#Joint Task Force Southern Border

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

#youtube#1st Battalion#Joint Task Force Southern Border#2nd Stryker Brigade Combat Team#4th Infantry Division#Deming New Mexico#Border Security#National Security#Border Patrol#Stryker Vehicles#Southern Border Patrol#Military Training#Military Patrol#Deming NM#tactical patrol#border security#national security#southern border patrol#combat team#Stryker vehicles#deployment#border enforcement#us mexico border update#us mexico border#mexico border

1 note

·

View note

Text

TOKYO (AP) — Japan this week confirmed that two Chinese aircraft carriers have operated together for the first time in the Pacific, fueling Tokyo's concern about Beijing's rapidly expanding military activity far beyond its borders.

Carriers are considered critical to projecting power at a distance. China routinely sends coast guard vessels, warships and warplanes to areas around the disputed East China Sea islands, but now it is going as far as what's called the second-island chain that includes Guam — a U.S. territory. A single Chinese carrier has ventured into the Pacific in the past, but never east of that chain until now.

Here's what to know about the latest moves by China, which has the world’s largest navy numerically.

What happened?

Japan's Defense Ministry said the two carriers, the Liaoning and the Shandong, were seen separately but almost simultaneously operating near southern islands in the Pacific for the first time. Both operated in waters off Iwo Jima, about 1,200 kilometers (750 miles) south of Tokyo, Defense Minister Gen Nakatani said Monday.

The Liaoning also sailed inside Japan's exclusive economic zone of Minamitorishima, the country's easternmost island. There was no violation of Japanese territorial waters. Still, Nakatani said Japan has expressed “concern” to the Chinese embassy.

Both carriers had warplanes take off and land. Late Wednesday, Japan’s Defense Ministry said a Chinese J-15 fighter jet that took off from the Shandong on Saturday chased a Japanese P-3C aircraft on reconnaissance duty in the area and came within an “abnormally close distance” of 45 meters (50 yards).

The Chinese jet on Sunday crossed 900 meters (980 yards) in front of the Japanese P-3C, the ministry said, adding it has strongly requested China to take measures to prevent such an “abnormal approach” that could cause accidental collisions.

Why is Japan worried?

China's military buildup and expanding area of activity have raised tensions in the region.

The Chinese carriers sailed past the first-island chain, the Pacific archipelago off the Asian mainland that includes Japan, Taiwan and part of the Philippines. The Liaoning reached farther to the second-island chain, a strategic line extending to Guam, showing China also can challenge Japan's ally, the United States.

“China apparently aims to elevate its capability of the two aircraft carriers, and to advance its operational capability of the distant sea and airspace," Nakatani said.

The defense minister vowed to further strengthen Japan's air defense on remote islands.

Japan has been accelerating its military buildup especially since 2022, including counter-strike capability, with long-range cruise missiles as deterrence to China.

What does China want?

China's navy on Tuesday confirmed the deployments, calling it part of routine training in the western Pacific “to test their capabilities in far seas protection and joint operations." It said the deployment was in compliance with international laws and not targeted at any country.

China is pursuing a vast military modernization program including ambitions of a true “blue-water” naval force capable of operating at long ranges for extended periods.

Beijing has the world’s largest navy numerically but lags far behind the United States in its number of aircraft carriers. China has three, the U.S. 11.

Washington’s numerical advantage allows it to keep a carrier, currently the USS George Washington, permanently forward-deployed to Japan.

The Pentagon has expressed concern over Beijing’s focus on building new carriers. Its latest report to Congress on Chinese defense developments noted that it "extends air defense coverage of deployed task groups beyond the range of land-based defenses, enabling operations farther from China’s shore.”

What are the carriers' abilities?

The two Chinese carriers currently in the western Pacific employ the older “ski-jump” launch method for aircraft, with a ramp at the end of a short runway to assist planes taking off. China’s first carrier, the Liaoning, was a repurposed Soviet ship. The second, the Shandong, was built in China along the Soviet design.

Its third carrier, the Fujian, launched in 2022 and is undergoing final sea trials. It is expected to be operational later this year. It is locally designed and built and employs a more modern, electromagnetic-type launch system like those developed and used by the U.S.

All three ships are conventionally powered, while all the U.S. carriers are nuclear powered, giving them the ability to operate at much greater range and more power to run advanced systems.

Satellite imagery provided to The Associated Press last year indicated China is working on a nuclear propulsion system for its carriers.

Any other recent concerns?

In August, a Chinese reconnaissance aircraft violated Japan's airspace off the southern prefecture of Nagasaki, and a Chinese survey ship violated Japanese territorial waters off another southern prefecture, Kagoshima. In September, the Liaoning and two destroyers sailed between Japan’s westernmost island of Yonaguni — just east of Taiwan — and nearby Iriomote, entering an area just outside Japan’s territorial waters where the country has some control over maritime traffic.

China routinely sends coast guard vessels and aircraft into waters and airspace surrounding the Japanese-controlled, disputed East China Sea islands to harass Japanese vessels in the area, forcing Japan to scramble jets.

Tokyo also worries about China's increased joint military activities with Russia, including joint operations of warplanes or warships around northern and southwestern Japan in recent years.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Devour (Part I)

Everything ached.

Jeanie tried to ignore the stiffness in her joints as she rolled onto her side. Dawn hadn't broken yet and that meant she might have a chance at getting everything handled today. Summoning what little strength remained in her tired bones, Jeanie forced herself out of bed and painfully donned her farm clothes. She made her way out of the bedroom and carefully descended the stairs to the double front doors. Stepping into her worn boots, she took a moment to survey the farm before she attempted to care for all of her livestock while the sun was still up.

The farmhouse was built right up against the tree line of the forest that marked the southern border of her land. Surrounding the house was her sprawling garden, dormant now that winter was closing in, but still impressive in its own way. Before Joseph and Lonnie had died, her husband and son had managed entire fields of crops, but since their deaths, Jeanie had rented the land out to neighbors and built herself a vegetable garden that met all of her personal produce needs. Beyond that were her most important sources of meat and income; the chicken coop, the pig sty and the barn. The chicken coup was the easternmost building, the barn lay directly north of the farmhouse and the sty sat farthest from the house to the west.

Each day, she had to make her rounds feeding the animals, cleaning their pens as best she could and refilling their water troughs. At fifty years old, Jeanie was not equipped to handle these tasks alone day in and day out. Her feed was delivered by her renters every Monday and a couple of local boys cleaned the barn, coop and sty reasonably well every couple of weeks in warm weather and about once a month during the coldest part of the year. During these semi-regular visits, Jeanie would head to town to look for supplies and check in with a few familiar faces. Outside of these visits and excursions though, Jeanie was on her own, and the daily workload was more than enough to keep her constantly on the brink of exhaustion.

She started at the chicken coop, throwing out seed, checking for eggs and cleaning up the feces and feathers left behind by her eleven hens and single, decrepit old rooster. Then, as she did at each stop on her circuit, she fetched a pail of water from the well near the barn and carried it back to the coup. The first trip was never bad, but each one after it became more and more arduous as her body tired and aches that never seemed to completely go away flared back to life. Her next stop was the barn where she brushed, fed and milked her two cows before mucking a section of the cramped space and making her second water run. Third was the sty. Here she fed and watered the pigs, but she left the cleaning to her two young helpers. Mucking for this lot was far too strenuous for her and the five pigs she had were large. Jeanie did not intend to give any of them the opportunity to trample or trap her in the stinking mud of their foul abode. This third trip to the well was far and pure agony for her arthritic hands. They barely had the strength to stay clenched over the bucket's handle as she trundled painfully from the well to the sty.

Even with her livestock taken care of, her work was still far from done. Hobbling over to the well for the final time, she filled a bucket to the brim and carefully walked it back to the farmhouse. Pouring a fourth of the water out of the bucket for her own use, she brought the rest to the single-horse stable attached to the east side of her home. Inside was Joseph's favorite horse, and her only remaining transportation, Red. The massive horse was old, but still strong and an easy ride. This visit with Red was usually the highlight of her day and today proved to be no different.

Slumping into the rocking chair she'd moved from the porch to the stable years ago, she slid Red's bucket toward the horse with her foot and Red lowered his shaggy head to drink. Red was a solemn beast, always had been, but he had seemed even more so since Joseph and Lonnie had passed. Their deaths had come unexpectedly and in quick succession. Lonnie had gone off to fight in Mexico while Joseph and Jeanie stayed behind to work the farm without him. Then, on one of Joseph's long trips to try and sell livestock at the various towns and markets across the territory, he had fallen ill and Jeanie had learned by letter that he had died at an inn and that she could either fetch his body herself or send men to do it for her. As if this shock hadn't been enough, she’d received word of Lonnie's death in Mexico two days later as she’d set out to collect Joseph.

Jeanie knew that if she'd been back home in North Carolina, living in a little house now left empty by the deaths of her entire living family, she would have died, either by her own hand or due to total apathy. Out here though, on the fringes of civilized life, she hadn't had that option. The animals still needed tending and to do that she needed to keep up the farm as much as she could, as cheaply as she could. She had received some money from the government after Lonnie's death and the doctor who had watched over Joseph when he'd expired had sold the remaining livestock, later sending Jeanie the full amount of sale. The total sum hadn’t been much, but it had been enough. It was seven years now since her husband and son had left her behind here on the frontier and the pain still felt as fresh as it ever had. Only the farm and her animals kept her going.

During the spring, summer and fall she had a decent amount of comers and goers to her farm and the constant human contact and things to be handled kept her distracted well enough. The winters were always hard though. It wasn't just that her personal work load almost tripled, though that was unpleasant to say the least, it was that she felt less human. Visitors came more seldomly and stayed only as long as they had to before fleeing to escape the frigid winter winds. When she wasn't running herself ragged trying to keep the animals cared for, she was trapped inside, alone, to nibble on her rationed food stores and read the same books over and over again as she waited for winter to give way to the distractions of spring. Resigning herself to that familiar fate again this evening, she patted Red on the head, gave him a light kiss on the cheek and returned to the farm house for a few hours of relaxation and a quick meal before bed.

Out of her boots, her feet radiated with pain as she walked gingerly to the kitchen. Her pantry was decently stocked with a host of pickled vegetables, various cured meats and a bit of cheese and butter. Many loaves of hearty bread were available as well, so she tore off a crust and cut herself a wedge of cheese before taking a seat at the kitchen table. She kept her eyes down at her food as she ate; looking up always brought visions of the men who had once shared this table with her in a happier time. Better just to focus on the food and then move on to bed. She needed every bit of sleep she could get.

Even after finishing her meal, Jeanie let herself rest before attempting the stairs. Descending each morning could be painful, but the ascent each night, especially in her current state of exhaustion, was downright dangerous. About twice a week she lost her footing or had a knee buckle under her, but so far she had avoided tumbling down the beautiful, but steep, farm house steps.

Tonight was not a good night. She made it halfway up before she felt the trembling creep up her right leg. Bracing herself against the creaking banister, she felt the leg go out from under her and did her best to ease down into a seated position on the steps. She had no idea how long she was forced to sit there, half asleep, waiting for her leg to stop twitching and flexing.

When it finally did, she more or less crawled up the remaining steps before standing tall and doing her best to make it to her bed uninjured. She made it safely this night, but she knew it was only a matter of time before she wound up lying in a heap at the bottom of those steps. She only hoped it happened when someone was supposed to check in, not in the middle of a damned snow storm.

Pulling her tattered comforter back, she laid down in her cold, stiff bed. Looking up at the pitch-black ceiling, Jeanie tried to find some small ounce of comfort in her current existence, but found none. Like every night since his death, all Jeanie felt was Joseph's absence. Trying unsuccessfully to push the image of the man’s face out of her mind, she drifted into troubled sleep.

(Part II)

#western#alt-history#horror#folk horror#writers of tumblr#writing community#writers on tumblr#my writing#writing#writeblr#novella#short story

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

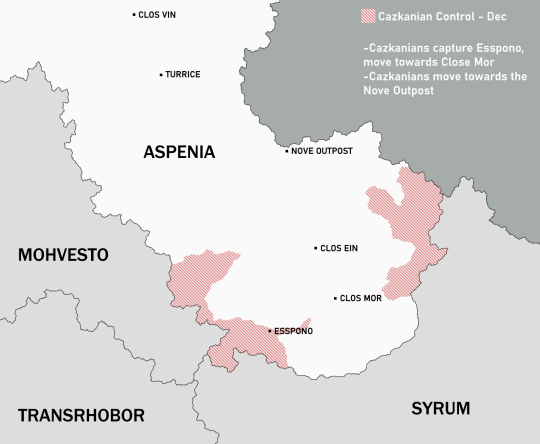

The Aspenian War, Aug 3, 160 - Mar 18, 161

This will be a big post with lots of images, but I'm excited to talk about this!

Though it only lasted for half a year, the Aspenia War as it came to be known had far-reaching and long-lasting consequences. These impacts would linger for years, even decades after the war concluded, and would add fuel to the growing flames of the political climate of 173 and the three-sided cold war Hessdalen found itself in.

This was southern Aspenia before the war began. Tensions had been growing with the Cazkanians for several years. Though they did not directly border each other, Cazkania controlled Mohvesto, Syrum, and Transrhobor as its satellites. From here it had been massing troops and equipment along the Aspenian border. Never believing they would actually attack, the Aspenians ignored this. Leaving them vulnerable.

The Cazkanians attacked in early August, storming border crossings and securing defensive positions in small towns and the few natural barriers the desert had to offer. The Aspenians went into full defensive mode until the country could properly mobilize, a task that would take precious time.

Also, until this point the TCA and Cazkanians had a shaky, but functional, relationship. In fact on August 3rd a joint scientific conference was underway in north-west Cazknaia with some of the alliance's best scientists and engineers in attendance. When news broke of an attack though, the TCA cut all talks with Cazkania and urged all of its citizens to return home. The conference ended abruptly and messily as all TCA nationals fled the country.

However, there were some who did not escape. These individuals, among them some children of the visiting scientists, were never heard from again. The Cazkanian government ignored all requests from the TCA for these people to be located, greatly contributing to the decline in relations.

By October the Cazkanians had made further gains, but by the end of Septemer the Aspenians had managed to ready themselves. They took a firm stand in Esspono as the city came under siege, and managed to push back the invaders in some locations. But unfortunately, for every step they took forward in one place, they took two more back in another.

October turned out to be a relatively successful month for the Aspenians. They continued to hold out in Esspono, and by November they had cut the western front in two and made significant gains in the northeast.

Unfortunately, time was weighing on the Aspenians by December. Esspono had fallen, and the Cazkanians were making a two sided charge for Clos Mor and the Nove Outpost. If Nove was captured, the key supply route from the core Aspenian territory to their forces on the front would be cut off.

The Cazkanians enacted a new goal that had formerly been considered too difficult: Taking Turrice. If they could capture the only crossing point of the Pelgriece canyon, the war in the south would be finished. So their forces move in from Mohvesto along the canyon.

Seeing the Cazkanian plan clearly, the Aspenians began to panic. Though they had been successful in defeating the first attack on Clos Mor, they knew if they lost Turrice that all would be lost. So they diverted more men to the new front.

The Aspenian army had a growing problem: morale. Their army was full of forced recruits, poor men from the lowest tiers of the caste system that were losing the small bit of connection they had to the country that ruled them as the war dragged on. The Cazkanians picked up on this and exploited it. Though their country was authoritarian and with few liberties, it was an improvement to the slavery of the Aspenian caste system.

The Aspenian soldiers began questioning their purpose, and if their enemy was really invaders... or liberators.

The Cazkanians captured Nove Outpost. And with it they cut off the easiest supply route for the Aspenians. With that, they began an onslaught that overwhelmed the Aspenians.

Desertion became rampant on the Aspenian lines, with many joining the Cazkanians after being subjected to their propaganda.

A group of Cethok fighters who knew the mountains well held out despite being cut off and even made some gains, but this was the only good news for Aspenia.

Despite being fought for every inch, the Cazkanians crawl towards Clos Ein and Turrice.

On March 18th, 161, Clos Ein fell to the Cazkanians. With this the Aspenians agreed to negotiate a peace, and were forced to give up every bit of their territory south of the Pelgriece canyon. This region became a Cazkanian puppet state that adopted Oretekism and completely abolished the caste system. And while the regime was oppressive, it was an improvement for the poor classes who came to see themselves as liberated. And so South Aspenia was born.

Aftermath

The Aspenian War had major consequences. It got exactly what Cazkania wanted, that being the final piece of their natural border wall. But this act of aggression on a peaceful nation, even though it was not a member state, led to the collapse of relations with the TCA, bringing the three-sided cold war into a new stage.

Most members of the highest Aspenian classes left the south before the Cazkanian forces could reach them, either moving to the north or abroad. Some landed in Rovaya, becoming important figures in that country's notorious shady side. Of those who did not leave, their property and wealth were stripped away, and they were integrated with those they used to subjugate.

Aspenia isolated itself from the world in humiliation, partly at least. The government was also afraid that the rest of their country would be exposed to the lure of "liberation" and demand they be freed of their caste as well. So the oligarchs made the desition to isolate from the world to protect their ancient system from a revolution.

The TCA was very vocal about the missing persons, with families wanting to find their loved ones again. But the Cazkanians would not grant a single response on the matter, and sadly as the years went by it became outshone by other matters in the TCA governments. Most families had given up hope by 173.

The historic trade corridor that was the Arch of Turrice was shut down to all traffic. At one time the land bridge over the canyon saw a constant flow of wealth cross it each day. But after the war it became desolate, and a point of interest in global geo-politics.

A Cazkanian Chief General was appointed to be the head of state of South Aspenia and direct the occupation. It was not difficult to integrate the majority into the Cazkanian sphere as they were given a better life under this new rule.

Today Aspenia remains divided, and unification is an idea far out of reach.

#worldbuilding#fantasy world#fictional world#writeblr#fictional history#writing#fantasy maps#imaginary maps#fantasy war#fantasy politics#cozar#oc lore

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Procession through streets returns Camp Pendleton Marine killed in rollover home to Riverside

First responders and community members in Riverside County gave a final salute to a 22-year-old local Marine who died in a vehicle rollover on a New Mexico road while on deployment to the United States border. Lance Cpl. Albert A. Aguilera of Riverside, a combat engineer with the 1st Marine Division at Camp Pendleton, was deployed as part of the Joint Task Force-Southern Border, the command…

0 notes

Text

New Mexico vehicle crash kills 2 US service members, leaves 1 in serious condition

Two U.S. service members are dead and another remains in serious condition after a crash on Tuesday near Santa Teresa, New Mexico. The three service members, deployed in support of Joint Task Force Southern Border, were involved in a “vehicle accident” at about 8:50 a.m. MDT near Santa Teresa, according to a news release from United States Northern Command (USNORTHCOM). Two were killed and one…

0 notes

Text

New Mexico Vehicle crash killed 2 US service members, left 1 in critical condition

Two -year -old members of the United States have died after an accident near Tuesday and the other is in critical condition Santa Teresa, New Mexico. Three service members deployed in support of the Joint Task Force Southern border, According to a report by the United States Northern Command (USNoarthCom), Santa Teresa was involved in a “vehicle accident” around the MDT at 50am: 50am. Two were…

0 notes

Text

A helicopter on a mission over the southern border near Rio Grande City, Texas, crashed on Friday, killing two National Guard soldiers and a Border Patrol agent.

A fourth soldier who was on board at the time of the crash was hurt and later listed in critical condition, the Associated Press (AP) reported Friday, noting officials were trying to determine the cause of the crash:

BREAKING: Per sources, there are “multiple fatalities” after a federalized National Guard helicopter w/ 3 National Guard soldiers working under federal Title 10 orders and a Border Patrol agent on board crashed in the RGV in La Grulla, TX this afternoon.

They were not working… pic.twitter.com/axsHqMXFwr

— Bill Melugin (@BillMelugin_) March 9, 2024

Joint Task Force North said the UH-72 Lakota helicopter was working with the federal government’s border security officials when the incident occurred.

When the crash occurred, Mexican cartel members were heard laughing in video footage taken near the scene, according to Fox News:

In video footage from a U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agent, obtained by Fox News, cartel members were seen watching the National Guards helicopter plummet to the ground with their drone.

…

The disturbing footage showed the moment the helicopter crashed, and the cartel members were seen dashing through the field in La Grulla, Texas.

“Go to he–,” the cartel members were heard yelling in Spanish.

Cartels frequent the La Grulla area where drug and human smuggling occur, the CBP agent explained

1 note

·

View note

Text

Exactly 30 years ago, a US F-16 recorded his first kill and also the first using an AIM-120 AMRAAM

Fernando Valduga By Fernando Valduga 12/27/2022 - 22:33 in Military, War Zones

General Gary North poses for a photo in front of the F-16 he was piloting when he shot down an Iraqi MiG-25.

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

On December 27, 1992, four U.S. Air Force F-16 fighters, led by Lieutenant Colonel Gary North, found an Iraqi MiG 25 that crossed the air exclusion zone in southern Iraq. The F-16 held the Iraqi aircraft in the air exclusion zone, preventing it from escaping north. One of the F-16s, arriving from the north, fired an AIM-120A against the Soviet-building fighter. Find out how this fight was.

In April 1991, shortly after the U.S. and its coalition allies expelled Iraqi military forces from Kuwait in Operation Desert Storm, the U.S. established an air exclusion zone in northern Iraq. This was soon followed by the establishment of a similar zone over southern Iraq to enforce United Nations Security Council Resolution 688.

This resolution guided the protection of Shiite Muslims against attacks by military forces under the control of Saddam Hussein, the Sunni Muslim dictator of Iraq, and a series of other sanctions. To support the resolution and protect the Shiites, the southern air exclusion zone covered the entire south of Iraq, from the 32-degree latitude line to the south to the borders of Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. The air exclusion zone applied to fixed and rotating wing aircraft, but in October 1991, the southern air exclusion zone also became a "d driving ban" zone and the U.S. Central Command Joint Task Force for Southeast Asia (JTF-SWA) was entrusted with the execution.

Lieutenant Colonel Gary North, commander of the 33rd FS; SSgt. Roy Murray, team chief; SA Steven Ely, assistant to the chief of the crew, pose with the F-16D #90-0778 that Lieutenant Colonel North was piloting when he shot down an Iraqi MiG-25 over the "No Fly Zone" on December 27, 1992. Mounted on the tips of the wings are the advanced medium-range air-to-air missiles AIM-120A. The location of this photo is at Shaw Air Base, on April 1, 1993.

Generally, most Southern Watch missions consisted of fighter scans and patrols, suppression of enemy air defenses, aerial reconnaissance and air command and control using AWACS E-3 Sentry aircraft.

However, the air operations conducted by Saddam Hussein's air force during 91-92 showed that he had no intention of complying with resolution 688. In fact, as explained by Donald J. McCarthy, Jr. in his book "The Raptors All F-15 and F-16 aerial combat victories", countless military combats between coalition forces and Iraqi command and control systems, anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) sites, radar sites and land-to-air missile sites (SAM) occurred since the end of the Gulf War in 1991 until the invasion of Iraq in 2003.

One of the most famous clashes took place on Sunday, December 27, 1992, when an Iraqi MiG-25 fighter (NATO name "Foxbat") violated the air exclusion zone and entered airspace south of the 33rd parallel.

U.S. Air Force Colonel Gary North undergoes pre-flight checks on F-16 Fighting Falcon aircraft before flying on a training mission at Luke Air Base in Arizona. The green star on the aircraft represents the Iraqi Mig-25 he shot down.

On that day, at approximately 10:42 a.m. local time, then captain Gary "Nordo" North (who piloted the F-16D "90-0778", indicative Benji 41) led a flight of four F-16s on a routine OSW Mission. While the Viper pilots were refueling from a KC-135, they heard urgent transmissions between a formation of four F-15s in the air exclusion zone and AWACS controllers. An Iraqi fighter (that F-15, having been close enough to obtain a visual acquisition, confirmed it as a "Foxbat") crossed the border to the air exclusion zone and was now accelerating north safely with the F-15 in pursuit. The Foxbat quickly reached the north of the 30th parallel and the F-15, now with little fuel, left the area.

As told by Craig Brown in his book "Debrief: a complete history of U.S. air engagements 1981 to the present", North and his wing refueled only enough fuel to allow them to cover the designated time at the station in the no-fly zone and crossed the border with southern Iraq while the third and fourth aircraft of their group continued to refuel. In a few minutes, the AWACS controllers ordered the two F-16s to head to an Iraqi aircraft heading south towards the thirty-two parallel to ensure that the Bogey did not cross to the air exclusion zone. A few minutes later, the AWACS controllers directed the Vipers to intercept another high-speed contact that originated in the north and crossed to the air exclusion zone approximately thirty miles west of the F-16 formation. The Iraqi fighter was forced to turn north safely before the F-16, armed with two advanced mid-range air-to-air missiles (AMRAAMs) AIM-120A and two AIM-9 Sidewinder missiles, could attack him.

MiG-25 of the Iraqi Air Force.

The AWACS radar monitored another aircraft, northeast of the F-16, flying south towards the air exclusion zone, but this time, while the F-16s flew to intercept the fighter, an Iraqi SAM radar began to track the Vipers. At this point, North ordered the third and fourth aircraft in his group, now fully charged with fuel, to fly north at their best speed. Again the AWACS radar reported a radar contact entering the air exclusion zone west of the Northern formation at high speed at 30,000 feet.

Bogey was flying directly to them from the east.

Nordo asked for a tactical displacement to the north to "fit" the F-16 between the MiG and parallel 30, creating a blocking maneuver and trapping the Iraqi fighter in prohibited airspace. The MiG could not escape back to Iraqi territory without fighting. "Someone would die in the next two minutes, and it wouldn't be me or my wing," North said.

North requested authorization to shoot by visually identifying the aircraft - a MiG-25 Foxbat armed with radar-guided AA-6 "Acrid" missiles. He instructed his ward to employ his electronic interference pod and again requested authorization to shoot. He finally heard "BANDIT-BANDIT-BANDIT, CLEARED TO KILL" about his headset. Approximately three nautical miles, fifteen degrees high from the nose and fifteen degrees from the right bank to the north, he blocked the MiG-25 and fired an AMRAAM, which led to the impact and totally destroyed the Foxbat built in Russia.

It took less than 15 minutes from the moment North left the KC-135 to shoot down the MiG. The video below is the original footage of the slaughter described in this article.

youtube

On October 28, 1998, Colonel Paul "PK" White interviewed North for an article of his own, "Nordos' MiG Kill", where North described the moment of the missile's impact: "I saw three separate detonations, the nose and left wing broke instantly and the tail continued in the main body of the jet and, finally, a huge fireball."

Noteworthy, this fight marked not only the first aerial victory won by an American F-16, but also the first shooting of an AIM-120 AMRAAM.

Tags: Military AviationF-16 Fighting FalconHISTORYIqAF - Iraqi Air Force / Iraqi Air ForceUSAF - United States Air Force / US Air ForceWar Zones - Iraq

Sharing

tweet

Pin

Fernando Valduga

Fernando Valduga

Aviation photographer and pilot since 1992, he has participated in several events and air operations, such as Cruzex, AirVenture, Dayton Airshow and FIDAE. He has works published in specialized aviation magazines in Brazil and abroad. Uses Canon equipment during his photographic work in the world of aviation.

Related news

HISTORY

VIDEO: The 10 most UFO-like planes

11/01/2023 - 18:03

MILITARY

Elbit Systems receives contract to provide new Mission Training Center for Israeli F-16s

11/01/2023 - 14:00

MILITARY

Dassault resumes deliveries of Rafales to the French Air Force

11/01/2023 - 13:00

MILITARY

IMAGES: Indian Su-30MKI jets land in Japan for bilateral exercise

11/01/2023 - 08:30

An F-35A flying over the Mojave Desert, California, on January 6, 2023.

MILITARY

Fly the first F-35 fighter with TR-3 update

10/01/2023 - 22:25

MILITARY

Irish Air Force acquires average transportation aircraft, probably an Airbus C295

10/01/2023 - 16:00

Cavok Twitter

homeMain PageEditorialsINFORMATIONeventsCooperateSpecialitiesadvertiseabout

Cavok Brazil - Digital Tchê Web Creation

Commercial

Executive

Helicopters

HISTORY

Military

Brazilian Air Force

Space

Specialities

Cavok Brazil - Digital Tchê Web Creation

10 notes

·

View notes

Link

The 2020 Democratic presidential campaign has been surprisingly promising when it comes to addressing poverty. Candidates have offered a host of ideas that would have a significant anti-poverty effect, from universal health care to debt-free college, a living wage, housing for all, universal child care, and more. They have also pledged to push for a debate focused exclusively on the issue—a promise they still need to make good on. But one region that hasn’t received the attention it needs in this or previous elections is the rural Black Belt, specifically the persistently poor counties in 11 Southern states that are home to more than half of the nation’s non-metro poor.

The name “Black Belt” originally referred to the region’s dark, clay soil, before eventually coming to signify its high population of African Americans as well. Today, the region’s roughly 300 rural counties—in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia—each have populations that are between 30 and 80 percent African American. As of 2008, the Black Belt was home to 83 percent of African Americans living outside metropolitan areas. We’re just two weeks away from the South Carolina Democratic primary, on February 29; six more Black Belt states will vote on March 3. It’s time for a presidential candidate to not only engage with the needs of people living in this region but also begin to rectify a history of exploitation and neglect.

There is precedent for it: then-Senator John F. Kennedy’s visit to West Virginia during the 1960 Democratic primary. As Ronald D. Eller describes in his 2008 book Uneven Ground, Kennedy was “genuinely stunned” at the mass poverty he saw, particularly that of unemployed coal miners. He pledged on camera to introduce an aid program for the state if elected—and, after he was, he created a presidential task force to explore a unique federal-state-local partnership for regional development in Appalachia. The task force outlined a program that would support highway construction, health care facilities, land stabilization, timber development, water facilities and sewer treatment, and vocational training. But it would take until 1965 for President Lyndon B. Johnson to succeed in pushing it through Congress, establishing the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC).

Since then, the ARC has received a total of $38 billion in federal funding (adjusted for inflation), benefiting counties across 13 states. While Appalachia still faces challenges such as labor force participation and poor access to health care, the ARC has contributed to largely eliminating the gap between the region’s rates of high school graduation and unemployment and those found nationally. It has helped both to cut Appalachian poverty from 31 to around 17 percent, and to lower the number of high-poverty counties in the region, from 295 to 107.

The idea for a corresponding regional development program in the Black Belt isn’t a new one. Scholars at Southern universities and some politicians—including Democratic US Representative (2003–11) Artur Davis of Alabama and the late Senator (2000–05) Zell Miller of Georgia—have pushed for it since the 1990s. The black rural South’s current unemployment rate of approximately 14 percent and child poverty rate of 51 percent are double those found in rural counties included in the ARC, according to a forthcoming paper from the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies.

“I’ve heard it my whole life: ‘There’s nothing in the Black Belt.’ Are you kidding me?” says Dr. Veronica Womack, a Black Belt native and executive director of the Rural Studies Institute at Georgia College and State University. “This is a region where the people have always made a way out of no way. You can’t find any more hardworking, caring people—people who have continued to raise families, build community, go to church on Sundays, in spite of all of the challenges that have been put in place.” What has been lacking, Womack says, is a commitment to the region so people can “operate at their fullest potential.”

There have been piecemeal legislative efforts to increase the flow of investment to parts of the Black Belt. But none include all 11 states, focus exclusively on Black Belt counties, or—critically—prioritize community participation in designing and leading a commission to address the Black Belt’s unique challenges. “If you understand the tenacity and the resilience of the people who live there, then you understand the importance of them being a part of whatever solutions you have,” Womack says. “The commission has to know the history—the social, political, and economic dynamics of the place and space.”

In 2000, the Delta Regional Authority (DRA) was created as a state-federal partnership that is presided over by eight Southern state governors and a federal cochair. It includes some counties in five Black Belt states and received $25 million for fiscal year 2019. Seventy-five percent of the moneys are supposed to go to distressed counties, and half of those are required to be used on transportation and infrastructure. However, it does not include most of the Black Belt, and none of its board members are African American. It also lacks the community participation and leadership element that Womack says is key.

Arguably the most promising effort was the Southeast Crescent Regional Commission (SCRC), created under the 2008 Farm Bill. Modeled after the ARC, it encompassed counties within seven Black Belt states, and was intended to focus on funding distressed communities for transportation, infrastructure, job training and entrepreneurial development, telecommunications, and sustainable energy solutions. However, while the SCRC was authorized to receive at least $30 million every year through 2019, it was never appropriated more than $250,000 at a time, and “does not appear to be active” as of March 2019, according to the Congressional Research Service. In contrast, the Northern Border Regional Commission—created in the same Farm Bill to address economic hardship in the primarily white populations of northern Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, and New York—has received steady funding, including $10 million to $20 million in each of the past three fiscal years.

The SCRC was championed by the Democratic Representatives Hank Johnson of Georgia and Elaine Luria of Virginia, as well as majority whip James Clyburn, of South Carolina. “Congressman Clyburn has been committed to the SCRC since its inception,” says Hope Derrick, his communications director. “[He] is ready to fight for more funding when the administration appoints a federal cochair, the last hurdle in standing up the commission.”

Womack isn’t surprised by the lack of urgency the SCRC or Black Belt Commission proposals have received from most of the political elite. “When you start talking about policy that will be interpreted as benefiting a region significantly [comprising] black people, then where is the will to actually get that done?” she says. “Even though the Black Belt has all kinds of people in it, there is also a particular combination that our country has had a great difficulty addressing: poor people, and then poor people of color, and then poor black people.”

The need for a commission focused exclusively on the rural Black Belt is most apparent in places like Lowndes County, Alabama, where people are living with raw sewage in their yards.

Lowndes County is located between Selma and Montgomery, and every year tourists pass through, following the route of the historic 1965 civil rights march led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Mostly made up of small rural communities, it has a declining population of under 10,000 people, of whom more than 72 percent are African American. Residents here struggle against the soil that gave the Black Belt its name and made Alabama’s cotton king: Water can’t percolate smoothly through the chalky clay. Traditional septic tanks don’t work there; plumbing backs up when it rains, sending wastewater back into homes through sinks, tubs, and toilets.

The median household income in Lowndes County is $28,000 a year—and the kind of tank that residents would need can cost up to $30,000 for purchase and installation. Some residents resort to “straight piping,” which involves running a PVC pipe away from the home and into the yard, where it discharges untreated waste. As a result of not having affordable waste treatment, families have no choice but to contaminate their own properties. A 2017 study of Lowndes County residents by the Baylor College of Medicine found that 34.5 percent tested positive for hookworm, an intestinal parasite associated with the developing world. After the UN’s special rapporteur on extreme poverty visited homes in Lowndes County and nearby Butler County, he described the waste crisis as “very uncommon in the first world…. I’d have to say that I haven’t seen this.”

“You can say all day long that [people] ought to just move, but [they] are born and raised here,” says Lenice Emanuel, executive director of the nonprofit organization Alabama Institute for Social Justice, who has worked with residents on this issue. “They don’t have the money to just uproot their lives and move to Montgomery 25 miles away. Then you have a transportation issue too—getting back and forth to their jobs,” since many work in the community. She also notes that there are businesses—most of which, advocates say, are white-owned—that do have the necessary infrastructure in place to treat their waste, just a half-mile away from homes dealing with raw sewage. Engineers say that simply expanding municipal sewer lines could help solve the problem for some Black Belt homes. For that, the County would need funding.

According to Emanuel, when county residents have invited state officials to come and witness the conditions firsthand, they have been subjected to “intimidation tactics” such as being threatened with arrest warrants, or even fined for lacking septic tanks they could not afford. These reactions from the state have also made it more difficult for residents to feel sufficiently safe to organize and advocate for change. While Alabama says it stopped issuing arrest warrants for sewage in 2002, a black pastor was arrested as recently as 2014 because a septic tank failed and his church wasn’t able to deal with the overflow. Emanuel says that the damage of past warrants is already done: Many people who received them now have a criminal record, and some have lost or can’t find jobs as a result.

Emanuel draws an analogy between the way people are being treated over the waste issue and the KKK’s showing up in their communities—“I liken it to that kind of terror.” She says it leaves people feeling “helpless” and “at the mercy of the institutions and power structures in the community. And it’s similar all over [Alabama’s] Black Belt counties.”

Alabama Democratic representative Terri Sewell sponsored the Rural Septic Tank Access Act—which passed in the 2018 Farm Bill—to help her constituents in Lowndes County and other rural areas access grants of up to $15,000 to install or maintain wastewater systems. This is still significantly lower than the cost of appropriate septic tanks in many homes. An aide to Sewell says she is working to increase the resources devoted to the issue, including the maximum allowable grant.

It can also be difficult for Black Belt communities to navigate the federal protocols to obtain funds—in part, Womack says, because these local governments just don’t have the staff to work on chasing grants. Case in point: Lowndes County is actually eligible for Delta Regional Authority funding, but if you look at the DRA’s most recent grants for infrastructure in Alabama Black Belt communities, the county with sanitation conditions comparable to the Third World is nowhere to be found. In contrast, the DRA did provide $509,000 to extend an industrial park’s water and sewer system to serve Enviva, the world’s largest wood pellet producer.

When Kennedy visited West Virginia in 1960, poverty in the region was stark: 33 percent of Appalachian families lived in poverty, compared to a national poverty rate of 20 percent; unemployment was 40 percent higher than the US average. Many more workers had given up on finding a job and left the workforce. That year, the Conference of Appalachian Governors declared that underdevelopment had meant that people in the region were “denied reasonable economic and cultural opportunities through no fault of their own.” Moreover, inadequate infrastructure for things like “transportation and water resources [had] hindered the local ability to support necessary public services and private enterprise.”

“The ARC is reparations,” says Spencer Overton, the president of the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies. He says that in the coming months, the Joint Center will release a proposal for a Black Belt Regional Commission, hoping to address “an area of our country that once required a large number of people to work there. Those places became automated over time, but large populations are still there and there are fewer jobs. And so we have to come up with policy solutions. That’s the case when we talk about Appalachia; that’s the case when we talk about the Black Belt.”

Kennedy may have advocated for the ARC, in part, because he needed to win over West Virginia voters in the primary. As Michael Bradshaw describes in his 1992 book about the ARC, the senator’s visit to Appalachia came at a key moment in the campaign, when his challenger already had the support of organized labor. Kennedy announced his pledge for a state development program on the day before the vote. He had discussed black Southerners’ struggles during his campaign, but the fact that Appalachia was associated with white poverty made the program politically palatable to white voters and politicians.

Overton points to Appalachia and the Black Belt’s parallel histories of exploitation and resource extraction. In the case of the Black Belt, he says, it has been about “profiting off of cheap labor—whether that is slavery, Jim Crow, or the factories with low taxes, cheap wages, and no unions. Recognizing the unique history and consequent struggles in Appalachia, but not in the Black Belt, is like saying we’re going to treat the opioid crisis as a health epidemic, but we’re going to use the criminal code to deal with the crack epidemic.”

Andy Brack, former press secretary for the late South Carolina Democratic Senator Ernest Hollings and a longtime journalist and editor covering Southern politics, has no doubt as to the root of the structural inequality we see in the Black Belt today. In a 2013 piece, he compared a map showing deep poverty rates with a map of slavery in 1860: “With the blink of an eye, it’s easy to see that these areas easily correlate with where enslaved people lived in 1860. The [Black Belt] is a remnant of plantation life…. One hundred and fifty years after the Civil War, it’s time that this area starts receiving the same attention that Appalachia did.”

Researchers with the Southern Economic Advancement Project (SEAP)—an initiative founded by Stacey Abrams that focuses on policy solutions and capacity-building for vulnerable populations in the South—recently embarked on a listening tour in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and North Carolina. (SEAP is a fiscally sponsored project of the Roosevelt Institute, where I am a journalist-in-residence.) As they spoke with nonprofits and grassroots groups to get a better sense of local challenges, there were some consistent concerns, including a lack of access to transportation, struggles with raw sewage and other environmental issues, and lack of investment from banks. One participant noted the “weight of racism”—as seen in housing separated by race, resegregated schools, and uneven development between predominately white and predominately black areas. Multiple groups cited the challenge of stigma, from outsiders who viewed their communities as hopeless and lacking potential.

Dr. Sarah Beth Gehl, SEAP’s research director, says that in western North Carolina and northern Alabama, which both have ARC funding-eligible counties, the local-state-federal partnership came up repeatedly—for example, for supporting children’s services, local government capacity-building, and transportation for those in addiction recovery. But when SEAP traveled to south Georgia or south Alabama, where counties aren’t covered by the ARC, the conversations were very different. “It was a lot about a lack of resources and a lack of attention,” says Gehl. “The infrastructure needed to take some innovative approaches to tackling deep challenges in these Black Belt communities—that piece was missing.” Moreover, when it came to what some people on the tour called “the basics needed for a dignified life”—like a grocery store, transportation, housing stock, or medical facilities—the resources just weren’t there.

“Economic progress for the Black Belt requires innovation and deep commitment, which means providing consistent investment to address the interconnected issues that hinder growth and block equity,” says Abrams in a statement to The Nation. “Funding the Black Belt Regional Commission would be a declaration of real intent to finally serve this Southern arc, and it is long overdue.”

It is easy to imagine the arguments against a Black Belt Regional Commission that would be loosely based on the ARC. If there is still extensive poverty in Appalachia, why would we repeat the model? But the ARC has had an enormous impact. In the 2018 fiscal year alone, it reported that its investments would create or help retain more than 26,600 jobs, and train and educate more than 34,000 students and workers. The ARC’s $125 million investment was matched by $188.7 million in public and other moneys, and is expected to attract over $1 billion in private investments.

There are ways too that a Black Belt Commission could be done differently. The ARC covers a huge region, including areas that do not suffer from persistent widespread poverty; funds are weighted toward distressed areas, but the appropriated money is inadequate to cover that expanse. A Black Belt Commission could focus exclusively on distressed communities. Also, much of the early ARC money was spent on highway construction through Appalachia—which, as Michael Bradshaw writes, the original ARC director felt was necessary in order to connect poorer economies with wealthier ones. (He also thought it would show legislators “results.”) While infrastructure is vital, a Black Belt Regional Commission could equally emphasize investment in people—their health, education, training, and the creation of jobs that would allow for upward mobility.

Dr. Veronica Womack says she would start with education—from early childhood to higher education—as well as infrastructure development, including for broadband Internet access, investment in start-ups and rural entrepreneurships, and rural health services for people who currently live in “health care deserts.”

“That’s just a start. Because if you’re not healthy, or you don’t have the proper education and training, the likelihood of you being successful in the 21st century is very small,” she says.

Spencer agrees. “Too often, there has been the notion that economic development is attracting a poultry processing plant—very hard, low-wage, unattractive work without a lot of prospects for growth,” he says. “We need to invest in human beings. It gets back to the concept of Black Lives Matter: We really want to recognize the humanity of people, and invest in people so they can achieve their potential.”

In addition to having local elected officials at the table, Womack says a commission should include community-based organizations that have been working in the region for decades, such as the Black Belt Community Foundation, the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, Southwest Georgia Project, and other similarly focused organizations “connected to agriculture and the land—a big piece of how we can be sustainable.” She would also want to invite historically black colleges and universities, technical and community colleges, and land grant and rural institutions such as Georgia College and State University that “understand rural places and are working in the region already.” Crucially, the commission should also hear from activists who are not attached to any particular organization, Womack says, because “the people in their community look to them and their leadership.”

“These folks can tell you exactly where the hiccups are—where the challenges and barriers lie in their being able to develop their communities,” says Womack. “And so, if we are going to hit the mark, it’s going to require us to do a different type of policy and a different type of policy implementation that doesn’t block off people from even being able to participate in the decision-making.”

Yet none of this will be possible without presidential leadership—the kind Kennedy embraced when he visited poverty-stricken areas in West Virginia.

Bernie Sanders, who has called poverty a death sentence, visited Lowndes County last May and pledged to a resident, “This is just the beginning. We have to get attention to the issue, and then we’ll do something about it.” That resident, Pamela Rush, also spoke at a forum on poverty convened by Elijah Cummings and Elizabeth Warren in 2018. Pete Buttigieg noted at one of the debates that poverty hadn’t come up, and that “it deserves a lot of attention”; both he and Amy Klobuchar have struggled to win over black voters. And while Joe Biden has touted his poll numbers with African Americans, he has struggled to connect with younger generations, many of whom feel he falls short in addressing systemic issues.

If any of these or other candidates spend more time in the Black Belt, will they offer so bold a proposal as a Black Belt Regional Commission? Or will they ignore the generational poverty and continued isolation of the region?

Lenice Emanuel says that elected leaders need to take stock of how they are serving, or failing to serve, the people of the region. “We have got to look inward at our own culpability in maintaining these systems of inequity,” she says. “We have to be real with ourselves about that. That’s where the answer lies.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Britain’s seven covert wars: An Explainer

Published: Daily Maverick (17 September 2019) w/ Mark Curtis

The United Kingdom is fighting at least seven covert wars largely outside parliamentary or democratic oversight.

The British government states that its policy on the covert wars it fights is “not to comment, and to dissuade others from commenting or speculating, about the operational activities of special forces because of the security implications”.

The British public’s ability to scrutinise policy is further restricted by the UK’s Freedom of Information Act which applies an “absolute exemption” to its special forces.

UK special forces consist of a number of regiments, but the Special Air Service (SAS), a unit of the British army, is the most renowned. Based at RAF Credenhill, just outside Hereford in western England, it is rumoured to have about 500 personnel.

This explainer outlines what is known of these covert wars, which is likely to represent only a small part of actual UK military operations in these countries. Nearly all the leaks which appear in the mainstream media are officially sanctioned and have been further approved by the Ministry of Defence’s DSMA Committee, which seeks to prevent material deemed damaging to the national security interest from being published in the media.

Afghanistan

The SAS has fought in Afghanistan since 2001, longer than any war in the regiment’s history, according to some sources.

The public was told at the end of 2014 that British forces had withdrawn from Afghanistan. However, some British troops stayed behind to help create and train an Afghan special forces unit. Despite officially only having “advisers” in the country, British covert forces have consistently fought Islamic State and the Taliban.

By 2018, the SAS was reportedly fighting almost every day in Afghanistan, usually in support of Afghan commandos leading the battle against the Taliban.

In February 2018, Britain doubled the size of its SAS force in Afghanistan from about 50 to more than 100. One newspaper reported at the time:

“The commandos will conduct kill-or-capture missions alongside US special forces and come under the command of the American-led Joint Special Operations Command. Part of the force will be made up of 15 snipers who will be part of a specialist unit tasked with killing Taliban commanders.”

In July 2018, “dozens” more special forces troops were sent to Afghanistan as part of a contingent of 490 extra soldiers deployed to join the almost 650 already there.

By March 2019, the Pentagon was asking British special forces to play a key role in counter-terrorist operations in Afghanistan. This followed US President Donald Trump’s decision to pull US troops out of the country. It was also reported that a contingent of the Special Boat Service (SBS) is operating in central and eastern Afghanistan.

In 2014, the government stated that it had ended its drone strikes programme in Afghanistan, which had begun in 2008 and covered much of the country. It is believed that all British Reaper drones were withdrawn from Afghanistan by the end of 2014. Yet in 2015, British special forces were still calling in airstrikes using US drones instead.

Overall, British troops in Afghanistan numbered about 1,000 by mid-2019.

Iraq

Hundreds of British troops have been deployed in Iraq to train local security forces. But they are also engaged in covert combat operations against Islamic State.

In early 2016, Britain reportedly had more than 200 special forces soldiers in the country, operating out of a fortified base within a Kurdish Peshmerga camp near Mosul in northern Iraq. In May 2016, special forces were given the green light to conduct covert parachute assaults involving SAS and SBS commandos being sent in to support Kurdish and Iraqi troops fighting Islamic State, with small vehicles, heavy machine guns and mortars.

The SAS in Iraq was also reported in 2016 to have been given a “kill or capture” list of up to 200 UK citizens who had joined the Islamic State group.

By May 2019 about 30 SAS and SBS troops were reported to be working on a “kill or capture” mission to hunt down Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in Iraq. They were said to be operating from a special forces HQ north of Baghdad and teaming up with US special forces. The search for al-Baghdadi reportedly involved MI6, UK listening station GCHQ and the American National Security Agency.

British Reaper drones were first deployed over Iraq in 2014 and continue to fly. From then until March 2019, UK drones conducted 1,384 missions in Iraq, releasing 666 weapons.

Libya

SAS forces were secretly deployed to Libya at the beginning of 2016, working with Jordanian special forces embedded in the British contingent. This followed a mission by MI6 and the Royal Air Force in January 2016 to gather intelligence on Islamic State and draw up potential targets for airstrikes.

Some 100 British special forces were said to be operating in Libya in early 2016, helping to protect government officials and advising Libyan forces on fighting Islamic State. The Libyan Express reportedthat “British and American intelligence officers ‘with suitcases full of cash’ are bribing tribal leaders not to oppose an international ground force” in the country.

British commandos were soon also engaged in fighting and directing assaults against Islamic State in Libya. They also ran intelligence, surveillance and logistical support operations from a base in the western city of Misrata.

A team of 15 British special forces were also reported in June 2016 to be based in a French-led multinational military operations centre in Benghazi, eastern Libya, supporting Libyan general Khalifa Haftar. In July 2016, Middle East Eye reported that this British involvement was intended to help coordinate airstrikes in support of Haftar, whose forces are opposed to the Tripoli-based government that Britain is otherwise supporting. It was unclear why.

In 2017, eight members of the SBS — supported by 40 British specialists — were deployed with US, French and Italian forces “to deny Islamic State any opportunity to establish a base in Libya”.

A Libyan anti-terrorism official was quoted as saying in May 2019 that the UK was co-operating with the Libyan government in “surveilling and fighting terrorists”. In the same month, an SAS unit was evacuatedby the RAF following the rapid advance of Haftar’s forces in the cities of Tobruk and Tripoli.

Pakistan

The UK has been a co-party to the US’s extensive drone campaign in Pakistan. The UK spy base at Menwith Hill in Yorkshire has facilitated US drone strikes against jihadists in Pakistan, with Britain’s GCHQ providing “locational intelligence” to US forces for use in these attacks.

RAF pilots at Creech Air Force Base in Nevada have been involved in these US drone operations in Pakistan (and Afghanistan) which have killed hundreds of civilians. The role of these pilots is unclear but, Amnesty International notes, “this does raise concerns that UK pilots under US command may have been ordered to carry out drone strikes and could therefore implicate them in these violations”.

US drone strikes continue in Pakistan, although at much lower levels than in previous years, and the UK role in them remains obscure.

Somalia

A small contingent of SAS troops has been training and advising Kenyan security forces and providing intelligence to help Kenya in its efforts against al-Shabaab in Somalia, including to capture its leaders.

In 2012, it was reported that the SAS was working on the ground in Somalia with Kenyan forces to target al-Shabaab terrorists. This involved up to 60 SAS soldiers, close to a full squadron, including forward air controllers who called in airstrikes by the Kenyan air force, which also employs a number of ex-RAF pilots.

In early 2016, Jordan’s King Abdullah, whose troops have operated with UK special forces for the war against Bashar Assad in Syria and whose special forces were planned to be embedded with the UK’s in Libya, said that his troops were also ready with Britain and Kenya to go “over the border” to attack al-Shabaab in Somalia.

By April 2016 it was reported that the SAS had a 10-strong team in Somalia, based at a camp north of Mogadishu, which was engaged in “regular skirmishes” with al-Shabaab and was also training Somali soldiers. The SAS team was also working with US Delta Force directing airstrikes against the insurgents by US jets based in Djibouti.

The British government said in May 2016 that it had 27 military personnel in Somalia. These troops were said to be supporting the UN, EU and African Union training missions in Somalia which were set up to counter al-Shabaab and were “developing” the Somali national army.

The Menwith Hill base in Yorkshire has also facilitated US drone strikes against jihadists in Somalia (as they have in Pakistan), with Britain’s GCHQ similarly providing “locational intelligence” to US forces for use in these attacks.

Syria

Evidence suggests that a British covert operation in Syria began in late 2011. By November of that year, MI6 and French special forces were reportedly assisting Syrian fighters and assessing their training, weapons and communications needs. The CIA, meanwhile, was providing communications equipment and intelligence.

Britain also became involved in the “rat line” of weapons delivered from Libya to Syria via southern Turkey. This was authorised in early 2012 following a secret agreement between the US and Turkey. Revealed by journalist Seymour Hersh, the project was funded by Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar while “the CIA, with the support of MI6, was responsible for getting arms from Gaddafi’s arsenals into Syria”.

British and US covert operations were focused on toppling the Assad regime in the first few years of the war. Britain began training Syrian rebel forces fighting Assad from bases in Jordan in 2012. At the same time, the SAS and SBS also began “slipping into Syria on missions”.

No evidence appears to have emerged of British training of Syrian rebels to fight Islamic State in Syria before May 2015, when Britain sent 85 troops to Turkey and Jordan to train rebels to fight both Islamic State and Assad. By July 2015, Britain was training Syrians in Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Jordan and Qatar to fight Islamic State, but the war against Assad also continued. As part of a US-led training programme, British special forces provided training, weapons and other equipment to the New Syrian Army, comprised of defectors from the Syrian army.

In 2015, British special forces were “mounting hit-and-run raids against Islamic State deep inside eastern Syria dressed as insurgent fighters”. They were reported to “frequently cross into Syria to assist the New Syrian Army”, from their base in Jordan.

Turkey also offered a base for British military training. In 2015, for example, Britain deployed several military trainers to Turkey as part of the US-led training programme in Syria. This programme was providing small arms, infantry tactics and medical training to rebel forces.

British aircraft began covert strikes against Islamic State targets in Syria in 2015, months before Parliament voted in favour of overt action in December 2015. These strikes were conducted by British pilots embedded with US and Canadian forces.

In September 2016, UK forces were involved in US-led airstrikes against targets in Syria which killed more than 60 Syrian troops. These strikes were part of a battle against Islamic State in Deir Ezzor in eastern Syria which the US and UK claimed they were targeting and had hit Syrian army targets accidentally. In June 2018, the RAF targeted Syrian army forces near the border with Iraq and Jordan in close proximity to a UK/US special forces base.

Some 200 UK troops were in Syria in early 2018, consisting of the SAS, Parachute Regiment and Royal Marines which together make up the Special Forces Support Group. They were working alongside the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces.

In March 2018, Matt Tonroe, an SAS soldier embedded with US forces, was killed in the northern city of Manbij, fighting with local Kurdish troops against Islamic State. SAS sources claimed that those who planted the bomb which killed Tonroe could have belonged to the Free Syrian Army. However, a media investigation in 2019 revealed that Tonroe was killed by “friendly forces” after an accidental detonation.

British special forces continue to operate on the ground in Syria in 2019 and are reported to number at least 120 soldiers.

Britain has also been operating a secret drone warfare programme in Syria which began in 2014. From then until March 2019, UK drones conducted 1,801 missions in Syria, releasing 304 weapons. In 2017, Reaper drones killed two British Islamic State militants in Syria, again before parliament approved military action.

Yemen

The government previously claimed it had no military personnel based in Yemen. Yet a Vice News report in 2016 based on interviews with UK officials revealed that British special forces were in Yemen. They were, in fact, seconded to MI6, which was training Yemeni troops fighting Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and had infiltrated AQAP.

Vice News also revealed in 2016 that British military personnel were helping with US drone strikes against AQAP. Britain was playing “a crucial and sustained role with the CIA in finding and fixing targets, assessing the effect of strikes and training Yemeni intelligence agencies to locate and identify targets for the US drone programme”. UK officials, the report said, were taking part in “hits”, preparing “target packages” and participating in a “joint operations room” with US and Yemeni forces in support of strikes.

The Menwith Hill base in Yorkshire facilitates US drone strikes in Yemen, as shown in files from Edward Snowden revealed by The Intercept in 2016. Documents show that the US National Security Agency has pioneered groundbreaking new spying programmes at Menwith Hill to pinpoint the locations of suspected terrorists accessing the internet in remote parts of the world. This role for Menwith Hill was denied for years by the UK government.

In November 2017, it was revealed that the British Army was secretly training Saudi troops to fight in Yemen. It was reported that up to 50 UK military personnel were in Saudi Arabia teaching battlefield skills. The training mission — codenamed Operation Crossways — came to light only after the army released photos and information by mistake. The training was undertaken by UK troops from the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Regiment of Scotland who were imparting “irregular warfare” techniques to officers from the Royal Saudi Land Forces Infantry Institute.

In January 2019, a 12-man US/UK special forces task force, comprising the SAS and the US Green Berets, was flown into Yemen from Djibouti. The soldiers were dressed in Arab clothing and were reported to be operating near the government-held town of Marib, 500 miles north of Aden.

By March 2019, 30 SBS personnel were deployed inside Yemen, based in the Sa’dah area of the northern part of the country. The SBS force includes medics, interpreters and intelligence officers and their mission is to “advise” official Saudi and Yemeni government troops. However, the media has reported that these SBS forces have also been involved in fierce clashes with militia groups. An SBS spokesperson has said that British soldiers have been injured in “firefights”.

More on the UK’s drone wars

The UK has been recently involved in drone strikes in at least six countries: Afghanistan,Iraq, Pakistan, Somalia, Syria and Yemen. Its squadron of 10 Reaper drones is controlledremotely by satellite from RAF Waddington in Lincolnshire and by RAF aircrew at Creech Air Force Base in Nevada, US.

The RAF’s secret drone war beganin Afghanistan in October 2007 and elsewherein 2014. The NGO Reprieve notesthat Britain provides communications networks to the CIA “without which the US would not be able to operate this programme”. Reprieve says that this is a particular matter of concern as the US covert drone programme is illegal.

UK personnel have been embeddedwithin US units and form part of US drone operations. UK personnel flew US drones (Predators) during Operation Ellamy, the codename for the UK’s participation in the military intervention in Libya in 2011. UK personnel embedded with the US Air Force have also operated US armed and unarmed drones in Afghanistan and Iraq.

In July 2018, a two-year probe by the All Party Parliamentary Group on Drones revealedthat the number of drone operations facilitated by the UK in Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Pakistan and Somalia has been growing without any public scrutiny. The drone strategy also involved working with repressive regimes including the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Qatar.

Amnesty International’s 2018 report, Deadly Assistance, documented four RAF bases in the UK involved in the US drone attacks programme: Menwith Hill in Yorkshire, Molesworth in Cambridgeshire, Digby in Lincolnshire and Croughton in Northamptonshire. Around one-third of all US military communications in Europe pass through RAF Croughton, which has a direct link through a fibre-optic communications system to a US military base in Djibouti (Camp Lemonnier), from where most US drone strikes in Yemen and Somalia are carried out.

Embedded in the US and other militaries

The government stated in 2015 that it had 177 military personnel embedded in other countries’ forces. Some 30 of those were working with the US military. UK military personnel are assignedto various commands in the US and to US Navy Carrier Strike Groups.

It is possible that these forces are also engaged in combat. For example, the then First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Philip Jones, saidBritish pilots fly US F18s from the decks of US aircraft carriers in the Gulf. This means that some “US” airstrikes may well be carried out by British pilots.

“British forces embedded in the armed forces of other nations operate as if they were the host nation’s personnel, under that nation’s chain of command”, the Ministry of Defence has stated.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

We got this from our Austin office this morning for public release. So before people start freaking out about what's going on in Texas this weekend here you go.

FYI – For Information and situational awareness. Please forward as you see fit.

October 25, 2018 NEWS RELEASE

FBI and DPS Lead Statewide Full-Scale Training Exercise

AUSTIN – The four Texas Divisions of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (Dallas, El Paso, Houston and San Antonio) and the Texas Department of Public Safety will lead a statewide Full-Scale Training Exercise (FTX) beginning Sunday, Oct. 28, at noon and ending at approximately 5 p.m. Tuesday, Oct. 30.

Numerous local, state and federal agencies* will participate in several FTX sites throughout Texas – in the cities of Greenville, Brenham, San Antonio and El Paso. The FTX will examine the ability of federal, state, local, tribal and territorial jurisdictions to respond to complex terrorist attacks with a focus on integrated response planning among law enforcement, medical services, emergency management and other whole community stakeholders.

Texans should not be alarmed if they see a large number of law enforcement personnel and equipment throughout the state during the exercise. We ask the public to avoid areas where the FTX is taking place — where out of the ordinary activity may occur related to the exercise, including role players portraying attackers and victims. (Additional details regarding specific FTX locations will be forthcoming from the respective FBI Division Offices.)

During the FTX, participants will focus on enhancing their ability to respond to real-life crisis events in an effort to save lives. Texans are reminded of the important role they also play in ensuring the safety of our communities by always reporting suspicious activities to law enforcement.

*Exercise participants include:

State of Texas

Select Texas Emergency Management Council Departments and Agencies

Texas Army National Guard

Texas Department of Public Safety

Fusion Centers

Multi-Agency Tactical Response Information eXchange (MATRIX)

North Texas Fusion Center

Southwest Texas Fusion Center

Texas Joint Crime Information Center

Local Agencies and Entities

Bexar County Sheriff’s Department

Blinn College Police Department

Brenham Police Department

City of El Paso – Department of Public Health

City of San Antonio Office of Emergency Management

El Paso City/County Office of Emergency Management

El Paso County Sheriff’s Office

El Paso Fire Department

El Paso International Airport

El Paso Medical Examiner’s Office

El Paso Police Department

Garland Police Department

Greenville Fire Department

Greenville Police Department

Hunt County Emergency Medical Services

Hunt County Sheriff’s Office

Pebble Hills High School

San Antonio Fire Department

San Antonio International Airport

San Antonio Police Department

The University of Texas at El Paso

Washington County Office of Emergency Management

Washington County Sheriff’s Office

Ysleta Del Sur Pueblo

Federal Departments and Agencies

Federal Aviation Administration

Federal Bureau of Investigation

Federal Emergency Management Agency

Homeland Security Investigations

National Transportation Safety Board

North Texas Joint Terrorism Task Force

Transportation Security Administration

U.S. Air Force

U.S. Attorney’s Office – Eastern, Western, Southern and Northern Districts of Texas

U.S. Customs and Border Protection

U.S. Marshals Service

Non-Governmental Organizations

American Red Cross

Border Regional Advisory Council

El Paso Children’s Hospital

El Paso Specialty Hospital

Las Palmas Medical Center

The Hospitals of Providence: Sierra Campus, Memorial Campus, Transmountain Campus, East Campus and Del Sol

The Salvation Army