Text

Tribute: Peter Hutton’s Haikus

August 30 - 31, 2017, Close-Up Cinema, London

Rattis Books and Close-Up Cinema pay tribute to the visionary artist Peter Hutton, one year on from his passing. Presenting the first substantial screening of Hutton’s works in London in a decade, this two-night programme, introduced by writer, critic & curator Ed Halter, focuses on a cross-section of the film-maker’s intimate and lush portraits of urban, rural and marine environments.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Expanded Cinema : Tyburnia

Thursday, 13 July 2017, 9pm, The Old Church, London

A live film soundtrack by Dead Rat Orchestra, James Holcombe and Lisa Knapp

Inaugurating the 2017 Tyburnia Tour, Rattis Books is pleased to present the opening iteration of Tyburnia live film and soundtrack performance by James Holcombe, Dead Rat Orchestra and Lisa Knapp. ‘There had been a hanging tree at Marble Arch called the Tyburn Gallows. For over 700 years this district was regularly used as a site for the execution of men, women and children, and its estimated that over 40,000 people were killed there. In addition to a gallows there was a gibbet and whipping post, and a large fixed stone, which is marked on John Rocque’s 1746 map of London with ‘here soldiers are shot’, presumably for desertion. The name Tyburn (or Tyburnia) comes from the ‘lost’ river Tyburn which traversed the area, [..] a site where the desires of the State, Church and Capital, to discipline and punish, were played out on a regular basis. The sheer horror of what lay in the archive prompted [James Holcombe] to start to make a film and explore the notion that the ‘lesson’, as Peter Linebaugh describes it in his book The London Hanged, is still being taught: that money, capital, and the power structures which surround them are still just as determined to protect their interests in this period of late capitalism as they have been throughout history.’ [1]

Shot on 8mm and 16mm film, the work drifts through artefacts associated with the Tyburn; reliquaries housing the remains of catholic martyrs, body parts preserved by surgeons, the bell that tolled on the eve of executions, and the eventual resting place of the gallows themselves. For this iteration, James Holcombe will be utilising multiple film projectors for an expanded cinema performance of the work featuring physical manipulation, optical distortion, and live destruction of film. Dead Rat Orchestra in collaboration with award winning multi-instrumentalist and singer Lisa Knapp, will perform a live soundtrack featuring songs composed by or for those condemned to 'dance the Tyburn jig', bringing a new understanding to broadside ballads that have become a staple of folk music, but here presented in close association to their original context.

The shadow of the Tyburn Tree extended well beyond London, with gallows, whipping posts and gibbets in many market and county towns. To explore this rich and melancholy history Tyburnia will be performed as close to the location of various regional gallows as possible.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Marattam (Masquerade/Faces and Masks, 1988)

24 February 2017, Close-Up Cinema, London

Mythical Poetry : The Cinema of Govindan Aravindan

Our retrospective 'Mythical Poetry: The Cinema of Govindan Aravindan' closes tonight with his fascinating 'dance-film' Marattam (Masquerade/Faces and Masks, 1988) that draws it's inspiration from both Kathakali and Theatre, a film that almost is an aberration in Aravindan's oeuvre for it's distinct narrative and visual style, a bridge film if you may, that can connect Uday Shankar's 'Kalpana' with Jayaraj's 'Kaliyattam'.

Panicker’s one-act play deals with the relation of identification between an actor and his or her role. Aravindan put the stress on the relations between the viewer and the actor/role dualities. The action takes place on the eve of the last act of the Kathakali piece Keechakavadham (The Killing of Keechaka). The events surrounding the performance uncannily echo events in the play. "...the film can be divided into three parts. Each part is a version about the murder of Keechaka. The first version is told by Koipattiri who plays the role of Valalen [...] and acts out how Koipattiri kills Keechaka. The second part is the story told by the wife of Koipattiri. She tells the police that she has committed the murder. The third part of the story is told by the chorus. They killed the artist in Kelu because Kochashan (tutor) from the 'Kalari' (school) tells them to do so. All the three episodes are rendered differently. [...] I have kept a continuous movement while fusing the three episodes. Most of the shots used in the film are either crane shots or trolley shots. There is no still shot other than that of the policeman who is in a way, external to the story."

0 notes

Photo

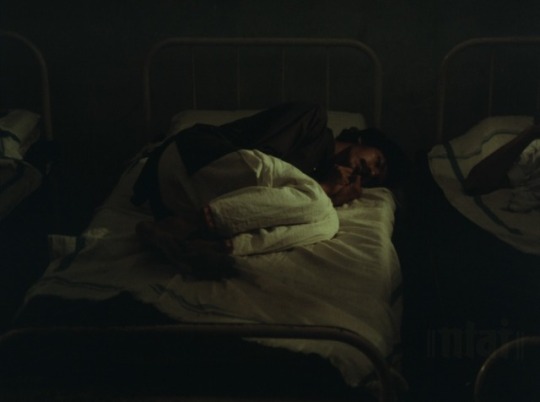

Chidambaram (1985)

Thursday 23 Feb 730 pm Close-Up Cinema, London

Mythical Poetry : The Cinema of Govindan Aravindan

Chidambaram is the most popular of Aravindan’s films. “Unfolding in exquisitely photographed poetic rhythms and coloured landscapes, this is the simple but cynical tale of Muniyandi (Srinivas), a labourer on the Indo-Swiss Mooraru farm in Kerala. He brings a wife, Shivagami (Smita Patil), from the temple town of Chidambaram. She befriends Shankaran (Bharath Gopi), the estate manager and amateur photographer with a shady past. Their friendship transgresses the hypocritical but deeply felt behavioural codes the local men inherited from previous social formations: i.e. that women are to be denied what men are allowed to enjoy. The tragedy that ensues (Muniyandi’s suicide, Shankaran’s descent into alcoholism and Shivagami’s withering into a worn-out old woman) condenses the tensions between socioeconomic change (as tractors and machinery invade the landscape) and people’s refusal to confront the corresponding need to change their mentality. The tension is, however, most graphically felt in the way Shivagami’s life-force is extended into the naturescape, which is shot around her with garish colour (e.g. purple flower-beds) suggesting that the very nature of Kerala’s beauty and fertility, as she represents it, has been irredeemably corrupted from within. The film then shifts to the equally oppressive cloisters of the Chidambaram temple, as Shankaran and Shivagami meet once more: he is there to purify himself through religious ritual while she is now employed to look after the footwear of devotees and tourists. The nihilist film ends with a rising crane shot as the camera can only avert its gaze and escape, tilting up along a temple wall towards an open sky.” (Ashish Rajadhyaksha & Paul Willemen, Encyclopaedia of Indian Cinema, 1994)

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kummatty (The Bogeyman, 1979)

Friday 10 Feb, 2017, 730pm GMT, Close-Up Cinema, London

Mythical Poetry: The Cinema of Govindan Aravindan

As in Esthappan (1980), children make their presence strongly felt yet again in Kummatty (1979). Another half mystic half real figure like Esthappan, the Bogeyman recalls the fantastic masked characters from Tomu Uchida’s Mad Fox (1962). Japanese film critic and historian Tadao Sato who had previously written on Tomu Uchida’s films was a fervent admirer of Aravindan. He was particularly fond of Kummatty and showed the film to Shohei Imamura who was ecstatic about the film. He was also instrumental in organizing what was the first comprehensive retrospective of his works at the Fokuoka Film festival in 1991. Working with fantasies and folktales, Kummatty is a fable-film where the protagonist evokes the arrival of spring. In Aravindan’s films the relationship of man and nature acquires various dimensions, while in Kanchana Seeta the moods of nature affirmed Sita’s presence to Rama, here Kummatty himself is the harbinger of Spring. In one of the truly breathtaking sequences in the film, Kummatty has transformed the children into animals who then dance around him in the vast expanse of an arid land. This is also the film where Aravindan’s theater and dance background cast an unmistakable shadow. An integral film in his oeuvre.

0 notes

Photo

Pokkuveyil (Twilight,1981)

Sat 11 February 2017, 7:30 pm, Close-Up Cinema, London

Mythical Poetry : The Cinema of Govindan Aravindan

In Pokkuveyil (Twilight,1981), Aravindan further reflects upon the human condition in the modern society. It is a leisurely film with a characteristic slow pace that is musically structured. In Aravindan’s own words: “The film progresses in the musical structure of 1,2,3,4. 1,2,3,4…First, you see the house, then the homely Nisha, the sportsman, Joseph, who is a revolutionary and then again the house, the girl…the repetition of shots in that order. As the girl takes leave, this structure changes. The pace becomes faster. I thought this might help to bring out the life and movements of the protagonist Balu better.” Like in Uttarayanam (1974), Aravindan remains skeptical of society and its ways at large . The hallucinations of a young man as his connections with the world slowly disintegrate is juxtaposed with poetic long takes and pans. The name Pokkuveyil meaning twilight, also suggests the mood of the film, the film is marked by a certain sense of eventuality, entrapment that contrasts Uttarayanam which implies ascent (of the Sun). Pasolini once remarked about Antonioni that he identified his own delirious aesthetic vision with the vision of a neurotic woman. The same rings true for Aravindan and his protagonist Balu.

0 notes

Photo

Amrit Gangar on Aravindan's Kanchana Seeta/Golden Seeta and the idea of ‘Cinema of Prayoga’ "Kanchana Sita (1977), by G. Aravindan, was made 20 years after Pawan Putra Hanuman and it’s also from the Ramayana. Aravindan was one of the finest minds in Indian or even world cinema, and this film is his interpretation of the Uttara Kanda, the last segment, of the Ramayana, where the Lord Ram after defeating Ravana and returning with his wife Sita from Lanka, banishes her from his kingdom, unknowingly wages a war on his twin sons, and finally surrenders himself to the waters of the river Sarayu. The film opens with Ram and his brother Lakshman travelling through the Dandaka Forest to attend a religious feast, and Ram is acutely conscious of Sita’s presence, even though she’s not there. In fact, in Kanchana Sita, the titular character is physically absent from the film throughout. Instead, Aravindan portrays the mythical Sita of flesh and blood through ripples on a river, through a breeze, through rustling leaves, or through prakriti (nature). Sita is suggested here, not shown. She is suggested through what, in Sanskrit, is called ‘vyanjana’, or the suggestive aesthetics of the film. From this seed of an idea—exploring vyanjana through prakriti—Aravindan goes on to explore the ancient philosophy of purush (man) and prakriti, twin concepts that form the basis of our understanding of our selves. Also, he explores the idea of the relationship of the male, purush, with the female, prakriti. This latter thought is one Aravindan might have gotten from the Sankhya Yog, one of our oldest scriptures. Kanchana Sita creates a spatial as well as temporal environment which envelops the viewer in prakriti, via the wind, the movements of trees and leaves and the river. Spatially, you see Sita who is pristine— as nature, as a gentle breeze, as a bhav (a feeling or thought) of being and becoming. Also, you see her temporally, because you feel her presence all the more in time that she is absent. This feeling is intensified by the fact that there are few words in the film. It has hardly any dialogues, which is another one of its strengths: Kanchana Sita doesn’t need the theatricality of dialogues to create cinema. To shoot this, Aravindan went to Andhra Pradesh in the tribal areas where the Chechu—tribals who believe they are the direct descendants of Ram—live. He didn’t use the conventional imagery, such as regal headgear, to portray Ram and Laxman. Instead, he portrayed them as tribals, something which is unusual for our cinema, and a political statement of sorts. This is how we retrieve from our traditions an understanding of modernity— what I call Prayoga. The Cinema of Prayoga also requires that an artist’s work be in natural or sahaja harmony with his or her svabhāva, or temperament. Here we find Aravindan’s cinematography to be very close to, very congenial with, his svabhāva, like Phalke’s work had been with his svabhāva. The advantage of this is that it imbues the film with an uncanny sense of intuition. The result is an intensely poetic and profoundly contemplative work that is felt like a bandish of a raag— especially the strong sensuality that Aravindan explores in the film through prakriti. In the end, Ram submerges himself in the river Sarayu, to be with prakriti, or to be with Sita. This, I would say, is a Prayoga interpretation of the epic." http://thebigindianpicture.com/2013/06/their-experiments-with-truth/

0 notes

Photo

London remembers Aravindan: Reliving some of his much-loved films 'A quarter of a century since his sudden demise, London based Rattis Books and Close-up are presenting the first European retrospective of the great filmmaker from Kerala, G Aravindan. Their programme offers rare opportunity to discover six of his most important works, known for their “distinctive look, sparse naturalism, silences and long shots with darker shades of grey in b/w films”.' http://filmindiaglobal.com/2017/01/london-remembers-aravindan-re-living-some-of-his-much-loved-films/

0 notes

Photo

"The title of the cartoon serial by Govindan Aravindan, Cheriya Manushyarum Valiya Lokavum, translates to Little Men and the Big World. It ran on the last page of the Mathrubhumi Weekly for 13 years from 1961 to the end of 1973. I shall try and show how Aravindan elevated the cartoon into a story-telling narrative, which is what we call the graphic novel today. Over the years, the weekly serial scaled up into something like a novel. Not just because it was habitually read like any other cartoon feature that gave you updated accounts of social life through a fixed set of characters. Aravindan’s characters aged organically like the reader, and they had personal and familial tales to tell as well. This business of ageing with time was tried out much later more famously in the mid-1970s in the American comic strip Doonesbury by Gary Trudeau." https://thereel.scroll.in/804838/you-know-aravindan-the-filmmaker-meet-aravindan-the-cartoonist

0 notes

Photo

[Photos] The enduring magic of G Aravindan’s cinema

by thereel.scroll.in

...film festivals will hopefully take note of this programme and make a similar effort to re-introduce Aravindan to both older loyalists and younger cineastes."

https://thereel.scroll.in/828403/photos-the-enduring-magic-of-g-aravindans-cinema

0 notes

Photo

London to host the first European retrospective of Malayalam artist-filmmaker Govindan Aravindan The first European retrospective of the Malayali artist-filmmaker Govindan Aravindan will be held in London from 3 to 24 February.... http://en.southlive.in/film-news/2017/02/03/london-to-host-the-first-european-retrospective-of-malayalam-artist-filmmaker-govindan-aravindan

0 notes

Photo

Stephen (Esthappan, 1980)

4 - 17 February 2017, Close-Up Cinema, London

Mythical Poetry : The Cinema of Govindan Aravindan

After Kanchana Seeta (1977), the mythical dimension of Aravindan's cinema acquires a quasi-real, quasi-mythical character in Esthappan (1980). The protagonist of Esthappan hails from the Latin Christian fishermen community in Kerala. An enigmatic figure defying spatiotemporality, like many others in Aravindan's films resides at the periphery of society. In Aravindan's own words, ..."He was a very ordinary man. You understand Esthappan only through the stories people relate about him. There are people who tell one story in many different ways. In the film there is one person giving two stories of the same event. At this rate we don't know what is real and what is mythical. The issue here is which of the stories about Esthappan is right. Perhaps all of them are right, perhaps all are wrong." The film ends with a mythical dance play that embodies the essence of Esthappan which Ashish Rajadhyaksha identifies as Chavittu Natakam, a form derived from Portuguese passion plays that arrived on the Indian shores in the 16th Century with the arrival of Portuguese missionaries in Kerala. A drama derived from one such passion play, Jesus Cristo's Auto da Paixão influenced Manoel de Oliveira's Acto da Primavera (1963). Part of our Mythical Poetry: The Cinema of Govindan Aravindan at Close-Up Cinema.

0 notes

Photo

Golden Seeta (Kanchana Seeta, 1977)

3-12 Feb 2017, Close-Up Cinema, London

Mythical Poetry : The Cinema of Govindan Aravindan

Aravindan's film Golden Seeta (Kanchana Seeta, 1977) based on C N Sreekantan's play and the Indian epic Ramayana is perhaps his most enchanting film. The sparsity of dialogues, the essence of Seeta nurtured through the moods of nature with evocative musical notes that complement the visuals - a cinematic treatise on the harmony and discord of man and nature, reminding us of the juxtaposition of Vartanov's poetic images with Vivaldi's compositions in Artavazd Pelechian's 'Seasons of the year' (1975), the tribals enacting the mythical figures all married to Shaji N. Karun's inspired cinematography produce a unique poetic experience that concludes with Rama's suggestive suicide as he walks into River Saraya under the setting sun, a suggestive communion with Seeta. Aravindan's casting of rustic tribals as mythical figures, the Rama Chenchus from AP, inspired by sculptures have a strong physical presence, their faces exude a certain pre-industrial innocence like the Palestine children whom Pier Paolo Pasolini met while scouting location for The Gospel according to St.Matthew (1964) or the villagers who enact the Passion of Christ in Manoel de Oliveira's Acto da Primavera (1963). The opening film of our retrospective Mythical Poetry : The Cinema of Govindan Aravindan screening at the Close-Up Cinema, London.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

A self-portrait by G.Aravindan - artist-filmmaker in spotlight as part of our February 2017 film programme Mythical Poetry : The Cinema of Govindan Aravindan hosted by the Close-Up Cinema, London

0 notes

Photo

Golden Seeta (Kanchana Seeta, 1977)

Mythical Poetry : The Cinema of Govindan Aravindan

"There are some specific reasons for deciding to have sparse dialogues in Kanchana Seeta (1977). One, this episode taken from Ramayana is familiar to all. Two, Ramayana is not a supernatural reality for us, as it is ingrained in us. It is therefore not necessary to educate people about the film through lengthy dialogues. C N Sreekantan had made clear the prakrithi-purusha notion in Ramayana. I did not think that Seetha should come in the film in the form of a woman. That is why Seetha appeared in the film as prakrithi (Nature) and Prakrithi is a character in the film. I felt I could make the film without dialogue. Rama committing suicide - (I still feel it was - self-immolation) had haunted me very badly. With all these, my Kachana Seeta became very different. Words were required only for very essentials. The dialogues, which I used, were from C N's play. The doubt I had then was whether my Rama and Lakshmana (as they were ordinary people) could use such an eloquent Sanskritised language. I did not think that Seeta should come in the film in the form of a woman. That is why Seetha appeared in the film as Prakrithi (Nature) and Prakrithi is a character in the film. When the emotions of Seetha like pain, sadness, joy, and equanimity are manifested through the moods of Prakrithi, dialogue becomes redundant. [..] The Rama of Kanchana Seeta exudes the strength and vitality of our sculptures. He is not just a plain frontal image. The wandering tribals we encounter here and there with their medicines also share this quality. I enquired and found that these people are settled in villages near the Godavari River. Apart from this they also believe that they belong to the same race. That is why I cast two of them in my film. [..] I have deliberately not given a super human quality to Rama and Lakshmana. Only when they interact with Nature do they rise to the levels of God and go beyond the ordinary. Otherwise they would have been the same as anybody else. [..] The Valmiki of my film is not an ordinary tribal; he is a visionary and a poet. So I have given him an appropriate form and beauty - a form, which pervades the beauty and purity of the soul all around. Valmiki, the poet, stands up to Rama on matters of principles. The poets of all ages should be questioning the injustices of their times. By the way, the dubbing for Valmiki was done by John Abraham." - G. Aravindan on Golden Seeta (Kanchana Seeta, 1977) - the first film of our retrospective Mythical Poetry : The Cinema of Govindan Aravindan screening this Friday 730 pm at the Close-up cinema, London.

0 notes

Photo

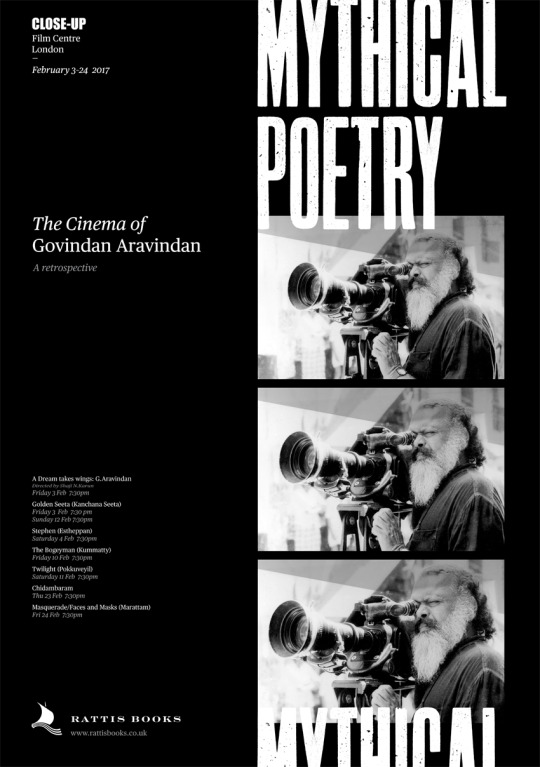

RETROSPECTIVE: Mythical Poetry : The Cinema of Govindan Aravindan

We are pleased to present the first European retrospective of the artist-filmmaker Govindan Aravindan in February 2017 at the Close-Up Cinema, London. More information here : http://www.rattisbooks.co.uk/film-programmes.html

This beautiful A2 letterpress poster has been designed by The Counter Press

1 note

·

View note

Link

"These are articles that can be deceptively hard to write. They require a lot of research which often isn’t easily accessible or in a language that you can comprehend. And then the narrative might not line up to provide an interesting story. It takes a particular kind of writer to work past these challenges and pull out the story." writes Paul Grech, Editor of Cultured Football

0 notes