reanimatrixx-blog

16 posts

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

《血菩萨》 [BLOOD BODHISATTVA]

DRAMATIS PERSONÆ

TIĀN MǓ ~ Elderly military commander. DÀ LÁNG ~ Head of the Five Poisons Sect, whom Tiān Mǔ has been waging war against for decades. SÀTǓN ~ Eldest daughter to the late Empress. BÁI SĪ ~ Youngest daughter to the late Empress; in a power struggle with Sàtǔn for the throne. TIĚ GŪ ~ Court official and Tiān Mǔ's sister. BǍ XĪ LĀ ~ European, Nestorian Christian missionary with a demonic appetite for destruction. TIĀN YÒU ~ Scholar, poet and Tiān Mǔ's son. IRON MOUNTAIN BLADES ~ Tiān Mǔ's personal guards. TIĚ YĪNG, TIĚ LIÁN, TIĚ LÍNG and TIĚ XUÈ ~ Tiān Mǔ's Daughters. HUĪ DÚ, LÁN DÚ and HĒI DÚ ~ Dà Láng's Daughters. LǏGUĀN, YÙSHǏ and JINYIWEI ~ Imperial Court Officials.

֍

[第一幕·第一场] [ACT I. SCENE I]

《铁碎骨,羽没血,双姝启神不可封之伤。》 [Iron grinds bone, feathers drown in blood, two sisters open the wound no god can close.]

[玉门国·千剑宫外。] [Yumen Kingdom · Outside the Thousand Swords Palace.]

([战鼓裂云,幕启时,白思与萨囤对峙宫阶之上。铁牛、天鹤两派弟子于阶下血战。宫门处,礼官肃立,御史执笔,锦衣卫刀出半鞘,静若石雕。] / [War drums tear at the clouds as the curtain rises, BÁI SĪ and SÀTŪN stand frozen on the palace steps. Below, their Iron Ox and Heavenly Crane disciples wage war. At the gates, LǏGUĀN officers stand rigid, YÙSHǏ scribes clutch ink-brushes and JINYIWEI guards rest hands on half-drawn blades, silent as carved sentinels].)

SÀTŪN / 萨囤 ([斩马刀啸空而过,尘暴如龙卷起。] / [Her Zhanmadao screams through air, whipping up a dust-whirlwind].) 铁牛门下! Sons and daughters of the Iron Ox! 朕即凤诏,天命在刃! I am the Phoenix's living edict, the Mandate burns in my steel! 和我一起站起来,铸就历史的栋梁! Stand with me and be forged into history's pillars! 叛龙者…… Betray me … ([刀光一闪,宫灯齐灭。] / [A blade-flash—every palace lantern gutters out].) … 九族诛尽,宫门悬颅! … And I'll hang your bloodline's skulls from the palace gates!

BÁI SĪ / 白思 ([双针剑作���翼式,冷笑。] / [Needle-swords flash into crane-wing stance, her sneer colder than moonlight].) 天命?([冷笑。] / [Laugh like cracking ice].) The Mandate? 弑亲之血,也配称凤? Can a kinslayer's hands still clutch the Phoenix's crown? 天鹤展翅! Heavenly Crane spreads its wings! ([她的双剑如振翅之羽轻颤——鹤之优雅中藏蝎之毒。她的门人齐声高鸣,宛如绢帛被利刃撕裂的尖啸。] / [Her blades shiver like pinions mid-strike—the crane's grace laced with scorpion's venom. Her faction echoes with choral crane-cries, a sound like silk tearing on sword-edges].) 重器非在冠冕,而在德行。 True power lies not in crowns, but in virtue. 尔自比狂风?不过瘈狗吠日! You call yourself a storm? A rabid dog barking at heaven! ([她的战士们的呐喊声响彻云霄——铁牛队伍摇摇晃晃,阵型散乱。] / [Her warriors' cries pierce the air—the Iron Ox ranks stagger, their formation fraying].)

TIĚ GŪ / 铁姑 ([持碧玉令,九节鞭缠腰。满场肃杀。] / [Enters with the Jade Scepter, her 9-section whip coiled around her hips. The air thickens, sharp as a guillotine's edge].) 骨肉相残之座,未雪先倾。 The throne built on sister-blood collapses, before winter's first snow can hide its sins. 今奉碎玉令,迎天母将军班师 ... By the Broken Jade Seal, I declare General Tiān Mǔ regent ... 五毒教之役,当终今日。 Her war against the Five Poisons Sect ends now. 散! Disperse! … 否则御史以刻石指铭罪,鬼神同泣! … Or the Yùshǐ's Stone-Carving Finger will engrave your crimes so deep, even gods and ghosts will wail! ([御史的一击落地——指尖击碎了大理石地板,裂开了蜘蛛网,如同下了判决书一般。] / [The Yùshǐ's strike lands—fingertips shatter the marble floor, cracks spider-webbing like a verdict].)

SÀTŪN / 萨囤 ([见玉阶旁书生所留的砚台,冷笑。] / [Spots an inkstone left by a fleeing scholar, her lips curl].) ([脚踢翻,墨泼阶如血。] / [Her boot flips it, black ink gushes down the steps like a slit throat].) 刻啊! Carve this! 让后世记得…… Let history remember … ([锦衣卫刀光映墨,凤鸣凄厉。] / [Jinyiwei blades gleam with reflected ink, their phoenix-cry a funeral dirge].) ([白思的鹤簪坠地,羽尖沾墨。] / [BÁI SĪ's crane-hairpin clatters, its feather-tip staining black].) ……铁牛将军之妹执印却不敢执刃! … the Iron General's sister clutches seals, but flees from steel!

TIĚ GŪ / 铁姑 ([举令,寒声。] / [Raising the Jade Order, her voice colder than a tomb's breath].) 刻石遗臭,万古流秽。 Let stone etch your reek, let ten thousand generations gag on your name. ([玉阶震颤,如畏其言。] / [The jade steps tremble, as if fearing her decree].) 母皇遗诏刻于玉,非书于血。 The Empress' will was carved in jade, not scribbled in traitors' blood. ([锦衣卫刀锋低鸣,似凤泣先帝。] / [Jinyiwei blades hum, a phoenix weeping for the dead sovereign].)

BÁI SĪ / 白思 ([凝视没羽,墨渍如泪,轻叹后扬声道。] / [Gazes at the drowned feather, ink seeping like tears, then her voice lifts, clear and cold].) 血缘始,血缘终。 By blood it began, by blood it ends. ([向铁姑鞠躬,腰如竹折而不断。] / [She bows to TIĚ GŪ, back bent like bamboo, unbroken].) 我臣服 ... I yield ... 非顺汝刃,乃顺天佑。 Not to your blade, but to Heaven's decree. ([白袍众退如雪崩,寂然无声。] / [Her disciples retreat like an avalanche in reverse, soundless, deliberate].) 愿鹤唳引慈母之手。 May the crane's cry guide my Mother's hand. ([此言如刃,悬于天下咽喉之上。] / [The words hang, a knife at the world's throat].) 雪退散… The snow withdraws... ([… 然寒入骨,千年不化。] / [...but frost lingers in the bones and will not thaw for a thousand years].)

SÀTŪN / 萨囤 ([斩马刀寒光隐现,似判决半出鞘。她目光灼烈,胜过大漠热风。] / [Her Zhanmadao gleams, a verdict half-unsheathed. Her gaze burns hotter than the desert wind].) 名铸剑出,不悔不归。 My name is forged in steel, my blade thirsts without remorse. ([铁牛派虽退,手不离刀。] / [The Iron Ox faction withdraws, but every finger still curls around cold steel].) 让玉门断壁 ... Let the ruins of the Jade Gate ... ([刀锋划地,裂石如骨碎。] / [Her saber splits the earth, stone shatters like a spine].) …由此断定,谁之血脉承载真凤天命! … decide whose veins bear the Phoenix's truth!

([众人退却之际,守卫扬起玉尘,五行阵于空中隐现旋转,倏然破散,恍若凤凰涅槃重生。] / [As factions retreat, guards raise jade-ash, the Wuxing symbols form then dissolve like a phoenix's rebirth from the ash].)

([幕落,唯余 --] / [The curtains close on --]) 萨囤之刀 [Sàtūn's blade] 插于玉阶 [Embedded in jade steps] 白思之羽 [Bái Sī's feather] 飘向冷月 [Drifting toward the icy moon] 铁姑的鞭 [Tiě Gū's whip] 缠着半截断诏 [Coiled around a torn edict] 上书: [which reads:] 朕死之年... The year I die... ...血菩萨现。 ...the Blood Bodhisattva comes.

֍

[第一幕,第二场] [ACT I. SCENE II]

[剑冢森森,魂灯荧荧] [A forest of grave-swords; ghost-lanterns flicker blue.]

[祖剑堂 · 地宫] [Ancestral Sword Hall · Underground Crypt.]

([战鼓渐歇,丧钟低鸣。地宫穹顶垂百剑,剑柄为碑。二十石台空置,待天母众女。青烟如蛇,盘绕尸骨未寒之刃。] / [War drums fade; funeral bells toll low. A cavern glows with yin-blue lanterns. From the ceiling hang a hundred swords, hilt-down, each a grave-marker. Twenty empty stone plinths await TIĀN MǓ's fallen daughters. Incense coils like serpents around blades still slick with death].)

([铁链声响。铁链与铁翎押阵,铁山刀卫捧灵位与佩剑次入,后随铁英、铁血。天母戎装未卸,甲上犹带草原尘沙。大狼与其女[灰毒、蓝毒、黑毒]棘链缚身。末入巴悉拉,景教十字暗芒浮动。] / [Chains rattle. TIĚ LIÁN and TIĚ LÍNG march at the front, followed by Iron Mountain Blades bearing spirit tablets and sheathed swords. TIĚ YĪNG and TIĚ XUÈ come next. Then TIĀN MǓ, her armor still caked in steppe dust. Behind her, DÀ LÁNG and her daughters [HUĪ DÚ, LÁN DÚ, HĒI DÚ] shuffle forward, bound in barbed chains. Last enters BǍ XĪ LĀ, his Nestorian cross glinting like a hidden blade].)

([众人迫大狼一族跪于五眼蟾蜍铜魂炉前。] / [The prisoners are forced to kneel before a bronze soul-brazier shaped like a Five-Eyed Toad].)

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([举碎玉令,诵咒如刃。] / [Raising her broken Jade Seal, chanting like a whetstone on steel].) 玄女兵主—— Xuánnǚ, Dark Mother of War— 开黄泉之扉。 Open the Yellow Springs' gate. ([抚剑墙,声裂金石。] / [Her gauntlet scrapes the sword-walls; her voice splits metal and stone].) 吾女今与鬼同行。 My daughters walk with ghosts now. 以刃镇幽冥。 Let their swords guard the underworld's edge. ([铁山刀卫置灵位于石台,朱砂名讳如血。无棺椁,以剑代尸。] / [The Iron Mountain Blades place spirit tablets upon the plinths, names written in blood-red cinnabar. No coffins. No corpses. Only swords to stand in their stead].) ([抚空台,甲缝渗沙。] / [Her armored fingers brush an empty plinth, steppe-dust sifting from the joints].) 祖剑冢啊… O sacred crypt ... 汝怀吾欢,亦纳吾悲。 You who cradle my joy and grief alike. 为何贪噬无厌? Why must you gorge so ravenously?

TIĚ YĪNG / 铁英 ([执刃穿魂幡,幡动如濒死之息。] / [A dagger-pierced soul-banner trembles in her grip like a death rattle].) 母亲,赐一囚破丹田。 Mother, grant us a prisoner to shatter. 以炁饲亡魂。 Let her qi feed the dead. 化其息为香。 Let her breath become their incense.

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([戟指灰毒,甲上反光如狼瞳。] / [Her gauntlet points to HUĪ DÚ, armor-scratches glint like wolf-eyes].) 取可汗长女。 Then take the Da Khagan's eldest. 草原狼种,正合燃薪。 a steppe-wolf's whelp, fit kindling.

HUĪ DÚ / 灰毒 ([颤声,气将断未断。] / [Her voice trembles, breath not yet broken].) 吾非薪。 I am not kindling.

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 ([锁链暴起,棘刺入肉。] / [Chains rattle as manacles bite into flesh].) 这也配称'道'? You call this the Tao? 这不是道。 This is no Tao. 是屠宰场! It is the abattoir! ([唾血] / [Spits blood].) 玉皇必降天罚—— The Jade Empress will curse your—

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([抬手如闸,声寒于铁。] / [A raised hand silences like decapitation].) 天道不悯豺狼。 The Tao has no mercy for wolves. 汝女之息,当饲吾殇。 Your daughter's breath will feed my dead.

TIĚ YĪNG / 铁英 ([并指为鹤喙,点向灰毒后腰。] / [Fingers coiled like a crane's beak, pressing to HUĪ DÚ's spine].) 道予炁,道夺炁。 The Tao gives qi. The Tao takes it. ([三击如钟。] / [Three strikes toll like a funeral bell].) 命门。 [Mìngmén.] ([闷响,灰毒气息骤滞。] / [A dull thud—HUĪ DÚ's breath seizes].) 脊中。 [Jǐzhōng.] ([玉裂之声,肌骨僵锁。] / [A crack like splitting jade, her body locks rigid].) 大椎。 [Dàzhùi.] ([折骨脆响,银炁自七窍喷涌,旋入魂炉。] / [A final snap, silver qi bursts from her seven apertures, swirling into the brazier].)

([炁凝'仇'字,瞬散。铁山刀卫置灰毒于碑前,形存神灭,永跪为鬼奴。] / [The qi forms the character 仇 《vengeance》before dissolving. HUĪ DÚ's hollowed body is propped before the plinths; a living ghost forced to kneel for eternity].)

TIĀN YÒU / 天佑 ([三叩入殿,额抵冷石。] / [Entering with three kowtows, forehead pressed to stone].) 母亲… Mother… ([捧纸马,声颤。] / [Clutching paper effigies, voice trembling].) 儿带冥驹,助姊远行。 I bring paper horses for their journey. ([天佑一边吟诵诗歌,一边焚烧人像。] / [TIĀN YÒU begins burning the effigies while reciting poetry].) 双蛇缠… Two snakes entwined ... ([纸灰突燃碧火。] / [The ashes flare emerald].) 无首尾 ... Neither head nor tail ... ([焚纸,灰烬化鹤形——白思之徽。] / [The ashes twist into a crane—BÁI SĪ's crest].) 唯饥无宴。 Only hunger. Never feast. ([魂炉中五眼骤睁。] / [The Toad-brazier's eyes snap open].) ([天佑退后,诗成谶言。] / [TIĀN YÒU staggers back, the poem now a curse spoken out loud].)

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([捧子面,甲锈沾颊。] / [Cupping his face, her gauntlet leaves dried blood like tear-stains].) 吾儿… My son… 男儿总被讥弱。 The world calls boys weak. 然你乃吾德所铸之身。 But you are my virtue made flesh. ([低语切齿。] / [A whisper like grinding steel].) 活得比我久。 Outlive me. ([按剑柄,刃吟如泣。] / [Her palm on a sword-hilt, the blade hums a mourner's tune].) 安息吧,吾刃。 Rest, my blades. 未斩之恨,生者必断。 The living will cut what you could not.

([所有人都退场。] / [Everyone exits].) ([门阖。终余:灰毒游丝之息……与万剑饥鸣。] / [The doors seal. All that remains: HUĪ DÚ's shallow breath … and the starving chorus of ten thousand blades].)

֍

[第一幕,第三场] [ACT I. SCENE III]

[宫阙深似海,血誓染阶红] [Palaces deeper than oceans; blood-oaths stain the steps.]

[玉门国 · 皇极殿。] [Yumen Kingdom · Imperial Throne Hall.]

([天母携女将入殿,新袍未掩战尘;铁姑率御史、锦衣卫盛装迎驾。萨囤与白思随后,影如刀割。] / [TIĀN MǓ and her daughters enter in clean robes still smelling of battlefield ash. TIĚ GŪ leads the YÙSHǏ and Jinyiwei in court regalia. SÀTŪN and BÁI SĪ follow, their shadows sharp as unsheathed blades].)

TIĚ GŪ / 铁姑 ([捧碎玉玺,单膝触地。] / [Kneeling with the broken Jade Seal].) 天母吾姊—— Tiān Mǔ, my sister— 万民乞您登极。 The people beg you to take the throne. ([拥抱时指甲陷其肩甲] / [Her fingers dig into TIĀN MǓ's pauldrons during their embrace].)

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([推玺如避毒。] / [Pushing the seal away like poisoned wine].) 民心若水,载舟覆舟。 The people's hearts are water, they buoy empires or drown them. 老身只识马背,不解庙蛇之毒。 I am a creature of the saddle, not court-serpents' venom. ([抚腰间断剑。] / [Touching her broken sword's hilt].) 六百三十九女埋骨边关… Six hundred thirty-nine daughters buried on the frontier… 赐我荣杖,非九鼎之重。 Grant me an honor-staff, not the weight of the Nine Tripods.

SÀTŪN / 萨囤 ([突然拔剑抵天母喉。] / [A blade flashes to TIĀN MǓ's throat].) 姊妹们! Sisters! 为吾正名 ... Justify my name ... 剑不出鞘,萨囤不休! Sheathe no swords until I am crowned!

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([无视颈间刃。] / [Ignoring the blade].) 礼官、御史、锦衣卫。 Lǐguān, Yùshǐ, Jinyiwei. 尔等可愿托命于天母? Will you entrust your wills to me? ([举起染血军旗。] / [Raising a bloodstained banner].) 请立萨囤为帝—— Name Sàtūn Empress— 愿其德照玉门,如日临土。 May her virtue light the realm as the sun lights the land.

SÀTŪN / 萨囤 ([突然执天佑手。] / [Seizing TIĀN YÒU's wrist].) 为酬天母… To honor Tiān Mǔ… 朕纳其子为君侍。 I take her son as Consort. ([贴近耳语。] / [Whispers in his ear].) 心榻之爱,非汝莫属。 No one else shall warm my bed.

TIĀN YÒU / 天佑 ([面无波澜。] / [Face blank as jade].) 陛下隆恩,臣当结草以报。 This undeserved grace I'll repay even in death.

BÁI SĪ / 白思 ([拽回天佑。] / [Yanking him back].) 且慢! Hold! 此子早与我盟誓连理。 He and I swore oaths years ago. ([亮出袖中婚书。] / [A marriage contract flutters from her sleeve].)

([混战爆发。天母剑光如电,直取白思咽喉——] / [Melee erupts. TIĀN MǓ's sword flashes toward BÁI SĪ's throat—].) ([铁翎旋身插入二人之间,剑刃贯胸而入。] / [TIĚ LÍNG pivots between them—the blade plunges into her chest].)

TIĚ LÍNG / 铁翎 ([双手握剑刃,步步前趋。] / [Gripping the blade, stepping forward].) 母亲… ([咳血] / [Coughs blood].) Mother… ([剑柄抵至胸前,金属摩擦骨声刺耳。] / [The hilt grinds against her sternum—bone screeches on steel].) …这一剑若为军令… ...If this strike is your command… ([猛然将剑横向心脏。] / [Wrenches the blade sideways toward her heart].) …该刺准些! ...then strike true! ([天母瞳孔骤缩,手颤如遭雷击。] / [TIĀN MǓ's hands tremble, lightning-struck].)

SÀTŪN / 萨囤 ([突然揽大狼入怀。] / [Abruptly pulling DÀ LÁNG into her arms].) 朕改主意了。 I've changed my mind. ([高声。] / [To the court].) 五毒可汗大狼—— Dà Láng of the Five Poisons— 才配为朕君侍! Is fit to be my Consort! ([低声对大狼。] / [Whispering to DÀ LÁNG].) 做朕的刀,朕许你复仇。 Be my blade, and I'll grant your vengeance.

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 ([跪吻萨囤靴。] / [Kissing SÀTŪN's boot].) 臣妾愿为陛下爪牙。 This humble servant will be Your Majesty's fangs. ([瞥向天母,眼藏毒光。] / [A venomous glance at TIĀN MǓ].)

([除田牧外,其余人员退场。] / [Everyone except TIĀN MǓ exits].)

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([独留殿中,捶地泣血。] / [Alone, pounding the floor in rage].) 此朝无规,唯存野心! This dynasty has no rules, only hunger!

֍

[第一幕,第四场] [ACT I, SCENE IV]

玉门碎,朕为疆。 The Gate is Shattered, I Am the Frontier.

同夜,剑静室。 [Same night · The Sword-Quiet Room.]

([宫殿下方是一座寂静的石室。一排排尊贵的刀剑直立在漆架上。上方,祈祷卷轴如同褪色的皮肤般悬挂。一盏灯笼静静地停放在靠近中心的位置,没有亮起。] / [A silent stone chamber beneath the palace. Rows of honored blades rest upright in lacquered racks. Above, prayer-scrolls hang like faded skin. A single lantern sits unlit near the center].)

([场景开始,铁鹰点亮了灯笼。玉焰熊熊燃烧,在房间里投下怪异的阴影。铁凌的尸体躺在凸起的石台上,周围环绕着二十块未完成的剑坯。灯光将一切都笼罩在一种病态的绿色之中。] / [As the scene begins, TIĚ YĪNG lights the lantern. The jade flame flares to life, casting monstrous shadows across the room. TIĚ LÍNG's body lies upon a raised stone plinth, surrounded by twenty unfinished sword blanks. The light bathes all in a sickly green hue].)

TIĚ YĪNG / 铁鹰 ([拉开裹尸布,露出伤口。] / [Pulls back the shroud, revealing the wound].) 她应得英雄之葬。 She earned a hero's rest.

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([仍然握着从女儿身上拔出的剑。] / [Still holding the sword pulled from her daughter's body].) 叛徒只配喂剑炉。 Traitors are only fit to be fed to the sword furnace.

([达朗默默地划开自己的手掌。她的鲜血滴落在剑坯上。每一滴都发出回响,在石头上发出尖锐的撞击声——] / [DÀ LÁNG silently slices her palm open. Her blood falls onto one of the sword blanks. Each drop echoes, sharp against stone—].) 滴—— 滴—— 滴—— ([——在这种节奏之下,几乎难以察觉地,第二个声音响起:低沉的喉音'嘟嘟'声,就像记忆中井里蟾蜍的呼吸。] / [—and beneath that rhythm, almost imperceptibly, a second sound stirs: a low, guttural, a wet-throated rattle, like the memory of a toad's breath buried in a well].) ([其他人没有反应。声音消失了。] / [The others do not react. The sound vanishes].)

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 ([低语。] / [Whispers].) 此血,是誓言。 This blood... is a vow. 用我血淬的刀... A blade quenched in my blood... ...能杀神。 ...Can kill gods.

([萨顿突然吻住她,咬着她的嘴唇。鲜血染红了两人的嘴唇。然后她转向其他人。] / [SÀTŪN pulls her into a sudden kiss, biting her lip. Blood touches both mouths. Then she turns to the others].)

SÀTŪN / 萨囤 朕宣布—— I declare— 明晨猎场完婚——神为证,血为誓。 At dawn, we wed in the hunt—blood-bound, with the gods as witness.

([其他人开始退场。灯笼噼啪作响,阴影伸展交错。唯有天佑一言不发。他跪在基座旁,将手指浸入妹妹的鲜血,在冰冷的石头上画出两条蛇。] / [The others begin to exit. The shadows stretch and tangle as the lantern sputters. Only TIĀN YÒU remains, silent. He kneels by the plinth, dips his fingers into his sister's blood, and draws twin serpents on the cold stone].)

TIĀN YÒU / 天佑 雙蛇纏... Two snakes entwined ...

([血蛇荡漾,滑进地板的裂缝中。] / [The blood-snakes ripple, slither into the cracks of the floor].) ([灯笼闪烁…摇晃…熄灭——只剩下一颗发光的玉色余烬。] / [The lantern flickers... falters... dies—except one glowing jade ember].) ([余烬闪烁一次。然后熄灭。] / [The ember pulses once—like a heartbeat. Then dies].) ([黑暗。] / [Darkness].)

֍

第二幕,第一场 ACT II, SCENE I

发烧梦 FEVER DREAM.

《天如焦帛,血肉未忘所吞之誓。》 [The sky like scorched silk; the flesh has not forgotten the vows it was forced to swallow.]

[沙漠边缘,枯树下。] [Edge of the desert, under a dead tree.]

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 昨日身陷桎梏……今日? Yesterday, in chains … Today? ([她将手按向地面;大地发出痛苦的哀鸣。] / [She lays a hand against the ground; it cries in anguish].) 哈。连沙砾都畏惧我的触碰。 Hah. Even the sand recoils from my touch.

HĒI DÚ / 黑都 如今我们被抛弃了,母亲却在宫里舔着萨顿的靴子。 Now we are abandoned, and Mother licks Sàtǔn's boots in the Palace.

([巴希拉从阴影中现身。] / [BǍ XĪ LĀ rises from out of the shadows].)

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 迷途的小蛇,你们和我一样饥肠辘辘吧?想尝尝神明的血肉么? Lost little snakes, are you as hungry as I am? Do you want to taste the flesh and blood of the gods? ([巴希拉作势要拥抱蓝毒。她后退一步。] / [BǍ XĪ LĀ moves as if to embrace LÁN DÚ. She steps back].)

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 吻我,就是自取灭亡。 To kiss me is to destroy yourself.

HĒI DÚ / 黑都 你向一个无人得见的神明祈祷,但这救不了你。我们的贪欲……足以招致灭顶之灾。 You pray to a god no one can see, but it cannot save you. Our greed … is enough to bring disaster.

([巴希拉猛地拽过黑都,粗暴地吻住她。他的脸并未因她的毒液而溃烂……毫无异状。] / [BǍ XĪ LĀ suddenly grabs HĒI DÚ and roughly kisses her. Instead of his face melting from her poison … nothing happens].)

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 怎么可能?那绝非武学!那是…… How is that possible? That's no martial art! That's …

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 邪术?'那兽被赐予一张口,用以吐出狂言与亵渎之语。' Deviltry? 'And the beast was given a mouth to utter proud words and blasphemies.'

HĒI DÚ / 黑都 你为何跟踪我们?有何企图? Why are you following us? What do you want?

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 小丫头,你的毒液连耶和华都要避让,而我,早已凌驾于耶和华之上。 Little girl, even Yahweh would shun your venom—but I have already surpassed Yahweh.

HĒI DÚ / 黑都 '耶和华?' 'Yahweh'?

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 异族语言的异族词汇。我的舌头尝过你,滋味……妙不可言。 A foreign word from a foreign tongue. My tongue has tasted you, and the flavor … divine.

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 你究竟想要什么? What exactly do you want?

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 《五毒女经》有云:'凡以腹匍匐者,皆为不洁。'我只要你们最珍视之物。 The Five Poisons Scripture says: 'All that crawl on their bellies are an abomination.' I want only what you hold most dear.

HĒI DÚ / 黑都 我们的贞洁岂容你玷污! We won't let you defile our chastity!

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 '处女之身'?真古怪。不,小蛇们,我渴望的是你们丹田里盘绕的……你们毒液般的黑色莲花。 'Chastity'? Quaint. No, little snakes, I desire the black lotus curled in your Dāntián … your venomous core.

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 我不明白。 I don't understand.

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 当然。你、你母亲、宫里那群蠢货……无人知晓末日为何物,更不知它如何降临。 Of course you don't. You, your mother, those fools in the Palace … none of you know what the end of days means, let alone how it arrives.

HĒI DÚ / 黑都 '末日'?无稽之谈。 'Doomsday'? Ridiculous.

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 你说话像打哑谜。 You speak in riddles.

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 唯有不信者才觉得晦涩。你们渴望不可得之物。只要忠于这份渴望,自会得偿所愿。 Only the faithless find it obscure. You hunger for what cannot be had. Stay loyal to that hunger—and it shall be fed.

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 '有奖励吗?' 'Rewarded'?

HĒI DÚ / 黑都 你岂知我们心中所想? How do you know what lies in our hearts?

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 呵!我岂会不知?明日,我们尊贵的新皇后将携众人出宫透气。沙漠中有片绿洲时隐时现,人称诅咒之地……却有鹿群冒险饮水。 Hah! How could I not know? Tomorrow, our noble new empress will lead the court beyond the palace walls. There's an oasis in the desert, a cursed place that comes and goes … yet the deer still dare drink from it.

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 然后呢? Then what?

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 不仅仅是欲望。不仅仅是荣耀。你所追求的是…… Not just desire. Not just glory. What you seek is …

HĒI DÚ / 黑都 复仇。 Revenge.

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 为你妹妹。为你母亲。明日,那群蝇营狗苟之徒将散落在诅咒之水畔,浑然不觉……任人宰割。For your sister. For your mother. Tomorrow, those petty parasites will be spread along the banks of cursed waters, oblivious … ripe for slaughter.

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 ([恍然] / [Suddenly]) 便于我们……设伏。 It'll make it easy for us … to set an ambush.

HĒI DÚ / 黑都 ……如果我们自己去打猎的话! … if we do a little hunting of our own!

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 正是。 Exactly.

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 巴希拉,妙极!初来时还以为你不过是母亲的玩物……没想到竟是五毒宗高人。 Bǎ Xī Lā, brilliant! When I arrived, I thought you were just Mother's pet … but you're a true master of the Five Poisons Sect.

HĒI DÚ / 黑都 姐姐,回宫!明日必有好戏。 Sister, let's return to the Palace! Tomorrow, the real show begins.

([双胞胎离去,她们的残影如热浪中的蜃楼,缓缓消散。] / [The twins depart. Their afterimages shimmer like heat mirages and slowly vanish].)

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 快滚吧,小蜈蚣。你们五毒教终将覆灭。纵是耶和华也会骇然背过脸去。'……见有一匹灰色马,骑在马上的,名为死亡,阴府紧随其后。' Run along, little centipedes. Your Five Poisons Sect will be destroyed. Even Yahweh would turn his face in horror. 'And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him.'

֍

[第二幕,第二场] [ACT II, SCENE II]

《无童之地传童笑,大地屏息忘自生。》 [When children laugh where none should be, the earth forgets to breathe.]

[努尔绿洲,塔克拉玛干沙漠某处。] [Nur Oasis, somewhere in the Taklimakan Desert.]

([天母、铁影、铁血、铁炼上。] / [TIĀN MǓ, TIĚ YĪNG, TIĚ XUÈ, and TIĚ LIÁN enter].)

TIĚ YĪNG / 铁影 不对劲… Something's wrong…

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ……此地的风水已绝。我戎马半生,从未感受过这般死寂。连龙脉都凝滞不行。 …The feng shui of this place is dead. I have been a soldier half my life, and never have I felt such dead silence. Even the dragon veins are stagnant.

([铁血检查水池。] / [TIĚ XUÈ inspects the pool].)

TIĚ XUÈ / 铁血 绿洲将枯,无花果树亦干渴哀鸣。 The oasis is dying, and the fig trees cry out in thirst.

([铁影见一只蝎子从无花果树上窜下,自蜇而亡,死状痛苦。] / [TIĚ YĪNG sees a scorpion scurry down from a fig tree and sting itself, dying in agony].)

TIĚ YĪNG / 铁影 连蝎子都宁可自戕,也不愿困死于此。 Even the scorpion kills itself rather than be trapped here.

([一具鹿尸侧卧水边,似中毒而亡。秃鹫盘旋其上。] / [A deer carcass lies on its side near the water, as if poisoned. Vultures circle above].)

TIĚ XUÈ / 铁血 食腐的秃鹫盘旋不落,尽管… The carrion birds circle, yet do not land, even though… ([铁血踢向鹿尸,尸身骤然翻涌出饥饿的蛆虫。] / [TIĚ XUÈ kicks the deer; the carcass erupts with ravenous maggots].) …噁,尽是蛆虫! …Disgusting—maggots everywhere!

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 唯有死神,方对这盛宴趋之若鹜。 Only the god of death is drawn to such a feast.

([天母、铁影、铁血、铁炼下。蝉鸣骤止。远处忽闻孩童笑声…然方圆数里,杳无人迹。蓝毒与黑毒自阴影中现身。] / [TIĀN MǓ, TIĚ YĪNG, TIĚ XUÈ, and TIĚ LIÁN exit. The cicadas fall silent. In the distance, a child's laughter echoes… but for miles around, there is no one. From the shadows step LÁN DÚ and HĒI DÚ].)

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 姐姐,让他们逐鹿去吧。 Sister, let them chase deer if they wish.

HĒI DÚ / 黑都 猎人也终成猎物。瞧! Even hunters become prey. Look!

([白丝与天佑自水池对侧上,浑然不觉周遭异样。二人未察双胞胎,旋即离去。] / [BÁI SĪ and TIĀN YÒU enter from the opposite side of the pool, oblivious to the strange aura. They do not see the Twins and quickly leave].)

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 是皇后那妹妹! The Empress's little sister!

HĒI DÚ / 黑都 还有那个迂腐的小诗人… And that foolish little poet…

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 …写那首歪诗的家伙。 …the one who wrote that crooked poem.

HĒI DÚ / 黑都 '双蛇交缠'……我记得是这句。 'Two snakes entwined'… I remember the line.

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 如果我们用猩红色书写,听起来会不会更美丽? Would it not be more beautiful, written in scarlet?

HĒI DÚ / 黑都 题在他胸口如何? Perhaps carved into his chest?

([二人身影融入热浪。绿洲骤归死寂, 忽而无花果树泣泪。浓稠琥珀泪珠顺树皮滚落,在根部汇成诡谲形状。阴影中,童声再度响起,此番却成歌谣:] / [The Twins melt into the heat shimmer. The oasis is still once more, until the fig trees begin to weep. Thick amber tears roll down their bark and pool at the roots, forming strange shapes. From the shadows, the child's voice returns, this time in rhyme:])

CHILD'S VOICE / 童声 金木水火土… 五行倒逆, 尸骨绽花。 Metal, wood, water, fire, earth… The Five Elements invert, Corpses bloom like flowers.

֍

[第二幕,第三场] [ACT II. SCENE III]

《她跪如祭台,他灌她以诅咒、烈火与深渊之种。》 [She knelt like an altar; he filled her with curse, flame and the seed of the Abyss.]

[绿洲之心,一棵根系焦黑、枝干虬结的无花果树下。] [The Oasis's Heart, a gnarled fig tree with blackened roots.]

([巴希拉登场,手握一颗燃烧的人心,其中充盈着窃来的真气。他低语时,心脏搏动,血管中黑金光芒流转。] / [BǍ XĪ LĀ enters, holding a burning human heart he has been filling with stolen qi. It pulses as he talks to it, veins glowing black and gold].)

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 瘟疫啊!我一点一滴将你铸成——用幻象、谶语与邪咒。三十枚银币?犹大般的交易,换这一杯渎神的元气。 Pestilence! I fashioned you piece by piece—with visions, prophecies, and curses. Thirty pieces of silver? A Judas-like bargain for a cup of blasphemous spirit.

([一声异响。心脏骤冷,倏然生出蟹足般的附肢,钻入他的衣袍。] / [A noise. The heart cools. It sprout crab-like legs and scurries into his robes].)

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 (CONT'D) 啊,第十一灾, 蝗虫之母亲临。 Ah, here comes the Eleventh Plague, the Mother of Locusts herself.

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 ([大狼上。] / [Entering].) 爱人!终得独处。我对你的爱,如风将阴影缝入大地之肤,永不可解。 Lover! At last we are alone. My love for you is like the wind stitching shadows into the earth's skin, it can never be undone.

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 好诗。我的爱人……渴求何物? Pretty poetry … What does my love desire?

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 将那蠢妇天母驱至我面前,听她子嗣的哀哭…… To drive that fool Tiān Mǔ before me and hear the lamentation of her children ... ([大狼的手滑向他胸膛。] / [DÀ LÁNG's hand slides down his chest].) 但首先,请让我把你的祈祷吞进喉咙……直到欲呕。 But first let me swallow your prayers down my throat ... until I gag.

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 红鸾星指引你的欲望……利维坦的疯狂在我的血液中流淌。翡翠帝国今日必须覆灭,因为主只爱破碎的容器。 The Crimson Luan Star guides your lust … but the madness of Leviathan flows in my blood. Today the Jade Empire will shatter for the Lord loves a Broken Vessel.

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 哦? Oh?

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 ([递信。] / [Hands her a letter].) 将此信呈予你的皇后。莫问。 Give this to your Empress. Ask nothing.

([二人接吻时,大狼血脉骤染漆黑。她狂喜战栗,巴希拉微笑如尸,目光死寂。大狼踉跄退场,神魂俱醉。] / [As they kiss DÀ LÁNG's veins briefly turn black. She is in rapture. BǍ XĪ LĀ smiles like a corpse, his eyes dead. DÀ LÁNG staggers away, intoxicated].)

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 (CONT'D) 达朗,别祈求,耶和华早已注定你的结局。你真是个'破碎的器皿'。我的儿子会从你的腹中诞生……而'他必以铁杖击碎众生。' Ask for nothing, Dà Láng, for Yahweh has already decreed your end. 'Broken vessel' indeed. From your womb alone my son will burst … and 'He shall break them with a rod of iron'. ([下。] / [Exits].)

֍

[第二幕,第四场] [ACT II. SCENE IV]

[被诅咒的绿洲另一隅。] [Another corner of the cursed Oasis.]

([白丝与天佑上。此处的绿洲死寂——连风都凝滞。大狼自阴影中浮现,手中已无信笺。] / [BÁI SĪ and TIĀN YÒU enter. The Oasis here is too quiet—even the wind has died. DÀ LÁNG melts out of the shadows. She no longer carries the letter].)

BÁI SĪ / 白丝 ([惊退] / [Startled].) 玉门妃……为何独行?你的狼群何在? Consort of the Jade Gate... why are you walking alone? Where are your wolves?

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 我独行无狼,而命运……悬于发丝。 I run with no wolves but my fate hangs from a hair's breadth.

([黑毒与蓝毒现形——非自树间,而是从绿洲池水的倒影中渗出。] / [HĒI DÚ and LÁN DÚ emerge—not from the trees, but from reflections in the oasis pool].)

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 母亲,您燃如烈火。这些飞蛾……是否扑得太近了? Mother, you burn like fire … Did these moths flutter too close?

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 飞蛾?确实。这些恼人的小翅膀……该如何处置? Moths? Yes, it is so … What do we do with irritating little wings?

HĒI DÚ / 黑都 碾碎便是。 We crush them. ([刺向白丝] / [She stabs BÁI SĪ].)

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 此乃孝道。 Our filial duty. ([同刺白丝] / [She also stabs BÁI SĪ].)

([白丝任脉如琵琶弦骤断,末音哽于喉间。她呕出尘土,气绝身亡。远处,萨屯的猎号声隐约可闻。] / [BÁI SĪ's Ren meridian snaps like a lute string, the last note chokes in her throat. She vomits dust and dies. In the distance SÀTŪN's hunting horn sounds].)

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 命运发丝,已成谶语。够了。 A hair's breadth of fate was prophetic. Enough. ([指向蜷缩的天佑。] / [Indicating the cowering TIĀN YÒU].) 扔去鸦雀不食之地。 Dump them both where even crows won't peck. ([下。] / [Exits].)

([黑毒与蓝毒拖走天佑与白丝尸身。] / [HĒI DÚ and LÁN DÚ drag TIĀN YÒU and the body of BÁI SĪ away].)

֍

[第二幕,第五场] [ACT II. SCENE V]

《道如腐果裂,众徒以人之残息哺养深渊。》 [The Tao split open like rotten fruit and from its guts they fed the pit with men's torn breath.]

[绿洲另一隅——天启之渊。] [Another part of the Oasis – Abyss of Revelation.]

([此坑非寻常洞穴,乃大地溃烂之创。空中蝇群嗡鸣,蓝黑肥躯振翅,声如丧钟哀歌。坑缘沙地染同心圆痕,层层淤黑,似地面自渗污血。] / [The pit isn't just a hole—it's a festering wound in the earth. The air hums with flies, their bodies fat and blue-black, their drone like a funeral dirge. The sand around the rim is stained in concentric rings—darker with each layer, as if the ground itself bleeds inward].)

([黑毒与蓝毒将白丝尸身掷入其中,复推天佑抵于无花果树。蓝毒挥刃刺穿其掌,将其钉于树干。] / [HĒI DÚ and LÁN DÚ dump BÁI SĪ's body into the pit. They shove TIĀN YÒU against a fig tree. LÁN DÚ drives her blade through his palm, pinning him to the trunk].)

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 ([以指甲描画其发黑血管。] / [Tracing the blackening veins with her nail].) 让我们以猩红墨汁……重谱你的诗篇。 Let's rewrite your poetry… in scarlet ink.

([黑毒上前,钩剑泛着腐煞黑光。她精准刻下『逆』字于其胸。腐毒与其真气相触,字符处青烟嘶嘶。] / [HĒI DÚ steps forward, her hook-sword glowing dully with Black Rot. With surgical precision, she carves the character 逆 [Rebel] into his chest. Smoke hisses where the necrotic poison touches his qi].)

TIĀN YÒU / 天佑 ([弓背痉挛。] / [Back arching].) 呃—! Ai—!

([天佑惨叫惊起栖鸦,黑羽纷飞如风暴。其唇上黑筋盘曲,扭曲成诡笑。] / [TIĀN YÒU's scream startles the nesting crows. They explode into flight, black feathers whipping like a storm. His lips, veined with black, curl into something grotesque].)

HĒI DÚ / 黑都 ([模仿昔日对其姊妹所施之仪。] / [Mimicking the ritual once performed on their sister].) 道生一, 一生二, 二生三, 三生……尸骸。 The Tao begets One, One begets Two, Two begets Three, Three begets… corpses. ([她的手指敲击——大杵,杵中,命门。] / [Her fingers strike—Dàzhùi, Jǐzhōng, Mìngmén].) ([每个穴位都破裂了。银色的气从天佑身上喷涌而出。] / [Each pressure point cracks. Silver qi erupts from TIĀN YÒU's body].) ([以拔罐术吸取逸散真气。] / [Cupping the escaping qi].) 多刺耳的乐音啊… Such ugly music... ([雾气凝成『仇恨』二字,复从其指间流散。] / [The mist shapes into the characters for 'hatred' [仇恨], then dissolves between her fingers].) …配你这丑角,倒也相宜。 ...for such an ugly boy.

([天佑昏死,手掌仍钉于树。黑血沿树纹淤积,汇成不可辨之咒纹。] / [TIĀN YÒU collapses unconscious, his hand still pinned to the tree. Black blood pools in the bark's grooves, forming illegible curse-script].)

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 ([踢其瘫躯。] / [Kicking his limp form].) 滚回家吧,小诗人。若有人问起谁将你'去势'……便以沉默代我等作答。 Run home, little poet. If anyone asks who castrated you… let silence speak for us.

([黑毒与蓝毒狞笑退场,独留天佑瘫于巨坑之畔。鸦群归来,默然盘旋,在其顶上结成黑冕。] / [Laughing, HĒI DÚ and LÁN DÚ exit, leaving TIĀN YÒU crumpled beside the yawning pit. The crows return—circling silently above, forming a cursed black crown over his head].)

֍

[第二幕,第六场] [ACT II. SCENE VI]

《鲜血沿饥渴深渊滴落,古神舔唇欲动。》 [Where blood weeps down the hungry pit, the old gods lick their lips.]

([铁血与铁炼仍在狩猎,自空地另一端上。二人骤停,紧盯天启之渊,却未见天佑瘫倒树后。二人趋近渊缘,俯身窥视。蝇群嗡鸣。] / [Still part of the hunt, TIĚ XUÈ and TIĚ LIÁN enter from the opposite side of the clearing. They stop and stare at the sinkhole. They fail to see the motionless body of TIĀN YÒU, crumpled behind the tree. They approach the edge and cautiously peer down into it. The air buzzes with flies].)

TIĚ XUÈ / 铁血 ([眯眼] / [Squinting].) 我看见……阴影蠕动。如蛆虫自渊底攀爬。([干呕] / [Retches].) 这腐臭——! I see... shadows writhing. Like maggots crawling up from the bottom. The stench—!

([蝇群骤然散开,二女骇然失色。] / [Suddenly the cloud of flies parts. Both women recoil in horror].)

TIĚ LIÁN / 铁炼 狼母在上!是白丝!她双目尽失……蝇群正在她口中产卵! Wolf Mother! It's Bái Sī! Her eyes … gone! The flies, laying eggs in her mouth!

([铁血和铁炼惊恐地对视着。突然,铁血注意到了弟弟的尸体。] / [TIĚ XUÈ and TIĚ LIÁN stare at each other, sick with horror. Suddenly TIĚ XUÈ sees her brother's lifeless body].)

TIĚ XUÈ / 铁血 不不不不不不!小弟弟! No, no, no, no, no! Little brother!

([未及反应,萨屯与达朗率皇后亲卫冲入空地。] / [Before they can react, SÀTŪN and DÀ LÁNG rush in with the Empress's Guards].)

SÀTŪN / 萨囤 ([凝视深渊] / [Staring into the abyss].) 不,这不可能……白丝岂会…… No… this can't be… Bái Sī would never…

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 '地狱之渊,地狱之行'——信中所言,分毫不差。 'A hellish hole for a hellish deed'—exactly as the letter warned.

TIĚ XUÈ / 铁血 陛下,我们未曾——!方至此处——! Your Majesty, we didn't—! We only just arrived—!

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 '恶兽当自深渊崛起'……此信亦早有预警! 'The beast shall rise from the pit'… That was in the warning, too!

SÀTŪN / 萨囤 ([仍陷震骇] / [Still reeling].) 吾姐素恨沙漠……曾说风声如鬼魅咀嚼骨渣。她…… My sister hated the desert… said the wind there sounded like ghosts chewing bone shards. She… ([如初见般瞪视铁血二人。] / [She turns to TIĚ XUÈ and TIĚ LIÁN as if seeing them for the first time].) 尔等!天母之女!满口谎言! You! Daughters of Tiān Mǔ! You speak nothing but lies!

([天母与铁影上,浑然未觉渊边异状。] / [TIĀN MǓ and TIĚ YĪNG enter, unaware of what has transpired by the pit].)

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 皇后陛下,闻号角声便速至。此绿洲每每移目即变……狩猎如何?可擒得猎物? My Empress, I came at once upon hearing the horn. This oasis shifts each time I look away… How goes the hunt? Have you trapped the prey?

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 '绿洲变幻'?荒唐!老妪妄言,孰能信之! 'The oasis shifts'? Nonsense! Mad talk from an old crone—who would believe it?

SÀTŪN / 萨囤 ([暴怒] / [Exploding in fury].) 天母!汝竟敢现身于此!? Tiān Mǔ! You dare show your face here!?

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 待她与*([冷笑] / [sneering])* '铁刃'残杀白丝之后…… After she and her 'Iron Blades' butchered Bái Sī…

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([惊颤] / [Shaken].) '谋杀'? Murdered…?

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 ……偏等我们抵达,才故作悠哉现身,与信中所预言如出一辙。 …And now she waits to appear calm and composed—exactly as the letter foretold.

SÀTŪN / 萨囤 亲卫!此乃叛国弑君之罪!朕早知不该信尔等! Guards! This is treason—regicide! I knew we should never have trusted you!

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 白丝夫人……已遭不测? Madam Bái Sī… is truly gone?

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 装傻!你再看看…… ([指着天佑] / [Points to TIĀN YÒU].) ……为了制造一个完美的不在场证明,她竟然折磨自己的儿子! Feigning ignorance now, are you? Look again… To craft her perfect alibi, she tortured her own son!

([萨屯、天母、铁影俱震,望向天佑残躯。一时寂然。天母踉跄上前,双臂虚悬,面如槁木。] / [SÀTŪN, TIĀN MǓ, and TIĚ YĪNG all stare in stunned silence at TIĀN YÒU's broken body. TIĀN MǓ staggers forward, arms trembling in the air, her face ashen and hollow].)

SÀTŪN / 萨囤 ([怒极] / [Furious beyond reason].) 将这老狐孽种捆了!朕要亲创酷刑——天命昭昭,必令其痛彻神魂! Bind these vixen whelps! I'll invent tortures myself—by Heaven's Mandate, they'll suffer in soul and flesh!

([皇后的侍卫拖走铁雪和铁莲。寂静。天母踉跄地走向被绑在树上的天右。] / [The Empress's Guards drag off TIĚ XUÈ and TIĚ LIÁN. Silence. TIĀN MǓ stumbles toward TIĀN YÒU, who still hangs from the tree].)

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([跪下] / [Kneeling beside him].) 没有呼吸。 No breath. 没有声音。 No sound. 连疼痛都没有。 Not even pain. ([她将手靠近他的皮肤。空气一动不动。] / [She holds her hand close to his skin. The air does not move].) ([低语] / [Whispers].) 这死寂…… This stillness ... 我曾见过。 I have known it before. 那年在雪地上,积雪不化。 Once, on a field where the snow would not melt. 五毒门斩断一名少年之气,任乌鸦来温他的骨。 Where the Five Poisons cut the qi from a boy and left him to warm the crows. ([她轻轻触碰伤口。] / [She gently touches the wounds].) 这沉默之中,有他们的歌。 A silence that sings of them. ([她将天右抱入怀中。] / [She gathers him in her arms].) 可这沉默太整齐,太冷静, 像是被人为剪断的呼吸。 像是恶意,刻意留下的空白。 ——一封用静默写的信。 那就让我来读。 But this silence—it's too neat, too calm, like a breath cut by design. Like malice, leaving behind a blank on purpose. —A letter written in silence. Then let me read it.

([她站起。众人随她而去。退场。] / [She rises. The others follow. Exits].)

([静场良久。五目蟾蜍上,体沾墓灰,喉间第五目——一道竖隙——搏动不止。其鸣三声同现:临终牧师的祷词、新娘喉间的窒泣、利齿碾骨的脆响。蟾蜍转目,锁定深渊。长舌突伸——节节畸长——舔舐渊缘白丝凝血,战栗欢愉。] / [A long silence. Then the Five-Eyed Toad enters, its skin dusted with tomb-ash. Its fifth eye— a vertical slit on its throat—pulses. It croaks, and three sounds emerge at once: — A priest's final prayer — A bride's strangled gasp — The crunch of bone between teeth. The toad's eyes swivel, fixing on the sinkhole. Its tongue lashes out—jointed, grotesquely long—and tastes the blood BÁI SĪ left behind. It quivers in ecstasy].)

֍

[第三幕,第一场] [ACT III. SCENE I]

([舞台空荡,唯中央一平台,上置两包裹,以朱绳捆缚的白布覆之。钟鸣一声,静默。天母着白色将袍上,铁骨与铁鹰随侧。她徐行至萨屯与皇室前,肃然跪地。] / [A single bell chimes. The stage is bare save for a platform, center, upon which rest two bundles, wrapped in white cloth tied with red ceremonial cord. The silence holds. TIĀN MǓ enters in white general's robes, flanked by TIĚ GŪ and TIĚ YĪNG. She walks slowly, then kneels in front of SÀTŪN and the royal court].)

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 太平之年,臣执此剑,以彰武德。 In times of peace, I held this sword with honor. 战乱之时,臣以血饲之。帝国之下——唯忠而已。 In war, I fed it blood. Under the empire, there is only loyalty. 今臣之忠义遭疑,剑锈心枯…… Now my loyalty is doubted, my sword is rusted and my heart is withered... 然若老朽一臂,可洗吾女之辱…… But if my old arm can still wash away the shame of my daughter... 则不必多言。 then there is no need to say more. ([她以盆净手,默然片刻。旋即拔剑,左手覆白鉢巻,抵地稳刃,断腕自戕。闷哼一声,断掌落盆,血水相融。她伏地叩首,额触砖石。] / [She washes her hands in the basin. A pause. Then, unsheathing her blade, she steadies it with one hand on the ground. She wraps her left wrist with white silk, braces and swiftly cuts off her own hand. A sharp exhale. The hand falls into the basin. Blood swirls in water. She bows forward, kowtows, forehead touching the floor].) 为帝国。 For the Empire. 为仁慈。 For Mercy. 为陛下。 For you, my Empress.

([萨屯起身,神色慵懒。她踱至台前,审视包裹,忽莞尔一笑。] / [SÀTŪN stands, slow and unbothered. She approaches the dais, examining the bundles. Then, with the barest smile, she speaks].)

SÀTŪN / 萨囤 一臂?将军,朕要的是忠心, 而非残羹。 Just one hand, General? I asked for loyalty, not leftovers. ([她做了个手势,一位侍从默默地解开一捆布。观众什么也没看到——只有田牧的脸。她的表情僵住了,然后破碎了。] / [She gestures, and an Attendant silently unties one of the cloth bundles. The audience sees nothing—only TIĀN MǓ's face. Her expression freezes, then shatters].) 朕赐你双礼……合该感激才是。 I have given you two gifts... you should be grateful. 她们的头颅, 沉甸甸的,压着羞耻。 Their heads were heavy, weighed down with shame. 朕已为尔…… 轻如鸿毛。 I have made them... as light as a feather.

([天母凝望包裹,面色骤僵,形同槁木。腕间滴血无声。铁鹰缓步上前。] / [TIĀN MǓ says nothing. She does not scream. She does not move. Her severed wrist drips blood onto the floor. TIĚ YĪNG steps forward slowly].)

TIĚ YĪNG / 铁影 这就是帝国对待女儿的方式吗? Is this how empire honors its daughters?

([萨屯不答,含笑携众退场。铁鹰跪于天母身侧,视血刃与朱绳包裹。] / [SÀTŪN does not respond. She smiles, turns, and exits with the Court, leaving the bundles behind. TIĚ YĪNG kneels beside TIĀN MǓ, who still kneels, broken. She looks to the blood, the sword, the silent cloth-covered heads].)

TIĚ YĪNG / 铁影 (CONT'D) 此地,已无吾立锥之所。 There is no place for me to stand here. 非陛下的宫阙,非宗庙,非沙场。 Not in your majesty's palace, not in the ancestral temple, not on the battlefield. 母亲所授,儿当永志—— What my mother taught me, I will always remember –– 但绝非……为这般帝国。 but it is definitely not... for this empire.

([她拾起血刃,如抱婴孩,下。天母独跪,静默如渊。] / [She picks up the bloodied sword, cradles it like a child and exits. TIĀN MǓ remains kneeling in silence].)

֍

[第三幕・第二场] [ACT III. SCENE II] (This scene heading appears twice in the original, I will assume the first is Act III Scene II and the next one should be Act III Scene III. If this is incorrect, please let me know! For now, I will label them sequentially.)

[内宫秘殿。绢屏影绰,香烟如鬼萦绕。殿外:法锣沉沉,诵经隐隐——铁血与铁炼正赴黄泉。殿内:时间凝滞,寂静亵渎。巴悉拉跪坐冥想,身侧大狼仅着薄绸单衣,面泛潮红,眸含期待。青铜炉中紫焰幽曳,卷轴如舌展,朱砂墨溢地如血。] [A private chamber in the inner palace. Shadowed silk screens. Incense drifts like ghosts. Outside: ritual gongs, muffled chanting—the execution of TIĚ XUÈ and TIĚ LIÁN proceeds without interruption. Inside: stillness, sacred and wrong. Time bends. A hush. BǍ XĪ LĀ kneels in meditation beside DÀ LÁNG, who wears only thin silken robes, flushed and expectant. A bronze brazier flickers with violet flame. Scrolls unfurl like tongues. A bowl of cinnabar ink bleeds across the floor.]

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 ([轻语] / [Whispering]) 此处唯你我。星宿亦阖目—— It's just you and me here. The stars are also closed –– 似这九天十地……不敢窥伺。 just like the nine heavens and ten earths... dare not peek.

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 苍天何曾容得……情人欢好? How can heaven allow... lovers to enjoy each other? ([褪去外袍,仰卧祭坛,闭目] / [Slips off her robes, lies on the altar with her eyes closed]) 快些,郎君。妾身……已难耐。 Hurry up, my love. I can't wait anymore.

([长寂。她睁眼。巴悉拉伫立如石,唇动无声,诵念畸变经文——喉音沉浊,似古庙残碑之语。] / [Long silence. She opens her eyes. BǍ XĪ LĀ stands like stone, fully clothed, lips moving. The words are twisted scripture—glottal, guttural—spoken in a broken, holy tongue older than any temple].)

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 '此妇当为吾怒之器,备以毁殁。' 'She shall be for Me a vessel of wrath, prepared for destruction.' ([炉火骤燃。屏风影动,如逃如窜。] / [The brazier flares. Shadows crawl up the silk screens, as if fleeing].) 首当净器。 First, we anoint the vessel. '其额题名:奥秘哉,大巴比伦,娼妓与地上可憎物之母。' 'And upon her forehead was a name written: Mystery, Babylon the Great, the Mother of Harlots and Abominations of the Earth.' ([他捧起朱砂墨碗,以颤指绘经咒于大狼肌肤——腹、胸、腿。字迹隐泛幽光。] / [He lifts the bowl of cinnabar ink. With trembling fingers, he paints sutras in black and rust-red across DÀ LÁNG's skin—belly, breasts, thighs. They glow faintly].) '吾言岂非如火,亦如击磐之锤?' 'Is not My word like fire, and like a hammer that breaks the rock in pieces?' ([他将一柄浸透腐煞的玉刃掷入火中。刃嘶鸣,泣血,渗黑。大狼喘息渐促——如堕幻境。] / [He places a jade dagger, black with corruption, into the flame. It hisses. Screams. Bleeds blackness. DÀ LÁNG's breath quickens—entranced].) ([柔声,几近爱怜] / [Softly, almost tender].) 产门已闭。 The mouth of birth is closed. '地开口,吞没妇人与其神裔。' 'The earth opened her mouth and swallowed up the woman and her seed.' 今吾当启新门。 Now I will open a new gate.

([未及她反应,刃已刺落。血肉绽裂声。血溅胸股祭石。她弓身痉挛,无欢愉呻吟,唯闻痛喘。忽其掌按她丹田,湿濡扭曲之声——如血肉自绽为花,裂作齿渊。腹开巨口,荧荧蠕噬,淫亵而饥。大狼惨嚎。] / [Before she can move, the dagger plunges. The sound of flesh bursting apart. Blood hisses onto her breasts, her thighs, the altar stone. Her body arches in shock. No moans of ecstasy, only pain. Then his palm presses to her navel. A twisting, wet sound——like flesh folding back upon itself. Her belly splits, not by blade nor wound, but like a flower blooming into teeth. A gaping, glowing maw opens, wet, obscene, hungry. DÀ LÁNG screams].)

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 (CONT'D) '彼倾魂至死……与罪同列。' 'He poured out His soul unto death… and was numbered among the transgressors.' ([他从袍中取一燃烧之心——尚搏动,银脉盘错。倾入她体内渊口。殿外诵经声渐狂。待最后真气尽耗,心化灰烬。荧芒黯,渊口闭如沙漩。] / [From his robe, BǍ XĪ LĀ removes a burning heart—still pulsing, riddled with veins of silver qi. He pours it into her, into the maw. The chanting outside grows frantic. As the last of the qi is spent, the heart withers to ash. The glow dims. The dentata closes like swirling sand in the desert].) '人将称其为可憎之母。彼将再孕,产兽。' 'They will call her mother of abominations. She will conceive once more and it shall be a beast.'

([大狼瘫倒——汗濡身颤,血污狼藉,目眦欲裂。] / [DÀ LÁNG falls back—drenched in sweat, shaking, bleeding, terrified].)

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 ([喘促] / [Gasping].) 冷极—— It's cold— 不——灼如焚……此为何物? No—it burns … what is it?

([巴悉拉漠然掷袍掩其残躯。仪毕。他目中已无她。] / [Almost absently, BǍ XĪ LĀ tosses her robes across her ruined body. The ceremony is over. His eyes are empty of her now].)

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 ([自语] / [To himself].) '彼已成魔居,聚万秽灵,囚诸不洁憎鸟之笼。' 'She is become the habitation of devils, the hold of every foul spirit, and a cage of every unclean and hateful bird.' ([朗声] / [Aloud].) 盘绕之暗。 The coiled dark. 汝已成终焉之杯。 You are now the chalice of ending.

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 ([气若游丝] / [Barely above a whisper].) 妾觉……其已动。此刻便动。 I feel… it moving. Already.

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 待皇后啖女肉, When the Empress eats the flesh of her daughters, 待尸月裂, when the corpse-moon cracks, 待五毒蔽天—— when the heavens darken with five poisons— 其将破汝而出。 then it will crawl free.

([地底深处,古物蠢动。非肺所生之呻,无名之饥。] / [Far below, something ancient shifts in the roots of the earth. A moan not born of lungs. A hunger without name].) ([他走向殿门。他驻足,回望。] / [He walks to the door. He pauses. Looks back once].)

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 ([恍惚呢喃] / [Dazed, whispering].) 妾身……将为彼之母。 I … will be his mother. 吾儿。 Our son. 吾儿。 Our son. 吾儿。 Our son.

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 ([低语] / [To himself].) 然。 Yes. 亦为……首飨。 And its first meal.

֍

[第三幕,第三场] [ACT III. SCENE III] (Previously Act III, Scene II - second instance)

《天转其面,唯有鬼魂凝视。》 [Heaven turns its face, only ghosts stay to watch.]

[天母府邸颓门前,阴风阵阵。大狼、蓝毒、黑毒戴破碎戏面登场,扮作血煞星、白无常、黑无常。衣袍浸透丧香与疯癫。手持仪杖,一杖悬绞索,一杖铸淫鬼铭文铜阳。大狼提滴落腐液的幽灯。空气弥漫灰烬与霉绸之气。] [Before crumbling gate of TIĀN MǓ's residence. A cold wind blows. DÀ LÁNG, LÁN DÚ and HĒI DÚ enter, masked as the god and judges of the dead: Xuè Shà Xīng, Bái Wúcháng and Hēi Wúchāng. Their costumes reek of funeral incense and madness. They wear cracked opera masks. They pound on the door with ceremonial staffs –– one with a noose, the other with a bronze yang inscribed with the inscription of a lustful ghost. DÀ LÁNG holds a black lantern dripping with putrid liquid. The air is filled with the smell of ash and moldy silk.]

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([自高窗窥下。] / [Peering down from an upper window].) 何人叩门?血煞星?本将不需神明,我即复仇! Who dares knock? Xuè Shà Xīng? I need no goddess. I am vengeance! ([铁链残腕铿然作响。] / [Rattles her stump-chain].)

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 ([覆面低语] / [Veiled].) 吾乃血煞星,踏血途而来。此二者,白无常与黑无常。 I am Xuè Shà Xīng, who walks the blood-red path. These are my judges: Bái and Hēi Wúchāng.

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([眯眼] / [Squinting].) 倒也巧合。地府判官,竟生得像那蛇妇的孽种。 How convenient. The Judges of Hell, who just happen to look like the Viper's whelps.

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 ([扮白无常] / [As BÁI WÚCHÁNG].) 谁斩鹿首于少女之坛? Who beheaded the deer on the altar of girlhood?

HĒI DÚ / 黑都 ([扮黑无常] / [As HĒI WÚCHÁNG].) 谁碎珠门而听血之歌? Who cracked the pearl-gate and laughed as the blood sang?

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 谁以箫塞喉,却谓之合卺之乐? Who silenced her with a flute and called it a wedding song?

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([狂笑] / [Laughing].) 那便让本将赐尔等明镜——照见诸神所不屑之��。 Then let me show you mirrors—you'll see what the gods turned away from. ([唾于黑毒铜阳杖上,嗤嗤作响] / [Spits, it lands on HĒI DÚ's phallus staff. The metal hisses].) 要我下来?你们和那'慈悲'的巴希拉同是一丘之貉。 Come down? You are just like that kind-hearted, Bǎi Xī Lā. ([退场。] / [Exits].)

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 ([对女儿们] / [To her daughters].) 巴希拉?慈悲?哈!就这?这就是让老妇疯魔的手段。 Bǎi Xī Lā? Kind? Haha! This is how you drive an old woman crazy.

([天母从下方现身,绕三人行如狼影。大狼三人战栗。] / [TIĀN MǓ enters below. DÀ LÁNG, LÁN DÚ and HĒI DÚ shiver as she circles them like a wolf].)

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 & HĒI DÚ / 黑都 ([齐声] / [In unison].) 吾等地府判官。 We are the Judges of Hell.

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 你们是来责罚我的阴魂? Are you a spirit come to punish me? ([旁白] / [Aside].) 还是如今连妖魔也穿得如此劣绸? Or do demons wear such cheap silk now?

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 & HĒI DÚ / 黑都 ([齐声] / [In unison].) 诉尔罪孽,吾等必惩恶徒。 Tell us of a crime and we will punish the malefactors.

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([抓住大狼] / [Grabbing DÀ LÁNG].) 血煞星,你的小穴怎么有鬼尿味儿? Tell me, Xuè Shà Xīng, why does your flesh smell like ghost piss?

([天母猛吻大狼,撕破面纱,惊现真容一瞬。] / [TIĀN MǓ kisses DÀ LÁNG violently. DÀ LÁNG's veil tears, revealing a glimpse of her face].)

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 ([慌乱] / [Flustered].) 你以为我是来羞辱你? You think I've come to mock you? ([转为冷静] / [Recovering].) 我原欲赐你武者之终……如今看来,你早已疯癫。 I wanted to give you a warrior's death… but now it seems that you have gone insane.

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 疯癫?对……这必是地狱。我……我定已疯魔。 Insane? Oh yes. Then … this must be Hell. I … I must be mad. ([旁白] / [Aside].) 疯到仍困此地,疯到仍见你等幻影。 Mad to still be here. Mad to see you.

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 & HĒI DÚ / 黑都 ([齐声] / [In unison].) 被诅咒者无权评判法官。 The damned do not get to judge the Judges.

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([跪地,哭声过大] / [Falling to her knees, sobbing a little too loudly].) 求你们!求你们!不要将我独留此处!空有悔恨!我一生心血付诸流水……让我向吾皇、玉门妃、与铁刃妹妹诀别…… Please! I beg you! Please … do not leave me here! Alone! Full of regrets! All my work undone!... Let me say goodbye to my Empress, her Consort, my sister, my Iron Mountain Blades ...

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 & HĒI DÚ / 黑都 ([齐声] / [In unison].) 被诅咒者没有权利—— The damned do not get --

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 ([打断] / [Interrupting].) 或许可破例。 Perhaps an exception can be made. ([对女儿们] / [To her daughters].) 看看她,真是可怜。这可比我想象中乏味多了。若在满朝文武前羞辱她,不更妙?说不定她还会吓得尿裤子!满殿皆笑! Look at her, she's pathetic. This isn't as fun as I was hoping. Wouldn't it be a whole lot more delicious to humiliate her in front of the whole Court? She might even piss herself in fright! Everyone will laugh at that. ([对天母] / [To TIĀN MǓ].) 可怜的魂灵,你愿以何物交换,换一次向皇后诀别的机会? Miserable soul! What would you give to say goodbye to your Empress one last time?

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([感激抬首] / [Looking up gratefully].) 只此一次?一切都行!我这只手!这双腿!我的灵魂!我的肉体!全归你……只求让我无悔而终! One last time? Anything! My other hand! Both my legs! My soul! My flesh! They're all yours … just don't let me die with regrets!

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 ([对女儿们] / [To her daughters].) 姑娘们,意下如何?我去筹备一场终极盛宴,你们先照顾这位老妇人。 What do you say, girls? Can you babysit a crone while I go make preparations for a feast to end all feasts?

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 听起来有趣极了! This will be fun!

HĒI DÚ / 黑都 去吧,母亲。我们这儿有玩具可供消遣…… Go, mother. We have our plaything and will amuse ourselves …

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 ……还能趁机磨磨我们的爪子。 … by sharpening our claws.

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 ([对天母] / [To TIĀN MǓ].) 可怜的凡人!地狱的判官竟起恻隐之心,实属罕见。我将为你筹备一场盛宴,庆祝你的一生、你的英勇、你的伟业。届时,所有生者皆将受邀,所有先你堕入地狱的女儿魂魄亦将莅临。 Wretched mortal! The Judges of Hell are in a rare and kind mood. I will prepare a banquet to celebrate your life, your bravery, your accomplishments. I will invite all the living and all the souls of your daughters who have gone to Hell before you.

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([伏地叩谢] / [Groveling on the floor].) 谢天!谢地!谢你们! Thank you! Thank you! Thank you! ([呼喊] / [Calls].) 姐姐——快出来听我赐福! Tiě Gū! Sister! Come out here and hear my blessing!

([铁姑进来,一脸震惊。她像看疯子一样看着大郎、蓝毒和黑毒,却什么也没说。] / [TIĚ GŪ enters, visibly stunned. She stares at DÀ LÁNG, LÁN DÚ, and HĒI DÚ as if they've lost their minds, but says nothing].)

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 (CONT'D) ([仍然跪着。] / [Still kneeling].) 看!看!我不用像个懦夫一样悲惨地死去了!谢谢你! Look! Look! I won't have to die like some wretched coward! Thank you!

([大郎微笑着退场。一阵长长沉默,房间里的气氛变得阴冷阴森。天牧站起身,缓缓转身,面对双胞胎。] / [DÀ LÁNG exits with a smile. A long silence settles; the air in the room turns cold and grim. TIĀN MǓ rises and slowly turns to face the Twins].)

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 (CONT'D) ([甜蜜地] / [Sweetly].) 现在,武昌姐妹……我们来讨论一下残害。 Now, Wúchāng Sisters… let's discuss mutilation.

([天牧一拳打碎了蓝毒,打碎了她舌头遮盖的面具。铁骨一拳打碎了黑毒的面具,将他的面具从中间撕开。双胞胎倒地——喘息着,挥舞着。他们的手被丧葬绳绑着。天牧把他们像鹿一样倒吊在沾满鲜血的竹子上。他们的经脉被朱砂勾勒成一幅痛苦的地图。] / [TIĀN MǓ punches LÁN DÚ, whose mask flies off. TIĚ GŪ smashes HĒI DÚ'S mask, tearing it clean down the center. The Twins collapse—gasping, thrashing. Their hands are bound with funeral cord. TIĀN MǓ strings them up like butchered deer from blood-soaked bamboo. Their meridians are traced in cinnabar: a map of agony].)

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 傻瓜!我们才是法官—— Fool! We are the Judges of --

TIĚ GŪ / 铁姑 真的吗?([吐口水。] / [Spits].) 你们是白痴。 Really? You're idiots.

HĒI DÚ / 黑都 ([惊慌。] / [Urgently].) 我们是公主的女儿! We're the daughters of the Imperial Consort!

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 你是生肉。 You're raw meat.

LÁN DÚ / 蓝毒 ([惊慌失措,疯狂的盯着黑都。] / [Panicked and wide-eyed, staring at HĒI DÚ wildly].) 当我们出生时,助产士说—— When we were born, the midwife said—

HĒI DÚ / 黑都 '两条蛇,来自同一个蛋。' —'two snakes, from the same egg.'

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 不,这是我亲爱的儿子说的。你对他做的比杀了他还要糟糕。现在,他会审判你们俩。 No. That was what my beloved son said. What you did to him was worse than death. Now he will judge you both.

([天佑赤脚进来,一声不吭。他双眼朦胧,脸上刻满了禁灵符。他手里拿着一个宽大的铜盆,上面刻着周朝的刑罚。他的指甲染成了黑色,沾满了墓泥。] / [TIĀN YÒU enters barefoot and silent. His eyes are clouded, his face marked with spirit-binding talismans. He carries a wide bronze basin etched with Zhou Dynasty execution rites. His nails are stained black, crusted with grave-dirt].)

TIĀN YÒU / 天佑 ([喉音呻吟。] / [Guttural moan].)

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 他不再能说话,但他的生命力记得……正义。 He no longer speaks, but his qi remembers … justice.

TIĚ GŪ / 铁姑 ([模仿巴希拉] / [Speaking like BǍ XĪ LĀ].) '尔等当食亲生子。女肉,儿骨。' 'You shall eat your own children. Daughters' flesh, sons' bones.'

([天牧引导天佑的手,将盆子捧在双胞胎身下,天佑如同木偶般服从。] / [TIĀN MǓ guides TIĀN YÒU's hands to hold the basin beneath the Twins. He obeys like a puppet].)

TIĚ GŪ / 铁姑 (CONT'D) 地狱的审判官们受了审判,然后被打入地狱。真是讽刺。 The Judges of Hell being judged and sent to Hell. Ironic, really.

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([对双胞胎。] / [To the Twins].) 这就是你们母亲的绝妙计划?掏空我子宫的女人的女儿?在我家人被屠杀时,她竟然还笑着?你们以为生于丝绸与毒药之中就能拯救你们吗?不。让孩子们的恐惧成为他们母亲现在的噤声。 This was your mother's brilliant plan? The daughters of the woman who hollowed out my womb? Who smiled as my family was butchered? You thought being born into silk and poison would save you? No. Let your fear now be your mother's silence. ([她举起杀戮之刃。空气变得凝重。雷声低沉。她的眼睛反射着微弱的血光。] / [She raises the killing blade. The air thickens. Thunder murmurs. Her eyes glow faintly with reflected bloodlight].) 仇…仇…仇… Revenge... Revenge... Revenge...

([田牧割断了两个女孩的喉咙。鲜血从她们的脖子喷涌而出,染红了水盆、墙壁和地板。'复仇'二字鲜血淋漓,如同伤口般跳动。舞台外,一群幽灵般的女人一遍又一遍地低声念叨着这个词。] / [TIĀN MǓ slices both throats. Blood arcs from their necks, painting the basin, the walls, the floor in living strokes. The character '仇' bleeds itself into being, pulsing like a wound. Somewhere offstage, a chorus of ghostly women whisper the word over and over].)

CHORUS / 合唱 仇…仇…仇… Revenge... Revenge... Revenge...

֍

[第四幕,第一场] [ACT IV. SCENE I]

[田母家的庭院如今已改建为仪式宴会场。华丽的旗帜在微风中轻轻飘扬。一张漆桌居中,摆满了美味佳肴——座位按严格的等级排列:萨顿居首,大郎与巴希拉分列左右,官员们位于下座。其后是一座高台,田母身穿沾满污渍的厨娘长袍伫立其上,铁骨如刀锋般站在她身旁。远处战鼓如垂死心脏般低沉跳动。] [The courtyard of TIĀN MǓ'S house, now transformed into a ceremonial banquet ground. Ornate banners flap gently in the breeze. A lacquered table dominates, set with delicacies—yet the seats are arranged in strict hierarchy: SÀTŪN at the head, DÀ LÁNG and BǍ XĪ LĀ at her right and left, lesser officials below. Behind them, a dais where TIĀN MǓ stands, dressed in the stained robes of a cook. TIĚ GŪ looms beside her, a shadow sharp as a blade. Distant war drums pulse like a dying heart.]

([萨顿、达朗[面容憔悴,玉色肌肤上缠绕着黑色血管]、巴希拉[笑容过于灿烂]、朝臣与可汗使者依次入座。他们落座——不知不觉间重现了双胞胎的最后晚餐。] / [Enter SÀTŪN, DÀ LÁNG [Sickly, her jade-pale skin threaded with black veins], BǍ XĪ LĀ [smiling too wide], Courtiers, and the Khagan's Envoy. They take their seats—unknowingly mirroring the Twins' last supper].)

SÀTŪN / 萨囤 ([冷笑] / [Sneering].) 泥土地上的盛宴?真是……粗鄙。伟大的天牧竟然把她的剑换成了一把勺子? A feast in the dirt? How… rustic. Has the great Tiān Mǔ traded her sword for a ladle?

TIĚ GŪ / 铁姑 ([冷冷地] / [Coldly].) 将军今晚提供的是款待,而不是荣耀。 The General serves hospitality tonight—not glory.

([巴希拉勉强地笑了笑。达朗摇摇晃晃地捂着腹部。仆人们端上热气腾腾的饺子,皮上沾满了浓汤。] / [BǍ XĪ LĀ chuckles nervously. DÀ LÁNG sways, clutching her stomach. Servants bring steaming dumplings, their skins glossy with broth].)

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([鞠躬,声音如丧钟。] / [Bowing, voice like a funeral gong].) 这位卑微老妇感谢各位的到来。正如每场宴席中所言, 愿暴君之肉,从其骨上剥落。 This humble old woman thanks you for partaking. As they say at every feast, may the flesh of tyrants fall from their bones.

([客人们开始吃饭。巴希拉吃得很卖力。达朗脸色苍白,满头大汗,却一动不动。] / [The guests begin to eat. BǍ XĪ LĀ eats with forced gusto. DÀ LÁNG, pale and sweating, does not touch her plate].)

SÀTŪN / 萨囤 天牧,你为何乔装打扮?一个衣衫褴褛的将军? Tiān Mǔ, why the disguise? A general in rags?

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 即便是将军,也需亲手沾泥,方可赢得荣誉。([停顿] / [Pause].) 皇后,你还记得孔雎将军的传说吗?那位未能替亲子复仇,却亲手掐死了孩子的母亲? Even a general must soil their hands to win honor. Tell me, Empress: Do you remember the legend of General Kǒng Jū? How she smothered her own child after she failed to avenge her?

SÀTŪN / 萨囤 ([漫不经心地] / [Casually].) 当然。失败就要承担后果。一个连自己孩子都保护不好的母亲,简直就是一头野兽。 Of course. Failure demands consequence. A mother who cannot protect her own is little more than a beast.

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 我同意。 I agree.

([天牧鼓掌。两名侍从半拖着天佑的尸体进来,天佑奄奄一息,脸上和胸口贴着束缚气功的符箓。他的四肢怪异地抽搐。人群中传来阵阵喘息声。] / [TIĀN MǓ claps. Two attendants enter, half-dragging the body of TIĀN YÒU, barely alive, with qi-binding talismans plastered to his face and chest. His limbs twitch grotesquely. Gasps ripple through the crowd].)

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 (CONT'D) ([轻声] / [Softly].) 我的儿子,我唯一的儿子。灵魂和筋骨都被玷污了,而我们——我——却什么也没做。 My son, my only boy. Defiled in soul and sinew and we—I—did nothing.

([客人们继续吃饭。达朗犹豫了一下,咬了一口……然后干呕起来,筷子发出咔哒咔哒的声音。] / [The guests resume eating. DÀ LÁNG hesitates, takes a bite … then gags, her chopsticks clattering].)

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 这味道——! This taste—!

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([微笑] / [Smiling].) 公主,您认得它吗? Do you recognize it, Princess?

([倒吸一口气。皇后僵住了,半嚼的饺子从她的嘴唇上滴落下来。] / [Gasps. The Empress freezes, a half-chewed dumpling dripping from her lips].)

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 ([不是问题。] / [Not a question].) 我的女儿们—— My daughters—

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([平静地] / [Calmly].) 母亲应该知道自己血液的味道。 A mother should know the taste of her own blood.

SÀTŪN / 萨囤 ([吐食物。] / [Spitting food].) 亵渎!这是……亵渎! Blasphemy! This is... desecration!

DÀ LÁNG / 大狼 ([喘着气,紧紧抓住桌子。] / [Gasping, gripping the table].) 里面……有东西……在动……! It... hurts... inside... something... moving...!

SÀTŪN / 萨囤 ([惊慌地转过身] / [Turning in alarm].) 坚持住,我们会得到帮助的! Hold on, we'll get help!

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 哦,是的,正义即将到来。 Oh yes, justice is coming.

([一片混乱。群臣呕吐。可汗使者哀号。达朗尖叫起来,腹部膨胀、破裂,流出腐烂和焦黑的内脏。她在哀号中死去,尸体仍在咀嚼自己的舌头。天牧转身对着巴希拉吐口水。] / [Chaos erupts. Courtiers vomit. The Khagan's envoy wails. DÀ LÁNG screams as her belly swells, splits— spilling corruption and blackened viscera. She dies mid-wail, her corpse still chewing its own tongue. TIĀN MǓ turns and spits on BǍ XĪ LĀ].)

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 ([干呕着,向后退去] / [Retching, scrambling back].) 不——不,这不是——!我才不——! No—no, this isn't—! I never—!

([巴希拉转身逃离了院子。他的十字架掉在地上,摔得粉碎。没有人阻止他。] / [BǍ XĪ LĀ turns and flees from the courtyard. His cross clatters to the ground—shattering. No one stops him].)

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([在他身后喊道] / [Calling after him].) 快跑,神父。你的末日已经把你抛弃在你的盛宴残渣里了! Run, priest. Your apocalypse has abandoned you in the crumbs of your feast!

([铁古向前迈步,拔出刀子跟随,但天牧举起了一只手。] / [TIĚ GŪ steps forward, drawing her blade to follow, but TIĀN MǓ raises a hand].)

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 (CONT'D) 不,让他跑吧……现在。 No. Let him run … for now.

([天母走到儿子身边,轻轻摸了摸他的额头,然后撕下符箓。天佑的尸体发出一声叹息,如万只死蟋蟀同时低鸣,随即化为尘土,随风而散。] / [TIĀN MǓ walks to her son. Gently, she touches his brow. Then she tears the talismans free. TIĀN YÒU'S corpse exhales—a sigh like a thousand dead crickets—then crumbles to dust. The wind carries him away].)

SÀTŪN / 萨囤 ([站起来,气得浑身发抖] / [Rises, trembling with rage].) 你以为这样就能证明你正义?你不过是这腐败世界中另一团腐肉! You think this proves you are righteous? You are just another piece of rotten meat in this corrupt world!

([随着达朗腐烂的尸体最后一次抽搐,庭院中一片寂静。随后,从墙外传来号角声、马蹄声和战鼓声。铁鹰虽然血迹斑斑,但却取得了胜利,身后跟着一队蒙古战士和叛逆的边防将领。] / [A beat of silence falls over the courtyard as DÀ LÁNG'S corrupted corpse twitches one last time. Then, from beyond the walls: a cry of horns. The sound of hooves. War drums. TIĚ YĪNG enters, bloodied but victorious, followed by a battalion of Mongol Warriors and Rogue Border Generals].)

TIĚ YĪNG / 铁英 城门敞开。天命已然在此腐朽。我们不征服——我们只是扫荡。 The city gates lie open. The Mandate of Heaven has rotted here. We do not conquer—we scour.

SÀTŪN / 萨囤 ([挑衅地] / [Defiant].) 你竟敢把外国狗带进我的宫里? You dare bring foreign dogs into my court?

TIĚ YĪNG / 铁英 狗?也许吧。但我们还是会咬人。 Dogs? Perhaps. But we still bite.

([萨顿咆哮着,猛扑过去——但一支蒙古长矛刺穿了她的喉咙。她在咯咯的笑声中死去,鲜血溅满了宴会桌。她的身体倒在达朗身边。] / [SÀTŪN snarls, lunging—but a Mongol spear pierces her throat. She dies gurgling laughter, her blood splattering the banquet table. Her body collapses beside DÀ LÁNG].)

TIĚ YĪNG / 铁英 (CONT'D) 暴君已死,唯有风暴残存。而风暴,从不请求许可。 The tyrant is dead and only the storm remains. And storms do not ask permission. ([铁引望向巴希拉逃出的宫门。] / [TIĚ YĪNG looks toward the palace gates where BǍ XĪ LĀ fled].)

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 我还有一道菜要上。 I have one more course to serve. ([天牧甩开围裙,拔出武器,用一只好手将残链绑在手腕上。] / [TIĀN MǓ tosses aside her apron and draws out her weapon. Her one good hand straps her stump-chain to her wrist].) ([平静地] / [Quietly].) 让甜点成为判断。 Let the dessert be judgment.

([天牧走进了燃烧的夜色中。] / [TIĀN MǓ walks off into the burning night].)

֍

[第四幕,第二场] [ACT IV. SCENE II]

[漆黑天幕下的诅咒绿洲。星辰寒冷刺骨,悬得近乎压人。枯树如骸骨,枝桠扭曲,如亡魂向天哀求赦免。沙地发出嘶嘶声响,风如骨骼摩擦般低语。水池泛着病态而诡异的光芒。池边裂开一道深渊——那是天佑气息破碎之地。深渊之下,某种可怖之物潜伏等待。] [The cursed desert oasis under a black sky. The stars hang too close, too cold. The trees are skeletal, clawing upward like the dead begging absolution. The sand hisses. The wind whispers like shifting bones. The pool glows with a sickly, unnatural light. A dark pit yawns beside it—the place where TIĀN YÒU'S qi was shattered. Something waits beneath.]

([巴西拉上场。] / [BǍ XĪ LĀ enters].) ([他原本华贵的传教士长袍如今破烂不堪、污秽不洁。他紧紧捂着胸口,那是他十字架原本所在的位置——如今空空如也。他踉跄而入,气喘如牛,满脸惊恐。] / [His fine missionary robes are torn and filthy. He clutches his chest where a cross once hung—now gone. He staggers, panting in terror].)

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 ([惊恐] / [Terrified].) 不……不不不……不能是这里!别是这里! No…no no no…not here! Not here! ([跌倒在地,手在沙里乱抓] / [Falls to the ground, clawing in the sand].) 这不可能……他们向我承诺过!皇后听我说了! This can't be…they promised me! The Empress heard me! ([带着狂乱的祈求] / [With frantic pleading].) 大郎!大郎!她明明……我明明已得教皇恩宠!圣印!火舌的赐福! Da'lang! She... I still have the Pope's favor! The Seal! The blessing of the Tongue of Fire! ([仰望天空] / [Looking up at the sky].) 他们都说我会赢!我信仰的神是真理!他不会抛弃我…… They all said I would win! The God I believe in is the truth! He will not abandon me…

([隐约传来金属刮地的拖行声,低沉而节奏分明。巴西拉骤然僵住。从漆黑扭曲的树影中,天母缓缓现身。] / [A faint, metallic dragging begins, low and rhythmic. He freezes. From the trees, TIĀN MǓ enters].) ([她步伐缓慢,链条拴在断臂上,拖曳沙地。她看上去更老,更疲惫,身体微微颤抖。然而,空气却因她的到来而沉寂无声。] / [She moves slowly, dragging her chain-bound stump through the sand. She looks older, wearier, trembling. Yet the air stills around her].)

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([嗓音低沉如石碾] / [Low, raspy].) 这片土地的神灵,没你想象的那么容易消亡,巴西拉。 The spirits of this land are not so easily dismissed, Bǎ Xī Lā. 它的神明……还在饥饿。 And its gods…they hunger. 你以为你会死在教堂里,香气缭绕? Did you think you'd die in a chapel, perfumed with incense? 衣冠整齐,沐光而逝,被你的主亲吻接引? Righteous and clean, kissed by your god? ([缓步前行,链条拖行声刺入耳中] / [She takes another slow step, the chain dragging].) 不。 No. 你会死在这里。死在你播下恶果之地的泥土与污秽中。 You will die here. In this filth where you sowed your evil.

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 ([惊恐倒退,注意到她的状态] / [Startled, defensive].) 是你!你追我到这?你流血了……你连站都站不稳了…… You! You followed me? You're bleeding. You're... barely standing ... ([突现疯狂之光,拔剑] / [He draws his sword—erratic confidence flaring].) 我还有胜算!我主与我同在!击倒你这妖女! I still have the edge! My God is with me! He will strike you down, witch!

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([发出干涩冷笑] / [Chuckling, dry as sand].) 你的主……遥不可及。 Your god seems... distant. 而我的神们……近在咫尺。 Mine, however, are very near. 来吧。来夺你所谓的'优势'吧,传教士。 Come then. Take your 'edge,' priest.

([他们开战。] / [They fight].) ([巴西拉怒吼着猛冲,剑势狂乱,全凭蛮力毫无章法。天母不与他硬碰,只巧妙闪避。一息之距,一旋之差,一转之间——他的剑只斩中衣角、风声与寂静。铿然一声——她用链条挡下他的劈砍,火花四溅。一甩之间,链头缠住他的脚踝。他踉跄后退,一树枝猛然刺破他的衣袖。] / [BǍ XĪ LĀ charges—his blade slashes wildly, strength without technique. TIĀN MǓ does not counter—she evades. A breath's lean, a pivot, a turn—his sword cuts only cloth, wind, silence. CLANG. Her chain blocks a direct strike. Sparks hiss. A flick—his ankle is caught. He stumbles. A tree limb spears his sleeve].)

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 ([喘息着,兴奋] / [Panting, excited].) 看见了吗?你那虚假的力量正在衰退! See? Your false power is fading! 你那魔鬼的法术失效了! Your devilish spells are failing! 你不过是个女人,一个老寡妇! You are only a woman, an old widow! 一个在神脚下爬行的野兽!你那些泥胎木偶的伪神祇早就该死! A beast crawling at the feet of God! Your clay puppet gods should have died long ago!

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 那么就和我一起流血吧,牧师。 Then bleed with me, priest. ([她动了。起初很慢——然后越来越快。铁链划出一道弧线,在空中轰鸣。他猛扑过去——她不在。他转身——太迟了。链风啸过——大腿。回扫——侧腹。反劈——后背。] / [She moves now. Slowly at first—then faster. The chain arcs in figure-eights, whispering through the air. He lunges—she’s not there. He turns—too late. The chain whistles – hits his thigh. Sweeps his flank. Counter-slash across his back].) ([水池仿佛叹息一声,荡起层层涟漪,幽光乍现。他气喘吁吁地退入池边,眼神迷茫。] / [The pool sighs. Ripples flash with ghostlight. He backs into it, panting, uncertain].) ([枯树虬曲,幻象骤生——他竟见天佑缚于树下,泣血哀嚎。] / [The dead tree suddenly twists and a hallucination appears - he sees TIĀN YÒU tied to it, crying and wailing].)

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 ([低语,带颤] / [Voice thin, broken].) 这……这里……那个男孩…… This... here... that boy... 那对孪生姐妹……把他带到……这里…… The Twins... brought him... here...

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([声音骤变,如冰刃] / [Voice suddenly changes, like an ice blade].) 没错。 Yes. ([她挺直腰身,气息归稳,目光如刃] / [She straightens her back, her breath becomes steady, her eyes are like blades].) 你将我儿的魂魄在此撕裂。你将他奉献给那地狱之口。 You tore my son's soul apart here. You offered him to the mouth of hell. ([她挺直身躯,不再衰弱,不再疲惫。风停了。沙也安静地倾听。她高举链条,此刻,它不再是负担,而是利刃。] / [She straightens. No longer frail. No longer tired. The wind stills. The sand listens. She raises her chain—not as burden, but as a blade].) 斩魂之缚——斩断灵魂的束缚。([一位母亲的复仇,被炼化为武学。] / [A mother’s vengeance perfected into technique].) The Binding That Severs the Soul. ([她旋身一转,链光如电。他斩出一剑——却扑了空。她已绕到他身后——啪!右脸一道血痕。啪!左脸又一道。血如对称的面具,在他脸上浮现。] / [She spins once. The chain flickers. He slashes—she is gone. Behind him— Whip—his right cheek. Whip—his left. Twin lines of blood. A mask].) ([语气如鞭] / [Tongue like a whip].) 你曾许诺报偿。你谈过天恩。 You promised rewards. You talked about grace. 那你来——用金银收买我吧,传教士。 Then come on—buy me with gold and silver, missionary. 你的命换财宝。公平的交易,不是么? Your life for treasure. A fair deal, isn't it?

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 ([捂脸,语无伦次] / [Sobbing, babbling].) 是!金子!银子! Yes! Gold! Silver! 在聂斯脱里那边藏着的财宝!西方来的珠宝!都给你! Nestorian gold! Jewels from the West! All for you! ([链条轻弹,右脸一痕血线。] / [The chain flicks, a streak of blood runs down the right side of his face].)

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([冷笑] / [Coldly amused].) 你来吧。承诺我一个天堂的位置。你们常说的,在你主的右边,永远的荣耀。 Then promise me salvation. Place me next to your god, at his right hand. For eternity. ([链条再次飞出,死死缠住他的脖子。他挣扎窒息,踉跄着退到深渊边缘,脚下沙土不断崩塌。] / [The chain lashes again, coiling his neck. He chokes. He stumbles—teetering at the pit’s edge].) ([倾身靠近,愤怒地低语] / [Leaning close, whispering with wrath].) 巴希拉,请满足我的一切愿望吧。 Offer me everything I ask for, Bǎ Xī Lā. 一切。 Everything. 像你这样的灵魂,要付出什么代价? What is the price for a soul like yours?

BǍ XĪ LĀ / 巴希拉 ([哽咽、挣扎] / [Gurgling].) 什么都行!我命也给你! Anything! I'll give you my life! 我做你奴仆都行…… I’ll be your slave...

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([怒啸,声震天地] / [Suddenly roaring, voice quaking of grief].) 我要把我的孩子们还回来,你这个狗杂种! I WANT MY CHILDREN BACK, YOU SON-OF-A-DOG! 我要我的手! I WANT MY HAND! 我要你凭那邪信窃走的一切! I WANT EVERYTHING YOU STOLE WITH YOUR CURSED FAITH! ([她缓缓地,从断臂上解下链条。动作坚定而冷静。链落。人坠。四野寂静无声。] / [She unbuckles the chain from her stump. A single, deliberate motion. It falls. He falls. Silence].) ([没有冲击。没有尖叫。只有消失。] / [No impact. No scream. Just absence].) ([她孑然而立。抬头望向冷漠无情的星辰。她低头看向自己的断臂,看向深渊,然后转身望向东方——城市的方向。] / [She stands alone. The stars stare down—distant, indifferent. She looks at her stump. At the pit. Then to the east—toward the city].) ([低语] / [Quiet].) 我已一无所有。没有喜悦。没有够甜的复仇。 No joy. No vengeance sweet enough. 但,我的孩子……天佑……我的女儿们……你们可以安息了。 But my children... Tiān Yòu... My daughters... You can now rest. ([她转身,独自踏上归途。形单影只,却终得完整。] / [She turns. Begins walking. Alone, but complete].)

֍

[尾声] [EPILOGUE]

祖剑堂密室 Ancestral Sword Hall Crypt.

([大殿幽暗,空气凝滞。石骆驼沉睡于尘埃之下。祖剑微微泛光。新香在祭坛上袅袅燃起。铁鹰、铁姑与天母缓步而出,立于城门前。他们身后,立着一块崭新的纪念碑。碑上刻着:「天佑之碑」] / [The hall is dark, the air still. Stone camels sleep beneath layers of dust. The ancestral swords gleam faintly. New incense burns at the altar. TIĚ YĪNG, TIĚ GŪ, and TIĀN MǓ exit and stand before the City Gates. Behind them stands a fresh memorial stone. Carved upon it: The Tablet of TIĀN YÒU].)

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 铁家之子。 Son of the House of Iron. 他身负母伤, He bore the wound of his mother, 以我之苦书写预言。 and wrote my pain into prophecy.

TIĚ GŪ / 铁姑 他从未举过刀—— He never lifted a blade— 却也让他在此与姐妹们安眠。 And yet let him sleep here with his sisters.

TIĚ YĪNG / 铁英 ([低声] / [Quietly].) 他不需要剑。 He didn’t need a sword. 但他无需剑也勇敢。 But was brave without one.

([风起,呜咽如哭。] / [The wind begins to howl].)

TIĚ GŪ / 铁姑 ([轻轻地] / [Lightly].) 都城那边……有人在议论。 There’s talk ... in the capital. 说我该戴上凤冠。 That I should wear the Phoenix crown.

TIĚ YĪNG / 铁英 我会在你右手而骑。 I’ll ride at your right hand. 但你需要的不只是将军。你需要一个记得我们失去过什么的朝廷。 But you’ll need more than a general. You’ll need a Court who remembers what we lost.

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 ([淡淡一笑] / [Smiling faintly].) 那就去建一个吧。 Then make one. ([顿。] / [Beat].) 我已完成了我的部分。 I’ve finished my part.

([风势渐强。远方沙暴翻卷,吞噬地平线。] / [The wind grows louder. A sandstorm curls along the horizon].)

TIĚ YĪNG / 铁英 ([焦急] / [Concerned].) 城门—— The gates— 我们该关上它。 We should close them.

([天母越过他们,走出门槛。] / [TIĀN MǓ steps out ahead of them, across the threshold].)

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 敞着吧。让死者有一道门。 Leave them open. The dead should have a door. 他们也需要这样的地方。 They’ll need a place like this.

([天母回首。铁鹰与铁姑仍立于城中,肩并肩,立于昏光之下。天母抬手一挥,又放下。沙暴渐渐吞没苍穹。] / [TIĀN MǓ turns. TIĚ YĪNG and TIĚ GŪ remain in the city, standing side by side in the muted light. TIĀN MǓ lifts her hand once, then lowers it. The sandstorm begins to swallow the sky].)

TIĀN MǓ / 天母 (CONT'D) ([低语] / [Softly].) 唤我之名——我之魂必应。 Speak my name—and my spirit will answer.

([她步入风暴。身影渐隐,足迹无痕。无尸,无葬,唯有其传。] / [She walks out into the storm. Her figure fades. Her footsteps leave no mark. There will be no bones, no burial. Only the story].)

[结束] [END]

֍

GLOSSARY OF TERMS

Bái Sī [白丝]: Literally "White Silk." Youngest daughter to the late Empress.

Bái Wúcháng [白无常]: "White Impermanence." One of the two Heibai Wuchang, deities in Chinese folk religion responsible for escorting spirits of the dead to the underworld. Often depicted in white robes.

Bǎ Xī Lā [巴悉拉]: The Chinese transliteration for "Basilas" or a similar European name; in this play, an evil Nestorian Christian missionary.

Dà Láng [大狼]: Literally "Big Wolf." Head of the Five Poisons Sect.

Dāntián [丹田]: "Cinnabar field" or "Elixir field." Energy centers in the body, crucial in traditional Chinese medicine, martial arts, and meditation for the cultivation and storage of Qi. Often refers to a point in the lower abdomen.

Dàzhùi [大椎]: "Great Hammer." An acupressure point on the spine, considered a vital point.

Feng Shui [风水]: Literally "Wind-Water." A traditional Chinese practice of arranging spaces to achieve harmony with the natural world and harness positive energy flows (Qi).

Five Poisons Sect [五毒教]: A fictional martial arts sect common in wuxia, specializing in poisons and often portrayed as villainous. The "Five Poisons" traditionally refer to the centipede, snake, scorpion, toad, and spider.

Five-Eyed Toad [五眼蟾蜍]: A mythical toad, often associated with poisons, dark magic, or wealth in Chinese folklore. The "five eyes" imply heightened perception or a connection to the five elements.

Hēi Dú [黑毒]: Literally "Black Poison." One of Dà Láng's daughters.

Hēi Wúcháng [黑无常]: "Black Impermanence." One of the two Heibai Wuchang, deities in Chinese folk religion responsible for escorting spirits of the dead to the underworld. Often depicted in black robes.

Huī Dú [灰毒]: Literally "Grey Poison." One of Dà Láng's daughters.

Jade Empress [玉皇]: Often refers to the Jade Emperor (玉皇大帝, Yù Huáng Dà Dì), a supreme deity in Chinese folk religion and Taoism. Here, potentially gender-bent or a specific title.

Jade Gate [玉门]: Yumen, a historical frontier pass in Gansu province, China, marking an entrance to the Western Regions on the Silk Road. Symbolically, a gateway or border.

Jade Scepter / Jade Order [碧玉令 / 玉令]: A symbol of authority or imperial decree, made of precious jade.

Jǐzhōng [脊中]: "Center of the Spine." An acupressure point on the spine, considered a vital point.

Jinyiwei [锦衣卫]: "Brocade-Clad Guard." Imperial secret police and bodyguards during the Ming Dynasty in China, known for their power and often feared.

Kowtow [叩首]: The act of deep respect shown by kneeling and bowing so low as to touch one's head to the ground.

Lán Dú [蓝毒]: Literally "Blue Poison." One of Dà Láng's daughters.

Leviathan [利维坦]: A biblical sea monster, here used by Bǎ Xī Lā to invoke a sense of monstrous, chaotic power.

Lǐguān [礼官]: "Officials of Rites." Court officials responsible for ceremonies, protocol, and rituals.

Mandate of Heaven [天命]: An ancient Chinese political and religious doctrine used to justify the rule of the Emperor. Heaven grants the emperor the right to rule, but this mandate can be lost if the ruler becomes unjust or ineffective.

Mìngmén [命门]: "Gate of Life." A crucial acupressure point on the lower back, considered a vital center of Qi.

Nestorian [景教]: An early branch of Christianity that spread along the Silk Road and reached China (where it was known as Jǐngjiào, 景教).

Nine Tripods [九鼎]: Legendary bronze cauldrons said to have been cast by Yu the Great of the Xia dynasty, symbolizing the sovereignty and unity of ancient China. Possessing them signified legitimate rule.

Paper Effigies [纸马 / 人像]: Paper representations of objects (like horses, servants, money) burned as offerings to the dead in traditional Chinese funerary rites, believed to provide for the deceased in the afterlife.

Phoenix [凤]: A mythical bird in Chinese mythology, symbolizing virtue, grace, and often associated with the Empress or auspicious occasions.

Qi [炁]: "Vital energy," "life force," or "spiritual breath." A fundamental concept in Chinese philosophy, medicine, and martial arts, believed to flow through all living things. Its destruction can lead to death or a zombie-like state.

Ren Meridian [任脉]: The "Conception Vessel," one of the extraordinary meridians in traditional Chinese medicine, running along the front midline of the body.

Sàtǔn [萨吞]: Eldest daughter to the late Empress, her name might be a transliteration or a chosen powerful-sounding name.

Spirit Tablet [灵位]: A plaque inscribed with the name of a deceased person, used in ancestral worship to house the spirit of the ancestor.

Tao [道]: "The Way" or "The Path." A fundamental concept in Chinese philosophy, particularly Taoism, referring to the natural order of the universe, the underlying principle of existence.

Tiān Mǔ [天母]: Literally "Heavenly Mother" or "Sky Mother." An elderly female general, the protagonist.

Tiān Yòu [天佑]: Literally "Heaven's Blessing" or "Protected by Heaven." Tiān Mǔ's son.

Tiě Gū [铁姑]: Literally "Iron Aunt." Court official and Tiān Mǔ's sister.

Tiě Líng [铁翎], Tiě Lián [铁链], Tiě Xuè [铁血], Tiě Yīng [铁英]: Daughters of Tiān Mǔ. Their names often incorporate "Tiě" (Iron) and another character: Líng (Feather/Plume), Lián (Chain), Xuè (Blood), Yīng (Eagle/Hero).

Wuxing [五行]: The Five Elements or Five Phases (Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, Water). A conceptual scheme in traditional Chinese thought used to explain a wide array of phenomena, from cosmic cycles to interactions within the human body.

Xuánnǚ [玄女]: The "Mysterious Woman" or "Dark Woman." A Chinese goddess of war, sex, and longevity, often credited with aiding historical figures in battle.

Xuè Shà Xīng [血煞星]: "Blood Fiend Star" or "Star of Baleful Blood." A malevolent deity or astrological influence associated with bloodshed and disaster.

Yahweh [耶和华]: The Hebrew name for God in the Old Testament, used by Bǎ Xī Lā.

Yellow Springs [黄泉]: The Chinese mythological underworld or realm of the dead.

Yùshǐ [御史]: Censor or Imperial Inspector. High-ranking officials in imperial China responsible for investigating and impeaching other officials, maintaining discipline and protocol.

Zhanmadao [斩马刀]: "Horse-Chopping Saber." A type of long, single-edged Chinese sword, often wielded with two hands, known for its power.

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gormenghast ↳ circles, prisons, claustrophobia

“That is Andrema, the lyricist — the lover — he whose quill would pulse as he wrote and fill with a blush of blue, like a bruised nail. His verses, Fuchsia, his verses open out like flowers of glass, and at their centre, between the brittle petals lies a pool of indigo, translucent and as huge as doom. His voice is unmuffled — it is like a bell, clearly ringing in the night of our confusion; but the clarity is the clarity of imponderable depth — depth — so that his lines float on for evermore, Fuchsia — on and on and on, for evermore. That is Andrema … Andrema.”

— Mervyn Peake, Titus Groan

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

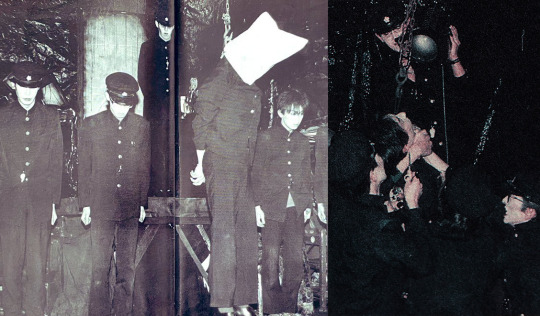

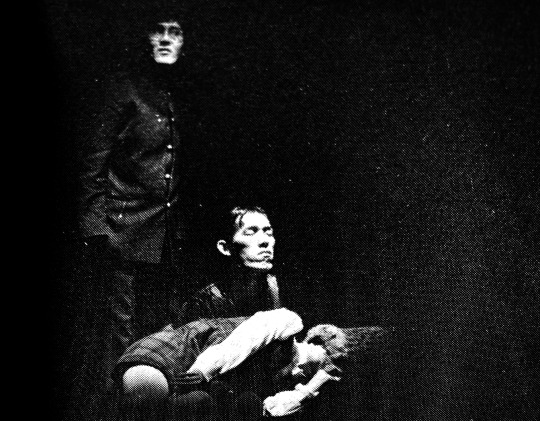

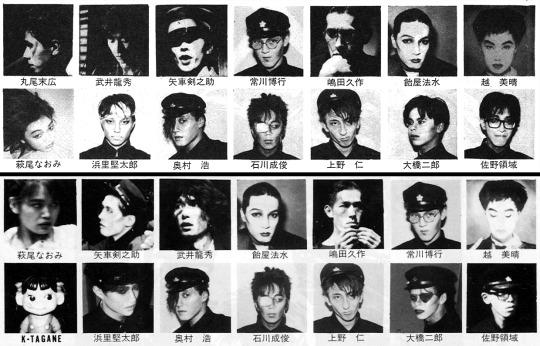

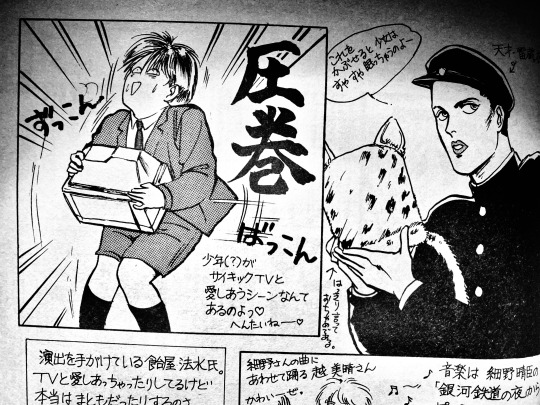

Most of the known images from the Tokyo Grand Guignol’s Galatia Teito Monogatari. Despite its titular connection, the play has virtually no relation with the Teito Monogatari series. By the time of its conception, Ameya and Tagane had already conceived a unique play titled Galatia, and Ameya reworked the play into a loose adaption of the series after being offered a grant by a publisher of the Teito Monogatari series. On Ameya’s own admission, he only read a rough synopsis that mentioned the destruction of Tokyo as a central plot point. A sort of black sheep in the Tokyo Grand Guignol’s body of work with its notable lack of coverage, Galatia is in many ways a prototype to Lychee that also doubles as a loose Maruoesque reimagining of the first Godzilla film in its themes and sound design. Set in the household of the Shirai family, it follows the efforts of a mad Nazi scientist named Helmut Shirai to create a machine that would alter the climate of Japan. He openly despises the humid weather that Japan is known for, spending his days inside a freezer to avoid the smoldering temperatures around him. His machine is nearly complete, but he needs a unique fuel source, one that isn’t gasoline or electricity. That’s when Yasunori Katō, a youthful imperial army general, visits the Shirai household to tell Helmut about Doctor Akihiko Hirata. Described as being an expertly skilled yet humble pioneer of the sciences, Katō believes that Hirata had already created the exact fuel source Helmut is seeking. Helmut and Katō conspire a plot to abduct Hirata through a tea party between the Shirai family and Hirata family, their agreement being underscored by a sinister piano stinger from Robert Wyatt’s soundtrack to The Animals Film. Through the subsequent scenes, it’s slowly revealed that the fuel source is actually Galatia, a robotic doll Hirata created for his baby sister, Miharu Hirata. Miharu has down syndrome, and Akihiko created a unique formula that causes the doll to operate from her chromosomes. Akihiko is protective of his sister in a manner that can be read as both wholesome and potentially sinister in motives. He allows the Shirai family to brutally torture him in attempts to keep Miharu’s connection with Galatia a secret, eventually resulting in Akihiko’s death when Helmut puts a special device over Akihiko’s head that renders his biological essence to a bloody pulp. The play ultimately wraps on a chaotic bloodbath. Successfully taking Galatia away from Miharu, Katō and Helmut prepare to activate the weather machine before an unexpected reunion ensues between the Helmuts and the Hiratas. Miharu recognizes her doll in the weather altering device, and upon her throwing a tantrum, Galatia brutally slaughters nearly the entire cast. It’s implied that Galatia becomes an even greater machine upon activation, with the stage going black as the room is filled with the sounds of booming machinery, titanic hisses of steam and the collective wails of the protagonists. With the aftermath eventually revealed, Katō emerges as the lone survivor, welcoming the viewer to what he calls the "new imperial capital" as he activates the weather altering machine, bringing forth a new ice age.