Photo

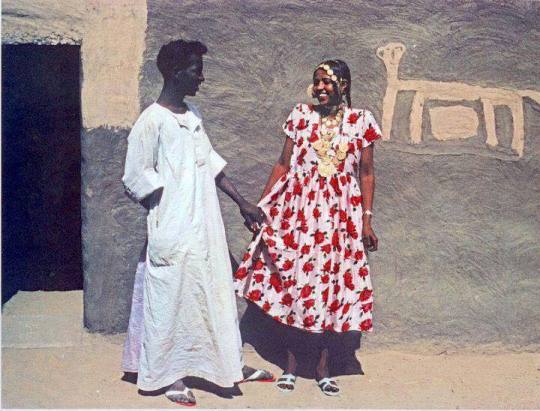

fucking golden

Mahmoud Al Obaidi | b. 1966 Iraqi

188 notes

·

View notes

Text

WAW-WEE

I got some cordyceps sinesis capsules from Mountain Rose Herbs to try, took one today, awwwww man, they should be handing that stuff out instead of adderal, ritalin etc.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sample from my #LateNigthWorkClub film “ Al Hurriya الحرية Freedom “ Animated by @martin-robic // http://martin-robic.tumblr.com/ Film coming… getting there ……… !!

167 notes

·

View notes

Link

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“ Intimite de la Sicile” par Willy Roettges, 1961.

Vita quotidiana, donne siciliane.

Everyday life and women.

36 notes

·

View notes

Quote

You were born in Raqqa in 1961. What were your political and intellectual influences as a young man? In 1980 you were arrested for your political activism and spent 16 years behind bars. What exactly were you arrested for? What was your group doing in that period? What was Syrian political life like at that time? Yassin al-Haj Saleh: I was a member of one of the two communist parties in Syria when I was a student at the University of Aleppo, the Syrian Communist Party-Political Bureau. It opposed to the regime of Hafez Assad, and was struggling for democracy. I was influenced by thinkers like the two late Syrians Yassin al Hafez and Elias Murqus, and the Moroccan historian and political theorist Abdallah Laroui. To those of us seeking a better understanding of our social and historical situation, they offered a non-dogmatic Marxism with an orientation to our society and cultural problems. Under their influence, I decided I wanted to be a writer. We found ourselves enthusiastic about the Euro-communism of the 1970s and critical towards the Soviet Union. But our political identity was mainly built on our experiences of struggle against the tyrannical rule of Assad, the father. It combined a traditional leftist affiliation with a deep commitment to the people and an aspiration for freedom. Before 1980 one could hardly speak of a political life in Syria. There was an alliance of seven parties, including the official Communist Party (who relied heavily on the Soviets). The alliance, the National Progressive Front (NPF), was under the leadership of the Ba’ath Party, and it was supposedly the frame for political life in Syria. Actually it was the frame for political death. Other groups who were steadfast in opposing the regime were sent to jail. So prisons and NPF have been the political institutions in the country for forty-one years now. At the political level, we harshly condemned the regime and considered it to be responsible for the “social and national crisis” that broke out in the country between 1979 and 1982. At that time, the regime of Hafez Assad showed increasingly fascist tendencies—organized violence against any independent social or political activities, building “popular organizations” to contain society, from school children to universities to women to trade unions. It also fostered entrenched, widespread nepotism with a blatant sectarian element in it, and created a cult of Assad via its media, military, educational institutions, and in public spaces (statues, banners, photos, songs, “spontaneous marches”). In a few years, this led to a big political and social crisis and a violent struggle between the regime and the Muslim Brotherhood. By the time the regime won this battle through bloody means, which was widely ignored at the international level, it was already on its path of crushing all the remaining forms of political and cultural life. The Syrian Communist Party-Political Bureau denounced the outburst of fascism and spoke in favor of a democratic change to enable Syria to avoid violence and to open the political system to the people’s organizations and initiatives. We took active part in the protests in many Syrian cities in 1980. I was myself a participant in those protests at the University of Aleppo. Afterwards, I was forced to live in hiding for two months until I was arrested on December 7, 1980. I was only one of hundreds of members arrested. I was less than twenty years old at that time and spent sixteen years in prison. [Syrian opposition leader] Riad at-Turk spent nearly eighteen years in solitary confinement. After prison I became a writer and participated in many activities of the opposition. Sixteen years in prison is a long time, but it was a formative experience for me as a public intellectual and as an ethical agent in the struggle for change. At the same time, it was an emancipatory experience; through suffering, learning, and struggle I broke out of some of my internal prisons: that of narrow political affiliation, of rigid ideology, and that of the intellectual’s ego. Perhaps the second most important influence on my political identity is the revolution that began in March 2011 and the open-ended and multi-leveled struggle that is going on in the country. I stayed in hiding in Damascus for two years, and for another six months in other parts of the country. My role was that of an intellectual and writer, not of a politician or a political activist. In the coming years, I intend to work on the cultural dimensions of the Syrian revolution since I believe culture could be a strategic field for our struggle for freedom and against fascism, both the Assadist and Islamist versions.

The Conscience of Syria: An Interview with Activist and Intellectual Yassin al-Haj Saleh (via bustan-wuroud)

57 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Jamil Ghanim - Reveries en Nihawand en Fa (Luth Au Yemen Classique Ud - 1979)

56 notes

·

View notes