#XVIe siècle

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

[Ensemble de gravures de costumes d'Allemagne du XVIe siècle] : [estampe]

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

François I received a book in the presence of his mother, Louise de Savoy, and sister, Marguerite d’Angoulême.

Date: 1503.

Source: National Library of France

Description taken from here:*

“Master of Philippe de Gueldre, "Antoine Vérard presents his book to François d'Angouleme, in the presence of Louise de Savoie and Marguerite d'Angoulême, in Octavien de Saint-Gelais, Le Séjour d'honneur, Paris, Antoine Vérart

BnF, Rare Book Reserve, Venom 2239, fol. 1st

In 1506, after his engagement to Claude de France, daughter of Louis XII, François d’Angouleme is summoned to court as heir to the throne. It is no doubt on this occasion that the Parisian bookwire Antoine Vérard is preparing for him a personalized copy of his edition of the Séjour d'Honneur, allegory describing the court of Charles VIII. In the light of dedication, the young prince receives the volume of Vérard's hands, under the gaze of his mother, Louise de Savoie, and a young girl who is undoubtedly his sister, Marguerite.”

*facebook group entitled “enluminures Europe—VIe -XVIe s.”

#16th century France#16th century#XVIe siècle#enluminures#Valois-Angoulême dynasty#Valois dynasty#House of Valois#House of Valois-Angoulême#Maison de Valois#Maison de Valois-Angoulême#Louise de Savoyie#Louise of Savoy#marguerite de navarre#Marguerite d’Angouleme#François Ier#François I#Francis I of France#François de France#primary sources#illuminated manuscript#Louis XII#claude de france

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

LAVINIA FONTANA (1552 – 1614)

Lavinia Fontana est née à Bologne le 24 août 1552 dans une famille d’artistes. Son père, Prospero Fontana, était un peintre en vue à Bologne. C’est dans son atelier qu’elle étudie la théorie de la peinture avant de passer à la pratique. Elle profite également de l’ébullition artistique de la ville de Bologne pour exercer son regard en observant des œuvres de Raphaël (1483 – 1520) ou du Parmesan (1503 – 1540).

En 1577, alors âgée de vingt-cinq ans, elle épouse Gian Paolo Zappi, peintre tout comme elle. L’histoire aurait pu s’arrêter là : à cette époque, dans les couples d’artistes, c’est la femme qui stoppe sa carrière au profit de celle de son mari. Chez les Zappi-Fontana, les choses sont différentes. Gian Paolo cesse de peindre pour servir d’assistant à Lavinia. Il s’occupe de lui trouver des mécènes, gère les commandes et exécute certaines finitions dans ses tableaux. C’est le cas notamment des draperies. Ainsi, malgré ses onze enfants – dont seulement trois lui survivront – Lavinia arrive à mener sa carrière à bien.

Celle-ci est exceptionnelle, surtout pour l’époque, puisqu’elle réalise des commandes privées et publiques. Lavinia Fontana est ainsi souvent considérée comme la première femme à s’être forgé une carrière d’artiste indépendante.

Lavinia Fontana ne souhaite cependant pas se limiter aux portraits. Elle réalise des tableaux religieux, notamment un Noli me tangere en 1581 (Galerie des Offices, Florence). Passer ce cap est une première étape sur son ascension : elle attire finalement l’attention du pape Grégoire XIII qui lui commande un portrait (non daté). Malgré le soutien pontifical, son œuvre est victime de controverses liées à son genre. En 1600, le cardinal d’Asconti lui commande en effet un grand tableau d’autel pour l’église Sainte-Sabine à Rome. Cette décision provoque de nombreuses polémiques : qu’une femme exécute des commandes privées passe encore. Mais une commande publique, de si grande échelle de surcroît… Cette idée semble impossible pour de nombreux opposants qui jugent une femme indigne d’une telle responsabilité. Le cardinal, appuyé par le pape, maintient sa décision. Lavinia Fontana, elle, résiste à la pression. Le succès de son tableau est finalement tel qu’en 1603 elle s’installe à Rome.

La peintre poursuit alors son œuvre, alternant portraits privés, tableaux religieux et même mythologiques. Lorsqu’elle peint en 1613 sa Minerve s’habillant (œuvre ci-dessus), elle est l’une des premières femmes à oser la représentation du nu féminin.

À sa mort le 11 août 1614, elle laisse une œuvre de 131 tableaux (dont plusieurs sont malheureusement perdus). Mais au-delà de sa propre création, Lavinia Fontana laisse derrière elle un héritage tout aussi important : le chemin qu’elle a tracé. En étant élue à l’Académie des Beaux-arts de Rome, elle prouve à tout le monde qu’une femme peut être plus qu’une femme d’artiste, mais bel et bien devenir artiste femme.

Pour en savoir plus :

Lavinia Fontana | Renaissance, Female Artist & Bologna | Britannica

Lavinia Fontana : l’artiste peintre du XVIe siècle dont le mari est l’assistant (radiofrance.fr)

Artistes femmes, Flavia Figeri, 2019, Flammarion, p.10-11

Pour voir une œuvre de Lavinia Fontana en France, vous pouvez vous rendre au château de Blois et admirer le portrait saisissant d’Antonietta Gonzalvus, une jeune fille atteinte d’hypertrichose.

#peintre#artiste femme#women artists#women in art#history of art#italy#lavinia fontana#xviiie siècle#xvie siècle

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#i just found this in my old photo files#i made it during my second year and people on twitter thought it was real#i wish it were#rabelais#xvie siècle

0 notes

Text

La Céramique à travers les âges : Le XVIe siècle

Le XVIe siècle marque une époque florissante pour l'art de la céramique à travers le monde. Chaque région développe ses techniques et esthétiques propres, influencées par des échanges commerciaux et culturels intenses.

#Alain Prévet#Bernard Palissy#Céramique#Château d&039;Ecouen#Château de la Bâtie-d&039;Urfé#François 1er de Médicis#Guido Andriez#Histoire#Jingdezhen#Loges du Vatican#Masséot Abaquesne#XVIe siècle

0 notes

Text

Celle qui parle

Titre : Celle qui parle Auteur/Autrice : Alicia Jaraba Éditeur : Grand Angle Date de publication : 2022 (mars) Synopsis : Fille d’un chef déchu, offerte comme esclave, elle est devenue l’une des plus grandes figures féminines de l’Histoire. XVIe siècle. Malinalli est la fille d’un chef d’un clan d’Amérique centrale. Peu de temps après la mort de son père, elle est vendue à un autre clan pour…

#biographie#civilisation précolombienne#féminisme#Grand Angle#guerre#littérature espagnole#viol#XVIe siècle

0 notes

Text

`1TEFAF 2024-2 - Toujours les femmes

TEFAF 2024 - my second and last blog about this fascinating art fair. It's huge, so forgive me if I didn't see all of it, and will give you here a very personal, subjective description...

View On WordPress

#16th century#19th century#20th century#ancient art#antiques#antiquités#art#art ancien#art fair#art sales#Maastricht#modern art#Pays-Bas#TEFAF#TEFAF2024#vente dárt#XIXe siècle#XVIe siècle#XVIIe siècle#XXe siècle#XXIe siècle

0 notes

Text

"Cœur, airs de cour français de la fin du XVIe siècle", by Le Poème Harmonique Listen: https://ift.tt/UDzTkBe *Cœur, airs de cour français de la fin du XVIe siècle* by Le Poème Harmonique is a delicate exploration of the lyrical intimacy of 16th-century France, where every note feels like a whispered secret. The ensemble's deft interplay evokes a courtly dance, each piece a miniature world of emotion and elegance. The instrumentation, both lush and restrained, mirrors the nuanced sentiments of the era, weaving a rich soundscape that invites reflection. Vocal performances soar with a clarity that seems to transcend time, grounding the listener in a melodic embrace both haunting and tender. Here, the air is thick with courtly intrigue, and the harmonies resonate with the weight of history. Le Poème Harmonique crafts not just music but an experience—a portal into a bygone realm where every sigh and cadence beckons to be savored. In this album, beauty and melancholy coexist, leaving an indelible mark on the listener's soul.

0 notes

Text

Les grands peintres : L’École espagnole du XVIe siècle : L'âge d'or espagnol.

Contexte historique Charles Quint Le siècle d’or correspond à la période de rayonnement culturel de la monarchie catholique espagnole en Europe du XVI au XVII siècle (1492-1681).Elle débute avec l’Empereur Charles Quint (qui est le plus grand monarque Européen de cette période et s’achève avec Philippe IV (1621-1665) soit environ 110 ans.Lorsque Charles Quint abdique en 1555, épuisé et malade,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Portrait of Charlotte Robespierre, in Collection d'autographes, de dessins et de portraits de personnages célèbres, français et étrangers, du XVIe au XIXe siècle, formée par Alexandre Bixio

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

Un peu d’histoire… L’œuf, dans l’Antiquité, symbolise la fécondité et par extension le renouveau et la renaissance, une symbolique à laquelle l’Église n’est pas insensible. Elle interdit la consommation de ce riche aliment, dès le IIIe siècle, durant toute la période du Carême (interdiction levée au XVIe siècle).

Mais les poules l’entendent d’une autre oreille et continuent de pondre. L’habitude est alors prise, le jour de Pâques, de disposer sur la table de fête, les œufs pondus depuis 40 jours. Une abondance qui symbolisait la fin des privations.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Statue de Saint Juvin, XVIe siècle, Eglise de Saint Juvin, Commune de Saint Juvin, Champagne Ardenne, France

#Saint Juvin#sculpture#16th century#Renaissance#archeology#art#art history#history#Europe#France#Champagne Ardenne#Ardennes#Commune de Saint Juvin

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Once you have seen it, you cannot unsee it anymore: a cartoon of the British businessman Cecil Rhodes, published in the Dec. 10, 1892, edition of Punch magazine. The cartoon, drawn by Edward Linley Sambourne, is called “The Rhodes Colossus.” It depicts Rhodes, a late 19th-century diamond-mining magnate in South Africa who used his fortune to help the British expand their empire, as a giant in a colonial outfit towering over Africa, a gun slung over his shoulder, with one booted foot firmly planted in Cairo and the other in Cape Town. He holds a telegraph line in his hands. In a phase of accelerated, furious imperialism at the end of the 19th century, when European powers raced to conquer much of Africa, Rhodes planned to build a rail and telegraph line from Cape Town to Cairo, connecting all British African colonies like beads on a string.

You cannot unsee the cartoon, because today, in our time, Elon Musk is to U.S. President Donald Trump more or less what Rhodes was to the British Empire in his day: an oligarch with far-reaching powers and liberties bestowed on him by the state to help it grab as much of the world’s land, waterways, resources, and labor as it can before someone else does.

In 1906, in an introduction to the translated writings of the influential American Navy officer Alfred Mahan, a French philosophy professor named Jean Izoulet described the mood back then as follows: “Indeed, the Earth is round; it is a domain, an island in space. (…) More and more people live on this limited territory. Supply is limited, while demand is infinite. According to the law of supply and demand, the price of a meter of land on this small celestial body, if I may call it that, is rising rapidly. Groups of people will fight over territory, over a place under the sun.” Musk could have said something similar.

The zeitgeist that Izoulet describes is similar to ours. He and Rhodes, like all of us today, lived at a time when liberal capitalism was transitioning into what might be called predatory capitalism. In a liberal capitalist system, competition is a key element. It is about people and companies creating things they exchange or sell to each other. The idea is that there is plenty of space for everyone. Everyone, in theory at least, should be able to get a little piece of the pie. In the world of liberal capitalism, moreover, there are rules that apply to all.

Predatory capitalism is the stage that can follow, when the feeling of abundance gives way to an acute sense of scarcity, and when exchange changes into conquest. At least, this has already happened twice before in history—in the 17th and 18th centuries, and at the end of the 19th century—and now it seems to be happening again, according to a remarkably lucid book just published by French economist Arnaud Orain: Le monde confisqué; Essai sur le capitalisme de la finitude (XVIe-XXIe siècle).

Orain, a professor at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris, sheds an interesting light on the significance of Trump’s election. He does this by focusing on, and describing in detail, those two earlier periods in history when predatory capitalism raised its head after long phases of much milder liberal capitalism. The book, which has not yet been translated into English, also connects many of the characteristics of the second Trump presidency with things happening in those two periods, placing them in a broader context.

This context is helpful. From Trump’s territorial claims on the Panama Canal, Canada, or Greenland to his constant bullying of closely allied nations or to the greedy billionaires who helped him to get elected and now want to meddle with foreign countries in the name of the world’s most powerful state—today, all this may seem outrageous and almost unreal, but the two earlier predatory capitalist phases were characterized by the same kind of frenzy, hubris, and imperial behavior.

Orain argues that liberal capitalism became a “capitalism of finitude” around 10 years ago, via an intermediary, neoliberal stage (when the rules-based order started to malfunction and partly break down). What defines the capitalism of finitude is that, suddenly, competing powers convince themselves there is not enough for everyone on Earth. So, they unleash a cutthroat rivalry. Existing rules, international treaties, and codes of conduct are furiously cast aside in order to take the world’s waterways, land, resources, data, and human labor—anything they find useful to expand their power.

It is not just Trump and his digital billionaires who do this. It is also Israel, waging all-out war against Gaza and bombing Lebanese villages without any of the restraint that characterized the Israeli military in previous decades, and in total disregard of international law. It is Russia invading its neighbors because President Vladimir Putin wants the old empire back, using former Wagner Group militias to get to Africa’s minerals, and trying to expand its holdings on Spitsbergen (which belongs to Norway) and dominate the Arctic. It is China, too, creating facts on the water in the South China Sea, and being hard at work to establish semi-colonial “stations” in strategic ports and get ownership of arable land (in the book, they are called “ghostly hectares”), plantations, and mines on other continents. The list gets longer by the year.

This is a zero-sum game: If you don’t get something, someone else will snatch it. Orain, the author, is not a Marxist. His tone is descriptive, not activist. He says he finds inspiration in the works of early 20th-century French historian Fernand Braudel, who once taught at the same university and famously argued, among other things, that during a liberal capitalist phase you have an “economy,” but during a predatory capitalist phase there are only “monopolies.” In such a period, everything becomes political. Land, rivers, and resources are seized. The free market becomes obsolete. Multinationals serve as the long arm of the state.

Seen this way, the function of Musk’s empire for Trump is similar to that of Huawei or Cosco, the shipbuilding giant, for Chinese President Xi Jinping. It also resembles the relationship between the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) and the Dutch Republic in the 17th and 18th centuries in the first phase of the “capitalism of finitude” that Orain identifies and describes. The VOC was given a huge trade monopoly by the state: The Dutch government allowed it to build and conquer forts in many parts of the world, to negotiate and sign trade agreements, to mint coins—even to wage war.

What had started during the “moderate” liberal capitalist phase with trading posts in strategic places (from Suriname to what is Indonesia today)—where European fabrics and other things were exchanged for spices, for example—turned into hard oppression and expropriation. There was no longer any (semblance of) exchange, just occupation and extraction. In the hunt for the world’s riches, the VOC had almost carte blanche. Two centuries later, after a period of relatively benign liberal capitalism during the mid-19th century, things escalated again around 1870. A murderous race ensued among European superpowers for land, waterways, raw materials, and human capital. They trounced each other, using existing or newly established companies to get the upper hand.

The detailed descriptions and many citations from old books and records make clear that in such periods, the world becomes extremely unsafe for everyone. Hubris and raw power dominate everything. Those too weak to join the race risk losing out completely.

Halfway through the book, Rhodes is quoted in despair, looking at the sky at night, seeing all those stars he cannot get to: “These vast worlds that will forever be out of reach. If I could, I would annex them.” Musk, who has said he wants to “colonize the whole solar system,” is not mentioned here. No need, even. By now, the picture comes up automatically: Musk in a colonial outfit, one foot on Mars and the other on some other planet, a gun slung over the shoulder.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

🏰 Le Château d’Alden Biesen

La commanderie d'Alden Biesen était un monastère-château de l'ordre Teutonique et le siège de la grande commanderie des Vieux-Joncs, dont le nom latin était Balivia de Juncis, un des douze grands bailliages du gouvernement de l'ordre teutonique du Saint-Empire romain du XIIIe siècle à la Révolution française. Entièrement rénové, c'est aujourd'hui un centre international de conférences.

Ensemble architectural construit du XIIIe au XVIIIe siècle par l'ordre des chevaliers Teutoniques dans l'ancienne principauté de Liège, ce domaine et son château sont situés dans la province de Limbourg de Belgique. Le domaine est offert en 1220 à l'ordre des chevaliers Teutoniques, une confrérie hospitalière allemande, devenue ordre militaire. Du XVIe siècle au XVIIe siècle, l'ordre construit ce château et au xviiie siècle, un des derniers commandeurs va le transformer en résidence de style baroque tardif agrémentée d'un parc à l'anglaise. Après un violent incendie, en 1971, le site est classé en 20001, entièrement restauré, et aménagé en centre de conférence international. Son ancien hospice est aujourd'hui une brasserie.

#castel#château#bilzen#belgium#history#photo#photography#shot on iphone#original photographers#photographers on tumblr

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

Did Prieur Claude Antoine really have a daughter with Madame Vêtu in 1788 (or is it just a strong possibility)?

Whether Prieur had a daughter with Catherine-Elisabeth Vétu, born Joly, is something we can never know for sure, unless we go back in time and ask them. However, according to both Paul Arbelet and Georges Bouchard, who had the chance of having access to Prieur's complete collection of personal papers, there's strong evidence that the latter might have truly been the biological father of Madame Vétu's last child.

Before delving into the matter, allow me a little digression on how Prieur and Catherine came to know each other.

The two met in 1785, when he was 22 and she was 29; yes, she was seven years older than him! The former moved to Dijon both for military duty and to assist Louis-Bernard Guyton in his scientific works. The young officer needed a place to stay and one of the rooms of the Vétu family house revealed itself to be the most suitable for him. Bouchard guessed that the two might have become close very soon, allowing Prieur to eat and sleep there for free since his low salary at the time wouldn't have allowed him to always pay the rent. (1)

Not a far-fetched speculation, considering Catherine’s lively character and active participation in the management of her husband's grocery store; at that time managing a business implied a minimum of education and both a strong dedication and commitment to work; qualities that Prieur appreciated and admired in a person. On the other hand, Catherine, despite the age gap, must have been impressed by Prieur's reserved, hardworking character and polite manners, something that her husband seemed to be lacking. (2)

In 1785 Catherine already had two children, Pierre, 9 years old and Bernard, 7 years old; three years later, her last one, Claudine was born. Prieur was chosen as godfather, or offered to be.

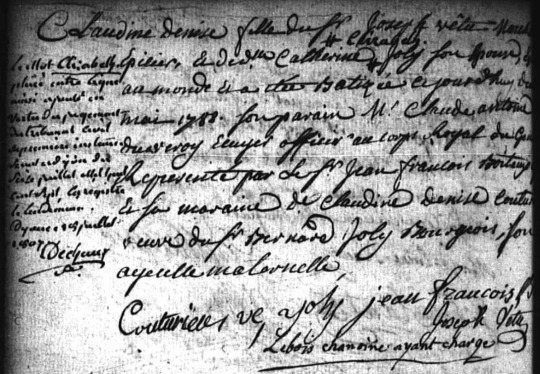

Here's the child's baptism certificate I managed to find in the Cote-d'Or archives:

[Source: Archives de la Côte-d'Or, Registres paroissiaux et état civil, XVIe siècle-1938 (sous-série 2 E). Collection communale 1579-1792, Toutes paroisses, FRAD021EC 239/095, Vues 0252-0317 : Paroisse Saint-Jean, Baptêmes et Mariages, janvier 1788-décembre 1788, vue 279]

Claudine-Denise, fille du Sr Joseph Vétu, marchand épicier et demoiselle Catherine Joly son épouse, est venue au monde et a été baptisée ce jourd'hui 2 mai 1788, son parrain, M. Claude-Antoine Prieur Duvernoy, écuyer, officier au corps royal du génie, représenté par le Sr Jean-François Boiteux, épicier, et sa marraine, dame Claudine-Denise Couturier, veuve du sieur Bernard Joly, son aïeule maternelle. (3)

EN: Claudine-Denise, daughter of Joseph Vétu, grocery merchant and of Catherine Joly, his spouse, was born and baptized on this day 2 May 1788, her godfather being M. Claude-Antoine Prieur Duvernoy, esquire, officier in the Corps Royal du Génie, represented by Sr. Jean-François Boiteux, grocer, and her godmother dame Claudine-Denise Couturier, widow of Monsieur Bernard Joly, her maternal grandmother.

As mentioned before, the supposition that Claude-Antoine might have been more than a simple godfather stems from some facts that for Arbelet and Bouchard are pretty emblematic: In Prieur's personal notes, there's a date written down by him and another one right next to it, which not only corresponds to Claudine's birthday, but it's curiously nine months distant from the first date. I’m not an expert on 18th century customs, but it’s not unlikely that men wrote down the date in which they had intercourses with a woman to know if they were the father of the child that might have later been born. When Claudine was 17, Prieur arranged a marriage between her and a friend of his, Drappier, to whom he later associated the business the former was running at the time; at the time these engagements for a girl were her father’s or her guardian’s duty. When Prieur wrote his testament, he left quite a sum of francs to Claudine's son as inheritance and lastly, there's also a letter from an old garrison fellow of Prieur, in which there's written "I wish good morning to you and your women". (4)

I’d like also to add that from the bits of their correspondence shared by Bouchard and the overall treatment Prieur reserved for her throughout her life, the two seemed to be pretty close, linked by an intimacy that goes beyond the one between a woman and an old family friend. He was always there for her, sent her various gifts and helped her financially. In my opinion, this further confirms the hypothesis that Claudine was his real daughter.

Why did he never adopt her, not even after Joseph Vétu’s death? It’s a question that those who wrote about Prieur never asked themselves, but that I personally wonder. The only thing I can think of right now, given my limited knowledge, is that he didn’t want to give her his surname and cause her to be persecuted. Despite never being the target of slander, he had been part of the revolutionary government responsible for the Terror and not a normal one, but a member of the “bloodthirsty Committee of Public Safety of Year II”: so was the view of the Great CSP during the Napoleonic Era and Restoration.

It’s Prieur himself that in a letter dated 1814 to General Marescot reveals he resigned from public life at the beginning of the century because he foresaw the persecution the members of the government prior to the Consulate would have endured. (5) If he had had a concern for his daughter, it would have been a legitimate one: Sadi Carnot couldn’t advance in the army, despite deserving it, and was denied some positions, because of the surname he bore.

Edit: thanks to @nesiacha 's detailed answer about inheritance and legitimate/illegitimate children during the First Empire a more plausible reason why Prieur decided not to legally adopt her lies in the fact that Claudine not only wouldn't been granted the same rights as a natural child as far as inheritance was concerned: she would have received significantly less; but also illegitimate children were often viewed in a very hostile and negative way, in some instances, even considered as "monstrosities in the social order" and a "real calamity for morals". He clearly didn't want to stain Claudine's honour. Last but not least, Prieur and Catherine-Elisabeth never married after Joseph Vétu's death and the latter recognised Claudine as his daughter when she was born, so I don't think it would have been easy for Prieur to pass over this.

References

G. Bouchard, Prieur de la Côte-d’Or, 1946, p. 54-58.

P. Arbelet, La jeunesse de Prieur de la Côte-d’Or, Revue du dix-huitième siècle, 1916, p. 38-51

Notes

Curiously in their correspondence, Claudine always calls Prieur "mon cher parrain" (= my dear godfather) and nothing in those letter hints at the fact she might have known her real father's identity.

On page 56 of Prieur’s biography, Bouchard affirms with confidence that the date of Thursday 1 December 1785 which Prieur wrote in his “Tableau du temps... depuis 1782 jusqu'en 1792.” - a sort of list of the main events of his life - corresponds to the latter’s unofficial engagement with Catherine. Considering that Prieur arrived in Dijon in August, it means it took them four months to fall in love with each other. Though, except for a vague remark on “a certain number of coincidences that would be too long to report”, Bouchard doesn’t explain in specific how he got to that conclusion.

From some letters and papers that Prieur kept, Joseph Vétu appeared as a “lousy and insignificant man” (G. Bouchard, p. 56).

Transcription by Bouchard (p. 58 of his biography)

Letter from Andréossy to Prieur (G. Bouchard, p. 361).

Letter to Marescot of 18 April 1814 (G. Bouchard, p.380-381).

#claude antoine prieur#claudine denise vetu#prieur de la cote d'or#claude antoine prieur duvernois#prieur duvernois#frev#prieur de la côte-d'or

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peines de mots perdus

Titre : Peines de mots perdus Auteur/Autrice : Jean-Laurent del Socorro Éditeur : Argyll Date de publication : 2024 (mars) Synopsis : France, 1593. La chance a tourné pour les membres de la compagnie du Chariot : les voilà désormais enfermés à la prison de Rennes. Contre leur libération, leur capitaine Axelle de Thorenc est envoyée sur ordre du roi Henri IV en Angleterre pour retrouver le sceau…

View On WordPress

#Angleterre#Argyll#complot#de cape et d&039;épée#époque moderne#féminisme#littérature française#mercenariat#occultisme#politique#société secrète#théâtre#XVIe siècle#XVIIe siècle

0 notes