years to come,” it read.

But a player with club-altering potential, the general manager determined, was worth the hefty price. So after playing two years in Minnesota, MacKinnon headed home.

Greenwood always wondered when MacKinnon would reach a level he couldn’t dominate. Major junior, he thought, might be where his star player hit a speedbump. As a 16-year-old entering the QMJHL, he’d be playing against future NHL players, some of whom were multiple years older than him. Growing pains would have been understandable.

“It didn’t happen,” says Greenwood, who would soon learn to never be surprised by what MacKinnon does on the ice.

A few days before his training camp, MacKinnon walked into Mooseheads coach Dominique Ducharme’s office for a meeting. MacKinnon wanted to be in the NHL as soon as possible. Ducharme, who had seen his dynamic play and skillset, wanted to help him get there.

“We have two years,” Ducharme said. “730 days. Take those days one-by-one and make the most of it and you’ll be ready for that.”

MacKinnon bought in, and he jumped out from the moment he first took the ice. Goaltender Zach Fucale remembers his presence the first day of practice. His shots on net had a zip to them. The goalie remembers knowing pretty quickly that his new teammate would be one of the best players in the league.

“We were both only 16 and I felt like I was years behind,” Fucale said.

Teammates knew MacKinnon was bound for the NHL. “Don’t forget us,” they’d joke with him, Fucale remembers. These expectations were nothing new for MacKinnon. ESPN ran a story when he was 14, calling him “Nate the Kid,” a reference to Crosby’s “Sid the Kid” nickname.

“I never really sensed (he felt) a lot of pressure,” Greenwood says. “If he did, he certainly always seemed to rise to it.”

During MacKinnon’s first year with the Mooseheads, he found out he hadn’t been invited to Canada’s World Junior Championship training camp. He was in gym class when the list was released, and he stared at it, angry tears coming to his eyes. That disappointment, paired with the Mooseheads’ next game, became part of MacKinnon’s lore in Halifax.

Playing against the Patrick Roy-coached Quebec Remparts, MacKinnon put together a five-goal game. Every goal was different: He redirected a pass, backhanded a puck in on a breakaway, deked out a goalie from the side, finished a wrap-around and flipped in an empty-netter. As celebrating teammates approached him after his second goal — the breakaway — he lifted his arms. He stared at them wide-eyed, his mouth hanging open, as if shocked at his own abilities.

MacKinnon wasn’t actively thinking about what he viewed as a world juniors snub, but subconsciously, he believes, some extra juice was inside him.

“It felt like a statement game,” Urquhart says. “It was just dominant.”

Halifax returned to the playoffs that year, reaching the third round, and in MacKinnon’s second and final season with the Mooseheads, they won the QMJHL championship and the Memorial Cup. In the final, MacKinnon scored a hat trick to upend fellow draft prospect Seth Jones and the Portland Winterhawks.

“Nate was one of the reasons we kept that standard so high, because that’s how he operates,” Fucale says. “He keeps the bar high and will not accept anything under that.”

The Stanley Cup sat downstairs on a table at Saltyard Social, a two-story restaurant right next to the Halifax waterfront. The weather was perfect for MacKinnon’s party with the Stanley Cup, and he mingled with guests as he ate donair wraps and sipped drinks. The 2021-22 section of the trophy had yet to be engraved, but soon his name, along with the names of his Avalanche teammates, would be on the silver metal.

Loved ones were everywhere. Crosby, his idol-turned-friend, was there, as were his old coaches. His parents and sister, Sarah, laughed with the guests.

“He’s the happiest guy in the world,” close friend Ian Saab said earlier in the day.

MacKinnon poured all his energy into making it to the highest level. That was his focus. When he spoke in front of a crowd in downtown Halifax earlier in his Cup day, he said he wished he enjoyed the journey a bit more. Back in Denver, he repeats the same sentiment.

“All I wanted to do was make the NHL,” he says.

But perhaps all the reasons he couldn’t fully enjoy the ride — his singular focus, the rigorous drills and workouts he put himself through, the forward-looking mindset — are why he is what he’s become. If he didn’t have that ambition, that hunger growing up that was never quite satisfied, could he have become this version of Nathan MacKinnon? Perhaps he could have found a healthier balance, and taken things a little less seriously. But as coaches have said — from Greenwood coaching him as a child to Jared Bednar coaching him now — if you have a player with MacKinnon’s fire, you don’t try to contain it.

Crosby will always be the first generational player to come from the Halifax area. Because of him, kids in the city — including MacKinnon — grew up cheering on the Penguins star. Over time, Pittsburgh shirts didn’t jump out much to Greenwood. It all made sense.

The Penguins apparel isn’t going anywhere. Greenwood still sees it plenty. But he’s noticed recently more and more Avalanche gear popping up. It turns out, in this city along the harbor, there’s room for two.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The stories you don't know about Evgeni Malkin's journey to 1,000 points

Mar 13, 2019 (x)

Evgeni Malkin is not one to take for granted having scored 1,000 points in the NHL. However, but he does have more lofty goals on his mind.

“I know what (Sergei) Fedorov did,” Malkin said, referring to his childhood idol. “I want to have more than him.” Goals? Points? Games? “More goals. More points. Of course. And Fedorov has three Cups, same as me. So I need one more. Maybe two. I don’t know. At least one.”

Despite his omission from the NHL 100 a couple of years ago, Malkin remains a star with few peers regarding achievements. He is one of only a handful of players to claim the Stanley Cup, and the Art Ross, Calder, Conn Smythe and Hart trophies. He is also one of only five Russians to join the Millennium Club among scorers.

Those who know Malkin best shared their memorable stories from his run to 1,000 points.

Geno pulls rank Sidney Crosby thought he knew “the rules.” He was wrong. And even though Malkin spoke few words of English during his earliest days with the Penguins, he knew enough to pull rank on the other young superstar center in Pittsburgh.

Prior to Malkin’s first regular-season game at the old Civic Arena in 2006, he and Crosby instinctively remained behind as Penguins teammates took to the ice for the opening period. As it came down to Malkin and Crosby, each player looked at each other wondering which one should go next.

“And we couldn’t really say it, right?” Crosby said, smiling. “And I’m, like, ‘Geno, you can go.’ I mean, like, ‘You. Can. Go.’ And he’s, like, ‘Oh no, you go.’ You know? And that’s, like, the most he would hear at that point.”

Again, Crosby insisted that Malkin be the penultimate Penguin to take the ice. Malkin held firm.

Crosby suggested they play Rock, Paper, Scissors to break the stalemate.

“And then I’m, like, ‘Wait a second, he’s not going to know what Rock, Paper, Scissors are,’” Crosby said.

Crosby next tried cutting to the chase. He explained that Malkin should go next so that Crosby could go last. Again, Malkin held firm.

“He goes, ‘No, three years (in) Super League,’” Crosby said. “I go, ‘This is the NHL, I went last year.’ He goes, ‘Super League (is) best league in the world.’ And I’m, like, ‘What?!’

“What he just said was more than I heard him say up to that point.”

And at that point, Crosby experienced Malkin’s preference to make a point in a roundabout way.

“He was basically trying to say, ‘Hey, I’m older, you’re younger — I’m going (last).’ But he couldn’t say that in English. So I said, ‘OK.’ And so I ended up going second, and that’s how it goes.

“That’s the story of why Geno goes last, you know? To this day, we still go in that order.”

Geno gets a crush

Max Talbot had no idea how he would handle rooming with Malkin on the road during the 2007-08 season. Between them, they spoke three languages but didn’t have one in common.

After the first couple of road trips, Talbot realized that he and Malkin did have something in common: the “Transformers” movies. During his second NHL season, Malkin became obsessed with the original “Transformers” film after Talbot purchased it on their hotel room’s television the night before a game.

“Oh, Geno watched it, like, every night,” Talbot said. “I mean, it’s not a great movie, you know? You can see it once or twice. But Geno … he always wanted to watch that ‘Transformers’ movie. You could say it got a little bit annoying.”

One night, Talbot attempted to coax Malkin into going out for dinner. Malkin declined. He invited Talbot to order room service and join him for a viewing of his favorite movie. It became the last straw.

“I said, ‘Geno, why do you always watch that movie?’” Talbot said. “He said, ‘Look (at) girl, learn English.’ And, honest to God, I probably laughed for the next five minutes.

“He had a crush on that actress (Megan Fox). He watched the movie because she was in it, right? And I guess (Sergei) Gonchar had told Geno to learn English by watching the same movie over and over. So, Geno watched that ‘Transformers’ movie because he liked that girl.”

A few weeks later, during his first group interview with Pittsburgh media, the ice was broken when Malkin recognized the word “Transformers” during a question I asked. The next day, when reading my story to Malkin, Gonchar did Talbot a favor.

“Gonchar said to Geno, ‘You know, there is a second movie,’” Talbot said. “And all I could think was ‘Why didn’t I think of that?’ At least it wasn’t the same movie the rest of the year.’”

Geno learns to lie Technically, these next anecdotes are not from Malkin’s days with the Penguins. However, they were provided by his parents Vladimir and Natalia, who almost as beloved in Pittsburgh as their son.

As a 4-year-old in his native Magnitogorsk, Malkin and his father played 1-on-1 hockey outside the apartment complex where the family lived. Evgeni was behind the net one day when Vladimir shot a puck that deflected and hit Evgeni in the eye.

“I said to him, ‘What do we do? Your mom will surely be upset,’” Vladimir said. “He said, ‘Let’s not tell mom, she won’t let us play anymore.’”

Later that night, during supper, Natalia never asked her youngest son or his father about a mark near Evgeni’s eye. She did not say a word about anything during dinner.

“You could tell she knew,” Vladimir said. “We never have talked about it.”

About seven years after that incident, Evgeni was again injured — this time during an off-ice training session. He landed wrong while jumping. His leg was broken, and Evgeni was forced into a cast and to use crutches.

“This was before a tournament,” Natalia said. “We let him go with his teammates, but insisted, of course, that he could not play.”

Natalia and Vladimir were unaware that Evgeni’s coach had seen him playing tennis — the sport was a favorite pastime for Evgeni and elder brother, Denis — while on the crutches. The coach was convinced Evgeni could still help their team win the tournament even though Evgeni could not walk.

At the rink, Evgeni’s teammates helped him cut the cast off his leg with a rusty saw and then cram his foot into a skate boot. Evgeni returned home without a cast, still using crutches and also carrying a trophy awarded to the tournament MVP.

“I was not happy with him; but, yes, I was happy for him,” Natalia said. “It was never easy to keep him from hockey. I blame his father.”

Geno sees his future

Penguins centers Evgeni Malkin (left) and Sidney Crosby raised the Stanley Cup for the third time in June of 2017. (Christopher Hanewinckel / USA Today)

The day before Game 7 of the 2009 Stanley Cup final — so, the day before the biggest game of his life — Malkin walked into the players’ lounge at Civic Arena and spotted me sitting against a doorway’s wall. During a 20-minute conversation, he discussed the many differences from the previous postseason, which ended with the Penguins watching the Detroit Red Wings skate with the Cup in Pittsburgh.

Malkin, who played injured during that 2008 Cup final, was healthy this time around. He had the postseason lead in scoring to prove it. But he wanted more than the Conn Smythe Trophy he would ultimately claim.

He pointed to a picture on the wall that showed Mario Lemieux and Jaromir Jagr each holding up the Stanley Cup from the Penguins’ championship win in 1992.

“Me and Sid,” Malkin said. “We get our picture. It’s time.”

On the page of my notebook, I scribbled Malkin’s words and marked the time he said them into my digital recorder. I asked if I could write that part in my story advancing Game 7 at Detroit.

“Yes, you write (it), Rossi,” Malkin said. “Because we (will) win.”

The Penguins won the 2009 final. The Red Wings watched them take laps with the Cup on Joe Louis Arena’s ice. It was Malkin’s first team title at any level as a professional.

He needed another couple of Cup wins by the Penguins to finally get that picture with Crosby, though.

It was taken after the Penguins finished off the Predators at Nashville in Game 6 of the 2017 final. As he had in 2009, Malkin was the top scorer in the 2017 postseason. On the ice, he and Crosby recreated the Lemieux-Jagr pose from 1992.

That picture hangs in Malkin’s condominium on Fisher Island in Florida.

Geno gives props Gonchar had been gone from Pittsburgh for a couple of seasons when Malkin headed to Las Vegas for the NHL awards show in June 2012. Though their bond had strengthened in Gonchar’s absence, Malkin’s big night was not on Gonchar’s mind the evening of the broadcast.

“We were just sitting down at the table for dinner, and I turned on the TV with (eldest daughter) Natalie to watch cartoons,” Gonchar said. “I start getting all these text messages: ‘Great job.’ ‘Such wonderful things for Evgeni to say.’ And I didn’t get it — like, ‘What are they talking about?’”

Gonchar and his family had not planned to watch the televised broadcast of the NHL awards show. “I knew he would win,” Gonchar said. “I knew he would tell me about it.”

Malkin had already given one acceptance speech at the ceremony, so he was somewhat unprepared when taking the stage to accept the Hart Trophy. And in a callback to his first couple of seasons with the Penguins, when Malkin lived with the Gonchar family, he turned his MVP moment into a tribute to his best friend.

Thankfully, that best friend’s daughter showed Gonchar a video replay of the speech — after the cartoons, though.

“You know, I wanted to talk to him right away — after those text messages,” Gonchar said. “I called and left him a message. He never called me back.”

Instead, Malkin showed up the next afternoon at Gonchar’s house. He had a miniature Hart Trophy with him. And a fishing rod.

“He spent, like, the next 10 days with us,” Gonchar said. “It was a lot of time fishing and swimming. It was not different from any other time he was with us.”

Well, it was different one afternoon. Gonchar asked Malkin about the dedication.

https://youtu.be/RR8V88ClAtw

“He said, ‘Why talk, just watch (the) video,’” Gonchar said, laughing.

“But Evgeni was saying that he had to give a speech if he won and how he thinks everything’s been said when he won the other awards. He was telling me he just felt like he wanted to say something else. But he did not really prepare another speech. He wasn’t thinking. He was feeling emotions. It just came out.”

And that is as far as Gonchar allowed Malkin to go with the conversation about the Hart Trophy dedication.

“He was getting very emotional,” Gonchar said. “I was emotional, too. So we started talking about something else.

“We’re still Russian, I guess.”

Geno finds a friend One afternoon in August 2012, Evgeni and I walked through the Kremlin’s grounds with a photographer. The idea was to get some photographs of Malkin walking near historic sites that were a quick hop from his Moscow apartment. We would consider these for photos for the cover of his authorized biography.

During those couple of hours, Malkin started feeling his sweet tooth and stopped by a street vendor’s ice cream cart. A boy approached. Malkin offered to buy him a cone. The boy accepted.

As Malkin and the boy chatted, a woman hurried to the reigning MVP of the NHL. She appeared to scold the boy, then Malkin. In an attempt to calm her — or at least explain himself — Malkin motioned as though he would to pose for a ceremonial faceoff. He then mimicked shooting a puck with an imaginary stick. As he did this, the boy pointed and repeatedly shouted “Malkin!” but the woman remained defiant.

She grabbed the boy’s ice cream cone and handed it to Malkin. She left with the child’s hand in hers.

Malkin smiled as he rejoined our group. I asked what had happened. He explained that the woman did not want to spoil her son’s dinner. I suggested he track them down and explain who he was.

“I did,” Malkin said. “I say, ‘I’m Evgeni Malkin!’ She (did) not care. Maybe if I was Sid.”

Malkin waited a beat. His timing revealing the comedian he could have become had he not been born to do this hockey job.

“Sid (does) not eat ice cream,” Malkin said. “It’s why he’s (the) best player.”

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sidney Crosby opens up about the Golden Goal, 10 years later

Feb 28, 2020 (x)

LOS ANGELES — Sidney Crosby is capable of so many wonderful things, on and off of the hockey rink, that seeing him struggle with anything is almost curious. One thing Crosby has never mastered is the ability to be introspective. Maybe he’s no good at it, or perhaps he’s too humble to ponder his considerable greatness.

Some occasions are more poignant than others, however. Today marks the 10th anniversary of the Golden Goal, when Crosby beat Team USA in the Olympic overtime classic in Vancouver, triggering Canada’s golden era of international hockey while subsequently keeping American hockey from toppling its biggest rival.

Crosby let down his guard on the subject of his most famous goal in an interview with The Athletic following Penguins’ practice Thursday in Los Angeles. One thing is quite clear: Crosby is well aware of the importance of that goal.

“I remember the stories I was told,” he said. “In terms of goals that I’ve scored or moments that I’ve had, yeah, it was the biggest one. The reaction around Vancouver and around Canada, it’s something I’ll never forget. What I remember most is all these stories from buddies of mine, friends of mine, people in the community. Just so many different people that I’ve met. So many people have told me where they were when they were watching and when the goal went in. It was so cool at the moment it happened, to be a part of it, and to experience it. And I’ve heard all of these stories. I actually really like hearing them from people.”

As fate would have it, Crosby’s Penguins will take on Ryan Miller’s Anaheim Ducks tonight at Honda Center. A decade ago, they met in one of the most famous games in hockey history. Miller was named tournament MVP for backstopping upstart Team USA to overtime of the Gold Medal Game, but it was Crosby who had the last laugh, receiving a pass from Jarome Iginla and quickly whipping a shot between Miller’s legs.

The pressure To understand the pressure that Crosby felt that day is to understand what hockey means to most Canadians. It is their sport. The Olympics provided their stage and also the ultimate opportunity for the United States. Canada has had many challengers over the years, and one could argue Russia was the head of the hockey world during the Red Army’s reign.

Canada, though, has been the king of the hockey world for a while. By 2010, the Americans were making a legitimate push to take the crown. Young stars like Kane, Parise and Phil Kessel were pushing American hockey to new heights and, earlier in the Olympics, Team USA beat Canada, causing national unrest north of the border.

“That team was good,” Crosby said. “Really, really good.”

Crosby was 22 and fresh off of leading the Penguins to a championship in 2009. At the time, there was almost an invincible, preordained feeling around Crosby. He had lived up to the hype, and then some. He was the world’s best hockey player, already a Stanley Cup winner. The concussion drama that would torture him was still a year into the future. Canada couldn’t lose, many theorized, because Crosby wouldn’t allow it to happen.

Team Canada then lost to Team USA and looked mediocre at times during the fortnight. Crosby failed to dominate in the Olympics the way many had expected and endured trouble clicking with any linemates. The pressure mounted on him the more he failed to produce flashy numbers.

“It was real pressure, too,” said Crosby’s agent and friend, Pat Brisson. “Very real.”

So, how did Crosby deal with it?

“I’ve known Sidney since he was 13, 14 years old,” Brisson said. “Here’s the thing about him: He wants pressure. He wants things to be difficult. The more pressure there is and the higher degree of difficulty there is, the better he plays. Since the time he was a boy, there’s always been an expectation that he’s supposed to be the best and that he’s supposed to produce more team success than other players.”

Even for someone who thrives under pressure, this was a different variety of mental demand.

Did he rely on Brisson? His parents? His friends?

Not really, as it turns out.

“Well, it was a lot of pressure,” Crosby said. “It was for sure. It was my first time playing in the Olympics. When you’re a hockey player, it’s a big deal. When you’re a hockey player from Canada and the Olympics are in Canada, it’s a much bigger deal because you know that, even if you play in more Olympics, you’re never going to play in the Olympics in Canada again. This was it. This was the chance to win it all on Canadian soil. Because of that, yeah, there absolutely was a different kind of pressure and I did feel it.”

Crosby didn’t succumb to it, nor did he reach out to anyone during this time. Instead, he kept it all inside. It was by design.

“I grew up with pressure from the time I was young because of the expectations I was dealing with,” he said. “Those people (Brisson along with parents Troy and Trina) were always there to support me, honestly. And I appreciated it. But it was something I needed to go through on my own. I needed to learn. I had already been to the Cup final twice and won it the second time. That was very helpful. But this was a different kind of pressure.”

The people closest to Crosby were there if he needed to chat, or to vent, or to listen to advice.

“And he knew that,” Brisson said. “But he wanted to learn how to deal with all of that pressure on his own. That was a big thing for him. He had seen a lot for 22, but he was still only 22. But he just wanted to learn to deal with it all by himself. You know, he has ice water in his veins. He always has. That pressure is what makes him tick. The harder something is, the more challenging it becomes, it gives him more juice. It gives him more fuel. Dealing with pressure, and thriving from pressure, is in his DNA.”

Marc-Andre Fleury was a backup goalie for Team Canada during that tournament.

“When the games get bigger and when there is lots of pressure, Sid always has a way of coming through,” Fleury said. “Even then.”

The goal Crosby broke down the play in great detail. He had just taken the ice and initially attempted to break through the American defense during the four-on-four action to no avail. It wasn’t a great overtime for Crosby initially, as he twice turned the puck over in the early going. Everything changed on his final shift, though. He located Iginla along the boards and belted out the iconic “Iggy” demand that saw the pass delivered to Crosby, who was 22 at the time.

Shooting the puck, as it turns out, was not Crosby’s immediate plan.

“For a second,” he said, “I actually thought about taking the puck to the net and going to the backhand. That was my first thought.”

This makes perfect sense. No one uses his backhand more than Crosby, especially in big moments. It’s his comfort move. However, Zach Parise, who had tied the game late in the third period to force overtime, was in defensive position in the slot. Crosby saw this out of the corner of his eye and didn’t have an opening to cut toward the net on his backhand side.

“At that point, I had to tell myself that it was overtime,” Crosby said. “In that situation, you really don’t want to pass up an opportunity. And I figured that, since I didn’t really have a great angle there, my best chance was probably to get the puck away as quickly as I could. Honestly, it was pretty much a reaction. It’s not like I was picking a spot or anything like that. I really wasn’t. I just thought the key for me was to get the shot off as quickly as I possibly could.”

Brisson was sitting directly behind the net where the goal was scored.

“I’ll never forget where I was,” Brisson said. “I’m Canadian. But I’ve also worked in the U.S. for a long time. I had friends and clients on both teams. Sid. Jonathan Toews. Patrick Kane. So, there were so many mixed feelings. But being that the game was on Canadian soil, I really thought it made so much sense for Canada to win. I was hoping for that. You didn’t want to miss that moment when the goal was scored, no matter who scored it, because you knew it would go down as a famous moment. It was a very special ending and it was only fitting that Sid was the person who got the goal.”

It is easily one of the most famous goals in hockey history. Young and old, everyone has something special to say about it.

“It was quite the celebration,” said Patrick Marleau, Crosby’s new teammate. “We all flew off the bench. It was quite a celebration in Canada.”

The brewing rivalry USA Hockey remains a legitimate power in international hockey and young players such as Auston Matthews and Jack Eichel have only served to give the United States a new wave of talent.

The Golden Goal served as a plateau for USA Hockey, though. It also catapulted Canada to a different stratosphere of dominance. The Canadians would go on to win the 2014 Olympics on Russian soil with Crosby serving as captain. Then, in the 2016 World Cup of Hockey in Toronto, Crosby was easily the tournament’s dominant figure and rightfully voted tournament MVP as Canada again emerged with a championship.

Had Crosby not scored the Golden Goal, one can’t imagine how that may have changed things for Team Canada and Team USA. Crosby, whose competitiveness is the stuff of legend, used a defeat from years earlier as inspiration.

“When I was 16, we lost to the Americans in the world junior championship game,” he said, referencing the 2004 tournament. “And it all felt so similar. We were the favorite and were dealing with a lot of pressure. We took the lead. Then they came back and beat us. So, it all felt very familiar and I remember thinking about it.”

Crosby acknowledges that the historical ramifications of the game weren’t at the forefront in his mind.

“It really didn’t occur to me at the time,” he said. “I was just happy we won the game, to be honest. The United States was so good and it took everything that we had to beat them. That’s all I was thinking about. Not until later do you sit back and think about other stuff.”

The legacy Crosby is 32 now, a decade removed from being the precocious superstars who, on that Sunday afternoon in Vancouver, appeared about as invincible as a hockey player can be. Since then, much has changed. Crosby nearly lost his career to concussions and then saw his Penguins endure a series of frustrating postseason losses.

The aura of invincibility was gone.

Then came two more Stanley Cups and his sensational performance at the World Cup of Hockey. Crosby remains the world’s most famous player and arguably its best. The phenom now is revered for his ability to dominate into his 30s.

One thing hasn’t changed: Crosby still wants more Olympic glory. NHL players weren’t permitted to play in the 2018 Olympics as Gary Bettman remains quite opposed to his players participating in the Olympics. Crosby isn’t the outspoken type, but he’s not happy about the controversy that has kept NHL players from the Olympics. He knows only so many chances remain.

“Definitely I’d like to play in them again,” he said. “Any opportunity to play in the Olympics, no matter where they’re being held, is always going to be a big deal for me. It’s an unbelievable opportunity. We all enjoy that opportunity. Everyone wants to play on that stage.”

Brisson is hopeful his most famous client will get one more opportunity to earn his third gold medal.

“Sid and I talk about this all the time,” Brisson said. “The players all want to go, and Sid is no different than anyone else. It’s great for the NHL. The players want it. And you know what? Most of the owners do, too. As long as the IOC takes care of things financially, of course the players want to go. It’s no different than if you were running ‘Cirque du Soleil.’ If your artists and architects are willing to perform in China, isn’t that a good thing for Cirque du Soleil? It’s not different, and Sid wants to be there again.”

Few artists in the game’s history can paint a magical scene quite like Crosby. Maybe he’ll get his chance to return to the Olympics one last night. He’ll have a difficult time producing the magic of 10 years ago today.

“It was a special time in my life,” Crosby said.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The untold stories of Sidney Crosby, behind the scenes, as he turns 32

Aug 7, 2019 (x)

It’s probably time to consider retiring the “Sid the Kid” nickname as Sidney Crosby turns 32 today.

One of the great things about Crosby, though, is that he handled himself as an adult from the time he arrived in Pittsburgh as an 18-year-old.

I’ve covered him for a decade, which has given me a different perspective of Crosby from behind the scenes, when the cameras are off. The polished, thoughtful gentleman that you see on camera isn’t phony. Crosby really is a champion in the game of life as well as in hockey.

If you’ve read my mailbags and Q&As over the years, perhaps you’ve already come across some of these tales. Nonetheless, they’re worth telling or, in some cases, re-telling. In an era where athletes often make headlines for truly horrendous reasons, Crosby has always conducted himself as a role model.

The most frequently asked question I receive is inevitably, “What’s Sid really like?” Hopefully this will help answer that question. Here’s a look at 10 Crosby moments I’ve witnessed over the years, some of them larger than life, and some of them simply serving as subtle reminders that the Penguins’ captain is has never been changed by that nine-figure bank account.

March 22, 2010 — The Penguins had just lost to the Red Wings, 3-1, at Joe Louis Arena. It had a big-game feel because those two teams had met in the Stanley Cup final the previous two seasons, and there was a sense they could meet again, which, of course, never happened. One month earlier, for historical perspective, Crosby had won the Olympic gold medal game in overtime.

A group of reporters stood outside of the visitor’s locker room that night in Detroit. Standing beside us was none other than Gordie Howe, who had a picture in his hand. The picture, it turns out, was from the Olympics, one that showcased Crosby celebrating his game-winning goal against the United States. Howe walked directly to Crosby. They shook hands, and then Howe said, “I need your autograph on this.” Crosby looked uncomfortable and said, “You’re Gordie Howe. You don’t want my autograph.”

Howe responded, “I sure as hell do.” Crosby doesn’t look overwhelmed very often, but he almost did at that moment. He was very much in awe of Howe and has a healthy respect for the all-time greats. After signing the picture, Crosby shook Howe’s hand again.

Crosby then looked at the group of people watching.

“When he shakes your hand, it feels like your hand is going to break,” Crosby said. “God, he’s still strong.”

March 2, 2012 — The Penguins had just practiced in Denver and would play there the following day. Crosby had returned from a concussion, but made it through only eight games before enduring more symptoms.

He was skating with the team again by this time and was planning on returning to the lineup in a couple of weeks. It was pretty clear he was dealing with all sorts of emotions during the concussion. He had been scared he would never play again, concerned that his life could be permanently impacted, bored, frustrated and everything else imaginable.

By early March, he was symptom free. And he was getting a little angry. In Denver at altitude, Crosby decided to test himself. He was, by anyone’s estimation, the best player on the ice during practice that day. And it was a long, fairly grueling practice. But his work was just beginning.

While his teammates left the ice, conducted interviews, showered and walked back to the team hotel, Crosby was still on the ice, giving himself the ultimate, high altitude test. It almost looked like he was punishing himself. A few people were in the building watching, and they were starting to look uncomfortable just from watching the workout he put himself through.

When it was finally, thankfully over, Crosby stayed on one knee for extended period of time, lost in his thoughts and nothing else. I believe that was the moment when he knew the hurdle had finally been cleared.

April 22, 2012 — The Penguins had just been dismissed, with conviction, by the Flyers in the first round of the playoffs. Entering the postseason as the Stanley Cup favorite, the Penguins were embarrassed by their biggest rival.

Crosby hardly played poorly in that series, having just returned from his health issues to record eight points in six games. But had been outplayed by Claude Giroux and the Penguins had lost their minds, and the series, in one of the low moments in franchise history.

The locker room following Game 6 was a particularly somber one, as you might imagine. Crosby and Jordan Staal were the final players to leave the room. Staal knew he would be traded that summer, that his time with the Penguins had come to an end. He sat beside Crosby, the two of them barely able to speak.

In the distance, Crosby could hear the Flyers celebrating. The look on his face told quite a story. He’s never made it a secret that he doesn’t care for the Flyers. Losing to them had a big impact, and the look on his face indicated that he never again intended on losing a playoff series against them. He could have left the room but instead just sat there, taking in the noises and the celebrations. You could see it fueling him. So far, he’s met them once and recorded 13 points in a six-game series victory in 2018.

Nov. 20, 2012 — The true essence of Crosby was on display during the lockout. He was 25, right in the heart of his prime, and was finally feeling healthy after missing 101 games — not including a playoff series — during the previous two seasons. All he wanted to do was play. And he couldn’t.

During this time, Crosby and about 10 of his Pittsburgh-based teammates practiced daily at Southpointe. On this particular day, when his teammates were done for the day, Crosby stayed on the ice for an additional half hour. There were hundreds of pucks on the ice, two nets and the greatest hockey player in the world. He stayed on the ice for 30 minutes after they were gone. When practice was over, the methodically skated the two nets off the ice and into a storage room. He then corralled the pucks into the center of the ice, sat on the frozen surface and placed each puck into a bag. This became his routine on a daily basis. There was something sad about watching Crosby carry nets off of the ice each day. There was also something impressive about it. He’s no diva. It became his custom, day after day, to stay on the ice for longer than anyone else, and to save the maintenance staff in the building the extra work of putting everything back where it belonged.

Dec, 10, 2012 — Team officials weren’t allowed to be at Southpointe during the lockout. Those workouts were for players only. No media relations officials allowed. So Crosby decided to serve as his own media relations person. Really.

I got a phone call from Crosby on the night of Dec. 10. It was a Monday.

“Hey Josh, I know I told the media we were going to practice at Southpointe tomorrow. But something came up so we’re not going to be able to now. I’m really sorry about it. I would feel awful if anyone drove to practice, and expected us to be there. So if you could please let everyone know that we won’t be there tomorrow, I’d really appreciate it.”

March 25, 2013 — The Penguins were thinking about making a trade deadline splash: Jarome Iginla. Following practice, some of the team brass wanted to have a meeting and wanted Crosby to be involved. I don’t know what the meeting pertained to, but I’ll guess Iginla was one of the topics involved.

Ray Shero was hovering around the locker room after practice. Some coaches were around. Dan Bylsma was looking for his captain and finally said, “Does anyone know where Sid is?”

No one knew, in fact. Crosby almost always talks with reporters following practices but wasn’t around the locker room that day. Nothing to be concerned about. Maybe it was an equipment issue. Maybe he didn’t feel well. Maybe he was busy. These things happen.

A quick walk around the corner adjacent to the locker room told the story. Crosby was on his hands and knees, skates still on, having a conversation with a boy in a wheelchair that probably spanned 30 minutes. This is a common sight. Crosby always goes out of his way to not only greet people who deal with health struggles, but to actually listen to them and spend time with them. I see it all the time, but you never stop appreciating it. It’s not for show. It’s totally genuine, Jarome Iginla meetings be damned.

Jan. 11, 2014 — The Penguins had just won in Calgary. And it was cold. Really cold. And windy. Alberta winters aren’t usually pleasant, after all.