#archiveprose

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Action Potential

By Monika Narain

My friend Jessie has been dating Ben for three years now. An economics major and an English major walk into a bar during freshman orientation; they hook up once and they become inseparable. But now they’ve gotten into a big fight, and everything’s awkward, and they are apparently broken up.

Again.

At a surface level, Ben is a basic guy, who plays a lot of video games, is aggressively passionate about “impact investing,” and always cries during the Lion King. And Jessie, while I love her, is a pretty basic girl, who writes lifestyle and culture articles for the school paper, wears a lot of chunky sweaters, and also always cries during the Lion King. The two of them spend much of their evenings, weekends, and summers together, and they have seriously considered taking the “next step” post-graduation.

The two of them are terrible for each other.

Maybe it’s because Ben is too demanding, or Jessie is too loud. Maybe it’s because of all those other girls Ben keeps making out with, or that Jessie is too desperate to leave. Maybe it’s because I’ve never met two more stubborn people in my life. But for the majority of my collegiate career, I’ve been forcibly sucked into this coming-of-age soap opera, this endless saga that everyone is frankly sick of watching. Their love is a confusing flow of oscillatory moods, waves of anger immediately followed by brief moments of pure affection. And these arguments are routine, like clockwork, and they always occur in the same way.

I don’t think I’ll ever be equipped with the emotional language to fully describe the intricacy, intimacy, and inadequacy of such a couple. It’s too complex; it’s too stupid.

But let’s imagine their relationship as a dynamic system, separated by a distinct border that divides the messy region of “outside the relationship” from the even messier region of “in the relationship.” Ben, of course, as the classic dominant boyfriend, takes up a greater space “in the relationship,” and exploits a variety of controlling tactics that metaphorically push Jessie “outside the relationship” into the uncomfortable sidelines where she naturally feels upset and unappreciated. Over time, her anger and resentment towards Ben accumulate, and inevitably she reaches a point where she physically can’t take it anymore.

It’s 7:13 and Ben scowls in impatience as the basket of garlic breadsticks before him starts getting cold. He stares at his phone, then at the front door, then at the hot hostess cleaning up some annoying six-year-old’s spilled apple juice; and at that instant Jessie is staring at him from across the table.

“You’re 15 minutes late.”

Jessie sighs. She is visibly exhausted. “I’m sorry - I was finishing up a history paper and then lost track of time and then I had to get gas on the way here and yeah, it’s just been a long day.”

Ben loudly slurps his water, crunching on a piece of ice.

“So how was your day?”

“Fine. Had a midterm but I thought it went pretty well. Did some laundry. Took a nap.”

Jessie loudly slurps her water, spitting out a piece of ice.

At the start of each of these aforementioned “waves” is a trigger, a stimulus, a brief, inciting event that’s often the buildup of a series of smaller everyday annoyances.

“Have you finished editing my resume? It’s been like a week, and my dad’s been on my ass for getting a good job this summer.”

“I’m almost done, I promise! It’s just - it’s taking me a bit long to put all my comments in, and I’ve just been so busy and -”

“So you’re calling me stupid.”

“No! NO, no, no, that’s, that’s not what I’m saying at all. There’s just some areas that could use some work, you know?”

At that point a sixteen-year-old probable stoner in an “Olive Garden” button-down approaches the table. He says, not as a question but as a statement: “Hi my name is Derek Welcome to Olive Garden can I start you two off with any appetizers or drinks.”

They ignore him and keep talking. “What do you mean, ‘work’?” He makes air quotes with his fingers.

“I mean, Ben, some of the skills you write about could be framed a lot better and,” she lowers her voice, “I think you might have lied about some of the things you wrote.”

Ben scoffs. “WOW, I lied? That’s pretty ballsy coming from someone like you. Do you know how hard it is to apply for major-corporation finance jobs?

Jessie doesn’t say anything. The breadsticks are a bit stale by now, and the salad has become soggy. She looks at the clock on the wall. 7:17.

“It’s not like you’d have that much to write about anyway.”

And at that very moment, something changes in Jessie’s demeanor. All of that nice-girl energy she once performed with ease transforms into coldhearted fury, as if some switch were flipped or channel activated in her head.

What happens next is a rapid, non-reversible, all-or-nothing response:

Jessie puts her fork down. A cherry tomato from her salad falls on the floor. The kid who spilled his apple juice what feels like hours ago cranes his head in their direction.

“You know what, Ben? I’m SICK and tired of ALWAYS having to do things for you and you never accepting my opinions. It’s like, it’s like you don’t even listen to me half the time, it’s just ben ben ben ben ben ben ben 24/7! Being your girlfriend is like - a full time job, honestly, and it’s NOT fair. When are you going to start helping me with my work, get my dinner, hang out with my friends, say my outfit looks good; when does Jessie ever get anything? Sometimes, you make me so mad I just, I just, I…”

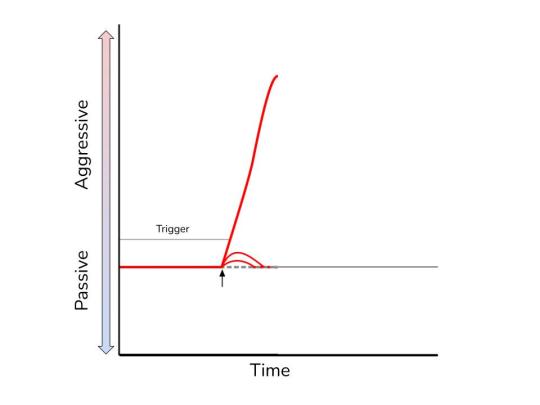

One can actually document this particular moment graphically. Over the years of observing edgy mid-adolescents in their natural element, I’ve come to observe that all young relationships are constantly fluctuating on a continuum of passivity and aggressivity, with very few (if any) consistently maintaining at the center. If we monitor points along this continuum over time, the resulting trajectory for Jessie and Ben will look something like this, beginning from the aforementioned “passive” equilibrium to a drastic rise in emotional activity that crosses into major aggression:

As is made clear, during this rising phase Jessie characteristically voices her angered sentiments in feeling excluded in attempts to normalize their imbalanced equilibrium to that of a healthier nature. And characteristically, she goes a bit too far and overshoots the monologue:

“...I just want to scream! Have you even looked at that piece of crap you sent me? You literally CAN’T. DO. SHIT. That was actually THE WORST thing I’ve ever read, and if I EVER submitted that anywhere - I honestly don’t know what I’d do to myself. And I know you flunked math, and I know your dad thinks you’re in a job, and I know ALL ABOUT Christa - did you honestly think I was that naive? God, for putting up with you as long as I have, I should get a goddamn prize, because that’s a skill way better than whatever the hell ‘synergistic analysis’ is.”

On occasion, these insults reach a point of diminishing returns.

Now, something truly remarkable occurs. Just when Jessie feels like she has power over her boyfriend, that she’s the dominating the relationship, and her verbal attacks reach their expected fortuitous conclusion, this happens:

“Well, if I’m so bad for you,” he takes a deep, calculated breath, “maybe we should break up.”

Jessie freezes. Her mouth is stuck in a halfway open and closed position. She’s getting a spam call on her phone but it feels like she can’t even get her hands to move. The entirety of the Olive Garden dining room lingers in suspense. Derek will probably tell all his friends about this when he gets more baked than a family-style lasagna.

In a hoarse whisper, she says,“Yeah. I think we should.”

They pick up their things and try to leave in separate directions before realizing there is only one exit. They don’t look at each other as they get into their cars. They forget to leave a tip.

After the fallout, there is a period of relative refractory tranquility, where there’s no fighting, no rage-drinking; they barely even talk to each other. Their dynamic can still be described as passive, but now it’s through a lens of callous indifference rather than one-sided obligatory compliance. They are now pretty much “outside the relationship,” Ben more than Jessie because he’s not as used to criticism. From anyone, really.

Despite having hit a low in their love lives, they carry on with their daily lives and pretend like they’ve never even met before. This quieter phase may be graphically represented in this manner:

But eventually, they “spontaneously” run into each other one night. He makes a joke, she laughs, even though it clearly wasn’t funny. Soon enough, they start texting and kissing and making out and before you know it they’re back to eating out of the same organic turkey sandwich and making out on the soccer bleachers. The mechanisms that have long defined their relationship - passive, active (if you know what I mean) - are seamlessly reintroduced, and things return to their default, egregiously problematic state. They seem to forget as quickly as they forgive. It makes me sick.

And the whole cycle repeats. Over and over again.

Can two people be terrible for each other, but at the same time meant for each other? I’ve always thought that this incessant emotional rollercoaster is their fatal flaw, a blatant indication of a toxic relationship. But what if this volatility is the key to their success as lovers? What if these perpetual peaks and troughs are not only a natural, but necessary part of their love, creating its foundation and subsequent continuation? What if arguing is their way of communicating with each other, and what if it’s working? And who am I to judge whatever the hell they are, when I’ve never shared an organic turkey sandwich or made out on the bleachers with anyone?

What their dynamic reveals is more than the fascinating inner workings of juvenile lust. It actually reveals a great deal about the neural mechanisms that facilitate such romantic idiocy, namely something called the action potential. This is nothing more than a temporary disruption in electrical activity, a characteristic “spike” that sends the voltage of a nerve cell from low, to high, to low, to really low, and then back to low again. This particular pattern is namely the result of the interplay between sodium and potassium ions, two like charges that move in and out of a cell based on varying thresholds of electrical activity. Such a pattern forms the basis of all neuronal communication; and, in turn, all human behavior.

0 notes

Text

forgive me

Against all odds, I hope that you will one day return. But I know that whenever you do, I will be ready to forgive. I know how it will go. You will come to me, heart in hand, and I will rip my own out to replace your missing. I will offer it with shaking arms, bleeding out from the hole in my chest, and you will look at me with pitying eyes. I will forget what you look like when you are not terrible. And you will laugh, not unkindly, never unkindly, and hold your hand out expectantly; I will wonder if you are helping me stand or taking my resolve. I will offer you both then, and you will not choose because you have always been selfish and I have always been weak. And when I am finally level with you, I will glance up quickly and you will smile then, not unkindly, never unkindly, and ask for another chance. Another chance to change, to repent, to regret. And I will hesitate, biting my lip and looking everywhere but your eyes. You will take my hands in your own, folding them in on each other and intertwining them easily with yours, and I will notice that your hands are softer than mine. And then you will tell me to look at you, and I will (because that is what I do), and there will be tears in your eyes. They will be awful and apologetic, threatening to spill over with the thought of losing the part of me that is yours, and I will cry too. Leaving splotches on your sleeves, trying desperately to wipe them away before you notice. But you will notice (because that is what you do), and you will hold my face in your hands, and you will tell me that it is okay. And you will pull me in, whispering in my hair that it was just a mistake. And I will believe you, allowing myself to deafen the alarms I have grown accustomed to. And I will look at you again, and you will smile, and I will too. I will then pull away from you in an attempt to regain my sense of balance but you will not allow it, pulling me back into your chest and wrapping your arms around my head as if you were the sole thing holding me together. So I will tell you to wait and that I need some air and that it will only be a second. And you will not listen, and you will tighten the grip you have around me, and you will move your arms down from my head and encircle them around my neck instead. No sound will come out of your mouth, nothing I can hear anyway, but if I were to look up at that second, I would see the corners of your mouth tilted upwards, not kindly, never kindly. If I were to look up, I would see the veins on your upper arm screaming with no intention of letting me go, of letting me breathe. If I were to look up, I might catch the sweat beading off your forehead in an attempt to escape the poison emitting from your pores and I might let myself believe that I am one of those drops. That I will find some way to wrestle your arms off of my neck and fill my lungs again. But I will not, so I will not be able to breathe until you allow me to (because that is what we do), which I know that you will at some point. You will never intend to silence me permanently. You will never aim to kill. Only, perhaps, to scare. To remind. So I will know that the moments I spend in your lethal embrace are only temporary, and it will be this thought that comes to mind when I look in the bathroom mirror the next morning to find a crown of blue around my neck. And in nine days, when the blue fades to yellow, and the yellow fades into a memory, I will touch the skin and flinch because it is still raw and fresh. And when you go to reach for my hand, I will flinch again, and you will become frustrated, and grab instead.

Folding them in on each other and intertwining them roughly with yours, and the only thing I will think is that your hands are softer than mine. You will yell, and I will listen, and I will apologize, and you will not. You tell me that kinder people would be more upset, and I will nod, and I will apologize again. Will offer my hands out in desperate compromise. You will look at me then, and you will shake your head. No, you will say, you are not worth it. And you will turn, and glance back once, and leave. And, against all odds, I will hope that you might one day return.

0 notes

Text

Forrest Drive

By Ethan Gurwitch

Wooden alphabet blocks sliding across a red, tiled floor—my first memory of Forrest Drive. I did not know why we were looking at houses, as our 1915 craftsman bungalow in Sanford, N.C. seemed perfect. Nonetheless, I was happy to be there. The “Red Room,” as we would soon call this seemingly ever-expanding space, was equal in size to the bungalow’s ground floor. The room, empty at the time, was the perfect play space, so we decided to knock down a stack of wood play blocks and slide them across the floor. At one end, I stood, sliding blocks to the others, who attempted to dodge them. During this newly created game, we were barefoot. So, getting hit surely meant you would break a toenail at least.

The "others" I am referring to are my sister Gracey—my “Irish Twin”— and my two cousins, Caelan and Jimmy, who were two years older and younger than I, respectively. My mother took us to this house, just two miles from the bungalow, with an exterior of chipping, tan paint in hopes of buying it at a bargain and accomplishing something on her own, while my dad was away. She told us the house was a "fixer-upper," while emphasizing this repeatedly to the seller’s realtor. I assumed this to be a ploy at reducing the asking price, $350,000. As we walked upstairs, into the hallway, equal in length to my 26-foot Rainbow Loom necklace created in middle school several years later, I ran my hands across the lawyer’s wood. The dark, outdated paneling, with its woody knots and decorative molding, was in stark contrast to the worn-down, orange, wooden floors popular in the 1950s.

As we walked past the kitchen, library, office, and dining room, into the foyer, I was awestruck, and by the look on my mom’s face, so was she. My naive nine-year-old self wondered, how could a house so large be going for this price?

At this point, my mother was a stay-at-home parent. Unlike those on Desperate Housewives, a show we would both come to love, she had a do-it-yourself mindset—doing most of the renovations with her friends while my dad worked overseas. With her experience in home remodeling, she had high hopes for what I now understand to be a dilapidated, mid-century modern mansion.

Despite her efforts, she could not get the price reduced. As we drove away, disappointment on our faces, we decided to end our home search there. That is, until the realtor called us three months later. She told us the house was not selling, and knowing my mother was interested, they decided to lower the asking price for her. She signed her name the next day, making us the proud new owners of my childhood home.

As we re-entered the foyer of our new project, moving boxes in hand, the daunting scale of the work hit us. Struck with the heavy smell of mildew, we noticed the water stains spotted across the formal living room’s ceiling. In the dining room, the Paris-themed wallpaper was worn through, exposing yellowed drywall underneath. Given the house was built in 1953, the AC could not keep up with the sweltering southern heat. In the back yard sat a 35,000-gallon swimming pool laden with cracks, weeds, and one enormous frog, which would have to be removed by hand.

Regardless of the flaws, including the mustard yellow, shag carpet installed in the early 70s, we knew we could make it work, and work we did. Our uneventful move into our home would signify the start of my mother’s many projects.

The first thing that “had to go” was the kitchen. At the time of this remodel, my mom’s friend and her two daughters—Nina and Nadia—were living with us after recently immigrating from Sweden. My mother, being the strong-headed caregiver that she was, was determined to give her friend a helping hand. Her friend, Lena, had little money and knew bits of English. In between taping up doorways and removing noxious green countertops prevalent in many homes of the area, my mother would help her friend with notecards, quizzing her on facts ranging from our first president to the past participle of the word “run.”

Though it may seem unusual, at least to me at the time, that a grown woman was learning, what I, a student at B.T. Bullock Elementary School, had been told a dozen times, Lena was trying to earn her green card. In return for helping her study, she would help my mother with the kitchen, as my dad was away in Afghanistan, and my siblings—Gracey, Jernigan, and Alexei— and I were too young to help her.

My dad, an E-6 in the U.S. Army, was gone for six months out of each year. Though I am nineteen now, he has only been my father for nine and a half years. In and out, a father and husband one day, and a man over the phone—a white landline— the next. I am reminded of his absence whenever I pass one of the many gifts he sent me, even to this day: wood dolls, stuffed animals, and other boyish things. I wonder what it is like to have a father who knows you, who raised you?

The sunset yellow cabinets were repainted a desert tan and the counters were tiled over with variegated, brown, and gray stone. Despite the impression given off by Southern Home, we later regretted this dysfunctional design choice, as tile makes for an awful baking workspace and is too difficult to clean. At the same time, we converted the tired, Parisian-themed dining room into a makeshift kitchen. Though we had no stove, we did have a waffle maker, an instant pot, and an assortment of handy, easy-to-use cooking gadgets.

After a humid, summer day, the AC barely hanging on by a thread, my mother made us breakfast for dinner—my first encounter of such a meal! The moist smell of vintage furniture that usually lingered throughout our house was replaced by sizzling sausage, a mountain of pancakes, two-dozen eggs, and Aunt Jemima syrup. Our dining table, laced with memories of dinners past, was now bursting at the seams. Gracey, Caelan, Jimmy, Jernigan, Alexei, Nina, Nadia, my mother, Lena, my uncle, and I were crowded around the buffet.

As I finished off my last flapjack, rubbing it through the last dribbles of syrup on my plate, I wished these nights—gathered around the table, with my family and friends— would never end, but end they did. The last door handles were screwed into the cabinets. The curtains, a paisley red, were hung up, regardless of their clashing with the farmhouse yellow of the kitchen. Lena, my makeshift stepmother for months on end, eventually passed The Naturalization Interview and Test. She secured a job as a bank teller for Wells Fargo and moved out.

With this, my mother’s first projects were complete.

Six and a half months later, while my brothers were in early high school, it would be time to tackle the fractured, concrete swimming pool. Around the same time, Julian, a “friend of my brothers,” came to live with us. While driving home from Davison’s Steaks, my parents saw him sitting on the side of the curb near the downtown train depot. As I heard through the fiberboard hollow core doors of my parent’s bedroom, he was kicked out for reasons unknown and needed a place to stay. Initially a temporary situation, they thought about adopting him down the line, later disclosed to me by my mother.

With my mother’s next projects in full swing, the aforementioned frog would be scooped out of the pool. And, yes picking up a Bullfrog the size of our neighbor’s small dog was strenuous and left our hands covered in a syrup-like mucus. Which would later end up in my sister’s hair.

Our goal was to finish the pool before summer. After pumping the water out of the massive pool, all that was left were mountains of leaves. Unlike those covering the surrounding trees, these leaves were brown, compacted, and reeked of sewage. The pool had all the characteristics of a swamp, including large quantities of algae and precariously aggregated flies. This would be one of the first projects I got to help on, so I was cautiously excited. With our shoes off and rakes in hand, my sister and I jumped into the shallow end of the pool. The calf-deep leaves were heavy, damp from the algae-filled water that was previously removed.

“Shut the fuck up, bitch!”

On the other side of the fence, I could see Julian running down the street with his skateboard in hand. Unaware at the time, preoccupied with a cumbersome pile… mountain, of leaves, he just fought with my parents over snake bite lip piercings he got with his stepmom’s approval, in secret. Regardless of Julian’s pugnacious attitude, he was ordered to take them out. Interestingly, I learned from my dad three days after that he had tried to convince my parents to take him to a piercer—they had obviously told him, “No.”

The pool would not take that much longer. With most of the leaves out of the way, I could see the extent of what was left to do. As far as we knew, the pool had not been used for at least a decade. The Pomeranz family, at the peak of Sanford society in the 60s, commissioned the addition of the pool. With their booming success in the international looming business, they could afford such an extravagant addition. However, much to their chagrin, the loom was phased out and replaced with speeder, modern fabric manufacturing techniques. Thus, marking the end of their business, their use of the pool, and the rest of the house for that matter.

Sitting unused for such a long time, the sea-foam blue paint covering its walls had chipped away. Hoping to complete the pool in just a few days, we would need to strip and repaint.

You have not experienced summer heat until you’ve stood inside an empty, lightly painted swimming pool in the middle of June. Sunlight, great for the garden just nearby, bounced off the rough concrete, heating it to skin blistering levels. To make the work bearable, we needed to keep a water hose running, which allowed us to walk on the surface freely.

With just a few chips of paint remaining, we worked to finish the scraping. After washing out the pool, my mom painted it a powder blue with an air painter she got from the local Rent-All down the street. Despite how grueling the renovations were, our family manual labor felt cathartic. When I think back to Forrest Drive, passing just nearby, I think of the work we did together, and of course, the time we spent gossiping over pizza and Subway after. My siblings and I now had a common thing to bitch about.

I saw my father stumble back into the wall adjacent to our front door, bracing himself against the white, bowing chair rail jutting out from the wall. Julian was the opposite of him. When I turned the corner, into the foyer, I saw my mother standing, attempting to diffuse the situation. The air was still, the calm before a storm. Reaching into her pocket, she pulled out her phone, a burgundy Motorola Razor. Before she finished dialing, she told me to go back to my room.

Wrapped in my Toy Story quilt with Woody and Buzz’s faces plastered against a cloud speckled, sky blue background, I could hear the tidbits of commotion. Splintering, as if a tree had fallen—which, did occur twice while we were leaving there: one landed on the roof and another in our backyard both while I was 16.

A few hours later, I crept down the stairs, still lacking a railing. With each creak of the floorboards, I froze. The tension in the air was heavy, but also, meeting an untimely demise was not on the day’s agenda. When I made it downstairs, back to the foyer, the weight of that afternoon hit me. Without hesitation, my eyes darted towards the doughnutted Formica door leading into the office.

The pool was complete, and Julian— “a brotha from anotha mother,” as he would say, for almost two years— was gone, picked up by his stepmom. I never asked what happened to the door. Though, it was replaced by an oak and glass pocket door.

January 2016, passing the glass pyramid in Memphis, Tennessee, we were almost to the group home where my stepcousin, Paige, was staying. My sister, my mom, and I were cramped into the blue, two-door Mini Cooper purchased just two weeks prior. A few months before, my mother learned Paige moved into a group home after being kicked out of her grandparents’ house. Before staying with them, while I was still in diapers, she lived with us.

Unconvinced the group home, located in the mountains of Missouri, was a safe place for an impressionable teenager, my mother wanted to let her move back in with us. Bumping along the gravel driveway winding around the split-level ranch, with its white columns and red brick façade, we could see the kids standing up top. “Which ones Paige,” I remember asking. Before today, I had never met, let alone seen her. After listening to Bad Romance played on the grand piano by one of the other group home girls, we loaded what little Paige owned—three pairs of jeans, a selection of tops from Justice, a purple body pillow, and three Beanie Babies—into the Mini, and head home. Apparently, from what she told me; the other girls had stolen the remainder of what she brought there.

The sleeping arrangements had all been worked out. I would take the downstairs bedroom, my brothers would be moved to the far back rooms, Gracey would stay put, and Paige would take my old room, just across from my parents. For this to work, however, the bedrooms would need a facelift.

We first started with Paige’s room. Before, the walls were a cobalt blue and the floors a faded brown with the gloss worn through, revealing the rough untreated wood underneath. To remedy this, cheaply, my mother decided to hand paint the floors. In both Paige’s and my sister’s rooms, rugs were painted onto the floors to match their new wall colors. Paige’s floors were painted cream with white daisies. Her walls were a pale turquoise. In my sister’s room, the walls were painted pink. In the center, a rectangular section of wood was painted with black and white diamonds. Around the edge, a black and pink striped border was added. My mother did both rooms by herself while attending Campbell Law School.

When it came to my room, on the sub-floor of our three-floor split level, I had the freedom to do as I saw fit. With a grey concrete floor, and a white acoustic tiled sealing, I knew the room would need a total remodel.

“Give me the phone!”

“What phone?”

From my room, connected to the Red Room by a short hallway, I could hear my mom yelling at Paige. This was just three months after she moved in, and my concrete floor was painted pumpkin orange. The ceiling tile was replaced with ice white sheetrock and the walls, the familiar cobalt blue—I realize this did not match.

My sister came through the door. “Paige stole a phone from the Temple Theater,” she told me. Her hands were around herself and her quivering lips were drawn in. Her eyes were hidden by the side of her turned-down face. She confessed to me that she knew Paige had stolen a phone and told our mother. Worried as to what her actions might have done, I consoled her. “She’s not going to kick her out,” I repeated. Gracey grew up with only brothers, and though I played Barbies and dress up with her, Paige filled the sisterly gap.

A year later, those words would come back to haunt me. Crying at the top of the stairs, Paige was standing with a bag of clothes at her feet. The day before, my mom walked into the living room, catching Paige and her boyfriend on the couch. “What if one of my children walked in here and saw you two,” she screamed. I do not know much of what happened, but that would be the last time I saw her in person.

Over the 12 years we owned that house, we poured in hours of labor and love. With the help of my mother, we built a home and memories. As I drive by, even now, I think of what my mother has created, and what we have done. Paint, pool, floors, doors, trees, family, and friends—all are a part of Forrest Drive. Though not all, both people and things, had a successful, permanent ending. I do wish the new owners would have refrained from painting the front door a seashell pink. After all, this is not the beach.

0 notes

Text

A Golden Throne of Arrogance

By Mary Elizabeth Howard

The folds of red silk come with her to the vanity. The glistening, red fabric sits on the table as she sits on the golden chair placed in front of the mirror. She unwraps the perfect square with gentle moves of her fingers to reveal the locks of braided hair inside. Two different colors tied to each other and blending together. One part completely golden, one a dark blackish-brown, and the last a mixture of the two so well-combined that it forms its own color. The blond strands are wavy and short. The blackish-brown pieces are curly and long. They are uncompromised in their natural state. It represents something. She used to know what the strands meant. Now she doesn’t know what to think, and she doesn’t know what to do with the dead keratin. She can’t throw the pieces of hair away yet.

“I didn’t know you’d kept it, it’s even still in the cloth I gave you.”

She scrunches her face up in surprise and embarrassment. Then she closes her eyes and takes a deep breath. She stands with her naked face, dripping hair, and black dress. She turns around to face him. Her golden man in his grey suit leaning against the doorway.

“What are you doing here?” she asks with defeat. “How did you find me?”

“You didn’t think I’d forget to keep tabs on my wife, did you?”

Her nose twitches in anger, and he grins.

“What are you doing here, you rotten storyteller?”

“Oh, pet names so soon. I’m thrilled.”

She narrows her eyes at him and raises her voice.

“Eres mentiroso. And you didn’t answer my questions, so fucking answer them already.”

“You know I don’t like answering questions someone already knows the answer to, amante”

“What makes you think I know the answer, Gabriel?”

“You know me, cara.” She threw her head back in frustration. He was irritating.

“Stop calling me that. Stop giving me false endearments and give me what I want.”

“You know divorce isn’t my style, and I thought you loved me, Isabella.”

“I don’t.” she said with a forced kind of certainty.

“Hmm.” He walked to where she was sitting, lifted her chin, and looked into her eyes. He was searching for something, and when he found it, he smiled. It was a devilish kind of grin and in his eyes she saw the wickedness and danger she had missed when she first met him. “Let me know when you’ve made up your mind about us. I want you home.” With that parting statement, he walked out of the room and she watched him walk away. Her gaze affixed to his strong shoulders, firm backside, and the golden glint of the ring on his hand as he walked out of her bedroom. When the front door slammed shut, she realized that he had taken the strands of their braided hair with him. He had left the red sheet and in place of their hair was the ring she had thrown at him, the match to his.

Secret never lasts His love was an illusion Her trust must be earned

0 notes

Text

Creekside

by Miranda Gershoni

Translucent green pours up and through. Teasing from my desk, the glow of the bottleneck. I’m back to seven, the walk home from school when mama took us down a different street. We roamed through shadowed trees, looking. Fossils, glass, bones, twigs for the fire. Leaves browned and feet grew and the creek sang still. Our new ritual, scouring the earth after school, treasure hungry.

Mama showed us what we couldn’t see. Raccoon skulls, pre-war milk bottles, an extra breath in the day. I was always catching up, trailing behind myself. My mind revved and tangled. Then we walked gingerly through trees. Looking for treasures below, it slowed me.

These days there is no time for slow. But past the cries of fading debts I hear you in the water near. Trapped in the flat hue of dirt, a scarlet brown filtering the sun. I reach down and pry it out. The remains of a beer bottom, soft and crooked glass patiently wed to its industrial stamp. Tiny bumps curve the edge in obedient rhythm—a Braille of better days, a half mandala that lives to tell the end.

The oyster shell sits as always. Demurring above papers, the numbers leaking out, it sits. Gold rapture waiting to be asked. Painted before your hands were dust, its shape makes mine different now. Holding it emits something new, a fresh duty somewhere far. Back then I could sink, before when flesh could be trusted. In my palm now the shell is cold. Will I ever thaw below it again? A thousand miles east from our creek, mine rushes on. Each print leaves the anatomy of place, history bleeding before me. I know she couldn’t stay here. The gold was part of it. Making new what none of us saw. The drip of stars welled in her, cavernous hunger bowed in stillness.

Molecules packed, no page left white.

So many times we’d just go. Get in the car and move till we got there. Chest dense with bass. Clanging riffs and raspy voices. Content to sit in the safety of surprise, we flew above the road like boys on bikes. From my window now they ride on, witches like us in middle school skin. On the brown glass I see it—seven two. The year your body drifted in. Always your numbers, everywhere. Saying hi from the water.

Mama tell me how. I walk with the leaves. I sit with the water. I listen to the restless finch. I look with the eyes you made, taught me to see with. What flickers on and where? How is the hard one. But you knew that.

The boys just came back around. I remember when we looped like that. Through side streets and alley gardens, grab some basil on the way. Us like paint in the hot air. Lifting from wheels down the hill, rising higher to meet the sun. Those tiny white flowers spinning out on even more impossibly delicate stems. We ride to the tip, laughing. Our sidewalks never ended.

What you knew I can see only now. Why you needed to scream. Peel and bite into avocados. Howl with James Brown in the car. Walk each street and round every corner. Take my hands and dance the floorboards in. Eat many colors. Add sesame seeds and sprouts. Try it with raspberries on your fingers. Write what’s true and burn it. Let the fire take your tears. Bring us to see the smoke. Let us be your fire. Let me be your body now. And you, my spirit. I feel you in the wind. Say it again. Tell me one more time.

0 notes

Text

I think I could love you

by Emma Huang

I think there are strands of my hair left on the glass of your bathroom shower, permanently welded into an arrangement of my resolve. And it will be anything more, nothing less than so; it is simply a cluttering of pieces, a souvenir from the softest parts of myself. And you will laugh when you see it, and I will ask you what you find so funny, and it will be this, this reminder of my existence within your own. You kiss me clean with this art of myself as the backdrop, and I think I could love you.

I think there is sugar crumbling to the hardwood some walls past. It is the result of broken sweets that are still beautiful, always beautiful, and I understand that love tastes despite. And because I am accustomed in this manner and apology is a difficult sort of thing to unlearn, I grimace. Bracing; but you hate me playfully. Lovely, you whisper, The earth needs flavor too. And so we leave them on the floor, these remnants of our mornings together, and I think I could love you.

I think there are books, my books, lined along the spine of your home, the manifestations of all that my younger self prayed she would find. The give and the take. Accumulated through the bare longing of else, you swear that we have outlived them all. Take my hand, bow to no one but resolve, smile in such that could perhaps kiss naivety silent. The chords of the music are but the lines in my books, and we dance amongst these other realities, in our own, and I think I could love you.

I think there is a flame constrained by glass and kissed by autumn atop the bedside table. You have found a routine in its ignition each evening, struck and lit and blown as if it held all of the warmth of our nights in its wax. I find that the shadows cast flickers against your easiness — illuminating depth with no threat of height. I am here, I tell you, and you are listening. Always listening. The words have long since been claimed, and I use ours to tell you I love you.

0 notes

Text

Wordle #248 Thorn

by Henry Stevens

My grandma had a farm with blackberries growing in the back fields, and every year when I was a kid, I’d get sent there with my cousins around mid-June, when the blackberry season was just starting. We hated her. My grandmother never missed a chance to say a cruel word, and she had a talent for finding what hurt the most. One time she mistook me for the neighbor’s kid and screamed at me to get out of her property. Only when she had snatched me up for a beating did she realize I lived with her.

Baking blackberry cobbler from scratch is the only sweet memory I have of those summers with her, at least the only sweet memory with her in it. We would all go out in muck boots and straw hats carrying plastic buckets to pick as many blackberries as we could find. My younger cousins would squirm under the thorns. My older cousins would reach up over them. My grandma would step on them with her boots and pull them back with her hands, and I would lean in to pick the secret berries she revealed. The berries were lustrous black, so ripe they oozed purplish juice if I squeezed them, but we left the red berries to ripen for us later. My grandmother would tell me what clever hands I had and how beautiful my berries were. Her words were as sweet as the juice.

Back at home, she was stern again. She would set us each to tasks, my younger cousins washing the blackberries in a plastic colander, my older cousins whisking by hand the sugar and flour and milk and butter, and me to sprinkle the blackberries over the batter. If we didn’t do it exactly the way she taught us, she would snap at us, asking if we were stupid and calling us lazy. She wouldn’t let any of us touch the oven. While we were preparing the cobbler, she would go out to the woodpile and split some rails to bring back and stoke the fire with. We cooked the cobbler in a cast iron dutch oven she nestled in the coals. It sat dusty grey and glowed with vines of orange, and I was terrified when she reached in and snatched it up, but the cobbler she served was golden and sweet.

My cousins slowly stopped coming with me on those summers. They started doing camps and internships, then college and jobs. When it was my turn, I cherished the freedom to escape from my grandma’s farm, and not even the cobbler could make me miss her. The year before I stopped coming, she had refused to let me eat it. She said I was getting fat. I didn’t talk to her again when I got to college.

In my junior year, when I was very lonely, I got an email telling me I had received a letter in the mailroom. It was a white envelope with her curling cursive scrawl across it. I took it back to my dorm and considered throwing it in the trash, but I decided to open it. She had never struck me as a writer, but her prose was beautiful and witty. She told me about being old and missing me and inquired about my life at college. Enclosed in the envelope was a $100 bill. She said that it was to treat myself to a nice dinner, but I spent it on library fines. I wrote back to her even though I had trouble finding an envelope and a stamp until the campus post office helped. I didn’t miss her, so I told her I missed her blackberry cobbler. She sent me another letter a week later. She enclosed a notecard with the recipe.

0 notes

Text

awakening

by Emma Huang

She was the first drag through an unfiltered cigarette… poisonous, contagious, but not too much so. Lingering on your conscience long after you should have allowed her to. And you had been good recently, so good, steering clear of the counter in the back of the store, in no fear but your own. You had run green cotton through the water multiple times daily in hopes of the smell retching out in any scent but temptation. This is okay. Hands steady, steadier than they’ve been in years. Years, years of forgotten coins and black lungs; you are eighteen and naive and this is the woman of your dreams. Who? You are nineteen soon and relentlessly unwilling to lay at night with the grappling in your hands and the hair in your eyes, refusing to bleed water for her. You are young. I am young; young, but now twenty is unusually bright, unknown crevices illuminated now by this reckoning of a woman; you are painfully aware of your blood in its efferent attempt to save you; I don’t need salvation.

So when you awoke one morning to her smoke in your lungs and her hands strangling your vices, you also find a hand pushing on the nape of your neck, allowing you finally to bow down to desire, to love – this is not discipline, never punishment. You are disgustingly accustomed to the ridges of the expectation. Of the predictable. So when you hold her edges in your soul and they are low and they are muted and they are soft, it is a wonder that the silence is not broken by the sighs lit upon your veins. It is quiet, quiet save the synchronization of both intentions; hesitation could deafen us in this moment. She raises a cigarette to your lips. You lean forward and breathe in, breathe in these chemicals of hunger, of desire; you think you could be permanently intoxicated from tonight. You look over. She is turned away from your beautiful damnation, but her ripples of warmth are still butchering the waves of your voice. Admiration in its rawest form… you are assembled before this holy art of a woman that drains fire in the wake of her touch.

You have forgotten, forgotten to breathe out. Breathe out the fumes of all that once was before, dissipate it with one hand. That was then. This is now. Fill your throat, your future with the rawness of it all instead. This is now. Considerations of perception are a ridiculous thing of the past; you love her, you have always loved her, and there is no greater truth than this smoke in your lungs.

0 notes

Text

Wordle #246 Tacit

by Henry Stevens

When Yang went out, she texted Sirui where she was going and when she would be back. She would send him a selfie in that night’s outfit, a miniskirt and top with cleavage window, a long dress with slits from ankle to waist, or, tonight, a black dress cut into skinny pieces wrapped around her thin frame. She wore a black choker with a gold bell with that dress, and black velvet gloves. Her boyfriend didn’t like clubs, dancing, or anything fun like that. He didn’t stop her from going.

Yang and her friends didn’t tell each other they were staying together when they got to the club with the shark tanks, but they didn’t part either. The tanks were huge, glowing blue water lit by hidden neon lights, with mako sharks gliding silently behind the glass, constantly searching for food, watching the warm bodies bounce on the crowded dance floor. The DJ was dropping some house that shook the water and confused the sharks, making them writhe in fantastic bursts that awed the dancers. Yang stared at a black eyed Mako as it stared back at her. A man touched her waist.

“Hey,” said the foreigner, “You want to dance?”

He was taller than most Chinese guys, at least in the south, and he had his white silk shirt unbuttoned so that his broad, hairy chest burst out, gold chains falling across it. He had a rugged arc of stubble around his jaw and dangerous, flashing eyes. He scared Yang, but not enough to frighten her, just enough to get her heartbeat up, her palms tingling. He bought her a drink and took her to dance. He smelled musky, a man scent that no cologne would make. He smelled like he went through girls like her every night, his huge hands gently guiding her body this way and that, gliding along her hips, sending her writhing around him. She forgot to dance with her friends. They didn’t come to find her either. The man asked if she wanted to find somewhere quieter. Yang shook her head.

The foreigner held her chin in two fingers, tilting her face up so he could look down into her eyes. He had such striking grey eyes. Dark hair pulled back in a pony tail. He kissed her. She let him kiss her. He disappeared into the crowd, and she wandered to the bar, to start messaging her friends on WeChat. They regrouped and went to a different club, and then a third club that night, and when they had gone to three clubs, it was early morning, and they went back home.

Her apartment was fuzzy in the morning. Sirui was asleep at his desk, the rainbow lights of his gaming rig glowing over his snoring face, his phone lying next to him, a bottle of Baijiu half empty spilled on the floor. His screen was awake, paused on the end of a Japanese porn video. It asked if he wanted to watch again. Yang reached over him and exited out of it, closing the entire website and turning off the VPN. She pulled Sirui over to their bed and lifted his cumbersome bulk up. She stripped, climbed in bed with him, and fell asleep.

0 notes

Text

Save Now?

By Helen Liu

The whispers are deafening.

White-knuckled, his hands clutch the edges of his lunch tray. Blood pounds in his ears; his cheeks flush red. Before him is a mess of milk and chicken and mushy baked beans, all over the floor, dripping down his front, slowly soaking into his frilled white shirt and shiny leather shoes.

He can feel the eyes of the entire cafeteria burning into his back. He swears he can hear his name rippling through the tables. Terrible, damning, stealing his breath and pinning him to the ground - faced with the condemnation of hundreds, how can he ever be more than a bug?

He is not offered a single tissue despite the many boxes scattered over the tables. The boy who had tripped him does not help either. Likely it was accidental - perhaps it was not. But even the slightest hint of anger is stifled completely by utter humiliation, hot and heavy. Truthfully, he barely even feels the wetness seeping into his skin.

And so Ares Langston, youngest child of the revered Langston family, stands frozen at the center of the cafeteria.

You’re a disgrace to your name, a voice sneers. He can’t tell where the voice is coming from; he doesn’t dare to lift his eyes and see who had spoken. What would your parents say if they saw you like this?

It seems an eternity before people begin to turn away, returning to their lunches and conversations. Still, nobody comes to help - nobody wants to be associated with a failure of a Langston son. Slowly, robotically, he wipes up the mess himself. Slowly, robotically, he leaves the cafeteria. And the second he rounds the corner, he breaks into a run, breaths shallow and erratic, tears welling in his eyes.

Blindly, he finds an empty classroom. Slamming the door shut, he slides down against the wall, trying to muffle the sobs tearing from his throat with hands still sticky from his lunch. Snot builds in his nose; he tastes salt on his lips. How miserable must he look right now - how disgusting.

To watch where he was going - was it that hard? Must he have chosen the busiest time of lunch to trip? And why did he just stand there for so long? He could have done something, anything, to ease the situation. Is that not what he’s been taught to do his entire life?

To his older siblings, it is second nature. If his brother had tripped, he would have easily laughed it off. If his sister had tripped, the entire cafeteria would have rushed to help her. They liked having eyes on them, relishing the attention, bending the crowds to their will.

So why, then, does he feel so helpless in front of others? Why do the gazes of his peers pierce through his very being? He has always felt foreign to them, these people he has grown up with but never really known. He has never had someone to turn to, has always been afraid of trust. And so he is a stranger in his own school, timid and skittish, craving attention but running away when others try to give it.

A meek little thing like him named after the god of war - it must be some sort of twisted joke.

His sobs warp into bitter, hysterical laughs. More than anything else, he wishes he had some kind of undo button. Something to erase all his mistakes, to wipe away his past, to give him a clean slate. Maybe he could do better, if only he had another chance. He digs his fingers into his cheeks and curls into himself, trying futilely to steady his breathing. The crushing, suffocating weight of a hundred pairs of eyes on him - will he ever be able to withstand it?

I can help you.

Ares jerks his head up and scrabbles to his feet, wiping frantically at his tears. He has made enough of a fool out of himself - others cannot see him like this. But he sees nobody in the room, nobody in the hallway. “Hello?” he whispers, but nobody responds.

Did he imagine it? With a sharp exhale, he sits back down. Now he’s hearing things on top of everything; isn’t he pathetic enough?

Your self-hatred is irritating.

He squeezes his eyes shut, clamps his hands over his ears. He must be going insane.

Open your eyes and look at me, won’t you?

Slowly, he slides open an eye.

It’s himself standing in front of him. Hair styled perfectly, posture impeccable, it wears that floral-patterned suit tossed in the back of his closet, one of many outfits he’s never been able to look good in. Yes, that’s his own face staring down at him, derision darkening its gaze and contempt twisting its lips. Confident, poised, and haughty, everything he is not.

Despite the fear rising within him, he cannot help but feel a flicker of envy.

An undo button, you said? Other-Ares steps towards him, tilting his chin up with a finger. God knows you need it.

“What are you?” Ares stammers, retreating only to find his back against the wall. “Are - are you me?”

What does it look like? Other-Ares adjusts its cuffs and settles delicately in a chair. Of course not.

Ares flinches and looks away.

But aren’t I everything you want to be? Your family would be proud if you were like this.

He shudders, hugging himself tighter.

Other-Ares scoffs and leans towards him. I said I could help you. Do you want it or not?

He wants it more than anything. But still, some part of him is hesitant - what if it’s some sort of trick? “Prove to me you’re not just a figment of my imagination,” he says, hoping he sounds stronger than he feels.

If you say yes, I’ll be able to prove it right away.

Nothing comes without a cost, his parents tell him. “What’s the price?”

Other-Ares bursts into full-body laughter, its shoulders shaking up and down as it doubles over. The price? It wipes at its eyes, gets itself back together. How do I say this - you don’t have to give me anything for me to help you.

“So it’s free?”

No. A dangerous smirk curves its mouth. Nothing’s ever free.

It’s just trying to scare him, Ares thinks. Chances are he’s just hallucinating, so why not indulge while he can? The scene at the cafeteria flashes back into his mind; he shivers, desperately trying to push the memory away. “Yes,” he blurts out. “Help me.”

Other-Ares smiles and stands, bending down to stare him in the eye. Close your eyes. It covers his face with an ice-cold hand and plunges him into darkness. Welcome to your new life.

The hand disappears. With a gasp, Ares jolts awake, blinking up at the front of the classroom. The students around him are already packing their bags; the teacher is finishing up his lesson on the board. That’s right - he’d fallen asleep in the class before lunch. It must’ve been some sort of strange dream.

There’s no sign of Other-Ares; his shirt is completely clean. With a sigh, he slides his books into his bag and stands. Head down, eyes trained on the floor a few feet in front of him, he makes his way to the cafeteria. Funny - the lunch today is chicken and beans. Habitually, he grabs a carton of milk, then makes his way to his usual table in the corner. What a coincidence it’d be if he were to trip right now.

A couple feet away, a boy sitting with his back to him suddenly stretches, extending his leg into the center aisle.

Ares freezes, breath catching in his throat.

The boy draws his leg back under his table. The students behind him mutter and move around him. For once, he barely notices. Instead, he stares at the spot a few feet in front of him, at the center of the cafeteria, where he once stood covered in his lunch. “What is this?” he whispers, barely audible.

A phantom weight on his shoulder. He jerks his head to the right to see Other-Ares, its arm around his back. Didn’t trip this time, did you? It nods towards the back corner. Go on, sit down. What are you just standing here for?

Stiffly, Ares walks over to his table, setting down his tray. “It wasn’t a dream?”

Of course not.

“I saw the future?”

I sent you back in time.

Ares takes a deep breath, forcing his hands to still in his lap.

Still don��t believe me? I can send you back again if you want. Other-Ares moves to cover his eyes, but he hurriedly pushes its hand away. “I believe you. I believe you.”

Well, I’ll be here whenever you need me. When he looks again, Other-Ares is gone.

He spends the rest of the day in a daze, oblivious to the world around him. Every five minutes he fumbles with his shirt to check if it’s still clean; every few moments he pinches himself to make sure he’s not dreaming. Every time he closes his eyes he expects to wake in his bed - wrapped in blankets and blinking at the chandelier hanging above, his nanny knocking on the door and calling for him to get up, the sound echoing through the empty manor.

Yet the day carries on as usual. He sits quietly in his classes; he walks with his head down in the halls. And when he gets home, tossing his backpack into his room and collapsing onto his couch, he finds Other-Ares waiting for him, sitting primly at the edge of his bed.

Did you enjoy your day?

“Why are you doing this?”

It tilts its head. Why not? It’s entertaining.

“This power - will I have it forever?”

You have no power.

“You know what I mean,” Ares snaps, surprising even himself. “Sorry - how long will you stay around?”

Other-Ares blinks, then grins widely. As long as I’m entertained. And as long as I can help you. I’m you, remember?

Ares takes a deep breath. “How far can you send me back?”

Just to the last time you woke up. Other-Ares points to his computer. Like a save point in a video game. Nothing before that.

A knock on the door. Panicked, Ares motions for Other-Ares to hide; it ignores him and leans back against the bed. A moment later, his nanny enters with a plate of fruit in her hands.

“Good afternoon, young master,” she greets him, setting down his snack. Ares sighs in relief - she doesn’t seem to be able to see Other-Ares. “I thought I heard you talking to someone. A friend?”

Ares flinches; Other-Ares snickers. “Just someone online,” he lies, trying to keep his eyes away from the bed.

“I’ll stop interrupting, then,” the nanny says, moving back towards the door. “Young master, I’m glad you’re getting to know more people. I may be saying too much, but being so isolated all the time can’t be good for you.”

“Thank you,” he says through gritted teeth. Other-Ares nudges his shoulder. Lonely, are you?

His nanny closes the door. With a long exhale, Ares digs the palms of his hands into his face. “Could you please just leave me alone,” he pleads. “I look like a freak talking to you. I don’t know how to deal with this - I’ll call you when I need you, is that alright?”

Other-Ares laughs, a harsh, grating sound. Ungrateful child. It’s no wonder nobody hangs around you. And yet he pushes off the bed and disappears, leaving Ares wondering if the past day has just been a delusion in his head.

The next day he wakes in a cold sweat. “Are you there?” he asks tentatively, unsure which answer he is hoping for.

Of course. Its voice is dry and sarcastic. Young master, do you need me?

Ares leans back against his pillows, trying to make sense of the possibilities swirling in his head. “No,” he breathes. “No, not yet.”

That day in history class, he is called on for a question he doesn’t have the answer to. “Didn’t you do the reading?” his teacher asks, clicking his tongue. “This is fairly simple.”

Face burning, he looks down at his feet. “Sorry.”

Waving him away, the teacher continues with his lecture, tapping his hand on the whiteboard. He knows that his classmates could care less, that at least half of them are half-asleep. And yet he cannot help the shame and embarrassment roiling in him, scalding him from within, hot pangs of discomfort shooting through his entire body.

“Take me back,” he hisses under his breath.

Other-Ares appears in front of him, one elbow on his desk, chin resting in its hand. For something as small as this? I didn’t think you were this weak.

“Just do it!”

Shrugging, it reaches forward, and Ares finds himself back in his room.

You’re going to get tired of living through these days over and over again, I’m telling you.

Ares is already out of bed and flipping through his history textbook. “That’s my problem,” he mumbles. “If I get tired, I’ll stop.”

I bet a month. Other-Ares smirks at him. One month before you stop being dramatic and learn to just deal with tiny mistakes like these.

The words sting, but it’s nothing Ares hadn’t already known. “Just go away,” he huffs, and Other-Ares disappears.

Over the next few weeks, Ares rewinds a few more times. Thrice to brush over humiliating blunders; twice to correct fumbled presentations; once to avoid bumping into his sister in the manor, who’d come home from university a couple hours before she was supposed to.

But Other-Ares was right - every time he restarts a day, he finds that he cares a little bit less. Though he remains afraid of others’ perceptions of him, the presence of a failsafe seems to dull his anxiety. So what if he holds up a lunch line fumbling for money, or if he responds awkwardly to a joke, or if his voice shakes a little in class? With just a word, none of it would have ever happened.

It gives him a strange sort of confidence, a steady warmth resting in his chest. To know his every action can be undone - why bother worrying so much?

He begins experimenting with other ways to use his power. He takes a nap on the way to a high-end restaurant, then rewinds to taste every dish on the menu. He tries out five new hairstyles, even bleaching and dyeing once. One night, exhausted and sleepy, he forgoes studying for his economics test. The next day in class, he memorizes the questions on the test, rewinds, then looks up the answers on the way to school.

“I could make a lot of money like this,” he mumbles afterward. “I’d be the best investor in the world, wouldn’t I?”

You have enough money - why bore yourself looking at charts all day?

“My parents would like it.”

For my sake and yours, impress them some other way.

Ares hesitates but lets the topic go.

That weekend, his parents request that he attend a banquet. Other-Ares gleefully critiques his outfit and posture all the way to the car. I don’t know how you’ve lasted this long. You have no idea how to act in situations like these.

“You think I’m not aware?” Ares hisses, tugging at his collar. He’s still jittery, but much less than usual. Shutting the car door in Other-Ares’s face and trying to push down his nerves, he barely manages to catch a few minutes of sleep before arriving.

“The youngest Langston!” the man at the door exclaims. “Ares, isn’t it? I spoke with your sister earlier - did you not come together?”

“Ah - um -” He forces a smile. “She decided to go ahead by herself.”

The man laughs. “Older siblings are like that. Only worrying about themselves, and forgetting about the little ones.”

The family needs to appear tightly-knit to others, his parents always warn him. “No, it’s not like that,” Ares stammers. “She - uh -”

The man puts up his hands, his brow slightly furrowed. “I joke, I joke.”

“Oh.” Ares looks away, cheeks burning. “Of course. Sorry - ah, screw it. Take me back, please.”

Blinking, the man leans in closer. “What?”

The world goes dark, and Ares wakes again in the car. Just go along with him and get inside. These formalities are tedious.

“I know, I know.” Ares walks out, and the man at the door greets him once again. “The youngest Langston! Ares, isn’t it? I spoke with your sister earlier - did you not come together?”

Ares smiles, hoping it looks more natural this time. “She decided to go ahead by herself.”

A laugh. “Older siblings are like that. Only worrying about themselves, and forgetting about the little ones.”

“Always,” Ares says, inching further into the venue. “Next time, she’d better wait for me.”

The man claps him on the back with a grin. “Well, go on inside and tell her that. Enjoy your dinner!”

Murmuring his thanks, he strides in and heads immediately towards the back table, filling a plate with food. Hopefully, nobody will pay attention to him here; he doesn’t want to deal with another rewind.

Is this what you normally do? Other-Ares appears at his side, eyeing the rest of the venue. Your sister is over there. Go say hi.

“She’s with her friends. She won’t want to be disturbed.”

Are you siblings or not? You can’t avoid her the entire evening.

“After I finish eating, then.”

He’s never liked these kinds of events. His parents want him there mostly for show - he spends most of the time as he is now, alone and in a corner. He’s supposed to talk to others, to get to know the kids his age, but he’s never bothered. Any effort on his part would be forced and fake - it’s undoubtedly the same for everyone else. He doesn't understand the way his brother and sister dance in and out of their circles, constantly managing and balancing their friendships. The very thought of it exhausts him. Are those relationships not inherently transactional?

Across the room, his sister bids goodbye to her friends and moves towards the buffet table. Other-Ares nudges him. Go talk to her.

Sighing, he complies, quickly finishing what’s left on his plate. His sister looks up, surprised, when he nears. “Ares! I didn’t know you were coming. I would’ve given you a ride.”

“No need.” He tries to smile. “How have you been?”

“Good, good! University is going well.” Eyes passing right over him, she waves at someone standing behind him. “How about you?”

A strange impulse rises within him. “Not great,” he says abruptly. “School has been hard. There’s a lot I’ve been struggling with - I wish I had someone to talk to.”

Sliding a piece of salmon onto her plate, his sister takes a few moments to respond. “Ah - did you say you weren’t doing too great? I’m sorry.” Her gaze is already moving around the room, looking for another group of people to talk with. “Listen, I have to go. Tell me if you ever want to talk, alright? I hope you feel better!” And she’s gone, leaving Ares alone once again.

Other-Ares whistles. Ouch. You two really aren’t close, are you?

“Send me back,” Ares says tonelessly, staring at his sister’s retreating figure.

Why? She barely even heard what you said.

“Just do it!”

Rolling its eyes, Other-Ares does as he says; for the third time, he awakens in the car. He pushes open the car door a little harder than he needs to, robotically greets the man at the entrance, and makes his way in, this time making a beeline for his sister.

In the middle of a conversation, she doesn’t notice he’s there until he taps her on the shoulder. Annoyance flashes across her face, but she quickly plasters on a smile. “Ares! I didn’t know you were coming. I would’ve given you a ride.”

“I’ve come to every single one of these ridiculous banquets, and you haven’t given me a ride even once,” Ares hisses. Her eyes widen; her friends mutter among themselves, staring at him with narrowed eyes. “Don’t pretend - I know you’re too busy worrying about your social image to care about your own brother.”

“What are you saying?” The shock in her voice is so satisfying. “Ares, you’re talking to your big sister! Remember your place, and remember where you are!”

“Then act like it!” he bursts out. “You’ve been at home for a week and we haven’t even talked once!”

“You say that like you haven’t been avoiding me!”

Ares laughs harshly. “Yeah, I wonder why?” Breathing heavily, he turns to Other-Areas, standing amidst the gathering crowd with a widening grin on its face. “Alright, I’m done. We can go back now.”

You’re more fun than I expected. And once again, he is back in the car.

Other-Ares taps on his shoulder from the backseat. Was that really necessary?

“Not really,” Ares says, still trying to slow his racing heartbeat. Adrenaline rushes through his veins; he feels like he could fly.

Other-Ares considers him for a few moments, then shrugs. I mean, I’m not complaining. By all means, go ahead.

The rest of the evening is as dull as usual. He pulls no more stunts and ends the day peacefully in bed, falling asleep with a slight smile on his face.

The next afternoon, sitting in front of the computer and clicking through a visual novel, he realizes something.

“The characters in this game are so shallow, aren’t they?” he says, half to himself, eyes fixed on the screen.

Yeah, video games are like that.

“Everything about them is already coded in. Their words and actions are wholly based on my choices.”

Yes. Other-Ares tilts its head. That’s how video games work.

Ares chews absentmindedly on his lip. “Then how is that any different from my life right now?”

Hmm.

“Every time I rewind, it’s as if I’m playing through a different game route. Yesterday, with the guy at the door and my sister - I knew what their reactions would be, depending on what I said.”

His gaze drifts down to his hands. “I don’t know. It makes interacting with other people feel so empty, like everything’s already scripted and predetermined.”

Go on.

“I just don’t understand why I used to be so scared,” he says quietly. “Now, everyone around me seems as simple as characters in a video game. What they think of me doesn’t matter if I can return to a save point whenever I want, right? I could do the craziest things without having to worry about any consequences.”

Sure, if you wanted to.

He skips a day of school, locking himself in his room and ignoring his nanny’s raps on the door. He mixes himself drinks from the family’s liquor shelf, getting alcohol and fruit juice all over the counter and floor. He conducts little experiments in school, trying to see how people will react to different scenarios.

In the first, he takes a girl aside after class. “I overheard your friends talking about you. They find you really annoying to be around.” It’s not even a lie. “They don’t seem like good people - I just thought you should know.” Later that day, a screaming match starts in the cafeteria, accusations and insults hurled left and right.

The second, he messes around during a lockdown drill. “I think I saw someone at the door,” he shouts in the hallway as the alarm begins blaring. “Masked and wearing all black - he might’ve been holding a gun!” Panic spreads quickly, and soon the school is plunged into chaos, half the students shoving their ways into classrooms, the other half sprinting for the exits.

The third, during a chemistry lab, he unobtrusively trips the very boy who had stuck his leg out in the cafeteria. The tray of beakers the boy had been carrying crashes to the ground, ripping gashes into his arms as he lands hard amidst the shattered glass.

“Damn,” Ares mutters under his breath, eyeing the blood beginning to drip onto the floor. “Oops.”

Other-Ares leans against the counter. You’re rewinding this, right?

“Yeah, yeah,” he says, distracted. His attention is on the faces of his classmates, their widened eyes, their hands covering their mouths in horror. His mind memorizes the way they make that tiny, hesitant step forward, knowing they should help, but how in the end they all stay back, too afraid or too repulsed or just too indifferent. “In a bit.”

One night, tipsy and sleep-deprived, he calls his parents. “Hello?” he slurs into the phone. “Mom? Dad?”

Please leave your message after the tone.

He curses and redials. “Pick up, for god’s sake! I want to talk to you. What could you be doing that’s so important?”

Please leave your message -

“Yeah, you know what?” He slams his palm into the counter, barely noticing the sting. “It was my birthday, did you know that? Nanny was the only person who remembered. You didn’t even send a text message! And you won’t pick up now!” Breathing heavily, he forces back the tears brimming in his eyes. “I’m your son, have you forgotten? I know you don’t care, but is saying a happy birthday that hard?���

Blindly, he hangs up, lowering his head into his arms and staring at the family portrait across the room. His cake sits in front of him, beautifully decorated and adorned with candles, a lone, untouched slice cut out. “Happy birthday to me,” he mumbles. “Happy birthday to me.”

He knows he shouldn’t care about things like these anymore. Normally, he doesn’t at all. The alcohol must’ve gotten to his head - he supposes it’s fine to have the occasional moment of weakness. His sticky eyelids flutter; his body grows increasingly heavy. He can feel darkness enveloping his vision, slow and enticing. He’ll just close his eyes for a few minutes, he thinks. Just a few minutes.

You’re sleeping now?

“Go away,” Ares mutters, turning his head away from Other-Ares’s figure.

Really? After sending that voicemail?

He ignores it and burrows further into his arms. A few moments later, he jerks up, heart racing. “Shit, I almost forgot.”

Other-Ares scoffs. I’m not reminding you next time.

Ares hesitates, nails digging into his palms. Maybe he isn’t as strong as he thinks he is. He really doesn’t want to relive this day, doesn’t want to deal with the false hope that will come with it. He doesn’t want to keep looking at his phone over and over, praying for a notification to pop up, wondering if maybe this year his family will remember.

And yet he cannot live a life in which he had sent a voicemail like that to his parents, so late in the night and so obviously drunk.

So, wiping away his tears and straightening his spine, he nods. “You can take me back now.”

A month later, on an evening walk in the park, a hand grabs his wrist and drags him into a thick grove of trees.

“Don’t turn around,” the voice hisses. “You look plenty rich, don’t you? Put your hands behind your head - I have a knife!”

Doing as he’s told, he casts a meaningful look at Other-Ares, leaning against the trunk of a tree in front of him. It grins, stepping towards him. Don’t want to play a little longer? What a shame.

As the robber begins to go through his pockets, taking out his phone and wallet, Other-Ares covers his eyes. Ares wakes up for the second time from his afternoon nap, rolling his shoulders and reflexively rubbing his wrist.

An evening walk doesn’t sound so attractive anymore, does it?

Ares shrugs, heading for his parent’s room. Sliding open a drawer, he retrieves a stun gun, examining it and turning it around in his hand. “Maybe I’ll try using this.”

You could just avoid the park.

Ares laughs. “I thought you liked fun things. Where’s the fun in that?”

That night, he walks the same path through the park, stun gun held firmly in hand. Soon enough, someone grabs him, takes him into the trees. “Don’t turn around! You look plenty rich, don’t you? Put your hands behind your head - I have a knife!”

The second the robber’s hand is in his pocket, Ares turns and pushes the activated stun gun into the robber’s side. With a cry, he falls, knife clattering to the ground. Huffing and kicking him away, Ares tucks his wallet back into his pocket.

“This is actually pretty strong,” he says, admiring the stun gun. He crouches next to the robber and pokes his shuddering body. “Did you really think you could get away with robbing me?”

“I’m sorry, I’m sorry,” the robber stammers, out of breath from the shock. Seeing the stark fear in his eyes, Ares feels a rush of exhilaration. He jams the stun gun into his stomach and activates it again, watching his limbs convulse as a horrifying smile grows on his face.

“You really thought you could just take my things, huh?” he repeats, thumb over the switch. “You want more?”

“No more, please no more,” the robber wheezes, curling into a ball. “I’m sorry -”

“Hey, what do you think?” He swings towards Other-Ares, baring his teeth. “In video games, bad guys like him usually get killed, right?”

Other-Ares shrugs, running its gaze over the man on the ground. Sure.

Ares flexes his fingers. “Well, if my life is just a video game? Maybe I should try it out!”

The robber begins inching away, eyes wide with panic. “Who are you talking to?” he whispers, reaching for the knife a few feet away. “You’re insane!”

The smile drops off Ares’s face instantly. Ruthlessly, he steps on the robber’s arm, snatching the knife away from his hand. “I’m not insane,” he hisses, grinding his heel into muscle. “You’re the one who tried to rob me! You deserve what’s coming - this is how it works!”

He tightens his grip on the knife and holds it over the robber, relishing in the pure terror on his face, then plunges down.

When he opens his eyes, his hands are stiff and sticky. Red soaks his shirt and spills onto the grass below him. And before him lies a torn-up body, covered in lacerations and stab wounds, barely even recognizable as human.

“Oh my god,” he breathes, trying to stand up, but a bout of lightheadedness forces him to sit back down again. “This is - this is a lot.”

Other-Ares barks a laugh. Yeah, you went a bit overboard.

Trying and failing to wipe clean his fingers, Ares shivers. “I think I’m done here,” he says faintly. “Take me back, please?”

Darkness falls. He opens his eyes once again, stretching his arms above his head, ready to push off his blankets and live through the rest of the day normally.

Instead, he feels cool night air and smells the sharp tang of blood.

“Hey, this isn’t funny,” Ares growls, turning towards Other-Ares. “Take me back.”

Darkness. He opens his eyes for the third time. His hands are still stiff and sticky.

“Seriously, take me back!” he demands. “Stop joking around!”

Other-Ares raises an eyebrow. What do you mean?

“Take me back to the afternoon! You did it last time!”

That was before you blacked out a few minutes ago.

The words take a few moments to sink in, sharp claws of horror slowly closing around his heart. “That - that didn’t count as falling asleep,” Ares says, stumbling to his feet. “I wasn’t asleep. I wasn’t asleep!”

You were unconscious.

“That doesn’t count!” He lunges towards Other-Ares; it takes a step back, eyes narrow. “Please, take me back to this afternoon. I know you can - you did it before.”

I actually can’t. You know how this works.

“Liar!” Ares shrieks, desperately trying to grab at its hands. “Take me back! Take me back! Take me back, or else I’ll -”

You’ll what? Other-Ares plucks his fingers away with a snort. Have you forgotten you have no power?

“I do! I’m the most powerful person on earth -”