Text

🌿Whats Happening in the Garden?🌿

Milkweed Pods: Nature's Tiny Time Capsules at the Stephenson House Prairie Garden

In the buzzing heart of the Stephenson House prairie garden, nestled among native grasses and wildflowers, you’ll find an unassuming marvel—milkweed pods. These soft, spiky vessels are more than mere plant parts; they’re ecological powerhouses and historical curiosities.

Life Support for Monarchs

Milkweed plants play a starring role in the monarch butterfly's life cycle. The leaves serve as the sole food source for monarch caterpillars, and the pods—those light green, armor-like structures—carry the next generation of milkweed seeds. When ripe, they split open dramatically to release silky parachutes that catch the wind, ensuring milkweed's continued spread across the prairie.

Pollinator Magnet

Before the pods emerge, milkweed blooms in clusters of tiny, fragrant flowers. These blooms attract bees, butterflies, and beneficial insects, turning the Stephenson House prairie garden into a seasonal stage for pollinator performance. Once the pollination show ends, the plant shifts into seed-production mode, growing the iconic pods that carry the promise of next year’s habitat.

History in Every Husk

Beyond their ecological value, milkweed pods have a historical tale to tell. During World War II, the silk from inside these pods was collected as a buoyant material for life jackets when kapok supplies dried up. Native Americans also found use for the plant—utilizing it medicinally and even crafting twine from its fibrous stalks.

A Living Classroom

Incorporating milkweed into the Stephenson House garden isn’t just a nod to biodiversity—it’s a way to educate visitors about conservation, history, and interconnectedness. The spiny pods are visual and tactile gateways to bigger stories: of migration, survival, and the quiet power of native plants.

So next time you’re wandering through the grounds at Stephenson House, pause beside a milkweed stem. Beneath its prickly surface lies a world of wonder—waiting for a gust of wind to set the next chapter free

0 notes

Text

We weirdos have to stick together. 😏 #tourguide #museumlife #history #museum #stephensonhouse #StephensonHouseMuseum #justhavingfun #tourguide #funny #weirdo

1 note

·

View note

Text

When your fairy godmother is clearly on backorder.

#musuem #stephensonhouse #history #funny #tourguide #shrek2 #shrek #museumlife #StephensonHouseMuseum #justhavingfun #uglystepsister

0 notes

Text

Skills that Made History, No Electricity Required, Part 11: The Papillote Iron

In the 1820s, achieving those perfect face-framing curls wasn’t just a fashion choice—it was a heated affair! Enter the papillote iron: a slender metal tong you’d warm in the fire or on the hearth. Once hot (but hopefully not too hot), pomade was applied to small sections of hair then rolled into curls and covered with papers to protect them from the heat before applying the iron. No electricity, no safety settings—just guts, heat, and a steady hand. Beauty was pain… or at least a few singed ends away.

#tourguide #museumlife #history #museum #stephensonhouse #StephensonHouseMuseum #justhavingfun #justkidding #beauty #curlingiron #hair #hairtok #oldbeautyhacks #19century

0 notes

Text

Sometimes it takes her a second

#tourguide #funny #history #fyp #stephensonhouse #musuem

1 note

·

View note

Text

Not everyone’s cup of tea. More like a cracked teacup filled with glitter and poor decisions.

#tourguide #museumlife #history #museum #stephensonhouse #StephensonHouseMuseum #justhavingfun #justhavingfun #weirdo #funny

0 notes

Text

Skills that Made History, No Electricity Required, Part 10: 🔥 The Bed Warmer🔥

Before electric blankets folks in the early 1800s had a fiery little secret for surviving icy sheets: the bed warmer. Picture this--a lidded metal pan (often brass or copper) filled with hot embers, slid between the sheets like a toasty ghost of comfort. Handled with care (and a long wooden handle), it warmed the bed without scorching the linens (hopefully, accidents did happen). Used by household staff or the lady of the house, it was both a practical tool and a subtle flex of status. Just don't leave it between the sheets too long... unless you fancy a smoldering cautionary tale.

#tourguide #museumlife #history #museum #stephensonhouse #StephensonHouseMuseum #funny #SkillsThatMadeHistory #Bedwarmer #NoElectricityRequired #StephensonHouse1820

0 notes

Text

When everyone says "Your job must be so cool!" It is until you're in a corset and multiple petticoats on a 98-degree day trying to wrestle a gigantic spinning wheel from unneath one of the beds (it's stored there). Needless to say, it was a struggle.

#funny #tourguide #museumlife #history #museum #stephensonhouse #StephensonHouseMuseum #justhavingfun #diehard #brucewillis

0 notes

Text

🌿 Blackberry Lily: A Hidden Gem of the Heirloom Garden 🌿

Don’t let the name fool you—Blackberry Lily (Iris domestica) doesn’t grow berries OR belong to the lily family! This striking 1820s favorite blooms with bright orange petals flecked with red spots, resembling a miniature leopard. After flowering, it produces shiny black seed clusters that look just like blackberries—hence the name.

Hardy, drought-tolerant, and a favorite in historic medicinal gardens, it was grown for both its beauty and its believed healing roots.

Perfect for adding a wild pop of color and a touch of 19th-century charm to your garden! 🧡🌱

#BlackberryLily #HeirloomGarden #1820sBotany #HistoricGardens

0 notes

Text

🌿 Blackberry Lily: A Hidden Gem of the Heirloom Garden 🌿

Don’t let the name fool you—Blackberry Lily (Iris domestica) doesn’t grow berries OR belong to the lily family! This striking 1820s favorite blooms with bright orange petals flecked with red spots, resembling a miniature leopard. After flowering, it produces shiny black seed clusters that look just like blackberries—hence the name.

Hardy, drought-tolerant, and a favorite in historic medicinal gardens, it was grown for both its beauty and its believed healing roots.

Perfect for adding a wild pop of color and a touch of 19th-century charm to your garden! 🧡🌱

#BlackberryLily #HeirloomGarden #1820sBotany #HistoricGardens

0 notes

Text

🥧 “More American Than Berry Pie?” Rethinking Patriotic Desserts in 1822 Edwardsville

Today, we casually say something is “as American as apple pie.” But in the early decades of the United States—especially in frontier towns like Edwardsville, Illinois, in 1822—that phrase would have rung hollow. Apple pie was beloved, yes, but it wasn’t the most seasonal, symbolic, or statistically likely dessert served at a Fourth of July celebration.

So what was? Let’s explore the contenders.

🍒 Cherry Pie: A National Symbol, But Not Yet Ubiquitous

Cherries were brought to North America by European settlers as early as the 1600s, and French colonists planted cherry trees in the Great Lakes region, including in early Midwestern settlements like Detroit and Vincennes. By the early 1800s, sour cherries such as the Montmorency variety were thriving in the Midwest and Northeast.

Cherry pie had strong patriotic associations thanks to the George Washington cherry tree legend, and it was often served around midsummer holidays like Independence Day and Canada Day. However, commercial cherry production didn’t begin until the mid-1800s, and cherry trees were still relatively limited in number in frontier regions like Edwardsville.

Conclusion: Cherry pie was symbolically patriotic and seasonally appropriate, but likely more common in established Eastern towns than on the Illinois frontier in 1822.

🫐 Berry Pies: The Frontier Favorite

Blueberries, blackberries, raspberries, and dewberries were native to North America and abundant in the wild. Indigenous peoples and early settlers alike used them in cooking. These berries ripened in late June and July, making them ideal for Fourth of July desserts.

While the first published mention of blueberry pie didn’t appear until 1829, berry pies were almost certainly being made earlier in rural households. They were practical, rustic, and didn’t require cultivated orchards—just a good patch of woods or prairie.

Conclusion: On the frontier, berry pies were likely the most common dessert at midsummer gatherings, including Independence Day celebrations in places like Edwardsville.

🍏 Apple and Marlborough Pies: Popular, But Out of Season

Apples were a staple in early American cooking, and apple pie was widely loved. Marlborough pie—a custard-apple pie from New England—was featured in American Cookery (1796) and remained popular into the 19th century.

However, fresh apples were not in season in July, and while dried or cellared apples could be used, they lacked the celebratory freshness of summer fruit. Marlborough pie, in particular, was more common in colder months or formal occasions.

Conclusion: Apple-based pies were important, but not the star of July 4th tables in 1822.

🎆 What Would Have Been Served in Edwardsville in 1822?

Given the region’s ecology, agricultural development, and culinary practices, a Fourth of July celebration in Edwardsville likely featured:

- Berry pies (especially blackberry and raspberry)

- Shortcakes with fresh berries and cream

- Rustic tarts or cobblers

- Possibly cherry pie, if trees were locally available

- Cider cakes or other simple baked goods using preserved ingredients

🏛️ Final Verdict: What Was “More American” Than Apple Pie in 1822?

If we’re speaking symbolically and nationally: Cherry pie was “more American” than apple pie.

If we’re speaking practically and regionally—especially for a town like Edwardsville: Berry pie was the most authentically American dessert of the day. So perhaps the most accurate phrase for the time would be: “More American than berry pie.”

0 notes

Text

Liberty, Cider, and Civic Pride: Edwardsville’s Fourth of July in the 1820s

In the 1820s, the Fourth of July in Edwardsville, Illinois, was a spirited affair—equal parts patriotic fervor and frontier hospitality. As the young state of Illinois found its footing, the citizens of Edwardsville gathered in the town square to mark the nation’s birthday with speeches, music, and a hearty communal feast.

A Town Comes Together

The celebration didn’t take place at the Stephenson House, but the family played a generous role. Colonel Benjamin Stephenson, a prominent political figure and civic leader, contributed jugs of cider, kettles of meat, and candles to help light the festivities. His support reflected the spirit of the day: neighbors coming together to honor shared ideals with food, fellowship, and firecrackers.

Toasts to the Republic

One of the most cherished traditions of the day was the giving of toasts—public declarations of loyalty, hope, and sometimes pointed political commentary. According to the Edwardsville Spectator, the 4th of July celebration featured a series of such toasts, printed in full in the newspaper. Among them was one by Benjamin Stephenson himself, who raised his glass and declared:

“The Union—may it be perpetual, and its blessings descend to the latest posterity.”

These toasts, often delivered with theatrical flair, were a highlight of the day and a window into the values of the community. They celebrated liberty, honored the Founding Fathers, and occasionally took jabs at political rivals or foreign powers.

A Feast Worth Remembering

The town square likely bustled with long tables laden with roasted meats, fresh bread, and seasonal fruits. Children played nearby while adults debated politics or shared news from the frontier. The cider flowed freely, and as dusk fell, candles flickered to life—casting a warm glow over a town proud of its place in the growing republic.

A Living Legacy

Today, the Stephenson House stands as a testament to that era, offering visitors a glimpse into the lives of those who helped shape early Illinois. Though the Fourth of July celebrations took place in town, the generosity of the Stephenson family and the spirit of community they embodied remain central to the story.

0 notes

Text

The earliest known fireworks display in the United States took place on July 4, 1777, in Philadelphia, exactly one year after the Declaration of Independence was adopted. It was part of the first organized celebration of Independence Day during the Revolutionary War.

According to historical accounts, the festivities included: A 13-gun salute from the ship USS Alfred, representing the 13 colonies. Bonfires and bells ringing throughout the city. And yes—fireworks lighting up the night sky, described as “beautifully arranged” and “brilliantly illuminated”

The display was modest by today’s standards—mostly orange bursts without the vivid colors we now associate with fireworks. But it was deeply symbolic, echoing John Adams’ famous wish that the day be celebrated with “pomp and parade… bonfires and illuminations from one end of this continent to the other.”

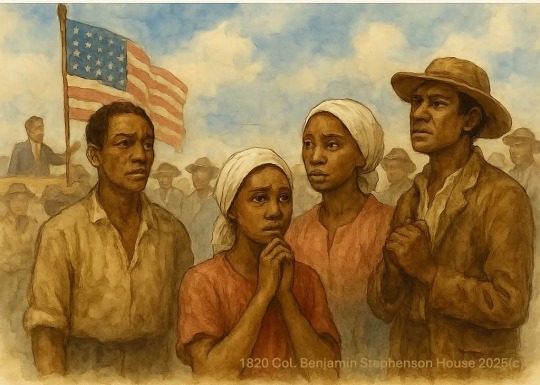

Image: modern illustration for the 1820 Col. Benjamin Stephenson House

#FourthofJuly #HistoryMoment #1777 #EarlyAmerica #FireworksFirst #PhiladelphiaPride #LivingHistory

0 notes

Text

“What to Us Is the Fourth of July?”: African American Experiences of Independence Day in 1820s Illinois and Missouri

In the early 1800s, Independence Day was one of the most celebrated holidays in the young American republic. Bands played, cannons fired, speeches rang from courthouse steps, and parades filled dusty streets with patriotic fervor. But for African Americans—both enslaved and free—the Fourth of July carried far more complex and contradictory meanings.

Freedom in Principle, Not in Practice

While white citizens celebrated beneath banners proclaiming liberty and equality, many African Americans lived in stark contradiction to those ideals. In St. Louis, Missouri, slavery was deeply rooted in state law, and free Black residents—though present—formed a small and precariously positioned minority, often subjected to restrictive legislation.

Missouri’s 1820 state constitution included a particularly controversial clause: it barred free Black and mixed-race people from entering the state and required those already residing there to register with local authorities. Although Congress admitted Missouri on the condition that this exclusionary provision would not be enforced, similar restrictions reappeared in subsequent state laws. In practice, free African Americans continued to face formidable barriers to settlement, legal residency, and freedom of movement—echoing broader patterns of racial exclusion that defined much of the antebellum Midwest.

Across the Mississippi River in Illinois, things looked different—on paper. Illinois entered the Union as a free state in 1818. Yet its constitution allowed a system of long-term indentured servitude and upheld the continued exploitation of African Americans. In southern Illinois counties like Madison and St. Clair, formerly enslaved people were often compelled to “voluntarily” sign indentures lasting 20, 30, even 99 years.

A Day of Labor, Not Liberty

Documentary evidence from this period does not indicate that Black residents—especially in rural areas like Edwardsville—participated publicly in July Fourth festivities. In slaveholding Missouri, enslaved people may have observed the fireworks and heard the cannon fire from a distance, but their roles were largely limited to labor: preparing food, serving white families, or cleaning up after events.

In Illinois, many indentured African Americans performed similar labor. Official celebrations—parades, militia reviews, public readings—centered on white civic identity. Black residents were excluded, either implicitly or by law. Even free Black citizens faced suspicion, legal discrimination, and the ever-present threat of violence or re-enslavement.

Early Roots of Resistance and Reflection

Although organized Black-led celebrations of Independence Day would emerge more clearly in the 1830s and beyond, especially in northern cities like New York and Philadelphia, seeds of reflection and resistance were already being planted by the 1820s. African Americans were not unaware of the contradiction between the nation’s founding ideals and their lived experience. Church gatherings, family discussions, and personal acts of defiance often served as quiet but powerful forms of protest.

The most famous condemnation would come later—in 1852—when Frederick Douglass asked: “What to the slave is the Fourth of July?” But even thirty years before Douglass’s speech, Black Americans were grappling with that same question, often privately, and in silence.

One Story Among Many: Free Frank McWorter

A powerful example of African American agency during this time comes from Free Frank McWorter, a formerly enslaved man who purchased his freedom in Kentucky in 1819. Over time, he also bought freedom for his wife and several children. By the late 1820s, he had moved to Illinois, where he eventually founded the town of New Philadelphia—the first U.S. town legally platted by a Black man. While McWorter’s story unfolded in Pike County, further north, it offers insight into the aspirations and struggles of many African Americans across the region.

A Holiday of Hope—and Hard Truths

For African Americans in the 1820s, the Fourth of July was a reminder of both promise and paradox. They lived in a country founded on liberty, yet many remained bound—by chains, by law, or by the long shadow of racial prejudice. Still, even amid oppression, there was hope. Freedom was not just an ideal spoken from a podium—it was a dream pursued in court petitions, in family savings, in whispered prayers.

In Edwardsville, in St. Louis, and in hundreds of communities like them, Black Americans carried on. And whether or not they joined the parade, they understood better than most the true cost of freedom—and its worth.

Suggested Sources for Further Reading

Litwack, Leon. North of Slavery: The Negro in the Free States, 1790–1860

Kachun, Mitch. Festivals of Freedom: Memory and Meaning in African American Emancipation Celebrations, 1808–1915

Kremer, Gary. Race and Meaning: The African American Experience in Missouri

Illinois State Archives: Records on Indentures and Black Laws

National Archives: Free Frank McWorter – Rediscovering Black History

0 notes

Text

Myth-Busting Early American Homes: Why Were Kitchens Detached?

You've heard it: "Fear of fire made early Americans build kitchens separate from the house."

But that’s a myth — and here's why:

Fireplaces Were Everywhere: Early homes often had multiple fireplaces — in parlors, bedrooms, even basements. If fire was the biggest concern, why put so many open flames inside the main house?

Summer Heat: A blazing hearth could turn a home into an oven in warm months. Detached “summer kitchens” helped keep living spaces cooler.

Odors & Smoke: Cooking was messy and smoky. Separating the kitchen kept strong smells and soot out of the main house.

Insect Control: Food smells drew flies, mice, and pests — easier to manage if confined to a separate building.

Too Close for Fire Safety: Detached kitchens were often just steps from the main house. If a kitchen did catch fire, it was close enough to ignite the house anyway — so fire prevention doesn’t fully explain the design.

👉 Bottom Line: Detached kitchens made life cleaner, cooler, and more controlled — but not necessarily safer from fire. Let's stop repeating the fire myth and start sharing the real story.

Sources:

The American House – Mary Mix Foley

Historic American Buildings Survey (Library of Congress)

Old Sturbridge Village and Colonial Williamsburg research

0 notes

Text

🌿 Lavender in Bloom—and in History! 🌿

Yesterday at the 1820 Col. Benjamin Stephenson House, we harvested our beautiful Provence Lavender and began the traditional process of tying and hanging it to dry today—just as it might have been done two centuries ago.

But what would lavender have been used for in the 1820s?

A Fragrant Staple in Early American Homes

In the early 19th century, lavender wasn’t just appreciated for its beauty and scent—it was a practical herb with many uses in daily life:

Household Freshener – Dried lavender was tucked into linen drawers, closets, and even bedding to ward off moths and leave behind a clean, pleasant scent.

Personal Hygiene – Before the era of modern deodorants and soaps, lavender was a key ingredient in homemade toiletries, sachets, and washing waters. Its scent was associated with cleanliness and refinement.

Medicinal Purposes – Lavender was believed to calm nerves, relieve headaches, and aid with sleep. It might be brewed into teas or distilled into oil for soothing balms or tinctures.

Symbol of Gentility – A sprig of lavender in a parlor or worn in clothing signified good taste and domestic elegance, fitting for a prominent family like the Stephensons.

As we hang our freshly harvested lavender in the kitchen we're not just preserving a plant—we're keeping alive the traditions and rhythms of a household from the 1820s.

Come visit us soon and experience how history still smells sweet at the Col. Benjamin Stephenson House!

#LivingHistory #1820House #HistoricLavender #ColonialLife #StephensonHouse #ProvenceLavender #HerbalHistory #LavenderHarvest

0 notes

Text

🧵 Skills that Made History – No Electricity Required, Part 8: Bobbin Lace

Before fast fashion and sewing machines, lace was made by hand — with dozens of bobbins, a pillow, and the patience of a saint.

In the 1820s, bobbin lace was a delicate art passed down through generations, used to decorate collars, cuffs, and bonnets... assuming you didn’t tie yourself in knots first. It took serious patience and skill.

No plug, no pattern downloads — just pure brainpower and busy fingers. Could you keep all those threads straight without losing your mind (or your bobbins)?

#tourguide #museumlife #history #museum #stephensonhouse #StephensonHouseMuseum #justhavingfun #funny #SkillsThatMadeHistory #BobbinLace #NoElectricityRequired #1820sCrafts #HandmadeHistory #StephensonHouse1820 #VintageSkills #LivingHistory #HistoricFashion

0 notes