#and also how repetition renders something both funny and serious

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The scene at the beginning of s2e8 of Our Flag Means Death is comic, but the resonance with s1e6 ...

So much of Ed's trajectory as a character is about grappling with his need to respond to his own father's violence. He walked away from piracy in part because safety in that life required controlled, strategic violence, which has had great personal costs to him forever.

"Control your Pop-Pop," as silly as it is, is a request for an intervention and protection he didn't get when he was younger. It's not that he can't protect himself-- we know he very well can-- but I think he wants a do-over of his interactions with his father that doesn't leave him feeling alone.

I think "Control your Pop-Pop" is also self-directed in a couple of ways: to his young self, who is still within him and traumatized, and to his current self, who is trained to respond to threat with a strategic violence that would be overkill here.

A little later, Ed makes his second Bond girl entrance of the series, emerging in the leathers he had just buried at sea. We've been hearing the noise in his head for a bit, since he sees the wreckage of ships in the harbor and immediately fears that Stede is dead. Among the static and the dim sounds of British sailors dying in his hands, there's a distorted version of Voi che sapete playing, which of course is what The Swede was singing the night Ed had a flashback to killing his father, behind Stede's narration:

Stede-- or Ed's fear for Stede, or horror at having promised to kill Stede-- calls up the kraken in s1e6, inadvertently triggering Ed. And it's Ed's fear for Stede in s2e8 that returns him to the scene where he buried his old life, to dig it up for the occasion.

Poor Ed has a lot going on in the season 2 finale, and I hope he's enjoying some restorative warm blankets, good food, and orgasms.

#ofmd s2 spoilers#parallels#edward teach#kraken#on the impossibility of controlling your pop-pop#and also how repetition renders something both funny and serious#ofmd mini-meta#ofmd s1e6#ofmd s2e8#our flag means death

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Episode 110: Onion Gang

“No more weirdo friends.”

There have been a handful of Steven Universe episodes that I only watched once, didn’t like, and didn’t watch again until reviewing them for this project. Time has been kind to many of them: I’ve come to appreciate Ronaldo (especially in Rising Tides, Crashing Skies, which I was super down on) as well as Say Uncle and The New Lars. I don’t necessarily love all these episodes now, but they’re a lot better than I once thought.

But yeah sometimes my first impression is right on the money.

Onion Gang is the most boring episode of the series by a country mile. The show has meandered before in the likes of Cat Fingers, Steven’s Lion, and Open Book, but these stories at least resolve in interesting ways. Looking forward, Escapism has even fewer words than Onion Gang, but it’s designed to simultaneously add to Steven’s many ordeals and act as the calm before the storm (and it’s also, y’know, watchable; silence can be a good thing, ask any episode of Samurai Jack). But Onion Gang is relentlessly uninteresting throughout.

The glacial pace isn’t helped by comedy bits falling flat at a rate that’s almost impressive. I try pretty hard to find things I like in episodes I don’t, but there’s literally nothing here for me. That is not easy. Especially considering how much of a sucker I am for Onion, slapstick, and weird goofy side adventures. This should be right up my alley, but hoo boy is it not.

Still, I’ll give it a try: the most generous reading of Onion Gang is that it focuses on Steven misunderstanding Onion, and if you squint, you can draw a parallel between his assumptions about Onion and his assumptions about Rose (both silent, mysterious figures in his life) being proven wrong. False narratives are a recurring theme in Steven’s arc, and another one pops up here. But even if that broadest of strokes is an intended connection, it doesn’t stop Onion Gang from being a catastrophe.

The only Onion Pal that leaves any impression is Garbanzo, and the impression is that Garbanzo is the worst character the show has ever produced. Villains like Kevin and Aquamarine are horrible, but that’s the point. Irritating secondary characters like Ronaldo and Lars have actual depth, and otherwise further the plot and are reliable for decent humor at times (it’s a shame that only one of them grows, but still). Garbanzo is a kid who shouts the word “Garbanzo” as if this is inherently amusing, and uh that’s it. The joke isn’t funny the first time, and doesn’t become funny through brute force repetition. It’s just annoying.

Squash, Soup, and Pinto are...there? They mostly exist for the gag of Steven naming all of them, a continuation of his unusually domineering presence in Onion Gang. Because oh yeah, on top of everything else this is a dreadful Steven episode. It’s not Sadie’s Song, because his presumptuous attitude doesn’t cause actual harm, but this is a bad look on a hero whose powers are supposed to be based on empathy. His narration of Onion’s actions mostly acts as another gag, and like Garbanzo, it’s not a funny one, but that doesn’t stop the episode from repeating it ad nauseam.

Steven’s weird behavior doesn’t stop there. The overlong go-kart scene ends with Steven seeing Garbanzo spray ketchup on himself, then instantly forgetting he saw this and openly wondering if Garbanzo is hurt. Which makes this the dumbest Steven has ever been. It makes zero sense that he would be bamboozled by something he saw faked with his own eyes, to the point where the gag itself becomes confusing: this would be like if he saw Amethyst eat his dinner then asked where his dinner went, it requires Steven’s intelligence to plummet so perilously that it confounds what we’re supposed to find funny about the joke in the first place.

But the most bizarre misfire by far is Steven declaring that he’s “the lonely boy with no friends his age” when Connie Maheswaran exists. She’s busy (as is the underused Peedee), but our hero makes the flying leap that this means he’s utterly friendless. This is a kid defined by his ability to make friends. He saves the ocean once and the planet twice by making friends. The entire show hinges on his fundamental friendliness. This plot point is ludicrous, even when we take into account that Steven is being annoyingly melodramatic.

A nitpick, but one that fuels the Ronaldo-level conspiracy theorist in me, is that Connie was prepping for school in Buddy’s Book and is attending school in Mindful Education, so if she’s shopping for school supplies in Onion Gang then either she’s doing it super late (which doesn’t sound like something she or her mother would ever allow) or this episode, which mind you is stated to take place as summer ends, should've aired between the two Connie episodes. The conspiracy theory is that Onion Gang would’ve looked even weaker when shoved between two episodes about what good friends Steven and Connie are, so it got moved to settle between two Crystal Gem stories.

I think that it’s theoretically possible to make a good episode that evokes unambiguous pathos from Onion. But considering the character works because he’s this strange, menacing force of nature in an otherwise pretty normal population of humans, I’m not sure he’s a character that needs the depth. Onion Friend hit a sweet spot of making him grow a little, but maintain his creepy charm. Onion Gang goes further, but in doing so removes everything interesting about Beach City’s resident weirdo. Gone is the kid who two episodes ago was robbing the arcade with a crowbar and a bandit mask. Here instead is an odd but sensitive kid whose mischievous friends somehow render him less mischievous than usual. It’s bad enough to have a boring episode, but a boring episode with Onion as the focus? Again, it’s almost impressive.

There’s no reason to watch this episode instead of any other Onion-centric episode if Onion is your jam. There’s no reason to watch this episode instead of any other Steven-centric episode barring Sadie’s Song if Steven is your jam. There’s no reason to watch this episode instead of rewatching Last One Out of Beach City if being charmed by friendship is your jam. There’s no reason to watch this episode instead of Buddy’s Book if thematic resonance in regards to false narratives is your jam. There’s no reason to watch this episode instead of any episode of Craig of the Creek if kids playing outside is your jam. Only watch Onion Gang if you’re a glutton for punishment.

We’re the one, we’re the ONE! TWO! THREE! FOUR!

Part of me wants to rank this higher than Fusion Cuisine and House Guest, where I find more insulting mischaracterizations. But both of those episodes have enjoyable elements that are weighed down by lousy depictions of Connie and Greg; Garnet’s a riot in the former, and there’s a sweet song in the latter despite being muddled by context. Whereas there are no real bright spots in Onion Gang. It’s an unbearable eleven minutes that I’m never going to watch again.

Sadie’s Song is worse because it’s the worst Steven episode in the series and it misses the mark so much, and it’s important to Sadie’s arc so it’s harder to skip, which makes me resent it more. Island Adventure is worse because its moral is that abuse is a reasonable method of communication. But that’s all that’s stopping Onion Gang from reaching the very bottom.

The good news is that this is it for my No Thanks list, and while I might’ve had a bit of fun dissecting why I dislike Onion Gang so much, it bears saying that 6 stinkers in 180 episodes and a movie ain’t shabby.

Top Twenty

Steven and the Stevens

Hit the Diamond

Mirror Gem

Lion 3: Straight to Video

Alone Together

Last One Out of Beach City

The Return

Jailbreak

The Answer

Mindful Education

Sworn to the Sword

Rose’s Scabbard

Earthlings

Mr. Greg

Coach Steven

Giant Woman

Beach City Drift

Winter Forecast

Bismuth

When It Rains

Love ‘em

Laser Light Cannon

Bubble Buddies

Tiger Millionaire

Lion 2: The Movie

Rose’s Room

An Indirect Kiss

Ocean Gem

Space Race

Garnet’s Universe

Warp Tour

The Test

Future Vision

On the Run

Maximum Capacity

Marble Madness

Political Power

Full Disclosure

Joy Ride

Keeping It Together

We Need to Talk

Chille Tid

Cry for Help

Keystone Motel

Catch and Release

Back to the Barn

Steven’s Birthday

It Could’ve Been Great

Message Received

Log Date 7 15 2

Same Old World

The New Lars

Monster Reunion

Alone at Sea

Crack the Whip

Beta

Back to the Moon

Kindergarten Kid

Buddy’s Book

Like ‘em

Gem Glow

Frybo

Arcade Mania

So Many Birthdays

Lars and the Cool Kids

Onion Trade

Steven the Sword Fighter

Beach Party

Monster Buddies

Keep Beach City Weird

Watermelon Steven

The Message

Open Book

Story for Steven

Shirt Club

Love Letters

Reformed

Rising Tides, Crashing Tides

Onion Friend

Historical Friction

Friend Ship

Nightmare Hospital

Too Far

Barn Mates

Steven Floats

Drop Beat Dad

Too Short to Ride

Restaurant Wars

Kiki’s Pizza Delivery Service

Greg the Babysitter

Gem Hunt

Steven vs. Amethyst

Bubbled

Enh

Cheeseburger Backpack

Together Breakfast

Cat Fingers

Serious Steven

Steven’s Lion

Joking Victim

Secret Team

Say Uncle

Super Watermelon Island

Gem Drill

Know Your Fusion

Future Boy Zoltron

No Thanks!

6. Horror Club 5. Fusion Cuisine 4. House Guest 3. Onion Gang 2. Sadie’s Song 1. Island Adventure

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conversation with David Panos about The Searchers

The Searchers by David Panos is at Hollybush Gardens, 1-2 Warner Yard London EC1R 5EY, 12 January – 9 February 2019

There is something chattering. Alongside a triptych a small screen displays the rhythmic loop of hands typing, contorting, touching, holding. A movement in which the artifice strains between shuddering and juddering. Machinic GIFs seem to frame an event which may or may not have taken place. Their motions appear to combine an endless neurotic repetition and a totally adrenal pumped and pumping tension, anticipating confrontation.

JBR: How do the heavily stylised triptych of screens in ‘The Searchers’ relate to the GIF-like loops created out of conventionally-shot street footage? DP: I think of the three screens as something like the ‘unconscious’ of these nervous gestures. I’m interested in how video compositing can conjure up impossible or interior spaces, perhaps in a way similar to painting. Perhaps these semi-abstract images can somehow evoke how bodies are shot through with subterranean currents—the strange world of exchange and desire that lies under the surface of reality or physical experience. Of course abstractions don't really ‘inhabit’ bodies and you can’t depict metaphysics, but Paul Klee had this idea about an aesthetic ‘interworld’, that painting could somehow reveal invisible aspects of reality through poetic distortion. Digital video and especially 3D graphics tend to be the opposite of painting—highly regimented and sat within a very preset Euclidean space. I guess I’ve been trying to wrestle with how these programs can be misused to produce interesting images—how images of figures can be abstracted by them but retain some of their twitchy aliveness. JBR: This raises a question about the difference between the control of your media and the situation of total control in contemporary cinematic image making. DP: Under the new regimes of video making, the software often feels like it controls you. Early analogue video art was a sensuous space of flows and currents, and artists like the Vasulkas were able to build their own video cameras and mixers to allow them to create whole new images—in effect new ways of seeing. Today that kind of utopian or avant-garde idea that video can make surprising new orders of images is dead—it’s almost impossible for artists to open up a complex program like Cinema 4D and make it do something else. Those softwares were produced through huge capital investment funding hundreds of developers. But I’m still interested in engaging with digital and 3D video, trying to wrestle with it to try and get it to do something interesting—I guess because the way that it pictures the world says something about the world at the moment—and somehow it feels that one needs to work in relation to the heightened state of commodification and abstraction these programs represent. So I try and misuse the software or do things by hand as much as possible, and rather than programming and rendering I manipulate things in real time. JBR: So in some way the collective and divided labour that goes into producing the latest cinematic commodities also has a doubled effect: firstly technique is revealed as the opposite of some kind of freedom, and at the same time this has an effect both on how the cinematic object is treated and how it appears. To be represented objects have to be surrounded by the new 3D capture technology, and at the same time it laminates the images in a reflected glossiness that bespeaks both the technology and the disappearance of the labour that has gone into creating it. DP: I’m definitely interested in the images produced by the newest image technologies—especially as they go beyond lens-based capture. One of the screens in the triptych uses volumetric capturing— basically 3D scanning for moving image. The ‘camera’ perspective we experience as the viewer is non-existent, and as we travel into these virtual, impossible perspectives it creates the effect of these hollowed out, corroded bodies. This connects to a recurring motif of ‘hollowing out’ that appears in the video and sculpture I’ve been making recently. And I have a recurring obsession with the hollowing out of reality caused by the new regime of commodities whose production has become cut to the bone, so emptied of their material integrity that they’re almost just symbols of themselves. So in my show ‘The Dark Pool’ (Hollybush Gardens, 2014) I made sculptural assemblages with Ikea tables and shelves, which when you cut them open are hollow and papery. Or in ‘Time Crystals’ (Pumphouse Gallery, 2017) I worked with clothes made in the image of the past from Primark and H&M that are so low-grade that they can barely stand washing. We are increasingly surrounded by objects, all of which have—through contemporary processes of hyper-rationalisation and production—been slowly emptied of material quality. Yet they have the resemblance of luxury or historical goods. This is a real kind of spectral reality we inhabit. I wonder to myself about how the unconscious might haunt us in these days when commodities have become hollow. Might it be like Benjamin’s notion of the optical unconscious, in which through the photographic still the everyday is brought into a new focus, not in order to see what is behind the veil of semblance, but to see—and reclaim for art—the veiling in a newly-won clarity. DP: Yes, I see these new technologies as similar, but am interested in how they don't just change impact perception but also movement. The veiled moving figures in ‘The Searchers' are a strange byproduct of digital video compositing. I was looking to produce highly abstract linear depictions of bodies reduced to fleshy lines, similar to those in the show and I discovered that the best way to create these abstract images was to cover the face and hands of performers when you film them to hide the obvious silhouettes of hands and faces. But asking performers to do this inadvertently produced a very peculiar movement—the strange veiled choreography that you see in the show. I found this footage of the covered performers (which was supposed to be a stepping stone to a more digitally mediated image, and never actually seen) really suggestive— the dancers seem to be seeking out different temporary forms and they have a curious classical or religious quality or sometimes evoke a contemporary state of emergency. Or they just look like absurd ghosts. JBR: In the last hundred years, when people have talked about ghosts the one thing they don’t want to think about is how children consider ghosts, as figures covered in a white sheet, in a stupid tangible way. Ghosts—as traumatic memories—have become more serious and less playful. Ghosts mean dwelling on the unfinished business of the past, or apprehending some shard of history left unredeemed that now revisits us. Not only has no one been allowed to be a child with regard to ghosts, but also ghosts are not for materialists either. All the white sheets are banished. One of the things about Marx when he talks about phantoms—or at least phantasmagorias—is much closer to thinking about, well, pieces of linen and how you clothe someone, and what happens with a coat worked up out of once living, now dead labour that seems more animate than the human who wears it. DP: Yes, I’ve been very interested in Marx’s phantasmagorias. I reprinted Keston Sutherland’s brilliant essay on how Marx uses the term ‘Gallerte’ or ‘gelatine’ to describe abstract labour for a recent show. Sutherland highlights a vitalism in Marx’s metaphysics that I’m very drawn to. For the last few years I’ve been working primarily with dancers and physical performers and trying to somehow make work about the weird fleshy world of objects and how they’re shot through with frozen labour. I love how he describes the ‘wooden brain’ of the table as commodity and how he describes it ‘dancing’—I always wanted to make an animatronic dancing table. JBR: There is also a sort of joyfulness about that. The phantasmagoria isn’t just scary but childish. Of course you are haunted by commodities, of course they are terrifying, of course they are worked up out of the suffering and collective labour of a billion bodies working both in concert and yet alienated from each other. People’s worked up death is made into value, and they all have unfinished business. But commodities are also funny and they bumble around; you find them in your house and play with them. DP: Well my last body of work was all about dancing and how fashion commodities are bound up with joy and memory, but this show has come out much bleaker. It’s about how bodies are searching out something else in a time of crisis. It’s ended up reflecting a sense of lack and longing and general feeling of anxiety in the air. That said I am always drawn to images that are quite bright, colourful and ‘pop’ and maybe a bit banal—everyday moments of dead time and secret gestures. JBR: Yes, but they are not so banal. In dealing with tangible everyday things we are close to time and motion studies, but not just in terms of the stupid questions they ask of how people work efficiently. Rather this raises questions of what sort of material should be used so that something slips or doesn’t slip—or how things move with each other or against each other—what we end up doing with our bodies or what we end up putting on our bodies. Your view into this is very sympathetic: much art dealing in cut-up bodies appears more violent, whereas the ruins of your abstractions in the stylised triptych seem almost caring. DP: Well I’m glad you say that. Although this show is quite dark I also have a bit of a problem with a strain of nihilist melancholy that pervades a lot of art at the moment. It gives off a sense of being subsumed by capitalism and modern technology and seeing no way out. I hope my work always has a certain tension or energy that points to another possible world. But I’m not interested in making academic statements with the work about theory or politics. I want it to gesture in a much more intuitive, rhythmic, formal way like music. I had always made music and a few years back started to realise that I needed to make video with the same sense of formal freedom. The big change in my practice was to move from making images using cinematic language to working with simultaneous registers of images on multiple screens that produce rhythmic or affective structures and can propose without text or language. JBR: The presentation of these works relies on an intervention into the time of the video. If there is a haunting here its power appears in the doubled domain of repetition, which points both backwards towards a past that must be compulsively revisited, and forwards in convulsive anticipatory energy. The presentation of the show troubles cinematic time, in which not only is linear time replaced by cycles, but also new types of simultaneity within the cinematic reality can be established between loops of different velocities. DP: Film theorists talk about the way ‘post-cinematic’ contemporary blockbusters are made from images knitted together out of a mixture of live action, green-screen work, and 3D animation. I’ve been thinking how my recent work tries to explode that—keep each element separate but simultaneous. So I use ‘live’ images, green-screened compositing and CGI across a show but never brought together into a naturalised image—sort of like a Brechtian approach to post-cinema. The show is somehow an exploded frame of a contemporary film with each layer somehow indicating different levels of lived abstractions, each abstraction peeling back the surface further. JBR: This raises crucial questions of order, and the notion that abstraction is something that ‘comes after’ reality, or is applied to reality, rather than being primary to its production. DP: Yes good point. I think that’s why I’m interested in multiple screens visible simultaneously. The linear time of conventional editing is always about unveiling whereas in the show everything is available at the same time on the same level to some extent. This kind of multi-screen, multi-layered approach to me is an attempt at contemporary ‘realism’ in our times of high abstraction. That said it’s strange to me that so many artworks and games using CGI these days end up echoing a kind of ‘naturalist’ realist pictorialism from the early 19th Century—because that’s what is given in the software engines and in the gaming-post-cinema complex they’re trying to reference. Everything is perfectly in perspective and figures and landscapes are designed to be at least pseudo ‘realistic’. I guess that’s why you hear people talking about the digital sublime or see art that explores the Romanticism of these ‘gaming’ images. JBR: But the effort to make a naturalistic picture is—as it was in the 19th century—already not the same as realism. Realism should never just mean realistic representation, but instead the incursion of reality into the work. For the realists of the mid-19th century that meant a preoccupation with motivations and material forces. But today it is even more clear that any type of naturalism in the work can only serve to mask similar preoccupations, allowing work to screen itself off from reality. DP: In terms of an anti-naturalism I’m also interested in the pictorial space of medieval painting that breaks the laws of perspective or post-war painting that hovered between figuration and abstraction. I recently returned to Francis Bacon who I was the first artist I was into when I was a teenage goth and who I’d written off as an adolescent obsession. But revisiting Bacon I realised that my work is highly influenced by him, and reflects the same desire to capture human energy in a concentrated, abstracted way. I want to use ‘cold’ digital abstraction to create a heightened sense of the physical but not in the same way as motion capture which always seems to smooth off and denature movement. So the graph-like image in the centre of the triptych (Les Fantômes) in this show twitches with the physicality of a human body in a very subtle but palpable way. It looks like CGI but isn’t and has this concentrated human life force rippling through it.

If in this space and time of loops of the exploded unstill still, we find ourselves again stuck in this shuddering and juddering, I can’t help but ask what its gesture really is. How does the past it holds gesture towards the future? And what does this mean for our reality and interventions into it. JBR: The green-screen video is very cold. The ruined 3D version is very tender. DP: That's funny you say that. People always associate ‘dirty’ or ‘poor’ images with warmth and find my green-screen images very cold. But in the green-screened video these bodies are performing a very tender dance—searching out each other, trying to connect, but also trying to become objects, or having to constantly reconfigure themselves and never settling. JBR: And yet with this you have a certain conceit built into the drapes you use: one that is in a totally reflective drape, and one in a drape that is slightly too close to the colour of the greenscreen background. Even within these thin props there seems to be something like a psychological description or diagnosis. And as much as there is an attempt to conjoin two bodies in a mutual darkness, each seems thrown back by its own especially modern stigma. The two figures seem to portray the incompatibility of the two poles established by veiled forms of the world of commodities: one is hidden by a veil that only reflects back to the viewer, disappearing behind what can only be the viewer’s own narcissism and their gratification in themselves, which they have mistaken for interest in an object or a person, while the other clumsily shows itself at the very moment that it might want to seem camouflaged against a background that is already designed to disappear. It forces you to recognise the object or person that seems to want to become inconspicuous. And stashed in that incompatibility of how we find ourselves cloaked or clothed is a certain unhappiness. This is not a happy show. Or at least it is a gesturally unsettled and unsettling one. DP: I was consciously thinking of the theories of gesture that emerged during the crisis years of the early 20th century. The impact of the economic and political on bodies. And I wanted the work to reflect this sense of crisis. But a lot of the melancholy in the show is personal. It's been a hard year. But to be honest I’m not that aligned to those who feel that the current moment is the worst of all possible times. There’s a left/liberal hysteria about the current moment (perhaps the same hysteria that is fuelling the rise of right-wing populist ideas) that somehow nothing could be worse than now, that everything is simply terrible. But I feel that this moment is a moment of contestation, which is tough but at least means having arguments about the way the world should be, which seems better than the strange technocratic slumber of the past 25 years. Austerity has been horrifying and I realise that I’ve been relatively shielded from its effects, but the sight of the post-political elites being ejected from the stage of history is hopeful to me, and people seem to forget that the feeling of the rise of the right has been also met with a much broader audience for the left or more left-wing ideas than have been previously allowed to impact public discussion. That said, I do think we’re experiencing the dog-end of a long-term economic decline and this sense of emptying out is producing phantasms and horrors and creating a sense of palpable dread. I started to feel that the images I was making for ‘The Searchers’ engaged with this. David Panos (b. 1971 in Athens, Greece) lives and works in London, UK. A selection of solo and group exhibitions include Pumphouse Gallery, Wandsworth, London, 2017 (solo); Sculpture on Screen. The Very Impress of the Object, Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon, Portugal [Kirschner & Panos], 2017; Nemocentric, Charim Galerie, Vienna, 2016; Atlas [De Las Ruinas] De Europa, Centro Centro, Madrid, 2016; The Dark Pool, Albert Baronian, Brussels, (solo), 2015; The Dark Pool, Galeria Marta Cervera, Madrid, 2015; Whose Subject Am I?, Kunstverein Fur Die Rheinlande Und Westfalen, Düsseldorf, 2015; The Dark Pool, Hollybush Gardens, London, (solo), 2014; A Machine Needs Instructions as a Garden Needs Discipline, MARCO Vigo, 2014; Ultimate Substance, B3 Biennale des bewegten Blides, Nassauischer Kunstverein, Wiesbaden, (Kirschner & Panos solo), 2013; Ultimate Substance, CentrePasquArt, Biel, (Kirschner & Panos solo), 2013; Ultimate Substance, Extra City, Antwerp, (Kirschner & Panos solo), 2013; The Magic of the State, Lisson Gallery, London, 2013; HELL AS, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2013.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brooklyn Nine-Nine’s Final Season is a Bit of a Letdown

https://ift.tt/3n1Ra7e

This article contains spoilers for Brooklyn Nine-Nine season 8 episodes 7 and 8.

The uneven final season of Brooklyn Nine-Nine continues this week with two episodes that feel like by-the-numbers installments that do little to dramatically improve the feeling that Season 8 has been a disappointment. By trying to serve two masters — responsibly telling stories about policing in a post-George Floyd world while also telling silly detective stories — Brooklyn Nine-Nine has given viewers tonal whiplash.

The dramatic moments don’t quite land and can feel heavy-handed, while the laughs simply have been few and far between. While “Game of Boyles” and “Renewal” each have their moments, with “Renewal” neatly, if too quickly, tying up the season’s arc, the entire affair feels rushed and half-hearted. And “half-hearted” has never been a word to describe the series before.

“Game of Boyles” is first and serves as a pseudo-parody of Knives Out. The problem here is that by this point, the film is almost two years old, and the parody feels stale. Also feeling stale are the Boyle family jokes. Look, I’ve always been a mark for Boyle jokes, like the weird unintentional sexual innuendos and the beige outfits, and while “Game of Boyles” gets laughs out of one Boyle calling a head massage an “HJ” and their affinity for drinking nutria milk, by the end of the episode, it all starts to feel repetitive.

The plot centers on the death of Charles’ great Uncle Pappy. Trying to escape the demands of fatherhood and support their friend, Jake and Terry accompany Charles to the Boyle family farm, but they discover that something is amiss with Pappy’s death. This leads to a classic whodunit in the mold of Rian Johnson’s film, complete with conflicting flashbacks and witness testimonies from strange Boyles. The Boyle black sheep Lyndon is suspected of killing his father, and once a suspicious hair is found near some rat poison, Jake decides to DNA test each Boyle to determine who it belongs to.

In a classic twist, it turns out that the hair belonged to a nutria who got into the poison, and since Pappy naturally drank the nutria’s milk, he succumbed to its effects. But that’s not the twist; the real twist is that the DNA test reveals that Charles is not actually a Boyle. While Charles resembles the Boyle family because the Boyle family cuddles their children so hard it reshapes their bones (the episode’s best joke), he’s not a true Boyle.

This reveal was engineered by Charles’ jealous cousin, Sam, but it’s beside the point. It all sends Charles into an identity crisis, but it’s quickly overcome when Charles miraculously opens his family’s Grandmother Starter, an extremely old sourdough starter with a very tight lid. The family says whoever opens the jar is said to be the One True Boyle, so Boyle’s crisis is over before it really has a chance to get going. Perhaps if this came earlier in the episode, the writers could have made more of a meal out of a spiraling Charles, but this resolves itself far too simply.

Same with the B-plot, which finds Holt getting on a dating app at the behest of Rosa and Amy. The pair believe that if Holt gets on a dating app, he’ll see how dreadful the waters are and try harder to resolve things with Kevin. Holt suspects the pair are trying to manipulate him, so he pretends to be into the dating scene, but his behavior in trying to “beat” Rosa and Amy allows him to see that he’s been trying to defeat Kevin in their therapy sessions. At the episode end, Kevin and Holt reunite in a pure Nancy Meyers movie moment, but once again, it all feels a bit rushed. There are some solid dating app jokes lobbied, but nothing especially memorable. Overall “Game of Boyles” is a serviceable if unspectacular episode.

Read more

TV

Brooklyn Nine-Nine Bungles The Pontiac Bandit’s Last Appearance

By Nick Harley

TV

Brooklyn Nine-Nine Season 8 Takes On The “Blue Flu”

By Nick Harley

If “Game of Boyles” was more parody than classic BK99, “Renewal” is the show hitting all of its familiar beats. There’s Jake and Holt donning disguises, racing against the clock to solve a case while the rest of the team pair off to aid in their main mission. In this case, Holt and Jake are trying to retrieve O’Sullivan’s laptop after he fudged the CompStat numbers on their police reform proposal.

They must distract O’Sullivan’s mom and break into his Man Cave to steal the laptop while Amy and Terry retrieve a fingerprint from O’Sullivan. What makes all of this trickier is that it’s happening on the day that Holt and Kevin have chosen to renew their vows in a lavish ceremony. Since Holt’s dedication to work is already their main point of conflict, Boyle and Rosa must distract Kevin so he doesn’t find out that Holt is working on their special day.

There are a lot of solid jokes in the episode. Rosa’s war with cheddar, Holt doing a callback to his classic “Bone?!” outrage, and Jake’s escalating bad investments are all solid gags. There’s even a funny bit where Holt repeatedly uses the name of a fake porno to get out of trouble, but the funny gags are offset by hamfisted “serious” moments.

The Kevin-Holt marital problems simply do not feel high-stakes enough, nor in actual jeopardy, to warrant so much attention this season. While their coupling has provided great B-plot material, it simply buckles under the weight of trying to carry the main plot. Compare and contrast Amy and Jakes wedding to the ceremony between Holt and Kevin here, and you’ll quickly realize that the latter doesn’t have the same emotional heft.

That said, it was nice to finally see the couple kiss in two back-to-back episodes after never really giving the couple intimate moments, and Marc Evan Jackson really does his best to sell both moments. Andre Braugher, as always, is a revelation.

Anyway, this episode also falters by introducing the idea of Holt retiring for about 15 minutes before rolling it back entirely. Surely this could have continued to drive some drama in the final two episodes, but the idea of Holt retiring is never given enough time to feel like a real concern. Finally, after the plan to save their police reform proposal works, everyone tries to act like policing in NYC has been solved. Holt manages to say something like “this isn’t guaranteed to solve everything” but the episode acts as if this is a magic cure-all, which feels insanely naïve compared to the premiere episode’s bleak, thorough explanation about why cops are rarely prosecuted.

Comparing the end of this episode to the dark reality of the first feels like you’re watching two completely different shows. It’s understandable that a sitcom might want to have the sunny side ending, but this opens up the issue of whether this show was ever the appropriate place to be having these conversations in the first place. It’s yet another example of how this season of Brooklyn Nine-Nine just cannot please both sides of its audience.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

With just one super-sized episode remaining, season 8 of Brooklyn Nine-Nine has been a serious mixed bag that will need to do a lot to pull off a satisfying conclusion. With Amy promoted to chief, it feels like Jake and Amy trying to navigate a work-life balance may provide the drama for the final two installments. I’d also expect a plethora of returning guest stars and recurring gags. While Season 8 hasn’t been a complete disaster, I’m really hoping they can stick the landing, or else this eighth and final season is really going to be a letdown.

The post Brooklyn Nine-Nine’s Final Season is a Bit of a Letdown appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3jJJOms

0 notes

Text

Trump acts and talks like a stand-up comic, but the joke is on the American people

At first listen, Donald Trump’s speaking style when he eschews the teleprompter seems chaotically free form, as if he tossed a few dozen tweets and sound bites into one of his “Make America Great Again” caps and picked a few out, one at a time, not bothering to supply connective material or an overarching direction. But there is a method to Trump’s rhetorical madness—a tried and true method that has been around since at least the British music halls of the 19th century.

It’s called stand-up comedy, a style of public speaking with which voters are familiar from late night comedy shows and prime time specials, a style which generally makes its live and broadcast audiences feel good because it makes them laugh, even when the comic is discussing something serious or infuriating. Talking like a stand-up comic may be as significant a part of Trump’s appeal to his core as his nativism, racism, misogyny and isolationism.

Most elected officials and candidates use the same speaking style, which after salutations and a short joke follows a basic three-part structure: 1) Tell them what you’re going to say; 2) Say it; 3) Tell them what you just said. Within that overall framework, the typical political speech will go from issue to issue. In each part of the speech, the speaker will employ a rather limited set of rhetorical devices: using more words than are necessary as opposed to speaking directly; referencing a mix of anecdotes and isolated statistics; and hedging bets with such weaselly phrases as “anticipate” “start to address” and “return to American traditions.” The speaker typically builds tension through repetition, especially of the first few words of a sentence, as exemplified by Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream…” speech. For example, in a speech warning of the danger of electing about Trump that Hillary Clinton made in June 2016, she repeated “He said…” to begin a series of five sentences in a row, and later repeated “It’s no small thing…” to begin three sentences in a row. In a typical stump speech, Bernie Sanders would embed the emphatic rendering of the simple phrase, “we are going to” in four or five sentences in a row.

Except for the use of anecdotes and statistics, both often fabricated, Donald Trump rejects this standard stump speech style in favor of stand-up comedy.

We can identify several characteristics of stand-up comedy that Trump has repurposed for the political arena. First and foremost is the lack of a recognizable formal structure in Trump’s rants. The contemporary comic for the most part doesn’t tell traditional jokes, but rambles from topic to topic, free form and without apparent goal, occasionally telling a story or saying something funny or zinging a sacred cow or well-known human foible. You never have the feeling that the contemporary comic is scripted, but rather speaking a spontaneous stream of consciousness rap. And yet she-he manages always to tell the same jokes and even sling the same insults at audience members in all routines. Doesn’t that sound like Trump? For Trump, the jokes are the insults, the zingers, the boasts, the false facts, the inaccurate characterizations and the unrealistic promises. Instead of starting with the standard “Great to be here,” Trump will often begin in the middle of an anecdote, sometimes even borrowing the “A funny thing happened on my way to the show” joke that begins many classic stand-up comedy routines. For example, the first words of his speech of his victory tour, in North Carolina, were “So the weather was really bad, really bad, and they said, ‘You know these are great people in North Carolina. They won’t mind.’ No, but they said, ‘they won’t mind, sir, if you canceled and made it another time.’ And I said, what?”

The contemporary comic will take a complex social issue, reduce it to one or two points which will be inflammatory but not necessarily salient and then melt away our anxiety with simplistic, often aggressive and senseless exhortations. Lewis Black and Chris Rock both take this approach. Doesn’t it also sound like what Trump has done to many issues, for example, reducing the complexities illegal immigration to building a wall and the fight against terrorism to limiting immigration from Muslim countries?

Stand-up comics frequently find humor in playing on stereotypes or insulting people.

Sarah Silverman, Chris Rock, Ron White, they all reduce people to stereotypes consisting of one or two traits, and then make funny remarks or tell stories that exemplify those traits. It’s what Trump does to issues and to other politicians—“Crooked Hillary,” “Lying Ted, “Little Marco.” While some comedians, such as Don Rickles, Dom Irrera and Lisa Lampanelli, built their routines entirely around insults, most will throw in at least some name-calling, sometimes of the audience, sometimes of well-known people, sometimes of themselves. Insult humor is also a mainstay of situation comedies like “Big Bang Theory,” “Two Broke Girls,” “Everybody Love Raymond” and “Two and a Half Men,” for example.

In stereotyping people, stand-up comics will often briefly leave their own persona by changing their voice and body movements to imitate another person. A wide range of comics will play several parts in their routines, from Bill Cosby to Chris Rock. Seth Meyers, Stephen Colbert and Bill Maher often breaks into their respective versions of Trump’s voice for a sentence or two. A few extremely gifted mimics like Jonathan Winters and Robin Williams have built their entire routines going from character to character. Some of Trump’s most notorious moments occur when he is briefly playing another person, such as his imitation of a reporter with a physical disability. Trump imitated others in the North Carolina speech referenced above. No other politician of recent vintage would dare take on the voice and gestures of another person.

The contemporary comic is self-referential, either drawing from her or his own life or interrupting a thought process to refer to her or himself—how the performance is going, why something makes the performer angry, the effect of current events on the comic’s personal life or something else just as extraneous to the topic at hand. Those who believe that Trump is unqualified for office because of his instability often cite his extreme narcissism as a character flaw. Many of his lies stem from an irrational desire to self-aggrandize. His early speeches after the inauguration, to the Central Intelligence Agency and members of the military, started with and returned often to his personal issues—poll and voting results and insults he may or may not have hurled. There are many comics who focus on themselves, from Jack Benny to Rodney Dangerfield on to Elaine Boosler, Wendy Liebman, Amy Schumer, Lewis Black and Jeff Foxworthy, among myriad others.

Other than talk-show hosts who pretty much deliver jokes in the tradition of Bob Hope, most contemporary stand-up comedians play a comic character that is a well-known stereotype. There are red-neck comedians like Ron White, Bill Engvall and Jeff Foxworthy. Wendy Liebman and Sarah Silverman are promiscuous Jewish-American princesses. Chris Tucker is an angry black man. Amy Schumer is always a party girl. George Lopez plays a series of Hispanic stereotypes and D. J. Hughley and Eddy Murphy play a series of African-American stereotypes. Playing a role is a cherished tradition of stand-up comedy: Jack Benny was a miser. Red Skelton was a clown. Lenny Bruce was a hipster; Cheech and Chong were dopesters. Irwin Corey was a gasbag.

Trump plays a stereotype character whose roots go back to the Italian commedia dell’arte in the Renaissance. But every comic type with origins of a thousand years will have many manifestations. The left, Democrats, many centrists and the mainstream news media see one version of the classic type upon which Trump has modeled, subconsciously or not, his public person. But Trump supporters saw a different version, comic to be sure, but also heroic.

At essence, Trump is Pantalone—the older, wealthy man, often vain, often a lecher, often a bully, often pompous and ignorant, who usually gets his comeuppance in commedia dell’arte skits, sometimes even wearing the horns of a cuckold. Moliere’s “bourgeois gentleman” is the classic example of this comic type. A friendlier, sunnier and definitely de-sexed precursor to Trump was Ted Baxter of the Mary Tyler Moore show, played by Ted Knight.

Most of the intelligentsia across the political spectrum view Trump as the know-nothing buffoon version of Pantalone, the bourgeois gentleman who thinks he knows more than the dancing, speaking, music and other experts he has hired to aggrandize his reputation, or perhaps a Ted Baxter as a sexual predator.

To New Yorkers, Trump has long been a puffed-up and vain buffoon—a wealthy fool, someone with a lot of money but no taste. Before running for president, the properties he built were garish. His private life exemplified what used to be called the “nouveau riche,” those who have money but spend it tastelessly and foolishly. His “Apprentice” TV show was a parody version of the business world, his gruff and insulting style a parody of a type of executive who is not all that prevalent nowadays, certainly not among public companies responsible to shareholders.

But the rich and pampered oaf is not what his followers saw in Trump. To Trump voters, he was the Rodney Dangerfield and Jackie Mason characters of the two Caddyshack movies of the 1980’s that are still frequently aired on a number of broadcast and cable stations. Both play extremely rich white males who made their money at least partially in real estate development. Their vulgarity, apparent ignorance of social etiquette and kind treatment of the “hired help” turn them into average Joes who are breaking down the barriers of elite institutions. Viewers may laugh at Dangerfield and Mason as they commit social faux pas or make ridiculous statements, but we treat them as heroes who upend the social order for the good of the whole when they insult, trick or defeat pompous and snobby rich folk. There is no difference in what the audience feels for these rich disrupters in the Caddyshack movies from what supporters feel about Donald Trump. In the numerous interviews with core Trump supporters since the election, they forgive his vulgarity and stumbling as part and parcel of his outsider status.

How much has Trump’s stand-up comic style contributed to his success in connecting with enough former Democratic voters to win an electoral majority? Did delivering his nativist, racist, misogynist messages like a comic serve to enhance his dystopic ejaculations? It certainly made them seem “funny” to those who despise so-called “political correctness,” but did his voters respond to the jokes positively, or would Trump have won by a greater margin if he had delivered his material in the traditional style that characterized every other candidate on the campaign trail this year?

The very fact that Trump’s language and rhetoric so little resembles the standard fare certainly contributes to the view that he is a disrupter. That he distills his messages into short statements—be they insults, lies or simplifications—make them easy to remember, transmit on social media and use in television news, which now favors quotes of less than ten seconds. His performance might steal a movie satire of elections. On the other hand, the news media treats his rally speeches and early morning tweet rant as manifestations of instability, inexperience and ignorance.

We can’t really know whether his performance helped him win the election unless a progressive Democrat attempts the same approach. I’m certain that any number of Hollywood and New York comedy writers would love to help a candidate of the left try the stand-up style.

Meanwhile, we can anticipate that Trump is going to ramp up campaign style rallies to rile his base as his ratings continue to tumble and he continues to implement unpopular policies and made racist, sexist and otherwise distasteful statements. Like any stand-up comedian, Trump loves the immediate applause, the laughs and the hoots, the love and attention unmediated by polls, computers, experts or media spins. It’s the love of attention that has Trump now actively seeking deals with the Democrats.

Like any professional comic, Trump’s inventiveness feeds off the audience response. Playing to live audiences will therefore likely incite Trump to make more of the type of embarrassing and ignorant statements that marred his campaign and that he has continued to make in the first year of his administration. In the best case scenarios, Trump or others walk back the assertions he makes via Twitter, news conferences and large rallies by twisting the meaning, denying he said it or quietly restating long-standing American policy. We have already seen this dynamic play out again and again—with North Korea, Charlottesville, transgender military service, Israeli settlements and the one China policy. The worst case scenario, as may happen with DACA, has Trump turn a federal department on its head to implement a legally suspect executive order that hurts individuals and the economy, all so that Trump can say he delivers on a promise he makes in his large tent meetings.

In other words, Trump may talk and and act like a stand-up comedian, but the joke is on the American people and the world.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Awakening into his idle state of being came primarily in form of a non-abrupt opening of his eyes, accompanied with a simultaneous, deep inhale. This time around, waking up was nothing like the adrenaline shakiness he would be met with after experiencing multiple REM hours filled with nightmares only. Instead, the return back to consciousness was surprisingly delicate – albeit there was a tremble rendered unavoidable for his silhouette soon thereafter, caused by the cooler-than-room-temperature-but-not-that-cool-at-all night air slipping in by the open balcony door, brushing only moments later through the crevices between where thin pieces of night clothes were semi sticking to hot and sweaty skin. It also wasn’t exactly a terror that perspired his entire body when he was still in the sleeping phase. One could argue it was quite the opposite, even. Paths his brain decided to stray upon when supposedly giving itself rest were namely rather… lascivious, instead. So the explanation behind the tackiness of his tan, glistering in the minimalistic illumination of the outside sources tonight – yellow with Berlin streetlamps and pale white-blue with the bright crescent moon, greens and reds of blinking semaphores, and pinks and oranges of neighbouring apartment complexes – actually lay upon having a lewd dream. Funny thing about that all was, though, that there seemed to be a very thin line between eroticism and the sense of dread sometimes. Because the phenomenon of how fucked up his real life was contrasted all too damn well with how fulfilling and redeeming his dreams were in its stead. So – where non-bad bad dreams should be met with the relief of reality – that’s where the real horror truly began for the dark haired male. Or shortly: who’s to say that this sweet illusion he was having wasn’t nought but a twisted nightmare of a special kind, after all, seeing how its contents were merely wishful thinking targeting an excruciating craving. A craving that brought him to the point where he was left with nothing else to do but to grunt painfully when reaching out to brush at his damp forehead, all whilst moving his body sideways slightly to readjust – only then noticing what he failed to notice in the past few seconds of finally being awake. That is: the truthfully agonizing stiffness between his legs that was most likely bestowed upon him by the fucking Devil himself. The intense manifestation of his delusive longing, throbbing and sore, and most definitely not any longer “just a projection” of what his deepest needs were. A debate could be had whether the world revolving around him at the moment was more vivid or more dull within its grey casted shadows: whether the perception of the dream, in all its velocity and escalation and explosion made the real world seem even more depressing; or if, quite contrary, the cruel existence of right-then-and-there proved to be bizarrely conceivable instead, leaving the fantasy to be an untouched diamond in the rough that dwindled into the night like the occasional honk of a taxi on the streets down below. Truth most likely lay somewhere in between, as it commonly did, but whatever the case might have been, one thing was for sure: the room remained stained with heatwaves that reminded the restless lanky body of a lover’s embrace, and reeked of an unachievable sort of nostalgia. And so he closed his eyes tight again, fists crumpling together at the sheets that weren’t covering him any longer, lost throughout the toss and turn, while his mind was trying to un-think the unthinkable. Crossing his ankles, rubbing his calves, readjusting his knees – he did whatever was physically in his power to just make it go away. But it wouldn’t do that. It simply wouldn’t comply, wouldn’t obey, wouldn’t follow any orders pointed at abandoning its stance. Pressing his thumb to the side of his groin, against the artery, it is with frustration that he groaned, grinding his teeth as he went in to lightly punch at his upper thigh. “Come on,” escaped from him the obvious helplessness, slight tremor in the frustrated tone, a little vibrato against the pillow to which such was muttered in a sort of defeat. To no avail he tried to draw over the images burned in his thoughts with markers of unattractiveness, not being able to concentrate on anything but the sculptured perfection he had the satisfaction of caressing only moments ago in his vision. In vain it was that he attempted to redirect his brain in another direction, tint the hair of the muse in his reverie he was pulling on a few shades darker, and re-arrange the geometry of the anatomy he was devouring with his own arches and corners. Picture perfect and on a constant loop, the projection evolved behind his closed lids, unsynchronised only in the inner conflict of what was his bodily need, and on the other hand, knowing that this shouldn’t be happening. Not any longer, at least. The frames of the traced back scene were branded in his mind, so much so that he could swear he saw the film burning at the sides, as though such was being a metaphor for a headache yet to come, while the prickly flickering of its flames sparked more and more unwanted excitement.

Tom thought of his brother, and he didn’t want to do it. Tom thought of his brother, and that’s also exactly why doing it was unavoidable, as well. Bill wanted things to be different between them. Bill longed for other people. And Tom, well… Tom was lying in his bed, awoken with all the repressed yearning of the months that had passed, immorality spurring from his sunken imagination. To think of it in that way – as immoral, of all things – made his heart feel even heavier, for they were never seen as obscene in his eyes, ever… until lately. Shamelessness was found in the worldly perception of their sin, usually, for both of them, always knowing that they meant something more, realizing they were something otherworldly. But the brunette had never felt like more of a degenerate than right then and there, trying to shut down his body. What made it wrong, perhaps, more than anything else, was in how one-sided it all felt at the given moment. How Bill’s words and doings of recent weeks resonated in the back of his head, all the while the active parts of his brain thrived towards being released, the image of their bodies gliding and rubbing against one another prominent and intrusive. There was nothing he could do, really. To say he was a slave to it sounded so morbidly cliché, but to put it in any other context would be a lie if there ever was any. It was half against his will that he almost roughly pulled on his underwear then, until it was all but pulled down to the extent where he could work with what needed to be carried out. Needed. Rushing, urgent, throbbing; the act wasn’t really one of pleasure. Palm feverishly set in movement, the producer buried his face deeper into the pillow, exhaling shakily against it – glad his hard-on was tended to, but disgusted he had no other way out. His breath tasted stale, of beer and gin, something that might have fallen to attention a bit more was he probably still not a bit drunk from the hours before. The wild fabrication, the nightmare – it was so real, and Tom held onto himself too tightly for it to feel good, almost in a sort of a deranged punishment upon himself for even having the atrocity to pull through such an act. Reaching his ears only, the slickness of repetitive jerks intensified by the second, and with the aching warmth of his lower belly arose in heat also his cheeks. Straying away from the serious mindfulness of his doing, nearing his high by the second, Tom replenished all the bad and filled it up with Bill only. Bill’s lips ghosting upon him, his touch completing him, love exchanged in words and actions… And perhaps that’s why the fall was all the grater, after mere not even three minutes a weak, petty orgasm made him snap from the obsolete deceit of his psyche back to… reality. Life of colour dissolved into nothingness, leaving him with nothing but his ragged breath, and a shaky hand still clasping his messy private parts. He’d hurt himself with the abusing touch, but that was not why his chest heaved more bizarrely, still, only a second later. Tears escaped and the air in his pipe hitched. A “fuck” was spoken out so bizarrely quiet one wouldn’t know it left his mouth at all was one not in his direct proximity. All that was left anymore was the same old insignificance and mind-numbing guilt. And shame and pity. And worthlessness and loneliness. Heavy limbs, heavy everything. And a newfound lusting – one for destruction of some sort. In a mindless explosion, the producer then tosses the pillow from underneath him to the other side of the room, knocking down with it unintentionally the glass from the nightstand, because it’s the closest thing he can do in order to demolish something if that something can’t be himself – but such serves for nothing more than to catch a sight of his lower body better with how he suddenly had to half sit up to do so, causing him to break down in abhorrence for good. The feelings are too substantial to fight against them, and rigidly, Tom’s body slips back into a horizontal state, face hiding away at the expensive sheets down below, staining them with tears and snot and saliva as trembling and silent sobs shake the pathetic, half bared body he had to be the master of. And that’s how he remains. Mindless. Moronic. Number by the second.

1 note

·

View note

Text

#LaraCroft1996 : Quality is better than quantity

I saw the hate messages @positivelyamazonian received and can’t help but find these situations very absurd. I find absurd that we, the fandom of Core Design’s TRs, are often labeled as the haters of the fandom.

What is wrong with hating a video game or a character? People have something they hate or don’t like. And video games / characters are not real people. Don’t you think it’s worse if you went to the personal accounts of other fans and even the developers / employees in order to attack and harass them just because they have opinions you can’t tolerate? Stop taking everything so personal and STOP BEING TOXIC, for God’s sake!

You know, I find it funny when some people place the blame of the franchise’s period of decay before the TR Reboot games happened solely on Core Design. It’s not like the LAU trilogy was a bad copy of the classic TR games where they turned Lara into a annoying character due to her obsession with her mother and the platforming became a lot more easier. Yes, a bad copy, because Crystal Dynamics didn’t bother to offer something innovative to the original formula which would have made it feel a breath of fresh air.

*alright, getting ready to receive agressive messages of sensitive people feeling butthurt because of this post*

It comes to my mind a personal review of Tomb Raider 2013 a Eurogamer reviewer made about that game in his Youtube channel. He claims that he is not a big fan of Tomb Raider, but he loves when the game is just about exploration and feels organic instead of copying Uncharted while doing it worse than that game. He says this series was so important and innovative time ago that it should have introduced something groundbreaking to the formula instead of ‘’following the leader’‘

*Well, he didn’t use those exact words, but he did use the ‘‘follow the leader’‘ expression. This is the video (sorry it’s in Spanish)*

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7_Kf4j8VNyg

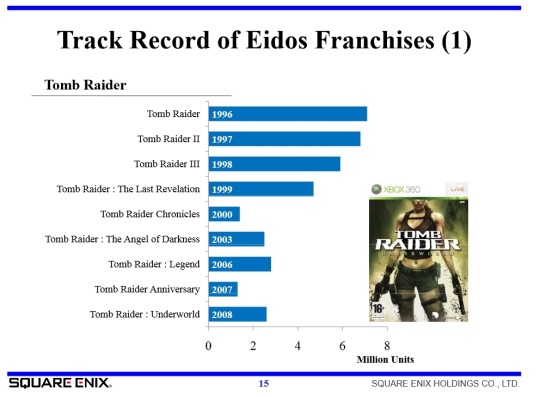

So, back to the point: if you saw the official track record Square Enix released about TR’s sales, you will see the sales decreased after Tomb Raider Legend. Some people will say: ‘’Oh but that just Angel of Darkness’ fault for being a ‘’broken mess’‘ Well, if the Crystal Dynamics’ TR games that came before the Reboot are so superior to the games made by Core Design as some people claim, how do you explain then the decrease in sales? Wouldn’t it be natural if the sales increased instead?

We don’t forget that the one-game-per-year schedule killed Core Design, in fact we, the fans of Core’s Lara, hate that it happened. We also don’t forget that AOD was released in an unfinished state, and it still hurts to some AOD fans who have been dealing with this over 13 years. Was Core partly responsible for the latter problem? Yes, but I personally think Eidos was responsible too, because they forced the release of the game despite the employees told them it was unfinished:

http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2016-10-27-20-years-on-the-tomb-raider-story-told-by-the-people-who-were-there

Why the Reboot games are being so successful when compared to the LAU trilogy? Because they offer something completely new. People were sick of the annual releases and the same formula, and the LAU trilogy only made things a lot worse by offering a very bad clone of the classic games where Lara was sexualized for the first time in-game. They didn’t understand what made the games and the original Lara so special. They just simply didn’t want to, like the people who made the TR movies with Angelina Jodie, where they changed her biography. They were full of prejudice about our Lara, as some interviews done to some of the employees have shown to us.

I have seen people making polls in some forums about which is the best Crystal Dynamics’ TR game made before the Reboot games and in all of them Anniversary won. A remake winning a poll, isn’t it ironic?

And we came to the point I wanted to talk about: Square Enix (and Crystal Dynamics) should be very careful not to exploit the franchise, or else it’ll end like the Core Design games, with people getting sick of the games.

Don’t get me wrong, the current games have a good execution, and I find them to be better than the LAU trilogy. The problem is that they ignore the original formula of exploring tombs and solving puzzles. YES, I know there are tombs in Rise, but they are not the focus most of the time. Most of the time, they are optional and easy to beat. Heck, they even warn you when you are near one of them! Instead, the game focuses more on crafting, combat, stealth, gathering collectibles when exploring the maps, and the RPG elements.

Not to mention that the former writer, Rhianna Pratchett, claims Crystal Dynamics has no plans to bring back the sense of humour and the grey morality the original Lara had:

http://www.rollingstone.com/culture/news/lara-croft-turns-20-why-tomb-raider-gaming-icon-matters-w446693

http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2017-01-17-writing-lara-croft

So it’s clear they want to make their own version of Lara and not to clone her. Sorry guys, but for us if she doesn’t have the same personality as our Lara, she’s not her. The new Lara will NEVER be a replacement, a statement that I think it’s unfair for both the Crystal and Core Design employees. I’m sure she’ll become a professional tomb raider eventually, but she has to have ALL the personality traits to be OUR Lara, including her cold / reserved / loner type attitude. Our Lara was as much relatable as the new Lara. You know what? She cared about other people, too! *BREAKING NEWS* OH MY GOSH, how is that even possible?!

Do you remember when she was determined to fix the big mistake she did in TR The Last Revelation instead of getting angry at her friend Jean-Yves for being sort of scolded by him? Or how she struggled to convince Yarofev to abandon the submarine with her in TR Chronicles? What about the moment when she gave the painting to Eckhart so as to save Kurtis’ life?

‘’The original Lara has no personality, she was a killing machine, yadda, yadda, yadda’’ Don’t make me yawn, please.

Resident Evil 7 took so many years and it paid off, it has sold more than 3 million copies in a few weeks. It has taken inspiration from many horror films in order to offer something new while keeping the original gameplay formula from the old RE games. Why can‘t you give the series a break to bring some important changes, Square Enix? What about a classic TR game with the original Lara made by Naughty Dog and written by Amy Hennig, as their Uncharted series seems to be a spiritual successor to the classic TR games with its light-hearted stories, whereas the new TR games have a serious and gritty tone?

Don’t you think it would give more ideas to the Crystal Dynamics team regarding the direction of their new games?

Why can’t both versions of Lara Croft exist, Square Enix? I think it could be feasible, have you seen the realistic model of classic Lara created by the Deviantart user FredelsStuff? It’s amazing, he’s currently making an AOD version. What about making a Crash Bandicoot-style remaster pack of TR 1 to TR AOD? I suggest you to check the render posted by larafan25 in the following link:

http://www.tombraiderforums.com/showthread.php?t=215932&page=7

In the end, less is more. I would prefer fewer TR games that would keep me intrigued and excited than having an abundance of games that leave me indifferent and with a formula that may sooner or later become repetitive and tiring in the future if it’s not heavily improved.

P.S: I included the hashtag because this was meant to be a letter that addressed Square Enix and I would like if people shared my post. I was making a video and eventually I thought it’d be better to share my thoughts here in Tumblr.

30 notes

·

View notes