#but it's really interesting to see how good educators and pedagogical practices are evolving

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

good news, OP!

in some of the pedagogical circles i move within, the big discussion around how to educate in the era of AI is... get students to do their work in class. where the educator is accessible for questions. and they can get their outline or draft done and be well on their way to knowing how to finish the essay on their own without panic-turning to AI, and without being up all night.

another strategy that's come up is more creative assessment design and more practical assignments and activities. think making a website instead of writing an essay, or having a 15minute 'interview' with your prof where you pick 3 out of 5 potential questions to answer instead of a written final exam. think in-class activities turned in for completion grades that you get to pick and choose from at the end of term to build a portfolio to write a learning reflection on.

less at-home work outside of class (but still some) and more autonomy over the learning and assessment.

most of the solutions being floated end up bringing learning back into the classroom and making it more engaging and less overwhelming for students, even if no one is necessarily referring to it exactly like that.

like... students are gonna procrastinate, and some of them (those with diagnosed or poorly managed adhd, for example) may end up waiting until the last minute no matter what the prof does. but working around "just get AI to do it" may end up being a positive disruption to higher education.

i completely understand & agree with the backlash against students using chatgpt to get degrees but some of you are out here saying "getting a degree in xyz means pulling multiple consecutive all-nighters and writing essays through debilitating migraines and having severe back pain from constantly studying at your desk and chugging energy drinks until you get a kidney stone and waking up wishing you were dead every day, and that's just part of the natural process of learning!!!" and like. umm. i don't think that any of us should have had to endure that either. like maybe the solution for stopping students from using anti-learning software depends on college institutions making the process of learning actually sustainable on the human body & mind rather than a grueling health-destroying soul-crushing endeavor

#don't get me wrong this transition is rough hahaha#and not all schools and programs are responding well#but it's really interesting to see how good educators and pedagogical practices are evolving#and trying to meet the challenge in a way that supports learners#anyway#you're correct#education shouldn't be punitive#now let's discuss the issue whereby students can't afford their education so are working part or even fulltime while going to school#and that's part of why they don't have time for their studies and put off assignments and outsource to AI#that's a more structural issue we can't even begin to solve in the classroom...#education systems#higher education#education in the era of ai#thank queue for coming

32K notes

·

View notes

Text

CAPE Network Forum Newsletter: Issue I

CAPE Network Forum Newsletter

Welcome to our first CAPE Network Forum Newsletter. CAPE program and research staff created this newsletter as a way to communicate with our network of teachers and artists, and also to connect with arts and education colleagues in other organizations.

There is an old adage about how in crisis there is opportunity. The current pandemic crisis prompted CAPE program staff to set up the CAPE Network Forum Tumblr page (https://capechicago.tumblr.com/). The Tumblr page was a response to the need to maintain the CAPE network as a vital and evolving entity engaged together in dialogue and investigation. Posts can include CAPE network thinking and debates regarding remote learning projects for students; instructional videos created for students (there are many wonderful examples up now on the Forum); photos and videos of remote learning CAPE student work; written recipes or instructions for at-home work; questions for other network members; reflections on the challenges and potential for remote learning in our communities; larger reflections about the meaning of art or education or community at this time. The response already to the Forum has been tremendous and invigorating.

The other opportunity coming out of this crisis is the launching of this newsletter. The CAPE program and research department, and the network itself, has not had a vehicle for regularly sharing information or news about our current pedagogical and aesthetic research and practices. This newsletter is that vehicle, and we will both draw from the great work of CAPE teachers, artists, and students past and present to share, as well as welcome contributions.

As Artist/Researchers, all CAPE teachers, artists, and students conduct their collaborative investigations and create their work through inquiry. They deconstruct content, form questions, and work together across artistic disciplines without knowing the end until they come to it.

In our present pandemic, schools and their external partner organizations are navigating the unprecedented terrain of remote learning. This is immensely difficult, and many are turning to overtly structured, step-by-step activities for individual students working alone that have set or predetermined results. In this way, it is known for certain what students are doing, and certainty can be comforting.

CAPE has never worked this way; we see uncertainty and the unknown as generative of learning and art making. CAPE’s questions are: can remote learning be inquiry-based and

collaborative artistically and pedagogically? Can remote learning work towards unknown results that can still be publicly shared for further dialogue and questioning? Our artistic and academic research of these questions will form the CAPE network’s response to this crisis. I also believe our response can have a larger resonance for the meaning of art, education, and community collaborations beyond the life of the pandemic.

— Scott Sikkema

Updates:

CAPE artists are likely aware that there is a relief fund grant available to individual artists under the Arts for Illinois Relief Fund (AIRF). The application portal for this grant closes Wednesday, April 8, at 5 pm: https://3arts.org/artist-relief/

Individual Chicago Public Schools submit their formal remote learning plan on Monday, April 6, and enact their plans beginning the week of April 13. Park Forest Chicago Heights District 163 teachers and administration develop formal plans April 8 and 9, working together across grades and schools by video conferencing.

Both Chicago District 299 and Park-Forest Chicago Heights District 163 are implementing remote learning plans which encompass both digital and non-digital (take-home materials), require student engagement and teacher availability (but not taking student attendance), and only assign grades that improve student standing. Classroom teachers should soon be able to share details on these plans. To support online and take-home learning, CAPE program staff have been working with schools, teachers, and artists on distribution of art materials, and instructional videos on youtube. Many schools will begin technology distribution the week of April 13, following CPS central office guidelines. Be aware that CPS has new designations of food distribution sites, which might impact material distribution as well; see https://cps.edu/OSHW/Pages/mealsites.aspx for details.

ISBE divides the remote learning day into periods of skill practice, projects, enrichment activities, and reading. CAPE arts integration work can fit into any of these categories, and CAPE teachers and artists have already demonstrated that across the CAPE Network Forum Tumblr videos. We would especially note the compatibility for arts integration in the project or enrichment categories, and it may be a good strategy for in-school partnerships to conceive CAPE remote learning within one of those categories.

To close on updates, we call attention to the ISBE website: https://www.isbe.net/Pages/covid19.aspx. State Superintendent of Education Dr. Carmen Ayala consistently posts messages that are helpful and direct. She recently announced the availability now in Spanish of ISBE’s very thorough and thought out Remote Learning Recommendations.

Tumblr Highlight:

This week's Tumblr Highlight is on CAPE teaching artist Jordan Knecht's first instructional video. See his video above and the accompanying post below. For more content from teachers and artists, please visit our Tumblr page.

Written by: Jordan Knecht

Hey everyone,

I’ve been thinking about how I’d like to approach our instructional videos. It’s been so inspiring to see how everyone is thinking about and making their own!

I have plenty of thoughts on my philosophical approach to videos, but I’m going to keep this post brief, because this post is all about brevity.

I just made my first video for class. I made it really quickly, because I’ve been feeling myself tense up with the internal anxiety of not making a video correctly: not making it up to my own standards, missing something, being awkward, etc. I decided to use this first video to pull off the bandaid real fast to get over the awkwardness and move forward. It certainly isn’t perfect, but I knew that I would spend days hemming and hawing over it if I didn’t just make the leap.

In the video, I invite my students to respond something they appreciate having around that helps them fight boredom and provides them an outlet for creativity. That invitation is extended to you all.

Here is the link to the video: https://youtu.be/jfvVcDxMoo4

CAPE Network Interview: Ayako Kato, Interviewed by Jenny Lee

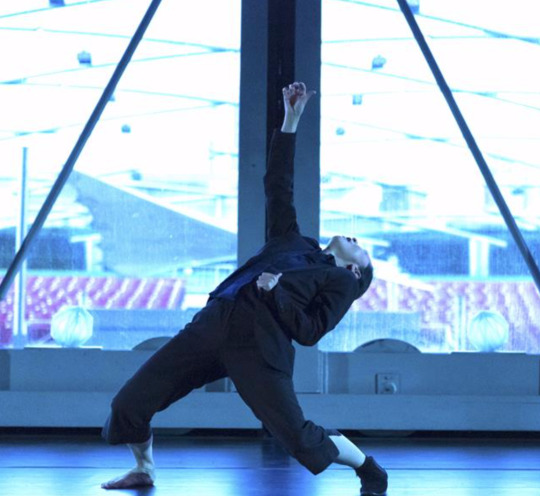

Ayako Kato is an award-winning choreographer, dancer, improviser, and educator originally from Yokohama, Japan. Since 2012, she has also been a teaching Artist/Researcher for CAPE. In 1998, she founded Ayako Kato/Art Union Humanscape, which has been producing a large number of choreographic performances in collaboration with composers, musicians, and visual artists in the US, Japan, and Europe. Initially trained in classical ballet and later modern dance, she also went on to practice Tai Chi, Noh theater dance/dramaturgy, and butoh under Kazuo Ohno, one of the butoh’s founders. Influenced by Taoism and the traditional Japanese aesthetics of "furyu," wind flow, she considers dance as an art of being which expresses "The Way" of nature within and outside ourselves. Within the CAPE network, she co-teaches with Vanessa Saucedo at Telpochcalli elementary school and with Marybel Cortes at Patrick Henry elementary school.

What has been inspiring for you during this time?

Every week since the beginning of this semester, my daughter’s drama teacher has sent us pictures. He’s always an inspiration for me. He communicates very well with us, and we start to know what’s going on in the drama class, and it raises awareness. It becomes more real.

I teach my own adult workshop for professionals and pre-professionals. When this all happened, I felt I was up against the wall. However, after I experienced my daughter’s online lesson, I was encouraged to try out one for mine. I watched a Zoom instructional video on YouTube, learned to share my screen, and figured out how to set up two cameras, one for conversation and another to capture my movement, suggested by my tech-savvy student. My musician husband set up a microphone to avoid feedback without me asking, and eventually even my daughter taught me how to use "gallery view" through Zoom. The first workshop went really well! Step by step, I found out I could do anything through Zoom! In some ways, it was better than a physical class in terms of being able to share some text closely and closely show the detailed movement of fingers and other parts of the body.

What have been some challenges and positives to remote learning?

It was difficult to hear that the schools were closed. I learned a lot about CPS guidelines: no direct communication, no text...I was not counted as an “essential” visitor, which made me sad. Then, who am I? How would I get in contact with my students?

The thing is as a teaching artist, although I try my best to guess, I don’t know how busy teachers are. I don’t know how much parents want to continue the afterschool program in this condition. I don’t know how much students are interested in continuing their artistic practice. I bet parents must be having a hard time keeping up even with students' academic homeschooling. But through my own daughter’s remote learning experiences and online lessons, I could see that when parents, students, and teachers are all together motivated, remote learning can happen. So, after the first week of setting up Seesaw Application, reflecting on only five parents out of eighteen signed up for that, I asked Vanessa if she could reach parents and encourage them to sign up again. Then, thanks to her one more push, we got eleven students/parents signed up now.

I started to see hope through Seesaw. So, with Marybel at Patrick Henry Elementary School, we started to use Seesaw as well as posting the same assignment contents on the Henry Home Page. We decided to set up the means to submit assignments in two ways: Google Drive/email and Seesaw. Again, after we posted our assignment for the second time, we started to get responses. Checking Seesaw two days ago, I noticed that if I click "See Translate" on Spanish, it becomes English. I could read the translation immediately. Then, using Google Translation, I responded in Spanish! So, I am communicating even better than I was in classrooms. I can write to parents even in Spanish. This is a great benefit and I feel magical!

It took a while for me to drop all the expectations I had in the first place when the school was closed. Letting go was important. Vanessa, Marybel and I just have to do what we can. We just hold on to even a tiny hope and find inspiration from other teachers, parents and our students who have the willingness to work together. Then, we can find ways to communicate and keep improving students' potential.

Do you have any ideas or questions about what you, your teacher partners, and students might discover or encounter regarding dance integrated teaching, learning, and/or art making during this pandemic situation?

During this Stay at Home Order, I feel more people started to do running. I see their seriousness to get through this period, maintaining their health. Those people know how the body gets weaker and stiff if they don't move. I myself once had severe pain in my sit bone. I diagnosed myself because I started to sit longer than usual. I fixed it by stretching and moving. This experience made me feel more serious about reaching students to keep them moving. What I mean is not necessarily dance, but moving your body contributes to maintaining your health. The question is what and how. Dance can give you the physically and mentally lifted state of being or the aligned flexible body with lifted feelings. Through dance, your mind and perspective open up more for creative ideas and actions.

I hope parents from the After School program notice the difference in their children when they are having dance classes twice a week versus none. Vanessa was just kindly sharing with me how students had changed through the dance class. They increased more confidence, focus, and constructiveness. I also have been seeing their improvement through not only physicality but also creativity.

Dance is very corporeal; it is an art form of and with the body. Has working and teaching remotely changed any of your perceptions of dance itself?

I have nothing other than even more affirmation on dance or the power of dance during this time! What movement/dance can do to us, the living body, is amazing!! I have been imagining people, things and elements in nature moving at this moment synchronically somewhere in the world. All the things, living things and nonliving things are moving, shifting and transforming on and even inside of the earth. During my online Zoom workshop, looking at the people moving in each different location, I felt, "Wow...this is real. Moving/Dancing together, witnessing and sensing each other who are in other locations, is amazing!" Through my recent live-streaming concert, I noticed the audience can be on the other side of the globe! Live performance cannot be beaten. Yet, I am definitely starting to experience possibilities through "virtual" yet "reality" moments of dance.

www.artunionhumanscape.net, Ayako Kato on Vimeo

Contemporary Recall

Each issue of the CAPE Network Forum Newsletter we will look back at a past example of contemporary arts practice in CAPE.

April 2nd, 2010: Chicago Arts Educators Forum Presentation:

How does our community leverage 21 st Century skills to promote art education?

Written by Mark Diaz:

In creating a workshop on exploring the pillars of 21stCentury skills, my collaborator Mike Bancroft and I looked to interdisciplinary installation art as a practice where art administrators and teaching artists could challenge their assumptions and wonderings around critical thinking, collaboration, creativity, and communication (skills listed by the national Partnership for 21stCentury Skills). Participants entered a room with no tables and chairs stacked high. At the center of the room were rope, blue tape, post-it note pads, wooden sticks, and a tinker toy set arranged without any written instructions. Instead, the instructions, sequenced by an egg timer, were verbally delivered by Mike and myself.

As participants collected in the room, Mike and I played with the tinker toys and posed questions such as “what is technology?” and “what is collaboration?” While discussing ideas about the nature of technology and qualities of collaboration, participants slowly started to play with the materials in the room and started to interact with each other. They then, on their own, began assembling random arrangements in whichever space they decide to settle in. All the materials, including the stacked chairs, were used in unexpected ways. As arrangements started to take shape and form, Mike and I posed questions about what they were making and how they were making. They began discussing the significance of their assemblages, making relationships with what they were making to larger ideas, and in relation to those idea, organizing themselves into smaller groups.

After forming groups within the larger collective, a few members from each group underwent a quick video and audio tutorial. They were sent off to take several random video clips and audio field recordings that were based on ideas that were developing from their installations. Teams reviewed these video clips and audio recordings and were asked how they could be used to embellish or enhance the physical work that was emerging in their spaces. The clips were arranged in a sequences and video were projected on to their installations. Their audios were also played within the installations.

This was an atypical art making workshop where participants were presented with materials not commonly associated with art making. Rather, participants were provided with a situation to experiment with materials in a new way and to consider use of the space in which they create their installations. Participants grappled with the formation of collaborative relationships and through intermittent, timed questions and dialogue, they synthesized concepts and ideas emerging from their projects.

Installation art practice afforded participants to create and innovate without predetermined outcomes. By engaging in critical dialogue about form, space, and meaning, participants utilized technology to enhance their projects. Through minimal yet intentional direction, they self-organized to collectively problem solve the creation of

singular art installations comprised of multiple, interlinked parts. This approach engendered multidirectional participation for educators and administrators to deconstruct and reinvent the 21stCentury skills in a way that opened up more thinking and ownership.

CAPE Program Staff:

Scott Sikkema, Education Director ([email protected]) Mark Diaz, Associate Director of Education ([email protected]) Joseph Spilberg, Associate Director of Education ([email protected]) Brandon Phouybanhdyt, Program Coordinator ([email protected]) Jenny Lee, Research Program Coordinator ([email protected])

0 notes

Text

Where Are All the Faculty in the Open Education Movement?

Open educational resources (OER) are gaining increasing popularity. And as an active member in what advocates define as the “open education movement,” I frequently hear about the growing dissatisfaction of textbook costs and pedagogical concerns among faculty about outdated course materials.

When I attend professional gatherings on open education, however, instructors like myself are often the minority. Yet open educational materials impact faculty and students alike, and many instructors are using these resources today. So why are there so few practitioners actively involved in increasing open education?

To answer this question, I have to examine my own experience with OER and its advocates. I first came into the open education field as an educator frustrated with many traditional textbooks in my discipline. Therefore, I had the simple mission of writing an openly-licensed textbook that not only addressed my students’ learning needs, but would be accessible to anyone. To me, using OER felt like a no-brainer.

That mission led me to connect with other professionals who shared the same passion and ideology—that a high-quality education should be accessible and affordable to everyone, regardless of their upbringing or background. Soon I started to attend open education conferences in order to gain a better understanding of the issue, and those in the field welcomed me with warmth and excitement.

However, I began to notice a discouraging theme at these professional gatherings: I was consistently one of the few college instructors present. Many working in open education praised me for being so involved in the movement as an educator dealing with OER on the ground. But their praises were also minced with a bit of visible surprise or even confusion about my motivation or interest in open education issues. Even more, it felt odd to listen to discussions about faculty use of OER and barriers against adoption in the classroom without a strong faculty presence in the room.

We know that many educators today are using OER. Nine percent of faculty at two- and four-year institutions used openly-licensed materials during the 2016-2017 academic year, a near double increase from the previous academic year, according to a survey by the Babson Survey Research Group. So when I ask, “why are there so few practitioners actively involved in open education?” I am not referring to OER usage in the classroom. Instead, I want to know why few faculty are driving the open education movement.

James Skidmore, associate professor and director for the Centre for German Studies at Waterloo University, is currently investigating the diffusion (or lack thereof) of open education at his university.

He argues that the lack of faculty thought leaders in open education might be partly due to what the instructor is already focused on their current role. “People who are interested in the teaching aspect of the job certainly like the notion of sharing materials,” says Skidmore.

But staying on top of innovative teaching methods and adopting new course materials is not at the center of every faculty member’s work. In some cases, Skidmore says research, publishing and other interests and professional duties presents obstacles to adopting OER—let alone advocate for it.

Skidmore explains, “For some people, it’s a question of how much time they want to put in their teaching. So typically at a research institution, faculty are told to not overdo it on the teaching. [The notion is] do enough to be good, but don’t do more than that.” Joining a movement around open education, he adds, “won’t help in securing tenure.”

Dr. Clayton Funk, senior lecturer in the Department of Arts Administration, Education and Policy at The Ohio State University echoes this sentiment: “OER are not typically counted toward research requirements, because they are seen as lacking the vetting process that comes with, for example, peer-reviewed articles.”

Many non- faculty open education advocates are aware of this enormous barrier presented by systemic policies and the tenure and promotion process. A faculty member like me, who is non- tenure or holds a teaching-intensive role, might have an easier time to participate in critical open education discussions.

But it’s important to note that at times, faculty are also at fault for sustaining these policies, buying into them, and sometimes creating them. If faculty are unhappy with the limitations that the academy enforces, they have to push for a change and not accept the status quo.

There is an even deeper social issue to explore in trying to figure how to get more faculty thought leaders in open education—the fear of sharing among faculty and advocating for this practice. Even making something as simple as syllabi visible to the public can receive pushback. For faculty nervous about public backlash and scrutiny, sharing your course materials with the world can also be intimidating.

“I know a professor who didn’t want to post materials into an open context for his teaching because he was afraid that if he made a mistake and gets caught, his reputation would be hurt,” Skidmore recalls. “The fear of sharing has been drilled early on in our careers, and faculty members are so cognizant of being rated and ranked and looked over that it’s affecting our ability to share what we know [to the public].”

I find this mindset particularly problematic for faculty members who teach at public institutions that are funded by taxpayer dollars. Faculty should feel compelled to share their work publicly and step outside the academia vacuum, while simultaneously supported by their respective institution and department to do so without reprimand. Failure to do this perpetuates the structural, social, and economic barriers that higher education is (supposedly) called to eradicate.

Communicating the Message

Knowing the challenges that exist for instructors who use OER, what can non-faculty OER advocates such as librarians, policy advocates, administrators, instructional designers, edtech professionals and others do better to appeal to faculty? Clearly communicate and evolve the message.

As Laura Killam, a nursing instructor and open education advocate at Cambrian College puts it, “It’s marketing. The textbook giants are really good at selling their products and faculty sometimes fall for it, preventing us from even wanting to delve deeper into the issue of open education.”

Yet, major textbook publishers are taking notice of the increased interest in OER, which has, among other factors, affected their profit in recent years. In response, publishers such as Cengage and MacMillan adapted their products to be more affordable, but have been justifiably accused of engaging in deceptive marketing tricks to exploit OER (ex: creating a paywall for “open content”). This is often referred to as “openwashing” or the attempt to market a product as open source when it is quite the contrary. Faculty need to be aware of these misleading messages.

Open education advocates also have to be aware of language used in discussions with faculty.

“I get nervous with calling this a movement,” says Skidmore, although he supports open education. “When you have a movement, you then start creating those people who are orthodox and those who are not. Then we get into the political questions such as ‘well, are you open enough?’ or ‘are you following all the rules of [the open education movement]?’ That is not appealing to instructors,” argues Skidmore.

Instead, Killam suggests to, “offer open education as one of several solutions to a problem that faculty have.”

Open education advocates who are not faculty should also attend discipline-specific academic conferences to spread the word about open education and create a stronger presence. The traditional textbook publishers will surely be there—why not open education advocates?

It’s equally important to highlight ways in which faculty are already engaging in open-like practices such as collaboratively curating materials or sharing their work via blog posts. This helps to normalize “openness” in academia. I also call on a push to create more space and time for faculty to develop course materials and engage in teaching development. This has to receive better recognition institutionally. The implications are critical for our students, who desire strong educators, not just researchers or scholars.

This all could speak to a “complete cultural overhaul” as Funk sees it. “But I do think it can happen over time because the students love it [open educational resources],” he goes on to say.

These social and cultural barriers are extremely challenging, but cannot be simply ignored because of their unique difficulties. The livelihood of open education hinges on tenacious efforts from all angles to combat this.

Where Are All the Faculty in the Open Education Movement? published first on https://medium.com/@GetNewDLBusiness

0 notes

Text

Coffee Break: Milken Educator Award Winner Dan Adler on What It Takes to Grow Great Teachers

When Dan Adler started his college career at Yale University, he thought he would become a chemist. When he graduated in 2007, he went into management consulting. After exploring the worlds of journalism and nonprofits, he found his calling and joined Teach For America (TFA) in 2011. Today, Adler teaches science to sixth-graders at Up Academy Leonard in Lawrence, Massachusetts.

He aspires to be the next Bill Nye and engages his students with songs, projects and even fiery cheese sticks. In November, he won the prestigious Milken Educator Award. Adler talked about his journey to become an outstanding teacher and what it will take to build a strong and diverse teacher workforce.

Are you a coffee drinker? How do you take your coffee?

I am a prolific coffee drinker. I’m not sure I know a teacher who isn’t. Either black or with a little skim milk. As much as I love Massachusetts, the “coffee regular” thing (cream and sugar) never stuck. I never got there.

What can we do to help more people like you get into science teaching?

Honestly, I wish I had a good answer.

When I graduated in molecular biophysics and biochemistry, most people I graduated with were going to grad school or med school. I was the odd duck. Teach For America made it very clear to me that our students deserved to have excellent math and science teachers. Our students deserved to have teachers with degrees in molecular biology.

It is so important that students have a teacher who knows the content. Our students deserve a teacher who is passionate and well-trained in their subject area. It is so important to student-learning that they have teachers with deep knowledge.

Something I think TFA has done so well and made clear is this aspect of the mission of teaching: No matter where you come from or what your ZIP code is, you deserve the same quality of education as anywhere else in this country.

What was your first-year teaching experience like? How did you find ways to improve?

I think I was your average train wreck of a first-year teacher. I had a great mentor.

The only professional development I focused on after my first year of teaching was classroom management. If you don’t have a foundation of routines and expectations and management skills, you can’t do the engaging lessons you want to do. I went to a multi-day professional development on tools and establishing the climate in your classroom.

I was ready for my second year.

I had a really successful second year. I became adept at classroom management. My students knew what I expected from them so they could devote their energy to learning. Now every year I get to expend my energy on other more interesting and diverse things, both in my classroom and in my own professional growth. I’m really proud of my evolution year over year as a teacher.

It’s not a sexy answer but that’s what made me an effective teacher.

The idea of teacher prep and what teachers need for day one and what they need to grow is something I have become very passionate about. It is not unique to the TFA experience to walk into a classroom and struggle your first year.

There are things we can do to make sure that years one to three aren’t more about teacher learning than student learning.

Such as?

It’s really important to have a practical pedagogical training. That means you’re not just studying theory of education. It’s important you are learning how to teach your subject area, and getting training in classroom management.

I still remember going over research that said there’s a strong link between the amount of management practice and first-year success. Once you get good at that, you can focus on content and how to get it across to students. Researchers saw a similarly strong correlation between knowledge of content strategies and success in the second year.

It’s crucial to get training in how to support language-learners and students with disabilities. You need clear and specific pedagogical tools to support whichever students come through your school doors.

So much research says it’s critical to have a year-long experience with a veteran, well-vetted mentor teacher, and to ensure there’s a strong tie between your mentor teacher and the teacher preparation program.

What about building a diverse teaching force? What are the keys there?

It’s about recruitment and retention. On the recruitment side, we need more explicit supports to bring more educators of color into the system. When I think about why I got into teaching, I think about the teachers I looked up to: my high school history and chemistry teachers.

I could understand that if you don’t see mentors who match who you are in education you might not find a lifeline in the profession. This means we need to think about how we recruit candidates whom we desperately need in the classroom, and yet are people who may not have seen that mentor in their own educational experiences.

We also need to ask ourselves: Is our pedagogy within teacher preparation culturally biased? Same goes with licensing exams. If the answer is yes, there’s bias in these exams, we need to address that.

On the retention side, when we have diverse new teachers, we can’t place all the burden of addressing diversity in students on them.

How do you make science fun?

Science is supposed to be about exploration and inquiry and discovering. I try to make my class match that.

We have a call and response in my class that goes like this: Science is not just facts…science is skills!

In my class, you need to be able to make models, do some experiments, collect and analyze data, ask questions. I’m going to push you past where you think you can understand something.

I am constantly telling my students: Did you know how important it is that scientists read and write? Otherwise you can’t communicate your findings. Let’s talk about how to read like a scientist.

I just try to make it clear to my students how important it is they do their best and that I’m always here to support them.

What’s the next challenge in building the teacher workforce we need?

The challenge becomes how do you retain those teachers? How are we making it clear how teaching can evolve year over year?

This is why I’m grateful to the Milken Foundation. This is not a lifetime achievement award.

I’ve been told: You are doing good things for kids. We want you to stay in education and convince some of your students to come into teaching and convince your early and mid-career peers to stay in and transform education.

Photo courtesy of Lawrence Public Schools.

Coffee Break: Milken Educator Award Winner Dan Adler on What It Takes to Grow Great Teachers syndicated from http://ift.tt/2i93Vhl

0 notes

Text

Overcoming barriers to learning and how to conduct a successful crit within an art classroom.

The design critique or crit is a common teaching and learning strategy within art and design education. The crit dates back to the nineteenth century and has evolved into a variety of different formats within contemporary art and design education. A number of authors have focused on the educational value, or lack thereof, for students who are assessed by a crit process and this is an on-going debate within the are and design education. This essay will consider existing literature and highlight the purpose of a crit whilst considering the boundaries within a group art crit and how to overcome these boundaries.

The first section of this essay will outline the purpose of a crit, when they work well and give a strong indication of why they are so pervasive. As well as supporting students to develop and learn more about themselves and their art practice. The crit is a pedagogical approach used extensively in art and design. Within a crit students are expected communicate their design intent and enter into a discussion of their work with peers and tutors.

‘Crits are the sharing of a practice and an opportunity for a practitioner to discuss their work, articulate what they have done in their work to their peers, and for those peers to then input into the further development of that work.’ (Blair 2013:20).

Crits are used for a number of reasons and can not only help students with their work in progress but help teachers with assessing and tutoring students and their work. However, I believe that the most fundamental part of an art crit is gaining critical distance on the work presented. ‘The main purpose of a crit is to enable an artist to gain critical distance from their emerging work.’ (Hunter 2013:20). In order to identify the educational opportunities within the crit environment each component will be identified and discussed in terms of application and scope. These components are: timing, participants, formality, duration, audience, feedback, purpose and location.

There are two common timings when a crit can be used within the educational process, this can be at an interim stage, and during final assessment (Doidge et al: 2000). The interim crit would be more informal and involves a dialogue between tutor and student based on progress. This is a formative activity and is centred on guiding and supporting the student within their practice (Dannels: 2005). The interim crit is focused on process and developing the learner within the professional field of practice. Using the crit as a final assessment will involve a summative mark being given to the work. This crit tends to be more formal and often focuses more on the end product rather than the process.

There are two parties who receive the crit: individual and group (Cennamo & Brandt, 2012). Individual is the most common form of crit, where a single individual has their work critiqued by their tutor and peers. In this context the student is expected to communicate their intentions of the work through visual or oral communication. The group crit can be used for group projects, this is beneficial where the studio teaching hours may not be sufficient to allow individual crits on a regular timetabled basis (Schrand & Eliason, 2012). However, a drawback of this technique is that it can reduce the amount of feedback each student receives, but can relieve the stress of the students in terms of presenting their work to a group (Cennamo et al, 2011).

The formality of a crit is usually in an informal manner or as part of a formal assessment process within an art and design programme. An informal approach can be a supportive opportunity for the student (Blair, 2007). In a more formal setting the students report anxiety and nervousness as well as the difficulty remembering the feedback they receive. (McCarthy, 2011). Therefore recording the group crits a really useful tool for students to re-visit at a later date and take notes. Alison James from the London College of fashion advises a way of easing students into public speaking is: ‘break them into groups, get them to work with and then present to each other one to one, then to the group, and then to the larger group. That makes them realise that presenting is not too scary and gives them opportunity to practice.’

A crit can vary in duration; it can last from five minutes to 50 minutes per student. Flynn (2005) illustrates the issues with a five minute crit: ‘ I felt that the pin-up crits were a bit rushed and when I failed one project it lasted less than five minutes.’ Those that go on for a longer period of time encounter the opposite issue, whereby students struggle with the duration and find themselves struggling what to say and loose interest in what one another are saying about the work. There is little to no evidence for an objectively correct length of time a crit should be, it can be inferred that students need an opportunity to receive sufficient feedback.

Another component of a crit is the audience who provide the critique and feedback on the work presented. There are three different groups to consider when it comes to the audience, the are the students, the tutor and external members. Students providing feedback to there peers are a key aspect in the development of professional norms within art and design. The expectation is that students gain further insight into their own work by reflecting on how their peers have approached similar problems. ‘There is always a sense that we are creating meaning. One of the great things about critique is that it is a constructive and creative process and that the people engaged in it are creating something as well. It doesn’t have a physical form; nonetheless, it’s something that involves invention, imagination and creativity. (Hamlyn, 2013). A crit can facilitate exchange, knowledge transfer and peer learning, students learn from each other. The crit exposes them to very different types of work and ways of working, and new ways of thinking about art. For some students it can be a way to identify meaning within their own work that they didn’t see beforehand. However, in some cases students can dominate the crit and with this you can get into ‘master readings’, where a student interprets the work to such a high degree that for everyone else there seems nothing left to say. Furthermore, a student or tutor could cause further anxiety through the use of jargon and specialist language. ‘Sometimes when students are talking about work or writing their academic essays, they think that they have to adopt a certain kind of voice; that they need to sound academic for example. But it is important to speak in plain English do that everyone understands’ (James, 2013).

The tutors within the crit process serve the role of deign mentor and expert as they expected to give feedback and guidance to the students, they are essentially acting as the master, passing on a tactic knowledge of the discipline through a series of feedback sessions. Within the process of a crit the teacher holds a considerable influence over the students’ own perceptions of their work, sometimes this can guide and other times confuse students both presenting and giving feedback. In some cases the tutor can be the dominant part of the crit, it is the tutors responsibility to listen to the students and embrace all kinds of interpretations, encourage the students creativity and not their own. ‘The more I teach the more I realise that actually being invisible is probably the best thing you can do. I don’t mean that you should extract yourself from the teaching but more that some of the best teaching is where you are creating a situation for people to discover for themselves what they learn. Then because they feel that they are doing it themselves they take ownership for it’ (Hamyln, 2013).

In the case of external participants are present they may be experts in the field, community members, or others with an interest in the project. The guests are to bring their expertise and professional perspective to the crit and give the students a sort of ‘real-life’ perspective on their work. They can provide students with a unique insight that the students may not have previously considered. However, larger crits can cause additional anxiety for learners and in particular can cause issues with fellow students being unable to participate as they may be unable to hear the feedback that their peers receive (Blair, 2007).

Location is often a factor that is taken for granted; Blair (2007) highlights the difficulty with hearing when participating within larger crits. Cennamo et al. (2011) point to different formats such as desks, studios and space. When the student is behind a desk, it can feel more formal and this could trigger further anxiety. However, when a crit is taking place in a circle, (Karl Rodgers theory) anxiety can be less and discussion can be more open and honest.

Students within the art and design discipline seek feedback and critique of their work in order to improve ad respond. ‘All feedback is useful to some degree, but for me, the best feedback points out a problem and offers some sort of solution.’ (Dannels et al., 2011:106). Students need to have a clear grasp of the value of feedback, when receiving and giving. However, the difficulties faced within an art and design crit is that most of the time the feedback is verbal and within conversation so can be hard for the students to remember all the feedback they receive, some students may be too interested in their own work that they do not give good feedback to their peers and so a way to overcome these barriers could be to record the crit and share with the group at the end. A specific student could write down key feedback for each student and then there is written feedback for all students. however, this could put the ‘scribe’ under pressure to write a lot down in a short period of time and have the worry of missing something important.

Finally, the purpose of the crit needs to be explained to students beforehand, so that they can make the best contribution to the crit possible. In order to give and receive ‘good’ feedback, structure can help the students understand the purpose of a crit. Therefore setting ground rules can be a useful tool to help ease anxiety for all parties of the crit. Obvious ones would be: be polite and be considerate to one another’s work and feedback. There is no right or wrong answer in terms of feedback. In some cases, students present the work and then peers ask questions and give feedback at the end, or students present their work whilst being asked questions throughout. Setting rules and structure to the crit ‘helps give the students more control, take ownership of their learning and allows them to figure out what they can use the crit as a useful learning tool.’ (Lencovic, 2013:46) It also gives them the experience of how to set up and run crits for themselves, which is vital for maintaining artistic practice after education and in further education.

In conclusion this paper has discussed the role of a crit within an art and design education programme and the key components to be considered when implementing this approach. The barriers to a crit have been highlighted and advisories on how to overcome these barriers have been discussed. ‘The crit holds the potential to be a valuable educational approach provided it adapts to modern learning and teaching approaches as well as evolving technology’ (Healy, 2016:15). Furthermore the crit can build a sense of community within the department and amongst students. Emerging artist need to support one another. That community of peers will sustain them, particularly through the difficult times. Day (2013) suggests that peer-to-peer sharing of information and support is incredibly important. And inspiration of the crit is to engender and improve that and build a community that eventually becomes self-supporting.

0 notes

Text

Coffee Break: Milken Educator Award Winner Dan Adler on What It Takes to Grow Great Teachers

When Dan Adler started his college career at Yale University, he thought he would become a chemist. When he graduated in 2007, he went into management consulting. After exploring the worlds of journalism and nonprofits, he found his calling and joined Teach For America (TFA) in 2011. Today, Adler teaches science to sixth-graders at Up Academy Leonard in Lawrence, Massachusetts.

He aspires to be the next Bill Nye and engages his students with songs, projects and even fiery cheese sticks. In November, he won the prestigious Milken Educator Award. Adler talked about his journey to become an outstanding teacher and what it will take to build a strong and diverse teacher workforce.

Are you a coffee drinker? How do you take your coffee?

I am a prolific coffee drinker. I’m not sure I know a teacher who isn’t. Either black or with a little skim milk. As much as I love Massachusetts, the “coffee regular” thing (cream and sugar) never stuck. I never got there.

What can we do to help more people like you get into science teaching?

Honestly, I wish I had a good answer.

When I graduated in molecular biophysics and biochemistry, most people I graduated with were going to grad school or med school. I was the odd duck. Teach For America made it very clear to me that our students deserved to have excellent math and science teachers. Our students deserved to have teachers with degrees in molecular biology.

It is so important that students have a teacher who knows the content. Our students deserve a teacher who is passionate and well-trained in their subject area. It is so important to student-learning that they have teachers with deep knowledge.

Something I think TFA has done so well and made clear is this aspect of the mission of teaching: No matter where you come from or what your ZIP code is, you deserve the same quality of education as anywhere else in this country.

What was your first-year teaching experience like? How did you find ways to improve?

I think I was your average train wreck of a first-year teacher. I had a great mentor.

The only professional development I focused on after my first year of teaching was classroom management. If you don’t have a foundation of routines and expectations and management skills, you can’t do the engaging lessons you want to do. I went to a multi-day professional development on tools and establishing the climate in your classroom.

I was ready for my second year.

I had a really successful second year. I became adept at classroom management. My students knew what I expected from them so they could devote their energy to learning. Now every year I get to expend my energy on other more interesting and diverse things, both in my classroom and in my own professional growth. I’m really proud of my evolution year over year as a teacher.

It’s not a sexy answer but that’s what made me an effective teacher.

The idea of teacher prep and what teachers need for day one and what they need to grow is something I have become very passionate about. It is not unique to the TFA experience to walk into a classroom and struggle your first year.

There are things we can do to make sure that years one to three aren’t more about teacher learning than student learning.

Such as?

It’s really important to have a practical pedagogical training. That means you’re not just studying theory of education. It’s important you are learning how to teach your subject area, and getting training in classroom management.

I still remember going over research that said there’s a strong link between the amount of management practice and first-year success. Once you get good at that, you can focus on content and how to get it across to students. Researchers saw a similarly strong correlation between knowledge of content strategies and success in the second year.

It’s crucial to get training in how to support language-learners and students with disabilities. You need clear and specific pedagogical tools to support whichever students come through your school doors.

So much research says it’s critical to have a year-long experience with a veteran, well-vetted mentor teacher, and to ensure there’s a strong tie between your mentor teacher and the teacher preparation program.

What about building a diverse teaching force? What are the keys there?

It’s about recruitment and retention. On the recruitment side, we need more explicit supports to bring more educators of color into the system. When I think about why I got into teaching, I think about the teachers I looked up to: my high school history and chemistry teachers.

I could understand that if you don’t see mentors who match who you are in education you might not find a lifeline in the profession. This means we need to think about how we recruit candidates whom we desperately need in the classroom, and yet are people who may not have seen that mentor in their own educational experiences.

We also need to ask ourselves: Is our pedagogy within teacher preparation culturally biased? Same goes with licensing exams. If the answer is yes, there’s bias in these exams, we need to address that.

On the retention side, when we have diverse new teachers, we can’t place all the burden of addressing diversity in students on them.

How do you make science fun?

Science is supposed to be about exploration and inquiry and discovering. I try to make my class match that.

We have a call and response in my class that goes like this: Science is not just facts…science is skills!

In my class, you need to be able to make models, do some experiments, collect and analyze data, ask questions. I’m going to push you past where you think you can understand something.

I am constantly telling my students: Did you know how important it is that scientists read and write? Otherwise you can’t communicate your findings. Let’s talk about how to read like a scientist.

I just try to make it clear to my students how important it is they do their best and that I’m always here to support them.

What’s the next challenge in building the teacher workforce we need?

The challenge becomes how do you retain those teachers? How are we making it clear how teaching can evolve year over year?

This is why I’m grateful to the Milken Foundation. This is not a lifetime achievement award.

I’ve been told: You are doing good things for kids. We want you to stay in education and convince some of your students to come into teaching and convince your early and mid-career peers to stay in and transform education.

Photo courtesy of Lawrence Public Schools.

Coffee Break: Milken Educator Award Winner Dan Adler on What It Takes to Grow Great Teachers syndicated from http://ift.tt/2i93Vhl

0 notes

Text

Coffee Break: Milken Educator Award Winner Dan Adler on What It Takes to Grow Great Teachers

When Dan Adler started his college career at Yale University, he thought he would become a chemist. When he graduated in 2007, he went into management consulting. After exploring the worlds of journalism and nonprofits, he found his calling and joined Teach For America (TFA) in 2011. Today, Adler teaches science to sixth-graders at Up Academy Leonard in Lawrence, Massachusetts.

He aspires to be the next Bill Nye and engages his students with songs, projects and even fiery cheese sticks. In November, he won the prestigious Milken Educator Award. Adler talked about his journey to become an outstanding teacher and what it will take to build a strong and diverse teacher workforce.

Are you a coffee drinker? How do you take your coffee?

I am a prolific coffee drinker. I’m not sure I know a teacher who isn’t. Either black or with a little skim milk. As much as I love Massachusetts, the “coffee regular” thing (cream and sugar) never stuck. I never got there.

What can we do to help more people like you get into science teaching?

Honestly, I wish I had a good answer.

When I graduated in molecular biophysics and biochemistry, most people I graduated with were going to grad school or med school. I was the odd duck. Teach For America made it very clear to me that our students deserved to have excellent math and science teachers. Our students deserved to have teachers with degrees in molecular biology.

It is so important that students have a teacher who knows the content. Our students deserve a teacher who is passionate and well-trained in their subject area. It is so important to student-learning that they have teachers with deep knowledge.

Something I think TFA has done so well and made clear is this aspect of the mission of teaching: No matter where you come from or what your ZIP code is, you deserve the same quality of education as anywhere else in this country.

What was your first-year teaching experience like? How did you find ways to improve?

I think I was your average train wreck of a first-year teacher. I had a great mentor.

The only professional development I focused on after my first year of teaching was classroom management. If you don’t have a foundation of routines and expectations and management skills, you can’t do the engaging lessons you want to do. I went to a multi-day professional development on tools and establishing the climate in your classroom.

I was ready for my second year.

I had a really successful second year. I became adept at classroom management. My students knew what I expected from them so they could devote their energy to learning. Now every year I get to expend my energy on other more interesting and diverse things, both in my classroom and in my own professional growth. I’m really proud of my evolution year over year as a teacher.

It’s not a sexy answer but that’s what made me an effective teacher.

The idea of teacher prep and what teachers need for day one and what they need to grow is something I have become very passionate about. It is not unique to the TFA experience to walk into a classroom and struggle your first year.

There are things we can do to make sure that years one to three aren’t more about teacher learning than student learning.

Such as?

It’s really important to have a practical pedagogical training. That means you’re not just studying theory of education. It’s important you are learning how to teach your subject area, and getting training in classroom management.

I still remember going over research that said there’s a strong link between the amount of management practice and first-year success. Once you get good at that, you can focus on content and how to get it across to students. Researchers saw a similarly strong correlation between knowledge of content strategies and success in the second year.

It’s crucial to get training in how to support language-learners and students with disabilities. You need clear and specific pedagogical tools to support whichever students come through your school doors.

So much research says it’s critical to have a year-long experience with a veteran, well-vetted mentor teacher, and to ensure there’s a strong tie between your mentor teacher and the teacher preparation program.

What about building a diverse teaching force? What are the keys there?

It’s about recruitment and retention. On the recruitment side, we need more explicit supports to bring more educators of color into the system. When I think about why I got into teaching, I think about the teachers I looked up to: my high school history and chemistry teachers.

I could understand that if you don’t see mentors who match who you are in education you might not find a lifeline in the profession. This means we need to think about how we recruit candidates whom we desperately need in the classroom, and yet are people who may not have seen that mentor in their own educational experiences.

We also need to ask ourselves: Is our pedagogy within teacher preparation culturally biased? Same goes with licensing exams. If the answer is yes, there’s bias in these exams, we need to address that.

On the retention side, when we have diverse new teachers, we can’t place all the burden of addressing diversity in students on them.

How do you make science fun?

Science is supposed to be about exploration and inquiry and discovering. I try to make my class match that.

We have a call and response in my class that goes like this: Science is not just facts…science is skills!

In my class, you need to be able to make models, do some experiments, collect and analyze data, ask questions. I’m going to push you past where you think you can understand something.

I am constantly telling my students: Did you know how important it is that scientists read and write? Otherwise you can’t communicate your findings. Let’s talk about how to read like a scientist.

I just try to make it clear to my students how important it is they do their best and that I’m always here to support them.

What’s the next challenge in building the teacher workforce we need?

The challenge becomes how do you retain those teachers? How are we making it clear how teaching can evolve year over year?

This is why I’m grateful to the Milken Foundation. This is not a lifetime achievement award.

I’ve been told: You are doing good things for kids. We want you to stay in education and convince some of your students to come into teaching and convince your early and mid-career peers to stay in and transform education.

Photo courtesy of Lawrence Public Schools.

Coffee Break: Milken Educator Award Winner Dan Adler on What It Takes to Grow Great Teachers syndicated from http://ift.tt/2i93Vhl

0 notes

Text

Coffee Break: Milken Educator Award Winner Dan Adler on What It Takes to Grow Great Teachers

When Dan Adler started his college career at Yale University, he thought he would become a chemist. When he graduated in 2007, he went into management consulting. After exploring the worlds of journalism and nonprofits, he found his calling and joined Teach For America (TFA) in 2011. Today, Adler teaches science to sixth-graders at Up Academy Leonard in Lawrence, Massachusetts.

He aspires to be the next Bill Nye and engages his students with songs, projects and even fiery cheese sticks. In November, he won the prestigious Milken Educator Award. Adler talked about his journey to become an outstanding teacher and what it will take to build a strong and diverse teacher workforce.

Are you a coffee drinker? How do you take your coffee?

I am a prolific coffee drinker. I’m not sure I know a teacher who isn’t. Either black or with a little skim milk. As much as I love Massachusetts, the “coffee regular” thing (cream and sugar) never stuck. I never got there.

What can we do to help more people like you get into science teaching?

Honestly, I wish I had a good answer.

When I graduated in molecular biophysics and biochemistry, most people I graduated with were going to grad school or med school. I was the odd duck. Teach For America made it very clear to me that our students deserved to have excellent math and science teachers. Our students deserved to have teachers with degrees in molecular biology.

It is so important that students have a teacher who knows the content. Our students deserve a teacher who is passionate and well-trained in their subject area. It is so important to student-learning that they have teachers with deep knowledge.

Something I think TFA has done so well and made clear is this aspect of the mission of teaching: No matter where you come from or what your ZIP code is, you deserve the same quality of education as anywhere else in this country.

What was your first-year teaching experience like? How did you find ways to improve?

I think I was your average train wreck of a first-year teacher. I had a great mentor.

The only professional development I focused on after my first year of teaching was classroom management. If you don’t have a foundation of routines and expectations and management skills, you can’t do the engaging lessons you want to do. I went to a multi-day professional development on tools and establishing the climate in your classroom.

I was ready for my second year.

I had a really successful second year. I became adept at classroom management. My students knew what I expected from them so they could devote their energy to learning. Now every year I get to expend my energy on other more interesting and diverse things, both in my classroom and in my own professional growth. I’m really proud of my evolution year over year as a teacher.

It’s not a sexy answer but that’s what made me an effective teacher.

The idea of teacher prep and what teachers need for day one and what they need to grow is something I have become very passionate about. It is not unique to the TFA experience to walk into a classroom and struggle your first year.

There are things we can do to make sure that years one to three aren’t more about teacher learning than student learning.

Such as?

It’s really important to have a practical pedagogical training. That means you’re not just studying theory of education. It’s important you are learning how to teach your subject area, and getting training in classroom management.

I still remember going over research that said there’s a strong link between the amount of management practice and first-year success. Once you get good at that, you can focus on content and how to get it across to students. Researchers saw a similarly strong correlation between knowledge of content strategies and success in the second year.

It’s crucial to get training in how to support language-learners and students with disabilities. You need clear and specific pedagogical tools to support whichever students come through your school doors.

So much research says it’s critical to have a year-long experience with a veteran, well-vetted mentor teacher, and to ensure there’s a strong tie between your mentor teacher and the teacher preparation program.

What about building a diverse teaching force? What are the keys there?

It’s about recruitment and retention. On the recruitment side, we need more explicit supports to bring more educators of color into the system. When I think about why I got into teaching, I think about the teachers I looked up to: my high school history and chemistry teachers.

I could understand that if you don’t see mentors who match who you are in education you might not find a lifeline in the profession. This means we need to think about how we recruit candidates whom we desperately need in the classroom, and yet are people who may not have seen that mentor in their own educational experiences.

We also need to ask ourselves: Is our pedagogy within teacher preparation culturally biased? Same goes with licensing exams. If the answer is yes, there’s bias in these exams, we need to address that.

On the retention side, when we have diverse new teachers, we can’t place all the burden of addressing diversity in students on them.

How do you make science fun?

Science is supposed to be about exploration and inquiry and discovering. I try to make my class match that.

We have a call and response in my class that goes like this: Science is not just facts…science is skills!

In my class, you need to be able to make models, do some experiments, collect and analyze data, ask questions. I’m going to push you past where you think you can understand something.

I am constantly telling my students: Did you know how important it is that scientists read and write? Otherwise you can’t communicate your findings. Let’s talk about how to read like a scientist.

I just try to make it clear to my students how important it is they do their best and that I’m always here to support them.

What’s the next challenge in building the teacher workforce we need?

The challenge becomes how do you retain those teachers? How are we making it clear how teaching can evolve year over year?

This is why I’m grateful to the Milken Foundation. This is not a lifetime achievement award.

I’ve been told: You are doing good things for kids. We want you to stay in education and convince some of your students to come into teaching and convince your early and mid-career peers to stay in and transform education.

Photo courtesy of Lawrence Public Schools.

Coffee Break: Milken Educator Award Winner Dan Adler on What It Takes to Grow Great Teachers syndicated from http://ift.tt/2i93Vhl

0 notes

Text

Coffee Break: Milken Educator Award Winner Dan Adler on What It Takes to Grow Great Teachers

When Dan Adler started his college career at Yale University, he thought he would become a chemist. When he graduated in 2007, he went into management consulting. After exploring the worlds of journalism and nonprofits, he found his calling and joined Teach For America (TFA) in 2011. Today, Adler teaches science to sixth-graders at Up Academy Leonard in Lawrence, Massachusetts.

He aspires to be the next Bill Nye and engages his students with songs, projects and even fiery cheese sticks. In November, he won the prestigious Milken Educator Award. Adler talked about his journey to become an outstanding teacher and what it will take to build a strong and diverse teacher workforce.

Are you a coffee drinker? How do you take your coffee?

I am a prolific coffee drinker. I’m not sure I know a teacher who isn’t. Either black or with a little skim milk. As much as I love Massachusetts, the “coffee regular” thing (cream and sugar) never stuck. I never got there.

What can we do to help more people like you get into science teaching?

Honestly, I wish I had a good answer.

When I graduated in molecular biophysics and biochemistry, most people I graduated with were going to grad school or med school. I was the odd duck. Teach For America made it very clear to me that our students deserved to have excellent math and science teachers. Our students deserved to have teachers with degrees in molecular biology.

It is so important that students have a teacher who knows the content. Our students deserve a teacher who is passionate and well-trained in their subject area. It is so important to student-learning that they have teachers with deep knowledge.

Something I think TFA has done so well and made clear is this aspect of the mission of teaching: No matter where you come from or what your ZIP code is, you deserve the same quality of education as anywhere else in this country.

What was your first-year teaching experience like? How did you find ways to improve?

I think I was your average train wreck of a first-year teacher. I had a great mentor.

The only professional development I focused on after my first year of teaching was classroom management. If you don’t have a foundation of routines and expectations and management skills, you can’t do the engaging lessons you want to do. I went to a multi-day professional development on tools and establishing the climate in your classroom.

I was ready for my second year.

I had a really successful second year. I became adept at classroom management. My students knew what I expected from them so they could devote their energy to learning. Now every year I get to expend my energy on other more interesting and diverse things, both in my classroom and in my own professional growth. I’m really proud of my evolution year over year as a teacher.

It’s not a sexy answer but that’s what made me an effective teacher.

The idea of teacher prep and what teachers need for day one and what they need to grow is something I have become very passionate about. It is not unique to the TFA experience to walk into a classroom and struggle your first year.

There are things we can do to make sure that years one to three aren’t more about teacher learning than student learning.

Such as?

It’s really important to have a practical pedagogical training. That means you’re not just studying theory of education. It’s important you are learning how to teach your subject area, and getting training in classroom management.

I still remember going over research that said there’s a strong link between the amount of management practice and first-year success. Once you get good at that, you can focus on content and how to get it across to students. Researchers saw a similarly strong correlation between knowledge of content strategies and success in the second year.

It’s crucial to get training in how to support language-learners and students with disabilities. You need clear and specific pedagogical tools to support whichever students come through your school doors.

So much research says it’s critical to have a year-long experience with a veteran, well-vetted mentor teacher, and to ensure there’s a strong tie between your mentor teacher and the teacher preparation program.

What about building a diverse teaching force? What are the keys there?

It’s about recruitment and retention. On the recruitment side, we need more explicit supports to bring more educators of color into the system. When I think about why I got into teaching, I think about the teachers I looked up to: my high school history and chemistry teachers.

I could understand that if you don’t see mentors who match who you are in education you might not find a lifeline in the profession. This means we need to think about how we recruit candidates whom we desperately need in the classroom, and yet are people who may not have seen that mentor in their own educational experiences.

We also need to ask ourselves: Is our pedagogy within teacher preparation culturally biased? Same goes with licensing exams. If the answer is yes, there’s bias in these exams, we need to address that.

On the retention side, when we have diverse new teachers, we can’t place all the burden of addressing diversity in students on them.

How do you make science fun?

Science is supposed to be about exploration and inquiry and discovering. I try to make my class match that.

We have a call and response in my class that goes like this: Science is not just facts…science is skills!

In my class, you need to be able to make models, do some experiments, collect and analyze data, ask questions. I’m going to push you past where you think you can understand something.

I am constantly telling my students: Did you know how important it is that scientists read and write? Otherwise you can’t communicate your findings. Let’s talk about how to read like a scientist.

I just try to make it clear to my students how important it is they do their best and that I’m always here to support them.

What’s the next challenge in building the teacher workforce we need?

The challenge becomes how do you retain those teachers? How are we making it clear how teaching can evolve year over year?

This is why I’m grateful to the Milken Foundation. This is not a lifetime achievement award.

I’ve been told: You are doing good things for kids. We want you to stay in education and convince some of your students to come into teaching and convince your early and mid-career peers to stay in and transform education.

Photo courtesy of Lawrence Public Schools.

Coffee Break: Milken Educator Award Winner Dan Adler on What It Takes to Grow Great Teachers syndicated from http://ift.tt/2i93Vhl

0 notes

Text

Coffee Break: Milken Educator Award Winner Dan Adler on What It Takes to Grow Great Teachers

When Dan Adler started his college career at Yale University, he thought he would become a chemist. When he graduated in 2007, he went into management consulting. After exploring the worlds of journalism and nonprofits, he found his calling and joined Teach For America (TFA) in 2011. Today, Adler teaches science to sixth-graders at Up Academy Leonard in Lawrence, Massachusetts.

He aspires to be the next Bill Nye and engages his students with songs, projects and even fiery cheese sticks. In November, he won the prestigious Milken Educator Award. Adler talked about his journey to become an outstanding teacher and what it will take to build a strong and diverse teacher workforce.

Are you a coffee drinker? How do you take your coffee?

I am a prolific coffee drinker. I’m not sure I know a teacher who isn’t. Either black or with a little skim milk. As much as I love Massachusetts, the “coffee regular” thing (cream and sugar) never stuck. I never got there.

What can we do to help more people like you get into science teaching?

Honestly, I wish I had a good answer.

When I graduated in molecular biophysics and biochemistry, most people I graduated with were going to grad school or med school. I was the odd duck. Teach For America made it very clear to me that our students deserved to have excellent math and science teachers. Our students deserved to have teachers with degrees in molecular biology.

It is so important that students have a teacher who knows the content. Our students deserve a teacher who is passionate and well-trained in their subject area. It is so important to student-learning that they have teachers with deep knowledge.

Something I think TFA has done so well and made clear is this aspect of the mission of teaching: No matter where you come from or what your ZIP code is, you deserve the same quality of education as anywhere else in this country.

What was your first-year teaching experience like? How did you find ways to improve?

I think I was your average train wreck of a first-year teacher. I had a great mentor.