#MSX Magazine

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Cover Illustrations for MSX Magazine by Naoyuki Katō / 加藤 直之

(September 1990 - October 1991)

#msx magazine#naoyuki kato#art#illustration#traditional painting#oilpainting#cover art#old school art#japan art#90s#retro scifi#space ship

286 notes

·

View notes

Text

MSX Magazine, 1992-07

192 notes

·

View notes

Text

MSX Magazine / The Flying Luna Clipper (1987) ᯓ★

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snatcher - MSX Magazine, 1988 issue 11

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

MSX Magazine - 1991/05

#computer magazine#vintage magazine#magazine#msx magazine#computer#art#text#video games#metal gear solid#mgs#japanese#japanese magazine

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

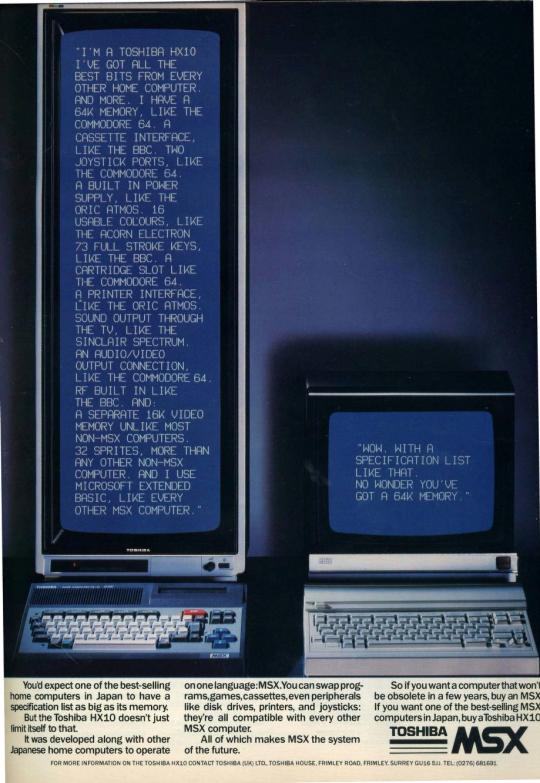

#msx#old tech#1980s#blue aesthetic#eyeroll#blue#vaporwave#webcore#magazine#.#computers#toshiba#toshiba HX10#retro tech

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eight Bit Magazine Issue 12

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

" You can learn various programs while having fun! You too, PC users! "

MSXFAN n06 - June, 1988

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

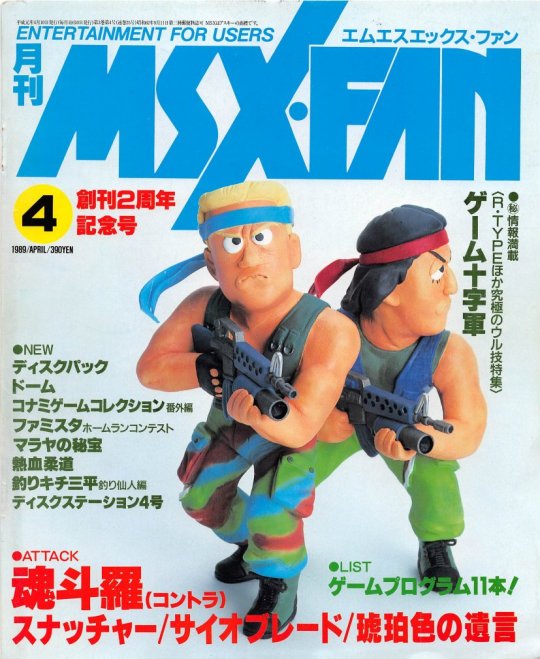

月刊MSX・FAN 1989年4月号

MSX Fan Magazine #4 - Contra

271 notes

·

View notes

Text

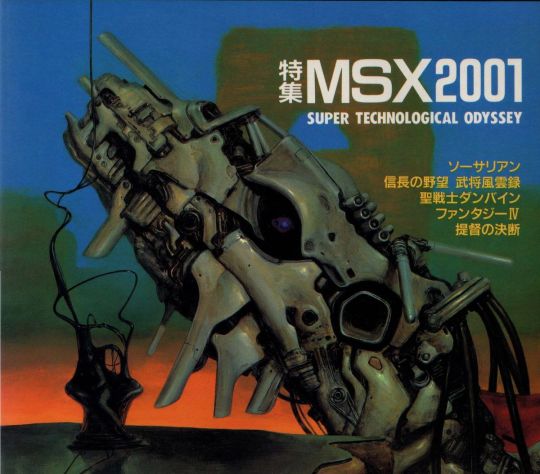

Cover art by Naoyuki Kato for MSX Magazine (Jul 1991)

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Compile Hagiography Through Reading the Hyperdimension Neptunia Wiki

12 Days of Aniblogging 2023, Day 4

When I’m really bored on the computer, one of the things I'll occasionally do is explore the Hyperdimension Neptunia wiki. Neptunia is a role-playing series whose main distinction is being centered around moe anthropomorphizations of video game companies and consoles, which fascinates me. These are textbook trashy 6/10 anime RPGs, and release at a pace that suggests both a low budget and a pretty dedicated fanbase. I don’t mean to patronize, though. I’m not above this kind of stuff, I just can’t let a bunch of mid 30-hour JRPGs into my life at this moment in time. Rather, my angle of interest here is the origins of the Neptunia developer, Compile Heart.

listening and learning

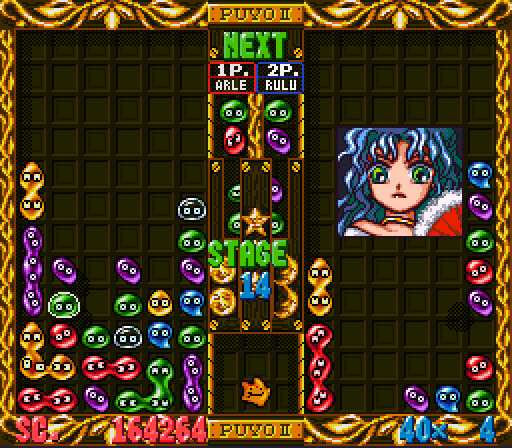

You see, back in the late 80s and early 90s, a company called Compile was one of the greats in Japanese home PC gaming. Most of their early output was shmups for the MSX, although they dabbled in a bit of everything, including running a disc magazine to distribute games. Compile’s first hit was Madou Monogatari in 1990, a numberless first-person dungeon crawler with a focus on voice samples. It features a lovable cast, starring young magician Arle Nadja as she attempts to graduate kindergarten, viscerally decapitate an evil sorcerer, and fend off Satan and the girl who’s down bad for Satan. Plenty of remakes and sequels followed, and eventually Compile struck gold with Puyo Puyo, the platonic ideal of competitive falling-block games. To set it apart from the more faceless puzzle games of the era, they reused the Madou Monogatari cast, resulting in a cutesy aesthetic with occasional lingering bits of fucked-up lore.

After porting Puyo Puyo and its sequel to everything imaginable, Compile spent their mid-90s rapidly scaling the company, ultimately biting off more than they could chew. This was an era of serious change as developers moved towards 3D, and consumer preferences moved too fast for Compile to adapt. Some high-profile failures like Madou Monogatari Saturn and Puyo Puyo Dungeon sent the company into a fiscal downward spiral, leading frequent business partner Sega to bail them out by buying the rights to Puyo Puyo. Compile got to finish their in-progress work, including the gorgeous yet frustrating Puyo Puyo 4, but the writing was on the wall. Compile declared bankruptcy in 2003 after throwing all of their hopes and dreams into one last little game, Pochi and Nyaa. It’s a puzzle game with simple yet strategic mechanics that feels like something of a return to infancy for the developers. Also, it was released on the Neo-Geo in 2003! If you know anything about arcade hardware, that’s nuts.

The late 90's pre-rendered backgrounds combined with Sunaho Tobe's character artwork give Puyo Puyo 4 such a special look. Shame it's unplayable unless you're very good at chaining.

So Compile scatters to the winds and a lot of the non-shmup devs regroup at the newly formed Compile Heart, where they eventually hit the jackpot with Hyperdimension Neptunia and crank one of those out per year ad infinitum.

That was a pretty tumultuous history! And Neptunia seems like a way to process this? After all, the protagonist is named after and personifies the Sega Neptune, a cancelled 90’s console. Compile and Sega have intertwined histories and faced a similar trajectory. Rapid success in the early 90s was followed up by bad business decisions later in the decade, leading to a tragic exit from the industry that nobody wanted to see. Hyperdimension Neptunia wants to convey these scars to an audience who weren't necessarily around for it.

The first Neptunia game opens with the anime girl manifestations of Nintendo, Sony, and Xbox deciding that in order to break the sixth-generation console war stalemate, they need to team up against the one who poses the biggest threat. So, they get together and betray Neptunia, casting her out of the heavens. Obviously, this isn’t how it happened in the real world. The Dreamcast may have been awesome, but Sega was operating at a loss trying to support it, and the release of the all-consuming PS2 spelled doom. But this intro is closer to how it felt to Sega fans. It’s a mythical retelling of the fall, one that slots right in with the endless glowing retrospectives of Sega’s glorious but doomed last breath (My favorite is calling the console a “small, square, white plastic JFK”).

I’m no industry expert or historian, but I was around to see the Japanese game industry flounder during the PS3 era, when high definition brought with it new expectations and inflated development cycles. Obviously juggernauts like Capcom and Square Enix got out fine, but a lot of smaller studios went under at some point in the past 15 years. Hudson, T&E Soft, ASCII, Clover Studio, Imageepoch. In another world, beloved FromSoft could have fallen to the wayside just as easily.

That’s why Neptunia is really important, I think. It serves as a way to self-mythologize, to keep fragments of these studios alive no matter what happens to them later. It’s a snapshot of all the B-tier Japanese game companies at any given point, written by one such company. When some of them inevitably fold, the Neptunia series will act as one more eulogy. As a huge fan of Compile-era Puyo Puyo, it’s a strange but relieving afterlife to witness. I may never play these games, but I’m grateful for what they do, and it’s a very entertaining series to rummage through the wiki of, especially as someone with a known appreciation of OS-tans.

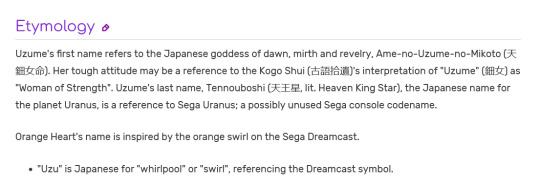

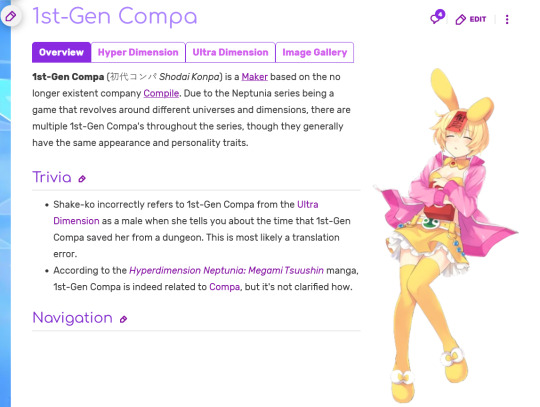

The second Hyperdimension Neptunia game appears to introduce the Gamindustri Graveyard, a burial ground for defunct game companies. Resting there alongside all the other fallen studios is 1st-Gen Compa, the spirit of Compile. She’s wearing an outfit adorned with Puyos, with ears resembling those of beloved mascot Carbuncle. What is just a random horny anime girl for one person is a loving tribute for another. It’s a meaningful way to send off the old.

…and so is raising the dead! In October, Compile Heart announced a new Madou Monogatari game, with Sega giving them the rights to use classic Puyo Puyo characters on the project. According to the press release, the development team includes many staff members who were part of the original incarnation of Compile. Hope springs eternal, somehow.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gradius (TG-16 Mini)

Perhaps amusingly given that it ended up owning the whole shebang, Konami's entrance to the PC Engine market came four years into the console's life. I'd imagine that had as much to do with navigating the relationship with Nintendo as anything else, but it's still interesting. Konami would go on to make a number of great games for the console, some iconic of the platform. But it started here in 1991 with a Japan-exclusive port of Konami's 1985 arcade hit, Gradius. By this point, the Super Famicom already had a port of Gradius III in its library, which you would think would make this look like meager scraps being tossed NEC's way.

Unfortunately, this is one case where I can't speak fully to the original context. The game was only released in Japan, and as such the only things I heard about it back in the day were through small snippets in magazines that covered imports. From what I can gather by searching around on the Japanese side of the Internet, PC Engine owners were surprised and excited when the game was announced. That's perhaps as much owing to the news that Konami would be making PC Engine games as it was to the port itself, but there was definitely a crowd that was looking forward to a more accurate version of the game than the beloved yet compromised Famicom Gradius.

The game certainly reviewed well enough, but I've found a lot of anecdotes that circle around the same sense of disappointment that the game wasn't as arcade-accurate as PC Engine fans felt it could have been. The color palette is more muted than the arcade game. Due to the differing resolution of the hardware, it was necessary to have the screen scroll vertically a bit even in stages where that didn't occur in the arcade. Some of the mechanics also differed slightly. It wasn't that the PC Engine Gradius was disliked per se, but some fans were disillusioned by it not being exactly what they had hoped for.

One of the popular theories now is that the differences stem from this being something of a remake of the MSX version of Gradius, with things like the extra bone-themed stage and the presence of some two-level power-ups being considered as evidence. Whatever the case, Konami has dutifully reissued this port on just about every occasion where it made sense to do so. I'm not surprised to see it here in the TG-16 Mini. And I think people have softened on this version of the game over the years, perhaps due to those very same deviations from the arcade original that is now far more readily available at home.

For my part, I enjoy this version of Gradius. It's a little easier than some other versions, and the slowdown is just about predictable enough that you can use it as a tool in your arsenal. The extra level isn't amazing, but it's nice to have it. And hey, the Konami Code works here too. It's never a bad thing to be able to instantly power up, even if it only works once per session. The game plays well and while its presentation might not be true to the arcade, it still looks and sounds good. I have this one on my Japanese Nintendo 3DS (there was a short-lived PC Engine Virtual Console here) and play it often.

With that said, if you want something closer to the arcade, M2 has once again provided in the TurboGrafx-16 Mini. Simply hold the Select button while choosing this game from the carousel and you'll boot into the new "Near Arcade" version. You'll know you did it right because the game will start with the iconic Konami Morning Music countdown from its Bubble System hardware. And yes, Gradius Near Arcade is just what it says on the tin. While the vertical scroll is still there, this otherwise looks, sounds, and plays far more like the arcade game than the original PC Engine Gradius. It almost feels like we've gotten a whole other game here. I think we all knew the console had it in it.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

SD Snatcher - MSX Magazine, 1990 issue 1

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Luis Royo's beautiful cover art for Game Over, developed by Dinamic Software and released in 1987 for the Amstrad CPC, Commodore 64, MSX, Thompson TO7, and ZX Spectrum.

I am a big fan of Royo's work. No, no, not just for all the nipples! Well... OK. If I"m being honest, nipples could very well be a factor. But not JUST because of the nipples, I can tell you that. The man makes some of the most gorgeous fantasy art I've seen.

The artwork was also used 3 years earlier for the February 1985 cover of French science fiction magazine Ere Comprimée.

#luis royo#game over#dinamic software#Dinamic Software art#Amstrad CPC art#Commodore 64 art#MSX art#Thompson TO7 art#ZX Spectrum art#PC art

22 notes

·

View notes