#Kiev Opera Ballet

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Yekaterina Kurchenko Екатерина Курченко

Yekaterina Kurchenko Екатерина Курченко as “Giselle”, “Giselle Жізель”, libretto by Théophile Gautier, Jules Henri Vernoy de Saint Georges, Jean Coralli, choreo by Charles Perrault, Jean Coralli, Marius Petipa, music by Adolphe Adam, National Opera and Ballet Theatre of Ukraine Національна Опера України, Kiev, Ukraine.

Note: Original quality of photographs might be affected by compression algorithm of the website where they are hosted.

Source and more info at: Yekaterina Kurchenko on Instagram

#Dans#Danse#Dance#Danza#Dancer#Dansen#Balet#Ballet#Балет#Ballett#Balletto#Balerino#Balerina#Ballerina#Ballerino#Bailarina#Балерина#Танец#Tänzer#Танцор#Adolphe Adam#Charles Perrault#Жізель#Giselle#Jean Coralli#Jules Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges#Marius Petipa#National Opera and Ballet Theatre of Ukraine Національна Опера України#Théophile Gautier#Yekaterina Kurchenko Екатерина Курченко

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

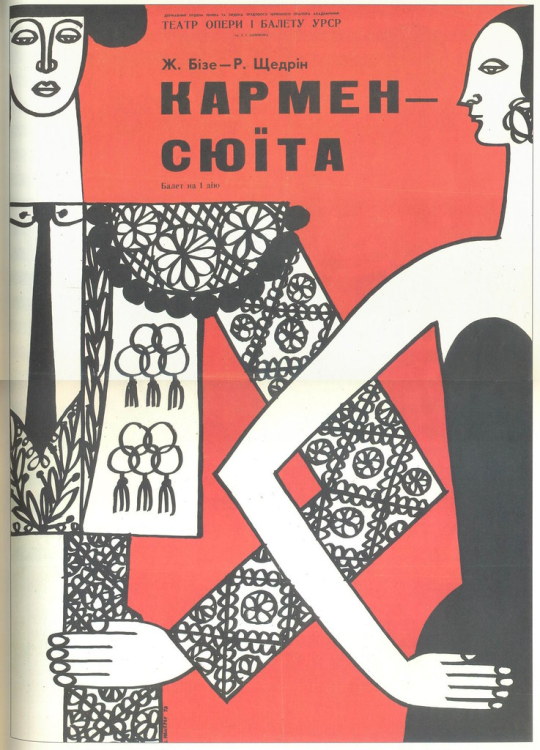

Boris Messerer, Carmen Suite, 1973

Scanned from the book "The Soviet Arts Poster, 1917-1987", Penguin Books.

Georges Bizet - Rodion Shchedrin. Carmen Suite: Ballet in one act, Shevchenko Opera and Ballet Theatre of the Ukraine (Kiev). Colour offet. 95 X 65.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Солист балета - родился в балетной семье, в соответствующую дату!

С Праздником!

#international dance day#международный день танца#міжнародний день танцю#dies internationalis saltationis#балет#Киев Опера Балет#Kiev Opera Ballet#классическаямузыка#киев

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Artists of the Kiev Opera and Ballet Theater. Photo by Robert Diament (1931).

500 notes

·

View notes

Note

russian opera recs???? please??????? I want to broaden my horizons

I am so excited that you're interested!!! You are in for such a treat.

I did a write-up of my favorite Russian operas yesterday evening, which is here. I gushed a whole bunch about my faves and recommended a handful of specific tracks on Spotify to get a feel for things. So definitely check that out.

Buuuuut since you've given me another opportunity here-- let's talk about the New Russian School. This is the music of Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky-- what they and their characters listened to.

The New Russian School was a 19th century movement among composers to create a distinctly Russian style of music. It was spearheaded by the Mighty Five, a group of five composers including my beloved Modest Mussorgsky (my top two on the opera post are his work). But they didn't just write operas! They also wrote parlor songs, symphonies, ballets, marches-- you name it. If you want to get a real feel for Russian music, this is where you start. Some highlights:

- All of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition is wonderful, but “The Great Gate of Kiev” is just grand and magnificent and magical in all the best ways. I swear, it makes me want to weep for joy.

- "The Field Marshall," part of Mussorgsky's Songs and Dances of Death, is sung from the perspective of Death riding through a battlefield after a battle. It's everything you want from that evocative premise.

- "Russia," Mily Balakirev is a symphonic piece that's meant to try and encapsulate the Russian identity. It's beautiful: moody in places, sprightly in others, dramatic, languid, mercurial. Surprisingly good study music, somehow?

- “Islamey” from Balakirev’s Oriental Fantasy is reasonably well known in the West, but it’s so much fun. That’s all I’ve got to say about it. It totally slaps.

- “The Lark” from A Farewell to Petersburg (also Balakirev) is just so sweet and sad and delicate. It settles my heart so wonderfully.

- Rimsky-Korsakov's Russian Easter Overture is just glorious. It's the sort of music that grows in beauty and hope from its first strains. It's sunrise on Easter and everyone waking up and getting dressed and going to church. It's mounting excitement of Easter morning and the joy of celebrating the Resurrection.

- Parlor music! You know how in Tolstoy novels a character (or several) will sing something at a private party or gathering? That’s this stuff. Alexander Dargomyzhsky’s is some of the best. I quite like “Enchant Me, Enchant” because I can so easily imagine Natasha singing it. “The Old Corporal” is quite good too. Full disclosure, I mostly listen to Dargomyzhsky while thinking about Tolstoy novels ;)

- A wonderful cello nocturn by Alexander Borodin. Mournful, but with moments of joy and lightness. Perfectly balanced. My mom really likes this one.

Oh goodness, Cesar Cui is the last member of the Mighty Five and I can’t think of anything of his that I really love off the top of my head. So sorry Cesar! I should listen to more of your stuff.

-Tchaikovsky came after the Mighty Five, but was definitely a product of the New Russian School and I need to talk about his Sixth Symphony. His Sixth Symphony (called Pathetique) is popular in the West, but not many know the story and significance behind it. Tchaikovsky was coming to the end of his life and old St. Petersburg was coming to the end of its. Pathetique quotes from the Russian Orthodox funeral service. Its last movement incorporates De Profundis, a prayer for the dead. The Symphony is beautiful and mournful and, when it premiered, the curtain fell not to applause but to weeping. The Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich ran up to Tchaikovsky crying "What have you done? It's a requiem, a requiem!" Ya know that scene in the movie Amadeus where Mozart writes his own death mass in bed and then dies? Yeah. Except in a way, this was a requiem for the Russia that died with the revolution as well. Tchaikovsky was a lot like Akhmatova in that he looked at Old Russia with nostalgia before it was even gone.

Bonus: I like bombast. Here's Glinka's Patriotic Song. Glinka predates all these other guys, but he's wonderful and really deserves to be better known in the West. In Russia, he's like their Mozart.

Between this and the opera post, I hope I haven’t overwhelmed anyone. During quarantine, I used to go for drives with my mom and sister basically every day. Occasionally, I played my Russians and my mom’s response was “this makes the pandemic feel a lot more epic, doesn’t it?”

#i could go on#just. Russia man#russia where are you flying to?#how can i keep from singing#ask me hard questions

103 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Daniil Silkin - ballet of the National Opera of Ukraine in Kiev

#daniil silkin#national opera of ukraine#nyc dance project#stuttgart ballet#dancer#danseur#ballerino#bailarín#tänzer#ukrainian ballet dancers#boys of ballet#ballet men

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Robert Diament “Composition of artists of the Taras Shevchenko Kiev Opera and ballet theater”. 1931 Роберт Диамент “Композиция артистов Киевского театра оперы и балета имени Тараса Шевченко”. 1931

#ussr#soviet#soviet union#Soviet life#daily life#ссср#русский tumblr#русский тамблер#русский блог#русский пост

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pas De Deux - A Moodboard (Three Part) One-Shot (Part Three)

@iamnottrisha - thanks for organizing!

@taamagams - thanks for creating this beautiful moodboard!

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

They split the bill for dinner, and then Claire let Jamie take her hand and lead her across the street. Lights in the fountain sparked reflections across all three buildings at Lincoln Center.

“I’ve never been here before,” she breathed.

Jamie pulled her tightly against his side, watching people bustle about the complex. “I’m glad to give this to you,” he whispered, kissing her temple.

Something surged within her – but Jamie was already tugging at her hand, striding toward the building at the back of the square.

“Sometimes I’m sorry that I didn’t see the original Metropolitan Opera House, before this complex was built by Robert Moses in the 60s.” Jamie’s voice was strong, quiet, as they approached the theater. “But I do have to say – there’s something very special about this place.”

Once inside, he went directly to the Will Call.

“Two for tonight’s performance, please. Last name is Fraser.”

And then she stared down at her ticket.

“Swan Lake,” she whispered.

“Of course. I told you it’s one of my favorites. But I didn’t tell you that my sister Jenny is dancing in it tonight.”

Stunned, Claire met his smiling eyes.

“How else do you think I could have afforded these tickets?”

--

Walking up the curving, red carpeted staircase to their seats was like something out of a dream.

“Some people say that orchestra seating is the best,” Jamie explained as they carefully walked down the sloping aisle to their seats at the front of the balcony. “But I like sitting up here – you can see the entire stage, plus the musicians.”

Heavy gold curtains draped across the stage. Claire watched individual musicians warm up in the pit, practicing their scales, laughing with each other.

“How long has your sister been with the ballet company?”

“About ten years now – she’s worked her way up to be what they call a principal dancer. And one of only a handful of dancers in the New York City ballet who are actually from New York City. The company truly seeks the best talent from all around the world.”

Claire thumbed through her Playbill – Jamie was right. Dancers hailed from Kiev, and Buenos Aires, and Paris, and Moscow, and Los Angeles.

“I don’t see a Fraser,” she frowned.

Jamie’s finger pointed out a smiling, dark-haired woman. “Janet Murray. She’s married to my best friend Ian – we all went to school together. She’s one of the only married dancers.”

“Is Ian a dancer as well?”

“God, no!” Jamie laughed. “He’s a police officer. Passed the sergeant’s exam earlier this year.”

Claire shook her head, then squinted at Jenny’s photograph. “I’d expected she’d be red-haired, like you.”

“She takes after Dad’s side of the family – they were all much darker in complexion. I take after Mom’s side.”

She turned the page. “Jenny is dancing Odette. Is that the main character?”

“Yes. She’s danced in this ballet many times, but only this season she’s started dancing Odette.”

Claire set down her Playbill, and took both of Jamie’s hands. “Thank you for taking me here. It’s – it’s all so much more than I ever could have expected.”

He raised one of her hands to his lips, and kissed it ever so gently. “Thank you for allowing me to take you here. It’s…I’ve never had anyone to share this with. Who would appreciate it.”

He flushed.

“Did you ever dance ballet, Jamie?”

“I tried – but I don’t have the coordination for it. I’d rather be drawing.”

“So – what do you draw?”

“Whatever I see around me. I like charcoal – it’s so simple, so freeing. Just a few strokes and life begins to take shape.”

She crossed one leg, rubbing her boot against his. “Anything in particular that you like to draw?”

“People. Faces. I drew a lot of dancers when Jenny and I were growing up – I had my Degas phase. It’s very hard to capture movement accurately.”

“Would you like to draw me?”

Quickly Jamie glanced at his watch, then fished around in his jacket pocket, producing a small rectangular metal case.

“That looks like what my uncle would put his cigarettes in.”

He lay the case on the armrest between them, and carefully flicked it open. “It used to be something like that.” He turned it around so that Claire could see inside – six neat rectangles of chalk, black and white and four shades of gray. “Now I never leave home without it.”

He flipped through his Playbill, removed the paper insert announcing the casting change for the night, and placed it, blank side up, on his knees. He turned in his seat, balancing carefully, facing her. Began to draw.

Suddenly self-conscious, Claire swallowed, feeling her cheeks flush.

“Hold still,” he whispered, eyes flicking between her face and the paper.

She did, mind racing, watching as he rotated the paper, smudged it a bit with the pads of his fingers, then smiled once it was all done.

“Here.” He held it out between them.

It was her, all right – rendered in the most delicate of lines. With just three sweeps of chalk he had captured her brow, cheeks, nose, chin – and smile.

Simple. Stunning.

She swallowed, fishing in her purse for a tissue. “Here – I didn’t see anything in that case to clean your hands with.”

Tentatively she took the drawing, studying it as he wiped his hands.

“It’s amazing how quickly you can do that.”

“It’s easy when I have a beautiful subject.”

She closed her eyes. Knowing he could see her hands shake.

“What are we doing, Jamie?”

“We’re going to watch the ballet. I’ll hold you close to me, and tell you the story, and hope against hope that you’ll continue to open your heart to me. And then when it’s done, I’ll introduce you to my sister. Maybe we’ll go for a drink. And I’ll see you back home to Adso.”

His warm, warm hand carefully rested on her knee. “I hope that one day, you’ll see this drawing and remember every moment – every second – of this night.”

She swallowed. “I can’t believe I found you.”

Her hand found his. Carefully he slipped the drawing into his Playbill, set it on the floor, and enveloped her hand in between both of his. “We found each other, Claire.”

Then a chime sounded, and the light fixtures began ascending up to the ceiling, and they settled into their seats – Jamie’s strong arm around her back, his hand safe between both of Claire’s.

He kept his promises that night.

Whispering the story unfolding on the stage:

That’s Prince Siegfried, and his overbearing mother who tells him he must choose a bride at the royal ball. He’s upset that he can’t marry for love. His buddies try to cheer him up, but it’s no use. As evening falls, Siegfried sees a flock of swans flying overhead, and suggests they go on a hunt to clear his mind.

Now here we pick up the story a bit later – and we see Siegfried lost at the lakeside. A flock of swans lands – and just as he aims his bow, one of them transforms into Odette. I can say Odette, and not Jenny, because to be honest I can’t recognize her with her hair and makeup and costume. You can see how terrified she is – but Siegfried explains that he won’t harm her. She tells him that she and the other swans are the victims of a curse from an evil sorcerer. By day they are swans, and by night, beside this enchanted lake, they regain their human form.

Odette tells him that the spell can only be broken if a man who has never loved before, swears to Odette that he will love her forever.

Then the sorcerer appears, and Siegfried wants to kill him – but Odette persuades him not to, for she fears that if the sorcerer dies, she will be cursed to live under the terrible spell forever.

Odette and Siegfried fall in love, that night by the lake – and as dawn breaks, she and her companions turn into swans again.

Now here we are the following evening at the costume ball – where Siegfried has been ordered to find a wife. Here are the girls his mother wants him to marry. And look – here is the sorcerer, in disguise, with his daughter who is disguised to resemble Odette. Siegfried gives her attention, thinking she is Odette.

And now we see Odette appear in her human form, trying desperately to warn Siegfried – but he doesn’t see her. And he proclaims to the court that he will marry the sorcerer’s daughter. But then the sorcerer shows Siegfried a magical vision of Odette – and he realizes she’s not there. He flees the castle, hurrying back to the lake to find her.

Odette is distraught. Siegfried appears and apologizes. Odette realizes she can never have the life with him that she wants, so she chooses to die. Siegfried chooses to die with her, and they leap into the lake. This breaks the sorcerer’s spell over the other swans. He dies. And in the last scene of the ballet, the swan maidens watch Siegfried and Odette ascend to heaven together.

The orchestra rose to a crashing crescendo, followed by a sliver of silence. The crowd rose to its feet with thundering applause.

Claire turned to Jamie, tears streaking down her face. She caressed his cheek and pulled him close for a long, long, sweet kiss.

“I’ve never loved before, Claire,” he rasped against her lips. “But I hope – ”

“I only want to be under your spell, Jamie,” she whispered, pulling him back for more.

267 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yekaterina Kurchenko Екатерина Курченко

Yekaterina Kurchenko Екатерина Курченко as “Giselle”, “Giselle Жізель”, libretto by Théophile Gautier, Jules Henri Vernoy de Saint Georges, Jean Coralli, choreo by Charles Perrault, Jean Coralli, Marius Petipa, music by Adolphe Adam, National Opera and Ballet Theatre of Ukraine Національна Опера України, Kiev, Ukraine.

Note: Original quality of photographs might be affected by compression algorithm of the website where they are hosted.

Source and more info at: Yekaterina Kurchenko on Instagram

#Dans#Danse#Dance#Danza#Dancer#Dansen#Balet#Ballet#Балет#Ballett#Balletto#Balerino#Balerina#Ballerina#Ballerino#Bailarina#Балерина#Танец#Tänzer#Танцор#Adolphe Adam#Charles Perrault#Жізель#Giselle#Jean Coralli#Jules Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges#Marius Petipa#National Opera and Ballet Theatre of Ukraine Національна Опера України#Théophile Gautier#Yekaterina Kurchenko Екатерина Курченко

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anna Muromtseva (first soloist in Kiev National Opera and Ballet Theatre of Ukraine

Photographer Ksenia Orlova

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

XE3F8753 – Mijaíl Glinka (Михаил Иванович Глинка), Tikhvin Cemetery (Saint Petersburg)

Mijaíl Ivánovich Glinka (en ruso: Михаил Иванович Глинка; Novospásskoie, provincia de Smolensk, 1 de junio de 1804-Berlín, 15 de febrero de 1857) fue un compositor ruso, considerado el padre del nacionalismo musical ruso. Durante sus viajes visitó España, donde conoció y admiró la música popular española, de la cual utilizó el estilo de la jota en su obra La jota aragonesa. Recuerdos de Castilla, basado en su prolífica estancia en Fresdelval, «Recuerdo de una noche de verano en Madrid», sobre la base de la obertura La noche en Madrid, son parte de su música orquestal. El método utilizado por Glinka para arreglar la forma y orquestación son influencia del folclore español. Las nuevas ideas de Glinka fueron plasmadas en “Las oberturas españolas”. Glinka fue el primer compositor ruso en ser reconocido fuera de su país y, generalmente, se lo considera el ‘padre’ de la música rusa. Su trabajo ejerció una gran influencia en las generaciones siguientes de compositores de su país. Sus obras más conocidas son las óperas Una vida por el Zar (1836), la primera ópera nacionalista rusa, y Ruslán y Liudmila (1842), cuyo libreto fue escrito por Aleksandr Pushkin y su obertura se suele interpretar en las salas de concierto. En Una vida por el Zar alternan arias de tipo italiano con melodías populares rusas. No obstante, la alta sociedad occidentalizada no admitió fácilmente esa intrusión de "lo vulgar" en un género tradicional como la ópera. Sus obras orquestales son menos conocidas. Inspiró a un grupo de compositores a reunirse (más tarde, serían conocidos como "los cinco": Modest Músorgski, Nikolái Rimski-Kórsakov, Aleksandr Borodín, Cesar Cui, Mili Balákirev) para crear música basada en la cultura rusa. Este grupo, más tarde, fundaría la Escuela Nacionalista Rusa. Es innegable la influencia de Glinka en otros compositores como Vasili Kalínnikov, Mijaíl Ippolítov-Ivánov, y aún en Piotr Chaikovski. es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mijaíl_Glinka es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Los_Cinco_(compositores)

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka (Russian: Михаил Иванович Глинка; 1 June [O.S. 20 May] 1804 – 15 February [O.S. 3 February] 1857) was the first Russian composer to gain wide recognition within his own country, and is often regarded as the fountainhead of Russian classical music. Glinka’s compositions were an important influence on future Russian composers, notably the members of The Five, who took Glinka’s lead and produced a distinctive Russian style of music. Glinka was born in the village of Novospasskoye, not far from the Desna River in the Smolensk Governorate of the Russian Empire (now in the Yelninsky District of the Smolensk Oblast). His wealthy father had retired as an army captain, and the family had a strong tradition of loyalty and service to the tsars, while several members of his extended family had also developed a lively interest in culture. His great-great-grandfather was a Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth nobleman, Wiktoryn Władysław Glinka of the Trzaska coat of arms. As a small child, Mikhail was raised by his over-protective and pampering paternal grandmother, who fed him sweets, wrapped him in furs, and confined him to her room, which was always to be kept at 25 °C (77 °F); accordingly, he developed a sickly disposition, later in his life retaining the services of numerous physicians, and often falling victim to a number of quacks. The only music he heard in his youthful confinement was the sounds of the village church bells and the folk songs of passing peasant choirs. The church bells were tuned to a dissonant chord and so his ears became used to strident harmony. While his nurse would sometimes sing folksongs, the peasant choirs who sang using the podgolosochnaya technique (an improvised style – literally under the voice – which uses improvised dissonant harmonies below the melody) influenced the way he later felt free to emancipate himself from the smooth progressions of Western harmony. After his grandmother’s death, Glinka moved to his maternal uncle’s estate some 10 kilometres (6 mi) away, and was able to hear his uncle’s orchestra, whose repertoire included pieces by Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. At the age of about ten he heard them play a clarinet quartet by the Finnish composer Bernhard Henrik Crusell. It had a profound effect upon him. "Music is my soul", he wrote many years later, recalling this experience. While his governess taught him Russian, German, French, and geography, he also received instruction on the piano and the violin. At the age of 13, Glinka went to the capital, Saint Petersburg, to study at a school for children of the nobility. Here he learned Latin, English, and Persian, studied mathematics and zoology, and considerably widened his musical experience. He had three piano lessons from John Field, the Irish composer of nocturnes, who spent some time in Saint Petersburg. He then continued his piano lessons with Charles Mayer and began composing. When he left school his father wanted him to join the Foreign Office, and he was appointed assistant secretary of the Department of Public Highways. The work was light, which allowed Glinka to settle into the life of a musical dilettante, frequenting the drawing rooms and social gatherings of the city. He was already composing a large amount of music, such as melancholy romances which amused the rich amateurs. His songs are among the most interesting part of his output from this period. In 1830, at the recommendation of a physician, Glinka decided to travel to Italy with the tenor Nikolai Kuzmich Ivanov. The journey took a leisurely pace, ambling uneventfully through Germany and Switzerland, before they settled in Milan. There, Glinka took lessons at the conservatory with Francesco Basili, although he struggled with counterpoint, which he found irksome. Although he spent his three years in Italy listening to singers of the day, romancing women with his music, and meeting many famous people including Mendelssohn and Berlioz, he became disenchanted with Italy. He realized that his mission in life was to return to Russia, write in a Russian manner, and do for Russian music what Donizetti and Bellini had done for Italian music. His return route took him through the Alps, and he stopped for a while in Vienna, where he heard the music of Franz Liszt. He stayed for another five months in Berlin, during which time he studied composition under the distinguished teacher Siegfried Dehn. A Capriccio on Russian themes for piano duet and an unfinished Symphony on two Russian themes were important products of this period. When word reached Glinka of his father’s death in 1834, he left Berlin and returned to Novospasskoye. While in Berlin, Glinka had become enamored with a beautiful and talented singer, for whom he composed Six Studies for Contralto. He contrived a plan to return to her, but when his sister’s German maid turned up without the necessary paperwork to cross to the border with him, he abandoned his plan as well as his love and turned north for Saint Petersburg. There he reunited with his mother, and made the acquaintance of Maria Petrovna Ivanova. After he courted her for a brief period, the two married. The marriage was short-lived, as Maria was tactless and uninterested in his music. Although his initial fondness for her was said to have inspired the trio in the first act of opera A Life for the Tsar (1836), his naturally sweet disposition coarsened under the constant nagging of his wife and her mother. After separating, she remarried. Glinka moved in with his mother, and later with his sister, Lyudmila Shestakova. A Life for the Tsar was the first of Glinka’s two great operas. It was originally entitled Ivan Susanin. Set in 1612, it tells the story of the Russian peasant and patriotic hero Ivan Susanin who sacrifices his life for the Tsar by leading astray a group of marauding Poles who were hunting him. The Tsar himself followed the work’s progress with interest and suggested the change in the title. It was a great success at its premiere on 9 December 1836, under the direction of Catterino Cavos, who had written an opera on the same subject in Italy. Although the music is still more Italianate than Russian, Glinka shows superb handling of the recitative which binds the whole work, and the orchestration is masterly, foreshadowing the orchestral writing of later Russian composers. The Tsar rewarded Glinka for his work with a ring valued at 4,000 rubles. (During the Soviet era, the opera was staged under its original title Ivan Susanin). In 1837, Glinka was installed as the instructor of the Imperial Chapel Choir, with a yearly salary of 25,000 rubles, and lodging at the court. In 1838, at the suggestion of the Tsar, he went off to Ukraine to gather new voices for the choir; the 19 new boys he found earned him another 1,500 rubles from the Tsar. He soon embarked on his second opera: Ruslan and Lyudmila. The plot, based on the tale by Alexander Pushkin, was concocted in 15 minutes by Konstantin Bakhturin, a poet who was drunk at the time. Consequently, the opera is a dramatic muddle, yet the quality of Glinka’s music is higher than in A Life for the Tsar. He uses a descending whole tone scale in the famous overture. This is associated with the villainous dwarf Chernomor who has abducted Lyudmila, daughter of the Prince of Kiev. There is much Italianate coloratura, and Act 3 contains several routine ballet numbers, but his great achievement in this opera lies in his use of folk melody which becomes thoroughly infused into the musical argument. Much of the borrowed folk material is oriental in origin. When it was first performed on 9 December 1842, it met with a cool reception, although it subsequently gained popularity. Glinka went through a dejected year after the poor reception of Ruslan and Lyudmila. His spirits rose when he travelled to Paris and Spain. In Spain, Glinka met Don Pedro Fernández, who remained his secretary and companion for the last nine years of his life. In Paris, Hector Berlioz conducted some excerpts from Glinka’s operas and wrote an appreciative article about him. Glinka in turn admired Berlioz’s music and resolved to compose some fantasies pittoresques for orchestra. Another visit to Paris followed in 1852 where he spent two years, living quietly and making frequent visits to the botanical and zoological gardens. From there he moved to Berlin where, after five months, he died suddenly on 15 February 1857, following a cold. He was buried in Berlin but a few months later his body was taken to Saint Petersburg and re-interred in the cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Monastery. Glinka was the beginning of a new direction in the development of music in Russia Musical culture arrived in Russia from Europe, and for the first time specifically Russian music began to appear, based on the European music culture, in the operas of the composer Mikhail Glinka. Different historical events were often used in the music, but for the first time they were presented in a realistic manner. The first to note this new musical direction was Alexander Serov. He was then supported by his friend Vladimir Stasov, who became the theorist of this musical direction. This direction was developed later by composers of "The Five". The modern Russian music critic Viktor Korshikov thus summed up: "There is not the development of Russian musical culture without…three operas – Ivan Soussanine, Ruslan and Ludmila and the Stone Guest have created Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov and Borodin. Soussanine is an opera where the main character is the people, Ruslan is the mythical, deeply Russian intrigue, and in Guest, the drama dominates over the softness of the beauty of sound." Two of these operas – Ivan Soussanine and Ruslan and Ludmila – were composed by Glinka. Since this time, the Russian culture began to occupy an increasingly prominent place in world culture. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mikhail_Glinka en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Five_(composers)

Posted by Enrique R G on 2019-09-12 09:20:20

Tagged: , Mijaíl Ivanovich Glinka , Михаил Иванович Глинка , Mijaíl Glinka , Михаил Глинка , Glinka , Глинка , Tikhvin Cemetery , Cementerio Tijvin , Тихвинское кладбище , New Lazarevsky , Ново-Лазаревским , Tijvin , Tikhvin , Тихвинское , San Petersburgo , Saint Petersburg , Санкт-П��тербург , Peterburg , Piter , Питер , Петрогра́д , Petrogrado , Петроград , Leningrado , Ленинград , Rusia , Russia , Россия , Venecia del Norte , Window to the West , Window to Europe , Venice of the North , Russian Venice , Fujifilm XE3 , Fuji XE3 , Fujinon 18-135

The post XE3F8753 – Mijaíl Glinka (Михаил Иванович Глинка), Tikhvin Cemetery (Saint Petersburg) appeared first on Good Info.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dreaming of winter holidays in Paris.

Left to right, top to bottom: Café Pouchkine’s snow-draped sign, Instagram; nativity scene in the Church of La Madeleine; map of Christmas markets; Notre-Dame Cathedral by Peter Rowley, Flickr; Galette des Rois (a cake served on and around Epiphany) by Steph Grey, Flickr; the Kiev Opera Ballet's guest performance of the Nutcracker at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées; the Eiffel Tower by Fabien Barrau via Tour Eiffel Officielle, Instagram; À la Mère de Famille, Instagram; cone of roasted chestnuts, source unidentified.

102 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kiev National Ballet | National Opera of Ukraine

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

We took the train to Kyiv (apparently Kyiv is the transliteration of Ukrainian "Киïв" and Kiev of Russian "Киев", so the spelling becomes a somewhat political matter, but also one of search engine optimization, which I don't particularly care about so I might as well use Kyiv). None of the night trains arrived at a decent time, so we took a day train and spent 6 of 7 hours trapped in the seats immediately next to a family with a very vocal baby and toddler. Thankfully they frequently took them out to wail in the corridor between carriages.

I still get extremely anxious when it comes time to take any kind of transport to another city, which doubles when another person is involved, and triples if we arrive at night and need to get to some distant and confusingly located accommodation. I've also finally realized that the best way to win a battle with my anxiety is to not fight it in the first place. My partner's mum (so worried about us setting foot in the Evil Lands of the East that she made him promise we wouldn't couchsurf on this trip) sponsored us a night at the hotel immediately next to the train station. It was delightful. The breakfast buffet was fantastic. There were foreign language channels on the TV. We checked out at 12 and tried to walk around before heading to the Airbnb but only made it as far as the yellow church pictured above because it was oppressively hot and such a mission was only doomed to end in a lot of sweat.

I'm going to try to blank the central Kyiv metro noon rush-hour ordeal out of my memory.

After calming down at the Airbnb we went back to the center to see Swan Lake at the National Opera of Ukraine. I had read the plot synopsis and was ready for the main characters to die at the end but instead there was a battle with Siegfried defeating von Rothbart, and Odette becoming human. Apparently this version originates from the Soviet demand for a happy ending and is often performed in Russia and China. I've now seen more ballet in the past month than all of my previous life combined (which was none). It's actually quite enjoyable if one enjoys sparkly outfits, leaping about (well, watching other people leap about, at least), and well-defined ass in tights. I know what I shall be doing if I ever make it to Minsk or Moscow!

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Daniil Silkin - ballet of the National Opera of Ukraine in Kiev

#daniil silkin#national ballet of ukraine#ukrainian ballet dancers#dance#balle#dancer#danseur#ballerino#bailarín#tänzer#boys of ballet#ballet men

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charity project OFF-Stage

Photographer: Vera Blansh

Creative director: Eugen Khandusenko

Fashion stylist: Nastya Velegura

Fashion Stylist Assistant: Ira Kravchenko

Make-ap artist: Anna Skuridina

Hair stylist: Oksana Cherepania

Model: Ann Simon (KModels Modeling Agency)

Ballet Dencer: Artem Shoshin

Location: Kiev Municipal Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre for Children and Youth

Artists of House of veterans of the scene named after Natalia Uzhviy

0 notes