#Naskh

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Caligrafía Islámica: Un Viaje por la Escritura Sagrada y su Significado Estético

#arquitectura islámica#arte islámico#belleza estética#caligrafía árabe#caligrafía islámica#Corán#escritura sagrada#estilos caligráficos#Kufic#Naskh#Thuluth#tradición islámica

0 notes

Text

The Timeless Elegance of Arabic Calligraphy.

What skill would you like to learn? Arabic calligraphy is a fascinating and intricate art form that combines both visual aesthetics and the rich tradition of the Arabic language. This ancient practice involves writing Arabic script in a highly stylized and artistic manner. It holds immense cultural and historical significance in the Islamic world and beyond. Arabic calligraphy has evolved into…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Fritware tile with peony motif and Naskh inscription, Iran, probably Kashan, 1300-1325

V&A

116 notes

·

View notes

Note

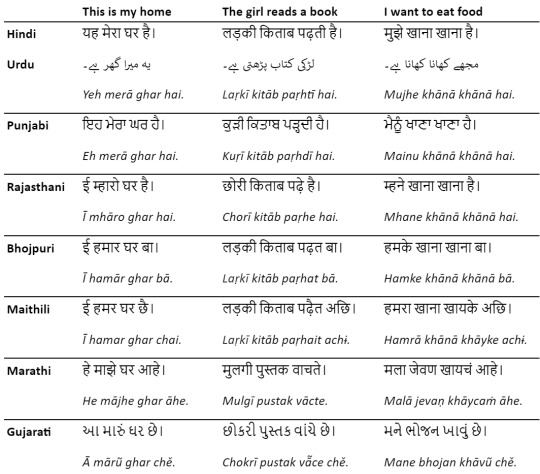

Are any of the other North Indian languages mutually intelligible with Hindi?

(other than Urdu)

Boy, did this ask take me down a rabbit hole. I have only studied Hindi and some Urdu, and my exposure to other Indian languages is mostly through fusion film songs that mix various languages. So if I make a mistake here, please feel free to expand and correct me!

India is home to a diverse range of languages, many of which share roots with Hindi in the Indo-Aryan language family. While some are highly mutually intelligible, others are more distinct but still share structural and lexical similarities.

When comparing languages with common roots, it's often helpful to look at the words that are probably the oldest, such as those for home, food, or basic verbs. Here's a comparison of Hindi and Urdu to six other Indian languages with three example sentences.

What we can see here:

Shared vocabulary: Words like घर, किताब and खाना are mostly consistent across the board and would likely be understood by many speakers of these languages. Words like पुस्तक, छोरी and भोजन are also familiar to Hindi speakers, though they might be considered more formal, regional or specific.

Grammar: all these languages follow the Subject-Object-Verb (SOV) sentence structure. Even if you encounter an unfamiliar word, this consistent syntax helps understanding and contextually deducing its meaning. Knowing where nouns, verbs and adverbs are likely placed in a sentence can be a huge advantage when learning or comparing these languages.

Script: Hindi uses Devanagari, Urdu uses Nastaliq or Naskh, Punjabi uses Gurmukhi in India and Shahmukhi (Perso-Arabian script similar to Urdu) in Pakistan. Gujarati has its own script, and others, like Maithili and Bhojpuri, also use Devanagari with minor regional tweaks.

So the answer to your question is: well yes, but actually no.

You can test how much you understand by listening to these songs! Some of them have a bit of Hindi influence or shared vocabulary mixed into them:

Punjabi

youtube

youtube

Rajasthani

youtube

youtube

Bhojpuri

youtube

Maithili

youtube

Marathi

youtube

youtube

Gujarati

youtube

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

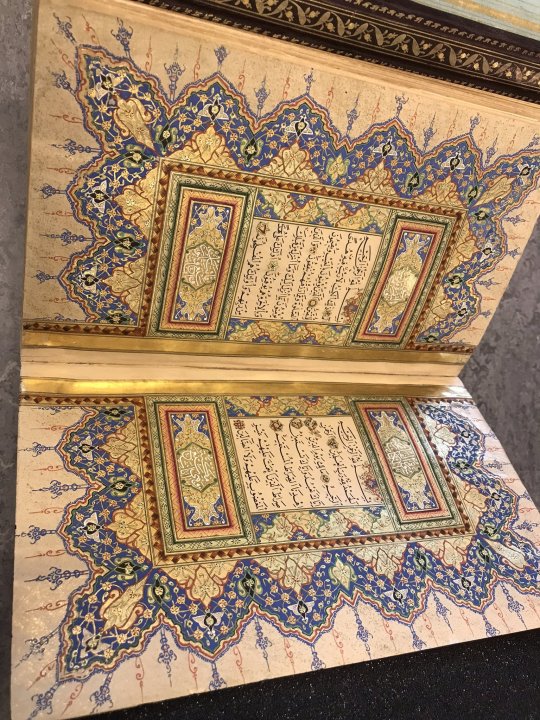

QUR’AN (17th Century)

A large size (51x37cm) illuminated copy of the QUR’AN made in Turkey. Ink and pigments on laid, non-European with flyleaves of Italian, pink tinted paper covered with leather. ‘This polychrome manuscript is penned in a number of scripts, including Muhaqqaq, Thuluth, Naskh, and Ttawqi’.

Previously owned by Sultan Ahmad (reigned 1703-1730). Held by the Walters Art Museum.

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#vintage books#illustrated book#book design#holy quran#turkey#17th century

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

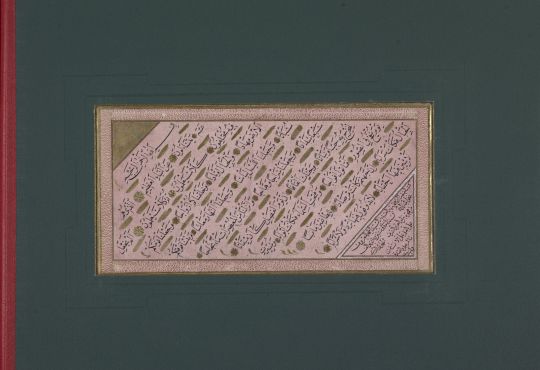

An outstanding icazetname in Isl. Ms. 438

First part of a calligraphy license or diploma (icazetname) in naskh (nesih) script, mounted in fol.17b in Isl. Ms. 438, Islamic Manuscripts Collection

Second part of a calligraphy license or diploma (icazetname) in naskh (nesih) script, mounted as a separate piece in fol.21a in Isl. Ms. 438, Islamic Manuscripts Collection

Enjoy this post by Sumeyra Dursun, 2023 Heid Fellow, from her research in the Islamic Manuscripts Collection. Sumeyra is a doctoral candidate in the history of Islamic arts at Yildiz Technical University in Istanbul.

Read more!

#libraries#archives#special collections#special collections libraries#libraries and archives#archival collections#archival research#rare books#rare books and special collections#archives and special collections#research fellowships#heid fellows#fellowships#islamic manuscripts#hat sanatı#hattat#hattatlar#el yazma#yazmalar#yazma eserler#ottoman culture#ottoman history#turkish arts#turkish history#ottoman art#calligraphy#calligraphers#calligraphic#calligraphy practice#calligraphy art

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Art of Illumination and Naskh Scrip by Hafez Osman Nuri (II Abdülhamid Collection, nr 173)

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

SPIRITUALITY IN ISLAM: PART 2: THE ORIGIN

As the history of Islamic religious sciences tells us, religious commandments were not written down during the early days of Islam; rather, the practice and oral circulation of commandments related to belief, worship, and daily life allowed the people to memorize them.

Thus it was easy to compile them in books later on, for what had been memorized and practiced was simply written down. In addition, since religious commandments were the vital issues in a Muslim’s individual and collective life, scholars gave priority to them and compiled books on them. Legal scholars collected and codified books on Islamic law and its rules and principles pertaining to all fields of life. Traditionists established the Prophetic traditions (hadiths) and way of life (Sunna), and preserved them in books. Theologians dealt with issues concerning Muslim belief. Interpreters of the Qur'an dedicated themselves to studying its meaning, including issues that would later be called “Qur'anic sciences,” such as naskh (abrogation of a law), inzal (God’s sending down the entire Qur'an at one time), tanzil (God’s sending down the Qur'an in parts on different occasions), qira'at (Qur'anic recitation), ta'wil (exegesis), and others.

Thanks to these efforts that remain universally appreciated in the Muslim world, the truths and principles of Islam were established in such a way that their authenticity cannot be doubted.

While some scholars were engaged in these “outer” activities, Sufi masters were mostly concentrating on the Muhammadan Truth’s pure spiritual dimension. They sought to reveal the essence of humanity’s being, the real nature of existence, and the inner dynamics of humanity and the cosmos by calling attention to the reality of that which lies beneath and beyond their outer dimension. Adding to Qur'anic commentaries, narrations of Traditionists, and deductions of legal scholars, Sufi masters developed their ways through asceticism, spirituality, and self-purification in short, their practice and experience of religion.

Thus the Islamic spiritual life based on asceticism, regular worship, abstention from all major and minor sins, sincerity and purity of intention, love and yearning, and the individual’s admission of his or her essential impotence and destitution became the subject matter of Sufism, a new science possessing its own method, principles, rules, and terms. Even if various differences gradually emerged among the orders that were established later, it can be said that the basic core of this science has always been the essence of the Muhammadan Truth.

The two aspects of the same truth the commandments of the Shari'a and Sufism have sometimes been presented as mutually exclusive. This is quite unfortunate, as Sufism is nothing more than the spirit of the Shari'a, which is made up of austerity, self-control and criticism, and the continuous struggle to resist the temptations of Satan and the carnal, evil-commanding self in order to fulfill religious obligations. While adhering to the former has been regarded as exotericism (self-restriction to Islam’s outer dimension), following the latter has been seen as pure esotericism. Although this discrimination arises partly from assertions that the commandments of the Shari'a are represented by legal scholars or muftis, and the other by Sufis, it should be viewed as the result of the natural, human tendency of assigning priority to that way which is most suitable for the individual practitioner.

Many legal scholars, Traditionists, and interpreters of the Qur'an produced important books based on the Qur'an and the Sunna. The Sufis, following methods dating back to the time of the Prophet and his Companions, also compiled books on austerity and spiritual struggle against carnal desires and temptations, as well as states and stations of the spirit. They also recorded their own spiritual experiences, love, ardor, and rapture. The goal of such literature was to attract the attention of those whom they regarded as restricting their practice and reflection to the “outer” dimension of religion, and directing it to the “inner” dimension of religious life.

Both Sufis and scholars sought to reach God by observing the Divine obligations and prohibitions. Nevertheless, some extremist attitudes occasionally observed on both sides caused disagreements. Actually there was no substantial disagreement, and it should not have been viewed as a disagreement, for it only involved dealing with different aspects and elements of religion under different titles. The tendency of specialists in jurisprudence to concern themselves with the rules of worship and daily life and how to regulate and discipline individual and social life, and that of Sufis to provide a way to live at a high level of spirituality through self-purification and spiritual training, cannot be considered a disagreement.

In fact, Sufism and jurisprudence are like the two schools of a university that seeks to teach its students the two dimensions of the Shari'a so that they can practice it in their daily lives. One school cannot survive without the other, for while one teaches how to pray, be ritually pure, fast, give charity, and how to regulate all aspects of daily life, the other concentrates on what these and other actions really mean, how to make worship an inseparable part of one’s existence, and how to elevate each individual to the rank of a universal, perfect being (al-insan al-kamil) a true human being. That is why neither discipline can be neglected.

Although some self-proclaimed Sufis have labeled religious scholars “scholars of ceremonies” and “exoterists,” real, per-fected Sufis have always depended on the basic principles of the Shari'a and have based their thoughts on the Qur'an and the Sunna. They have derived their methods from these basic sources of Islam. Al-Wasaya wa al-Ri'aya (The Advices and Observation of Rules) by al-Muhasibi, Al-Ta'arruf li-Madhhab Ahl al-Sufi (A Description of the Way of the People of Sufism) by Kalabazi, Al-Luma’ (The Gleams) by al-Tusi, Qut al-Qulub (The Food of Hearts) by Abu Talib al-Makki, and Al-Risala al-Qushayri (The Treatise) by al-Qushayri are among the precious sources that discuss Sufism according to the Qur'an and the Sunna. Some of these sources concentrate on self-control and self-purification, while others elaborate upon various topics of concern to Sufis.

After these great compilers came Hujjat al-Islam Imam al-Ghazzali, author of Ihya’ al-‘Ulum al-Din (Reviving the Religious Sciences), his most celebrated work. He reviewed all of Sufism’s terms, principles, and rules, and, establishing those agreed upon by all Sufi masters and criticizing others, united the outer (Shari'a and jurisprudence) and inner (Sufi) dimensions of Islam. Sufi masters who came after him presented Sufism as one of the religious sciences or a dimension thereof, promoting unity or agreement among themselves and the so-called “scholars of ceremonies.” In addition, the Sufi masters made several Sufi subjects, such as the states of the spirit, certainty or conviction, sincerity and morality, part of the curriculum of madrassas (institutes for the study of religious sciences).

Although Sufism mostly concentrates on the individual’s inner world and deals with the meaning and effect of religious commandments on one’s spirit and heart and is therefore abstract, it does not contradict any of the Islamic ways based on the Qur'an and the Sunna. In fact, as is the case with other religious sciences, its source is the Qur'an and the Sunna, as well as the conclusions drawn from the Qur'an and the Sunna via ijtihad (deduction) by the purified scholars of the early period of Islam. It dwells on knowledge, knowledge of God, certainty, sincerity, perfect goodness, and other similar, fundamental virtues.

Defining Sufism as the “science of esoteric truths or mysteries,” or the “science of humanity’s spiritual states and stations,” or the “science of initiation” does not mean that it is completely different from other religious sciences. Such definitions have resulted from the Shari'a-rooted experiences of various individuals, all of whom have had different temperaments and dispositions, and who lived at different times.

It is a distortion to present the viewpoints of Sufis and the thoughts and conclusions of Shari'a scholars as essentially different from each other. Although some Sufis were fanatic adherents of their own ways, and some religious scholars (i.e., legal scholars, Traditionists, and interpreters of the Qur'an) did restrict themselves to the outer dimension of religion, those who follow and represent the middle, straight path have always formed the majority. Therefore it is wrong to conclude that there is a serious disagreement (which most likely began with some unbecoming thoughts and words uttered by some legal scholars and Sufis against each other) between the two groups.

When compared with those who spoke for tolerance and consensus, those who have started or participated in such conflicts are very few indeed. This is natural, for both groups have always depended on the Qur'an and the Sunna, the two main sources of Islam.

In addition, the priorities of Sufism have never been different from those of jurisprudence. Both disciplines stress the importance of belief and of engaging in good deeds and good conduct. The only difference is that Sufis emphasize self-purification, deepening the meaning of good deeds and multiplying them, and attaining higher standards of good morals so that one’s conscience can awaken to the knowledge of God and thus embark upon a path leading to the required sincerity in living Islam and obtaining God’s pleasure.

By means of these virtues, men and women can acquire another nature, “another heart” (a spiritual intellect within the heart), a deeper knowledge of God, and another “tongue” with which to mention God. All of these will help them to observe the Shari'a commandments based on a deeper awareness of, and with a disposition for, devotion to God.

#allah#god#islam#muslim#quran#revert#convert#convert islam#revert islam#revert help#revert help team#help#islam help#converthelp#how to convert to islam#convert to islam#welcome to islam#hadith

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jug (Mashraba) with Human-Headed Inscription and Zodiac Signs

Persian, 12th-early 13th century

The Arabic inscription around the neck of this jug is written in a naskh script that terminates in human heads and reads, “Glory, success, dominion, safety, happiness, care, and long life to the owner.” The inscription on the foot reads, “Glory, success, dominion, happiness, safety, intercession, and long life to the owner.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

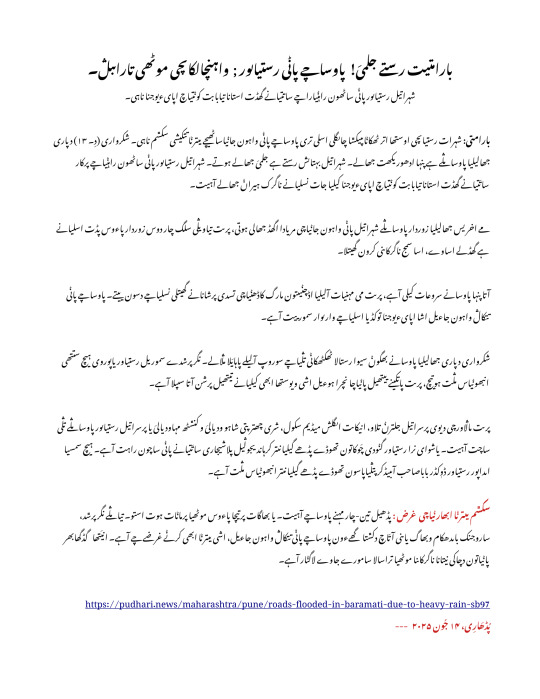

returned to my "Marathi in Arabic Script" idea, re wrote a whole short news article into the new script !

(and a potentially easier to read Naskh version as well)

0 notes

Text

write and Buff-Calligraphy art

Calligraphy art is a beautiful and expressive form of visual art focused on stylized, decorative handwriting or lettering. It often blends the technical skills of penmanship with the creativity of visual design.

Types of Calligraphy Art

Western Calligraphy

Uses Latin scripts.

Tools: broad-edged pens, fountain pens, or brushes.

Styles: Gothic, Italic, Roman, Copperplate.

Arabic Calligraphy

Emphasizes flowing curves and symmetry.

Often used in Islamic art.

Styles: Kufic, Naskh, Thuluth, Diwani.

East Asian Calligraphy

Found in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean traditions.

Brushes and ink on rice paper.

Often considered a spiritual or meditative practice.

Modern Calligraphy

A mix of traditional techniques and contemporary design.

Often used in wedding invites, logos, and digital design.

Freer, more personal and creative.

#calligraphy#calligraphy brush#calligraphy art#calligraphy writing#calligraphy pens#calligraphy fonts#calligraphy style#calligraphy ink

1 note

·

View note

Text

Richard Kimber - Qibla

https://referenceworks.brill.com/display/entries/EQO/EQCOM-00163.xml

Qibla

in Encyclopaedia of the Qur'ān Online

Author: Richard Kimber

(2,861 words)

Full Text

Metadata

Metrics

A direction one faces in order to pray (see prayer ). q 2:142-50 is concerned with the Muslims' qibla and appears to say the following: There is about to be a change of qibla. Foolish people will make an issue of the change and they should be answered with an affirmation of God's absolute sovereignty (q.v.; see also power and impotence ). God has made the believers neither Jews nor Christians (see belief and unbelief; jews and judaism; christians and christianity ) but an example to all, just as the messenger (q.v.) is an example to the believers. The former qibla was instituted only as a test, to see who would follow the messenger's example and who would turn away. It was a hard test but not for those whom God guided (see astray; error; freedom and predestination ). To reward their faith (q.v.) and in response to the messenger's own silent appeal, God will now institute a qibla to the messenger's liking. He and the faithful, wherever they may be, should now turn their faces toward ‘the sacred place of worship’ ( al-masjid al-ḥarām). Both Jews and Christians know that this is the true qibla but no matter what proof of this the messenger might bring them they will never follow his qibla. They cannot even agree on a qibla between themselves. They do as they please but the messenger knows better. In fact they know better, too, but one group of them deliberately conceals the truth. The faithful should turn their faces toward the sacred place of worship so that none but the perverse will have any argument against them. They should not fear ¶ such people but only God who has chosen to bestow on them his favor.

The change of qibla in Muslim tradition

Traditional Muslim exegesis (see exegesis of the qurʾān: classical and medieval ) has provided this passage with a quasi-historical setting in Medina (q.v.). It is commonly reported that when he first arrived in Medina the prophet Muḥammad prayed towards Jerusalem (q.v.) or at least towards Syria (q.v.). This is usually simply stated without any explanation. Occasionally it is noted that Jerusalem was the qibla of the Jews and one report implies that Muḥammad himself chose this direction in order that the Jews might believe in him and follow him (Ṭabarī, Tafsīr, iii, 138). This should not be taken at face value. The purpose of the report is to claim the change of qibla as evidence for the theory of abrogation (q.v.; naskh), which proposes that qurʾānic rulings were sometimes abrogated by later rulings. The report faces the difficulty that whereas the Qurʾān provides an abrogating ruling — the new qibla — it does not easily yield an abrogated ruling, as the theory requires. There is no instruction anywhere in the Qurʾān to pray towards either Jerusalem or Syria. The problem is solved with q 2:115, “To God belong the east and the west. Wherever you turn, there is the face of God (q.v.).” It was evidently on the basis of this permissive ruling that Muḥammad himself chose to pray towards Jerusalem and appealing to the Jews provides a plausible motive for him to do so. A superficially similar report says contrarily that God ordered Muḥammad to pray towards Jerusalem. This pleased the Jews of Medina, though the report does not presume to know that this was God's motive. Muḥammad, we now learn, would have preferred what is here referred to as the qibla of Abraham (q.v.), with the obvious implication that Mecca ¶(q.v.) — and not Jerusalem — was the true focus of the Abrahamic cult. The Jews' initial pleasure is mentioned only to prepare for their subsequent displeasure when the change is made. The point of this report is not now naskh but a simple appropriation of the Abrahamic legacy (Ṭabarī, Tafsīr, iii, 138-9; this and the preceding report are conflated at ibid., ii, 527; see also ḥanīf ). In both reports the circumstantial detail is plainly subordinate to the main point, but on such slight foundations rests the well-established notion that Muḥammad tried to reconcile the Jews of Medina before their perverse ingratitude for his prophetic attentions compelled him to take stronger measures (see prophets and prophethood; gratitude and ingratitude; opposition to muḥammad ).

It is variously reported that the change of qibla came when Muḥammad had been in Medina for two, nine, ten, thirteen, sixteen or seventeen months (Ibn Isḥāq, Sīra, i, 550, 606; Mālik, Muwaṭṭaʾ, i, 196; Ibn Māja, Sunan, i, 322; Ṭabarī, Tafsīr, iii, 132-7; id., Taʾrīkh, i, 1279-81). Most reports of the actual occurrence turn out to be stereotyped vehicles for another theoretical point. The change of qibla by the Prophet himself is not observed directly but reported by a single individual, usually anonymously, who happens to pass by a group of other Muslims in the middle of their prayer. He tells them that the Prophet has now been told to pray towards the Kaʿba (q.v.) or that he has seen him do so, and they immediately turn around and do the same (Mālik, Muwaṭṭaʾ, i, 195; Shāfiʿī, Risāla, 406-8; Bukhārī, Ṣaḥīḥ, i, 110-1, vi, 25; Muslim, Ṣaḥīḥ, i, 374-5; Ṭabarī, Tafsīr, iii, 133-4). The point is to prove for later generations the reliability of khabar al-wāḥid, a report of the Prophet's sunna (q.v.) attributed to only one of his Companions (see companions of the prophet ). It quite deliberately shows the Prophet's own ¶ Companions unhesitatingly changing their practice in the most important religious duty for all Muslims on the evidence of just one of their number. His anonymity supports the point, as it cannot now be argued that a particular Companion was regarded as exceptionally trustworthy. Any Companion would have done and so, we must conclude, does any one Companion whom later generations know through chains of transmitters of ḥadīth (isnāds) as the sole witness to a particular ruling of the Prophet (see law and the qurʾān; ḥadīth and the qurʾān ). There is a report in which Muḥammad himself is observed praying two prostrations (rakʿas; see bowing and prostration ) of the midday prayer (see noon ) towards Jerusalem and then suddenly turning around towards the Kaʿba before completing the prayer (Ṭabarī, Tafsīr, iii, 135). This seems more likely to derive from the forgoing reports than vice versa.

That “the sacred place of worship” is indeed the Kaʿba in Mecca is unquestioned and frequently stated. The foolish people who will question the change are identified as the Jews (several of whom are named in one report) or as the People of the Book (q.v.) or as the hypocrites (see hypocrites and hypocrisy ). The Jews are said to have wanted to seduce Muḥammad away from his religion or were disappointed at losing the satisfaction of seeing him follow their own practice and the hope that he might turn out to be a Jewish prophet after all. The hypocrites just wanted to scoff (Ibn Isḥāq, Sīra i, 550; Ṭabarī, Tafsīr, iii, 132, 134, 138-40, 157-8; see mockery ).

As John Burton has pointed out, there is nothing in the Qurʾān either to prove or to disprove that the former qibla referred to in q 2:142-3 was Jerusalem (Burton, Sources, 179). He might have added, though he does not, that there is nothing in it either to ¶ prove or disprove that the latter qibla, the “sacred place of worship” referred to in q 2:144, was the Kaʿba in Mecca. The historical and geographical referents of q 2:142-50 are known only from Muslim exegesis and it is clear that the exegetes' purpose in examining this passage was not the disinterested satisfaction of historical curiosity (see history and the qurʾān ). The preoccupation with abrogation is pervasive. Al-Ṭabarī (d. 310/923) coolly twists the meaning of q 2:143 so that not the former qibla itself but the change of qibla, the apparently arbitrary phenomenon of abrogation, becomes the test of faith for the believers. This enables him to consider an issue that, for those who assert the reality of the phenomenon of naskh, is theoretically interesting: namely, whether those believers who lived and died under the abrogated ruling will be rewarded in the same way as those who survived to obey the new one (Ṭabarī, Tafsīr, iii, 163-70). Why some should have found it hard to pray towards Jerusalem, if that was indeed the former qibla, is not a question he raises.

For all that, it seems clear from the text that q 2:142-50 is a residue of the process by which Islam asserted its independence as the one true religion (q.v.) from its Jewish and Christian antecedents (see religious pluralism and the qurʾān ). This becomes clearer still when the passage is examined, as Burton (Sources, 171-3, 179-83) has shown, in its larger context. q 2 as a whole is intensely polemical, with sustained attacks on the authenticity of the Jewish religion and in particular the Jewish claim of continuing adherence to God's covenant (q.v.) with Abraham. It stakes Islam's own claim to the covenant through Ishmael (q.v.) and prepares the ground for q 2:142-50 with an account of Abraham's foundation, with Ishmael's help, of a sanctuary as a place of prayer and ritual ¶(q 2:125-8; see ritual and the qurʾān ). This Abrahamic sanctuary is referred to only as “the house” or “my (God's) house” but is easily identified with “the sacred place of worship” (al- masjid al-ḥarām) of q 2:142-50 or the qibla of Abraham as the exegetes call it (see house, domestic and divine ). At q 3:96 this sanctuary is said to have been at Bakka, which everyone has been taught is an old name for Mecca. Even if that might be doubted, the polemical context at both q 3:96 and q 2:125-8 makes almost inescapable the implication that, wherever it was, the Qurʾān's Abrahamic sanctuary was definitely not in Jerusalem. To that extent the exegetes' identification of the abrogated qibla with Jerusalem makes obvious sense of the text.

The fundamental issue behind the polemic of q 2 is the problem of changing the law within a monotheistic intellectual tradition which insists that the law is God's law and that God's law is immutable. The problem and some of its solutions are older than the Qurʾān but the solution seen in q 2:142-50 is the most typically qurʾānic one. The new qibla is not an innovation (q.v.) but a restoration. If it differs from the practice of Jews and Christians, it is the latter who have arbitrarily departed from what they themselves know, but will never admit, is the truth. The heat of qurʾānic polemic against the Jews in q 2 is a smokescreen for this sleight of hand (see polemic and polemical language ). Whereas for early Christianity the crux issue with Judaism was the Sabbath (q.v.), for early Islam it was evidently the qibla. Once the crux is overcome (in q 2:142-50), the way is open for the rush of new legislation that follows in the remainder of the sūra.

The early qibla in history

Whether the early Muslims ever did pray towards Jerusalem we shall probably never ¶ know. In 1977 Patricia Crone and Michael Cook proposed that they did once pray towards a sanctuary somewhere in north-western Arabia. Their evidence, reviewed in detail by Robert Hoyland in 1997, is firstly that two Umayyad mosques in Iraq, one at Wāsiṭ and one at Iskāf Banī Junayd, are known from modern archeological investigation to have been oriented in a westerly direction much further north than that of Mecca. Secondly, there are reports in Muslim literary sources that the first mosque built in Egypt was oriented in an easterly direction that was also further north than that of Mecca. In addition, Jacob of Edessa, a seventh century c.e. Syrian Christian writer, says that Jews and Muslims in Egypt prayed to the east and in Babylonia to the west (Crone and Cook, Hagarism, 23-4; Hoyland, Seeing Islam, 560-73; see mosque ).

Put together, these fragments of evidence are suggestive — but if each fragment is considered separately none is very persuasive. The archeological evidence tells us nothing of the early mosque builders' intentions unless we know how accurate their technical means of putting their intentions into effect were. As David King (Ḳibla, 87-8) has argued, it is likely that the earliest mosque builders adopted a local convention rather than a scientifically exact direction for the Kaʿba. In the case of the mosque of Iskāf Banī Junayd, the archeological report of its misorientation observes, “the error seems to have been aggravated by the fact that the line of the Nahrawan (Canal) clearly influenced and dictated that of the mosque in large degree” (Creswell, Short account, 268). Muslim literary reports that the first mosque in Egypt was orientated too far to the north put it down to a personal idiosyncrasy of the Muslim commander and conqueror of Egypt ʿAmr b. al-ʿĀṣ, who oversaw its con- ¶ struction. They note that other worshippers in the mosque used to turn themselves off to the south until the mosque itself was finally rebuilt and realigned (see also science and the qurʾān ).

Literary evidence also needs to be judged against the possibility that the writer is working with a simplified and schematic mental map. Jacob of Edessa's point about Muslims is that they do not pray everywhere in the same geographical direction. They pray towards the Kaʿba, so that in Egypt they pray to the east, in Babylonia to the west, from south of the Kaʿba to the north, and in Syria to the south. Does this really help us to locate the Kaʿba? It is equally likely that Jacob himself, for the sake of simplicity, reported only approximately what he had actually observed or that Muslims in all those parts of the world prayed in any case only approximately in the direction of Mecca. In the end, it may not be significant where exactly their approximate direction happened to lie.

Richard Kimber

0 notes

Text

The role of Hadith in shaping Islamic law (Sharī‘ah) is foundational and multifaceted. Here is a structured overview of its importance:

---

1. Definition of Hadith

Hadith refers to the recorded sayings, actions, approvals, and descriptions of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him). It complements the Qur'an and serves as the second primary source of Islamic law.

---

2. Hadith as an Explanation of the Qur’an

Many Qur’anic commands are general or brief; the Hadith explains, specifies, and details them.

Example: The Qur’an commands prayer (ṣalāh) but does not explain how to perform it. The Hadith provides the details of its times, units (rakʿāt), and exact form.

---

3. Source of Independent Legislation

The Prophet (PBUH) was authorized by Allah to legislate in matters not directly addressed in the Qur’an.

Qur’an 59:7 — “…And whatever the Messenger has given you – take; and what he has forbidden you – refrain from…”

Scholars derive rulings from authentic Hadith even when no Qur’anic verse exists on the matter (e.g., inheritance of grandmother, punishment for drinking alcohol).

---

4. Basis for Legal Schools (Madhāhib)

All four major Sunni schools (Ḥanafī, Mālikī, Shāfiʿī, Ḥanbalī) rely heavily on Hadith.

Jurists (fuqahā’) use Hadith to:

Extract legal maxims.

Reconcile conflicting evidence.

Determine abrogation (naskh) where later Hadith override earlier rulings.

---

5. Conditions for Legal Use of Hadith

Not every Hadith is used in lawmaking; it must be:

Authentic (ṣaḥīḥ) in chain and content.

Not contradicted by stronger evidence.

Applicable in legal contexts.

---

6. Hadith and Ijtihād

Hadith is essential in ijtihād (independent reasoning).

Jurists analyze Hadith to derive rulings for new situations while staying within Sharīʿah principles.

---

7. Preservation and Authentication

The science of Hadith (ʿilm al-ḥadīth) developed to rigorously verify chains of narration (isnād) and text (matn), ensuring that only trustworthy reports are used in law.

---

Conclusion

The Hadith plays a central role in shaping Islamic law by clarifying the Qur’an, serving as a source of legislation, guiding juristic reasoning, and preserving the Prophet’s practical application of divine guidance. Without Hadith, much of Islamic law would be incomplete or unclear.

0 notes

Note

Hiii, I've been following your blog since some time. And I've been very fascinated and impressed by your journey. I'm sure at this point you know hindi better than me (I'm not proud of this, I'll focus better on Hindi from now). And I've always had this question, I'm not sure if I asked you or if you have already answered it or not. But how did you start learning Hindi? Are you Indian or indian origin? And how has your journey been? Did you find difficulties? What was easy for you and what did you like/dislike about the culture as you continued learning the language? I'm very curious.

Hi and thank you so much for such a nice ask!

Here's my previous answer to how I got into Hindi in the first place.

In short, I am just a Finnish linguaphile with no connection to India or South Asia whatsoever. I have loved learning about different languages since childhood but Hindi (and Urdu on the side) has been my passion for the past six to seven years now.

I got into the language very typically through Hindi cinema but more than just the aesthetics I'm fascinated by the history, art, socio-political fabric, nature and just all of it. I love learning new things in general and there's always something new about Indian people or culture that draws my interest. Looking at things - whether political, religious or whatever - from a distance, I try to observe and form an understanding more than form opinions - it's not my place and all I have is endless respect for Indian people. I've never been to India but believe me I have long to-do and to-see lists when I eventually one day get to go there.

My language journey has been very enjoyable. I've done some online courses, had iTalki tutors, done some videos to practice pronunciation, made a huge Anki deck and done lots of reading, podcast listening and film watching. I was making great progress but my learning has been on somewhat hiatus since last autumn when I got a new job that took all my energy. Since January I've been writing a PhD thesis proposal that has taken all my spare time and my Hindi learning has diminished to scrolling Tumblr poems and listening to film songs while commuting. The passion is still there and I intend to return to my routines as soon as possible.

What I love most about Hindi as a language is the logic of it. It's - for me at least - very easy to 'get' Hindi, as in understanding the grammar rules - why things are the way they are. Hindi is a very learner-friendly language that way. A bigger issue is the immense vocabulary and understanding of the historical and cultural roots around borrowing sounds and words from Sanskrit, Persian and other languages - how they play together and how they do not etc. When learning Hindi you are never just learning Hindi!

I had some trouble learning Devanagari at first and learning to differentiate all the sounds (and produce them from my mouth). It took time, but one day they clicked. I'm not perfect and there's a lot of room for improvement but seeing the progress I've made is very encouraging and helps me keep on learning. Learning Nastaliq and Naskh is another story - and another journey altogether!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Best Arabic Fonts: The Ultimate Guide for Designers and Creators

If you’re a designer or creator diving into the world of Arabic typography, you’re in for a ride that blends tradition, beauty, and modern flair. Arabic fonts aren't just typefaces but visual storytellers rooted in centuries of culture and artistry.

What Are Arabic Fonts?

Arabic fonts are typefaces designed to display the Arabic script, which flows from right to left and includes a unique set of characters. These fonts are used in everything from branding and signage to websites, books, and calligraphy artwork.

Why Arabic Fonts Matter in Design

Think about it—would a luxury perfume brand use Comic Sans in its Arabic branding? Of course not. The right Arabic font sets the mood, reinforces the brand, and makes content not just readable but beautiful.

Types of Arabic Fonts

Arabic typography has both traditional and contemporary faces. Let's break down the main styles.

Traditional Arabic Fonts

These are your classic, calligraphy-inspired fonts. They're deeply rooted in history and religious manuscripts.

Naskh

Naskh is the workhorse of Arabic scripts. It’s clean, readable, and perfect for body text in print and digital media.

Ruq'ah

Ruq'ah is simple and quick to write — think of it as the Arial of handwritten Arabic. Great for headlines and notes.

Modern Arabic Fonts

Modern fonts offer fresh takes on traditional scripts or entirely new creations that merge Arabic and Latin styles.

Kufi

With its geometric and blocky appearance, Kufi is widely used in logos and display designs. It’s bold, structured, and eye-catching.

Diwani

Elegant and decorative, Diwani script is your go-to for wedding invitations and formal documents. It’s like cursive, but fancier.

The Art and History Behind Arabic Calligraphy

Arabic fonts are more than digital assets — they’re descendants of centuries-old art. Arabic calligraphy developed as a way to beautifully present the Quran, evolving into several scripts across regions and time. Using Arabic fonts is like echoing the brushstrokes of history, pixel by pixel.

How to Choose the Right Arabic Font

Choosing the right font is part science, part gut feeling. Here’s how to make that decision easier.

Purpose of the Design

Ask yourself: is this for a logo, a book, an app, or a t-shirt? Bold and stylized fonts work great for logos, while clean scripts suit body text.

Readability and Aesthetics

No matter how pretty a font is, it has to be legible. Avoid overly decorative fonts for paragraphs and use them where flair is needed — like headlines.

Top Free Arabic Fonts You Can Download Today

Let’s talk freebies — these top Arabic fonts are not just high-quality, but totally free to download and use.

1. Amiri

Inspired by traditional Naskh, Amiri is perfect for books and long reads. It’s classy, easy to read, and has a timeless feel.

2. Cairo

A modern sans-serif Arabic font that pairs beautifully with Latin sans-serifs. Think of it as Helvetica’s Arabic cousin.

3. Noto Naskh Arabic

Designed by Google, it ensures uniformity across platforms and is super clear at small sizes.

4. Mada

Sleek, modern, and perfect for interfaces and digital content. It blends traditional curves with a minimalist touch.

5. Reem Kufi

An all-caps Kufi style font that’s bold and great for titles. It screams attention in the best way possible.

Where to Download Arabic Fonts for Free

No need to search forever—here are your go-to sites.

Best Websites for Free Arabic Fonts

Google Fonts – Great for modern, web-safe Arabic fonts.

Font Squirrel – Curated fonts with commercial licenses.

DaFont – Tons of decorative and thematic Arabic-style fonts.

FreeFontDownload.com – A hub for high-quality Arabic fonts, perfect for personal and commercial projects.

Tips for Using Arabic Fonts in Design Projects

Fonts can make or break your design. Here’s how to make sure they elevate your project.

Font Pairing Strategies

Try mixing an elegant Arabic script with a clean Latin sans-serif for bilingual designs. Contrast is your friend here.

Ensuring Compatibility Across Devices

Always test your font across devices and browsers. Some older devices may not support newer Arabic font files properly.

Common Mistakes to Avoid When Using Arabic Fonts

Using Latin-inspired fonts in Arabic designs it looks out of place.

Ignoring kerning and spacing, Arabic needs careful attention to how letters connect.

Overusing decorative fonts — beauty is in balance.

Future Trends in Arabic Typography

Arabic fonts are moving beyond traditional constraints. We’re seeing more variable fonts, bilingual type systems, and even experimental fonts that bend the rules for creative projects. The future is bright and bold.

Conclusion

Arabic fonts are more than just text—they’re a dance of culture, design, and communication. Whether you're designing a logo, writing a blog, or creating a poster, the right Arabic font sets the tone. With tons of free options available, now’s the perfect time to explore and play with typography. Just remember—beauty and function should go hand in hand.

0 notes

Text

Archäologische Sammlerstücke erzählen die Geheimnisse der ägyptischen Geschichte.

Diese Tradition steht im Zusammenhang mit den Bemühungen der Museen, ihre kulturelle und pädagogische Rolle zu stärken und das archäologische Bewusstsein in allen Teilen der Gesellschaft zu schärfen. Sie können die besten Reisen buchen, indem Sie ÄGYPTEN-REISEPAKETE empfehlen, Ägypten-Websites zu besuchen.

Die am meisten ausgewählten Stücke in den Museen Ägyptens:

Museum für islamische Kunst - Bab al-Khalq: Zeigt einen Krug und eine mit Gold und Silber überzogene Kupferschale, die dem Mamlukenprinzen tabtaq gehören und mit Inschriften in Naskh-Schrift und den Titeln des Prinzen verziert sind. Buchen Sie jetzt Ihre Tour 2 Tage Kurzurlaub in Kairo, um die bekanntesten monumentalen Sehenswürdigkeiten Ägyptens zu besuchen.

Koptisches Museum-altes Ägypten: Präsentiert eine Sammlung von Töpferöfen, die zur Konservierung von Wasser verwendet wurden, Mohammed Ali Palace Museum-Al-maneel: Hebt die Salsabil-Halle hervor, in der sich Marmorbrunnen mit prächtigen geometrischen Mustern befinden, die die Architektur des XIX. Jahrhunderts widerspiegeln. Verbringen Sie Ihren Urlaub mit Ihrer Familie, indem Sie einen 3-tägigen Zwischenstopp in Kairo buchen, um einen fantastischen Urlaub zu verbringen.

Nationales Polizeimuseum - Zitadelle: Zeigt ein hölzernes Modell eines Bootes mit zehn Seeleuten, das die Flusspolizei im alten Ägypten darstellt. Sie können Ägypten durch ÄGYPTEN-TOUREN besuchen, die von Kairo Top Touren angeboten werden.

Das Museum für königliche Fahrzeuge - Boulak: Es umfasst ein Ölgemälde von Prinzessin Fawzia, Tochter von König Ahmed Fouad I., die eine Krone und ein Netzset trägt, das vom Pariser Haus "Van Cleve & erpels" entworfen wurde. Sie können die besten Ausflüge durch 3 Tage Kairo Kurzurlaub buchen, um diesen großartigen Ort zu erkunden.

Gayer Anderson Museum-Frau Zeinab: Zeigt die Krone einer Steinsäule mit einer Statue der Göttin Hathor, einem Symbol für Liebe und Mutterschaft im alten Ägypten. Buchen Sie jetzt Ihre Tour von Kairo Städtereise 2 Tage, um die große Statue zu sehen.

Emhotep Museum-Sakkara: Zeigt eine Sammlung von chirurgischen Bronzeinstrumenten, die die Entwicklung der Medizin im alten Ägypten widerspiegeln. Sie können Ägypten durch Städtereisen in Kairo 3 Tage besuchen, um die alten architektonischen Entwürfe zu sehen.

Kairo International Airport Museum-Terminal 2: präsentiert eine hölzerne Ikone der Heiligen Cosmas und Damian, der ältesten christlichen Ärzte, die sich durch heilende Krankheiten auszeichneten. Sie können die besten Reisen durch ÄGYPTEN KLASSISCHE TOUREN mit den besten Preisen von Kairo Top Tours buchen.

Alexandria Nationalmuseum: Eine seltene Statue von Königin Hatschepsut mit weißer Krone und falschem Bart sticht hervor und spiegelt ihre einzigartige Position als erste Frau wider, die Ägypten mit voller Autorität regierte. Königliches Schmuckmuseum-Alexandria: Königin Faridas Blumenkrone aus Platin, die mit einzigartigen Diamanten besetzt ist, ist ausgestellt. Sie können Ägypten durch 4 Tage Kairo Städtereise besuchen, um diese großen Paläste zu sehen.

Griechisch-römisches Museum-Alexandria: Es umfasst eine Marmorstatue des Gottes Asklepios, das Symbol der Medizin bei den Griechen und Römern, die einen Stock hält, der von einer Schlange umwickelt ist, die nicht Sie ist auch heute noch ein Symbol der Medizin. Buchen Sie jetzt Ihre Tour Kairo Kurzurlaube Pakete, um das schöne Wetter in Ägypten zu genießen.

Luxor Museum für altägyptische Kunst: Zeigt ein Steinfragment, das Königin Hatschepsut darstellt, die dem Gott Amun Opfergaben darbringt , Mumifizierungsmuseum-Luxor: Beherbergt eine Sammlung chirurgischer Werkzeuge, die beim Mumifizierungsprozess verwendet werden, wie z. B. Meißel und Löffel, die beim Reinigen von Organen verwendet werden Innenraum. Buchen Sie jetzt Ihre Tour mit Städtereise nach Kairo in 5 Tagen, um diese erstaunliche Stätte zu erkunden.

Nubia Museum-Assuan: zeigt eine Granitstatue von Prinzessin Amunardis I., Tochter von König Kashta und Schwester von König Baankhi, der eine prominente Figur in der fünfundzwanzigsten Dynastie war. Sie können die besten Ausflüge von Kairo Kurzurlaub in 4 Tagen buchen, um diesen großartigen Ort in Assuan zu erkunden.

@cairo-top-tours

0 notes