#Dmitry Golovnin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Chowantschina - Grand Théâtre de Genève 28.03.2025 #calixtobieito #alejandropérez #genf #modestmussorgskji #operalover #russland #musicwasmyfirstloveanditwillbemylast #review

#Alejo Pérez#Arnold Rutkowski#Calixto Bieito#Chowantschina#Chœur du Grand Theâtre de Genève#Dmitry Golovnin#Dmitry Ulyanov#Ekaterina Bakanova#Emanuel Tomljenović#Genève#Genf#Grand Théâtre de Genève#Igor Gnidii#Kritik#Liene Kinča#Maîtrise du Conservatoire populaire de Genève#Mark Biggins#MARK KURMANBAYEV#Michael J. Scott#Modest Mussorgskij#Oper#opera#operalover#Orchestra de la Suisse Romande#Raehann Bryce-DAvis#Rémi Garin#Rebecca Ringst#Rezension#Sarah Derendinger#Taras Shtonda

0 notes

Text

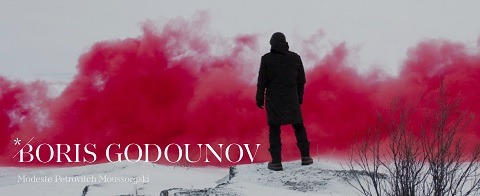

TEATRO ALLA SCALA: BORIS GODUNOV

TEATRO ALLA SCALA: BORIS GODUNOV

Ildar Abdrazakov com a Boris. Producció de Kasper Holten. Fotografia de © Brescia e Amisano – Teatro alla Scala Una inauguració de la Scala encara és quelcom important, continua sent un referent de les temporades operístiques i malgrat que el teatre milanès ha perdut aquella aurèola de temple referencial, exigent i entusiasta per esdevenir com totes les grans cases d’òpera mundial, centres més…

View On WordPress

#Agnieszka Rehlis#Ain Anger#Alexander Kravets#Alexey Markov#Anna Denisova#Coro ed orchestra del Teatro alla Scala di Milano#Dmitry Golovnin#Ildar Abdrakazov#Kasper Holten#Lilly Jørstad#Maria Barakova#Modest Mussorgski#Norbert Ernst#Oleg Budaratskiy#Riccardo Chailly#Roman Astakhov#Stanislav Trofimov#Vassily Solodkyy#Yaroslav Abaimov

0 notes

Text

Kirill Petrenko e i Berliner Philharmoniker al Festspielhaus Baden-Baden - Mazeppa

Kirill Petrenko e i Berliner Philharmoniker al Festspielhaus Baden-Baden – Mazeppa

Foto ©Monika Rittershaus Kirill Petrenko e i Berliner Philharmoniker hanno concluso la loro residence autunnale a Baden-Baden con due esecuzioni concertanti dell’ opera Mazeppa di Tschaikowsky, (more…)

View On WordPress

#baden baden#berliner philharmoniker#canto#critica#dimitry ivashchenko#dmitry golovnin#dmitry ulyanow#kirill petrenko#mazeppa#opera#peretyatko#rundfunkchor berlin#teatro#tschaikowsky#vladimir sulimsky

0 notes

Text

Review #69: The Gambler at Lithuanian National Opera

12 September 2020, recording from 12 February 2020 on Operavision

I know three things: 1) I love Prokofiev 2) I love Asmik Grigorian 3) I’m going to have to restrain myself not to turn this review into a 2000 word rant on online casinos.

Director (and Asmik Grigorian’s husband) Vasily Barkhatov describes this production as his personal rage against internet gambling, so basically we’re on the same brainwave. Prokofiev’s music suits exceptionally well to a current-day setting, and boy are the themes of gambling, addiction, economic strife, violence, and power imbalances ever-relevant. The opera is set entirely in a hostel and the characters never leave the stage. That requires an insane amount of acting energy from the singers, and especially huge props goes to lead tenor Dmitry Golovnin for an amazing perfrormance.

The aesthetics of the opera was ON POINT to precisely showcase the class and nationality of the characters in this set. Everyone on the eastern side of the Baltic Sea knows which department store that shopping bag comes from and what kind of people frequent it. Also, yes, grandmaman is wearing a Sochi 2014 Olympics jacket.

Now in corona times especially this isn’t an unfamiliar sight, but isolation is in no way a recent phenomenon. [Here I’ve deleted that internet gambling rant. Let’s just say that I bet that lockdowns have churned out disgustingly huge profits for the predatory online casinos.]

The vibrancy of Prokofiev’s music had my heart palpitating as if it was my own money on the line. I felt the thrill of roulette, the high of a win, the low of loss. The Gambler is truly one of the most underrated operas out there.

Bonus: I’m also gonna sing my praises for the EU whom we stan on principle. Funds from the EU facilitate projects like Operavision. It’s an entire mess in more than one way but the idea of an economically and democratically unified Europe is too important to give up on. So, my fellow European opera enthusiasts, next time an EU election comes along, please vote, because low voter turnout is what leads to actual literal n*zis making decisions that affect you.

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Enjoy this Teatro Colon’s production of “Rusalka” in streaming. With Ana María Martínez, Dmitry Golovnin, Ante Jerkunica and cast

1 note

·

View note

Text

Lope Hernan Chacón: Mussorgsky – Boris Godunov (Paris, 2018)

Modest Mussorgsky – Boris Godunov L’Opéra national de Paris, 2018

Vladimir Jurowski, Ivo van Hove, Ildar Abdrazakov, Evdokia Malevskaya, Ruzan Mantashyan, Alexandra Durseneva, Maxim Paster, Boris Pinkhasovich, Ain Anger, Dmitry Golovnin, Evgeny Nikitin, Peter Bronder, Elena Manistina, Vasily Efimov, Mikhail Timoshenko, Maxim Mikhailov, Luca Sannai

Culturebox – 7 June 2018

There’s a sense of the epic in Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov that is entirely in keeping with the importance of the period in Russian history and with the nature of the Russian characteristics displayed in it. What is also essential about Mussorgsky’s epic vision for the work is its ability not just to capture a sense intimacy and personal conflict within that historical drama – a common enough characteristic in opera – but how he is able to make those personal sentiments just as grand and epic without losing their human character. Mussorgsky takes human sentiments of sadness, regret, guilt and internal conflict and gives them a Macbeth-like Shakespearean depth and complexity on a scale that befits their importance.

You get a sense of that right from the start in the opera, with the people of Russia calling out in chorus for him to be their new ruler. You also get a sense of how Boris feels about this from his very first line – “My soul grieves”. He has a heavy duty to perform to live up to the expectations of the Russian people and do them justice, but there is also a sense of guilt and remorse for the manner in which he comes to power, with rumours already accusing him of murdering the young Tsarevitch Dmitriy from the line of Ivan the Terrible to ascend to the throne. An accumulation of misfortune and other forces, including the rise of a Pretender to the throne in Lithuania, turns the people against Godunov, and the combined results strike the Tsar in deeply troubling ways. Finding a balance of scale between epic and intimate is one matter, but there is also the consideration of which version of Boris Godunov is the most authentic and effective in achieving the necessary impact. Historically it’s been the revised 1872 version that has been most commonly used, and understandably so as it contains many extensions to Mussorgsky’s brilliant score, but Rimsky-Korsakov’s reworking of the original materials has also been popular. Gradually however, we are seeing more productions of the original 1869 version, commonly with a few additions from the revised 1872 version that are deemed too good to be left out.

The 2018 Paris production however, directed by Ivo van Hove and conducted by Vladimir Jurowski, takes very much a purist approach by sticking to the complete 1869 original version of Boris Godunov, with no Polish Act nor any of the 1872 additions. It’s purist at least in musical terms, but clearly with the controversial Belgian theatre director Ivo van Hove involved in the project, it’s going to be anything but purist as far as the staging goes. That presents an intriguing team that should find a good balance between the grandly epic and the deeper underlying personal sentiments, and in many respects both sides of the work are well represented, but the production seems to be more effective for the choice of the stripped down force of the 1869 version than for anything that Jurowski or van Hove bring to the work.

As is usually the case with this director, Ivo van Hove relies on a minimal staging, abstract-modern with no period or historical trappings. The use of the space, opened up with back projections of the Russian people and landscapes that are mirrored to the sides, permits a sense of epic scale that can also close the work down to a more intimate level of intensity. A staircase is often present, leading up and also leading down beneath the stage, the symbolism of which is clearly apparent, representing rise and fall, and the separation of the ruling classes from the people. Other scenes are effectively austere, such as between Pimen and Grigoriy in the cell of the monastery in Chudov, needing no further elaboration than two people in near-darkness recounting events in words and divulging the thoughts that run through their minds.

How much of the success in getting this across is down to effective direction, how much is down to the musical performance and how much of this is simply down to the power of the story and Mussorgsky’s scoring of it is debatable, but it seems to me that it’s Mussorgsky’s score that does the bulk of the work. Even then Jurowski‘s conducting seems rather restrained and unfocussed, although it’s hard to judge fairly from an internet stream (I’ll be listening again more closely to the live radio broadcast on France Musique this weekend), and yet there’s no question that the drama and the dynamic is all there. Likewise Ivo van Hove doesn’t seem to bring much to an interpretation of the drama, but it doesn’t get in the way of it either.

There are a few stylistic touches applied, but perhaps the only significant twist is at the conclusion. Not only does Boris Godunov finally and dramatically succumb to the pressures of family problems, famine blighting the country and growing instability in his mind over his murder of Dmitriy, but his son dies too at the hand of the Pretender Grigoriy. It’s a dark dramatic moment that doubles down on the music that Mussorgsky provides for this finale and, as Boris’s son’s reign was indeed cut short in deference to the False Dmitriy, it even effectively conveys the suggestion in Mussorgsky’s music that the conflict and turmoil of this historical period is far from over.

Ideally you want a Russian cast in Boris Godunov for maximum effectiveness, at least in the principal roles, and there’s little to find fault with in team assembled for the Paris production. Ildar Abdrazakov is perhaps a little too smooth and lacking the necessary depth and edge to get across the full conflict of Boris Godunov. He sings the role well, but there’s not enough emotion in the voice and too much overplaying in the acting to try to compensate for it. Ain Anger is an appropriately grave austere and occasionally ominous Pimen, there’s a similar good balance of restraint and gravity in Maxim Paster‘s Shuysky, and Vasily Efimov brings vocal colour and some hard truths as the Holy Fool. Lots to enjoy in the singing performances then, with strong a strong chorus combining to make a convincing case for the original 1869 version of Boris Godunov becoming the canonical version of this great work.

Links: L’Opéra de Paris, Culturebox

View Source

from WordPress https://ift.tt/2KnI3Yc via Ver Fuente

0 notes

Text

Went to see ‘The Flying Dutchman’. Officially hate people when they think commenting on everything all the time is a good idea. And dumb commenting at that. It's OPERA not a football match go figure! Yes passions are egagerated and the director's I'd say touch didn't help much with smoothing the angles. It was Mikhailovsky theatre not the Mariinsky this time and they are notorious for Regietheater but the thing is I even like it at times - like when I went to see 'Le Nozze Di Figaro' there - it was crazy but real fun! Today... well there were some really strong ideas but overall impression of toooo muccchhh was too much. And the worst part is that this approach from the theatre kind of warrants all kinds of unpalatable behaviour from the public. I'm not advocating treating opera as a sacred cow far from it but some people in the audience today clearly couldn't get over the Wagner's work not being treated this way... So I dunno. The result? Well, I usually switch off from the world and my inner monologue and get high on opera but today that state was hard to reach. Oh... and the music - I sat above the pit - always love watching what's going on there))) The singers did a fine job. I liked Eric (Dmitry Golovnin) especially! Hope to see more of him next season.

0 notes

Text

La stagione lirica dell’Opéra di Lyon si è aperta con L’ange de feu, l’opera postuma di Prokofiev per troppo tempo dimenticata. Una scelta che ha colto nel segno, accolta con grande entusiasmo tanto dal pubblico quanto dalla critica.

L’ange de feu possiede una storia travagliata e à baton rompu, quasi un sentimento speculare alla tematica dell’opera: una follia totalizzante che abolisce il concetto di proficuità. Nel 1919 Prokofiev scopre il romanzo eponimo di Valéri Brjusov, pubblicato dodici anni prima sulla rivista Vesy e inizia a lavorare ad libretto. Ma il concepimento dell’opera sarà difficoltoso proprio per la situazione nella quale si trova il compositore in quel momento. Trasferitosi negli Stati Uniti, Prokofiev subisce le critiche e le ironie dei critici americani dell’epoca. Il compositore decide quindi di ritirarsi in un piccolo villaggio delle Alpi bavaresi per lavorare assiduamente all’opera, in particolar modo per quanto riguarda la partitura. Il lavoro giungerà al termine solo nel 1926 ma la prima rappresentazione avverrà solo dopo la morte del compositore, nel 1954 al Théâtre des Champs-Elysées a Parigi, e in francese. La prima rappresentazione scenica avrà luogo alla Fenice l’anno successivo, sotto la direzione di Nino Sanzogno e con la regia di Giorgio Strelher, mentre la prima rappresentazione originale avverrà solo nel 1981 a Praga.

Ruprecht (Laurent Naouri) è un cavaliere di ritorno dalle Americhe e, deciso a fare tappa in una modesta locanda tedesca, si interroga sulle urla provenienti dalla stanza adiacente. La regia di Benedict Andrews immagina questo ascolto e questa follia attraverso la moltiplicazione dei due personaggi, creando un vortice umano mascherato e inquietante. Facendo irruzione in essa, il cavaliere scopre una donna, Renata (Ausrine Stundyte) parzialmente svestita – rappresentata qui come una prostituta (i costumi i Victoria Behr producono un forte effetto di straniamento durante tutto lo svolgimento dell’opera) che prega una forza invisibile di lasciarla in pace. Gettandosi nelle braccia di Ruprecht, Renata lo chiama per nome e questo terrorizza il cavaliere che si interroga su questa strana magia. La visione (che appartiene solo a chi la subisce) di Renata ci permette di sentire immediatamente la temperatura della drammaturgia e si avvicina pericolosamente all’isteria e all’epilessia. Ruprecht interviene pi�� che come un cavaliere salvatore, come un esorcista invocato dalla stessa posseduta. Renata si trova, dunque, a raccontare la sua visione e la propria persecuzione/fissazione per questo essere sovrannaturale. Ecco che la scena diviene una ruota di souvenir dolci e inquietanti, accompagnati dall’angelo di fuoco, Madiel, solito giocare con lei fino a quando, la giovane Renata inizia a provare il desiderio di unirsi carnalmente con lui. La promessa dell’angelo è quella di tornare dopo un anno, sotto le sembianze umane. Renata crede di ritrovare il suo angelo nel conte Heinrich con il quale vive un’intensa relazione. Ma Renata verrà lasciata dal conte e da quel momento ella vive in preda alle allucinazioni. La locanda non è più il luogo dove sostare tranquillamente, e consigliati da una veggente (Mairam Sokolova) inviata dalla locandiera (Margarita Nekrasova), Renata e Ruprecht decidono di partire a Colonia alla ricerca del conte.

La scenografia concepita per il secondo atto è quanto di più minimalista e tagliente vi possa essere e provoca uno slittamento di senso e una non perfetta aderenza tra il testo e la realizzazione scenica. Colonia è ridotta ad una lingua di terreno che fende la scena e ciò provoca un effetto affatto disturbante ed estremamente arricchente. La ricerca del conte è sterile ma Ruprecht riesce a incontrare il sapiente e mago Agrippa di Netteshein (Dmitry Golovnin), senza che questi possa rivelargli i segreti della magia. La scelta di vestire Agrippa come un mago di cabaret ci palesa la chiave di lettura scenica dell’opera: la discrasia testo-immagine è l’innovazione e la mescolanza epocale, una linea sensibile lanciata all’interno del tempo che non rispetta la filologia per aprire l’opera ad una lettura trasversale incessante.

La follia visionaria di Renata cresce di importanza e di influenza e il povero Ruprecht è ridotto a schiavo delle minacce e dei desideri della protagonista. Egli è incitato a sfidare a duello il conte Heinrich ma, alla vigilia del giorno stabilito, Renata lo implora di lasciarlo vivere poiché egli è il suo angelo di fuoco. Ruprecht riuscirà a sopravvivere miracolosamente al duello. Mossa dalla compassione e profondamente colpita dalla drammatica scena, Renata dichiara il proprio amore per il valente cavaliere.

L’instabilità decisionale di Renata è la forza dinamica dell’opera, ciò che la fonda e che la mantiene nella sua tensione. Dopo essersi dichiarata a Ruprecht, Renata cambia idea ed è risoluta a farsi suora per scampare al diavolo (che ora vede in Ruprecht) e per salvarlo dalla dannazione. Si apre quindi, in mezzo all’opera, uno spazio che accoglie una scena apparentemente decontestualizzata. Sulla piazza di Colonia, Faust (Taras Shtonda) e Mefistofele (Dmitry Golovnin) disquisiscono sul carattere fittizio delle cose umane. Quest’ultimo divora il figlio del padrone della locanda, facendolo in seguito apparire nel bidone della spazzatura poco più lontano. La discrasia testo-immagine continua anche qui: se i clienti ordinano vino, essi ricevono una volgare lattina di birra.

L’ultimo atto è un crescendo epico e drammatico e la perfetta direzione dell’orchestra del maestro Kazushi Ono sottolinea veementemente la forza della partitura di Prokofiev. Le suore de convento formano un coro greco a due voci che didascalizza i sentimenti e le azioni che si svolgono sulla scena. L’inquisitore (Almas Svilpa) chiamato per indagare sugli strani fenomeni che stanno avvenendo nel convento, vestito come un semplice prete di provincia, interroga le novizie che iniziano a mostrare i segni di una possessione demoniaca. La follia di Renata si rivela essere una malattia pandemica che si sparge e che ingloba tutto. Sotto gli occhi di Faust e Mefistofele, accompagnati dall’impotente Ruprecht, le forze del male divorano tutto. Il convento è posseduto e l’inquisitore diviene egli stesso vittima del potere occulto. Egli si rivela l’angelo del fuoco mentre Renata scompare tra le fiamme del rogo purificatore.

La prima di L’ange de feu si chiude qui, tra gli applausi e i “Bravo” dell’esigente pubblico lionese, conquistato da quest’opera perfettamente riuscita.

Le public lyonnais a accueilli avec enthousiasme l’opéra L’ange de feu de Prokofiev dans la courageuse et audacieuse mise en scène de Benedict Andrews. Un succès mérité pour un opéra posthume du compositeur russe qui a inauguré la saison à l’Opéra de Lyon.

Lo spettacolo va in scena: Opéra de Lyon Place de la Comédie – Lione martedì 11, giovedì 13, sabato 15, lunedì 17, mercoledì 19 e venerdì 21 ottobre ore 20.00, domenica 23 ottobre ore 16.00

L’Opéra de Lyon presenta L’ange de feu di Sergej Prokofiev

opera in cinque atti, 1954 (versione concerto), 1955 (versione scenica) libretto di Sergej Prokofiev, dall’opera di Valerij Brjusov in russo

direzione musicale Kazushi Ono messa in scena Benedict Andrews collaborazione artistica alla messa in scena Tamara Heimbrock drammaturgia Pavel B. Jiracek decoro Johannes Schütz costumi Victoria Behr luci Diego Leetz direttore dei cori Philip White

Ruprecht Laurent Naouri Renata Ausrine Stundyte la locandiera Margarita Nekrasova la veggente / madre superiora Mairam Sokolova Jakob Glock Vasily Efimov Agrippa von Nettesheim / Méphistophélès Dmitry Golovnin Faust Taras Shtonda servitore / l’oste Ivan Thirion inquisitore / Heinrich Almas Svilpa

orchestra e cori dell’Opéra de Lyon produzione della Komishe Oper de Berlin

www.opera-lyon.com

#gallery-0-3 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-3 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 33%; } #gallery-0-3 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-3 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

©Pierre Maurin

©Pierre Maurin

©Pierre Maurin

©Pierre Maurin

©Pierre Maurin

©Pierre Maurin

©Pierre Maurin

©Pierre Maurin

Kazushi Ono ©Pierre Maurin

Ausrine Stundyte ©Schneider Photography

Laurent Naouri ©Bernard Martinez

L’ange de feu | Opéra de Lyon La stagione lirica dell’Opéra di Lyon si è aperta con L’ange de feu, l’opera postuma di Prokofiev per troppo tempo dimenticata.

#Ausrine Stundyte#Benedict Andrews#Diego Leetz#Dmitry Golovnin#Heinrich Almas Svilpa#Ivan Thirion#Johannes Schütz#Kazushi Ono#Laurent Naouri#Mairam Sokolova#Margarita Nekrasova#Pavel B. Jiracek#Philip White#Tamara Heimbrock#Taras Shtonda#Vasily Efimov#Victoria Behr

0 notes