Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Image compilation about my OC Hwinlaer for my Silmarillion & LoTR fanfic, Gwatha i Dû. All of them are AI-generated on ArtBreeder, though I corrected the first woody one so there is a braid in the hair. Old batch can be found here.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sorry about the text in the bottom left corner, made these when I was still new to my current phone in 2020 and had no idea how to make the script disappear. Fortunately, I was so annoyed by it that I found the related option...

0 notes

Text

Commentaries concerning Elven Naming Traditions of Middle-earth on RealElvish.net

Recently I read this (https://realelvish.net/naming/middleearthelves/) article on RealElvish.net because I was curious about it and, in a way, I was amused by it. It amused me how epically the article’s writer has failed. Or more like, I would have been happier if I was indeed amused. Truth is, after I finished reading I was enormously embarrassed on the writer’s behalf and could not quite imagine where the person in question had sucked all this stuff out.

So, I decided to let the steam off by writing a critique about it. Let us proceed from paragraph to paragraph. This will seem more like some kind of commentary while reading the actual article as I decided to cite it so that you, folks know what I am talking about.

Elven Naming Traditions of Middle-earth If you haven’t read the essay on the Elven naming traditions of Valinor, go back and read it, then read this essay. The conclusions and terminology used in this essay will make more sense if you do so.

If you would prefer to read the mentioned article yourself then you can do so by clicking on the underlined part, but as my humble self is already familiar with the –correct– Valinorean elves’ naming traditions, therefore I did not have to read that essay, but to be fair to those who are not, here is the shortened, simplified version of what they had wrote in there:

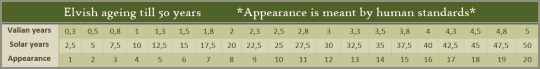

The Valinorean elves, specifically the Noldor, had four types of names or essi in Quenya, their language. (The language of the Sindar is referred to as Sindarin.) The three first were called anessi or ‘given names’ as they were bestowed upon an elf by somebody else, but the last type is the cilmessë or ‘chosen name’ as this was chosen by the elves themselves.

The first anessë can be translated as ataressë since it is called ‘father-name’. This was given by the child’s father and it was a public name, so anyone could address a Noldo by it. The second anessë is the amilessë or ‘mother-name’ as this was bestowed upon children by their mothers after they became a bit older. This name too was a public one, though more descriptive and kind of prophetic in its nature. The third anessë is the epessë or ‘after-name’ that could be given by anybody and it was a sort of nickname, if you will. Finally, there was the cilmessë, the name that reflects a Noldo’s personal linguistic tastes. This was a private name and only those close to the elf used and it was considered rude for anyone else who did not know the person well.

So, this is the –tremendously– watered-down version, but please, worry not, I will not begrudge you if you do not believe me and choose to look the topic up. In fact, I do recommend the mentioned essay as it is very helpful and, as you will see later, its insightfulness creates a harsh contrast with this article. Although the constant miswriting of the Quenya accents gets on my nitpicking nerves…

If you are curious to know more about the naming conventions of the Valinorean elves then I also recommend the articles on TolkienGateway.net titled essë (https://tolkiengateway.net/wiki/Ess%C3%AB) and Elven customs (https://tolkiengateway.net/wiki/Elven_customs). These three articles together help to have more understanding of the naming traditions of elves living in Aman, especially as RealElvish got a few things wrong regarding which names are public and which are not, plus making up some other things along the way.

Of the naming traditions of the Eldar who lived in Valinor, we know much. However, the naming traditions of the Úmanyar (those who didn’t go to Valinor and stayed in Middle-earth) are largely undocumented. Though Tolkien never explicitly described them, we can guess by looking at their names.

This is absolutely true and there is absolutely nothing wrong with this paragraph, only that later the writer had beautifully cornered themselves in the following text.

The Elves of Beleriand are the ones most likely to have naming traditions echoing the traditions in Valinor, seeing as they were the closest to Valinor and they had trade and communication going between them. Therefore, when Doriath was conquered and the Sindar fled deeper into Middle-earth to live in the lands of other Telerin Elves, they brought these strong traditions and their language with them. Since the language was adopted, it doesn’t seem too strange that the naming traditions would come along too.

Okay, now it is time to scream: “Silmarillion spoiler alert!” If you are not familiar with the history of elves then I have to recommend you, dear readers, to study it a bit, since the topic is quite complicated and would be too bothersome to explain it in length here. Although you will get some specifics nonetheless but for the sake of my own and your mental health I will merely assume you all know what I am talking about in this part, and be warned that it will be a very long tirade. You have been warned…

The very first part of the sentence seemed innocent enough, but the next one about trading and communication just blew the fuse for me. I found it confusing because, if you think about it, if this had been a canon fact, then a lot of events would have developed very differently compared to what was originally written by Tolkien.

If there would have indeed been trading and communication going between Aman and the realms of Beleriand, then how come the Sindar suffered so much that they thought the Feanorian Noldor their saviours when Morgoth’s army was ordered to confront them, thus enabling the strained Sindar forces to win the First Battle? Because if there was any kind of communication between the two continents then:

1) The Sindarin and Quenya Elvish dialects had never become so different from each other due to the constant transmission of news and there would have been elves living in the Blessed Realm who spoke Sindarin. Naturally, there would have been plenty of discrepancies still, but there would have been more similar loanwords they shared as well since they would inevitably assimilate phrases and expressions.

2) The Sindar would have been capable of speaking with the Noldor without the Noldor ever properly learning Sindarin and translating their essi into those Sindarin equivalents and then Quenya would not have been considered a dead language in the Third Age because of disuse in speech.

3) Círdan, Thingol, Lenwë and the other mention-worthy elven lords, would have been informed about Morgoth’s misdeeds in Aman, thus the dwellers of Beleriand would not have been so surprised by his return.

4) Mentioned elven leaders would have also been informed about the First Kinslaying and so, they would have been completely aware of who the Noldor were and what have they done and there would have been totally no need to pester Galadriel (who was staying in Doriath as a guest) about why the Noldor had returned to the Hither Lands. This would be the case even if there was a (likely) pause in passing information between the continents during the Long Night after the Darkening of Valinor. Also, later, Thingol would not have banned Quenya because no ruler in their right mind would ever prohibit the language of an important trading partner.

Although this does not mean that there was not any kind of trade between Sindar and Noldor, but it is more likely to have happened after the arrival of the Exiles. And even if, at first, they were viewed as God-sent, after the Fëanorians proved to be way too haughty and Thingol learned about the first Kinslaying, I doubt that the Noldor would have been considered important trading partners. Let us not forget that Elu Thingol too was a monarch and had a prideful disposition due to that or else he would have not made the sycophant Saeros into his counsellor.

If there was commerce between the elves of Aman and Beleriand before the Exiles’ arrival then would the Sindarin king not be a bit more affable towards them? The Noldor after all, even with having their own agenda, ended up helping them turn the tables in a very perilous period. In this situation a potentate should have made as many allies as he could because Morgoth’s presence threatened them ceaselessly; the Moriquendi, more than any Elda could fathom, knew exactly just how cruel and devastating that could be. Though the elven tribes had travelled together for a while during the Great Journey, those times were merely a taste of the horror the dark forces were capable of. Moreover, the Eldar had the (far from perfect) protection of the Valar, but the Moriquendi had stayed behind and fended for themselves for practically long millennia.

But Elu Thingol, while not being hostile, had no care for the Noldor save for the children of Finarfin for they were his kin since their mother was Eärwen, daughter of Olwë who was his younger brother. Only the descendants of Eärwen was he willing to let into Doriath and those were five persons at the maximum: Finrod, Angrod and his son, Orodreth, Aegnor and Galadriel. It is clear that Thingol had found the preservation of his kin and loyal subjects more important than gathering confederates. (On a sidenote: Thingol was described as a good friend of Finwë so it is quite a mystery why he was so dismissive of the other Finweans.)

I do not know why he could not see the usefulness of a Noldo-Sindarin alliance. The Exiles were kinslayers indeed, but there were amongst them who regretted their actions. However, regardless of whether they were repentant or not, the Noldor had already proved to be a force to reckon with thus quite valuable in the fight against Morgoth. They also had both Ainur-reinforced technology and knowledge at their disposal; the Noldor were craftsmen and their skills were superior to the Sindar in that regard since they had the opportunity to directly learn from the Ainur. If Thingol could have put aside his pride he could have seen the bigger picture since a Beleriand-wide Noldo-Sindarin alliance would have been far more auspicious in the wars coming.

In The Silmarillion there are quite a few times when Thingol’s self-esteem had made things worse for his very own people he ought to protect. It gradually grows into arrogance and tethers on the edge of madness towards the end of his life. But this is another topic, so just let us say that Thingol had preferred something akin to ostrich policy: he did not deny that there was a problem (Morgoth), but he pretty much ignored it and did not give much afterthought to anything outside the borders of Doriath and refused to cooperate with the Noldor.

5) Finding a way back into Valinor and asking for the Valar’s help would not have been that big of a deal if there would have been continuous trade between Beleriand and Middle-earth. After all, trading routes are a sure way to get to any country and the technology of Valinor could have helped any realm in battles waged against Morgoth. If there indeed were such fixed ways then it could have also spared a lot of effort in getting back to Aman; you would only need a couple of trusty men who would make sure to relay your help-requesting message. Also, the wars fought in the Hither Lands would have been greatly reduced in number thus preventing a lot of tragedies due to the Valar not giving a care about the plight of the Noldor and the free folk of Beleriand, save for the few times when the Valar had interfered. Although most of those were the works of Ulmo alone…

In The Silmarillion, we can read that Manwë had sent Thorondor to Fingon’s aid when he prayed to him so that he could free Maedhros from the peak of Thangorodrim:

Thus Fingon found what he sought. For suddenly above him far and faint his song was taken up, and a voice answering called to him. Maedhros it was that sang amid his torment. But Fingon climbed to the foot of the precipice where his kinsman hung, and then could go no further; and he wept when he saw the cruel device of Morgoth. Maedhros therefore, being in anguish without hope, begged Fingon to shoot him with his bow; and Fingon strung an arrow, and bent his bow. And seeing no better hope he cried to Manwë, saying: ‘O King to whom all birds are dear, speed now this feathered shaft, and recall some pity for the Noldor in their need!’ His prayer was answered swiftly. For Manwë to whom all birds are dear, and to whom they bring news upon Taniquetil from Middle-earth, had sent forth the race of Eagles, commanding them to dwell in the crags of the North, and to keep watch upon Morgoth; for Manwë still had pity for the exiled Elves. And the Eagles brought news of much that passed in those days to the sad ears of Manwë. — Quenta Silmarillion, Of the Return of the Noldor

It is clear from the text that the great eagles always brought tidings about the Hither Lands to Manwë so he was quite aware of what happened to the elves residing there. However, there is no mention of Manwë giving instructions on what should be done about Morgoth, so the eagles constantly informing him was a one-way communication only. If Manwë was so sad, then why did he not do anything about his waylaid brother who terrorized the beings he was so sad for?

There were two other occasions when a Vala actively helped the elves in Beleriand but both of those were the deeds of Ulmo, Lord of the Waters. First, he saved an elf from drowning. That elf was Voronwë who was amongst the delegation sent by King Turgon to find a way to Valinor and beg the Valar for their forgiveness so that the Noldor can go back to Aman. They did not succeed, and, in the end, only Voronwë survived thanks to Ulmo, who also entrusted him to show Tuor the way back to Gondolin so that they could warn the Gondolindrim that their city would be discovered by the Enemy and they should leave it.

By the way, it was also Ulmo who revealed the hidden valley of Tumladen to Turgon where he later built Gondolin. And it was Ulmo again who showed Finrod the abandoned cave of Nulukkizdîn which later became the capital of the realm of Nargothrond. Later, Ulmo cautioned the people of Nargothrond to destroy their bridge built by Túrin and close their doors as his powers were withdrawn from the Sirion so he was unable to protect them any longer. This was also the reason why he sent a message to Gondolin as well, by the way. Neither the Gondolindrim nor the elves of Nargothrond heeded his warnings and that decision led to their ruin…

Elrond’s mother, Elwing was saved due to Ulmo’s powers as well. So, it should be obvious that amongst the Valar, Ulmo was the most supportive and considerate towards the elves in Beleriand. Aside from these mentioned occurrences, the Powers of Arda had not deigned to do anyone a favour until the War of Wrath. But even before that, they needed to have someone to beg for it. We already know that Manwë was very much aware of the happenings in Beleriand as the eagles always brought him news about those and yet despite being the appointed High King of Arda, he needed someone to spell out for him that there are severe problems outside Aman. He also held back Oromë and Tulkas, Valar who wished to do something about Morgoth when he destroyed Laurelin and Telperion.

Putting that aside there indeed is an allusion to the running communications between the two continents in The Silmarillion, but there is no indication of any kind of trade though. Here is the part I am talking about:

But new tidings were at hand, which none in Middle-earth had foreseen, neither Morgoth in his pits nor Melian in Menegroth; for no news came out of Aman whether by messenger, or by spirit, or by vision in dream, after the death of the Trees. In this same time Fëanor came over the Sea in the white ships of the Teleri and landed in the Firth of Drengist, and there burned the ships at Losgar. — Quenta Silmarillion, Of the Sindar

So, there was communication, but these connections were confidential and were most certainly not used to help people, save from those the receiver deemed important enough to inform. It is evident that the Ainur had several means of long-range communication despite the distance between Middle-earth and the Blessed Realm. Melian probably told Thingol what she discovered as she endeavoured to preserve Doriath to the best of her knowledge, but the Nandor who sought their protection were not given much regard unless they settled down within the Girdle of Melian. Only those within the borders of Doriath were given priority and similarly to them, any other leader in Beleriand did the same: the safety of their own people took precedence over the safety of allies. For example, Turgon was so concerned about the Gondolindrim’s survival that his worries practically clouded his judgement, especially after the Nirnaeth Arnoediad where he became the last child of Fingolfin remaining. Likewise, the Feanorians’ primary goal was both the retaking of the Silmarilli and the well-being of their people who loyally fought by their side. So, in a nutshell, the tidings that any ruler got from Aman did not circulate between Belerandian allies even if the ruler in question took up arms to aid those allies in battle, thus reinforcing my third and fourth points.

6) During the wars, but even before them, in the Years of the Trees, Sindar, Nandor, Teleri and Avari elves had died fighting the dark forces who were commanded by Sauron in his lord’s absence after Morgoth himself was imprisoned in the Halls of Mandos. We also know that the souls of elves who die are housed in these very Halls and await their re-embodiment. If there indeed was trade and communication between the Hither Lands and the Blessed Realm and if those dead non-Valinorean elves were re-embodied, they would have come to live near the Noldor, the Teleri and the Vanyar, because they would have been already familiar with them. If that had been the case, I believe that the detail-oriented Tolkien would have mentioned something like this even in something as unfinished as The Silmarillion but nothing of the sort is ever noted.

So, if those elves were re-embodied and lived in Aman, then they most certainly did not dwell near the already existing elven cities. But if they knew the Valinoreans, why would they do that? If there were indeed Sindar in Aman, then gradually and still in the Years of the Trees, Sindarin would have become another spoken dialect and would have created a need amongst the Quenya-speaking dwellers to learn the language, and perhaps it would have prompted the Valinoreans to take Sindarin lessons. This would have rendered the need for the Noldor and Sindar to learn each other languages when the Finweans met them. The initial language barrier, however, is actually quite plainly written in The Silmarillion.

Now in Mithrim there dwelt Grey-elves, folk of Beleriand that had wandered north over the mountains, and the Noldor met them with gladness, as kinsfolk long sundered; but speech at first was not easy between them, for in their long severance the tongues of the Calaquendi in Valinor and of the Moriquendi in Beleriand had drawn far apart. From the Elves of Mithrim the Noldor learned of the power of Elu Thingol, King in Doriath, and the girdle of enchantment that fenced his realm; and tidings of these great deeds in the north came south to Menegroth, and to the havens of Brithombar and Eglarest. Then all the Elves of Beleriand were filled with wonder and with hope at the coming of their mighty kindred, who thus returned unlocked-for from the West in the very hour of their need, believing indeed at first that they came as emissaries of the Valar to deliver them. — Quenta Silmarillion, Of the return of the Noldor

This also explains what I referred to right above the first point, and the part I highlighted proves both my first and second points as well.

I hope these six points at least somewhat show you why I think that the paragraph (from the essay) quoted above is a complete bullock, and after this point, it does not get better. As I have already hinted, this essay is almost the complete opposite of the article Elven naming tradition of Valinor in precision.

But would there be any naming traditions that they didn’t already have? From a linguistic point of view, there is a striking similarity to the Sindarin word “eneth” and the Quenya word “anesse”, suggesting that the Úmanyar also have Given-names. Denethor (which originally was a Common Eldarin name, “Denitháró – Lithe and Lank”) is obviously an Epesse, given to the hero who saved the Nandor. Another example of an Epesse given before the languages had truly split is Elwê’s name, “Thindikollo – Grey Cloak.” It refers to his silver hair.

The question and the following sentence are all right though the accents on every single Elvish moniker and on the word anessë are wrong. Also, Denethor is the name of a Nandorin elf and the Nandor were counted as both Moriquendi and Úmanyar whereas the Eldar came from Aman, therefore Common Eldarin could not be possibly spoken by any elf who never went to the Blessed realms in their life. And, the Primitive Elvish form of Denethor was Denethara not Denitháró, assuming that the essay’s writer indeed meant Primitive Elvish by ‘Common Eldarin’. This error is followed by the misspelling of the word epessë twice in a row and then writing wrongly both Elwë’s name and his after-name since the proper Primitive Elvish form of his epessë is Thindigollo. The writer mayhap confused it with its archaic Quenya form, Þindikollo. What this nickname actually referred to I will not argue about, because theirs is as good a guess as any.

The Parentless Elves (the Elves who first awoke on the shores of Cuiviénen and who therefore have neither parents nor a birth at all) all have Chosen-Names. While the Noldor glorified and enshrined this quite a bit, we don’t know to what extent the other cultures developed this; we can guess that they also could choose their own names, like their fore-fathers did. Also, there may be the odd occasion wherein an Elf decides to leave their old names behind, and go by an Alias, so that type of Chosen-name we can’t rule out either. There is little in the way of evidence of Mother-Names, but it seems unlikely that they wouldn’t also exist, as any Elven woman is capable of having insight in the hour of birth into her child’s future life and personality. Therefore, I contend that Mother-names are also possible.

What these paragraphs describe, I can agree with, only I would add that if the Úmanyar elves naming conventions were so similar to those coming from Valinor then Tolkien would have mentioned it in any of his writings left behind and thus we, fans, too would be more certain concerning this.

Finally, the Father-Name. We know that in an earlier version, of his Elven language history, Tolkien made a way to have Father-names for the Ilkorin Elves (uncivilized Elves outside the Elven cities) from a note in the Etymologies. They have a different sort of Fathername, which is completely unlike the Quenya or Sindarin Fathernames, wherein “go-” is prefixed onto a parent’s name. Also, this sort of name is just convenient.

The essay’s writer knew about Ilkorin so they should be also aware that J. R. R. Tolkien had phases in which he evolved the elvish dialects. For those who are not aware, Tolkien polished his fantasy languages through three phases: there was an early (1910-1930), a middle (1930-1950) and a late period (1950-1973) and Eldamo.org (https://eldamo.org/index.html) is a splendid site for etymology freaks not unlike myself. If you open the website you will see in the Language Index that Ilkorin (or Doriathrin) is an elvish dialect in the Middle Period.

What my problem is, if the article’s writer was aware of the Ilkorin elves then they should also know about these Periods and then they should also know that Tolkien, as a linguist, was very detail-oriented. Not mentioning that go- was the Gnomish prefix for patronyms and exclusively meant ‘son of’; not ‘not daughter of’ not ‘child of’, but its explicitly written down that go- stood for ‘son of’. In Ilkorin, it was simply go (‘from, away; patronymic’) and Tolkien demonstrated its use in the phrase Luithien go Thingol which translates into ‘Luithien, child of Thingol’. (By the way, Luithien is a variation of Lúthien.)

Also, a patronymic is not the same as a father-name neither in principle or practice. While a father-name could, and in most cases of the Eldar did, contain an element from either parent name, in Tolkien’s world, a patronymic was constructed by swapping -ion or -iel after the parent’s name. For example, Gildor Inglorion (“Gildor, son of Inglor”), Aragorn Arathornion (“Aragorn, son of Arathorn”), Arwen Elrenniel (“Arwen, daughter of Elrond”) and, in the first Peter Jackson movie, there was Legolas Thranduilion (Legolas, son of Thranduil).

“ In conclusion, I believe that the naming traditions of the Eldar come from the shores of Cuiviénen, and therefore aren’t completely different amongst the sundered Elves. That being said, I believe that the Úmanyar’s names are structured like this:

Indeed, the Eldarin naming conventions must have come from the shores of Cuiviénen, but since the writer already confused the Eldar and the Dark Elves once, I believe they meant the elves staying behind in the Hither Lands. And I have already mentioned this a bit more above, but for clarity’s sake: if the Úmanyar’s naming traditions were similar to the Exiles’ own, Tolkien would have mentioned it either in The Silmarillion or one of the Appendixes.

1. The first name is a Father name, with some portion of the father or mother’s name in it, and probably ending in -ien, -iel, or -ion. There probably would be some sort of ceremony or celebration for the parents to show off their new child, and let everyone know of its existence, wherein they would also tell everyone their new baby’s name. This name probably had very little personal significance, and could be used by outsiders.

What they wrote I have never ever seen in amongst Sindarin names. (On Eldamo you will find the whole list of names Tolkien has ever committed to paper.) But the patronymics sure can be used by anybody to address other elves, though I imagine that would be similar to how we address people by their surnames.

2. The second name describes the Elf’s personality. It is chosen later in life, when the Elf’s personality has taken form. For the Úmanyar, gaining linguistic ability and intelligence isn’t as highly prized as it is for the Noldor, so there probably isn’t a Name-Choosing ceremony amongst the Úmanyar. I do think that there can be more than one of these names, possibly one given by the mother, using her unique insight into her child’s personality and future. This name probably was much more intimate and personal for the Elf who had it, so using it would require a personal relationship. It would be rude for outsiders to use this name.

I reckon it would be more precise to say the name somehow does describe the elf, but one would indeed have to get to know him or her better for that. As I said above, I do not believe that there would be any equivalent to ataressë or amilessë amongst the Úmanyar, and as the essay’s writer noted the Úmanyar did not prize linguistics as much as the Valinorean elves did. I think it is more probable that a child’s parents together chose a name they thought would befit them, but anyone could address them by that if they knew it.

3. The third name is an Epesse of some sort, or a professional’s title. It can be descriptive of some event the Elf is well known for, the place that such an event took place, or some outstanding physical or mental feature that the Elf is well known for. Other than titles of nobility, Tolkien wrote about two professional titles: Celebrimbor for silver smiths and Tegilbor for scribes. So we can infer that people were sometimes referred to by their occupation instead of their name. ”

Again, I feel I need to specify the things written better. What I concluded from the name list on Eldamo, an epessë can become a professional title and vice-versa a professional title can become an epessë. For example, there is the Telerin Nówë who is mostly known by his epessë, Círdan which consists of the word círdan (‘shipwright, shipbuilder’) and it is simply an occupation used as a moniker; he was probably the most excellent in this craft or he might have been the one who founded it. The same might be the case with Tegilbor.

Celebrimbor is a bit of a complicated case… If we take The Silmarillion as canon then he was a Noldo, but in other texts, he was either a Teler or a Sinda or his lineage is not specified at all. Within the stub Concerning Galadriel and Celeborn in the chapter The History of Galadriel and Celeborn in the Unfinished Tales (c. 1959), there is a mention about the Noldo Celebrimbor that he wished for his skill and fame to rival Fëanor’s own. I think an ambitious person like that would prefer if it would be his personal name to become renowned and not an occupational title made into epessë. In a text called Eldarin Hands, Fingers and Numerals from c. 1968, Celebrimbor is a Telerin elf who accompanied Celeborn into his exile to Middle-earth and according to this text, Celebrimbor was indeed an epithet for famous silver-smiths amongst the Teleri. However, in a later text titled as Of Dwarves and Men from c. 1969, Celebrimbor is depicted as a Sinda and son of the minstrel Daeron. As I have already cleared that a professional title can become epessë then it is very probable that his real name was something else but he was so outstanding in silver-smithing that he was just referred to as Celebrimbor. (In this point I had worked hard to deliberately put aside my own preference of a Fëanorian Noldo Celebrimbror because I am such a big simp for the Fëanorians! So, I suppose it is not surprising that I am glad that in the latest known versions of The Silmarillion he was made to be Curufin’s son and this will always remain my canon too!)

General Facts About Elven Names in Middle-earth • Since the Elves of Middle-earth are so spread out, it’s unlikely that everyone could know what everyone’s names are, and if they ended up with the same name, they wouldn’t know it. Even so, they don’t take names they know are being used by someone else. To do so would create confusion. So, the names of famous historical figures wouldn’t be taken as chosen names, and I doubt an Elven mother would give their child the name of someone famous. Using someone else’s name is considered trying to impersonate them. There is no Elven equivalent to “John Smith”.

This is a very valid point and there is nothing wrong with it, plus I 100% agree with it.

• Elves don’t share their Father-names when they marry. Their names are unchanged, except for the romantic nicknames they call each other.

Although the writer confuses patronymic and father-name again, what they say is yet again correct. A famous example of this is Galadriel; her ataressë was Artanis (“Noble Woman”) and her amilessë was Nerwen (“Man-maiden”) whereas the moniker Galadriel was an epessë bestowed by Celeborn, but since she found this the most beautiful amongst her epessi it became her chosen name.

• Elves’ names change as the language around them changes. This is also why Legolas is sometimes called “Greenleaf.” It is simply the translation of his name into Westron, not a surname.

This also might seem appropriate even though I do not agree with it. Let’s use Legolas’ name again as an example: it is indeed translated as “Greenleaf” but it is a Nandorin and not a Sindarin name so the proper Sindarin moniker would be Laegolas. However, the Sindarin word laeg (“fresh and green, viridis, green (of leaves/herbiage”) was, by the Third Age, already an archaic one replaced by calen (“green; fresh, vigorous; †bright”). So, due to this example, I suppose it becomes a bit more understandable why I do not completely agree with it, but let me give another instance using Elrond’s name. The nomen uses the Sindarin elements êl (“star”) and rond (“(vaulted or arched) roof; vaulted chamber or cavern; heavens [as a roof of the world]”). By the third Age êl, just like laeg, became an archaic word and gil (“star; (bright) spark, silver glint, twinkle of light”) replaced it in speech. Therefore, if the statement is wholly true then Elrond would call himself Gilrond in the Third Age, just as Legolas would rather use Calenlas, because the first elements of their names became archaic and fell out of common use. This reasoning just sounds stupid, isn’t it? Well, this is what the writer apparently says. An elf’s name does not change if the bearer themselves do not wish to change it. Plus, if the names would also change with the language then that means they would also change in the written chronicles and if you are not a linguist this would be plainly confusing. Like, they would refer to Elu Thingol as Gilu Thingol and you would not know that Elu and Gilu describe the same person unless you are a loremaster. Fortunately, this is not so; the writer’s statement is true to the degree that a word corresponding to the linguistics of the age would more likely be used as a name element, but I say that is not always the case, Legolas is a good example of this. Also, Greenleaf was also used along with his given name (like ‘Legolas Greenleaf’) and never alone.

• Elves never use the names of Eru, the Valar, or Maiar as their own. It’s considered trying to become or impersonate a god. Similarly, they aren’t named abstract concepts like “Justice, Mercy, Love, Victory, Life, Death” or the names of countries or natural things like “Star, River, Fire, Earth, Sea”. Names referencing these things usually indicate the person’s relationship with them, like Gaerdil (sea-lover) or Edennil (human-lover). Names about one’s ethnicity or homeland are usually indirect references, like Legolas (green-leaf), which references his homeland (Mirkwood is called the “forest of green-leaf” in Sindarin) and his ethnicity as a Legel (green-elf). A name referencing something like stars or rivers and so on wouldn’t just be “Star” or “River”, but would be compound name, showing in what way the character is like the thing, like “Thranduil” (vigorous-river) who has a river running through his home. The name is suggesting that he’s energetic and strong as this river. Barring Ataressi, names are usually descriptive of the elf, often just an adjective with a name suffix added or a description of a specific characteristic. So, names like Arwen (noble maiden) or Glorfindel (golden-hair) are the most common.

I agree with this point utterly, only there are a few inaccuracies concerning the brought-up examples. Legolas was not a ‘Legel’, he was a Sinda or Grey elf, though that does not mean he cannot be a Laegel –as the Sindar referred to a Green elf–, however, the elves who dwelt in both Lothlórien and Mirkwood were called the collective term Tawarwaith (“Forest People”). Even though they indeed descended from the Green Elves they were referred to as Silvan Elves by the Third Age. Also, the moniker Thranduil means “Vigorous Spring” and it contains the Sindar adjective tharan (“vigorous”) and the noun tuil (“spring” as in the season). Regarding Arwen’s ordinariness as a name, well it is indeed a simply constructed nomen so it is indeed highly possible that there might have be other Arwen out there in Middle-earth, but no other Arwen had the after-name Undómiel (“Evenstar”) as this was only beared by the daughter of Elrond. Moreover, this was a Quenya epessë and thus was very unique in the Third Age where Sindarin was the Middle-earth-wide spoken language whereas Quenya was in position as Latin is in our world and current age. And concerning Glorfindel, its wearer was originally a Noldo from Valinor and the Noldor usually have dark hair, so one who was born with golden blond tresses counted as extraordinary and was unusual in Middle-earth too, especially by the Third Age when the other (mentioned) golden-haired elf is Thranduil, and this could not be more canon as it is since Tolkien himself wrote it. Galadriel got her name due to her luxurious gold-silver hairlocks as it was highly unusual, to say the least; it was quite a big deal for elves to see such hair colour. So, it was not likely to encounter another Glorfindel in Middle-earth as he was a well-known figure by the Third Age when most of the elven population had dark hair with the occasional silver in Telerin bloodlines like Celebrían and Celeborn.

And finally, I would like to give my own observations about elvish names in Tolkien’s universe also serving as an extension to the last point above. Since I mentioned the Third Age and Sindarin so much, let us begin with the Grey Elven names. I will discuss both genuine Sindarin names and Sindarinized Noldorin names, though I will write the equivalents of Quenya and Sindarin suffixes, if there are such, in parentheses. Also, an asterisk* behind a nomen will be marked as (known) epessi while the names translated from the other dialect will be underlined.

Generally used feminine suffixes in Sindarin:

-dis (Q -nis) ‘female agent’ or ‘bride’

-eth (Q -issë) ‘feminine ending’

-iel (Q -iel) ‘daughter; feminine suffix’

-ien (Q -ien) ‘feminine ending’

-il, -el (Q -iel) ‘feminine suffix’

-wen (Q -wen) ‘maiden, feminine suffix’

In the Sindarin utilized by elves -iel specifically never appears as part of the elf’s chosen name only when it is used in an epithet or patronymic. See Ar-Feiniel, Elrenniel, Gilthoniel, Tinúviel for instance, all of them function as an epessë would and are not the actual name of the person in question as Gilthoniel was an appellation of Varda in Sindarin. However, -iel and its variants in Mannish Sindarin were more likely to be used in given names than the suffix would have been in Elvish names. See Berúthiel, Fíriel, Ivriniel, Lothiriel and Niniel for example.

Female Elvish names: Aredhel, Ar-Feiniel*, Arwen, Astoreth, Celebrían, Celebrindal* (Q Tyeleptalëa), Edhellos, Elrenniel*, Elwing, Faelivrin*, Finduilas, Galadriel*, Gilmith, Gilthoniel*, Gladhwen, Idril, Íreth, Laewen, Lindis, Lúthien, Melian, Mithrellas, Nellas, Nimloth, Nimrodel, Rodwen, Tinúviel*

Female Mannish names: Adanel, Andreth, Berúthiel, Eledhwen*, Emeldir, Finduilas, Fíriel, Galadwen, Gilraen, Glóredhel, Ioreth, Ivorwen, Ivriniel, Lalaith, Lothiriel, Meldis, Morwen, Niniel, Rían, Saelind*, Urwen

Generally used masculine suffixes in Sinadrin:

-bor (Q -quar) ‘fist’

-dil, -nil (Q -(n)dil) ‘friend, lover’

-dir, -nir (Q -ner) ‘man’ as in the sense of ‘male person’

-dor (Q -tur) ‘king, lord’

-hir ‘lord’

-ion (Q -ion) ‘son’

-on (Q -ndo) ‘masculine suffix’

-or ‘agental suffix’

-(r )on ‘agental suffix’

-u (Q -wë) ‘a person or being’

Masculine names are a bit more trickier. Male elves, or all elves in general, are more likely to use compound names that are built up of words inspired by the physical world, especially by nature. See Celeborn, Legolas, Malgalad, Oropher, Saeros, and Thranduil for example. The suffix -u was used only once in Elu’s (“Star Person”) moniker in The Silmarillion. Meanwhile, the usage of -ion is mostly limited to after-names and patronymics. The other suffixes are common in both Elvish and Mannish names be they given names or epessi but perhaps the Men had tended to prefer -dil/-nil, -dir/-nir, -dor and -hir a little better than the Elves did. However, these are merely my own musings as the Sindarin name list on Edalmo contains literally all the names including place names, epessi, weapon and animal names as well, though Mannish names are the majority of personal names in the list. Here, however, I will be focusing on the names of people.

Male Elvish names: Aegnor (or Goenor), Aerandir, Amras, Amrod, Amroth, Angrod, Annael, Aramund, Aranel*, Arminas, Arothir, Astoron, Beleg, Bronwe, Caranthir, Celeborn, Celebrimbor, Círdan*, Curufin, Cúthalion*, Daeron, Denethor, Dior, Duilin, Ecthelion, Edennil* Edrahil, Egalmoth, Elladan, Elrohir, Elrond, Elros, Elu, Eluchíl*, Eluréd, Elurín, Enerdhil, Ereinion*, Erellont, Erestor, Ergammon, Faenor (or Fëanor), Falathar, Felagon*, Felagund*, Finarfin, Findor, Finellach*, Fingolfin, Fingon, Finrod, Fin (or Finu), Finwain*, Firindil*, Gaerdil, Galadhon, Galdor, Gelennil, Gelmir, Gildor, Gil-galad, Glindúr, Guilin, Gwindor, Haldir, Inglor, Legolas (or Laegolas), Lindir, Mablung, Maedhros*, Maeglin, Maglor, Ornil, Oropher, Orophin, Pengologh, Peredhel*, Rasmund, Rodnor*, Rúmil, Tarmund, Tegilbor, Thingol*, Thinrod, Thranduil

Male Mannish names: Adanedhel*, Agarwaen*, Amlaith, Amrothos, Anborn, Angbor, Aradan, Arador, Araglas, Aragorn, Aragost, Arahad, Arahael, Aranarth, Aranuir, Araphant, Araphor, Arassuil, Arathorn, Araval, Aravir, Aravorn, Argeleb, Argonui, Arvedui, Arvegil, Arveleg, Baragund, Barahir, Baranor, Baravorn, Belecthor, Beregar, Beregond, Beren, Bergil, Bór, Borlach, Borlad, Borlas, Boromir, Borondir, Borthand, Brandir, Bregolas, Camlost*, Celebrindor, Cirion, Dagnir, Dairuin, Damrod, Denethor, Derufin, Dervorin, Dírhael, Duilin, Duinhir, Edelharn*, Egalmoth, Eladar, Ecthelion, Elphir, Eradan, Erchamion*, Erchirion, Estel*, Faramir, Findegil, Fuinur, Galdor, Galador, Gilbarad, Gildor, Glirhuin, Glórindol, Gorthol*, Gundor, Hador, Halbarad, Haldir, Hallas, Handir, Hathhaldir, Hathol, Henderch, Herion, Hirgon, Hirluin, Húrin, Iorlas, Labadal, Malbeth, Mallor, Malvegil, Mormegil*, Naeramarth*, Neithan*, Orchaldor, Radhruin, Ragnir, Ragnor, Sador, Saelon, Targon, Telchandir*,Thalion, Thorondir, Thorongil*, Thurin*, Thuringud, Turamarth, Túrin, Udalraph*, Uldor, Ulfang, Ulfast, Ulwarth, Úmarth*, Urthel

Generally used feminine suffixes in Quenya:

-ë female names often end in this

-ië another usual feminine ending

-iel (S -iel,-il,-el) ‘-daughter; feminine suffix’ also ‘feminine patronymic’

-ien (S -ien) ‘feminine ending; feminine patronymic, -daughter’

-issë (S -eth) ‘ending in feminine names’

-ldë ‘feminine agent’

-llë ‘feminine agent’

-ndë ‘feminine agent’

-nis (S -dis) ‘woman’ as in ‘female person’

-wen (S -wen) it is the suffix form of the archaic version of vendë, meaning ‘maiden’

Like the Sindar and with the sole exception of Míriel (Fëanor’s mother), Quenya-speaker elves do not use -iel in their cilmessi neither they have it in their ataressi or amilessi. However, it is heavily used in the case of epessi and when they refer to a female by their parent –usually the father– in the form of patronymics. Just like the Men of Middle-earth, Númenóreans and later also the Men of Númenórean descent, prefer to utilize -iel, -ien and their variants in their nomina than any other alternatives mentioned above. See Ailinel, Almarian, Almiel, Míriel (also known as Ar-Zimraphel), Silmarien, Telperien, Tindómiel, and Yávien. Also, the Númenórean were more prone to use the Valar’s name in their own: Nessanië, Uinéniel, Vardilmë.

Female Elvish compound names: Amarië, Anairë, Artanis, Eärwen, Eldalótë, Elenwë, Findis, Ilwen, Indis, Írimë, Írissë, Itarillë, Lalwendë, Míriel, Nerdanel, Nerwen, Serindë*, Tyeleptalëa*, Undómiel*

Female Mannish compound names: Ailinel, Almarian, Almiel, Ancalimë, Elestírnë, Erendis, Írildë, Isilmë, Lindissë, Lindórië, Mairen, Míriel, Nessanië, Silmarien, Telperien, Tindómiel, Unéniel, Vanimeldë, Vardilmë, Yávien

Generally used masculine suffixes in Quenya:

-ion (S -ion) ‘-son, masculine patronymic’

-mo ‘agental suffix’

-(n)dil Variants: -dil, -nil, -ndil (S -dil, -nil) ‘-friend, -lover; devotion, disinterested love’

-(n)dur Variants: -dur, -nur, -ndur ‘servant; to serve’

-ndo (S -on) ‘masculine agent’

-r(o) Variants: -r, -ro ‘agental suffix’

-wë (S -u) ‘ancient name suffix (usually but not always masculine)’

Similarly to the cases above, Elves are more likely to use compound names that may contain one of the mentioned suffixes, particularly in their epessi, whereas Men, especially the Númenóreans, usually stick with -ion, -(n)dil and -(n)dur. The following instances are all from Eldamo’s Quenya name list and I deliberately wrote down every moniker worn by Men and elves related to this matter so my point will be seen. Also, with the exception of Lómion which is Maeglin’s amilessë, and the only instance in Quenya when -ion is used in a mother-name, all the other nomina utilizing -ion is a patronymic. Urundil is the epessë of Mahtan who is Nerdanel’s father and thus Fëanor’s father-in-law and Eärendil was actually ‘just’ half-elven so his name is also listed below as well. Aulendur however is more of a title for Noldor who entered into the service of the Vala Aulë rather than it is an actual personal name. As opposed to the Elvish names, the Men were a bit less squeamish to use a Vala’s name in their own.

Male Elvish names: Aicanáro, Ambaráto, Ambarto, Ambarussa, Angamaitë, Angaráto, Aracáno, Arafinwë, Aranwë, Aranwion*, Artafindë, Artanáro*, Artaresto, Atarincë, Atyarussa, Aulendur*, Canafinwë, Carnistir, Ciryatan*, Curufinwë, Eärendil, Elemmacil, Elerondo, Elerossë, Elmo, Elwë, Fëanáro, Findaráto, Findecáno, Finwë, Finwion*, Ingalaurë, Ingoldo, Ingwë, Ingwion*, Laicolassë, Laurefindelë, Lenwë, Lómion, Macalaurë, Mahtan, Maitimo, Minyarussa, Minyon*, Morifinwë, Morwë, Nelyafinwë, Nolofinwë, Nurwë, Olwë, Pityafinwë, Quengoldo, Russandol, Sarafinwë, Sarmo, Sindicollo*, Telperinquar, Telufinwë, Tyelcormo, Turucáno, Umbarto, Urundil*, Voronwë

Male Mannish compound names: Aldamir, Aldarion, Amandil, Anardil, Anárion, Ancalimon, Anducal, Aracorno, Arantar, Arciryas, Ardamin, Ardamir, Artamir, Atanalcar, Atanamir, Aulendil, Axantur, Calimehtar, Calimmacil, Calion, Caliondo, Calmacil, Castamir, Cemendur, Ciryaher, Ciryandil, Ciryatur, Ciryon, Eärendil, Eärendur, Eärnil, Eärnur, Elatan, Elendil, Elendur, Eldacar, Eldarion, Elentirmo, Elessar*, Envinyatar*, Estelmo, Falassion, Falastur, Hallacar, Hallatan, Herucalmo, Herumor, Herunúmen, Hostamir, Hyarmendacil, Írimon, Isildur, Isilmo, Malantur, Mámandil, Manwendil, Mardil, Meneldil, Meneldur,Minalcar, Minardil, Minastan, Minastir, Minohtar, Minyatur, Narmacil, Nolondil, Nólimon, Númellótë, Númendil, Ohtar, Ondoher, Ornendil, Oromendil, Orontor, Ostoher, Palantir, Parmaitë, Pelendur, Quennar, Rómendacil, Siriondil, Súrion, Tarannon, Tarciryan, Tarondor, Tarostar, Telcontar, Telemmaitë, Telemnar, Turambar, Ulmondil, Umbardacil, Úner, Valacar, Valandil, Valandur, Vardamir, Vëantur, Vinyarion, Vorondil

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Have same foxes.

So, yes, I'm still alive. A lot of things have happened and in the last two years, especially this last year, I've faced a massive art block. In 2021 there were so many things I wanted to show that I ended up not posting a single thing, and in 2022 my mother died during the pandemic. Ironically enough it was not COVID that killed her; it was cancer, but it is even more likely that the chemotherapy itself was her undoing in the final stages of her life.

The cancer was a quintuple metastasis one, starting from the liver, but in the beginning, things didn't seem so dire. A little more than half of her liver had to be removed via surgery; originally the hospital didn't want to let the doctor do it, saying "It's too risky for him", but the doctor responded that "he alone will decide what is too risky for him". This was just a little part of my mother losing her fight for life. Things somehow deteriorated quickly. With her death, a whole sh*tton of problems were unleashed upon my brother and me; quarrels about the inheritance with our maternal grandfather, disputes with mother's friends, and I could just watch as the family was falling to pieces. Even my brother and I began to become distant, and it was just horrific...

Well, fortunately, this is all in the past now, and I got my brother back. :) The maternal branch of the family not so much, but I don't really mind that as my relationship was never such a splendid one with them. I'm sure it was like a surprise for them because, on that part of the family, we could never properly discuss things on the emotional side, so me relaying my feelings to them was quite nonexistent altogether. That is if we don't count the occasional outbursts on my part, which were met with equal vehemence, but never with understanding.

So, these are my kitsune OCs, the silver fox is the father and the other is his son. The silver fox is called Soutenmaru (宗典丸, "law of essence"), but later he is just known as Kyoushi (佼志, I won't translate this 'cause there are too many possibilities) and the ash brown haired one is named Souma (颯磨, "quick to improve").

They were characters from my original story 'The Giddy Fox and the Reticent Blossom' written in Hungarian, my mother language. It's about the romance of a kitsune and a human woman; Souma and the woman meet due to the kitsune making a bet with his teacher, Kyoushi. Souma was Kyoushi's best apprentice and feeling ready to prove this, he wanted to distinguish himself. Kyoushi, on the other hand, opposed this idea, but then they eventually wagered: if Souma is able to seduce the younger twin of the Tougou brothers, then he earns the right to do as he pleases, but should he fail, Souma will have to study even harder under Kyoushy extended tutelage without a complaint. The plot twist is that this mentioned younger twin brother is actually female(!) who, due to some circumstances unknown even to her, was raised as a man. I suppose it's obvious that in these settings it's only natural that drama ensues...

Here are the twins:

Do they look like characters from Hakuouki? I bet they do, since the time I drew these I was pretty much into Kazuki Yone's style, the one artist who designed Hakuouki's characters.

The girl is called Kazusa (冬桜, "winter cherry"), but initially is introduced as Kojiro (子白, "child of white"). Her older brother is named Kazushiro (冬白, "wintry white"). Although he laughs freely, he is also angered more quickly, but despite this, he prefers to be around people. Kazusa is just the opposite: she is quiet by nature and rather would be alone. Her smiles are usually displayed because of politeness, nevertheless, she has way more tack when it comes to dealing with people.

When I first began to flesh out Soutenmaru, he was part of my InuYasha fanon. He was the young Sesshoumaru's teacher and his original design was very different. He wasn't even a fox, but a youkai of youthful appearance who was just known as the 'Genji amongst youkai'!

Okay, perhaps not so different from the current Soutenmaru. Oh, and look! A cute, little Sesshoumaru. By the way, these are from 2012. I think this will be enough for now...

0 notes

Photo

Pictures and references for my Silmarillion & LoTR fanfic, Gwatha i Dû. New batch can be found here.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Dísa attacks again

Other than messing with and pissing people off, another hobby of Dísa's is to dress up as a guy. In this guise she is polite and charming, especially to the ladies though she's generally more courteous. This guise is more like a tribute to the memory of her dead twin brother, Ríki, since she had significant role in his demise. After Ríki's death Dísa became emotionally unstable a bit; more quick to be angered, physically lashing out at others, developed a tendency for sadism and cruelty etc.

All in all she became a darker version of herself, and with that she also developed the habit of having many aliases. When she's with her father she is Freydís Geilir, with her mother she is either Yagami Suki (弥神 主貴) or Kagebira Kazuki (欠平 火月生), though she hates being called as Suki but the name was given by her mother so it's used nonetheless. When she wishes to have the company of the ladies, she's Yuu (酉), but she has more pseudonyms, and her favourite ones include Tsubakura (燕) and Yuuka (夕花) too.

This is another example of Dísa’s craze of disguising herself as a male. Her breast really cannot be seen because she binds them. On top of that a big number of woman hearts have fallen for her since Kazuki is just as good at lying and pretending as Seka (one of her maternal ancestors who is famous for ruling the clan for hundreds of years). And if we're already at it -though you might have a suspicion, for it was already mentioned-, I can tell you that Dísa has a certain portion of, khmm... bisexuality.

Dísa in her distinctive attire as a girl with her her many-times-mentioned dead twin brother, Ríki who is older than her with sixteen minutes and forty-nine seconds. Dísa often called herself a realist and Ríki a dreamer because of his gentler nature. Well, this doesn't mean that he has the temper of a newborn lamb, he merely has a milder personality than her. (As I mentioned it in my fisrt post about Dísa.)

Ríki’s full name is Freyríkr Geilir though in their mother's home he is referred either as Yagami Suhai (弥神 主伾) or Kagebira Hibiki (欠平 飛火崎), but he still own a third nickname wich is Yuuki (夕毅). Otherwise he is addressed as Ríki, mostly by Dísa and their paternal family.

Dísa appearing as completely human, then in her markless demonic form, and some early concepts about her marks. As I told it before in the first post about her, Dísa (thus Ríki too) is a half fire-demon due to her father, Solarr Geilir (Just Sol to his close friends) who is a pure-blooded fire-demon from Múspellsheimr. Due to her mother she is one-sixth demon (of unknown origin), one-sixth deity and one-sixth human. Because of this, Dísa often says about herself that she is ‘more of a demon than human’. There is nothing wrong with the statement itself, the problem is that Dísa frequently uses this as an excuse for violence. Also Dísa is quite proud of her pedigree despite of her illegitimate birth and she doesn't hesitate to flaunt both in front of people, mostly to either appal or frighten others. She just likes laughing at others' expression.

#ildebrann#multiple names alert#detailed explanation alert#my ocs#dísa#illustration#concept art#sketches

0 notes

Photo

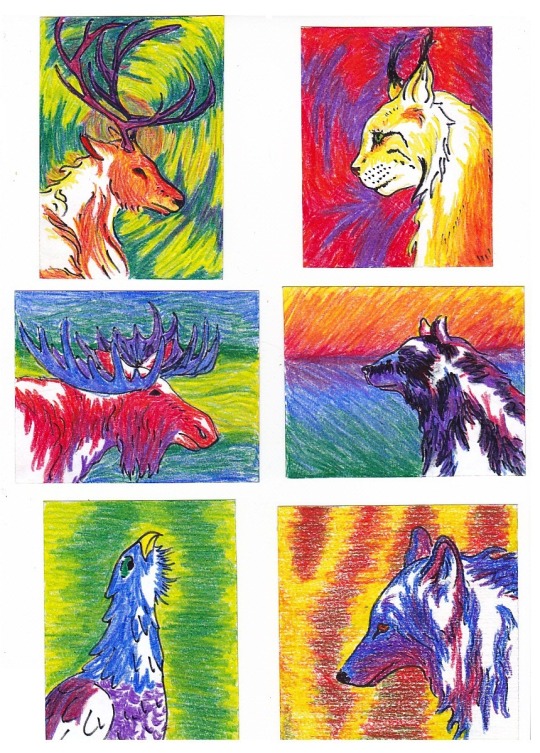

School work, and strangely enough still love them.

0 notes

Photo

Progress of a picture that was drawn for my mother as another birthday present. The sketch was created in my school years.

0 notes

Photo

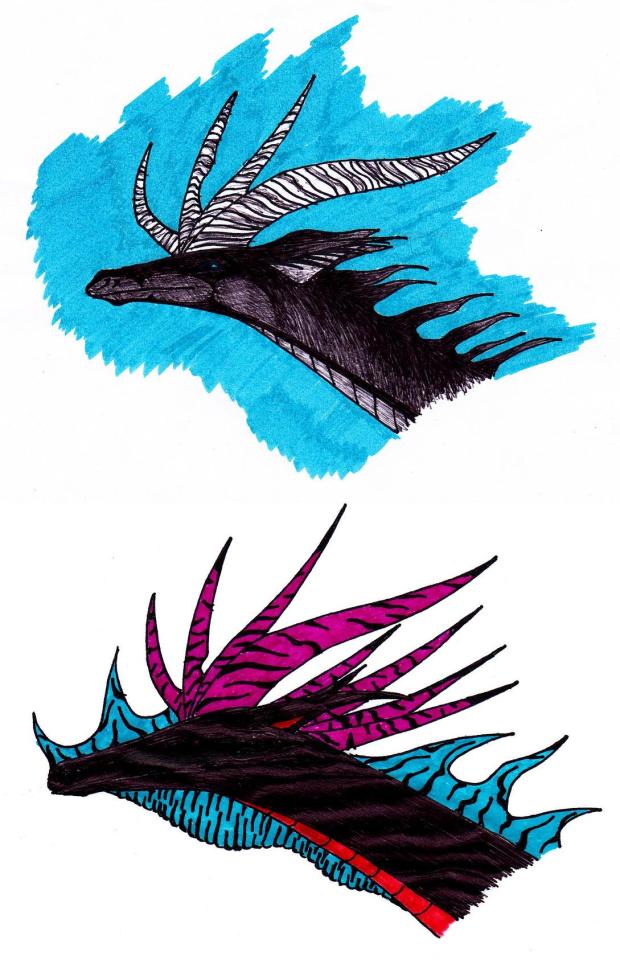

The first three are digital but the remaining are all drawn on paper.

Those first three were very fun to draw, though I could say that about all. What sets these thre apart is that I can spend at least long minutes switching back and forth between the two sketches as I always find it intriguing to see the differences.

I suppose the next two blachish dragonheads could be considered as a sort of transition between western and eastern dragons.

The red dragons -along with the wingless one- are one of the personal favourites. There is fault in the design but that is because they were drawn with pen; they weren’t sketched with pencil first.

Ah, the wingless one... Even though its a perfect sketch I have yet to properly draw it. I started it but it just doesn’t feel and seem right. It looks better in graphite. Perhaps some monochrome background will do it some justice...

The very last picture is a painting tha my brother and me made together for mother’s birthday a gift. I say together but I believe I can say that the 3/4 of the picture is my work; I made the eastern dragon and the whole background while Barni drew the western dragon.

0 notes

Photo

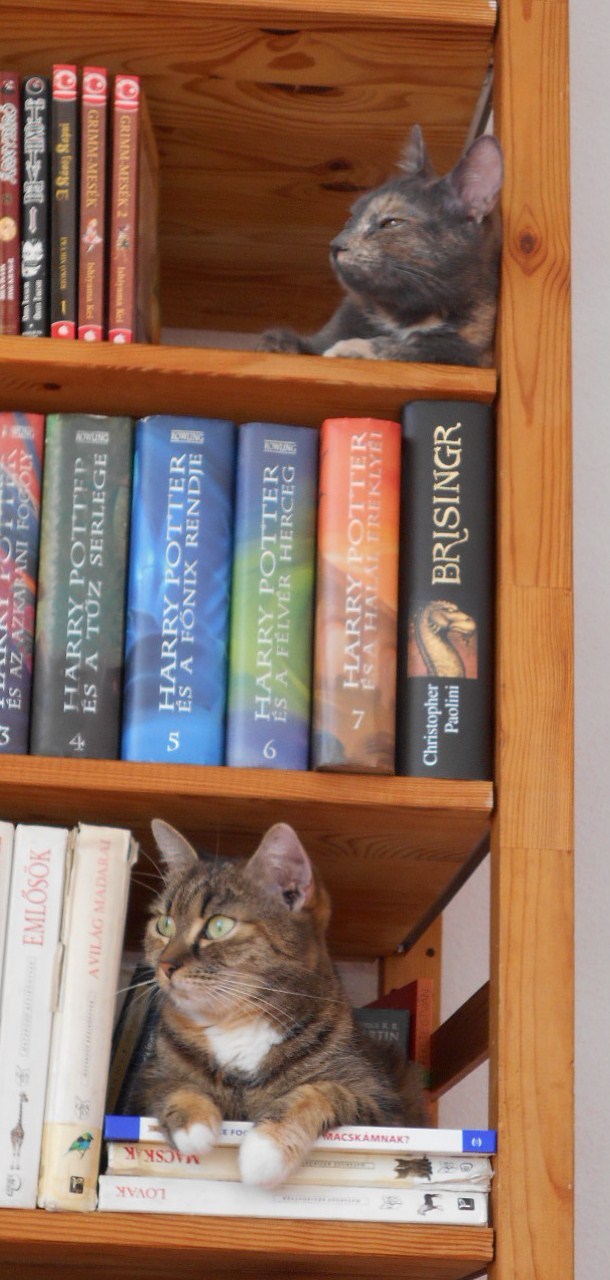

Here is Kleó (KLEH-aw), my brother’s cat. She was found on the site kiscica.hu (it would catling.com in English). Originally it was Barni’s ex-girlfriend, Szandi (SAWN-dee), wo wanted a cat, and my brother -being a devoted boyfriend to a fault- complied. Couple of years later mentioned ex-girlfriend wanted a hamster too, and hearing this I couln’t restrain myself from asking my brother “you know that hamster will be neurotic, right?”

Time flew and the girl went out of my brother’s life but the cat nad the hamster remained though mentioned hamster is already feasting in the heavenly granries. I think it was better like this for the poor creature because if it didn’t became neurotic from Kleó’s harassment then it surely would by now...

By the way the last five pictures were taken in Orosháza, in my maternal gradparents’s house (though they moved to Vác a couple of years ago on the advice of my maternal uncle). There was a time in my life when I lived with them to help both grandma and gradpa. Grandma is diabetic and was about to be 86 years old (now she will be 90!), so I kind of chaperoned her; this helped to both of my grandparents as grandma wasn’t alone and grandpa was free to do his own business without fearing for grandma’s safety. It happened during that time, that my brother went to spend his holiday with Szandi in Croatia, and I agreed to take care of Kleó. (I missed Csoki, my first cat, who I left behind Eger, in my father’s house, so I simply needed another creature around me.)

As you can see Kleó has her own humorous moments too, even now when she is already neutralized.

0 notes

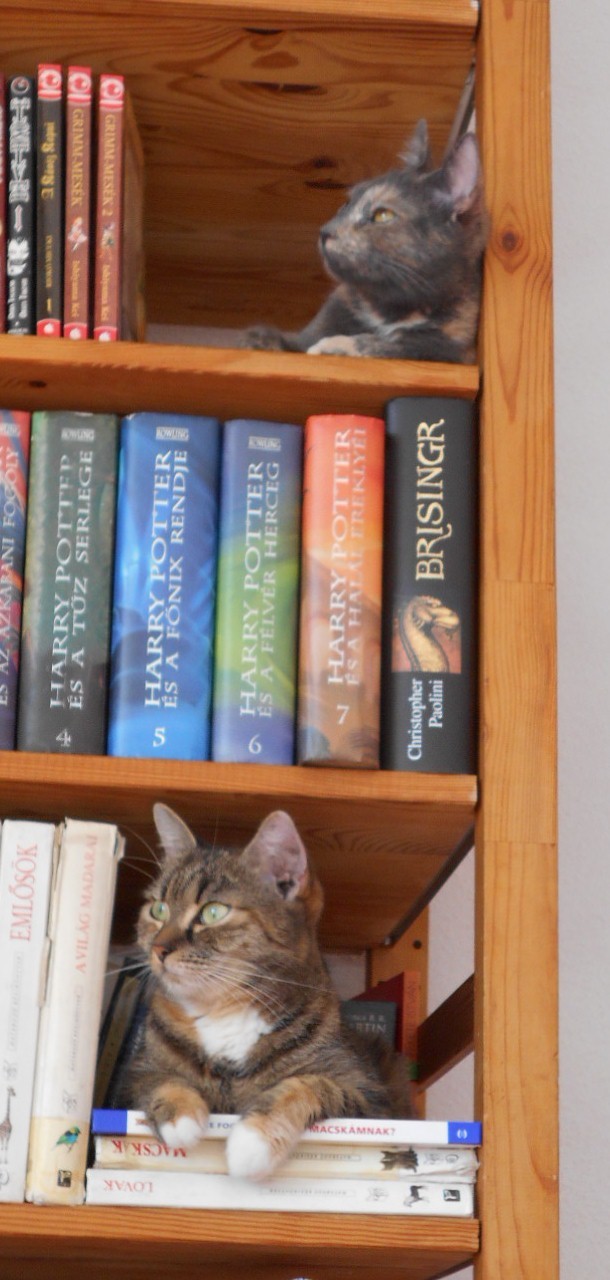

Photo

Most of the times these two sleeps separately, but sometimes something possesses them to be in each other’s vicinity. Kleó’s prefers to sleep and eat, since Szomi’s arrival it is even more true but, of course, Szomi being a lively cat she needs some action.

There are times when Szomi is content with running up on the wall, pushing herself from it then, racing across my bed, rushes up to the top of the bookcase, then comes down after a few moments, and repeats the whole from the beginning. There are also times when the mentioned method is not enough and Szomi sees Kleó nearby and decides that her senior needs a little activity.

Since Kleó is a neutralized cat, I think she can’t appreciate Szomi’s efforts adequately but knowing how Szom can be so rambunctious, brash and impertinent... Well, I can understand why Kleó is so unamused.

0 notes