#caching more seeds than a squirrel

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Be the mycorrhizae you wish to see in the world.

#my brain and heart are very full from all the folks in the native plant community right now#plus i got to wear my witch coat and drank way too much coffee today#rambling into the void#little ghost on the prairie#caching more seeds than a squirrel

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Month 10 - Leafbare

Prev | First | Next

Branchbark was sure that he was being punished. Russetfrond had sent him out hunting with Yarrowshade of all cats at least five times since he’d been made deputy. He had been assured that it was simply a logistical decision, but the situation felt too uncomfortable to be pure coincidence. On the other paw, Russetfrond wasn’t exactly fond of Yarrowshade so the choice might have had more to do with Yarrowshade than it did with him.

Yarrowshade, for his part, had been taking it well, it seemed. If Branchbark hadn’t known any better, he might not have guessed that Yarrowshade was grieving at all. As they roved the territory looking for prey, he smiled and laughed and answered all of Barleypaw’s questions in a bright and playful manner. Branchbark wasn’t sure, but that didn’t feel exactly… healthy.

“Great catch, kid!” Yarrowshade purred as Barleypaw returned with a sparrow hanging from her jaws. “You’re getting really good at that.”

“Fanks,” she beamed, tail swishing idly. Yarrowshade began to dig a hole in the remnants of snow to cache the bird in and Branchbark’s vision fogged as he watched the motion.

He had helped lay Nightfrost to rest that night. Beside Songdust and Pantherhaze, he had carved a hole in the cold hard earth down hill from the camp where the rosemary grew in the spring and countless Clanmates had been buried. The entire time, his throat had been thickly choked with guilt. If he had been faster, if he had gone out sooner or braved the snow storm the day before, if he had been smarter about which patches he checked-- Despite the futility of it, his mind raced to find something he could have done to avert the tragedy.

He found himself going through the same list of ‘what if’s now, only getting pulled out of his thoughts by the sound of Yarrowshade’s voice.

“Branchbark…? Hello?”

He snapped to attention and smiled out of habit. “Yes? I’m here!”

“Oh, that’s a relief,” Yarrowshade chuckled. “For a second I was like ‘where did he go?!’” He made a show of scanning the area as if Branchbark had disappeared and Barleypaw laughed in the most adorable manner. Branchbark blushed but was happy to play along with the joke for her sake.

Still, it was weird to see Yarrowshade being so goofy already. Wasn’t he hurting? He realized suddenly that Yarrowshade had been talking again and he had no idea what had been said.

Barleypaw was nodding. “I wanna see if there are any cardinals around! I’ve lost some of my feathers and I need new ones so I can stay brave.”

“Good idea,” Yarrowshade said. “Lead the way, Barley-girl! I’m right behind you.” Barleypaw nodded and bounded off through the snow. Yarrowshade followed close behind but Branchbark trailed them more slowly. He just couldn’t seem to focus today.

Yarrowshade caught a few rodents and Barleypaw caught another sparrow but Branchbark fumbled the squirrel he had spotted. Yarrowshade had laughed it off and told him it was fine but he knew it wasn’t. It wasn’t fine. He could have been smarter, faster, better. He could have found the horsetail in time. He could have-

A flicker of movement caught his attention and pulled him from his thoughts with a jerk.

Yarrowshade was crouched next to Barleypaw, both of them intently watching a bright red cardinal that was fluttering its wings and searching for seeds among the frost-firm grass. Yarrowshade was the perfect mentor, correcting her posture and whispering words of encouragement, but that wasn’t what drew Branchbark’s eye. A large, russet shape in the grass shifted, two black tipped ears alert and forward, beady yellow eyes fixed tightly on the two oblivious cats hunting a few meters away.

Branchbark was running before he realized. A loud warning hiss tore from his throat as he launched himself towards the fox, and it wheeled to face him fur puffing up in fright. It opened its mouth and let out a warbling scream and Branchbark arched his back and growled in response.

“Stay here,” he heard Yarrowshade tell Barleypaw. Then, the older tom carefully stalked up to flank the fox with Branchbark.

The fox seemed young, probably born that spring if he had to guess, and it was thin beneath its winter coat. If they were lucky, the fox would decide they weren’t worth the energy to fight and leave instead. Branchbark hissed again, edging closer, and Yarrowshade hopped forward with a few swipes of his claws. The fox screamed again, skittering backward, then lunged at Yarrowshade, jaws snapping.

Branchbark’s heart skipped a beat - he couldn’t let anything else happen to Yarrowshade on his watch. Hissing he leapt forward to bat at the fox’s face.

“Wait!” Yarrowshade yelled too late.

Branchbark’s claws hooked into its nose and it wailed in pain. Twisting, it snapped at him with sharp teeth and a lance of burning pain shot up his leg as it managed to catch his foot in its mouth and pull. Blood sprayed across the grass, the tang of its scent striking his tongue, and he hissed, trying to bash it over the face with his other paw.

Yarrowshade ducked under him and lunged, sinking his teeth into the fox’s neck. The smell of blood doubled and the fox released him with a yelping, frightened scream. Yarrowshade let it go and it tumbled away panting heavily as crimson bloomed down the front of its chest. It cursed in vulpish, looking over the red spatters on the ground, then fled with clumsy pawsteps.

Branchbark sat back with a hiss of pain and looked at his leg, giving the wound a few careful licks. Despite the pain of it, the wound seemed mostly superficial, which he thanked StarClan for. Adrenaline pumped through him, giving him a giddy lightness in his stomach.

“What were you thinking?” Yarrowshade snapped, his muzzle slick and dark with fox blood. Branchbark wilted. That wasn’t the reaction he had been expecting.

“I was trying to save you,” he mumbled.

“I didn’t need saving!” said Yarrowshade. “It was giving a warning bite, we could have driven it off without a fight.”

“I… I’m sorry,” Branchbark said, realizing that Yarrowshade was right. “I just… I didn’t want you to get hurt.”

“So you got hurt instead,” Yarrowshade glared. Branchbark had no argument.

“Are you okay?” Barleypaw asked, slowly creeping up behind them. Her big, bat-like ears carefully lifted from where they had been pressed against her head and her big blue eyes were wide with fright. Quickly, Yarrowshade tried to groom the blood from his muzzle before she saw.

“Yeah,” he said, “yeah, I’ll be fine.”

“Barley, dear,” Yarrowshade said, putting effort into sounding more gentle, “could you walk Branchbark back to camp to see Sagetooth please? I’ll collect the prey we caught and meet you there.”

“Will you be alright?” she asked, “W-will that thing come back?”

“The fox?” he looked over his shoulder to see where it had disappeared and then back to her, “No, it’s probably going to be gone for a while, if it survives. I’ll be just fine.” He smiled and she relaxed, but Branchbark could see something strained underneath his grin.

“Now go on,” Yarrowshade continued, tone turning stern when he looked at Branchbark. “Get your leg seen to.”

Branchbark nodded. “Yeah… I will. I’m sorry, again.”

Yarrowshade’s jaw clenched but he kept his smile. “I don’t want your apologies.”

Bile rising in his throat, Branchbark nodded again and turned to leave. Barleypaw walked beside him, worriedly eyeing his leg every few steps. He walked silently, trudging in his building guilt. He didn’t know how to make things right with Yarrowshade. He wasn’t sure if he ever could.

“Does it hurt?” Barleypaw asked eventually.

“A little bit,” he said, and that wasn’t entirely true. It was constant and stinging against the cold winter air, but he had grown used to it by now and it wasn’t the worst wound he’d ever received.

“I think you were very brave,” she whispered wide eyed.

“Thank you,” he said with a bashful laugh, “but I was more foolish than brave. If I had listened to Yarrowshade I probably wouldn’t have gotten hurt.”

“Why didn’t you?”

What a question. He hummed for a moment before answering, “It’s my fault that Nightfrost died. I wanted to try and make it up to him and I wasn’t thinking clearly.”

Barleypaw was quiet for a bit. “I thought it was Papa’s fault.”

“What?” He looked down at her with a quirk of his head.

“He went and got sick and so he couldn’t find the right plants. Sagetooth was really mad at him.”

“It’s not his fault,” Branchbark shook his head. “He didn’t try to get sick. Sometimes bad things just happen.”

“Then why is it your fault?” she asked.

“I wasn’t fast enough,” he shrugged. “If I’d been faster she might have survived.”

“That doesn’t make any sense,” she frowned. “If it's not Papa’s fault then it's not your fault either. Sometimes bad things just happen.”

Branchbark almost laughed. “Well I guess I can’t argue with that,” he said, feeling sheepish. How had she bested his guilt so quickly? He had a feeling he was going to feel bad about what happened for a long time, but perhaps he could let go of the idea that he was uniquely to blame. He just hoped Yarrowshade felt the same.

UPDATES: - Branchbark is injured saving Yarrowshade from a fox!

#clan gen#clangen#warrior cats#warriors#warrior cats oc#warriors oc#clangen oc#clan gen oc#Yarrowshade#Branchbark#Leafbare#clangenrising#Barleybee

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this story from The New Yorker:

Our poor memories can seem mystifying, especially when you consider animals. This time of year, many species collect and cache food to stave off winter starvation, sometimes from pilfering competitors. So-called larder hoarders typically keep their troves in a single location: last year, a California exterminator found seven hundred pounds of acorns in a client’s wall deposited there by woodpeckers. In contrast, scatter hoarders—including some chickadees, jays, tits, titmice, nuthatches, and nutcrackers—distribute what they gather over a wide area. Grey squirrels use smell to help them find their buried acorns. But many scatter hoarders rely largely on spatial memory.

People first noticed scatter hoarding by 1720 or even earlier. It’s come under serious investigation, however, only in the past century. Scientists now know that birds’ brains can contain elephantine powers of recollection. Some birds can store, or cache, tens or even hundreds of thousands of morsels in trees, or in or on the ground, and retrieve a good portion of them. In 1951, a Swedish ornithologist named P. O. Swanberg reported on Eurasian nutcrackers: over the course of a single autumn, he saw each bird make some eight thousand caches. That winter, the birds dug through the snow to retrieve their stored food. Swanberg examined the excavation holes the birds had left behind and found nutshells in nearly ninety per cent of them—an indication that there had been few fruitless efforts.

In the late nineteen-seventies, researchers at Oxford buried sunflower seeds just ten centimetres from where marsh tits had buried their own morsels. Over the following days, the bird-buried seeds disappeared significantly faster than those the scientists had buried, suggesting that the birds had precise memories of their cache locations. In 1992, other scientists reported that birds known as Clark’s nutcrackers could recall, with better-than-chance accuracy, where they’d buried seeds more than nine months earlier.

Vladimir Pravosudov began studying food caching as an undergraduate at Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) State University. “I’m a big believer in just watching animals,” he told me. Above the Arctic Circle, he’d spend hours a day with binoculars and a stopwatch, observing willow and Siberian tits; he found that they could cache food as frequently as twice a minute. Extrapolating, he estimated that they could store as many as half a million bits of food each year. He grew fascinated with the question of how and why birds had evolved to be “caching machines.”

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Piñon Pine - The Indians Own Tree

When I section-hiked the PCT from Tehachapi to Walker Pass several Mays ago, as we neared the northern end of that trip we took a lunch break one day under a grove of piñon pines. As we reached into our pack for our usual lunch of cheese, rye crackers, and salami, we began to notice that the forest floor was littered with pine nuts. While some had become food for rodents, squirrels, and other foraging animals since dropping to the ground the prior autumn, most were so very edible. Soon we were each on our hands and knees collecting cones and harvesting their delectable contents ($29 a pound at our local co-op). I ate my fill and packed an empty bag with more nuts which I brought home with me when I left the trail. This is David Foscue’s story of the pine nut.

David Foscue

An Evolutionary Feat

Piñons are coveted for their nutitious seeds. One pound of seeds may contain 3,000 calories. The pine nuts were collected by Indians as stores for the winter. Listen again to Muir: “This is undoubtably the more important food-tree on the Sierra, and furnishes the Mono, Carson, and Walker River Indians with more and better nuts than all the other species together. It is the Indian’s own tree, and many a white many they have killed for cutting it down.”

A diligent collector in the prime collecting time can gather up to seventy pounds of the seeds. Humans, of course, are not the only beneficiaries of the piñon’s largess. Pine nuts are a favorite of many animals from the piñon jay to the pack rat — it is reported that over forty pounds of nuts may be found in a pack rat’s cache. The wide popularity of piñon nuts is a matter of survival, for the seeds of the piñon lack wings and depend on animals for distribution.

The piñon of the Sierras is single-needled pine. It is a mutation of the piñon found further east on which the needles appear in bunches of two. The two-needled piñon is subject to infestation by the piñon spindle gall midge which appears to have evolved with the tree. The insect lays its eggs on the flat leaves, when they hatch the larvae crawl into the crotch between paired needles. The irritation caused by the tiny larvae simulates the plant to grow tissue forming a gall over the larval wound. The gall covers the wound but it also protects the enclosed larvae.

The gall midge evolved to inhabit the single-needled piñon which lack the needle crotches to shelter the larvae. According to Ronald Lanner, the single-needle piñon developed from the twin-needled variety but “one of the potential needle sites is suppressed by the … mutation. Our gall midge neutralizes the mutation. The feeding of the larvae suppresses the needle-suppression mechanism, allowing both of the potential needles to develop, though they reach only a fraction of their full length. The needles are galled and the larvae grow up in the same type of needle-crotch home as those in … two needled pines.” Needles at unaffected locations on the tree remain single.

Kit Carson, John C. Frémont and the Piñon Nut

The piñon played a supporting role in two dramas that have become part of the lore of the PCT. One involved “The Pathfinder,” John C. Frémont, extraordinary adventurer and the first Republican presidential candidate. The other tale involves the ill-fated Donner party.

Frémont, and his scout, Kit Carson, led the first recorded winter crossing of the Sierras. What Frémont expected to take a week became an ordeal of five weeks. As they faced the Sierras their supplies were running low. Fortunately Indians supplied them with pine nuts! On January 24, 1844, Frémont wrote:

A man was discovered running towards the camp as we were about to start this morning, who proved to be an Indian of rather advanced age–a sort of forlorn hope, who seemed to have been worked up into the resolution of visiting the strangers who were passing through the country. He seized the hand of the first man he met as he came up, out of breath, and held on, as if to assure himself of protection. He brought with him, in a little skin bag, a few pounds of the seeds of a pine-tree … . We purchased them all from him.

The Donner Party - Rescued by Pine Nuts?

George Donner’s group was not as successful in its attempt to cross the Sierras two winters later. In a snow storm, the party reached what is now known as Donner Lake in early November 1846. Attempts to reach the pass failed and the party returned to the lake and settled in. Although many of their animals froze providing unexpected food, their provisions were soon exhausted and the new settlers faced slow starvation.

On December 16 a group of fifteen left the lake in an attempt to cross the mountains for help. Using the same term Frémont applied to the old Indian who first provided him piñon nuts, they called themselves the “Forlorn Hope Party.” Death reduced the group to seven. As we now know, the dead sustained the living.

The forlorn and depleted party finally came to an Indian village on January 10. The Indians provided acorn bread to the party but the group was so weakened their strength could not be restored. The leader, William Eddy, became sick on the bread. Donner’s Daughter, Eliza, writes how Eddy regained his strength:

… the chief with much difficulty procured for Mr. Eddy, a gill of pine nuts which the latter found so nutritious that the following morning, on resuming travel, he was able to walk without support.

Eddy walked fifteen miles that day to a small settlement where he was able to organize a party to rescue the other six surviving members of Forlorn Hope. Eventually three rescue parties, including one led by Eddy, were organized to return to Donner Lake. Forty-six members of the Donner party were rescued. Forty-two did not make it. The toll surely would have been greater but for the pine nuts given by the Indians to Eddy.

Think about the Donner party the next time you sprinkle piñon pine nuts on your salad.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ultimate Guide to Squirrel Removal

Squirrels: More Than Just Furry Neighbors

Before we jump into the nitty-gritty of squirrel removal, let's take a moment to appreciate these incredible creatures. Squirrels, with their fluffy tails and agile antics, are a common sight in our neighborhoods and parks. They play a vital role in maintaining the ecosystem by spreading seeds and keeping insect populations in check. However, when they start causing trouble in your attic or garden, it's time to take action.

Squirrels are notorious for sneaking into our homes. Keep an eye out for telltale signs like chewed wires, gnawed furniture, or strange scratching noises coming from your attic.

If your garden looks like a war zone with half-eaten veggies and uprooted plants, you might have a squirrel problem. They can be quite the green thumbs, but not in a way you'd appreciate. Squirrels are hoarders by nature. If you find caches of nuts, seeds, or acorns stashed away in unexpected places, you're dealing with furry thieves.

The Hazards of Squirrel Infestations

Squirrels can carry diseases, and their droppings are a breeding ground for harmful bacteria. Ignoring an infestation can put your family's health at risk. From chewing through wires to creating cozy nests in your insulation, squirrels can wreak havoc on your home, leading to costly repairs.

DIY Squirrel Removal Methods

One way to tackle the issue is by blocking their entry points. Identify potential openings in your house and seal them up with materials like steel wool or mesh.

Using motion-activated lights, sprinklers, or even placing predator decoys in your garden can discourage squirrels from making themselves at home. Whip up some homemade squirrel repellents using ingredients like cayenne pepper, vinegar, or peppermint oil. Spray these around your garden or attic to keep the critters at bay.

When to Call in the Pros

If your squirrel problem has escalated, it's time to bring in the experts. Squirrel control professionals have the knowledge and tools to remove squirrels safely.

If you're looking for a more humane approach, consider live trapping. These traps allow you to capture the squirrels and release them back into the wild. Squirrels often use overhanging branches as launchpads to your home. Trim tree branches away from your house to limit their access. Ensure that your trash cans have secure lids to prevent squirrels from rummaging through your garbage for tasty treats.

Invest in squirrel-proof bird feeders if you're a bird lover. These contraptions are designed to keep squirrels from raiding the feeders.

When it comes to removing squirrels, there's a moral debate. Some argue for relocation, while others opt for euthanasia. We'll explore the pros and cons of each.

Deciding whether to take matters into your own hands or hire professionals can be a moral dilemma as well. We'll discuss the ethical aspects of both options.

Conclusion: Living in Harmony

In the grand scheme of things, squirrels are just trying to survive and thrive like the rest of us. While their presence in our homes can be a nuisance, it's crucial to approach squirrel removal with empathy and responsibility. Whether you choose DIY methods or seek professional help, remember to prioritize the well-being of these furry neighbors. With the ultimate guide to squirrel removal in your toolkit, you can find that sweet spot where humans and squirrels coexist peacefully. Happy squirrel watching!

0 notes

Text

The Early Glaciocene: 90 million years post-establishment

Last of a Legacy: The Skragg

It is a brief warm spell in the Early Glaciocene, as summer draws near in the forested taigas of Westerna. In this short period of warmth, less than two months before the winter comes again, many plants-- especially conifers, and highly-derived hardy stonefruit trees that adapted to protect their seeds with hard nut-like fruit casings, take advantage of this fleeting respite from the cold by producing their seeds en masse, where they will remain dormant, spread by animals, until favorable conditions come that allow them to sprout.

It is in these taigas that a small, unassuming creature is hard at work: spending the short summer frantically hoarding seeds, nuts, and whatever fruit and plant matter it can stash away in its burrows, before the cold weather sets in. Resembling a somewhat oversized squirrel, unremarkable save perhaps for the two prominent incisors that aid in peeling off the hard outer layers of seeds, this hurried hoarder carries a far greater significance than it would have at first glance: it is the skragg (Procynosciurus ultimatum), the last extant species of rabbacoon, and the only member of its once-diverse family to survive the coming of the Glaciocene.

Rabbacoons, relatives of the jerryboas and the boingos, were one of the first lineages to emerge during the end of the Early Rodentocene, where, as generalist omnivores, they thrived as jacks of all trades, eating almost anything, while squizzels specialized on fruit, hamtelopes on grass and ferrats on meat. Their success, however, was short lived, as their partial specialization on each niche led to them being outcompeted by full specialists on those niches, and as other omnivores such as badgebears, ratbats and bumbaas began crowding them out, they were pressured into odd, unusual niches at the end of the Therocene, such as the wakkoons, which became arboreal herbivores, or the bandipoos, which exploited the droppings of bramboo-eating herbivores.

But with the coming of the Glaciocene, even these odd lineages are long since gone. The skragg is truly alone now in the tree of life, surviving solely by its specialized diet of hard seeds that few other creatures its size can manage. While its burrows are occasionally unearthed by ungulopes, which help themselves to the larders of seeds, the skragg is otherwise uncontested in this niche. Able to store large quantities of food in its cheek pouches, it makes trip after trip to its burrow for days on end, stacking up a massive storage that can last it through the long winter.

It is also during this time that the skraggs breed, when food is plentiful and climates are warm. Females, however, are rather devious when it comes to stashing: as they will need extra nourishment to raise their pups on milk, they are known to seduce males with their breeding pheromones and willingly enter their burrows--only with the intention of raiding their larders and making away with their hard-earned stash. This behavior has encouraged some males to become more creative to avoid robberies: they stash food into multiple locations to avoid a total loss if one cache is breached, either by rivals or larger animals.

Once the ice comes, the skraggs enter a state of torpor. While able to sleep off long periods of time, they are not true hibernators, and thus wake up every few days to feed. This is where their stashes come into play, where they slowly feed off their stored seeds over the cold season, and while in the relatively milder autumn and summer it can venture from its burrow to pick off its other stashes, by winter it is forced to remain in its burrow: and any unlucky individual with a storage shortage risks starvation as the cold weather persists.

The rabbacoons, once diverse and widespread, have been whittled down to a single species by the pressures of competitors and later a changing climate. The sole survivor and last heir to the lineage survives on solely by its extreme adaptations in a new age and era-- and even now faces an uncertain future for the fate of its entire clade.

▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey. Saw your "ask me abt corvids". Gimme a lecture on bluejays pls I love those funky lil asshats

My primary interest lies in crows, branching out heavily into magpies (they’d probably be my favourite corvid if any lived near me) and ravens, with bluejays as the irrepressibly stupid cousin-in-law that I, the Crow Witch, know only through those awkward family reunions where you chat about the weather and pretend not to know that Uncle Fred has a nasty habit of stealing ritual stones from cemeteries, yknow?

Having said that:

Blue jays are one of the most noisy and territorial breeds of corvid, more so than crows and even magpies. They will fight pretty much anything with a face, and the feeling is mutual--despite the fact that blue jays rarely eat any other birds, most species will respond with immediate aggression if a blue jay gets too close. Probably for good reason, as they’re notorious nest thieves (especially preferring to hijack robins’ nests if they can manage it). They’re known for being raucously loud and pushy, yes, but blue jays can also be downright sneaky when they want to. Stealth home invasions and subsequent habitation of other birds’ nests are a popular alternative among jays to doing the hard work of building their own place.

Jays are also alleged to appreciate shiny objects, snatching and carrying them off (though probably not hoarding or collecting them). However, it’s hard to find credible sources on this, and given that the widespread understanding of magpies as doing the same was recently demonstrated to be false, I would hesitate to put too much stock in the idea without further research. Then again: young corvids are the delinquent hoodlums of the bird world, everyone knows this, and it’s far from implausible that particularly daring young jays would take an interest in flashy things that catch their attention. Corvids are, after all, curious creatures.

What blue jays do, without question, actually hoard are nuts and seeds. They parallel squirrels for their tendency to hide their food away for later, and like squirrels, they often just straight-up don’t come back for it. This has led to initiatives like this Santa-Cruz research effort to use the local jays for reforesting purposes to combat fire scars. Jays are actually much more efficient reforesters than squirrels and other nut-hoarding mammals, since they tend to hide their foodstuffs in highly dispersed locations, whereas squirrels and chipmunks typically have only a few hoards located close to their home tree. Also, multiple studies have shown that jays will only select perfectly viable seeds to take to their cache--any acorns or seeds that have been tainted with rot or infestation are left lying on the forest floor. (tw for discussion of animal death in that particular link, though)

Also! Yes, jays are known for their raspy loud cry, but like other corvids, they have a vast repertoire of other sounds and a strong capacity for mimicry. They’re often known to imitate the sounds of their more common predators, making up for their slow flight patterns (which render them easy midair targets to hawks) by tricking local birds into thinking they’re dangerous!

anyway corvids are cool, blue jays are valid, and thank you so much for swinging by with this ask, friend

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus

By the USFWS, in the Public Domain

Etymology: Naked Nostrils

First Described By: Wied-Neuwied, 1841

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Australaves, Eufalconimorphae, Psittacopasserae, Passeriformes, Eupasseres, Passeri, Euoscines, Corvides, Corvoidea, Corvidae, Cyanocoracinae

Status: Extant, Vulnerable

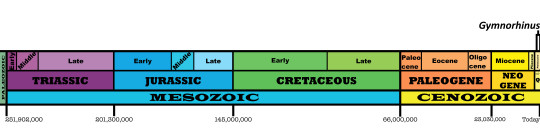

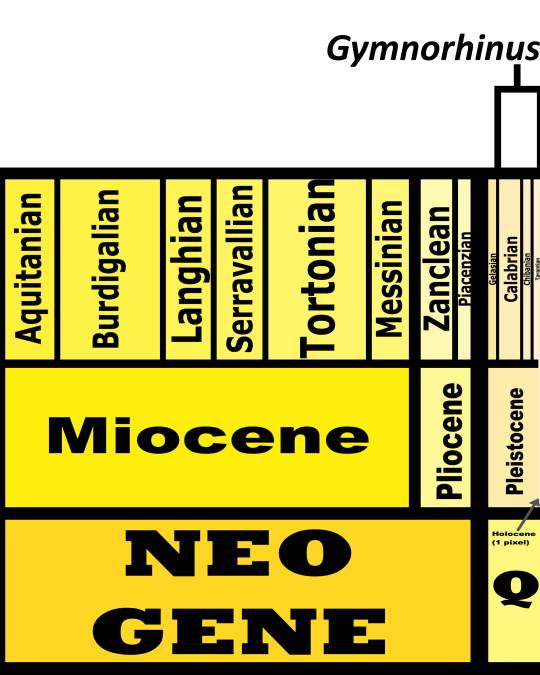

Time and Place: From 1.8 million years ago through today, from the Calabrian of the Pleistocene through the Holocene

Pinyon Jays are known from the Southwestern United States

Physical Description: Pinyon Jays are beautiful, distinctive blue birds. They range from 26 to 29 centimeters in length, making them somewhat small Corvids. The males tend to weigh more than the females. They are a beautiful blue color, fairly uniform all over their bodies, though they do have white and blue striped throat pouches. They have beady black eyes and long, black beaks. These beaks are very pointed and sharp, and the nostrils on them are completely without feathers - hence the meaning of the genus name. The juveniles tend to be more grey and become blue as they get older.

By Seabamirum, CC BY 2.0

Diet: Pinyon Jays have evolved, specifically, to eat the seeds of Pinyon trees for food. These seeds are very heavy and not great for wind distribution, so they rely on animals to eat them and disperse them. As such, the Pinyon Jay fulfills this role. They’ll eat other seeds too, and supplement their diet with insects and other arthropods and grains.

By John Drummond

Behavior: Pinyon Jays live in large, cooperative, synchronized flocks - of up to five hundred individuals - which move around their ecosystem together in search of their specialized food, usually gotten on the ground or in seed feeders. They make a wide variety of calls, probably more than fifteen of them, allowing them to coordinate their activities and recognize different individuals in the flock. The begging calls of juveniles are also unique per individual, allowing it to be clear to the adults who exactly needs food. These unique calls for each individual Pinyon Jay means that the individuals can recognize each other completely across these giant flocks. They make long, alarm calls that are combinations of other calls; and they can make very long rambling songs for twenty or more minutes at a time. These giant flocks will roam over large areas, moving nomadically in search of their favorite flocks.

By Noah Strycker

Pinyon Jays do cache food, allowing for seeds to be grabbed when needed during development, courtship, nest building, egg laying, and incubation. They’ll fly many miles in order to cache seeds, usually in the Fall, and they’ll rely on these cached seeds during the cold months. They will often move the seeds as well, in order to avoid theft from other birds. They’ll cache them in the ground, usually buried in dead needles and twigs - so don’t throw out or pick up such piles!!! Let your fall leaves lie on the ground!!! They will switch to caching in trees when the ground gets too hard to dig into. They remember the location of their caches for at least a week, though it is possible they can remember these locations for longer collectively as a flock.

By Albert Linkowski

These jays begin breeding in the early spring and continue through to autumn if food is particularly plentiful. They form monogamous pairs, possibly for their entire lives (at least as long as ten years), and they make nests together in very synchronized colonies as flocks. Previous children do help build nests, but it’s not as common as in other species. Both parents will build the nests out of a platform of sticks, with a middle layer of coarse grasses woven together, and the nest lined with finely shredded plants, feathers, and hair. They’ll usually place these nests in pine trees. The pair will lay between 2 and 5 eggs which are incubated by the female for two and a half weeks. Both parents will feed and take care of the chicks in the nest for three weeks. The fledglings then gather together in creches which are guarded by a few adults, as foraging resumes back to normal; the parents will return to their fledglings with food every hour. The young depend on their parents for two to three more months. They are then juveniles, learning from the rest of the flock for a few more years. Sometimes these juveniles will move to other flocks, but they usually stay with their parent flocks for their whole lives. Females will begin breeding at 2 years old, and males at 3 years, and they’ll create many broods throughout their lives. They can live for as long as 16 years, in the best of conditions.

By Hal & Kirsten Snyder

Ecosystem: Pinyon Jays stick to woodlands and forests where there are pinyon-juniper trees. They’ll also go to chaparral and scrub oak forests, as well as locations of ponderosa and Jeffrey pines. They can also be found in city and town gardens. Pinyon Jays are highly preyed upon, though their flocking and colonial nesting helps to protect them; they also use pinyon, juniper, and ponderosa pine trees for cover, and rarely stray too far from these sites unless needed to for caching and food storage. These birds also mob potential predators, such as Great Horned Owls, Sharp-Shinned Hawks, Cooper’s Hawks, Red-Tailed Hawks, and Common Grey Foxes. They are also preyed upon by ravens, crows, Steller’s Jays, Abert’s Squirrels, Rock Squirrels, snakes, gray foxes, and domestic cats. Sometimes, these predators pull females from their nests while they’re incubating the young.

By Seabamirum, CC BY 2.0

Other: Pinyon Jays are extremely common birds in their range, but they have undergone extremely rapid population decline due to the loss of its specific woodland habitat. The pinyon-juniper woodland is decreasing due to drought and tree-related diseases. Unfortunately, Pinyon Jays are very nomadic and social, which makes estimating the exact population of these jays fairly difficult. They do use bird feeders in urban and suburban habitats, which means they may be able to get by as their habitat decreases. Interestingly enough, fossils of this bird are known from the last Ice Age, indicating that they did not evolve recently, but have been a fixture of the Southwestern United States for millions of years.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Balda, Russell P.; Bateman, Gary C.; Foster, Gene F. (1972). "Flocking associates of the Pinyon Jay". Wilson Bulletin. 84 (1): 60–76.

Balda, Russell P. 1987. Avian impacts on pinyon-juniper woodlands. In: Everett, Richard L., compiler. Proceedings—pinyon-juniper conference; 1986 January 13–16; Reno, NV. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-215. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station: 525–533.

Barton, Andrew M. (1993). "Factors controlling plant distributions: drought, competition, and fire in montane pines in Arizona". Ecological Monographs. 63 (4): 367–397.

Bateman, Gary C. (1971). "Flocking and annual cycle of the pinyon jay, Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus". The Condor. 73 (3): 287–302.

Bateman, Gary C.; Balda, Russell P. (1973). "Growth, development, and food habits of young pinon jays". Auk. 90 (1): 39–61.

Bednekoff, Peter A.; Balda, Russell P. (1996). "Social caching and observational spatial memory in pinyon jays". Behaviour. 133 (11–12): 807–826.

Clark, L.; Gabaldon, Diana J. (1979). "Nest desertion by the pinon jay". Auk. 96 (4): 796–798.

Cully, Jack F.; Ligon, J. David (2010). "Seasonality of Mobbing Intensity in the Pinyon Jay". Ethology. 71 (4): 333.

Emslie, S. D. 2004. The early and middle Pleistocene avifauna from Porcupine Cave. In A. D. Barnosky (ed.), Biodiversity response to climate change in the middle Pleistocene; the Porcupine Cave fauna from Colorado 127-140.

Gabaldon, D. J.; Balda, R. P. (1980). "Effects of age and experience on breeding success in pinon jays". American Zoologist. 20 (4): 787.

Gottfried, Gerald J. 1987. Regeneration of pinyon. In: Everett, Richard L., compiler. Proceedings—pinyon-juniper conference; 1986 January 13–16; Reno, NV. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-215. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station: 249–254.

Gottfried, Gerald J. 1999. Pinyon-juniper woodlands in the southwestern United States. In: Ffolliott, Peter F.; Ortega-Rubio, Alfredo, eds. Ecology and management of forests, woodlands, and shrublands in the dryland regions of the United States and Mexico: perspectives for the 21st century. Co-edition No. 1. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona; La Paz, Mexico: Centro de Investigaciones Biologicas del Noroeste, SC; Flagstaff, AZ: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: 53–67.

Lanner, Ronald M. (1981). The Pinon Pine: A Natural and Cultural History. University of Nevada Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-87417-066-5.

Leidolf, Andreas; Wolfe, Michael L.; Pendleton, Rosemary L. 2000. Bird communities of gamble oak: a descriptive analysis. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-48. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Ligon, J. David (1974). "Green cones of the piñon pine stimulate late summer breeding in the piñon jay". Nature. 250 (461): 80–2.

Marzluff, John M.; Russell P. Balda. 1988. Resource and climatic variability: influences on sociality of two southwestern corvids. In: Slobodchikoff, C. N., ed. The ecology of social behavior. [Publication location unknown]: Academic Press, Inc.: pp. 255–283.

Marzluff, John M.; Balda, Russell P. (1988). "The advantages of, and constraint forcing, mate fidelity in pinyon jays". Auk. 105 (2): 286–295.

Marzluff, J (1988). "Do pinyon jays alter nest placement based on prior experience?". Animal Behaviour. 36: 1.

Marzluff, J. M.; Balda, R. P. 1990. Pinyon jays: making the best of a bad situation by helping. In: Stacey, Peter B.; Koenig, Walter D., eds. Cooperative breeding in birds. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press: pp. 197–238.

Marzluff, J. M; Russel P. Balda (2010). The Pinyon Jay: Behavioral Ecology of a Colonial and Cooperative Corvid. London: T & AD Poyner. p. 39.

Marzluff, J. (2019). Pinyon Jay (Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Short, Henry L.; McCulloch, Clay Y. 1977. Managing pinyon-juniper ranges for wildlife. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-47. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station.

Springfield, H. W. 1976. Characteristics and management of southwestern pinyon-juniper ranges: the status of our knowledge. Res. Pap. RM-160. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station.

Stotz, Nancy G.; Balda, Russell P. (1995). "Cache and recovery behavior of wild pinyon jays in northern Arizona". The Southwestern Naturalist. 40 (2): 180–184.

Stuart, John D. 1987. Fire history of an old-growth forest of Sequoia sempervirens (Taxodiaceae) forest in Humboldt Redwoods State Park, California. Madrono. 34(2): 128–141.

Stuever, Mary C.; Hayden, John S. 1996. Plant associations (habitat types) of the forests and woodlands of Arizona and New Mexico. Final report: Contract R3-95-27. Placitas, NM: Seldom Seen Expeditions, Inc.

Tomback, Diana F.; Linhart, Yan B. (1990). "The evolution of bird-dispersed pines". Evolutionary Ecology. 4 (3): 185.

#Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus#Gymnorhinus#Pinyon Jay#Jay#Dinosaur#Bird#Birds#Corvid#Passeriform#Songbird#Perching Bird#Dinosaurs#Factfile#Palaeoblr#Birblr#North America#Quaternary#Songbird Saturday & Sunday#Granivore

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Love the “corvid-conifer symbiosis” here.

Caption: “The whitebark pine and the Clark’s Nutcracker are evolutionary soul mates that help hold an ecosystem together. At high elevations in the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem, whitebark pines depend entirely on nutcrackers to disperse their seeds. The pine nuts contain more calories than butter and provide food for more than 100 species, including (counterclockwise from bottom left) red squirrel, chipmunk, Cassin’s Finch, grizzly bear, Mountain Chickadee, and Hairy Woodpecker. Whitebark pines are also pioneers in mountain clearings and act as nurse trees (pictured center left) for spruces and firs to grow up. Illustration by Misaki Ouchida, Bartels Science Illustration Intern.”

From this report on Clark’s nutcrackers and whitebark pine in the Greater Yellowstone ecoregion, republished online at The Cornell Lab’s All About Birds publication:

Caption reads: “The twin scourges of blister rust and mountain pine beetles are devastating whitebark pines. The reddish needles of dying trees now cover vast swaths even in wilderness areas. Aerial photo of Yellowstone National Park by Jane Pargiter, EcoFlight.”

The Clark’s Nutcracker Project, led by Anya Tyson along with the Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation, has also produced some good graphics and studies on the relationship between the bird and the tree:

“Whitebarks often stabilize the soil in extremely cold and dry conditions ...”

“... These [whitebark pine] cones do not open on their own -- they must be pried open by nutcrackers ...”

Squirrels stash nutritious pine cone matter in middens, and these middens are important for grizzly bears:

“High-calorie whitebark pine nuts are esepcially important -- in a recent study near Jackson Hole, nutcrackers didn’t breed following years with low whitebark cone crops. [...] An individual nutcracker can cache [...] up to 98,000 conifer seeds in a season.“

From National Parks Service:

“Whitebark pine seedlings sprout almost exclusively from Clark’s nutcracker seed caches.”

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Word vomit about my squirrel

This is Sparkplug. She is a thirteen-lined ground squirrel, like a tiny solo prairie dog. I’ve had her for 4 years now. She was only about a month old (based on development/breeding season) when my dog caught her and I’ve kept her ever since. In a perfect world I would have returned her as soon as I was sure she was unhurt, but just the day before I did not adopt a fledgling robin I found, so all my baby-animal willpower was used up. While researching later that year about why she wasn’t hibernating, one of the research papers (they’re used to study hibernation, so research papers exist) mentioned as an aside that they can’t be returned to the wild after more than a few weeks in captivity because all their territory will have been swiped by others. So she is not only my squirrel, she is My Responsibility. Because she is My Responsibility (and because she is adorable), I want to do right by her, I want her to be as happy and content as a prey animal can be. In this photo she’s in wood shavings. That’s new as of this weekend. It used to be a foot-ish of dirt with some sparse plants. (It’s a 90-gallon fish tank.) The plants got aphids and I got fed up and decided to replace it with wood shavings For Now and if she hated it I’d refill it with dirt, with BETTER dirt that will grow plants other than “soil amendment seed mix,” perhaps even growing things she will want to eat so that I don’t accidentally bring aphids in with wild plants again, and holding water a reasonable amount so that watering the plants isn’t a precarious effort to grow the plants while also not sending water careening into her hidey holes. Anyway. Now that the wood shavings are there... New thoughts are happening? And usually I’d deal with brain-churn by talking to myself while I drove to work but haha offices are no longer a thing, so.

Ways the new bedding affects her [objective-ish]

She has very minimal digging space

She has very minimal hiding space

She has very minimal caching space

Poo is removed fairly promptly, if she doesn’t bury it (In dirt she tends to either dig a toilet den or pile it up behind leaves)

Pee isn’t, unless I see the wet spot and pinch out the shavings (In dirt it soaks into the dirt, which can make the area gross, though I do have an enzyme spray; if I could grow plants it would feed plants)

Ways the new bedding affects me [objective-ish]

Is surprisingly noisy for her to play in and is slightly driving me bonkers

Cannot get running wheel to sit in a way that it doesn’t bang on the bottom when she runs, is also noisy

I get to see her a lot more?

It looks better in pictures

Behaviors Sparkplug is exhibiting/things I think she is thinking [speculative]

Trying to dig anyway; just instinct or does not having underground shelter freak her out?

Is very active; perhaps because everything is new and shiny OR because her hiding space is too small to chill out in?

Drinking a lot more water; was she getting her needs from plant-water before, or are the wood-shavings dehydrating to live in, or is she just THAT much more active?

Apparently she likes to climb on things? (I don’t think she’s looking for escape; I tipped over her running wheel for some quiet time and she jungle-gym’d all over and under it)

Future concerns [very speculative]

How is she going to feel when I have to take a whole bunch of bedding/ out because it smells? (Picking her up to put in a different box isn’t viable, I did not handle her enough as a wee squirreling, she is less of a pet and more of a personal zoo exhibit, we are acquaintances but not friends)

Not to mention the newspaper under the bedding??

How much am I going to hate changing her bedding?

How much of my worry about wood shavings is just because I’ve collected seeds and rocks and sticks like I’m already planning dirt and I subconsciously don’t want that to go to waste?

I don’t know if this fish tank currently holds water (for after Sparkplug) but her digging in the corners can’t improve those odds.

Thoughts on going back to dirt [speculative]

What if stuff still doesn’t grow in it (I am not toooo concerned with this, I think that getting good soil should do the trick)

Ugh so much work to put the dirt in, but less maintenance after?

Or am I lying to myself about the maintenance, gods forbid I get aphids again

She eats seeds which makes planting the tank sometimes frustrating

#i don't know if I need advice or a kick in the pants#cute#cute animals#brain dump#squirrel#pet advice#animal advice#addie talks

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

my 42 favorite quotes from code bc i’m avoiding homework again

“‘I re-jiggered the settings to ignore trash metal. No more false alarms.’ ‘No more anything. It just beeps.’” (12)

“‘This game is popular?’ Ben was sitting on his tackle box in the shade of a large elm. ‘Sounds pretty nerdtastic to me.’ ‘We can’t all practice birdscalls like you.’” (18)

“‘This watch is low-rent. Plus, I’m getting a new one for my birthday. But you owe me, Stolowitski.’ ‘Owe you what?’ Hi said. ‘Who wears a wristwatch anymore? Cavemen?’” (22)

“‘Coop really doesn’t like that box.’ I knelt and rubbed the edgy wolfdog’s snout. ‘It better not be stuffed with dead squirrels or something.’ … ‘It’s not a rodent coffin!’ Hi huffed. ‘This cache is legit. You’ll see.’” (22-23)

“‘Don’t use up too much drive space,’ I warned, watching the screen from over his shoulder. ‘We bought this stuff to research parvovirus, not so you can watch “Boom Goes the Dynamite” twenty times a day.’” (53)

“Frustrated, Hi rose and wandered to the computer. ‘I’m going to check my email.’ ‘I’m going to kill myself,’ Ben muttered. Shelton ignored them.” (56)

“Soooo many dorks,’ Ben muttered, his coal-black eyebrows forming a steep V. ‘A giant nerd army, digging up plastic boxes they hide for each other.’ ‘Like everything you do is cool,’ Hi snorted. ‘Still have that ninja costume you wore to my twelfth birthday party?’” (62)

“‘Wait.’ Ben glanced from face to face. ‘We’re actually going to pursue this nonsense? We suddenly care what this fruitcake hid in a box somewhere?’” (65)

“‘We’ve got over an hour before dark.’ I yanked my hair into a ponytail. ‘Let’s show Mr. Gamemaster how quickly Virals solve puzzles.’ … ‘We’ve got to work on our decision-making process.’ Shelton was shaking his head. ‘Right now, we just follow Tory over every cliff.’” (74)

“Hi called into the black. ‘Your cache is mine, clown! I’m coming to getcha! Uncle Hiram’s got the scent!’ His words echoed in the darkness as he scrambled through the opening. ‘Zip it!’ Shelton hiss-whispered. ‘This building is struggling to hold your buck-sixty. Don’t yodel the roof down on our heads.’” (82-83)

“‘This is stupid.’ Shelton started toward the doorway. ‘Let’s bounce. We can toss that iPad in the freaking harbor.’” (90)

“‘Watch where you’re going,’ Ben snapped. ‘I am,’ Jason said dryly. ‘I’m going to chat with Tory.’” (100)

“‘Hey, check this weirdo out.’ Hi was inspecting a bust on the mantel. ‘This face is ninety percent eyebrow. What do you wanna bet he owned slaves?’ Scowling to match the carving’s expression, Hi spoke in a gravelly voice. ‘In my day, we ate the poor people. We had a giant outdoor grill, and cooked up peasant steaks every Sunday.’” (106-107)

“‘State your business.’ ‘To see my father.’ A beat. ‘That’s usually going to be my business, FYI.’” (112)

“Hudson’s eyes narrowed. ‘Dodgeball?’ ‘District champs.’ Hi pounded his chest. ‘I’m a gunner. The key is to reach the balls first, and then throw with a little touch of spin, so that—’” (113)

“Jason had attended debutante balls. Knew the drill. My crew would have to conduct research on YouTube. Jason was popular on the cotillion scene. My guys weren’t even on the radar. Asking Jason would get Whitney off my back. Inviting only Morris Island boys might plummet her into a depression.” (132)

“I wore a white tank and jeans, shooting for ‘sexy-casual.’ Hoping it wasn’t ‘left farmhouse, got lost.’” (170)

“‘It has to mean something!’ Hi slapped a knee in frustration. Shelton glanced up from his iPhone, but when Hi didn’t elaborate he resumed surfing. … ‘Care to elaborate?’ I was sitting between Hi and Shelton in the stern. ‘Or was that a yoga move I don’t know?’” (233)

“Hi looked at me strangely. ‘We’re a little busy Friday night.’ ‘Busy? Doing what?’ The boys exchanged a look. Hi snorted. ‘I don’t know about you,’ Shelton said, ‘but I’m escorting my friend Victoria to her debutante ball.’” (235)

“‘Your advice, remember? No fear?’ Instantly regretted. I didn’t want Chance thinking about last summer. ‘Oh, I recall.’ Chance smiled thinly. ‘I haven’t crashed on your floor so many times that I’d forget.’” (240)

“‘I found something interesting,’ Marchant continued. ‘Are you free to meet? I’m headed out for a caffeine fix in thirty minutes.’ Um, what? Did this guy not understand I was fourteen? Bolton wasn’t big on students popping out for midday lattes.” (245)

“‘Ben, stop the boat.’ He looked at me funny. ‘We’re in the middle of the ocean, Victoria.’ ‘Stop the damn boat!’ Ben rolled eyes, but eased off the throttle. Sewee decelerated until we just bobbed along with the current. ‘Did you want to jump in?’ Ben asked dryly. ‘Water’s pretty cold in October.’” (251-252)

“‘Okay, people.’ Ben crossed his arms. ‘Care to share?’ ‘No big deal.’ Shelton’s tone was nonchalant. ‘Just a quick stop at Mepkin Abbey to get a new headshot of Mr. Dead Guy.’” (260)

“‘Options?’ Ben asked as he pulled out onto the highway. ‘I think some charitable work might be in order,’ Hi said. ‘I’m not a Jesus man, but I’m pretty sure getting ripped a new one by a monk is bad karma in any religion.’” (264)

“‘Oh man, she really did it this time!’ ‘Should we call the nurse?’ Panicky. ‘An ambulance?’ ‘And say what, exactly?’ hissed a third. ‘That our friend passed out after some bad telepathy?’” (271)

“‘She’s coming around!’ The roundest shape coalesced into Hi. ‘Tor? You okay? If you’ve gone vegetable, blink at me.’” (271)

“My splitting headache had proved the experiment had been dangerous. Had I learned my lesson? Probably not.” (273)

“Hi, naturally, had opted for flair. His tux was crushed purple velvet with tails, accented by all white silk—tie, vest, gloves, and suspenders. He completed the outfit with a freaking top hat and cane. Whitney had nearly fainted on seeing him.” (279)

“‘Those who enlist complete a rigorous program combining academics, physical fitness, and military discipline.’ … ‘So—book learning, push-ups, and war games.’ Hi ticked off fingers as he spoke. ‘Check, check, and check. Plus gray is my sexy color.’” (279)

“‘Paging Miss Brennan.’ Chance waved a hand before my eyes. ‘You okay?’ No. ‘Yes. I’m just…surprised I’ll be first.’ ‘I’m sure you’ll dazzle. Until then.’” (286)

“‘Gamemaster?’ Jason looked confused. ‘Search the basement? What are you talking about?’ ‘Oh, we’re, um, playing a pretty fierce game of Dungeons and Dragons,’ Hi stammered. ‘I’m, like, the head…unicorn master, and Tory has to find my magic…beans. Seeds.’” (299)

“‘Always trapped!’ Shelton actually stamped a foot. ‘Always underground! If we get out of here, I’m moving to a high-rise on a mountain-top. Penthouse! And y’all ain’t invited!’” (304)

“‘I assume there’s no antique cash register in need of special oil?’ Jason said. No one bothered to answer.” (331)

“He launched into an improvised tale of woe and misfortune. We’d found ourselves in the dark. Flustered and disoriented, we’d blundered through an emergency exit. Then we’d tumbled down a staircase in a complicated domino sequence that incorporated each one of us. The story was bizarre, confusing, and wildly improbable. They’d bought it without hesitation.” (333)

“‘Yet you four ripped the grate from its tracks. Then you ripped the tracks from the wall, bending the metal bars like they were drinking straws. How? How is that possible?’ ‘I read once where this guy in Ulan Bator powerlifted a Chinese tank after—’ ‘Can it, Stolowitski. Let Tory explain.’” (335)

“‘You look ready to chew nails.’ Shelton grinned at me from his own stoop. ‘There’s a certain murderer I’d like to chat with.’” (340)

“‘You okay, Tor?’ Shelton had a sandbag on one shoulder, hauled up from the beach. ‘We don’t have time for an ER run.’ ‘We could amputate,’ Hi suggested. ‘Shelton, get the whiskey.’” (342)

“‘I called Marchant’s office and left a message. Less than a minute later, my cell rang and March—’ I gritted my teeth, ‘—the Gamemaster asked me to meet him at City Lights Coffee. So I did.’ ‘So dumb,’ Hi muttered. ‘And it really was a murderer.’” (350)

“‘And you know this how?’ … ‘I dreamed it.’ ‘Aha! You dreamed it.’ Hi yawned and rubbed his eyes. ‘I think it’s time we get you medicated.’” (352)

“I turned on Ben and Hi. ‘What about you two? Ready to bail? There’s a deranged psycho out there who knows what your mothers eat for breakfast. That cool with you?’” (353)

“‘Any plan for that bit?’ Shelton asked dully. ‘You keep glossing over how we’re actually gonna make the citizen’s arrest.’ ‘Of course.’ I chucked his shoulder. ‘We’ll improvise.’ ‘Great. Well thought out.’” (362)

“‘You’re a hot, steaming ball of crazy,’ Hi said. ‘You know that, right? Freaking Looney Tunes.’” (373)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

There are advantages to staying home. The obvious, of course, is it lowers your risk of acquiring the coronavirus.

There is another positive upshot of being homebound. It can stimulate our mental psyche. We just need to be observant.

Being retired for a few years now, I quickly grew used to being at home. I thought I knew how to relax and make the best use of my time. The COVID-19 crisis taught me differently.

Having to stay at home, I learned to really pay attention, to simply be thankful, even when the weather was damp and cold. We had a lot of that in April and May all across the eastern U.S. The typically sunny Shenandoah Valley didn’t escape the dullness either.

I savored the stillness and the lack of interruptions to my new sequestered routines. The steady hum of my wife’s sewing machine transfixed me at times. Altogether, she has made over 700 face masks. Others have made many more and donated them to businesses, medical facilities, agencies who assist the homeless, local institutions, and Mennonite Disaster Service.

Rather than grumble about being at home so much, I tried to appreciate each moment at hand. I would often sit at my desk where I write. I raised the Venetian blinds and observed whatever came into view.

Despite the weather, I saw kids on bicycles, people walking dogs, dogs walking people, delivery trucks, northern cardinals searching for food, American robins bobbing along, and gathering nesting material.

I couldn’t count the number of squirrels that came to dig up their buried food caches. Most of the squirrels are gray busybodies. One particular squirrel, however, stood out.

This squirrel was blond, especially its bushy tail. Its pigmentation had to be an anomaly. The squirrely rodent even acted differently, sometimes like it didn’t have a care in the world.

The sun seemed to bleach the squirrel’s tail as it bounded through neighboring backyards on its way to ours. I had seen the squirrel in late winter searching for morsels beneath our birdfeeders. “Blondie” continued to frequent our yard even after I took down the feeders.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

The blond squirrel scurried across the open backyard in the middle of the day, its tail flapping in the wind like a golden, glowing flag. The squirrel played at the birdbath, apparently happy for the opportunity to wash its paws and face. Did it somehow know about the coronavirus?

The unusual-looking squirrel felt at home in our maple trees. On the hottest day of the year so far, it stretched out on our green grass, apparently to cool off in the shade of the maple.

Showing off.

Once rested, it returned to its squirrely antics, devouring juicy maple seeds that had just twirled to the ground. Some of its repertoire of poses were almost comical. Its playful personality matched its coloration.

It’s not like the squirrel had it made, however. Other squirrels chased it, not because of its fur color, but because that’s what squirrels do.

The blond always got away unscathed. When the coast was clear, it reappeared looking for food, or another drink, or just to lounge on a crook in the maple tree, taking in the limited sunshine.

I enjoyed the squirrel’s behaviors and resilience. Unlike the gray squirrels, the blond one somehow seemed contented, satisfied, unfettered, detached from the life of the survival of the fittest of all things wild.

There are valuable lessons to be learned from watching this fantastic squirrel. No matter what life throws at you, relax, enjoy each moment, and above all, don’t worry.

“Blondie.”

© Bruce Stambaugh 2020 Advantages of staying home There are advantages to staying home. The obvious, of course, is it lowers your risk of acquiring the coronavirus.

0 notes

Text

The Piñon Pine - The Indians Own Tree

When I section-hiked the PCT from Tehachapi to Walker Pass several Mays ago, as we neared the northern end of that trip we took a lunch break one day under a grove of piñon pines. As we reached into our pack for our usual lunch of cheese, rye crackers, and salami, we began to notice that the forest floor was littered with pine nuts. While some had become food for rodents, squirrels, and other foraging animals since dropping to the ground the prior autumn, most were so very edible. Soon we were each on our hands and knees collecting cones and harvesting their delectable contents ($29 a pound at our local co-op). I ate my fill and packed an empty bag with more nuts which I brought home with me when I left the trail. This is David Foscue’s story of the pine nut.

David Foscue

An Evolutionary Feat

As far as trees along the PCT go, it is not impressive. It may be three or four times your height – pretty shrubby. A tree with a trunk six inches in diameter may be over a century old. Its cones take three seasons to mature. But it is a proud little tree, the piñon. John Muir wrote: “A more contentedly fruitful and unaspiring conifer could not be conceived.”

Piñons are coveted for their nutitious seeds. One pound of seeds may contain 3,000 calories. The pine nuts were collected by Indians as stores for the winter. Listen again to Muir: “This is undoubtably the more important food-tree on the Sierra, and furnishes the Mono, Carson, and Walker River Indians with more and better nuts than all the other species together. It is the Indian’s own tree, and many a white many they have killed for cutting it down.”

A diligent collector in the prime collecting time can gather up to seventy pounds of the seeds. Humans, of course, are not the only beneficiaries of the piñon’s largess. Pine nuts are a favorite of many animals from the piñon jay to the pack rat — it is reported that over forty pounds of nuts may be found in a pack rat’s cache. The wide popularity of piñon nuts is a matter of survival, for the seeds of the piñon lack wings and depend on animals for distribution.

The piñon of the Sierras is single-needled pine. It is a mutation of the piñon found further east on which the needles appear in bunches of two. The two-needled piñon is subject to infestation by the piñon spindle gall midge which appears to have evolved with the tree. The insect lays its eggs on the flat leaves, when they hatch the larvae crawl into the crotch between paired needles. The irritation caused by the tiny larvae simulates the plant to grow tissue forming a gall over the larval wound. The gall covers the wound but it also protects the enclosed larvae.

The gall midge evolved to inhabit the single-needled piñon which lack the needle crotches to shelter the larvae. According to Ronald Lanner, the single-needle piñon developed from the twin-needled variety but “one of the potential needle sites is suppressed by the … mutation. Our gall midge neutralizes the mutation. The feeding of the larvae suppresses the needle-suppression mechanism, allowing both of the potential needles to develop, though they reach only a fraction of their full length. The needles are galled and the larvae grow up in the same type of needle-crotch home as those in … two needled pines.” Needles at unaffected locations on the tree remain single.

Kit Carson, John C. Frémont and the Piñon Nut

The piñon played a supporting role in two dramas that have become part of the lore of the PCT. One involved “The Pathfinder,” John C. Frémont, extraordinary adventurer and the first Republican presidential candidate. The other tale involves the ill-fated Donner party.

Frémont, and his scout, Kit Carson, led the first recorded winter crossing of the Sierras. What Frémont expected to take a week became an ordeal of five weeks. As they faced the Sierras their supplies were running low. Fortunately Indians supplied them with pine nuts! On January 24, 1844, Frémont wrote:

A man was discovered running towards the camp as we were about to start this morning, who proved to be an Indian of rather advanced age–a sort of forlorn hope, who seemed to have been worked up into the resolution of visiting the strangers who were passing through the country. He seized the hand of the first man he met as he came up, out of breath, and held on, as if to assure himself of protection. He brought with him, in a little skin bag, a few pounds of the seeds of a pine-tree … . We purchased them all from him.

The Indians tried to discourage Frémont from crossing the Sierras believing it impossible in winter, but Frémont was nothing if not rash. Frémont mentions trading for pine nuts several more times before reaching the snows: “The Indians brought in during the evening an abundant supply of pine-nuts, for which we traded with them.” Fueled, in part, by pine nuts, the expedition fought through the winter snows, eventually cresting the Sierras on February 20, 1844, at the pass that now bears Kit Carson’s name.

The Donner Party - Rescued by Pine Nuts?

George Donner’s group was not as successful in its attempt to cross the Sierras two winters later. In a snow storm, the party reached what is now known as Donner Lake in early November 1846. Attempts to reach the pass failed and the party returned to the lake and settled in. Although many of their animals froze providing unexpected food, their provisions were soon exhausted and the new settlers faced slow starvation.

On December 16 a group of fifteen left the lake in an attempt to cross the mountains for help. Using the same term Frémont applied to the old Indian who first provided him piñon nuts, they called themselves the “Forlorn Hope Party.” Death reduced the group to seven. As we now know, the dead sustained the living.

The forlorn and depleted party finally came to an Indian village on January 10. The Indians provided acorn bread to the party but the group was so weakened their strength could not be restored. The leader, William Eddy, became sick on the bread. Donner’s Daughter, Eliza, writes how Eddy regained his strength:

… the chief with much difficulty procured for Mr. Eddy, a gill of pine nuts which the latter found so nutritious that the following morning, on resuming travel, he was able to walk without support.

Eddy walked fifteen miles that day to a small settlement where he was able to organize a party to rescue the other six surviving members of Forlorn Hope. Eventually three rescue parties, including one led by Eddy, were organized to return to Donner Lake. Forty-six members of the Donner party were rescued. Forty-two did not make it. The toll surely would have been greater but for the pine nuts given by the Indians to Eddy.

Think about the Donner party the next time you sprinkle piñon pine nuts on your salad.

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Dancing on Bear Ground it’s a cool, moist, green, morning in mid-March on the Mayacamas walking along the mowed roadside we’re greeted by the bright pink flowers … of weedy little storks-bills all facing the sun, their color reminds us of shooting star flowers heading down thru abandoned pasture toward an old oak grove, we look for some native wildflowers … between the annual grass seedlings and straw we find bright pink blooms of cut-leaved geranium from the old world the flower color and round leaves evoke a teasing faint memory of checker-blooms between big old bunch-grass bunches looking, looking and looking for wildflowers … in acres of annual grass seedlings and straw with weeds we find only 5 individual native plants entering the woods we walk past many small young oaks then reach a small grove of stunningly large oaks, one after another, each bigger yet, we sit and lunch in the shade of the largest (she is older than the oldest road in the region!) “grandmother, we thank you for good company and for the shade” after lunch we head down through a big patch of annual grassland churned over by pigs all the soil bared here, we imagine grizzly bears churning up the ground between ancient bunch-grasses bears digging for bulbs and mice bears …. ‘bear’ing the soil between the bunches ‘bear’ ground a seed-bed for new bulbs and biodiversity anchored by the bunch-grasses here we imagine bears … wading in waves of wild hyacinth a… blue … wildflower … sea waves cresting with bunch-grass tassels foam of tidy tips and popcorn flowers splashings of bird’s-eye gilia of lupine, the air aswarm with a hundred kinds of native bees and butterflies bears …. bearing the soil between the bunches bear ground a seed-bed for new bulbs and a riot of wildflowers between the bunches are runways for mice and lizards, churnings of gophers, each leaving their own wake, a patchwork … of tiny … tended, tilled and trampled places, their activity shaping small spaces for flowers and bees … bee-grounds … for … nesting, today a single wild hyacinth waves at a few passing woodland satyrs today we hike thru depleted former pasture and wonder ‘where have all the wildflowers gone?’ crossing the ravine, we pass through young oak woodland with annual grasses and a scattering of small new bunch grass babies that haven’t grown bunchy accompanied by a sparse sprinkling of wildflowers rejoining the road, we’re held-up at the first road bank by a gang of shooting stars a few buttercups spread into the nearby grasslands and sleepy milkmaids follow the road, their heads drooping scarlet larkspur will soon bloom on a steep roadcut seedlings of Chinese Houses and Clarkia’s promise later blooms on these roadcuts too a few more curves and we blink at a crowd of baby blue-eyes blinking back from another bank and we wonder, can we bring these wildflowers away from the roadsides and back into the grasslands … again? let’s try to bring them back let’s gather seeds let’s bring these ancient partners … back … into the dance let’s bring the patterns rhythms synergies … together? let’s give a handful of wildflowers seeds to deer-mouse to jumping mouse so they can cache and plant them together with mouse pellets filled with spores of their favorite fungi people, the bears, the mice each carrying seeds and fungi let’s come together, squirrels too, and birds, each … carrying seeds and spores let’s come together native bees, butterflies let’s come together bunch-grasses and bears, hyphae and wildflowers… let’s come back together and dance let’s sing let’s relearn the rhythms and dance with bears, bulbs, bees, butterflies, buttercups let’s sing and dance with the beauty of it let’s’ sing and dance … together … again!

ds_2015-16

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

How Do Squirrels Remember Where They Buried Their Nuts?

By Emma Bryce

November 17, 2018

Few things symbolize the onset of fall quite so well as the sight of a squirrel scampering around a park, industriously burying nuts. As the weather cools and the leaves turn, squirrels engage in this frantic behavior to prepare for the upcoming shortages of wintertime.

But have you ever wondered how effective the squirrel's outdoor pantry project could really be? After going to all that effort to conceal its winter stash, how does the squirrel actually find the buried treasure again, when it's needed most?

First, let's backtrack slightly, because the way that squirrels bury their food yields some interesting clues. Animals that store food to survive the winter don't just do so randomly: They typically use one of two strategies. Either they larder-hoard — meaning they store all their food in one place — or they scatter-hoard — meaning they split up their bounty and stash it in many different locations.

Most squirrel species are scatter-hoarders — hence the characteristic dashing they do between different piles of buried food. "This style of food storing probably evolved because it reduces the risk of suffering a major loss," said Mikel Maria Delgado, a postdoctoral fellow at the School of Veterinary Medicine at the University of California, Davis, who has studied squirrel behavior for severalyears. In other words, the more widely dispersed the food, the lower the risk that a hungry competitor will discover the squirrel's entire supply and destroy it in one go.

In recent research published in the journal Royal Society Open Science, Delgado showed that squirrels will arrange and bury their stash according to certain traits, such as the type of nut. This is known as "chunking," and research shows that in other species, such behavior allows animals to mentally organize their hoard, which may help them remember where it is later on.

That banishes any idea that squirrels are haphazardly chucking bits of food down holes in the ground, and simply hoping to stumble across it later. "I think the body of research about how squirrels handle and bury food clearly demonstrates that their behavior is not random," Delgado told Live Science. On the contrary, there appears to be a meticulous strategy behind the way they store food.

How does that translate into how they find their artfully concealed stash? Depending on the squirrel species and the type of nut, squirrels are generally able to retrieve up to 95percentof their buried food, research shows. So there's clearly more than chance behind this process.

It was long believed that squirrels simply relied on their sense of smell to find their food. But while smell definitely comes into it, a growing body of research suggests that memory plays a much more crucial role.

A seminal 1991 research paper published in the journal Animal Behavior showed that even when multiple grey squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis) bury their stash in close proximity to one another, individuals of this species will remember and return to the precise locations of their personal cache. This is echoed by multiple other studies, showing that the squirrels' spatial memory helps them map out the territory around them to find their food. Under certain conditions — like when their nuts are buried under snow — a sense of smell won’t alwaysbe effective in helping them find food. So, it makes sense that squirrels couldbe relying on other cues.

"While scatter-hoarding squirrels probably also use their sense of smell to locate caches, they do remember their caches. We don't know the exact mechanisms, but it probably includes spatial cues in the environment," Delgado told Live Science.

Pizza Ka Yee Chow, a postdoctoral research fellow at Hokkaido University in Japan, who studies squirrel cognition, agrees. "From my own observation, I think they are using landmarks. They recognize the trees, and they are gauging the distance between themselves, the tree and their own nests," she said.

The organizational chunking behavior, which Delgado identified for the first time in squirrels, may also function to provide memorable cues about the food they're burying. This tactic could "decrease memory load," helping squirrels recall where they put it, Delgado wrote in the Royal Society Open Science study. "No one has directly tested what the potential benefits of chunking would be for squirrels, but we anticipate it might aid in future retrieval of caches," she said.

Researchers have observed that when squirrels scatter-hoard in confined areas, they also seem to be able to remember the location of their caches in relation to one another, suggesting that they build a detailed mental map of where their food lies.

Other studies on squirrel behavior have added weight to the idea that memory underlies squirrels' nut-retrieving skills. In Chow's study on squirrels, published in 2017 in the journal Animal Cognition, she showed that impressive memory spans enable squirrels to successfully recall the solution to a difficult task (manipulating levers to open a hatch that releases a prized hazelnut) more than two years after they first learned it. "They always a find a way to do what they want to do," Chow told Live Science. "They are so dedicated!" This also points to long-term memory as part of the reason squirrels can so specifically recall the location of their nutty bounty.

Over the decades, a plethora of studies have revealed that there's more to squirrels than meets the eye. For instance, researchers think squirrels may even be doing quality control on their bounty. The animals have been observed pawing over nuts and seeds for long periods of time before they bury their stash — something that might help them select nuts with the highest nutritional content, and those least likely to perish underground.

Squirrels will often also meticulously rearrange leaves over disturbed soil to hide their burial sites. Commonly, they also pretend to bury nuts when other squirrels are watching — and then scurry off to a secret location where they actually hide their edible treasures.

In essence, squirrels may covertly hide their nuts, but there's nothing nutty about this behavior. Said Chow, "We think these little creatures may be way smarter than we thought."

0 notes

Text