#and while she succeeded with unity and destiny

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A/N: Hello again, and with this I think (?) I may have succeeded in writing enough bionicle fic to get it out of my system (unless another plot bunny hits me like a cannonball, but... eh, we'll see) and thus, here is the companion piece to the Vakama & Roodaka oneshot.

This time, exploring the scene where Vakama entered the Great Temple, from his side of things! This was also partially inspired by the scene in Challenge of the Hordika where Nokama is almost physically repulsed in trying to enter the Great Temple :)

x

In the tunnels beneath the temple, Vakama must stoop.

At first he shuffles, mutated arm tucked against him and his sole hand brushing only briefly along the floor to steady himself, but the passages are dark and deep and lined with creatures which seek out the weak. The eyes that watch him are not hungry. They keep their bellies too full for that.

In the end, it is easier quicker to drop to all fours, to share the weight between claw and tool that feet alone cannot. His altered form folds into the new stance with frightening familiarity. It's comfortable.

Natural.

The crown of his mask grazes the tunnel's ceiling, but only in passing. His gait is sure. Well. Surer than the ungainly slouch it had been before.

It was said – back when Matoran were awake to say such things – that even the strongest swimmers of Ga-Metru would hesitate before plunging into the depths of the protodermis sea. Not because the creatures there had any fondness for the taste of Matoran. In truth, it was thought that the rahi actively disliked the flavour. No, it was because the way Matoran swam was indistinguishable from the rahi's usual prey. Only when they had sunk tooth and jaw into their meal would they realise their mistake.

It was an annoying, if harmless mistake for the rahi.

Matoran couldn't say the same.

Vakama's early crawl through the passage had been like that of a Matoran swimmer: functional, but slow and indiscernible from wounded prey. Creatures drag themselves down into these depths to die, in hopes that they will be devoured only when they are too far gone to feel it. The eyes are patient. They will wait to see if this newcomer is similarly inclined.

And so when Vakama drops to his haunches, the eyes blink. Reassess. He moves less like the hunted and more like the hunter now, more predator than prey, and the eyes – and teeth – keep their distance after that.

The path Vakama stalks through was once a protodermis pipe, made obsolete even before the cataclysm. Newer conduits had been built, more efficient, more resilient, and this one had been disconnected but never dismantled. When he reaches its origin, it takes some effort – and his blazer claw – to break the seal across the hatchway, but when he does, one of the temple's protodermis purification chambers looms above him.

The room beyond is quiet.

Unmarked.

He doesn't realise he's stopped until the chittering of his audience draws closer. The snarl he throws back echoes off the pipe's walls, and the eyes retreat, but do not leave.

Vakama curls his hand around the lip of the hatch, and then falters.

Something is wrong.

It's not a pain, because the feeling does not hurt as it ought, but something is undeniably, fundamentally wrong. It causes his breath to catch, his hand to flinch, and it would be so easy, so easy, to turn and walk away, only...

Only he came here for a reason.

The wrongness flares, amplified for a moment, and then he pulls himself up. The eyes watch, but do not follow. Do they feel it too? Can even such base creatures sense the innate malice the temple exudes?

He clambers out of the purification chamber – empty and abandoned now – and stumbles upon his landing. He catches himself, but does not rise back to his feet.

Wrong.

This is wrong.

And at the edge of the wrongness there is a strange sort of terror. It dreads the same way the fire fears the sea, the same way the prey fears the predator; it is the meeting of two primally antithetical forces where only one can survive. It whispers turn back through his mind.

He moves into the next room.

It's one he knows well. Light filters down from the rot-stained windows, centering – as it had the day he'd first seen it – on the suva, and casting long sentinel shadows of the columns standing to attention around it. A crack mars the suva, its stone dome now split cleanly in two from the quakes, and – drawn by some desire he cannot identify (instinct, curiosity... nostalgia?) – he approaches.

It seems so small now. Even bowed and altered in his Hordika form, he looms over the Ta-Metru symbol he'd once had to stretch to reach.

Unbidden, his hand moves to the niche where once he'd placed a Toa Stone – where once he had though himself chosen, duty-bound, destiny-gifted – and falters a breath from the stone.

The wrongness spikes.

Screams.

And with a twist of something he will not call horror, he understands it is not originating from himself.

But from the temple.

It is repulsion. It's alienation. It's recognising him, but as other, as rahi.

It's disgust that a monster would dare enter its sanctuary.

In the Ta-Metru carving, stone once polished to the point of fragmented reflection, he sees a glimmer of his own face. Neither Toa nor Matoran. Nothing blessed by Mata Nui.

Vakama recoils.

And then a wave of his own disgust, propelled by that fury that runs so close to the surface now, rolls through him. If you didn't want us as the Toa, you should've stopped Makuta from choosing us, he thinks, and digs his claws into the stonework.

The wrongness sings.

But he knows it for what it is now, and his morphed, clawed hand gorges scars through the carving. The stone is soft. Its makers had never imagined someone would take a blade to it.

There comes a tapping from across the room, echoing brazenly off the ancient stone walls, and Vakama retreats instinctively into the shadows. A Rahaga enters.

Norik?

No, this Rahaga's armour is more akin to a Po-Matoran than a Ta-Matoran's, the colour of dust and stone. Vakama tries to recall the Rahaga's name – and then dismisses the attempt.

It won't matter, in the end.

The Rahaga walks as he always has, stooped and slow, but clearly unhindered by the temple. He passes by the suva and runs one gnarled hand across the stonework, his movements marred by curiosity rather than reverence.

The rage arrives a fully-formed creation. It drowns out the wrongness, floods the apprehension, and he is moving before he's decided that this is the path he wants.

It is not pain, for it does not hurt as it ought.

But it does still hurt.

x

Whatever the Rahaga might once have been, they are old and weak now. Four are captured before Vakama's rage has a chance to cool, but the ire is no less dangerous when it does.

(That's the thing about Ta-Metru; it's not a place of fire so much as it is of magma. And magma doesn't extinguish with the cold; it sets. It moors itself into place, an unmovable, burning force.)

The rage settles, solidifies around his heart and lungs and carves a home between his breaths.

(Magma is not fire. It does not leap blindly from one source to the next. Instead it advances. Slowly. Steadily. It finds a channel, a destination, and it engulfs all in its path until it reaches it.)

He finds the last two remaining Rahaga, pathetically ignorant to their brothers' fates and still scavenging the temple for answers. He hears the way Norik appraises his sister's translation, relief clear in his voice that they are one step further on this wild rahi chase. Relief, surely, that the Rahaga are one step closer to regaining their Toa form.

(And Vakama's anger has found its destination.)

He does not descend on the Rahaga's leader the way he has the others. No. Norik will know what's coming for him first. He gets to fear. Vakama waits until Gaaki has gone, until Norik is alone, and then he circles. The wrongness thrums in his veins, weighing him down and labouring his breaths. It doesn't matter. Let Norik hear his approach.

Norik doesn't try to run. Vakama will give him that much. (A wise choice. Vakama intends for this encounter to last, but if Norik runs, Vakama cannot be sure he won't chase.) Instead, the malformed once-Toa calls out and actually tries to approach him. Stupid. Doesn't he know that he won't win any fight, transformed as he is? As both of them are? No, instead, he tries to talk. As if they are equals, as if Norik has done anything to deserve his respect rather than his scorn. As if he has earned the temple's forgiveness for his trespassing.

Even when Vakama raises the fate of Norik's fellow Rahaga, Norik attempts to sway him with the illusion of reason, talking of duty and unity, as if he's not using the other Toa Hordika to chase after a rahi myth for his own desires. As if their roles are in any way comparable, both Toa of Fire once, both leaders, it's true, but Vakama hasn't forgone his duty to chase after selfish needs.

And it stops now.

Vakama circles closer, and Norik is still talking, unease in his voice, but not fear. Still searching for the right words to turn Vakama to his bidding as he has the other Toa Hordika. Ever the voice of two-faced logic.

Why won't he just shut up?

Does Norik think him to be as gullible as the others? As quick to desert his duty as them?

And Vakama knows he wants – needs – to shake that assurance, that arrogance out of Norik. Needs to see that facade of self-righteous wisdom crumble into the terror of his situation.

The growl begins deep in his chest and, unleashed, it becomes a roar. He rears out of the darkness, into the weak sphere of light surrounding Norik – and there, there he finally sees true fear fill the old fool's eyes.

Something slams into Vakama and he reels, his roar cut short. His hand reaches automatically, defensively, to his mask. He finds only water there. It clings to him, imbued with some sort of power – he can feel something other in it – but otherwise impotent.

"Leave my brother alone," Gaaki snarls. She stands in the doorway, small and hopelessly overpowered, but her shoulders are tensed with a stubborness Vakama recognises. Already, her spinner is powering up for another shot.

Well. Two can play at that game.

Vakama's rhotuka fires into motion, but the water has seeped into the mechanism, and dowses the fire before it has a chance to catch. He gives it a withering look, before turning the expression onto Gaaki. "Very clever."

Another water spinner hits him, but this time he is braced for it and all it does is wash harmlessly off him.

"Is that all you have?" he asks. His blazer claw splutters, but the claws on his hand flex. After all, there's more than one way to defang a muaka...

Gaaki steps back. Good. She knows she's outmatched. "It's a devastating attack underwater," she offers, and her words are strong but there is a cracked edge to them.

"Then you'd better start finding a puddle," Vakama growls, "before my claws find you," and he drops into a run, feet pounding and fangs bared and that ever-present wrongness humming about him.

She doesn't flee. Just like Norik, she stands her ground, gnarled fingers wrapped tight around her staff. Her eyes are hard, but he sees the way her hands shake.

How long will her resolve last, Vakama wonders. Before or after the claws find their mark?

He never finds out.

He's knocked off his feet before he reaches her, and when he hits the ground, ropes of energy pin him to the earth, like a water-bound rahi caught in a net.

What–

Norik.

He'd forgotten Norik.

He thrashes against the restraints, but they hold strong – for now. His blazer claw splutters again, but it does nothing to the energy that binds him.

He stills as he hears footsteps approach.

The two Rahaga hobble into his line of sight. Gaaki is breathing hard, as if only now is she allowing herself to feel the fear. "You left that late, Norik," she says, and even the breath that follows sounds more like a shaken wheeze than a nervous laugh. "Almost too late."

"I only had the one shot. I couldn't afford to miss," Norik replies. "He's got our brothers. Gaaki, go find–"

"I'm not leaving you alone with him," she retorts. "I only went for a moment before, and look what would have happened if I hadn't returned."

Vakama tilts his head as well as the energy net will allow. He grins at the Rahaga, anger curdling it into a sneer. "Yes, Gaaki, you're very good bait, congratulations." He shifts his gaze to Norik. "But you've always been so good at getting others to do your dirty work, haven't you, Norik?"

Norik doesn't even have the decency of guilt. Instead, he simply looks tired. "Whatever you think you know–"

"I know the truth! You don't care about the Matoran, you only care about yourselves!" He strains against the ropes, and although they do not break, there's a little more give in them than before. He slumps back to the ground, breathing hard. "You might have the other Toa fooled. You might even have the temple fooled, but not me," he growls, and the temple's hatred presses down on him, straining his last words.

Gaaki places a frail hand on her brother's arm. "Norik," she says, and there is such unbearable sorrow in her voice. "He looks in pain."

"It's not my doing," Norik assures her softly. "My snare spinner only binds."

Vakama snarls. "I don't need pity from the likes of you. I know what you are."

"We're allies, Vakama," Norik says, in that insufferably reasonable way of his. "Friends."

"You're frauds," Vakama snaps. He twists against his restraints. They slacken, just a touch. "Liars. You don't deserve to walk these floors."

And the Rahaga stand there, unburdened by the temple's hate, strangers to this land, to Metru Nui, and yet it is Vakama the temple repulses? After everything he has forgone, the life he's abandoned, the friendships he's lost, Mata Nui punishes him?

His rhotuka fires off a fire spinner, and it goes wide, cracks a wall. Norik and Gaaki stumble back, Norik preparing another snare shot, but the energy net holding Vakama snaps. Vakama lurches forward, suddenly free, and slams into Norik.

The snare spinner wraps itself around a column. It lights up the room with crackling energy.

A blast of water grazes past his shoulder, too shy of hitting Norik to commit to taking the easy shot, and Vakama reels towards Gaaki. He fires with a snarl, but hears the snare spinner coming again and ducks at the last moment.

Again his own attack misses and the shot cleaves clean through a wall. Something on the other side begins to smoulder.

Then it begins to rumble.

It's a low sound at first, as deep as the earth and just as vast. Almost like a distant growl. But then the cracks begin to spiral out across the roof, along the columns, and the room buckles.

The light flickers. The frames of the high windows above collapse.

The world becomes fragmented, filled with flickering images. Falling masonry and toppling pillars and dust – but the sounds never relent. Even in the depths of the passing darkness, the thunder continues.

And when the dust settles, so does an awful silence.

Vakama straightens, or does his best approximation of it. Fragments of cracked protodermis fall from his shoulders, his head, his back. He withdraws the hand which has somehow found itself raised above Gaaki, knocking aside the stone slab caught against his arm.

Where's Norik?

Both Hordika and Rahaga stand side by side, that quietness disturbed only by the skittering of stone shards settling. There is wrongness in his breath, his head, and it's impossible to separate where the temple's ends and his begins. But any moment now, Norik will reappear from the wreckage, bearing that ever-same holier-than-thou look, and the anger will rise anew in Vakama.

Any.

Moment.

Now.

"You've killed him," Gaaki says, and her voice breaks that terrible stillness. She draws in a half-breath that cracks into a sob. "You've... oh, Norik..."

No.

No, it was an accident. He hadn't meant to– Norik had simply been in the wrong place. It wasn't as if he'd taken a blazer claw to Norik, or hit him directly with a fire spinner. He'd only meant to... what? What had he only meant to do?

Something swings towards him and he grabs the staff before he even registers what it is.

"He's not dead," Vakama says, and maybe if he says it, he might even believe it. He snaps his gaze to Gaaki, as if her grief is bringing it to pass. "He's not. He's not as easy to kill as that. When the others– when the Toa find him, he'll be fine. Fools like him always find a way to survive."

Gaaki attempts to pull her staff free, but her strength is no match for Vakama's. He wretches it out of her grasp and tosses it aside.

"Stop that."

She doesn't listen to him, only steps back and charges up her rhotuka. The grief in her eyes fogs into hatred.

The water spinner hits him but does little more than rock him.

"Stop."

Gaaki screams, a sound of rage and anguish, and releases a volley of spinners as ineffectual as the first.

Vakama's patience – or whatever had held him in place until now – snaps. He lunges forward. His claws close around the joints of Gaaki's rhotuka and pins the mechanisms harmlessly into place, in the same manner one might pick up a baby ussal crab by the widest edge of its shell. She thrashes, but Vakama's grip holds.

"I said, stop," he snarls.

She's breathing hard, her gasps sharp-edged with agony. "You killed him," she says, voice hoarse and hateful.

His insides twist, and – Gaaki hauled by his side – he starts the ascent to where the rest of the Rahaga are trapped. He doesn't look back to the rubble. Doesn't glance for one last glimpse of Norik's resting place.

He's not dead. He's not dead he's not dead he's not

The wrongness, the hatred, has woven so deep into him, it's almost a part of him now.

Toa don't kill. Vakama can't remember who taught him that (he recalls, briefly, the flash of a gold mask, but it comes with pain – grief – and he pushes it aside before it can take root) but it gnaws at him like a trapped stone rat. Toa don't kill.

But he was never meant to be one.

And if the Great Temple – if Mata Nui – thinks a mistake was made in Vakama's destiny....

Well. That's somebody else's problem.

x

The Hordika that returns to Roodaka is different from the one she sent out. There's something new in his eyes... or perhaps something lost.

"How was the temple, Vakama?" she asks when it's just the two of them.

He looks to her. Beneath the anger, beneath the rahi, there's almost a haunted look to those eyes. It vanishes a moment later, but Roodaka never doubts her own eyes.

"Unwelcoming," he replies, and Roodaka smiles. She could have suggested Vakama pick the Rahaga off one by one in the chaos of Metru Nui, outside where her Visorak could have been an aid... but the temple had been too good an opportunity to miss.

"Good." She sets a hand on his shoulder. "You owe no loyalty to Mata Nui, Vakama. Not anymore."

He rolls his shoulder, but not sharp enough to dislodge Roodaka's hand.

"One thing I do not understand," she says. "What happened to the sixth Rahaga?"

The Toa growls. It is a gutteral sound, rooted deep in the chest and at home in a way it wasn't before. "You wanted a message left for the other Toa. I needed a messenger."

"Alive?"

Vakama shrugs his shoulder again, and this time she lets him roll her hand loose. "Does it matter, so long as they understand?" he growls.

No, Roodaka concedes as she surveys the remains of the Toa before her. She supposes not.

#bionicle#cat writes#lego bionicle#do i have a weakness for the hordika arc? you'll never know#(yes. look i was a well behaved 12year old kid who loved plots about characters going feral. i ate the hordika plotline up)#(and two decades later or there abouts i still have nostalgic fondness for it)#heya so how do we feel about vakama returning to the temple and finding it is repulsed by him?#a discovery that might not only confirm he wasnt chosen by mata nui but has been forsaken#and yeah this was the fic i technically titled 'damned'#but also casually thought of it as 'god called to let you know he hates you personally'#because that's definitely a normal thing to name a fic#also yes i like the idea that roodaka pushed vakama to enter the temple knowing he would feel abandoned by mata nui#and thus helps sever the 'destiny' part of the three virtues#i like the idea that just like matau had to invoke the three virtues to get vakama back#roodaka worked on severing vakamas ties to the three virtues to get him to turn his back on the others#and while she succeeded with unity and destiny#duty she could only derail or corrupt rather than sever entirely#and that (esp since duty is vakamas whole shtick) is why matau reminding him of his duty finally worked#i'll probably add this and the stasis tube au to ao3 in time#but for now it goes here

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bella’s Selfish Investment in Jacob and Renesmee’s Relationship

In Twilight, Bella Swan’s acceptance of Jacob Black imprinting on her newborn daughter, Renesmee, is often presented as a result of her trust in Jacob and her belief in the supernatural mechanics of imprinting. However, a deeper analysis of her motivations reveals a more self-serving reason: Bella gets to have everything she wants without making any sacrifices. She chooses Edward and the immortal life of a vampire while still keeping Jacob, her "best friend," tethered to her life and family. Her willingness to embrace the imprinting bond is less about what is best for Renesmee and more about preserving her own perfect reality.

Jacob as Bella’s Emotional Security Blanket

Throughout the series, Bella struggles with the choice between Edward and Jacob. While her romantic love for Edward ultimately wins, she still harbors a deep emotional attachment to Jacob. When she chooses Edward, she knows it causes Jacob immense pain, which in turn makes her feel guilty. Jacob imprinting on Renesmee provides her with an instant resolution to this dilemma—he is now bound to her family forever, but in a way that removes the romantic conflict. This means Bella can keep Jacob close without feeling guilty for breaking his heart. She never truly has to let him go, making imprinting an incredibly convenient solution for her emotional struggle.

The Illusion of a “Perfect Family”

Bella has always wanted Jacob to be a part of her family, and imprinting makes this a reality. She directly admits to wanting Jacob in her life permanently, even imagining a scenario in which he was her cousin or brother. When Jacob imprints on Renesmee, it cements his role in her life in a way that does not threaten her relationship with Edward. For Bella, this is the best of both worlds: she gets her soulmate, and she also gets to keep her best friend as part of her new vampire existence.

This arrangement creates an illusion of a perfect family dynamic, where past heartbreaks and conflicts are erased. However, this vision depends entirely on Renesmee reciprocating Jacob’s imprint-induced feelings when she comes of age. If she were to reject Jacob, it would disrupt Bella’s carefully maintained fantasy of unity and harmony.

Why Renesmee’s Rejection of Jacob Would Shatter Bella’s Illusion

If Renesmee were to reject Jacob, Bella would be forced to confront the uncomfortable truth that imprinting does not guarantee happiness. This would mean that Jacob’s lifelong devotion was not a perfect solution after all, and it would also bring back Bella’s unresolved guilt about the pain she caused him. If Renesmee does not fulfill her supposed destiny by loving Jacob in return, Bella’s carefully maintained illusion of a happy, conflict-free family would crumble.

Additionally, Bella’s acceptance of imprinting hinges on the idea that it is an inescapable fate. If Renesmee were to exercise agency and refuse the bond, it would challenge the very foundation of Bella’s justification for Jacob’s role in her life. She would have to admit that she enabled a potentially harmful dynamic rather than a predestined romance, which would make her complicit in Jacob’s suffering rather than a passive bystander.

Bella’s Subconscious Investment in Jacob’s Happiness

At her core, Bella wants to feel absolved of the guilt she carries over choosing Edward and rejecting Jacob. If Renesmee accepts Jacob as her partner, it means that Bella’s decision did not ultimately hurt Jacob in the long run—it would mean that everything worked out "as it was supposed to." Her investment in their relationship succeeding is not purely about what is best for her daughter but about what makes her feel better about herself.

By securing Jacob within her family, she removes any lingering sense of regret, allowing herself to believe that she never truly lost him—he just took on a different role. This subconscious investment is what makes it crucial for her that Renesmee and Jacob end up together. If they do not, it disrupts the narrative she has built for herself, one in which no one really loses, and all choices lead to a happy ending.

Conclusion

Bella’s acceptance of Jacob imprinting on Renesmee is not just about trusting the supernatural process—it is about securing her own ideal reality. By ensuring Jacob remains in her life without romantic complications, she gets to have it all: her eternal love with Edward and the continued presence of her best friend. However, this vision depends entirely on Renesmee conforming to expectations. If she were to reject Jacob, Bella would have to face the fact that imprinting does not erase past pain and that her perfect family was built on a fragile foundation. Her support for their relationship is, at its core, a means of self-preservation—allowing her to avoid confronting her guilt while maintaining the illusion that no one ever truly got hurt.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sword of Avalon is an interactive novel based within the world of Arthurian Legends. With a three-person team writing it.

Genre(s): Fantasy, Angst, Adventure, Action, Romance, and Hurt/Comfort.

Warning(s): This game is rated 18+ for depictions of violence, blood, death, sexual themes, profanity, alcohol consumption, mentions of torture, and war.

Scenario and NSFW (within reason) asks are welcomed.

DEMO (TBA) || FAQ

Only the true King of England may pull the sword from the stone...

It was a legend that had flooded Camelot with hopeful individuals seeking to see if they were the destined heir, from the most gallant of knights to the poorest of beggars. None of them succeeded-- no one believing the sword could be pulled-- until a boy accomplished what no other could. Not only becoming the King of England but the ruler that promised unity after a world filled with strife.

Never knowing that over a decade later he’d come face-to-face with the physical embodiment of the sword that was forever by his side; a being that has come in a time when Camelot needs them the most.

For if they lost there wouldn’t be anything left to live for.

Play as the corporeal embodiment of the legendary sword Excalibur. Wherein you’re sent from Avalon to the wondrous world of Camelot to help defeat a coming darkness that threatens to swallow the world. Will you find love along the way? And even a family?

Customizable MC: name, gender, sexuality, appearance, and a smattering of other things.

Meet a variety of people that will show you what it’s like to have a family. Along with the castle hounds that may have a greater impact than you originally thought.

Romance 1 of 5 ROs; from King Arthur himself to a hot-headed, but loyal, Knight of the Round Table. (3 ROs are gender-selectable, 1 is male, and 1 is female.) Possibility of Poly Routes (don’t know yet).

Discover all the wonders of Camelot as you get to learn about the people living within it.

Dream about Avalon and have visions about the coming darkness.

Will you be able to save Camelot and, by extension, Avalon? Or will it all fall?

Arthur Pendragon [M] - The King

29 [6′5″ || Azure Blue Eyes || Golden Hair]

The King of Camelot-- and the wielder of Excalibur-- Arthur is a kind-hearted man who wouldn’t hesitate in defending anyone he believes needs it. While some may call him naive, and too pure of heart to sit on the throne, Arthur has proven himself time and time again with his ability in leading. Will you be the thing that he’s been missing all this time? Is the connection you feel with him something more than him just wielding Excalibur?

“I don’t know how this is possible, but I do know that I never want to let you go. I’ve waited my entire life for you. I-I think pulling Excalibur from the stone was in my destiny all along. Not to become the King of England, but to meet you.”

Vivien Lunete [F] - The Servant

27 [5′5″ || Slate Gray Eyes || Dark Brown Hair]

One of the first people that you meet upon entrance of Camelot. Soft spoken, with a surprisingly insightful look on life, she makes an impression on you automatically; not to mention the feeling that you’ve met her somewhere before. You don’t know what will happen in the coming days, but you hope that you’ll be able to get to know her more.

“You are more precious to me than any stone, my beloved, I would gladly lay upon a pyre and light it on fire if it meant keeping you safe. There is nothing that I wouldn’t do to keep you.”

Morgan/Morgana Le Fay [M/F] - The Sorcerer

28 [6′3″ || Emerald Green Eyes || Raven Black Hair]

The half-sibling of King Arthur that tends to stick to the shadows of the castle. Their sarcastic tone only softening slightly when dealing with their brother but for everyone else it’s mainly thinly veiled exasperation. Will you be able to get past the icy exterior of their heart? Seeing what no one else, but Arthur, has ever seen before?

“I’ve been called many things in my life, darling, but I think the sweetest is being able to be called yours. Just as I’m able to call you mine. Wherever our paths may lead us in the future, I’m sated with the knowledge that they’re intersected at least once.”

Emrys/Emrya Wyllt [M/F] - The Court Wizard

(Looks) 33 [5′8″ || Hazel Eyes || Silver-White Hair]

The Wizard of King Arthur’s Court-- also known as Merlin-- who isn’t at all what you were expecting upon meeting them. Their youthful face, for one, didn’t fit with the tales of an aged man guiding the young king; not to mention their cheerful disposition towards life. However, don’t let their appearance dissuade you as their magic hums just underneath the surface... waiting to be unleashed.

“I may have power the likes many wish to, but you have a power too, dearest one. You have entrapped me more than any spell ever could. I am yours for as long as you’ll have me.”

Caelian/Caelia Aphelion [M/F] - The Knight

29 [5′10″ || Dark Brown Eyes || Auburn Hair]

With a temper as fiery as their hair, this reputable Knight of the Round Table is known far and wide, with an added bonus of their prowess in battle, they’re quite feared. Extremely loyal to the ones that have earned their trust-- namely Arthur-- they would fight till the bitter end to stay by their side.

“I-I’ve never felt this way about anyone before. I-I’ve never let myself get this close, but I just wanted to thank you for giving me a chance. For seeing past the anger to what I’ve been hiding from for so long. Thank you for seeing me.”

#the sword of avalon#cscript#choice script#interactive novel#interactive fiction#no demo yet#arthurian legend

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

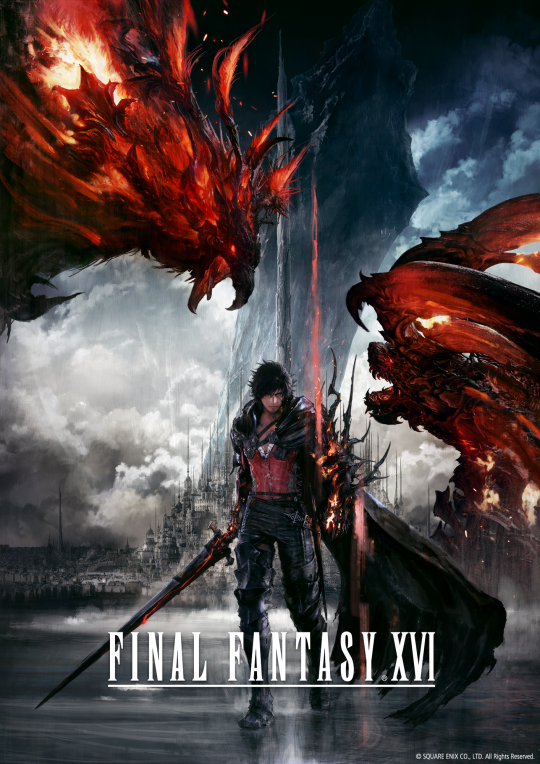

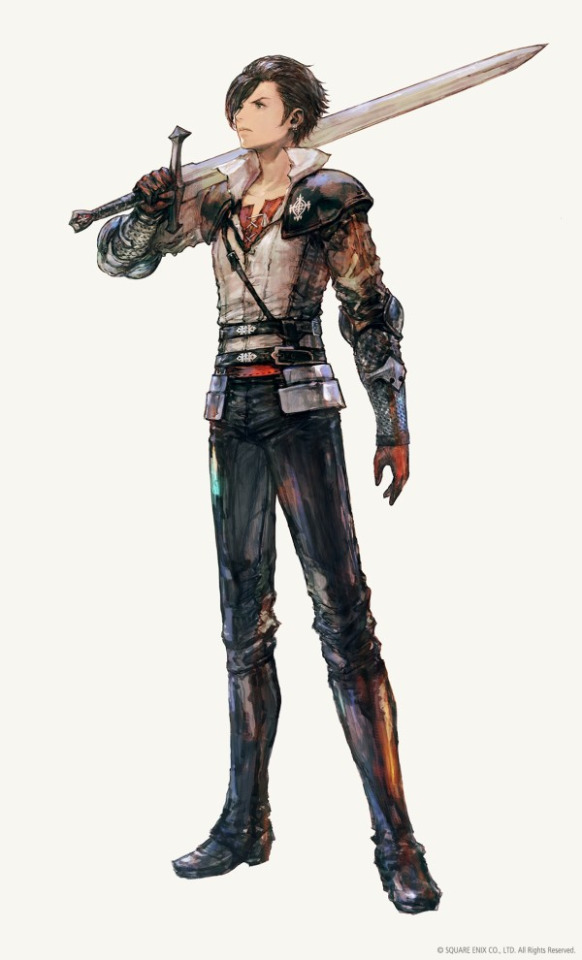

Final Fantasy XVI details the world and characters

■ Key Visual

—Protagonist, Clive Rosfield, on a dark and dangerous road to revenge.

Final Fantasy XVI brings players into a world where Eikons are powerful and deadly creatures that reside within Dominants—a single man or woman who is blessed with the ability to call upon their dreaded power. The story follows Clive Rosfield, a young man dedicated to mastering the blade, who is dubbed the First Shield of Rosaria and tasked to guard his younger brother Joshua—the Dominant of the Phoenix. Unexpected events set Clive on a dark and dangerous road to revenge.

■ World

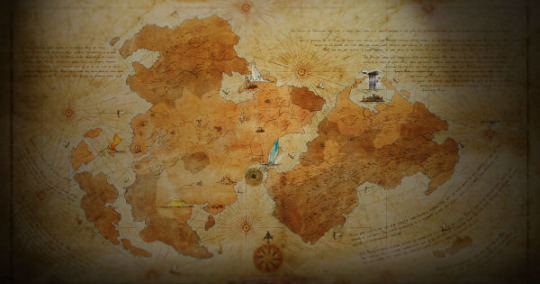

Valisthea―A Land Blessed in the Light of the Mothercrystals

The land of Valisthea is studded with Mothercrystals—glittering mountains of crystal that tower over the realms around them, blessing them with aether. For generations, people have flocked to these beacons to take advantage of their blessing, using the aether to conjure magicks that let them live lives of comfort and plenty. Great powers have grown up around each Mothercrystal, and an uneasy peace has long reigned between them. Yet now the peace falters as the spread of the Blight threatens to destroy their dominions.

Eikons and Their Dominants

The Eikons are the most powerful and deadly creatures in Valisthea. Each resides within a Dominant—a single man or woman who is blessed with the ability to call upon their dread power. In some nations these Dominants are treated as royalty in admiration of this strength—in others they are bound in fear of it, and forced to serve as weapons of war. Those who are born as Dominants cannot escape their fate, however cruel it may be.

The Realms of Valisthea

—The Grand Duchy of Rosaria

Long ago, a group of small independent provinces in western Valisthea found strength in unity, and formed the Grand Duchy of Rosaria. After years of relative prosperity, the duchy now finds itself threatened by the spread of the Blight—a threat that, left unchecked, would doubtless usher the realm to ruin. Rosaria draws its aether from Drake’s Breath, a Mothercrystal situated on a volcanic island off the coast. The Dominant of the Phoenix, Eikon of Fire, is enthroned as Archduke when they come of age.

—The Holy Empire of Sanbreque

Sanbreque is the largest theocratic force in Valisthea. The Empire’s holy capital Oriflamme is built around Drake’s Head, the Mothercrystal that blesses the surrounding provinces with abundant aether. The people happily take advantage of this, living in comfort and security under the watchful gaze of the Holy Emperor, whom they worship as the living incarnation of the one true deity. The Dominant of serves as the empire’s champion, taking to the field in times of war to rout its enemies.

—The Kingdom of Waloed

Waloed claims the entirety of Ash, the eastern half of Valisthea, as its dominion. The kingdom’s control of the continent has oft been tested by the orcs and other beastmen who make their home there, but the current ruler of the realm—Dominant of —has succeeded in quelling their rebellions. Using the power of the kingdom’s Mothercrystal, Drake’s Spine, this new king has built up a mighty army, with which he now seeks to test the borders of his neighbors.

—The Dhalmekian Republic

The Dhalmekian Republic is made up of five states, from which the members of its ruling parliament are drawn. Its Mothercrystal, Drake’s Fang, is half-hidden in the heart of a mountain range—the republic’s control over it, and its aether, securing the obedience of the large part of southern Valisthea. The Dominant of Titan, Eikon of Earth, is installed as a special advisor to parliament and has a significant say in its decision-making.

—The Iron Kingdom

A small group of islands off the coast of Storm, the western half of Valisthea’s twin realms. Here the Crystalline Orthodox, an extreme faith that worships crystals, reigns supreme. The Iron Kingdom controls Drake’s Breath, the Mothercrystal that sits at the heart of one of their islands—long a source of contention with neighboring Rosaria. Isolated and aloof from the mainland nations, the Ironblood speak their own language. Orthodox doctrine judges Dominants to be unholy abominations, and any unlucky enough to be born on the islands are executed.

—The Crystalline Dominion

The Crystalline Dominion sits at the heart of Valisthea, built around the tallest of all the Mothercrystals, Drake’s Tail. Many bloody battles were fought for control of this small plot of land due to its strategic importance, till the warring realms finally agreed to an armistice. As part of the peace treaty, the islands around Drake’s Tail became an autonomous dominion led by a council of representatives from the surrounding nations—each realm enjoying equal claim to the Mothercrystal’s blessing. No Dominant makes their home there.

■ Characters

character artwork by Kazuya Takahashi

Clive Rosfield (age 15)

The firstborn son of the Archduke of Rosaria. Though all expected him to inherit the Phoenix’s flames and awaken as its Dominant, destiny instead chose his younger brother Joshua to bear this burden. In search of a role of his own, Clive dedicated himself to mastering the blade. His practice pays off when, at just fifteen years of age, he wins the ducal tournament and is dubbed the First Shield of Rosaria—tasked to guard the Phoenix and blessed with the ability to wield a part of his fire. Alas, Clive’s promising career is to end in tragedy at the hands of a mysterious dark Eikon, Ifrit, setting him on a dangerous road to revenge.

Joshua Rosfield (age 10)

The second son of the Archduke of Rosaria and Clive’s younger brother by five years. Joshua awoke as the Dominant of the Phoenix soon after his birth. Despite his noble upbringing, Joshua treats all his father’s subjects with warmth and affection—none more so than Clive, whom he deeply admires. Joshua often laments that it was he, the frail and bookish younger son, who was granted command of the firebird’s flames, and not his stronger, braver brother. While Clive will gladly throw himself into any danger, Joshua quails at the sight of a carrot on his dinner plate. But carrots become the least of his concern when he, too, is swept up into the tragic events that change Clive’s life forever.

Jill Warrick (age 12)

Born in the fallen Northern Territories, Jill was taken from her homeland at a tender age to become a ward of Rosaria, securing peace between the two warring nations. The Archduke insisted that she be raised alongside his sons, and now, at twelve years of age, she is as much a part of the Rosfield household as Clive and Joshua. Ever kind, gracious, and unassuming, Jill has become a trusted confidant to the brothers.

Final Fantasy XVI is in development for PlayStation 5.

274 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Pelle/Dani Receipts: Post One, Introduction

Hello and welcome to Rimanez and AnonLady present: Midsommar: The Pelle/Dani Receipts.

Are you sitting comfortably? Got your tea with special properties, rune-stitched white linen solstice clothing, and flower crown? Then let’s begin. Skål!

We are going to step you through the film more-or-less chronologically, detailing evidence supporting the Pelle/Dani ship in dialogue and behavior, cinematography, costuming, set design, and artwork featured throughout the film. This will include not just the signs that Pelle loves Dani--compelling, but low-hanging fruit when discussing this ship--but that Dani has feelings for Pelle, that their onscreen intimacy indicates a friendship, at least, that is independent of their individual relationships to Christian, and that Dani and Pelle are destined for each other. We should note that Ari Aster is meticulous, so meticulous, and it’s possible there are still things we have missed and perhaps some of our interpretations you may disagree with. That’s fine! We’ve got a lot to work with here. Additionally, while we will touch on elements relating to Dani’s destiny as May Queen, we will concentrate on those elements that pertain to her destiny with Pelle specifically.

There will be 12 individual posts, which Rimanez and I will be posting over the course of the next week or so as we get them ready, two at a time, with each post hyperlinked to the succeeding post, and then at the end, we’ll have a convenient table of hyperlinks.

All gifs and high quality images have been wrangled by @amy-amell. Rune expertise will be provided by @daydreamers.

Before we get into specific evidence, a brief word about general motifs to be aware of in Midsommar. These are not things that directly speak to the Pelle/Dani romance, but will feature in scenes we discuss and contribute to their meaning. These include:

The color yellow. Yellow generally relates to Dani’s journey, her yellow brick road. For example: the prevalence of the color in the Ardor house, particularly in pictures of Dani and the flower arrangement over the bedside picture of her; the hose that Terri uses to pipe the gas fumes into the upstairs is yellow; the path through the woods to Hårga features a thickening carpet of yellow flowers; the yonic sun gate to Hårga is yellow; Dani’s flower crown during the competition is mainly yellow; the Fire Temple, of course, is bright yellow.

The sun. While they’re not sun worshipers, per se, the sun is the ultimate symbol of Hårgan belief in the Great Cycle. It also effectively doubles as a symbol for Dani’s destiny to join the family at the end, folding in the significance of the color yellow. Also note that in Old Norse myth, the sun is female and the moon is male, as opposed to Western traditions, which makes sense since, while it’s not explicitly stated, Hårga seems to be a matriarchy, with Siv as head honcho and the May Queen ultimately given the power of life and death in the Fire Temple ceremony.

The color blue. Blue generally relates to the Hårgans. You will notice it in their special solstice clothes’ embroidery, but also in sneakier places, like the lit trees behind Christian as he approaches Dani’s apartment to, sigh, sorta hold her in the beginning.

Flowers and plants. Flowers, plants everywhere. Not just real ones, but design elements, too, everywhere from Dani’s parents’ room to Hårga. Flowers, of course, have their own subtle language -- brilliantly and comprehensively explored in this post -- not unlike the Hårgans, but you will notice their presence waxes as Dani comes home to Hårga. In addition to the individual meanings of certain plants and flowers, note their generic connotations of sex, nature, growth, and balance. As Pelle muses in the meadow, “Nature just knows instinctually how to stay in harmony.” And that’s the essence of Dani’s journey: finding the harmony and balance she lacks.

Mirrors. Mirrors indicate something going on beneath the surface. We first see Dani’s parents, apparently sleeping, reflected in their bedroom mirror as Dani’s call goes to voicemail, only to learn they were actually dead. Christian’s lies to Dani, his friends, and himself are reflected in mirrors at Dani’s apartment and his own. Dani has her terrifying glimpse of Terri in the bathroom mirror. We first meet Maja primping in a mirror, and we soon learn she’s not just primping but primping for a plot. And most importantly for this piece, we see Pelle reflected in a mirror while sketching the newly-crowned May Queen, but of course, even in that idyllic moment, he is still plotting to get Christian out of the way. Mirrors = look again.

OK, with those principal motifs set to one side, let’s look at general underlying evidence of Pelle and Dani destiny, shall we?

Names. Dani Ardor. Ardor means love or passion and it comes from the Latin word ardere: to burn. Her first name, like sister Terri’s, is a male-sounding female name, a time-honored convention for Final Girls in horror movies. It also recalls Danny from The Shining (1980), a film that is referenced visually in the soaring overhead shots of the journey to Hårga, but also in the design of Dani’s bedsheet in the Hårgan Youth House.

It’s also worth noting that Dani is a common short form of Danielle, which literally means “God is my judge.” Taken alongside Dani’s ultimate judging of Christian, that’s...pretty suggestive. (Big thanks to @henrys-side-blog for pointing this out!)

Pelle is a name on its own and a pet form of Per, both Swedish forms of Peter, from the Greek petros, stone or rock, i.e. the foundation. It brings to mind the Ättestupa, the ultimate symbol of Hårgan unity, and the way that Pelle offers himself as a support for Dani, too. There’s also the association with Peter, the disciple who denied Christ. I mean...his romantic rival’s name is Christian, although Ari Aster says there are lots of ways to read Christian’s naming...which he won’t tell us. “He is thrown to the lions, so to speak.”

Lastly, this may just be a coincidence, but Dani has unique pronunciations of both Pelle and Christian that differ from the way the rest of the cast pronounces their names. (OK, I think Mark says Pell-ay once.) This is in spite of Florence Pugh’s flawless American accent, and it’s not replicated with any characters that aren’t Dani’s love interests. It’s just weird.

Dani and Pelle’s Costuming. After arriving, Pelle initially only dons a Hårgan shirt while retaining the rest of his outsider clothing. Dani dons a Hårgan apron initially before changing into full Hårgan costume for the maypole dance. Their costuming throughout the movie, as with many of their movements and behaviors, show a continuous synchrony that also charts Dani’s assimilation into the family. It’s worth noting that Pelle doesn’t kiss her until they are both in full Hårgan dress.

Runes are another big underlying source of meaning, but frankly, they are so complex and multivalent, including elements that we only really discovered while working on this post, they are going to get their own section at the end, where all of our contextual evidence will help guide interpretation.

OK, let’s crack the film open and find us a love story.

The Pelle/Dani Receipts Masterpost

217 notes

·

View notes

Link

Square Enix has launched the teaser website for Final Fantasy XVI, which features the key artwork and information on the game’s setting and main characters.

Get the details below.

■ Key Visual

—Protagonist, Clive Rosfield, on a dark and dangerous road to revenge.

Final Fantasy XVI brings players into a world where Eikons are powerful and deadly creatures that reside within Dominants—a single man or woman who is blessed with the ability to call upon their dreaded power. The story follows Clive Rosfield, a young man dedicated to mastering the blade, who is dubbed the First Shield of Rosaria and tasked to guard his younger brother Joshua—the Dominant of the Phoenix. Unexpected events set Clive on a dark and dangerous road to revenge.

■ World

Valisthea―A Land Blessed in the Light of the Mothercrystals

The land of Valisthea is studded with Mothercrystals—glittering mountains of crystal that tower over the realms around them, blessing them with aether. For generations, people have flocked to these beacons to take advantage of their blessing, using the aether to conjure magicks that let them live lives of comfort and plenty. Great powers have grown up around each Mothercrystal, and an uneasy peace has long reigned between them. Yet now the peace falters as the spread of the Blight threatens to destroy their dominions.

Eikons and Their Dominants

The Eikons are the most powerful and deadly creatures in Valisthea. Each resides within a Dominant—a single man or woman who is blessed with the ability to call upon their dread power. In some nations these Dominants are treated as royalty in admiration of this strength—in others they are bound in fear of it, and forced to serve as weapons of war. Those who are born as Dominants cannot escape their fate, however cruel it may be.

The Realms of Valisthea

—The Grand Duchy of Rosaria

Long ago, a group of small independent provinces in western Valisthea found strength in unity, and formed the Grand Duchy of Rosaria. After years of relative prosperity, the duchy now finds itself threatened by the spread of the Blight—a threat that, left unchecked, would doubtless usher the realm to ruin. Rosaria draws its aether from Drake’s Breath, a Mothercrystal situated on a volcanic island off the coast. The Dominant of the Phoenix, Eikon of Fire, is enthroned as Archduke when they come of age.

—The Holy Empire of Sanbreque

Sanbreque is the largest theocratic force in Valisthea. The Empire’s holy capital Oriflamme is built around Drake’s Head, the Mothercrystal that blesses the surrounding provinces with abundant aether. The people happily take advantage of this, living in comfort and security under the watchful gaze of the Holy Emperor, whom they worship as the living incarnation of the one true deity. The Dominant of serves as the empire’s champion, taking to the field in times of war to rout its enemies.

—The Kingdom of Waloed

Waloed claims the entirety of Ash, the eastern half of Valisthea, as its dominion. The kingdom’s control of the continent has oft been tested by the orcs and other beastmen who make their home there, but the current ruler of the realm—Dominant of —has succeeded in quelling their rebellions. Using the power of the kingdom’s Mothercrystal, Drake’s Spine, this new king has built up a mighty army, with which he now seeks to test the borders of his neighbors.

—The Dhalmekian Republic

The Dhalmekian Republic is made up of five states, from which the members of its ruling parliament are drawn. Its Mothercrystal, Drake’s Fang, is half-hidden in the heart of a mountain range—the republic’s control over it, and its aether, securing the obedience of the large part of southern Valisthea. The Dominant of Titan, Eikon of Earth, is installed as a special advisor to parliament and has a significant say in its decision-making.

—The Iron Kingdom

A small group of islands off the coast of Storm, the western half of Valisthea’s twin realms. Here the Crystalline Orthodox, an extreme faith that worships crystals, reigns supreme. The Iron Kingdom controls Drake’s Breath, the Mothercrystal that sits at the heart of one of their islands—long a source of contention with neighboring Rosaria. Isolated and aloof from the mainland nations, the Ironblood speak their own language. Orthodox doctrine judges Dominants to be unholy abominations, and any unlucky enough to be born on the islands are executed.

—The Crystalline Dominion

The Crystalline Dominion sits at the heart of Valisthea, built around the tallest of all the Mothercrystals, Drake’s Tail. Many bloody battles were fought for control of this small plot of land due to its strategic importance, till the warring realms finally agreed to an armistice. As part of the peace treaty, the islands around Drake’s Tail became an autonomous dominion led by a council of representatives from the surrounding nations—each realm enjoying equal claim to the Mothercrystal’s blessing. No Dominant makes their home there.

■ Characters

Clive Rosfield

The firstborn son of the Archduke of Rosaria. Though all expected him to inherit the Phoenix’s flames and awaken as its Dominant, destiny instead chose his younger brother Joshua to bear this burden. In search of a role of his own, Clive dedicated himself to mastering the blade. His practice pays off when, at just fifteen years of age, he wins the ducal tournament and is dubbed the First Shield of Rosaria—tasked to guard the Phoenix and blessed with the ability to wield a part of his fire. Alas, Clive’s promising career is to end in tragedy at the hands of a mysterious dark Eikon, Ifrit, setting him on a dangerous road to revenge.

Joshua Rosfield

The second son of the Archduke of Rosaria and Clive’s younger brother by five years. Joshua awoke as the Dominant of the Phoenix soon after his birth. Despite his noble upbringing, Joshua treats all his father’s subjects with warmth and affection—none more so than Clive, whom he deeply admires. Joshua often laments that it was he, the frail and bookish younger son, who was granted command of the firebird’s flames, and not his stronger, braver brother. While Clive will gladly throw himself into any danger, Joshua quails at the sight of a carrot on his dinner plate. But carrots become the least of his concern when he, too, is swept up into the tragic events that change Clive’s life forever.

Jill Warrick

Born in the fallen Northern Territories, Jill was taken from her homeland at a tender age to become a ward of Rosaria, securing peace between the two warring nations. The Archduke insisted that she be raised alongside his sons, and now, at twelve years of age, she is as much a part of the Rosfield household as Clive and Joshua. Ever kind, gracious, and unassuming, Jill has become a trusted confidant to the brothers.

Final Fantasy XVI is in development for PlayStation 5.

View the artwork above in high-resolution at the gallery.

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

History

Are you watching from your pit in Hell, father? Do you understand now? That it was always my destiny... never yours. The Red Skull's failure will be his daughter's triumph... and I will reshape this world.SIN

Early Life

Sinthea "Sin" Shmidt is the daughter of the Red Skull. Seeking a male heir, the Red Skull fathered a daughter with a washerwoman. The woman died in childbirth, and the Red Skull almost killed the child, angry that it was a girl and not the boy he expected. One of his followers, Susan Scarbo, convinced him not to, telling him she would raise the girl herself as her nanny. The Skull agreed and left the girl (now named Sinthea) to be raised by Scarbo, who indoctrinated her with the Skull's views as she grew up. The Skull returned when Sinthea was a child and put her in a special machine that accelerated her aging process until she was an adult and gave her superhuman powers.[7]

Mother Superior

Afterwards, as Mother Superior, Sinthea became the leader of a group called the Sisters of Sin; young orphan girls who were accelerated into adulthood and given powers by the Red Skull after being indoctrinated by Sinthea. The Sisters of Sin would have many run-ins with the Red Skull's nemesis Captain America before being de-aged when they entered a chamber designed to reverse the Skull's aging process to assault Captain America - who had suffered through the Skull's process and had become elderly - while he was using it to return himself to normal, and they were reverted to children at the same time Captain America was restored (she would later claim she was de-aged to the wrong age - but whether this is true, and in which direction, is unclear).[8]

Sister Sin

Later, Scarbo (now calling herself Mother Night), reformed the Sisters of Sin and became their new leader, while the de-aged Sinthea took the name Sister Sin.[9]

Sin

Sinthea was later captured by S.H.I.E.L.D. and taken to their re-education facility, where they attempted to reprogram her to be a "normal" American girl and gave her false memories to that effect. Later, the Red Skull was assassinated by the Winter Soldier under the orders of Aleksander Lukin, and one of the Skull's henchmen, Crossbones, broke into the facility and kidnapped Sinthea. Crossbones tortured Sinthea to break S.H.I.E.L.D's conditioning. After he succeeded, she entered into a relationship with him, and - with Sinthea now calling herself simply Sin - the two went on a killing spree. They later reunited with the Skull, now living inside the mind of General Lukin.[10]

As the first part of the Skull's Master Plan, Sin disguised herself as a nurse after the Civil War while Crossbones sniped Captain America at the courthouse, even though it meant obeying her father and abandoning Crossbones to his fate. Sin then revealed to Sharon Carter that she was the one who had killed Cap.[11]

While the Red Skull had control over Steve Rogers' body, Sin fought alongside Crossbones against the Avengers' forces. After Steve Rogers eventually regained control of his body, Sin was knocked unconscious. After the battle, and due to a subsequent explosion, Sin's face was left severely disfigured and scarred, leaving her a "red skull" appearance. Upon hearing the news, Norman Osborn quipped, 'Like father like daughter'.[12]

Sin was institutionalized at the Kurtzburg Institute for the Criminally Insane People. During a breakout/riot, she was approached by Helmut Zemo, who asks her to tell him how to kill Bucky Barnes. More recently, Sin was liberated from the asylum by Master Man who has proclaimed both his allegiance and affection to Sinthea as the new Red Skull: the heir to her (believed deceased) father's legacy. [4]

Fear Itself

After taking the Black Widow and Sam Wilson hostage, Sin sent one of her henchmen to disrupt the trial of Captain America and sent a demand: Bucky Barnes. After escaping with help from the manipulative Doctor Faustus, James confronted Sin and Master Man and brashly attempted to foil her escape. After the escape, Sin allied herself once more with Baron Zemo to retrieve the Book of the Skull, with which she would discover the whereabouts of a hammer her father summoned way back in 1942. After successfully retrieving the book and explaining its origins to Zemo, Sin betrayed him and went on her own to retrieve the hammer for herself.[13]

Sinthea as Skadi.Sin and her henchmen went to the stronghold of the Thule Society housing the hammer, invaded it and killed everyone who crossed her path. After finding the hammer and being deemed worthy by it, Sin, now as Skadi, went to set her new master, the Serpent, free.[6] At her father's order, Skadi led an assault on Washington D.C.,[14] during which, she almost killed Bucky Barnes.[15] Skadi soon reached New York, where she faced off against Steve Rogers, who had returned as Captain America.[16] There, she summoned the Serpent. When the Avengers tried to take him down, he broke Rogers' shield and knocked out the team.[17] By her father's side, Skadi and the other Worthy went to the fallen Asgard, in Broxton, Oklahoma, where they battled the Avengers once more. Sin was taken down by Rogers, who was wielding the mystic Mjolnir. After the Serpent was killed by Thor, Sin's hammer was taken from her by Odin, as well as the hammers of the other Worthy.[18]

Search for Power

Suddenly, Sin woke up in a hideout where strange people said they freed her from custody and they would help to find her hammer again.[18]

All-New Captain America

While on a mission to neutralize a new Hydra base in Ecuador, the new Captain America Sam Wilson was teleported along with his comrade, Nomad, from there to Helmut Zemo's palace in Bagalia through the Infinite Elevator. There, several super-agents of the new Hydra were expecting Cap and Nomad, with Sin being one of them.[19]

After Zemo killed Ian, Sam, with an undercover Misty Knight, that helped him before in a fight against Crossbones,[20] went to the Hydra's castle, only to be welcomed by Sin herself. There, the Red Skull's daughter faced Wilson while enjoying a reconstitution of the World War II through holographic technology. Sin started to mock Sam, saying that if it wasn't for her father, Sam wouldn't have become a hero, but only a low-level gangster by the name of "Snap Wilson". Sam, offended by her words, tried to attack her, only to discover that the Sisters of Sin were holding the members of his family, such as his sister and his niece, to ransom. If Sam attacked Sinthea, she'd order to her sisters to kill his family instantly. Sin made Sam give his shield and his wings to her, then ordered him to commit suicide by jumping off a cliff.

Soon after, she started a video conference with Crossbones, Baron Zemo and Taskmaster, saying that the plan to defame Wilson was successful and, after saying that she was better than her father, that she was the real and only Red Skull, she activated Zemo's plan: to spread worldwide the toxic blood of an Inhuman named Lucas, capable of sterilizing human beings, by launching a bomb into Earth's atmosphere. Zemo's plan was to create a new perfect world ruled by Hydra, as its agents would be the only fertile humans after the great leveling, thanks to the Inhuman boy's blood. It was then that Sin was attacked by Sam, who was rescued by his pet Redwing. Sin seemingly met her fate when the bomb containing Lucas' blood was destroyed by Cap.[21]

Return

Allying herself with the��telepathic clone of her late father, Sin proposed him to create a new Hydra and use its agents to create deadly machines and infiltrate spy agencies, much to his dismay. Suddenly, a child appeared in front of them, and used her powers to fix Sin's face, returning it to how it was before the explosion that disfigured it. The girl then proceeded to explain she was made of a shard of a Cosmic Cube that once belonged to the Red Skull. Taking advantage of the situation, the Red Skull devised a new plan for his new Hydra.[22]

Sin helped her father retrieve a black box, as well as all his gold, from his safe in a bank in Bagalia, being nearly caught by the Avengers Unity Squad in the process if not by the Red Skull, who used his telepathic abilities to disguise himself as Gambit, and to cloak Sin and the contents of the safe from them.[23]

Sin and the Red Skull hid out in a secret underground room in the Avengers Mansion, which was no longer used by the Avengers and had been converted into a tourist attraction. The pair was nearly discovered by Quicksilver and Deadpool of the Avengers Unity Division, but the Red Skull used his telepathy to convince the heroes that the room was empty.[24]

Sin later took her father to Pleasant Hill, a prison disguised as a small town where the realities of the criminals would be rewritten to turn them into powerless and common people, during Zemo's insurrection in order to the Red Skull to use Kobik to rewrite Steve Rogers' past, turning him into a loyal agent of Hydra at his service.[25][22]

Powers and Abilities

Power Grid [28]Intelligence 2Strength*6 2Speed* 3 2Durability*6 2Energy Projection*5 1Fighting Skills4 * Higher ratings with Hammer of Skadi.

Powers

As Mother Superior, Sin possessed a range of superhuman powers including telepathy, telekinesis, teleportation and intangibility. After she was de-aged, she apparently lost these powers completely - unlike the other "Sisters of Sin", whose powers were diminished but not eliminated upon de-aging. The reason for this discrepancy is currently unclear.[1][26]

With the Hammer of Skadi, Sin has the powers associated with wielding an enchanted Asgardian weapon.[1][26]

Abilities

Being trained by her father, she is an expert hand to hand combatant and martial artist. She is also highly proficient in firearms and explosives. As the Red Skull's child, Sin also has a high level of intellect.[1][26]

Strength level

Normal human female[1][26]

Weaknesses

Same as that of a normal human female[1][26

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

More Perfect Unions

Posted on May 17, 2020 by outcandour

Raise your hand if you’ve had Never My Love stuck in your head since the finale! Let’s discuss Season 5.

Warning- Contains spoilers from Outlander Season 5 and Episode 512: Never My Love.

Wholeness, noun:

the state of forming a complete and harmonious whole; unity

the state of being unbroken or undamaged

To be honest, I wasn’t entirely sure I would recap the finale episode. Episode 512 was beautifully executed, with some of Caitriona Balfe’s finest acting, but writing the recaps requires multiple episode viewings and this one was tough to rewatch. My family has also had a rough week with a sad diagnosis for one of our pets; emotionally I haven’t quite been up for it. And so, as a bit of a compromise, I thought I would not only reflect on the finale, but also the season in its entirety.

Beyond the deeply textured and stunning set and costume designs of Claire’s mid-century dissociative scenes in Episode 512, what stands out to me is who was included and how they are included in this imaginary safe space: Murtagh is alive, Jocasta has her sight, and Fergus has both hands. Jamie this season first tells Roger and then Claire, “You are alive. You are whole.” The family members in these dissociative scenes are alive. They are whole. The underlying message breaking through Claire’s subconscious: you will be safe.

And looking back on Season 5 we can see that “wholeness” is a theme repeatedly addressed. What does it mean to be whole? Can a man be complete with only one leg? Can your identity survive if you lose your voice? Are we permanently broken if we lose our spouse, a lover, or a family member? Can a family survive if its members leave…perhaps forever? Are we still spiritually intact if we take another’s life? The finishing- the wholeness– of the Big House is a continued story in nearly every episode. In a world where a shattered opal provides clues to the past and future, this season examines what it takes to feel complete. Spiritually and physically and on the eve of the American Revolution, our characters work toward a more perfect union of mind and body.

Back in December and February I made a number of predictions regarding Season 5 (you can read them here and here), and I argued that the tone being set for this season was religious in nature. From the choral music employed in the new opening credits, to the multiple biblical references in the episode titles (Free Will, Perpetual Adoration, Better to Marry Than Burn, Mercy Shall Follow Me), this season frequently references fate and faith. Our characters repeatedly examine their spiritual wholeness, questioning their actions, morality, and place in a universe where time travel is possible and the future can be known. Isn’t this playing God, Brianna asks? Genesis and many other creation stories tell us that humankind was made complete with a physical body and spiritual soul…man was made whole. Much of this season focuses on free will and destiny, with our characters struggling their way back to that original state of completion.

Physically, our characters “take stock” of themselves more than once this season…personally examining their wholeness. Jamie inspects his body on the morning of his birthday (The Ballad of Roger Mac), while Claire surveys her injuries following her rape and beating (Never My Love). In both these episodes, however, the true “taking stock” is of their mind and spirit following intense trauma– affirmations that life goes on after their worlds feel shattered…after their worlds feel not quite whole. Claire promises she will survive, while Jamie pushes through his grief in order to help his family. Physically and spiritually, they know they will heal.

We know it, too. After eight novels and five seasons with these characters, we know they are individually capable of survival. Jamie and Claire spent twenty years apart, learning and growing despite their separation. Brianna and Roger each independently traveled to the past, more or less successfully making their way to their intended goals. Fergus and Marsali both survived difficult childhoods to form their own loving (and large) family. Ian often moves through this world alone, with Rollo as his sole companion. Everyone in this family has repeatedly proved they are competent when alone.

Yet Season 5 argues that although our main characters are individually qualified, they are most whole when united: I will fight for you, I will be loyal to you, I belong here, I was thinking of home. As Jamie affirms in the finale, “It is myself who kills for [Claire].” Our characters fill in the gaps in each other’s lives– where one cannot go another will tread. They take turns killing and saving, confessing their sins and offering absolution. One will push as another pulls. In this way they are more complete when together… together they are most whole.

Wholeness this season, then, is an unsurprising union of the physical and spiritual. Jamie’s leg heals, but he comes to recognize that his entire being transcends his physicality. Roger regains his voice and his will to live. Ian contemplates ending his physical life, but eventually heals his spirit enough to overcome such thoughts. Brianna, Roger, and Jem physically come back to their family, also gaining a realization of their sense of belonging. In the end the Fraser family has succeeded in achieving those definitions of wholeness: united and unbroken in body and spirit.

The glimmer of promise from the Season 5 finale may indeed be in Claire’s affirmation that she feels safe. But the sign of hope for me comes a few minutes earlier in the episode. Throughout the course of this series Brianna has effortlessly quoted Nathan Hale, Herman Melville, and Robert Frost. “Never quote an American to an American,” Roger once told her, knowing we eagerly consume our own history when it is fed. And so here is Outlander, offering it to us by the spoonful. Like the country that is forming, the Fraser family stands united. The storm clouds loom, the American Revolution approaches. Beyond that distant North Carolina horizon thirteen colonies will come together as one. They will come together to be whole.

Slàinte

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHAPTER IV THE UNION OF ATTICA AND THE FOUNDATION OF THE ATHENIAN DEMOCRACY

SECT. I. THE UNION OF ATTICA

When recorded history begins, the story of Athens is the story of Attica, the inhabitants of Attica are Athenians. But Attica, like its neighbour Boeotia and other countries of Greece, was once occupied by a number of independent states. Some of these little kingdoms are vaguely remembered in legends which tell of the giant Pallas who ruled at Pallene under the north-eastern slopes of Hymettus, of the dreaded Cephalus lord of the southern region of Thoricus, or of Porphyrion of mighty stature whose domain was at Athmonon under Mount Pentelicus. The hill of Munychia was, in the distant past, an island, and was crowned by a stronghold; the name Piracus has been supposed to preserve the memory of days when the lords of Munychia looked across to the mainland and spoke of the "opposite shore." At a later stage we find neighbouring villages uniting themselves together by political or religious bonds. Thus in the north, beyond Pentelicus, Marathon and Oenoe and two other towns formed a tetrapolis. Again Piraeus, adjacent Phaleron, and two other places joined in the common worship of the god Heracles, and were called the Four-Villages. Of all the lordships between Mount Cithaeron and Cape Sunium the two most important were those of Eleusis and Athens, severed from one another by the hill-chain of Aegaleos.

It was upon Athens, the stronghold in the midst of the Cephisian plain, five miles from the sea, that destiny devolved the task of working out the unity of Attica. This Cephisian plain, on the south side open to the Saronic gulf, is enclosed by hills, on the west by Aegaleos, on the north-west by Parnes, on the east by Hymettus, while the gap in the north-east, between Parnes and Hymettus, is filled by the gable-shaped mass of Pentelicus. The river Cephisus flows not far from Athens to westward, but the Acropolis was girt by two smaller streams, the Ilīsus and the Eridănus. We have seen that it had been occupied as an abode of men in the third millennium, and that in the bronze age it was one of the strong places of Greece. There still remain pieces of the wall of grey-blue limestone with which the Pelasgian lords of the castle secured the edge of their precipitous hill." The old wall was called the Pelargikon, but in later times this name was specially applied to the ground on the north-western slope. The Acropolis is joined to the Areopagus by a high saddle, which forms its natural approach, and on this sidewalls were so constructed that the main western entrance to the citadel lay through nine successive gates. At the north-western corner a covered staircase led down to the well of Clepsydra, which supplied the fortress with water; and on the north side there were two narrow "postern" descents into the plain, much steeper than that at Tiryns. We may take it that all these constructions were the work of the Pelasgians and were inherited by their Greek successors.

The first Greeks who won the Pelasgic acropolis were probably the Cecropes, and, though their name was forgotten as the name of an independent people, it survived in another form. For the later Athenians were always ready to describe themselves as the sons of Cecrops. This Cecrops was numbered among the imaginary pre-historic kings of Athens; he was nothing more than the fabulous ancestor of the Cecropes. But the time came when other Greek dwellers in Attica won the upper hand over the Cecropes, and brought with them the worship of Athena. It was a momentous day in the history of the land when the goddess, whose cult was already established in many other Attic places, took possession of the hill which was to be pre-eminently, and for all time, associated with her name. The Acropolis became Athenai; the folks ––whether Cecropes or Pelasgians–– who dwelled in the villages around it, on the banks of the Ilīsus and Eridănus, became Athenians. The god whom the Cecropes worshipped on the hill, Poseidon Erechtheus,was forced to give way to the goddess. Legend told that Athena and Poseidon had disputed the possession of the Acropolis, and that each had set a token there, the goddess her sacred olive-tree,the god a salt-spring. The dethroned deity was not banished; there was a conciliation, characteristic of the Greek temper, between the old and the new. Erechtheus in the shape of a snake is permitted still to live on the hill of Athena, and the oldest temple that was built for the goddess, harboured also the god. In later times Athenian "history" transformed Erechtheus into a hero, and regarded him, like Cecrops, as one of the early kings.

Athena and Poseidon on a vase painted by Amasis

There was another god who was closely associated in Attic legend with Athena, and Athens was distinguished by the high honour in which she held him. This was Hephaestus, the divine smith, the master and helper of handicraftsmen, the cunning giver of wealth. But we cannot say how far back his worship in Attica goes, or when his special feasts were instituted. It is probable that his honour grew along with the prosperity of the craftsmen. An Athenian poet calls his countrymen "sons of Hephaestus," and, according to one myth, it was from his seed that all the earth-born inhabitants of Attica were sprung. At the feast of Apaturia, in the last days of autumn, when children were admitted into the Phratries by a solemn ceremony, the fathers used to light torches at the hearth and sing a hymn to the lord of fire.

The next great step in Attic history was the union of the land.We cannot be certain at what time this union took place; it recedes beyond the beginnings of recorded history; and we can only dimly discern how it was brought about. When the lords of the Acropolis had subdued their own Cephisian plain, from Mount Parnes to the hill of Munychia, from the slopes of Hymettus to Aegaleos, they were tempted to extend their power eastward into the "Midland beyond Mount Hymettus, and subdue the southern "acté," wedge of land which ends in the lofty cape of Sunium. The completion of this conquest was possibly the first great achievement of Athens, and the second was probably the subjugation of the north-eastern plain of Marathon and the "tetrapolis." Thus the first stage in the union of Attica is the reduction of the small independent sovereignties throughout all the land, except the Eleusinian plain in the west, under the loose overlordship of Athens.

In the course of time the feeling of unity in Attica became so strong that all the smaller lordships, which formed parts of the large state, but still retained their separate political organisations,could be induced to surrender their home governments and merge themselves in a single community with a government centralised in the city of the Cephisian plain. The man of Thoricus or Aphidnae or Icaria now became a citizen of Athens and his political rights must be exercised there. The memory of this synoecism was preserved in historical times by an annual feast, and it was fitting that it should be so remembered, for it determined the whole history of Athens. From this time forward she is no longer merely the supreme city of Attica. She is neither the head of a league of partly independent states, nor yet a despotic mistress of subject-communities. She is not what Thebes is to become in Boeotia, or what Sparta is in Laconia. If she had been, and she might well have been, either of these things, her history would have been gravely altered. She is the central city of an united state; and to the people of every village in Attica belong the same political rights as to the people of Athens herself. The man of Marathon or the man of Thoricus is no longer an Attic, he is an Athenian. It is generally supposed that the synoecism was the work of one of the kings. It was undoubtedly the work of one man; but it is possible that it belongs to the period immediately succeeding the abolition of the royal power.

In after-times the Athenians thought that the hero Theseus,whom they had enrolled in the list of their early kings," was the author of the union of their country. But at the period when that union was brought about Theseus was not a national hero. He was a local god, worshipped in the Marathonian district and in the east coastlands of Attica; he had not yet won the importance which was to possess hereafter in Athenian myth and history.

SECT. 2. FOUNDATION OF THE ATHENIAN COMMONWEALTH

The early history of the Athenian constitution resembles that of most other Greek states, in the general fact that a royalty, subjected to various restrictions, passes into an aristocracy. But the details of the transition are peculiar, and the beginning of the republic seems to have been exceptionally early, The traditional names of the Attic kings who came after the hero Theseus are certainly in some cases, and, it may be, in most cases, fictitious, themost famous of them being the Neleid Codrus, who was said to