#Phenomenology of the Body

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Philosophy of the Skin

The philosophy of the skin examines the role of the skin as a boundary, both physically and metaphorically, and its significance in human experience, identity, and interpersonal relationships. Skin, as the body’s largest organ, plays a fundamental role in how we perceive the world through touch, how we differentiate between self and other, and how we present ourselves socially. In philosophical discourse, the skin represents the interface between the individual and the external world, highlighting themes of vulnerability, intimacy, identity, and embodiment.

Key Themes in the Philosophy of the Skin:

Skin as a Boundary:

The skin acts as a physical boundary between the internal and external worlds, defining the limits of the body. It marks the division between self and other, playing a significant role in questions of identity and individuality.

Philosophers of embodiment like Maurice Merleau-Ponty explore how the skin is more than just a barrier; it is also a point of contact through which we experience the world. The skin mediates our sensory experiences, particularly through touch, grounding us in the physical environment and facilitating connection with others.

Touch and Sensory Perception:

Skin is the primary organ for touch, one of the most intimate senses. Philosophically, touch is often seen as a more immediate and embodied form of perception than sight or hearing, engaging us directly with objects and people.

Haptic perception—the way we understand the world through touch—raises philosophical questions about how we experience physical objects and other human beings. For instance, while vision can create a distance between the observer and the observed, touch collapses that distance, offering a more direct form of interaction.

The Skin and Vulnerability:

The skin's role in protecting the body highlights its vulnerability. The skin can be wounded, scarred, or marked, making it a symbol of human fragility. Philosophers like Emmanuel Levinas have explored the ethical significance of this vulnerability, particularly in relation to our interactions with others.

Levinas argued that vulnerability, especially as it is revealed through the skin, creates an ethical demand for care and responsibility toward others. The skin’s exposure symbolizes the openness of human beings to harm but also to intimacy and ethical connection.

The Skin and Identity:

Skin is central to how individuals are identified and categorized socially. Skin color has been a focal point of philosophical discussions about race, racism, and identity. Frantz Fanon, in works like Black Skin, White Masks, explored how skin color shapes experiences of alienation, power, and oppression in colonial and postcolonial contexts.

Skin also functions as a canvas for self-expression, through tattoos, piercings, scars, and other modifications, making it an important site for exploring questions of personal identity and social belonging.

The Skin and Embodiment:

The skin is central to philosophical discussions on embodiment, which considers the body as lived experience rather than as an object. Phenomenologists such as Merleau-Ponty argue that our sense of self is inseparable from our embodied experience, of which skin is a crucial element.

Our skin is constantly in contact with the environment, making it essential for experiencing the world in a bodily way. This lived experience of the body—feeling warmth, cold, pleasure, pain—demonstrates how we are constantly engaged with the world through our skin, which both protects us and connects us to the environment.

Skin and Aesthetics:

The skin has long been associated with beauty and aesthetics. In many cultures, the smoothness, color, and texture of skin are central to standards of beauty, prompting reflection on how aesthetic judgments are influenced by bodily appearances.

The artificial modification of skin—such as cosmetics, plastic surgery, and body art—raises philosophical questions about the authenticity of appearance and the extent to which the skin serves as a medium for aesthetic expression.

Skin as a Metaphor:

In addition to its physical properties, skin serves as a powerful metaphor in philosophy and literature. To "be thick-skinned" or "thin-skinned" refers to one's emotional resilience or sensitivity, linking the physical properties of skin to psychological traits.

The metaphor of "wearing a mask" or "shedding skin" is often used to describe changes in identity or emotional states, suggesting that the skin is not just a boundary but a dynamic interface that can reflect and shape one’s psychological and social self.

Skin and Intimacy:

The skin is crucial for human intimacy. The act of touching—whether a handshake, an embrace, or a caress—is a deeply symbolic gesture that expresses trust, affection, or solidarity. Touch is one of the most immediate ways of creating a connection with others.

The philosophy of touch emphasizes how the skin facilitates communication without words, enabling a form of non-verbal interaction that is powerful in both personal relationships and ethical encounters.

Ethics of Care and Skin:

Skin care, both in a literal and metaphorical sense, is related to the ethics of care. Taking care of one’s skin, or the skin of others, embodies broader principles of responsibility, nurturing, and maintaining well-being. In health care, for example, caring for someone’s skin can symbolize larger commitments to their dignity and comfort.

The Skin and Technology:

The development of technologies that interact with the skin—such as wearable devices, prosthetics, or virtual reality haptics—raises philosophical questions about the boundary between the organic and the artificial. How do these technologies reshape our understanding of skin as a human organ?

As the skin becomes more integrated with technology, its role as an interface between the self and the world becomes more complex, inviting discussions about cyborg philosophy and the future of human embodiment.

The philosophy of the skin touches on fundamental questions about identity, vulnerability, sensory perception, and human relationships. Skin, as a sensory organ and boundary, plays a pivotal role in how we experience and interpret the world. Through its capacity to feel, protect, and express, the skin is a rich site for philosophical inquiry, connecting the physical body to broader existential, ethical, and social concerns.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#education#chatgpt#ontology#metaphysics#psychology#Embodiment and Sensory Perception#Touch and Intimacy#Identity and Skin#Vulnerability and Ethics#Skin and Aesthetics#Phenomenology of the Body#Skin and Technology#Race and Skin

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Phenomenology of the Body

Phenomenology (contents of consciousness) of the Spirit was introduced by Hegel and I diverge from his creation to the phenomenology of the body. Instead of phenomenology of the spirit I introduce Senseonciousness (from sense and consciousness) and senseonciousness satisfies the experience of the body. All information is gathered and processed by the senses and they can objective and subjective experiences. Objective consciousness is the sense datum registered the mind. It can also be called empirical consciousness. For example, I observe a table and it becomes part of sensational consciousness. It becomes a fact registered in the mind. Objective consciousness involves perception and cognition. Subjective consciousness on the other hand is lyrical, poetic and sublime. What is lyrical consciousness? It’s the recognition of the self as a perfect being. It’s the self-pampered with love. It’s metaphoric allusion with positive affirmation. It’s a body having in-the-body experiences. It’s a saturation of pathos. A poetic consciousness is the amour felt by the body. It’s the nectar of love. It’s a poem of ecstasy. It’s a lyrical beatitude. It’s the language of music. It’s a cherub greeting of a lover. It’s an art of copulation. What is sublime consciousness? It’s a positive affirmation of consciousness. It’s an earthindence (earth and transcendence).

#Anand Bose#Hegel#Literature#Literary theory#Philosophy#Phenomenology#Phenomenology of the body#Geist#Aesthetics#Art#Senseonciousness#Earthindence

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ebenezer Scrooge: "Tight as a drum!"

Ghost of Christmas Present: "They can't hear you."

163K notes

·

View notes

Text

Control and the Body — Biological, Physical, and Environmental Interactions - Post 4 of 5

The human body, with its intricate network of systems and interactions, stands as a profound testament to the concept of control—yet it is also an enduring reminder of its limitations. Photo by JESHOOTS.com on Pexels.com From the autonomic regulation of heartbeat and respiration to the conscious control of movement and expression, our experience of embodiment is one of constant negotiation…

View On WordPress

#biohacking#biological control#biotechnology ethics#bodily mastery#body and mind#Buddhist philosophy#ecological health#environmental connection#genetic engineering#health culture#homeostasis#indigenous health#mind-body dualism#Neuroplasticity#phenomenology of perception#physical control#Qi Gong#Raffaello Palandri#somatic awareness#Stoicism#Tai Chi#transhumanism

1 note

·

View note

Text

read a paper for my essay ive known about this essay for 6 weeks its due in 3 ish weeks say well done !!!!!

#kankum#onto the next one#i need to do well!!!!!!!!!!!#i got 75 in my last essay in this module#and the module is split w two lecturers#and the other lecturer was rlly good#but im Obsessed with this lecturer#and i want them to be impressed w my essay#pls like my gender transition as body project phenomenology essay [redacted]

1 note

·

View note

Text

Theories of the Philosophy of Expression

The philosophy of expression explores the nature, significance, and implications of human expression in various forms, including language, art, music, and body language. It delves into questions about the origins of expression, its relationship to identity, culture, and society, and its role in human communication and understanding. Additionally, it examines ethical and aesthetic considerations surrounding expression, as well as the philosophical frameworks that underpin different modes of expression.

The philosophy of expression encompasses various theories and perspectives that seek to understand the nature and significance of human expression. Some prominent theories include:

Mimetic Theory: This theory, proposed by Plato and Aristotle, suggests that art and expression imitate or reflect reality. It emphasizes the role of art in representing the natural world and conveying universal truths.

Expressivism: Expressivism posits that expression, particularly in language and art, serves as a means for individuals to express their inner thoughts, emotions, and experiences. It emphasizes the subjective and personal aspect of expression, focusing on the individual's unique perspective.

Semiotics: Semiotics, developed by Ferdinand de Saussure and Charles Peirce, explores the study of signs and symbols and their interpretation. It examines how meaning is conveyed through linguistic and non-linguistic signs, highlighting the role of context and cultural conventions in interpretation.

Pragmatism: Pragmatist philosophers like John Dewey emphasize the practical consequences of expression. They argue that expression serves a functional purpose in communication and problem-solving, shaping social interactions and facilitating collective action.

Hermeneutics: Hermeneutics focuses on the interpretation of texts and cultural artifacts, including literary works, religious texts, and artistic expressions. It examines the process of understanding and meaning-making, considering the role of context, tradition, and the interpreter's perspective.

Aesthetic Theory: Aesthetic theories, developed by philosophers like Immanuel Kant and Arthur Schopenhauer, explore the nature of beauty and artistic experience. They examine how aesthetic judgments are formed, the criteria for evaluating art, and the relationship between art and morality.

Phenomenology: Phenomenological approaches, as developed by Edmund Husserl and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, explore the lived experience of expression. They focus on the first-person perspective and the embodied nature of expression, examining how individuals perceive, interpret, and engage with the world through expression.

These theories offer diverse insights into the complexities of human expression, highlighting its multifaceted nature and its significance in shaping individual and collective experiences.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#chatgpt#education#ontology#metaphysics#psychology#Philosophy of language#Philosophy of art#Philosophy of music#Body language#Communication#Identity#Culture#Aesthetics#Ethics#Human experience#Mimetic theory#Expressivism#Semiotics#Pragmatism#Hermeneutics#Aesthetic theory#Phenomenology#Interpretation#Meaning-making

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any underrated recommendations for feminist texts? Books, articles, even blog posts and the like

very broad category and I’m not sure what counts as underrated so just have an assortment of things I have found interesting over the years, these are all fairly easy to search for and/or SciHub though I'll try to add links when I can.

Ellen Willis, “Radical Feminism and Feminist Radicalism.” This is the perspective of a radical feminist (one of the founders of Redstockings alongside Firestone), reflecting on the movement’s shape as of ‘84, in which she identifies and criticizes its ‘cultural feminist’ pivot, as well as the problems within the radical feminist political movement that made that pivot possible, if not inevitable. Hits pretty hard these days, kind of my go-to in terms of articulating why a “radical feminism (TM)" sans transphobia isn’t worth fighting for.

Iris Marion Young, "Throwing Like a Girl." Really transcendent work of feminist phenomenology exploring how women's bodily comportment is governed by certain socially constructed imperatives, with an interesting critique/corrective of Beauvoir.

Lydia Sargent (editor), Women and Revolution: A Discussion of the “Unhappy Marriage.” This is a collection of essays by prominent scholars about the relationship of patriarchy and capitalism or of feminism and Marxism/socialism, including Lise Vogel and Iris Young, starting with a Hartmann paper that is considered foundational to this question. A good supplemental or alternative would be the first two chapters of Cinzia Arruzza, Dangerous Liaisons.

Heather Berg, "Reproductivism and Refusal." A critique of the veneration of "feminized" and "reproductive" work and how this operates under the rule of capital.

Kirstin Munro, "Unproductive Workers and State Repression." Discussion of how certain forms of "unproductive" and feminized work, especially those employed by the state or state-backed institutions (nurses, social workers, teachers), participate in the reproduction of the capitalist totality.

Katie Cruz, “The Work of Sex Work.” One of the more robust treatments of this issue, and does a good job of avoiding the Scylla of libertarian contractarianism and the Charybdis of MacKinnonite liberalism.

Margot Canaday, The Straight State. History of the development of the American administrative state's treatment of homosexuality and how this became a major object of statecraft in the twentieth century.

Perhaps you already are familiar, it’s very beloved in some spheres, but Susan Stryker, “My Words to Victor Frankenstein” is deeply moving.

I have also generally enjoyed the bodies of work of Kathi Weeks (anti-work feminism), Dorothy Roberts (racecraft and its relationship with misogyny), Sara Ahmed (affect theory and feminist ethics/phenomenology), Talia Mae Bettcher and Sally Haslanger (both social ontology of gender), and Florence Ashley (transfeminist legal analysis).

249 notes

·

View notes

Text

(some) of ur hi3rd favs and a philosophy text related to how i view their characters. resolution got nuked so here's a quick explanation of each - Kiana - A Thousand Plateaus (G. Deleuze & F. Guattari) Everything is flows and connections that can be assembled and reassembled in infinite ways, and stable identity is just a temporary crystallization of forces. Mei - Fear & Trembling (S. Kierkegaard) True faith means choosing what you love over what society calls ethical, a choice so personal you can't even explain it to others. Bronya - Phenomenology of Perception (M. Merleau-Ponty) We understand the world through our body's lived experience, not through abstract thought separated from physical existence. Fu Hua - The Myth of Sisyphyus (A. Camus) We all know this one from the memes, her whole shtick is very sisyphean lol Himeko - The Ignorant Schoolmaster (J. Rancière) Anyone can learn anything because intelligence is equal in all people; the role of teaching is to awaken will, not transmit knowledge. Welt - Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (L. Wittgenstein) The limits of language are the limits of the world. Otto - Thus Spoke Zarathustra (F. Nietzsche) We must create our own values and become who we truly are, even if it means standing alone against everyone. Kevin - Philosophy of History (G.W.F Hegel) History is a rational process where humanity progresses through conflict and suffering toward absolute knowledge/freedom. Elysia - Minima Moralia (T. Adorno) In a totally broken world, the only honest philosophy is fragmentary reflections on how to preserve some trace of human happiness despite everything.

#mihoyo#honkai impact 3rd#coal#unfunny#hi3rd#kiana kaslana#raiden mei#bronya zaychik#fu hua#himeko#welt yang#otto apocalypse#kevin kaslana#elysia

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of my favourite things about RTD's writing, and probably why he's having so much fun writing god/god-like characters, is his really good grasp of the tension between the essence and the form. Like, you can almost feel him poking with his finger in some unfathomable depth, looking at what's under his fingernail and wondering hm, now how would you present yourself to intelligent life in specific space and time. There's a lot of atheistic appreciation of social functions of religion to it, studying it like a bug in a jar, and also how it gets misinterpreted (think mr Copper looking at Euroatlantic christmas and figuring out it's about cannibalism). It's this sort of, sorry for allusion, idea of family gathering watching tv as the contemporary version of worshipping the hearth, a shopping mall as the temple of consumption, concept of death taking on the form of what happens to be worshipped as embodiment of death.

I think this was put to particularly good use with the Toymaker, where he also reinterpreted the character's original racist feel by making the parodic Mandarin just one among a French mime, German shopkeeper, English tin soldier and American pilot, all national stereotypes as toys. Mr Ring-a-Ding/Lux Imperator, the whole concept of cinema as worship of light, like is it really a coincidence that the episode aired on Easter Vigil (coincidentally same day in both western and eastern churches), the worship of resurrecting light yes I'm saying Alan Cumming played evil 2D Christ.

And this is what I keep saying about his writing of the Master, it's less the case of "he's just a misogynist prick" only of "what would the character whose whole shtick is power be like in the era of postpolitics", like really, Harold Saxon has less to do with Tony Blair than with Silvio Berlusconi. But it's also the case with the Doctor, this whole "what would it be like to have the knowledge of all of pasts and futures while in bodies tailored to the tastes of 2000s and 2020s teens".

It's not the matter of there's performance and then there's the essence, only of performance is the essence, form shapes the meaning, medium is the message, etc.

Basically, RTD seems to be having a lot of fun putting almighty gods in the bodies of old half blind turtles, and I think it's beautiful and also I so very deserve a grant to write a book about phenomenology of religion in mass culture.

#doctor who#doctor who spoilers#doctor who meta#dw meta#russel t davies#the doctor#tenth doctor#fifteenth doctor#the master#simm!master#the toymaker#sutekh#mr ring a ding#lux imperator

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is a growing consensus in transgender studies that trans embodiment is not exclusively, or even primarily, a matter of the materiality of the body. Where one locates a “transsexual real,” whether phenomenologically, in the practices (social, medical, legal, and so on) of transition, in narrative, via the cinematic, or even in the unspeakable and unrepresentable aspects of imaging transness, shifts in relation to racial blackness.

In apposition with transness, blackness, as, among other things, the capacity to produce distinction, has come to structure modes of valuation through various forms, producing shadows that precede their constituting subjects/objects to give meaning to how gender is conceptualized, traversed, and lived.

As the media narratives of Hicks Anderson, Black, the Browns, and McHarris/Grant shed light on the negativity of value, exposing how the notion is produced in an alchemy of black criminalization, violence, disappearance, and death, they also illustrate—albeit circumscribed in their partiality—other ways to be trans, in which gender becomes a terrain to make space for living, a set of maneuvers with which blacks in the New World had much practice.

Black On Both Sides- C Riley Snorton

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

World Tai Chi and Qigong Day

World Tai Chi and Qigong Day serves not merely as a calendar annotation but as a global synchronous event, a resonant node within the ever-expanding network of embodied contemplative and martial traditions. Its emergence on the global stage is a powerful testament to the enduring efficacy and cross-cultural permeability of practices rooted deeply in Chinese history and philosophy. Approaching…

View On WordPress

#Ancient Wisdom#Buddhism#Chinese Philosophy#Contemplative Practice#Cultural Diffusion#Daoyin#Embodied Practice#Energy Cultivation#global health#HRV#Interoception#Jing#meditation#Mind-Body#mindfulness#MMQG#Modern Science#neurobiology#Neuroplasticity#phenomenology#psychophysiology#Qìgōng#Qi#qigong#Raffaello Palandri#Shen#Somatics.#synthesis#Tai Chi#Tai Chi Chuan

1 note

·

View note

Text

The book list copied from feminist-reprise

Radical Lesbian Feminist Theory

A Passion for Friends: Toward a Philosophy of Female Affection, Jan Raymond

Call Me Lesbian: Lesbian Lives, Lesbian Theory, Julia Penelope

The Lesbian Heresy, Sheila Jeffreys

The Lesbian Body, Monique Wittig

Politics of Reality, Marilyn Frye

Willful Virgin: Essays in Feminism 1976-1992, Marilyn Frye

Lesbian Ethics, Sarah Hoagland

Sister/Outsider, Audre Lorde

Radical Feminist Theory – General/Collections

Freedom Fallacy: The Limits of Liberal Feminism, edited by Miranda Kiraly and Meagan Tyler

Radically Speaking: Feminism Reclaimed, Renate Klein and Diane Bell

Love and Politics, Carol Anne Douglas

The Dialectic of Sex–The Case for Feminist Revolution, Shulamith Firestone

Sisterhood is Powerful, Robin Morgan, ed.

Radical Feminism: A Documentary Reader, edited by Barbara A. Crow

Three Guineas, Virginia Woolf

Sexual Politics, Kate Millett

Radical Feminism, Anne Koedt, Ellen Levine, and Anita Rapone, eds.

On Lies, Secrets and Silence, Adrienne Rich

Beyond Power: On Women, Men and Morals, Marilyn French

Feminism Unmodified: Discourses on Life and Law, Catharine MacKinnon

Femininity and Domination: Studies in the Phenomenology of Oppression, Sandra Bartky

Life and Death, Andrea Dworkin

This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, Gloria Anzaldua and Cherrie Moraga, eds.

Wildfire: Igniting the She/Volution, Sonia Johnson

Homegirls: A Black Feminist Anthology, Barbara Smith ed.

Fugitive Information, Kay Leigh Hagan

Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black, bell hooks

Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center, bell hooks

Deals with the Devil and Other Reasons to Riot, Pearl Cleage

Pilgrimages/Peregrinajes, Maria Lugones

In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens, Alice Walker

The Whole Woman, Germaine Greer

Right Wing Women, Andrea Dworkin

Feminist Theory – Specific Areas

Prostitution

Paid For: My Journey Through Prostitution, Rachel Moran

Being and Being Bought: Prostitution, Surrogacy, and the Split Self, Kajsa Ekis Ekman

The Industrial Vagina: The Political Economy of the Global Sex Trade, Sheila Jeffreys

Female Sexual Slavery, Kathleen Barry

Women, Lesbians, and Prostitution: A Workingclass Dyke Speaks Out Against Buying Women for Sex, by Toby Summer, in Lesbian Culture: An Anthology, Julia Penelope and Susan Wolfe, eds.

Ten Reasons for Not Legalizing Prostitution, Jan Raymond

The Legalisation of Prostitution : A failed social experiment, Sheila Jeffreys

Making the Harm Visible: Global Sexual Exploitation of Women and Girls, Donna M. Hughes and Claire Roche, eds.

Prostitution, Trafficking, and Traumatic Stress, Melissa Farley

Not for Sale: Feminists Resisting Prostitution and Pornography, Christine Stark and Rebecca Whisnant, eds.

Pornography

Pornland: How Pornography Has Hijacked Our Sexuality, Gail Dines

Pornified: How Porn is Damaging Our Lives, Our Relationships, and Our Families, Pamela Paul

Pornography: Men Possessing Women, Andrea Dworkin

Pornography: The Production and Consumption of Inequality, Gail Dines

Pornography: Evidence of the Harm, Diana Russell

Pornography and Sexual Violence: Evidence of the Links (transcript of Minneapolis hearings published by Everywoman in the UK)

Rape

Against Our Will, Susan Brownmiller

Rape In Marriage, Diana Russell

Incest

Secret Trauma, Diana Russell

Victimized Daughters: Incest and the Development of the Female Self, Janet Liebman Jacobs

Battering/Domestic Violence

Loving to Survive, Dee Graham

Trauma and Recovery, Judith Herman

Why Does He Do That? Inside the Minds of Angry and Controlling Men, Lundy Bancroft

Sadomasochism/”Sex Wars”

Unleashing Feminism: Critiquing Lesbian Sadomasochism in the Gay Nineties, Irene Reti, ed.

The Sex Wars, Lisa Duggan and Nan D. Hunter, eds.

The Sexual Liberals and the Attack on Feminism, edited by Dorchen Leidholdt and Janice Raymond

Sex, Lies, and Feminism, Charlotte Croson, off our backs, June 2001

How Orgasm Politics Has Hijacked the Women’s Movement, Sheila Jeffreys

A Vision of Lesbian Sexuality, Janice Raymond, in All The Rage: Reasserting Radical Lesbian Feminism, Lynne Harne & Elaine Miller, eds.

Sex and Feminism: Who Is Being Silenced? Adriene Sere in SaidIt, 2001

Consuming Passions: Some Thoughts on History, Sex and Free Enterprise by De Clarke (From Unleashing Feminism).

Separatism/Women-Only Space

“No Dobermans Allowed,” Carolyn Gage, in Lesbian Culture: An Anthology, Julia Penelope and Susan Wolfe, eds.

For Lesbians Only: A Separatist Anthology, Julia Penelope & Sarah Hoagland, eds.

Exploring the Value of Women-Only Space, Kya Ogyn

Medicine

Witches, Midwives and Nurses: A History of Women Healers, Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English

For Her Own Good: 150 Years of the Experts’ Advice to Women, Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English

The Hidden Malpractice: How American Medicine Treats Women as Patients and Professionals, Gena Corea

The Mother Machine: Reproductive Technologies from Artificial Insemination to Artificial Wombs, Gena Corea

Women and Madness, Phyllis Chesler

Women, Health and the Politics of Fat, Amy Winter, in Rain And Thunder, Autumn Equinox 2003, No. 20

Changing Our Minds: Lesbian Feminism and Psychology, Celia Kitzinger and Rachel Perkins

Motherhood

Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution, Adrienne Rich

The Reproduction of Mothering, Nancy Chodorow

Maternal Thinking: Toward a Politics of Peace, Sara Ruddick

Marriage/Heterosexuality

Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence, Adrienne Rich

The Spinster and Her Enemies: Feminism and Sexuality 1880-1930, Sheila Jeffreys

Anticlimax: A Feminist Perspective on the Sexual Revolution, Sheila Jeffreys

Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman, Michele Wallace

The Sexual Contract, Carol Pateman

A Radical Dyke Experiment for the Next Century: 5 Things to Work for Instead of Same-Sex Marriage, Betsy Brown in off our backs, January 2000 V.30; N.1 p. 24

Intercourse, Andrea Dworkin

Transgender/Queer Politics

Gender Hurts, Sheila Jeffreys

Female Erasure, edited by Ruth Barrett

Testosterone Rex: Unmaking the Myths of Our Gendered Minds, Cordelia Fine

Delusions of Gender: How Our Minds, Society, and Neurosexism Create Difference, Cordelina Fine

Sexing the Body: Gender and the Construction of Sexuality, Anne Fausto-Sterling

Myths of Gender, Anne Fausto-Sterling

Unpacking Queer Politics, Sheila Jeffreys

The Transsexual Empire: The Making of the She-Male, Janice Raymond

The Inconvenient Truth of Teena Brandon, Carolyn Gage

Language

Speaking Freely: Unlearning the Lies of the Fathers’ Tongues, Julia Penelope

Websters’ First New Intergalactic Wickedary, Mary Daly

Man Made Language, Dale Spender

Feminist Theology/Spirituality/Religion

Beyond God the Father: Toward a Philosophy of Women’s Liberation, Mary Daly

Gyn/Ecology: The Metaethics of Radical Feminism, Mary Daly

The Gods and Goddesses of Old Europe, Marija Gimbutas

Woman, Church and State, Matilda Joslyn Gage

The Women’s Bible, Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Pure Lust, Mary Daly

Backlash

The War Against Women, Marilyn French

Backlash, Susan Faludi

History/Memoir

Surpassing the Love of Men, Lillian Faderman

Going Too Far: The Personal Chronicles of a Feminist, Robin Morgan

Women of Ideas, and What Men Have Done to Them, Dale Spender

The Creation of Patriarchy, Gerda Lerner

The Creation of Feminist Consciousness, From the Middle Ages to Eighteen-Seventy, Gerda Lerner

Why History Matters, Gerda Lerner

A Vindication of the Rights of Women, Mary Wollstonecraft, ed.

The Elizabeth Cady Stanton-Susan B. Anthony Reader: Correspondence, Writings, Speeches, Ellen Carol Dubois, ed., Gerda Lerner, Elizabeth Cady Stanton

The Suffragette Movement, Sylvia Pankhurst

In Our Time: Memoirs of a Revolution, Susan Brownmiller

Women, Race and Class, Angela Y. Davis

Economy

Counting for Nothing: What Men Value and What Women Are Worth, Marilyn Waring

For-Giving: A Feminist Criticism of Exchange, Genevieve Vaughn

Fat/Body Image/Appearance

Shadow on a Tightrope: Writings by Women on Fat Oppression, Lisa Schoenfielder and Barb Wieser

Beauty and Misogyny: Harmful Cultural Practices in the West, Sheila Jeffreys

Can’t Buy My Love: How Advertising Changes the Way We Think and Feel, Jean Kilbourne

The Beauty Myth, Naomi Wolf

Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body, Susan Bordo

The Invisible Woman: Confronting Weight Prejudice in America, Charisse Goodman

Women En Large: Photographs of Fat Nudes, Laurie Toby Edison and Debbie Notkin

Disability

With the Power of Each Breath: A Disabled Women’s Anthology, Susan E. Browne, Debra Connors, and Nanci Stern

446 notes

·

View notes

Text

[“It may come as no surprise that the legal definition of the worker/surplus binary first emerged after a significant shock to what we would now call public health: a labor shortage in the United Kingdom resulting from the mass casualties of the Black Death.

The first Statute of Laborers, passed in 1349, was issued by Edward III’s Parliament in response to fears of the growing leverage commanded by workers to demand better wages in a more favorable post-plague labor market. After years of plague, in which up to a third of the lower class of Britain died, a crisis of economic and labor power had arisen. In response, Parliament passed laws requiring workers to cede total control of their labor conditions to the ruling class and its state representatives. This novel legal framework compelled all able-bodied people below the age of sixty to work and criminalized all who refused.

The statute explicitly stated that what we would now call a “work requirement” needed to be instituted “because a great part of the … workmen and servants has now died in that pestilence, some, seeing the straights of the masters and the scarcity of the servants, are not willing to serve unless they receive excessive wages, and others, rather than through labour to gain their living, prefer to beg in idleness.” Idleness was made out to be a looming social threat, posing an existential crisis not just to the ruling class but to the national body politic.

The statute narrowly defined those who deserved to be excluded from compulsory work as a specific set of groups: those considered to be legitimately “crippled,” people over the age of sixty, land owners, and business owners. The point was not just to regulate the non-working poor but to establish a categorical distinction between the “idle” or “vagrant” poor and unemployed workers, all of whom were seen as greedily withholding their labor power from the ruling class. The idle poor were categorized as permanently spoiled, biologically irredeemable. It was put to question if they did, or should, even retain membership in the body politic. Some, however—like the unemployed, holding out for their right to better wages—were considered by the state to be recapturable assets who could be reintegrated into the existing social fabric with the same poverty wages as before the plague. For this reason, the statute not only prohibited idleness but intentionally limited the power of employed workers by putting a maximum cap on what a worker could be paid and setting a number of other highly restrictive novel limitations on worker rights.

Under the new law, quitting a job for any reason was illegal. If a worker was fired, the law granted permission for state officials to assign them to new work that they were legally unable to refuse. The stakes for disobeying the work order were raised, and the resulting punishment to the idle poor, those deemed not sufficiently disabled to “deserve” freedom from work, became an incentive to accept exploitative labor conditions.

To enforce these distinctions, workers who refused to bend to the new will of law were characterized as a kind of social plague, weaponizing the memory of death and destruction that had just ripped through the lower classes over the course of the Black Death. Vagrants, cripples, paupers, and beggars were pathologized as morally and biologically spoiled, lacking the will to fulfill their potential as upstanding citizens. Illness, impairment, and disability had already been framed under Christian religious dogma as a personal lack; in many cases even considered to be a kind of phenomenological punishment for sin or bad deeds. The sins of the father, mother, or the self were thought to be marked by divine commandment upon the body. Despite this fatalistic and moralistic framing, there were many formal and informal means of meager almsgiving that supported both the lower classes and those marked as spoiled under Christian dogma. By outlawing idleness and banning the church’s previous policies regulating almsgiving, the new statute prohibited the giving of charity to all but the most verifiably deserving poor. As the statute stated,

Because that many valiant beggars, as long as they may live of begging, do refuse to labour, giving themselves to idleness and vice, and sometimes to theft and other abominations; none, upon the said pain of imprisonment shall … give any thing to such, which may labour … so that thereby they may be compelled to labour for their necessary living.

Vagrancy and poverty became in this way not only morally and spiritually stigmatized as a personal lack or as punishment for sin, but were now framed as a social problem caused by the lack of work, which could only be solved through the re-application of work. Until the idle body returned to work, it was in need of intervention and cure. Idleness became a sickness that must be cured at the source, lest it “go plague” and spread throughout the rest of the population, destroying hope for humanity like some sort of social virus.

The statute was enormously successful in suppressing labor power, and gradually Parliament expanded the state’s oversight of the lower classes. In 1563, the poor were further separated into three distinct legal categories. This addition constituted the development of a continuum of deservingness, a kind of taxonomy of poverty, measuring degrees of social contagion and expanding the understanding of one’s employment status as being an outward reflection of one’s overall health. Each tier came with its own unique stigma and unique relationship to work and the economy.”]

health communism, by beatrice adler-bolton and artie vierkant, 2022

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Philosophy of the Body

The philosophy of the body explores the body as a central element of human existence, focusing on its role in shaping identity, perception, experience, and relationships. This field touches on various areas such as phenomenology, ethics, aesthetics, and politics, addressing how the body is both experienced subjectively and treated within social and cultural contexts.

Key Themes in the Philosophy of the Body:

Embodiment and Subjectivity:

The body is not just an object we possess but an integral part of our being in the world. Maurice Merleau-Ponty, in his phenomenology of the body, argued that we experience the world through our bodies. The body is the medium through which we perceive and engage with our environment, shaping how we exist in the world.

Embodiment is the concept that the body is not separate from the mind or consciousness but that our bodily experiences are essential to our identity. It challenges the traditional Cartesian dualism that separates mind and body, emphasizing the unity of physical and mental experience.

The Body and Identity:

The body is central to personal identity, not just as a biological entity but as a socially and culturally defined construct. Gender, race, disability, and other aspects of identity are often tied to bodily experience and representation.

Feminist philosophers, such as Judith Butler, have examined how bodies are socially constructed and how cultural norms around gender and sexuality shape bodily experiences. Butler’s concept of performativity suggests that gender identity is created through repeated bodily actions rather than being an innate property of the body.

The Lived Body:

In phenomenology, the concept of the lived body refers to the body as it is experienced from the inside, as opposed to the objective body, which is viewed from the outside by others. This distinction, explored by philosophers like Edmund Husserl and Jean-Paul Sartre, focuses on how we inhabit our bodies and how this shapes our experience of the world.

The lived body is not just a passive object; it is active in the way it shapes our perception and interaction with the world. This perspective is particularly important in understanding conditions like pain, illness, and disability, where bodily experiences disrupt everyday functioning and self-understanding.

Body and Power:

Michel Foucault examined how societies regulate and control bodies through various institutions, such as prisons, schools, and hospitals. Foucault’s idea of biopower refers to the ways in which modern states exercise control over the biological aspects of populations, including health, sexuality, and reproduction.

The body is also a site of resistance. Foucault and others have explored how marginalized groups use their bodies in acts of resistance, from hunger strikes to protests, to challenge societal norms and power structures.

The Sexual Body:

The body is a primary site of sexual identity and expression. Philosophers such as Simone de Beauvoir and Luce Irigaray have explored how bodies are sexualized and how gendered experiences shape our understanding of the body.

The philosophy of sexuality explores how bodily desires and relations influence human experience, autonomy, and ethics. It also raises questions about consent, objectification, and the commodification of the body, particularly in discussions about sex work, pornography, and reproductive rights.

The Aesthetic Body:

The body is often seen as an object of beauty and aesthetic appreciation. Aesthetic philosophy explores how bodies are judged based on beauty standards and how those standards are influenced by cultural, historical, and social factors.

Philosophers like Nietzsche and Kant have considered the relationship between bodily form, beauty, and the sublime. Feminist critiques of beauty standards argue that societal expectations about bodies, particularly women’s bodies, lead to objectification and unrealistic ideals that shape how people experience their bodies.

The Body in Medicine and Health:

The philosophy of medicine deals with questions about health, disease, and the treatment of the body. Issues such as the ethics of organ donation, euthanasia, and reproductive technologies all involve philosophical debates about the nature of the body and its moral status.

The body in health and illness is a subject of philosophical inquiry, particularly in the phenomenology of pain and suffering. The experience of illness can change one's relationship with their body, shifting it from a transparent part of existence to an object of focus and concern.

The Body in Sport and Performance:

The role of the body in sport, dance, and other forms of physical performance raises questions about the limits of human ability, the relationship between mind and body, and the ethics of bodily enhancement.

Transhumanist philosophy debates the use of technology to enhance bodily capabilities, asking whether we should augment the body’s natural limits through genetic engineering, prosthetics, and other forms of biotechnology.

The Political Body:

The body is deeply political, often at the center of debates about rights, freedom, and equality. Issues like abortion, euthanasia, and bodily autonomy raise philosophical questions about who has the right to make decisions about the body.

The political body also includes discussions about race and ethnicity, where certain bodies are marginalized or discriminated against due to historical and social power dynamics. Postcolonial theory examines how bodies are racialized and how colonial power shaped the understanding of non-Western bodies.

Body and Technology:

Advances in technology, particularly in areas like cyborgs, prosthetics, and virtual reality, have transformed our understanding of the body. The merging of body and machine leads to philosophical questions about what it means to be human and how technology changes our relationship with our own bodies.

The body’s interaction with digital spaces also raises questions about identity, as virtual avatars and digital representations of the body become common in online interactions. This creates new possibilities for bodily identity, but also new challenges around authenticity and presence.

The philosophy of the body is a vast field that encompasses existential, ethical, political, and aesthetic dimensions. The body is central to our experience of the world, shaping how we perceive, interact, and relate to others. It is both a site of personal identity and social meaning, influencing everything from our everyday interactions to our most profound ethical decisions. The body’s role in shaping human life continues to be a central concern across various philosophical traditions.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#education#chatgpt#ontology#metaphysics#psychology#Embodiment and Phenomenology#Body and Identity#Gender and Sexuality#Power and Biopolitics#Aesthetics of the Body#Body in Medicine and Health#Body and Technology

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Philosophical question: What makes art "good"?

I've been sitting on this ask for a while. On the one hand, it'd be way easier to just say "thousands of pages have been written on this topic with no agreeable consensus yet, so what does it matter what I think?" On the other hand, this exact question came up in one of my discords recently, and I remembered this is still a real question for people who don't spend their time combing through those thousands of pages. I'll try to give some personal thoughts. This is going to be a long one, so apologies in advance.

First, I have to assume that anyone reading this believes there is a real distinction to be made between that which is art and that which is not. Art is the resultant of intention for the purpose of aesthetic engagement. A chair might be beautifully crafted and have significant aesthetic qualities, but its true function is as a piece of furniture. To that end, it might be artisanal, but it is not art, strictly speaking. Those who say "art is whatever you think is art" (or similar derivatives) do not actually believe it, because their entire goal is to appropriate the label "art" for whatever product or commodity they personally value, which would be a meaningless goal if they did not already recognize the label "art" as a non-subjective signifier. For the purpose of this post I'll be containing my thoughts to visual arts specifically (music, literature, drama, and poetry are surely arts, but they will make things slightly more difficult).

In philosophy, the discipline of phenomenology seeks to explore experience as such. One might argue that Kant acted as a precursor to phenomenology with his distinction between phenomenon and noumenon, the former being that which is accessible to us through our senses. Since art is an aesthetic endeavor, this makes modern philosophical questions about art inextricable from questions about phenomenology, because art is something we must experience with our senses. We see paintings, we hear music, etc, but what are sights and sounds really, and how do we explain emotional responses to empirical stimuli?

One concept in phenomenology I find particularly useful in the domain of art is the concept of intentionality. In short, all of our thoughts are about something. We do not have free-form, disconnected thoughts, but rather thoughts that are directed towards particular concepts, objects, or feelings. We have thoughts with intention. This might seem obvious at first, but it has grave implications for our connectedness to the real world. If all of our thoughts are about things, then it is things (be they concrete or abstract) that anchor our minds to the world. Indeed, this is the crux of the Kantian paradigm (though he predated the modern terminology).

What does this mean for art, and how does it affect what one might consider "good" vs "bad" art? Here we get to the messiness of the objects of our thought. Is it possible for one to have their thoughts directed at the wrong thing?

I'm going to take a step to the side here and illustrate my perspective from a parallel street: the distinction between the erotic and the pornographic. In the modern uses of the word, the two are practically synonyms, but this is the result of a modern world that values pornography over all else, perverting the natural domain of the erotic in the process. So what is the difference? All human beings experience sexual desire, but we understand that sexual desire and lust are not identical.

In true sexual desire, we feel the erotic impulse not merely for the body of our beloved, but for our beloved embodied. We see in our beloved the self-experience of their entire person, a self-experience we recognize within ourselves, and we seek to bridge the gap between self and non-self, us and them. Christendom recognized this truth in its pronouncements that in the sacrament of marriage, man and woman become as one flesh. In a more romantic idiom, we recognize this impulse when we get lost in the eyes of our beloved. It is not the literal pupils and irises we see, but the person behind those eyes. In the sexual act, we consummate our desire as erotic love, the intention of which is directed at our beloved as a subject. Sexual desire, at its heart, is a search for knowledge of the Other: it is an outward direction passion of epistemology.

Lust, by contrast, is entirely directed inwards. We are only too familiar with lust as an appetite. Lust makes no regard for the personhood of its object, because the object of lust can be replaced at a whim. Imagine if someone suggested that you replace your true love with a nicer, more beautiful man/woman: the idea is so absurd it's insulting. But the accessibility and variety of modern pornography perfectly illustrates the non-specificity of lust. It doesn't matter what an object of lust is, because it is in the satisfaction of the self that the appetite of lust is sated. Lust denies the personhood of its object, which is why lust in its most extreme and degenerate forms (rape and pedophilia) can satisfy itself with any number of victims, each just as good as another. (As an aside, this is why pornography is so perverse. It displaces and usurps healthy desires with false substitutes. Note that this description also applies to much non-sexual products of the modern world.)

I'm sure you can see where I'm going here. The erotic attempts to use art to explore the dimension of sexual desire, a natural and fundamental part of the human condition. The pornographic serves to satiate the appetite of lust.

See here the Titian "Venus," an exploration of erotic beauty in the divine. Here the body is at perfectly at rest. The Venus could be clothed from head to toe, and her natural posture need not change in the slightest. She is in complete awareness of her form, and she gazes at the viewer with the relaxed confidence of a transcendent beauty. The viewer is drawn automatically to her face, which veils her nude body from perversity. You cannot objectify this woman, her flesh is off-limits to base appetites. Instead of consuming her, we adore and appreciate her, admiring from a distance the perfection of her features and the sublimity of her Self. We see in her a woman embodied, flesh and spirit entwined.

The male gaze meets the erotic (like the Venus) and feels a desire for more than mere flesh. She is pure subjectivity, and a function of sexual desire is to know that subjectivity as one's own. This is not a uni-directional force, however, and in the erotic moment that desire for knowledge compels us to make ourselves vulnerable for our beloved, that they might do the same for us. The Venus's eyes are both sword and shield, her face both an invitation for vulnerability and a bulwark against obscenity.

It's not exclusively in the beauty of the divine that we encounter erotic passion in art, however, and certainly human beings are not gods. See here a more terrestrial exploration of the erotic in Manet's "Olympia."

Notice first the similarities to the Titian: a nude figure, a relaxed posture, a self-awareness in expression. But immediately differences are apparent. This is no goddess, but a woman of flesh and blood. Hers are not the spotless hands of the divine, but the earthly hands of caresses, of money-handling, perhaps even of violence. Her features are hardened, but they are true. And like the Venus, her face holds vigil above her form. We see in her expression an entire person, a woman with a history, will, and total self-knowledge. She too is off-limits, but for more imminent reasons than the Venus, for this is a more imminent beauty.

In the Venus and the Olympia we see the body unashamed. They are bodies in sublime reclination, perfectly at one with themselves in their nakedness. Theirs is not a nudity of advertising or intentional display, but instead of total leisure. The veil between the viewer and these women holds fast, and we see in them a representation of the female form in all its splendor. These are not "real" women (though their models doubtlessly were), and so for the viewer, they are the subjects of imagination.

By way of contrast, let us move now to a work of false eroticism, Boucher's "Blonde Odalisque."

Striking differences are at play here. Most apparent is the subject's posture, an unnatural and inexplicable pose that she would never hold if she was fully clothed. This is not the body at rest, it is the body on display. The face is another red flag, as it has no feature to play in the body's composition, and we have no reason to be drawn towards it. Whether she is intentionally avoiding our gaze or is simply unaware of it, her subjectivity is compromised, and we are free to engage in more lecherous mental activity. This is not the body unashamed, like the Venus or Olympia. Instead, it is the body shameless. Her nudity, while beautiful, is dangerous and borders on advertisement. There is no history in this woman that concerns us beyond her bare flesh, and therefore she is not a fully intact agent to us. The erotic here is impossible, and we have brushed against the boundary of the pornographic.

What conclusions can we draw? The Titian and the Manet are works of art that pull our thoughts into them, realms of fantasy where the imagination must work, wrestle, and play with perspectives of subjectivity and the erotic. The Boucher also pulls at our thoughts, but not with the same end, instead providing an immediate satisfaction for fantasy in the form of a readily present object. There's no room for imagination here beyond inward-focused lechery.

Here we encounter another difficulty in art, the conflation of technical execution to artistic expression. One cannot deny Boucher's remarkable skill as a painter. But that skill does not automatically endow expressive merit to a work of art. Compare especially the Titian to the Boucher - the compositions have similarities in form but not in content, because there is more to a work of art than the literal pigments on the canvas. Those who cannot penetrate beyond the surface-level sense impressions of a work will find it difficult to delineate between genuine artistic expression and the evocation of mere sentimentality. Art must take itself to be fundamentally serious, and in that vein it cannot properly provide gratification for fantasy, for such satisfaction would be illusory. Where gratification comes easy, artistic expression recedes.

And now we return to the question at hand with a new perspective on what makes art "good." "Good" art is art which exists for its own sake, while "bad" art (and I'm using the word "bad" here very loosely, for much "bad" art is still skillfully executed) is art which exists for the sake of the emotions and feelings it satisfies in those who engage with it. In the phenomenological phrasing, "good" art pulls the intentionality of thought outwards, while "bad" art confines it inwards (metaphorically speaking). Indeed, it is the very notion of "inward-focused intentionality" that seems to be the defining feature of what the art-world calls kitsch.

We all know kitsch when we see it. The art on greeting cards, or in hotel lobbies, or in Precious Moments figurines. These are things that exist for the sole purpose of arousing an emotional response, and it is in that response that we find satisfaction. The automatic "awww" that we coo out when we open a birthday card with a cheesy poem inside is categorically different from the "awww" we whisper when we hold a sleeping infant. In this sense, kitsch is emotional pornography, in that its function is to both induce and satisfy an emotional craving without pulling one's thoughts towards anything except their feelings.

Much of modern art is kitsch. Some "artists" like Koons go so far as to produce works that are so blatantly obviously kitsch that it preempts the criticism, as if to say "I know this is looks kitsch, so it transcends the label into new territory, and you can't call it kitsch anymore." Such works are stupendously popular among art critics, because in a world where beauty is considered dangerous and hierarchical, the current vogue is to be as offensive to taste as possible. Other modern works are elaborate exercises in mental masturbation, a kind of "Emperor's New Clothes" litmus test for the anointed of the modern art-world. In these overly intellectualized forms of kitsch, the "merit" is found in one's own capacity to recognize and appreciate said "merit," and those who can't probably aren't sophisticated enough to understand.

But this presents another danger in the opposite direction, the glorification of tradslop. In an effort to signal as hard as possible an opposition to the trends of modernity, tradposters and right-wingers alike have fallen into the habit of idolizing prettier forms of kitsch.

Thomas Kinkade paintings all have exactly one function, to satisfy one's emotional cravings for idyllic coziness or nostalgia. On the surface it appears more "traditional" than Koons (or at least less "modern"), and the accessible prettiness makes it attractive as a counter-signal to the abstract ugliness of hypermodernity. Like the Boucher, the Kinkade has genuine merit in form and composition, use of color, perspective, and lighting (a trademark specialty of Kinkade). But beneath the surface, there is no genuine content in a Kinkade landscape, no representation for our imaginations to occupy, because it is purely for the sake of the emotional response of the viewer that the landscape exists. It is a prop that is satisfying to look at because that is its function.

By way of comparison, let's look at Wyeth's "Christina's World," a mid-20th century painting that, ironically, was considered too kitsch on its debut because it wasn't abstract enough. The Wyeth, like the Kinkade, induces a kind of nostalgia on first impression. But unlike the Kinkade, the nostalgia here is for a world rooted in reality. Our gaze moves from Christina to the homestead and back, scanning everything from her clothes to the tracks in the field for clues of the human life depicted. We might feel grief for the loss of a world long-past, recognition in the home depicted and the familiarity of its contents, or empathy in Christina's course towards the property. In all of this, our imaginations dance within Wyeth's representation, a somber and sublime depiction of Americana, but separate from us, enframed as an end in itself.

My suspicion is that in the modern world of commercial product, we are so inundated with a constant stream of slop that we are primed to overexcitedly pedestalize even mediocre content to heights it doesn't deserve. Film and videogame soundtracks are "just as good" as the symphonies of Beethoven, because they both use orchestras, right? The pop music of Phil Spector was pure genius compared to his contemporaries (and successors), but does that make it more artistically sound than the Wagnerian element he utilizes? Game of Thrones might not be Shakespeare, but it's got to be better than Harry Potter, isn't that good enough? Why not enjoy Kinkade when everything else is either perverse or Corporate Memphis blob art?

The "product vs art" discussion is sticky, because in a world dominated by the democratic atmosphere, it's forbidden to suggest that one's taste in anything, from food to films, might be inferior to another's. "Just let people enjoy things!" It is sobering to remember that the most effective products for mass consumption are those manufactured to satisfy the lowest common denominator, and what is more satisfying than the instant gratification of fantasy? But if one cares about art as a feature of humanity's impulse to create, then one must recognize that, like human beings themselves, not all art (and certainly not all product) is created equal. If it were, criticism would be impossible.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Akechi's taste in Literature

I've taken an interest in the books Akechi reads. Obviously from the first time you talk with him, you can already tell what he tends to: psychology, philosophy, and mythos. Also, I read at least a little bit from every text. One of my professors out there is proud of me. I hope. So: let's talk about it!

Ok, but why care? Quick Introduction

No particular reason. I simply want to tinker with his brain. I think it could give us insight on the character! And there's an easy way to dismiss this conversation: Akechi uses books as a way to appear intelligent. I don't think that's wrong per se, but he does express an interest in psychology and philosophy in his third semester Jazz Jin discussions. His thieves den conversations also point to interests in mythos. Use this as a "Annoying Person Bookshelf" if you'd like, I certainly will.

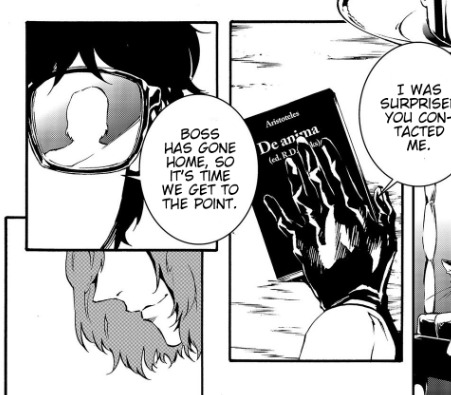

Aristole's De Anima (Mementos Mission - Chapter 3)

De Anima, or "On the Soul" [Leob Classical Library], is an examination of the soul and how it functions within the body. It's pretty dense but easily accessible. On page 15,

"There are times when men show all the symptoms of fear without any cause of fear being present. If this is the case, then clearly the affections of the soul are formulae expressed in matter."

Now, I'm not going to read every book, that would be a huge investment. And unfortunately I am still a university student, so I'll stick to the introduction/first chapters or so. But anyways, to the point of the quote, De Anima tends to get metaphysical. Theory time: Akechi has morbid fascinations with the soul. Not only because he well, kills people, but also messes with the restraints on their heart. I choose this quote because it's a good summary of the kind of body horror someone messing with you in the metaverse is like. It's fear and anger unchained, but it manifests in reality through subway accidents... for example.

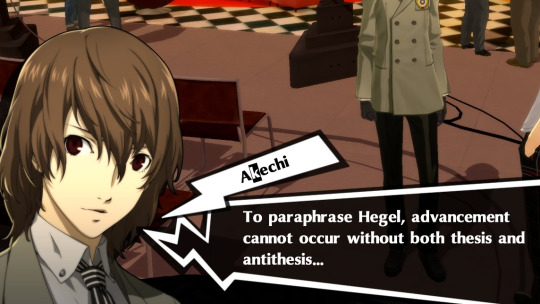

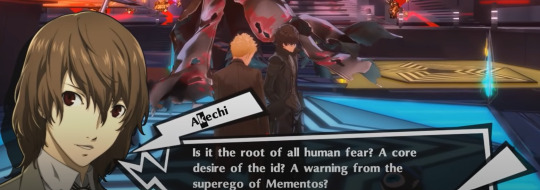

Hegel's Dialectics (did Akechi misquote Hegel?) - Rank 1

Look, almost all of these texts are slogs to get through, so I wouldn't blame Akechi for not catching this. Or not reading the 2017 in-universe equivalent of cliffnotes. Note: Dialectics refers to the structure/strategy that Hegel uses, not a text itself. Looking at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy we see that Hegel never makes mention of the thesis, antithesis, and synthesis idea. Rather, thesis-antithesis-synthesis is a pattern in his arguments. These are also projected by people reading his text, so we can't fully be sure he's using this to formulate most of his arguments. So not only has Akechi forgotten synthesis, the "unification", but also the fact that Hegel doesn't talk about this. Did he read Hegel? Probably. Did he retain the information? Questionable. Do I blame the writers for making the mistake? mmmm. Maybe. If you're asking me to guess which book he read, I would estimate it was The Phenomenology of Spirit [Google Books]. And yes, I'm going to say it was just because of this quote on page 9 that just, screams Black Mask:

"The force of the mind is only as great as expression; its depth only as, as deep as its power to expand and lose itself when spending and giving out its substance."

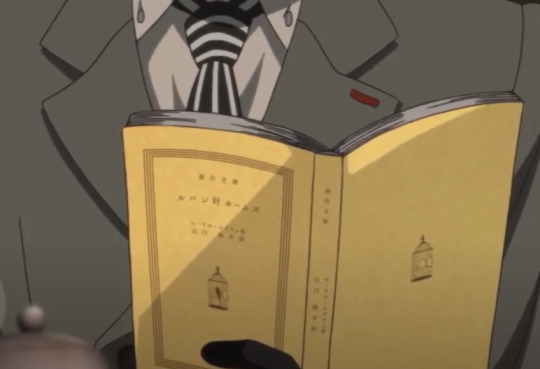

Maurice Leblanc's Arsène Lupin vs Sherlock Holmes (Herlock Sholmes) (P5A)

This book I read because my curiosity definitely got the better of me. Since I've gotten into Persona 5 again, I've been DYING to read this one, but never got around to it. I think this one is also interesting to look at based on how it was represented in the anime, a crow escaping a bird cage. I can say that this doesn't happen in the book, but this is why I think Akechi is self inserting on Holmes/Sholmes here. Holmes is much freer as a person in this text than Akechi, but also in a deep rivalry with Lupin. Their banter is also pretty reminiscent of what they [Joker and Akechi] have, but... with older language. Longer quote, so here's an image in its place:

Edit/Correction: Edogawa Ranpo's Kogoro Akechi Series!

As pointed out by a couple people, we can't leave out this series. (credits to @heavy-metal-papillon) I don't know why my mind blanked and left this out. Because when I was doing research for this post someone had mentioned it. Just by name, it should be obvious why this is here! Here is a part of the preface that explains Kogoro Akechi, Arsene Lupin, and their presence in Edogawa's novels (written by Ho-Ling Wong):

Literature he makes references but doesn't mention (note: headcanon/my opinion)

John Stuart Mill's On Utilitarianism

Because Akechi knows how to flirt, he recommends philosophy to Joker. [Early Modern Texts] In my eyes he definitely doesn't agree with this philosophy (in fact some quotes are definitely more aligned with Maruki's philosophy). Page 8:

"That’s because the utilitarian standard is not •the agent’s own greatest happiness but •the greatest amount of happiness altogether; and even if it can be doubted whether a noble character is always happier because of its nobleness, such a character certainly makes other people happier, and the world in general gains immensely from its existence."

Yes, Akechi reads Freud. Freud's essays: Beyond the Pleasure Principle & The Ego Principle

In an offhanded comment about Personas in the Thieves Den to Ryuji, Akechi says:

I love you Akechi. I will not read Freud for you. My love has limits.

Carl Jung's Two Essays on Analytical Psychology

Okay I'm NOT reading this (a lie, i did. [Internet Archive]) but this was the foundational text on the Jungian Archetype of the Persona as well as addressing concepts such as "the will to power." Going to leave this quote from page 78 for you to munch on:

"Logically, the opposite of love is hate, and of Eros, Phobos (fear); but psychologically it is the will to power. Where love reigns, there is no will to power; and where the will to power is paramount, love is lacking. The one is but the shadow of the other..."

There's a couple things here that point to Akechi reading this, but ultimately I just headcanon that he wants to reason through why Personas exist.

Generally reads about the casts Personas!

Similarly to how Joker can read about the other PTs Personas, Akechi does as well. Well, if his morbid discussion about Captain Kidd in the Thieves Den is an indicator. Does this mean Akechi is familiar with the Carmen stage opera? I think so. Besides, it's also the smartest move. Akechi (head)canonically reads lovecraft.

Conclusion

Akechi really enjoys psychology and philosophy, and while some of it seems like he's doing it for attention/to appear smarter, he DOES continue to show interest in third-semester/thieves den. I still can't forgive him for reading Freud.

The List (of ones directly mentioned here)

De Anima, Aristotle

The Phenomenology of Spirit, Hegel

Arsène Lupin vs Sherlock Holmes, Leblanc

On Utilitarianism, John Stuart Mill

Beyond the Pleasure Principle & The Ego Principle, Freud

Two Essays, Carl Jung

The Fiend with Twenty Faces, Edogawa Ranpo

Other notes and headcanons I can't justify giving sections to:

he probably read that fuckass billiards book

definitely stuff on justice. i was just lazy. Some of these texts do cover these ideas, but definitely not all of them

he likes detective novels. he's probably read a fair share of sherlock holmes.

he probably reads adjacent literature to some of the philosophers mentioned (for example: Nietzsche to Jung, Plato to Aristotle)

#goro akechi#p5 meta#p5r#p5#akechi goro#akechi#thinking emoji#making goro akechi's philosophies everyone's problem

155 notes

·

View notes