#Stuart Devlin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Lester Bookbinder - Jeweled Egg by Stuart Devlin (Vogue UK 1973)

#lester bookbinder#stuart devlin#vogue#photography#fashion photography#vintage fashion#vintage style#vintage#retro#aesthetic#beauty#seventies#70s#70s fashion#70s style#1970s#1970s fashion#editorial#vogue uk#jewelry

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ulster Museum, Belfast (2023)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ulster Museum, Belfast (2023)

0 notes

Text

..who do i write for ?

✩ everyone i write for might not be in my masterlist yet because i haven’t published anything about them — but that doesn’t mean i won’t

✩ i generally only write for female readers, so if you want anything else specify so in your request

✩ as long as my requests are open any one of these characters are available to send in!

˗ˏˋʚ SKINS UK ɞˎˊ˗

gen two —

cook, freddie, jj, effy, emily, naomi, katie

gen three —

rich, alo, nick, mini, grace (but basically anyone because it’s my favorite gen)

˗ˏˋʚ THE BIG BANG THEORY ɞˎˊ˗

general tbbt —

sheldon, raj, howard, leonard, bernadette, amy, penny, stuart

young sheldon —

romantic; georgie, mary, pastor rob, connie

platonic; missy, sheldon

˗ˏˋʚ MISCELLANEOUS ɞˎˊ˗

male —

austin!elvis, benedict bridgerton, steve harrington, eddie munson, rory!euro, carl grimes, carl gallagher, lip gallagher, phil dunphy, luke dunphy, leo!jim carroll, cillian!oppenheimer, harry potter, ron weasley, mike wheeler, neteyam sully, jj maybank, james maguire

female —

daphne bridgerton, eloise bridgerton, violet bridgerton, nancy wheeler, robin buckley, fiona gallagher, haley dunphy, clare dunphy, gloria pritchett, blair waldorf, ginny weasley, hermione granger, fiona goode, zoe benson, madison montgomery, misty day, beth harmon, michelle mallon, orla mccool, clare devlin, erin quinn

#qtkat#x reader#x reader masterlist#bridgerton x reader#stranger things x reader#skins uk x reader#avatar x reader#gossip girl x reader#american horror story x reader#elvis presley x reader#robert oppenheimer x reader#jim carroll x reader#modern family x reader#harry potter x reader#shameless x reader#outer banks x reader#the queen’s gambit x reader#derry girls x reader

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dark Shadows Ship Tournament: Round One

Collinsport

Barnabas Collins/Julia Hoffman VS. Maggie Evans/Joe Haskell

Aristede/Count Petofi VS. Quentin Collins/Aristede

Jason McGuire/Elizabeth Collins Stoddard VS. Bill Malloy/Elizabeth Collins Stoddard

Jeff Clark/A bullet VS. T. Eliot Stokes/Elizabeth Collins Stoddard

Roger Collins/Carolyn Stoddard VS. Carolyn Stoddard/Chris Jennings

Natalie du Prés/Abigail Collins VS. Julia Hoffman PT/Angelique Collins PT

Quentin Collins/Charity!Pansy Faye VS. Carl Collins/Pansy Faye

Carolyn Stoddard/Burke Devlin VS. Burke Devlin/Elizabeth Collins Stoddard

Bangor

Julia Hoffman/Angelique Bouchard (main timeband) VS. Angelique Bouchard/Laura Collins

Nicholas Blair/Maggie Evans VS. Edward Collins/Kitty Soames

Nathan Forbes/Reverend Trask VS. Willie Loomis/Jason McGuire

Willie Loomis/Maggie Evans VS. Joshua Collins/Naomi Collins

Edward Collins/Kitty Soames/Gerald Soames VS. Roger Collins/Victoria Winters/Burke Devlin

Nathan Forbes/Suki Forbes VS. Roger Collins/Laura Collins

Victoria Winters/Maggie Evans VS. Victoria Winters/Josette Collins

Roger Davis/The eternal fires of hell VS. Quentin Collins/Barnabas Collins

Augusta

Natalie du Prés/Naomi Collins VS. Jenny Collins/Beth Chavez

Julia Hoffman/Quentin Collins VS. Quentin Collins/Maggie Evans (main timeband)

Bruno/Jeb Hawkes VS. Roger Collins/Burke Devlin

Carolyn Stoddard/Tony Peterson VS. Carolyn Stoddard/Jeb Hawkes

Burke Devlin/Victoria Winters VS. Elizabeth Collins Stoddard/Quentin Collins

Carolyn Stoddard/Victoria Winters VS. Josette du Prés/Angelique Bouchard

Edward Collins/Victoria Winters VS. Chris Jennings/Sabrina Stuart

Barnabas Collins/Angelique Bouchard VS. Julia Hoffman/Medical malpractice lawsuit

Rockport

Nicholas Blair/Reverend Trask VS. Roger Collins/Nicholas Blair

Carolyn Stoddard/Buzz Hackett VS. Elizabeth Collins Stoddard/Barnabas Collins

Victoria Winters/Elizabeth Collins Stoddard VS. Carolyn Stoddard/Maggie Evans

Roger Collins/Laura Murdoch/Burke Devlin VS. Carolyn Stoddard/Joe Haskell

Julia Hoffman/Elizabeth Collins Stoddard VS. Judith Collins/Minerva Trask

Quentin Collins/Evan Hanley VS. Gerard Stiles/Quentin Collins

Rachel Drummond/Tim Shaw VS. Roger Collins/Victoria Winters

Quentin Collins/Amanda Harris VS. Jeremiah Collins/Victoria Winters

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Goes Around

Set after part 6 of Conviction: Judgement Day (Series 25) of The Bill. I always sort of felt that Smithy would be more bothered about what he'd done to Devlin but the reboot/quick reshuffle and promotion had to take focus and they couldn't dwell on it too. Here, Smithy and Gina meet up and talk through what happened.

Characters: Smithy and Gina [with a side mention of a certain Jonathan Fox. Because he and Gina definitely reunited now she wasn't an officer. They did. Honest! Ahem.]

What Goes Around

"How did you do it?"

Gina raised her gaze from where she had been studying the label of the expensive bottle of scotch she was about to open. "How did I do it?" she repeated in a thoughtful tone. "How did I do it?" She fixed Smithy with an unwavering stare. "No. Even I haven't mastered the ability to read people's minds yet. How did I do what?"

"Be an Inspector." Smithy took the bottle from Gina's hand and unceremoniously pulled both the seal and cork stopper from it. "You did it for 15 years after all." He shrugged, pouring them both a large measure before he sank a good third of his in one go with barely a wince.

Gina's expression changed from vaguely amused to concerned, knowing whatever it was bothering her friend – it wasn't good. They'd been here many times over the years, both good and bad for each, but this was the first time since her departure from the station 9 months previously that Smithy had been quite so sullen for so long. Usually, he'd moan about his fellow Sergeant Callum Stone and pout for a few minutes before the drink would do its job and the topic change to let them catch up on how each other had been. Often Smithy would tease Gina for not yet starting her walk of the length of Great Britain despite her repeated claims she was going to start it 'soon'.

"Dale-?"

"Meadows' offered me the job." He said, swirling the amber liquid around his glass.

"Jack did?" Gina blinked, "But what about Rachel? And Heaton? Has something happened? Are they alright?"

"Heaton's been headhunted to set up a specialist human trafficking unit. Took Rachel, Kezia and Stuart Turner with him. They all left the same day."

"Bet he's popular," Gina smirked into her glass before taking a sip. "So Jack-?"

"He's the new Super. Heaton put a word in for him." Smithy explained. "He's offered me the Inspector position."

"I'd say congratulations but you don't exactly look as though you're jumping for joy, darlin'." Smithy's hunched body language told her he hadn't yet drunk nearly enough scotch for her to get him to open up. "Jack Meadows is Superintendent again? Only took him 17 years to get back to where he was. Typically it's all of 3 years before he hits retirement." She said, changing tact. "Did you take him up on his offer?" she asked.

Smithy nodded and topped up the glasses. The alcohol, the quiet warmth of Gina's house and the comfort of his closest friend being present after everything that had happened was starting its usual magic. He'd gone to Gina because he knew he could trust her no matter what he'd done. Telling her however was a whole other matter.

He began asking if she'd heard of Matthew Devlin or his son Jason. When she hadn't, he explained that they'd only moved down to London from 'Up North' a couple of years ago and until recently neither been in trouble with the police. "The son, Jason, he's a real psychopath. Went from laughing to kicking a man unconscious in minutes simply because his girlfriend hugged the bloke and kissed him on the cheek when he'd told her he was about to become a father." Smithy took another sip before continuing. "They had houses that were essentially slums and illegal HMOs. They were crammed full of mostly illegal immigrants." He sighed, his mood dipping even further at the memory. "The state of those houses, you should have seen them. There were like 8 or 10 people living, eating, sleeping in one room, repeated in every room of the house."

Gina sighed and gently rubbed his back for comfort, letting him get the emotions he'd bottled up out without her interrupting him and taking him off track. She knew he didn't want sympathy – he wanted to be heard and to tell her something that was obviously troubling him.

Smithy paused only to take another gulp from his glass. "The smell was something else, the fire escapes boarded up with stuff in the way and the fire alarms themselves disabled. The electrics were bare wires – if they worked full stop! There were so many kids in there, you couldn't move for fear of standing on someone. Course they were charging impossible rents for every person." he scoffed. "Claimed they knew nothing about it, that the 'legal' tenants must have "invited their families. The Devlin's got all of a smack on the wrist and a fine for breaching housing violations whilst the tenants got visits from immigration and threats of being sent straight back to whatever horrors they escaped from."

He went quiet for a good couple of minutes, staring miserably into his glass, his knuckles white from the tightness of his grip. Gina stayed quiet, knowing he needed to work through his anger before it came too much for him – little knowing that that was exactly what had already happened. "Turns out they were trafficking them over too. Packing them into crates and loading the lorries in such ways that it was dangerous for customs to investigate further. It's a wonder they even got to Sun Hill from Afghanistan in the first place without anything happening to the people in the back. One of the lorries stopped suddenly where me and Ben were patrolling. The driver took one look at the uniforms and legged it." He finally lifted his gaze, Gina alarmed to see his eyes were red and watering. "The noise, Gina...” He swallowed shakily, it obvious that it had been haunting him.

Gina sighed and moved her hand so her arm was more around him and gave him a gentle squeeze. "I'm sure you did everything that you could. Knowing you, you went above and beyond as always."

Smithy took a deep breath in and sniffed back tears before continuing. "Jala, she's only just 11. She had to watch her father die in front of her whilst she was trapped. She was right next to another man who didn't make it. I had to tell her that her father had died. She's now an orphan. The only family she's got left here is her aunt. I could only get her out, I couldn't save him. He was-"

"It's OK." Gina soothed and slid her other arm around Smithy, letting her head rest against his in comfort as he fought to regain his composure. "You did your best," She soothed. "No one could have asked any more of you."

"Couldn't they?" Gina felt Smithy's shoulders rise under her arm in defense, the action telling her he hadn't yet told her everything that was bothering him.

"You're one of the best coppers I know." She said softly, still holding him so he didn't feel any pressure from eye contact and try to repress everything again without getting it off his chest. "Stupidly brave. Loyal to a fault. Calm under serious levels of pressure that other-" She trailed off at hearing a loud snort of derision come from Smithy and moved her hand from his shoulder to his chin. "What did you do?" She asked, lifting his chin though his gaze remained on the floor, unable to meet hers. Gina sighed, realising that he wasn't upset just at the situation, he was deeply ashamed of something.

"Jason Devlin." He said very quietly, his voice was almost a growl. "He had stolen jewellery in his boot that his associate had removed from those they trafficked over just 'cos they could. He caused a riot on the White Gate estate by forcibly evicting illegal immigrants as part of some stupid big show that he was 'playing by the rules in front of the police." He scoffed. "The residents tooled up and went after him and his goons. We had to remove him from the estate to calm the riot down and try and regain control. Stevie took him to his car after they mobbed the panda they were in to lynch him. She saw the bag and tried to look at it... he kicked her until she was unconscious."

"Oh, Smithy." Gina sighed, closing her eyes briefly, not needing him to spell out what he'd done. "You found her? Is she alright?"

Smithy nodded, turning his head from Gina's hand and sinking the remainder in his glass before speaking. "It was like an out-of-body experience. I just... lost it. I saw her on the ground out cold and went for him before I could do anything else." He swallowed hard, a tear tracing its way down his cheek. "Stone found me. He er, he... checked on Devlin and I er...." he downed another large gulp of his drink. "I checked Stevie and he... he called for ambulances and then the inspector came and Callum took over. Said we found them both and did first aid. He covered up for me, let the bosses think it was a disgruntled tenant that attacked him." He licked his dry lips. "They still do. He's been through court. I perjured myself. I could feel him staring at me from across the courtroom. Knowing every word was a lie."

Gina shook her head, "Knowing that he was responsible for at least two people's deaths just that month alone. Who knows if there have been any more they've 'disposed of' whilst they'd been doing it. Knowing they are ripping off some of the most vulnerable people and their families several times over for a so-called better life only to keep bleeding them dry when they got them here as a captive market." Unlike Smithy's, Gina's tone was calm and measured. "To subject them to God knows what because they have no one else they can tell as they fear being sent back by the authorities or their families being harmed if they did speak out. They have nothing, they're abused, vulnerable and stuck in a circle of giving every last penny they do receive or earn to The Devlin's and his ilk for this 'better life' that just doesn't happen."

She turned his head again. This time Smithy raised his gaze slightly but wouldn't look at her still, unable to meet her gaze for fear of seeing her be disappointed in him. "Whilst I don't condone what you did, I'm not going to punish you for it like you seem to want me to. Smithy, you're not just Sergeant Smith, a robotic android like police officer. You're human. You have emotions and feelings just like everyone else – even me." She paused, Smithy giving her a sad smile in response to her small joke. "Everyone has a breaking point and let's face it, you'd been through an entire roller coaster of emotions in a few short weeks caused by the actions of two toerags. Devlin's not some innocent mixed up in something out of his depth. He actively set out to break the law, to harm and hoodwink some of the most vulnerable people in the world. I'm not going to lose any sleep over him getting a taste of his own medicine and neither should you."

"I broke the law, Gina!" Smithy swallowed, "I assaulted him! I covered it up!"

"You did." she nodded. "But what part of you beating yourself up forever will make that have not happened? What part of you handing yourself in, losing your job, causing a mistrial, having Devlin freed and you potentially inside serves the Jala's of the world? Her, her aunt, her father... the real victims? You're a million times more useful to them and every other victim of crime that you come across where you are now, doing the job you've dedicated yourself to. Besides, if he got a chance he'd have done the same – if not worse – to you. This changes nothing."

Smithy swallowed and finally raised his gaze to meet Gina's. "So why do I feel like I'm a fraud? Why doesn't it feel like I deserve a promotion? Deserve to still have my job even?"

"Because you're a good man as well as a good officer," Gina said gently. "You know you did wrong and you know that the consequence of that is punishment. But Smithy, you've already punished yourself for what happened. Devlin is where he needs to be. He'd still be locked up for what he did either way whether this had happened or not. You just need to come to terms and accept that it did happen and draw a line under it. It's over. You'll be paying your penance through just doing your job and looking after everyone else but yourself." she said with a wry smile – one which Smithy mirrored in response. "Anyway; now you're on Inspector's wages, you can finally start bringing the scotch if you're going to make me listen to you being an old woman each time."

"Charming!" Smithy poured them both another drink and clinked his glass against Gina's in both cheers and thanks. "I'll remember that next time you're moaning about something Fantastic Mr Fox did or didn't do because you didn't tell him what you really meant." He smirked slightly before looking almost 'innocent'. "How is Jonathan by the way?

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

other medias muses

Alexander Clearmond Diaz-red, white, & royal

Clare Devlin-Derry Girls

Gregory Eddie-Abbott Elementary

Jim Halpert-The Office

Lacey Porter-Twisted

Janine Teagues

Henry Stuart Fox -red, white, & royal

Glimmer-She Ra

#indie rp#rwrb rp#red white and royal blue rp#abbott elementary rp#the office rp#she-ra rp#&&starter calls#&&starter calls:general

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

like/comment (if you are a multi) for a one-line starter

other medias muses

Alexander Clearmond Diaz-red, white, & royal

Clare Devlin-Derry Girls

Gregory Eddie-Abbott Elementary

Jim Halpert-The Office

Lacey Porter-Twisted

Janine Teagues

Henry Stuart Fox -red, white, & royal

Glimmer-She Ra

#&&starter calls:general#&&starter call:other media#thought we built a dynasty that heaven couldn't queue up

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Devlin is a sort of kenmarite quasi-conservative along the lines of edmund burke. mary's views are very similar but she's less obsessed with, how do I say this, dublin politics as an institution. to speak more clearly of donal specifically I think that he's a general opposition to the government which is not far from english radicalism as personified by the london corresponding society or maybe henry hunt; his views are very influenced by his time in the army and his proximity to the napoleonic wars on the continent. eoin... well he doesn't actually really know very much about the stuarts tbqh but he doesn't have a lot of viable options and he thinks that the king should be on HIS side. for a change. sorry for this posting I spent 2 hours on www.jstor.com today

The most problematic thing about my ocs I think is that crilly and aoife are the only two characters who could be considered politically republican because eoin is, like, basically just a latter-day jacobite, donal and maguire are both kind of just indiscriminately against all government systems, mary would willingly vote for lord castlereagh, and máire legitimately hopes napoleon takes over the entire world. apart from the killings ofc

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

12 October 2015 | Queen Elizabeth II speaks with England Rugby Union head coach Stuart Lancaster and England captain Chris Robshaw during a reception to mark the Rugby World Cup 2015 at Buckingham Palace in London, United Kingdom. (c) Anthony Devlin -WPA Pool/Getty Images

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Part 1 in this series about... something. I’ll figure it out when I write more.

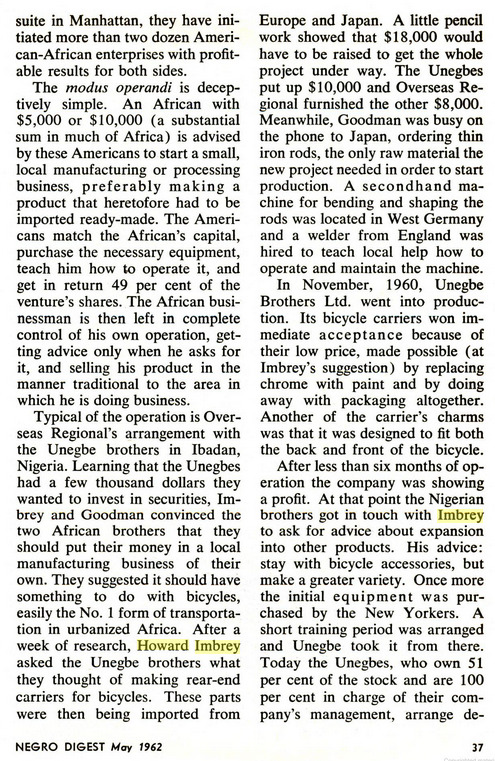

Howard Imbrey was a CIA agent. Having started in the CIA’s WW2 predecessor, the OSS, he was placed undercover in diplomatic roles at American consulates and embassies in Sri Lanka, India, and Ethiopia during the late 40s and 50s. This was a traditional role for intelligence agents: with diplomatic immunity, they would be safe from prosecution, while embassy parties and other events allowed them to pick up gossip from inside the country.

However, it did limit agents and paint a large target on their back. Imbrey operated in a friendly environment in India, where he could rely on British-trained police chiefs as informants in the battle against the Communist Party of India in Maharashtra and Kerala. In other parts of the world, governments would monitor the movements and activities of those who came out of the American embassy, knowing them to be spies.

In 1958, Imbrey was instead embedded in a fake corporation headquartered near the UN in NYC, with a real businessman as his partner. They worked closely with UN diplomats to find actual businesses to promote, to keep the whole thing legit. At the same time, it allowed Imbrey the chance to question the diplomats and businessmen for gossip and to meet with other informants the CIA had already cultivated across the continent. Some of these informants included Cyrille Adoula and Albert Kalonji, head of political parties and breakaway factions devoted to undermining Patrice Lumumba’s elected government in the Congo.

The article attached was important to developing his cover. Initially, it ran in Fortune, owned at the time by Henry Luce’s Time Inc., while the screenshots are from John H. Johnson’s Negro Digest. Luce was historically close to the CIA and the American government in general. He hired CIA agents onto his staff and allowed them to write propaganda as they saw fit. He directed his journalists to publish opinion pieces attacking those who exposed CIA secrets, like Ramparts magazine. At one point in the Congo Crisis, US Ambassador to Belgium William Burden, a friend of Luce’s, phoned him to get him to bury a story on Lumumba. No information has come out either way on just whether the journalist who wrote this article knew Imbrey was CIA or was simply ordered to by higher ups, but it seems likely that the editorial staff of Negro Digest simply saw it as fitting with their focus on black lives and reprinted it unwittingly to the CIA’s benefit. Later on, Imbrey would find another cover as a journalist with a CIA-controlled news outlet in Paris, Brussels, and Rome, which allowed the CIA to fly informants to him.

None of this was known to anyone until 2001, save for a brief acknowledgement of thanks to Imbrey’s wife in a book by Larry Devlin, CIA Station Chief in the Congo. That year, Imbrey suddenly gave two interviews in April and June, and then died a year later. One was to a high school student at a private Episcopal school in Maryland. It’s roughly written, and clearly transcribed by someone who’s writing the names of Congolese officials by ear rather than knowledge, but deserves to be read, not because Imbrey lets his guard down consciously, but rather because of the implicit biases he still has and the distinction between the secrets he wishes to keep and those he feels fine in revealing. Particularly humorous is when the kid tries to ask him about whether the CIA operated independently from the president, and Imbrey denies it, saying “That’s an Arab type of operation.”

The other was to Charles Stuart Kennedy, a career diplomat who retired in the 80s and subsequently made a post-retirement life of interviewing other diplomats for the public record. Since many CIA employees were embedded as diplomats, he ended up running into a bunch. His interview is much more detailed and professional, albeit with the same transcription errors on names, and makes for excellent reading for anybody who enjoys salacious historical gossip. Imbrey talks about reading Popeye the Sailor bootleg Rule 34 as a kid, kidnapping fishermen in the Indian Ocean with submarines to train them to use radios to spy on the Japanese Navy (sounds like UFO abductions), supplying porn to the higher ups in the Indian Navy, etc. But two particular moments stand out, one being what may be the single worst denial of American involvement in the assassination of Patrice Lumumba:

Q: Did you get involved at all with the Lumumba business?

IMBREY: No, the only thing I can tell you is they sent out this shellfish compound to chief of station Larry Devlin and he sent it back with an angry note saying, “Don't you know the Belgians are going to kill him, what do you want us to do?” We kept totally out of that one. Then Lumumba really put himself in terrible trouble when he gave a rise of one rank to everybody in the army and then found he couldn't pay the new prices. Then the army rebelled; they put him in an airplane, took him south and they pulled him out of the airplane on the driveway, brought him up to the chief of the Lunda tribe and in Munongo's office and I guess they shot him there or it may not have been there. In Munongo's office they began asking him a couple of questions. Well, this was according to his answers. Munongo took a bayonet and put it right into Lumumba's chest and Captain Gatt, a Belgian, was right there and he fired a bullet in the back of Lumumba's head to put him out of his misery and that was how it happened, but no Americans were involved.

and whatever this is, which happens to coincide with the CIA’s MHCHAOS operation on American soil:

Q: When you came home what were you doing?

IMBREY: That's where we turn off the tape recorder.

Q: All right, well then, we'll just skip over that. When did you take off again where we can talk?

IMBREY: Let's see. I was sent back to Rome in '72. Turn it off for a while and I'll tell you about it.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Princess Anne photographed wearing the festoon tiara in 1991.

📸 Stuart Devlin

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dark Shadows Ship Tournament: Round Two

Collinsport

Barnabas Collins/Julia Hoffman VS. Quentin Collins/Aristede

Bill Malloy/Elizabeth Collins Stoddard VS. T. Eliot Stokes/Elizabeth Collins Stoddard

Roger Collins/Carolyn Stoddard VS. Julia Hoffman PT/Angelique Collins PT

Carl Collins/Pansy Faye VS. Burke Devlin/Elizabeth Collins Stoddard

Bangor

Angelique Bouchard/Laura Collins VS. Edward Collins/Kitty Soames

Willie Loomis/Jason McGuire VS. Willie Loomis/Maggie Evans

Roger Collins/Victoria Winters/Burke Devlin VS. Roger Collins/Laura Collins

Victoria Winters/Josette Collins VS. Roger Davis/The eternal fires of hell

Augusta

Jenny Collins/Beth Chavez VS. Julia Hoffman/Quentin Collins

Roger Collins/Burke Devlin VS. Carolyn Stoddard/Tony Peterson

Burke Devlin/Victoria Winters VS. Carolyn Stoddard/Victoria Winters

Chris Jennings/Sabrina Stuart VS.Julia Hoffman/Medical malpractice lawsuit

Rockport

Nicholas Blair/Reverend Trask VS. Carolyn Stoddard/Buzz Hackett

Carolyn Stoddard/Maggie Evans VS. Roger Collins/Laura Murdoch/Burke Devlin

Julia Hoffman/Elizabeth Collins Stoddard VS. Quentin Collins/Evan Hanley

Roger Collins/Victoria Winters VS. Jeremiah Collins/Victoria Winters

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is a bowl designed by Stuart Devlin and made by Viners Ltd, Sheffield in 1970.

This was inspired by the moon landing in 1969.

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

Special Tuesday episode--second for July 2021--of the program all about TV. Our guests; Dean Devlin, executive producer of Leverage: Redemption, starring Noah Wyle and coming to IMDb.TV July 9; Stuart McLean, chief executive officer of FAST Studios, a venture developing new ad-supported services for smart TV distribution; Mike Anderson, co-founder and managing partner of OpenGate Entainment, together with TV host and personality Ikill Orion, and Josh da Silva, vice president at Questar, the company behind new travel-oriented programming service Go Traveler. Also, a tribute to prolific episodic TV and film director Richard Donner, who passed away July 5 at age 91.

SPOILERS: just in case Haven’t listened yet!!

I AM Watching Leverage: REDEMPTION for the original cast .. most especially Christian..

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

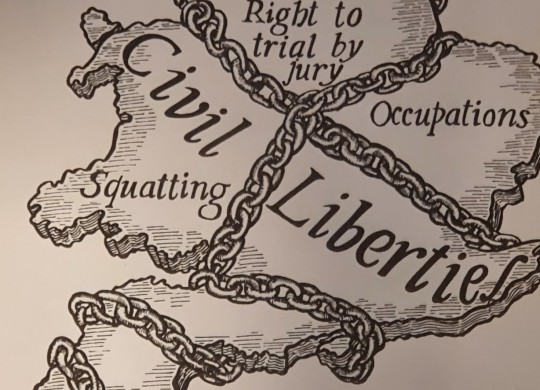

The jury’s “sovereign power of acquittal”

Image: from Haldane Society poster, 1970s

“Each jury is a little parliament. The jury sense is the parliamentary sense. I cannot see the one dying and the other surviving. The first object of any tyrant in Whitehall would be to make Parliament utterly subservient to his will; and the next to overthrow or diminish trial by jury, for no tyrant could afford to leave a subject's freedom in the hands of twelve of his countrymen.” – Sir Patrick Devlin, “Trial by Jury”, Hamlyn Trust, 1956

"If a jury, in despite of law and evidence, were to acquit a felon, he was immediately discharged; such was the wisdom of the constitution in the interposition and augmentation of the powers of a jury, lest the Crown should bear too hard on the life of a subject; nor could a jury be amerced or imprisoned for their verdict." - Thomas Erskine, 1791, House of Commons, in debate on Fox’s Libel Bill

According to the Guardian, Attorney General Suella Braverman “has said she is ‘carefully considering’ whether to refer the Colston statue case to the court of appeal after a jury cleared four protesters of criminal damage over the toppling of the monument.”

Ms Braverman is not famed for the depth of her legal knowledge or expertise; there is no legal basis for intervening in the jury’s free decision to acquit, so she is simply playing to the culture warriors’ gallery. Juries have for centuries decided cases according to their consciences and their overall view of the justice of the case. In 1985, Thomas Green, of the University of Michigan Law School, published a long book entitled “Verdict According to Conscience: Perspectives on the English Criminal Trial Jury 1200-1800” which gives great detail on how juries have acted according to their sense of justice – there is also a vast and disparate literature on the last 221 years of the jury since then! For those interested in the jury, historian E.P. Thompson wrote two excellent articles on the theme in 1986 in the London Review of Books, “Subduing the jury”, and continued here. See also Lady Justice Hallett’s Blackstone lecture on Trial by Jury, given in 2017, in which she underlines the potential role of the jury as

a check against the authority of government and Parliament, which ensures that they take heed of the judgment the public passes on what they do. It is the means by which individuals can ‘feel that the law is theirs’, that the law reflects and continues to be consistent with the ‘attitudes and mores’ of society generally.

In 1956, the judge Sir Patrick (later Lord) Devlin gave the Hamlyn Trust lectures for that year, on the theme “Trial by Jury”. I have cited one of his final passages, at the start of this article. On many issues, he was an out-and-out conservative, so we can be sure that his views on trial by jury were not motivated by political radicalism or (anachronistically speaking) any propensity to woke-ness. Devlin looked closely at the respective roles of judge and jury, and devoted two lectures to “the control of the jury”. He concluded that, in criminal cases, juries have “the sovereign power of acquittal”:

“I do not mean that juries are above the law. They should obey the law. But it is an obedience which they cannot be compelled to give. They are the wardens of their own obedience and are answerable only to their own conscience, so that no man can be convicted against the conscience of the jury.”

That has been the generally accepted position since at least the late 17th century, despite some 18th century disputes (see below) in politically sensitive areas such as prosecutions for seditious libel.

Penn and Mead, and Bushel’s Case

Photo: Via Wikimedia, William Penn and William Mead plaque at the Old Bailey.

(Note: For those interested in a much fuller account of the Penn and Mead case, see the interesting article Jurors v. Judges in Later Stuart Stuart England: The Penn/Mead Trial and Bushell's Case by John A. Phillips and Thomas C. Thompson, 1986, Minnesota Journal of Law and Inequality)

In September 1670, just over 350 years ago, the trial of two Quakers, William Penn and William Mead took place at the Old Bailey. They were charged that they “unlawfully and tumultuously did assemble and congregate themselves to the disturbance of the peace” in Gracechurch Street, London, that they there did preach, and caused a great concourse and tumult of people in the street, to the great terror and disturbance of many of the liege people and subjects of the King, to the ill example of all others. They had been arrested in August for violating the Conventicle Act of 1664, which forbade religious assemblies of more than five people outside the Church of England’s auspices. The defendants did not deny that they were present there, as several eye witnesses told the court. The judges (or so we may infer) considered that the evidence was so conclusive as to bear no alternative interpretation to that of the prosecution.

According to the record of the case in the volume of State Trials, (which - we should note - was written up by the defendants!) the jury’s first verdict was this:

“Guilty of speaking in Gracechurch Street”.

The Recorder (one of the judges) told the jury: “the law of England will not allow you to depart till you have given in your Verdict”, meaning that the jury’s verdict was incomplete.

The foreman replied, “we have given in our verdict, and we can give in no other”.

They were sent away to “go and consider it once more, that we may make an end of this troublesome business”. They shortly returned, and read out the following verdict:

“We the jurors, hereafter named, do find William Penn to be guilty of speaking or preaching to an assembly, met together in Gracechurch St, the 14th of August last, 1670. And that William Penn is not guilty of the said indictment.”

The Recorder responded: “Gentlemen, you shall not be dismissed till we have a verdict that the court will accept: and you shall be locked up without meat, drink, fire and tobacco; you shall not think thus to abuse the court; we shall have a verdict, by the help of God, or you shall starve for it.”

The jury were then held overnight in these conditions, to encourage them to reach a verdict acceptable to the judges. Next morning,

Clerk: “Are you agreed upon your verdict?”

Jury: “Yes”

Clerk: “Who shall speak for you?”

Jury: “Our foreman”.

Clerk: “What say you? Look upon the prisoners at the Bar. Is William Mead guilty of the matter of which he stands indicted, in manner and form as aforesaid, or Not Guilty?”

Foreman: “William Penn is Guilty of speaking in Gracechurch St.”

Mayor: “To an unlawful assembly?”

Bushel: “No, my Lord, no we give no other verdict than what we gave last night; we have we have no other verdict to give.”

This was once more unacceptable to the judges, who (after many exchanges) adjourned the case once more overnight, with a view to a clear and unqualified verdict.

Back in court on the third morning, the Clerk asked again for their verdict in the case of William Penn.

Foreman: “Not guilty.”

And asked by the Clerk whether William Mead be guilty or not guilty, the Foreman stated “Not Guilty”.

Clerk: “..and so say you all?”

Foreman: “Yes, we do so”.

Recorder: “I am sorry, gentlemen, you have followed your own judgments and opinions, rather than the good and wholesome advice which was given you… for this the court fines you 40 marks a man; and imprisonment till paid.”

Edward Bushell, who had been singled out by the judges for particular criticism, stood firm and refused to pay; instead a writ of habeas corpus was issued on his behalf, calling on his gaolers to justify the lawfulness of his imprisonment, or free him.

This led to the hearing and judgment in Bushel’s case (also in 1670, reported in the State Trials edition immediately following the case of Penn and Mead). Chief Justice Vaughan (of the Court of Common Pleas) ordered the Plaintiff’s release, and held that (save perhaps in cases of lack of integrity by jurors) there was no power of the judges to compel jurors to reach a specific verdict.

Chief Justice Vaughan summarised the case against Bushell:

In the present case it is returned, that the prisoner being a juryman, among others charged at the Sessions Court of the Old Bailey to try the issues between the king, and Penn, and Mead,… did ‘contra plenam et manifestam evidentiam’, openly given in court, acquit the prisoners indicted, in contempt of the king &c.” [“against the full and manifest evidence..]

Vaughan continued,

“the court hath no knowledge by this return, whether the evidence were full and manifest, or doubtful, lame, and dark, or indeed evidence at all material to the issue…”

And further,

“Another fault in the return is, that the jurors are not said to have acquitted the persons indicted, against full and manifest evidence corruptly, and knowing the said evidence to be full and manifest against the persons indicted, for how manifest soever the evidence was, if it were not manifest to them, and that they believed it such, it was not a finable fault, nor deserving imprisonment, upon which difference the law of punishing jurors for false verdicts principally depends.” [My emphasis].

The Court unanimously ordered Bushell’s release from custody.

Seditious Libel: Lord Mansfield v The Jury

Photo: Lord Mansfield in robes, 1783 - from painting by John Singleton Copley, via Wikipedia

While the practice of fining jurors for not (as the judges saw it) doing their duty to convict in such cases as Penn and Mead’s generally ceased, following this judgment in Bushell’s Case, disputes between judges and juries in no way disappeared over the 18th century. Many of the contested cases concerned publications considered to be criminally libellous, as promoting sedition. The long career of Lord Mansfield as judge (later and for many years, Lord Chief Justice in the Court of King’s Bench) gives some fine examples of these contests, including his various run-ins with John Wilkes.

Mansfield was, for most of the period of his judge-ship, also a government minister, so we may imagine how little trust in his impartiality defendants and jurors may have held, in cases in which government had an interest. These included the (anonymously written) Junius letters, published from 1769 to 1772 in The Public Advertiser , edited by Henry Sampson Woodfall. Junius attacked both Prime Minister and King, and Woodfall was prosecuted for seditious libel. The case was heard before Lord Mansfield in the City of London in June 1770. Here is the account given by Mansfield’s most recent biographer, Norman S.Poser (2013, McGill-Queen’s University Press, p.256-7):

“Mansfield told the jury that the only question for it to decide was whether Woodfall was the publisher of the letter. This, he said, was a question of fact, but whether the letter was a libel was a question of law for the judge to decide. After deliberating several hours, the jurors took coaches from Guildhall to Mansfield’s home in Bloomsbury Square. Mansfield stood at the door of his parlour and made the jury give their verdict in the hall where the footmen were. The verdict was “guilty of printing and publishing only”, a verdict that stopped short of finding Woodfall guilty of seditious libel. When Mansfield heard it, he turned and withdrew without a word. He refused to accept the verdict and ordered a new trial.”

But even he did not try to imprison or fine the jurors. Before any retrial of Woodfall took place, Mansfield presided in another seditious libel case, against one John Miller, accused of reprinting Junius’s letter to the King. The jurors in this case likewise had to travel to Mansfield’s home to give their verdict, with a large crowd following.

“This time, the jury brought in a simple verdict of ‘not guilty’. It was said that the roar of the crowd could be heard throughout London” (Poser, p.257).

It was now evident that getting a conviction in such cases was nigh-on impossible for the state at that time, and the anonymous Junius turned his guns on to Mansfield:

“I see, through your whole life, one uniform plan to enlarge the power of the Crown at the expense of the liberty of the subject… When you invade the province of the jury in matter of libel, you in effect attack the liberty of the press.” (Junius also went on to attack Mansfield for being too “feminine” in character, a somewhat less glorious or high-principled constitutional complaint). (Poser p.258).

Mansfield, in turn, continued to prove beyond reasonable doubt the accuracy of Junius’s attack; when Woodfall was indicted several years later for seditious libel (this one for disparaging the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688, and the long-deceased King William and Queen Mary), the jury brought in a verdict of guilty of publishing the paper, but not of it being a libel. Mansfield demanded a ‘general verdict’ of guilty or not guilty. The jury simply stated, they found him guilty of publishing the paper. Mansfield then took things into his own hands and – without further reference to the jury - said “That is, you find him guilty”, and fined him 300 marks. (Poser, p.258).

From the Dean of St Asaph’s Case to Fox’s Libel Act

Photo: the Dean of St Asaph, photo via Wikipedia

Even when he was nigh-on 80 years old, Mansfield continued to hold the line that it was for the judges to decide whether a publication was seditious, pretending that this is a matter of law. Curiously, Poser’s biography of Mansfield almost ignores the important case of R v Shipley, often known as the Dean of St Asaph’s case (1784). Here, I take the summary given in an article by Professor Kevin Crosby,

In 1784, William Shipley, the son of St Asaph’s radical bishop Jonathan Shipley, and himself the Dean of St Asaph, was prosecuted for republishing a controversial political pamphlet. William Jones, the pamphlet’s author and a recently appointed colonial judge, was surprised to find a prosecution for the publication of an abstract work of political philosophy was even possible… While an English jury was eventually persuaded to convict Shipley ‘of publishing’ the pamphlet, he was subsequently discharged by the judges of The King’s Bench, owing to the fact that under the prevailing doctrine of seditious libel a guilty verdict was understood as a de facto special verdict, leaving legal questions (including whether a particular pamphlet was actually seditious) to a later judicial determination. This case is primarily famous because of the challenge it posed to this established doctrine…

The pamphlet contained a pretty mild case for Parliamentary and constitutional reform. The case was tried by judge (Mr Justice Buller) and jury in Shrewsbury. The defence lawyer was Sir Thomas Erskine, who challenged the traditional judges’ argument that the jury’s task was only to decide on publication or no. He argued with passion and logic, first, that the publication was in no way seditious, and that he personally agreed with all its sentiments, and second, that it was for the jury to decide, taking account of the judge’s advice on law:

“Questions of libel may now be expected to be tried with that harmony which is the beauty of our legal constitution, - the jury preserving their independence in judging of the intention, which is the essence of every crime, - but listening to the opinion of the judge upon the evidence, and upon the law, with that respect and attention which dignity, learning, and honest intention in a magistrate must and ought always to carry along with them.”

Judge Buller did not go along with this sugar-coated contention, but insisted on the traditional judicial line, and summed up the case accordingly. The jury retired for half an hour before reaching its verdict; when asked “do you find the defendant guilty or not guilty?”, the response was

“Guilty of publishing only”.

Judge Buller responded: “I believe that is a verdict not quite correct. You must explain that, one way or another. The indictment has stated that G. means ‘Gentleman’ , F. ‘Farmer’, the King 'the King of Great Britain’ , and the Parliament ‘the Parliament of Great Britain’ .

Juror: “We have no doubt about that.”

Buller: “If you find him guilty of publishing, you must not say the word ‘only’”.

Erskine then intervenes: “By that they mean to find there was no sedition”.

Juror: “We only find him guilty of publishing. We do not find anything else.”

Erskine: “I beg your Lordship’s pardon; with great submission, I am sure I mean nothing that is irregular. I understand they say, ‘We only find him guilty of publishing.’”

Juror: “Certainly, that is all we do find.”

Buller: “If you only attend to what is said, there is no question or doubt. You say he is guilty of publishing the pamphlet, and that the meaning of the innuendoes is as stated in the indictment?”

Juror: “Certainly”

Erskine: “Is the word ‘only’ to stand part of the verdict?”

Juror: “Certainly”.

Erskine: “Then I insist it shall be recorded”.

Buller: “Then the verdict must be misunderstood; let me understand the jury.”

Erskine: “The Jury do understand their verdict.

Buller: “Sir, I will not be interrupted.”

Erskine: “I stand here as an advocate for a brother citizen, and I desire that the word ‘only’ may be recorded.”

The judge then ordered Erskine to sit down and warned him that he might be dealt with “in another manner”, meaning contempt proceedings.

Erskine: “Your Lordship may proceed in what manner you think fit; I know my duty as well as your Lordship knows yours. I shall not alter my conduct.”

The author of “The Lives of the Lord Chancellors” then comments:

“The learned judge took no notice of this reply, and, quailing under the rebuke of his pupil, did not repeat the menace of commitment. This noble stand for the independence of the Bar would of itself have entitled Erskine to the statue which the profession affectionately erected to his memory, in Lincoln’s Inn Hall.”

A statue that - unlike Colston’s - still stands proudly aloft!

In the end, Buller may be thought to have got the better outcome in this skirmish, however. The jury expressed the wish to withdraw once more, and their final verdict did not contain the word “only”:

“Guilty of publishing, but whether a libel or not, we do not find.”

Erskine applied to set aside the verdict on the ground of misdirection in law, and came before the court comprising three judges, including Lord Chief Justice Mansfield. This hearing is famed first for the argumentation of Erskine, the most complete argument for the role of jurors in reaching general verdicts on the whole case, and second, for Lord Mansfield’s summation of the (reactionary) law and precedents as he saw them to that date. It came as no surprise that the court upheld the traditional view of the respective roles of jury and judge in criminal libel cases, and it appears that Erskine knew he would lose this argument but was seeking to make the case for legal reform

Lord Mansfield, in his judgment, referred to a case of libel (that of a Mr Tutchin) decided by Lord Holt in 1704, which underlined the true rationale – to prevent criticism of government. Here is what Holt said:

“But this is a very strange doctrine to say it is not a libel reflecting on the government, endeavouring to possess the people that the government is mal-administered by corrupt persons that are employed in such or such stations either in the navy or army. To say that corrupt officers are appointed to administer affairs is certainly a reflection upon the government. If people should not be called to account for possessing the people with an ill opinion of the government, no government can subsist. For it is very necessary for all governments that the people should have a good opinion of it. And nothing can be worse to any government than to endeavour to produce animosities as to the management of it; this has always been looked upon as a crime, and no government can be safe without it is punished.” (Source: Stephen’s “A History of the Criminal Law of England, vol II, p.318)

In the event, but much later than Erskine hoped at the time of Shipley’s case, Fox’s Libel Act of 1792 did indeed reverse the Mansfield doctrine, and made the jury the decider of all issues. The Act starts nicely, pretending that the Act’s purpose was simply to “remove doubts” about the jury’s role, while in fact reversing a century of judge-imposed law:

Whereas doubts have arisen whether on the trial of an indictment or information for the making or publishing any libel, where an issue or issues are joined between the King and the defendant or defendants, on the plea of Not Guilty pleaded, it be competent to the jury impanelled to try the same to give their verdict upon the whole matter in issue: be it therefore declared and enacted . . . That, on every such trial, the jury sworn to try the issue may give a general verdict of guilty or not guilty upon the whole matter put in issue upon such indictment or information; and shall not be required or directed, by the court or judge before whom such indictment or information shall be tried, to find the defendant or defendants guilty, merely on the proof of the publication by such defendant or defendants of the paper charged to be a libel, and of the sense ascribed to the same in such indictment or information.

“Inhibitor of oppressive process”

E.P.Thompson underlined (in his LRB articles of 1986) that the jury has not always played a progressive role. Its “sovereign power of acquittal” might on occasion be used for reactionary as well as progressive interpretations of justice. Becoming a juror remained, until 1972, based on a property qualification which had progressively been abandoned in the case of voters, meaning that the jury was not representative of society as a whole (and over-represented men). Thompson argued that the class background of jurors was relevant, even when standing against oppression:

[T]he assumption by the jury of a new and critical role – that of inhibitor of oppressive process and defender of the subject against the Crown or the organs of the state – was the expression of a particular moment (which stretches from the 17th to the early 19th century) when the middling sort of people (from whom juries, and especially London juries, were drawn) found themselves to be repeatedly at issue with the aristocracy and Court.

Later on, he contends, juries tended to side more with the establishment (though this merits closer examination - defence lawyers have almost always preferred trial by jury to trial by judge or magistrate).

I do not know the composition of the Bristol jury in the Colston case, whether of a middling or indeed lower or higher sort of people… but we surely, in today’s England, again need a body capable of playing a constitutional role as “inhibitor of oppressive process and defender of the subject against the Crown or the organs of the state”.

Bristol’s history - redressing the balance

Photo: Via Wikipedia. Stowage of the British slave ship Brookes under the regulated slave trade act of 1788 - part of Thomas Clarkson’s campaign for abolition.

That said, there is something specific about the history of cities like Bristol whose wealth depended so heavily on the slave trade, which makes the jury’s recent verdict all the more understandable, taking the long view. The trafficking was not limited to black African slaves (even if they formed the largest part by far of the evil trade). Even Judge Jeffreys, who so savagely pursued those who took part in Monmouth’s uprising against James II, seems to have been shocked by some Bristolian practices against petty criminals, which came close to imposing a form of slavery on such “commodities”. This passage from Roger North’s “Lives of the Norths” I came across in Holdsworth’s “History of English Law” :

There had been an usage among the aldermen and justices of [Bristol] (where all persons, even common shop-keepers, more or less trade to the American plantations) to carry over criminals who were pardoned with condition of transportation, and to sell them for money. This was found to be a good trade; but, not being content to take such felons as were convicts at their assizes and sessions, which produced but a few, they found out a shorter way which yielded a greater plenty of the commodity. And that was this. The mayor and justices, or some of them, usually met at the tolsey (a courthouse by their Exchequer) about noon, which was the meeting of the merchants as at the Exchange in London; and there they sat and did justice business that was brought before them. When small rogues and pilferers were taken and brought there, and, upon examination, put under terror of being hanged, some of the diligent officers attending instructed them to pray transportation, as the only way to save them; and for the most part they did so. Then no more was done; but the next alderman in course took one and another as their turns came, sometimes quarrelling whose the last was, and sent them over and sold them.

These iniquitous practices came to the knowledge of Jeffreys. He found that all the aldermen and justices were concerned in it, and “the mayor himself as bad as any.” He compelled the mayor “accoutered with his scarlet and furs” to “go down to the criminal’s post at the bar”, and ended by taking security of the mayor and older men to answer informations. But interest was made at court, and Jeffries was induced not to press the prosecutions.

The prosecutions depended till the Revolution [1689] which made an amnesty; And the fright only, which was no small one, was all the punishment these juridicial kidnappers underwent; and the gains acquired by so wicked a trade rested peacefully in their pockets.

Vol XI (1st edition) p.572]

I know of no evidence that Edward Colston was involved in this corrupt form of domestic human trafficking for profit to the plantations. He was in his 50s at the time, and may well have been too busy in the wholesale (industrial-scale) slave trade of Africans to concern himself in Bristol’s homespun retail ‘trade’. But in one way or another, Bristol’s ruling elite were united in their quest to get rich on human trafficking, from the late 17th century through to the 19th (and many of their successors received ‘compensation’ for loss of slave ‘property’ in the 19th century, paid for by the British taxpayers).

The fearsome Judge Jeffreys was blocked by lobbyists at “court” from stopping the domestic slave traders in his day. The international slave traders, Colston and his successors, had well over 100 years of mass human trafficking of Africans, in which so many thousands died, unrecognized victims of murder and manslaughter.

It has fallen to a 21st century Bristol jury to begin to redress the balance, in a small but symbolic way.

2 notes

·

View notes