#duwayne dunham

Text

#movies#polls#homeward bound: the incredible journey#homeward bound the incredible journey#homeward bound#90s movies#duwayne dunham#michael j fox#sally field#don ameche#requested#have you seen this movie poll

415 notes

·

View notes

Photo

TWIN PEAKS S01E02 “TRACES TO NOWHERE” (1990) dir. DUWAYNE DUNHAM

387 notes

·

View notes

Text

Halloweentown (1998) | dir. Duwayne Dunham

299 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cody’s not just growing up… he’s growing fins!

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Homeward Bound The Incredible Journey#Homeward Bound#Duwayne Dunham#Sheila Burnford#Caroline Thompson#Linda Woolverton#90s

48 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Twin Peaks. S1/E1: “Episode #1.1″ (David Lynch, Duwayne Dunham, 1989)

Reinig Bridge / Snoqualmie Valley Trail - Reinig Bridge

Snoqualmie, Washington (USA)

Bridge over the Snoqualmie river

Type: truss bridge.

#twin peaks#twin peaks season 1#twin peaks s1 e1#twin peaks episode 1#twin peaks pilot#david lynch#duwayne dunham#1989#reinig bridge#snoqualmie valley trail#snoqualmie#washington#USA#snoqualmie river#Truss Bridge#bridge#TV series#tv#ronette's bridge

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Halloweentown (1998, Duwayne Dunham)

12/01/2024

Halloweentown is a television film, the first in the Halloweentown saga, whose world premiere was dated 17 October 1998.

Doris Roberts was initially offered the role of Aggie Cromwell, but had to give it up because she was busy filming Everybody Loves Raymond at the time.

Halloweentown kicked off the Halloweentown saga which is made up of 3 other episodes: Halloweentown II: Kalabar's Revenge, Halloweentown High and Return of Halloweentown. In the last film the protagonist role was played by Sara Paxton.

#halloweentown#Fiction televisiva#1998#doris roberts#everybody loves raymond#halloweentown ii: kalabar's revenge#halloweentown high#return to halloweentown#sara paxton#List of Disney Channel original films#Duwayne Dunham#debbie reynolds#kimberly j brown#joey zimmerman#judith hoag#halloween#witchcraft#mayor#skeleton#mansion#merlin#Goblin#werewolf#ghost#vampire#jack o lantern#List of Halloweentown characters#Phillip Van Dyke#Robin Thomas#kenneth choi

1 note

·

View note

Text

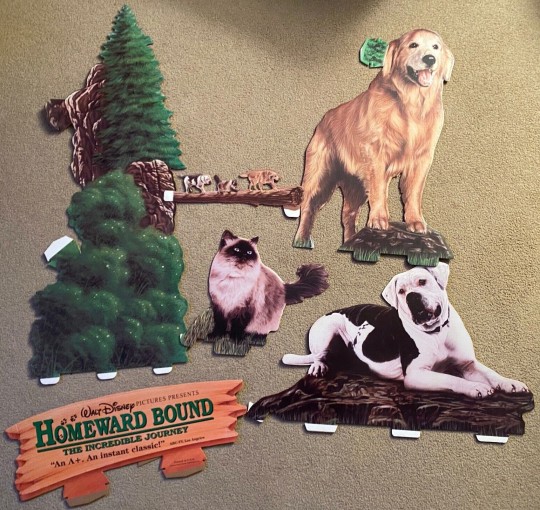

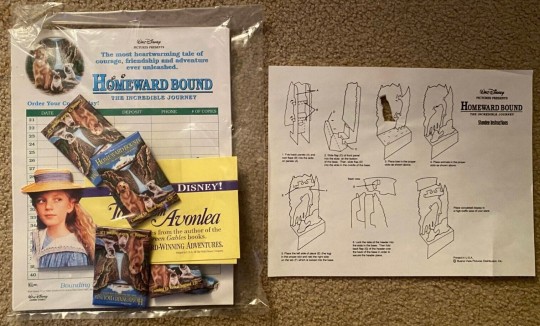

Homeward Bound: The Incredible Journey (1993)

1 note

·

View note

Text

🎃 31 DAYS OF HALLOWEEN 🎃 day sixteen / thirty-one

HALLOWEENTOWN

Directed by Duwayne Dunham (1998)

#halloweentown#halloween2023#disneyedit#userreed#ruinedchildhood#chewieblog#userstream#userbbelcher#throwbackblr#filmedit#moviegifs#filmgifs#movieedit#fyeahmovies#dailyflicks#tvfilmsource#tvfilmgifs#tvfilmedit#tvfilmspot#tvfilmdaily#cinematv#cinemapix#filmtv#*

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

It's so strange. I know I should be sad, and I am, part of me is. But it's like... it's like I'm having the most beautiful dream... and the most terrible nightmare, all at once.

Twin Peaks (1990-1991)

1.02 - Traces to Nowhere dir. Duwayne Dunham

#twin peaks#twinpeaksedit#tvedit#usersugar#userelissa#twinpeaksdaily#userrobin#myellenficent#horrorgifs#usertelevision#chewieblog#userveronika#uservee#mikaeled#userstream#underbetelgeuse#usercande#tuserjord#gifs*#twinpeaksrw

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Twin Peaks, 1990, dir. Duwayne Dunham

SE01E02 Traces to Nowhere

318 notes

·

View notes

Text

Halloweentown, 1998

Dir. Duwayne Dunham

#halloweentown#happy halloween#october 31st#halloween#spooktober#reblog#horror blog#disney#90s nostalgia#1990s#90s movies#disney channel#pumpkin#witch#skeleton#witches#pumpkin carving#like for like#horror tumblr#user edit#halloween edit#like for real#follow me#follow#share for more#halloween night#halloween season#halloween costume#october 31

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Halloweentown (1998) dir. Duwayne Dunham

#newsflash buddy! i still don't know how to color!#film: halloweentown#movies#halloweentown#mythtakensgif#disney channel#dcom#halloween dcom#filmgifs#kimberly j brown#debbie reynolds#judith hoag#joey zimmerman#emily roeske#robin thomas#nurmi husa#johnny useldinger#vincent gambino#kenneth choi

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

🎃 TJ MIKELOGAN'S HALLOWEEN 2023 EVENT 🎃

DAY 11: A non-scary Halloween movie or series

HALLOWEEN VIA DISNEY+

Halloweentown (1998) dir. Duwayne Dunham

Haunted Mansion (2023) dir. Justin Simien

Loki (2021 - ) dir. Kate Herron

Lonesome Ghosts (1937) dir. Burt Gillett

Moon Knight (2022) dir. Mohamed Diab, Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead

The Old Mill (1937) dir. Wilfred Jackson and Graham Heid

The Scream Team (2002) dir. Stuart Gillard

Trick or Treat (1952) dir. Jack Hannah

Wandavision (2021) dir. Matt Shakman

Werewolf by Night (2022) dir. Michael Giacchino

#USERTJ#horror#horroredit#fantasy#fantasyedit#halloweenedit#disney#disneyedit#marvel#marveledit#halloweentown#haunted mansion#loki series#lokiedit#lonesome ghosts#moon knight#moonknightedit#the old mill#the scream team#trick or treat#wandavision#wandavisionedit#werewolf by night#werewolf by night special#werewolfbynightedit#2023 halloween season

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

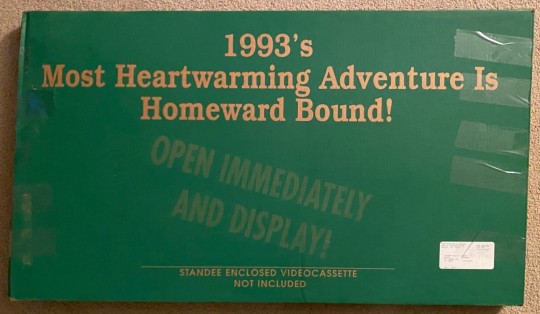

Laura Dern, Isabella Rossellini, and Kyle MacLachlan in Blue Velvet (David Lynch, 1986)

Cast: Isabella Rossellini, Kyle MacLachlan, Dennis Hopper, Laura Dern, Hope Lange, Dean Stockwell. Screenplay: David Lynch. Cinematography: Frederick Elmes. Production design: Patricia Norris. Film editing: Duwayne Dunham. Music: Angelo Badalamenti.

Would there have been a Quentin Tarantino if there hadn't been a David Lynch? Blue Velvet represents an opening up of mainstream moviemaking to the perverse underside of American experience. It had been approached before, in 1940s film noir, for example, but only by suggestion. In the era of the nascent Cold War, unusual sexual behavior was typically presented as the product of decadent cities like New York and Los Angeles. But in Lynch's film, made at the height of the Reagan era, it underlies the wholesome atmosphere of a small town where the fireman smiles and waves as he passes by. The film noir detective was usually repulsed by what he saw, not fascinated and drawn in the way Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan) is. Jeffrey, barely out of adolescence, teams up to explore the mystery of Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini) with a teenage girl, Sandy (Laura Dern), who is both disgusted and fascinated by what she learns. The use of songs like Bobby Vinton's "Blue Velvet" and Roy Orbison's "In Dreams" suggests the way American pop culture, aimed at the young, floats atop a sea of darkness that it only thinly hides. In the end, of course, everything is cleaned up: the vicious Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper) gets what's coming to him and Dorothy is reunited with her child. Even Jeffrey's father (Jack Harvey), incapacitated by a stroke while watering his lawn at the beginning of the film, is restored to health. Sandy has earlier told us about her nightmare in which the horrors will only disappear when the robins fly down and bring a "blinding light of love." So in the end a robin appears on the windowsill, with one of the disgusting insects we saw at the film's beginning under the grass of the Beaumonts' lawn in its mouth. But Lynch mocks the happy ending by clearly showing us that it's a fake, an animated stuffed robin.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

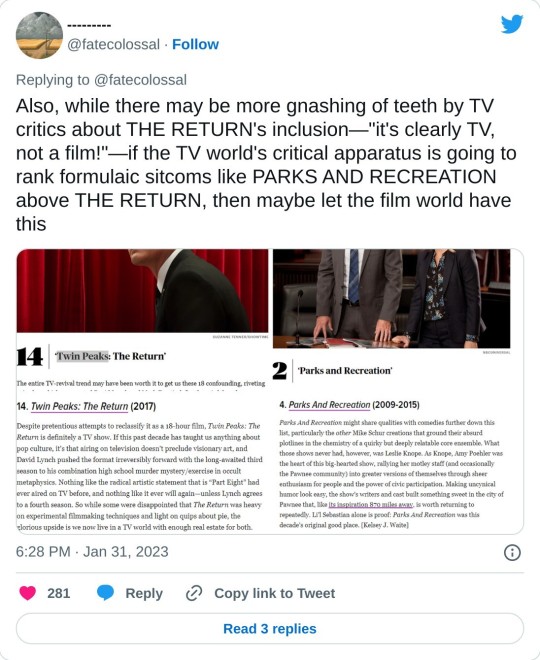

The Case for Considering TWIN PEAKS: THE RETURN a Long-Form Film

That discourse you dislike is back in style.

“It truly is a film and anybody who would even venture to say otherwise, they’re mistaken.” – Duwayne Dunham, editor for TWIN PEAKS: THE RETURN

“Categorizing TWIN PEAKS S3 as ‘a film’ sits in the same embarrassing school as labeling Ari Aster movies ‘Elevated Horror.’ People so embarrassed to adore something in a medium/genre ‘beneath’ their tastes they have to rewrite definitions to accommodate their own insecurity.” – viral tweet by A.B. Allen

With TWIN PEAKS: THE RETURN being ranked #152 in the extended version of Sight and Sound's prestigious poll of "The Greatest Films of All Time" released a couple weeks ago, the old debate over whether it is ever appropriate to consider TP:TR a film, first begun after the work’s original release in 2017, surfaced for one more iteration. Although it is a small-stakes debate, seemingly only of importance for list-making, media beat assignments, and comparative academic analyses, it has proven to stir up some spirited opinions (and jokes). As in previous iterations of the discourse, many have expressed their difficulty at conceiving of TP:TR as anything other than a TV show. And it is easy to understand why the thought of TP:TR as a film strikes so many as preposterous:

It aired in weekly installments, usually about an hour or so long, and many of which ended in similar fashion, with a musical performance at the Roadhouse.

The communal experience, in the summer of 2017, of participating in weekly discussions about each new installment was quintessentially one associates with TV.

TP:TR’s length, at nearly 16.5 hours, far exceeds that of traditional feature films.

And more generally, there is a tendency at times for some to conflate the medium of TV with the formal artistic genre of TV shows, meaning that most things released on TV will have an uphill battle being considered anything other than (or in addition to) a TV show.

Yet there are also strong reasons for considering TP:TR to be a film, reasons that its lead-creatives pointed to after the work’s initial release as examples of how very different it was from TWIN PEAKS’ two TV seasons in 1990-91, and much more similar to their previous experiences working in film. For instance:

Notwithstanding the fact that TP:TR was broken into smaller segments for weekly airings, episodic form is of almost no importance to its structure, which was built as one long, continuous narrative.

Likewise, its production processes were focused on one single entity, the work as a whole, rather than being segmented into individual productions for each episode.

And it was entirely directed by the same person, and jointly written by the same two people, points that (along with the single production process) make it natural to attribute to it a unitary authorship more typically associated with films than episodic TV.

While it is true that TP:TR is not unique among works airing on TV (or streaming) in possessing these qualities, all this seemingly demonstrates is that other works face the same issues of category confusion; to the extent that it is determined reasonable for TP:TR to be considered a film and eligible for inclusion in film rankings like the Sight and Sound list, then these other works should likewise be eligible. While in practice it may often regrettably be the case that the only long TV works that end up being classified as a film are those “directed by people who are already beloved in the film world” (a concern expressed by critic Emily St. James), the remedy should seemingly just be an advocacy for more long TV works to be classified as film, using a more coherent, uniformly applied concept of formal artistic genres.

Given that the respected lead-creatives of TP:TR, veterans of both TV and motion pictures, have expressed at some length the above straightforward reasons for considering the work to be a film, one might have expected their reasoning to be at least acknowledged in the long-running online conversation on the issue. And yet, to read the back and forth over this on Twitter, one could hardly be blamed for concluding that the only real proponents of considering TP:TR a film are either snobs, trolls, or just wildly illogical—an outlook epitomized by the A.B. Allen thread quoted above, and by these other representative tweets:

(1). Snobs

(2). Trolls

(3). Wildly illogical

While I imagine that there are many reasons for this disconnect, I expect that it’s at least partly because, of the TP:TR creatives who have expressed a viewpoint on this, only David Lynch’s views seem to have been widely circulated, and people seem to be very willing either to dismiss his views as the illogical pique of a kooky individualist, or to suggest that he is driven by a snobbish view of TV (as critic Matt Zoller Seitz put it: “I think some part of him still feels that TV is a step down, no matter how much success he's had in it, and despite all he's done to expand its language”). It’s a shame that only Lynch’s brief remarks seem to have at all been paid heed, since other TP:TR creatives besides Lynch have been much more expansive in their remarks on the issue.

Episodic Segmentation vs Continuous Narrative

Take Duwayne Dunham, for instance. The editor of TP:TR, and a longtime veteran of both TV and film, Dunham stresses that its airing on TV has nothing to do with whether it should be considered a film (“television per se, it’s just the medium, Showtime”), and is adamant on one point: unlike the two seasons of TWIN PEAKS that aired in 1990-91, TP:TR was made with almost no attention to forming coherent and satisfying episodic units—a central aspect of how TV shows, as a unique art form, are often defined. “It wasn’t constructed or wasn’t written in that way (as television), it wasn’t shot that way, and it wasn’t cut that way. It was cut to be continuous.... [I]f you cut the titles off in-between episodes and just started with Parts 1 and 2, which came out as the pilot and you put them all together, you would not miss a thing. That’s how it was constructed.” This is, at least in part, why the show’s creators often refer to its individual segments as “Parts,” rather than the traditional “episode” nomenclature used for self-contained installments of (even serial) TV shows. While some critics have rolled their eyes at this terminological flourish, it is nonetheless based in something concrete. Mark Frost, co-writer of TP:TR (and co-creator of TWIN PEAKS), has confirmed that no thought was given to episodic composition during the writing process: “we just wrote as much as we felt needed to be written. We didn’t even think about it in terms of episodes.”

Although TV critics like Emily St. James have argued that each Part of TP:TR “has a rough episodic structure that helps viewers distinguish one from the other,” one of the only details I’ve seen anyone provide in support of this sort of claim is the basic fact that many of the Parts close with a band performing at The Roadhouse, thus providing evidence of intentional episodic design. As Matt Zoller Seitz writes: “Every episode runs an hour. There's usually a musical number at the end. The thing is very structured. As a TV series.”

Granted, the fact that 11 of the 18 hour-or-so-long Parts end with a band performance at The Roadhouse does at least demonstrate that the choices about how to split TP:TR up into parts were not made exclusively by throwing darts at a dartboard. Yet it hardly undercuts the insistence by Duwayne Dunham and Mark Frost that virtually no thought was dedicated to episodic structure or episodic content in the writing and editing of TP:TR. In other words, all it shows is that TP:TR, despite having been created as a single continuous narrative, was cut into roughly equal hour-long parts to satisfy TV programming needs, with Roadhouse performances slapped at the end of some of the Parts.

(I should add one additional caveat to the above statement that “virtually no thought was dedicated to episodic structure” in the construction of TP:TR. While I do not think this at all undercuts the main point, I think it fair to note that there is at least some evidence suggesting that David Lynch, in line with his long-time obsession with numerology, arranged at least a handful of narrative events in TP:TR such that they fall in specific Part numbers. For example, in Part 3, Cooper finds himself in a strange structure, in a world with a vast purple ocean, where he is faced with two differently numbered electrical outlets: “3” and “15,” matching his Great Northern room number 315. In Part 3 we see him enter the “3” outlet and become Dougie. Later, in Part 15, we see him start the process of exiting his life as Dougie by sticking a fork in a household electrical outlet. It is possible, if not most likely, that these numerical alignments are not coincidental. It is also possible that other examples exist: for example, the Log Lady’s declaration that “Laura is the One” falls in Part 10, a number that elsewhere in TP:TR Lynch’s character Gordon Cole highlights as the key “number of completion.” Yet these types of numerical alignments, to the extent they are intentional, can hardly be called typical of episodic TV series; instead, they are the product of a highly idiosyncratic artist.)

The Example of Part 8

Dunham points to the opening of Part 8 as something demonstrating TP:TR’s lack of concern with traditional TV-episodic form. “I think Part 8 does open with Cooper and Ray just driving along the road forever. A very, very, very slow opening and that’s not how traditional TV would ever open.... Nobody opens like that. You usually have an active opening and a super active ending, but that’s what I’m saying. They were never constructed to be anything other than a continuous narrative.” While I think Dunham overstates the matter (some TV series, like certain episodes of BETTER CALL SAUL, do in fact open that slowly), his general point about the odd structure of Part 8 is worth considering further.

In contrast to Dunham’s belief that the structure of Part 8 helps demonstrate why TP:TR is like a film, I’ve seen multiple instances online of people arguing that Part 8 exemplifies why TP:TR is structurally more like a traditional TV show. For example, Matt Zoller Seitz has written: “The power of ep eight of TP:TR comes from the filmmaking, but also from the break in continuity it represents from the rest of this great series.” And A.B. Allen, in the same viral thread quoted at the top of this post, writes: “This is so far beyond cringe inducing. THE RETURN doesn’t even behave like a movie. That widely acclaimed eighth hour is only as effective as it is *because* of how it sits within a season of TV. Ignoring that this is a series undermines the most interesting things about it.”

What I think these arguments overlook is that Part 8 *does not* merely consist of its widely acclaimed segment, the 40 minutes that begin with the Trinity nuclear test and end with the broadcast of the Woodsman’s dark poem. If it did only consist of those 40 minutes, then perhaps one could rightly argue, as Seitz and Allen seem to, that it shows how an episodic design at a constitutive level—often considered a hallmark of TV shows—is central to the delivery of TP:TR’s themes and story, with particular episodes dedicated to particular themes and story arcs, and intended to contrast and complement other episodes in specific ways. To the contrary, though, Part 8 begins with a full 10 minutes of other material that pick up the main storyline right where Part 7 left off, with Mr. C (Cooper’s doppelganger) fresh out of prison and driving with Ray along the highway; a musical performance by NIN acts as a palate cleanser of sorts before the final 40-minute segment commences. While one can draw a very loose connection between those first 10 minutes and the final 40 minutes—BOB and the Woodsmen make appearances in both, and both are generally dark in tone (although the Senorita Dido segment of the final 40 minutes is beautiful and hopeful)—there is no strong connection between the two segments in either theme or story, and presumably one could draw similarly loose connections between the final 40 minutes and almost any other 10 minutes of TP:TR’s narrative that might have been placed at the beginning instead.

The “break in continuity” those acclaimed 40 minutes represent, then, is not one between consciously-constructed TV episodes, but one between components of TP:TR’s long narrative. And such breaks in narrative continuity are not uncommon in films—e.g., think of the breaks in MULHOLLAND DRIVE, BARBARIAN, PSYCHO, FIRE WALK WITH ME... others can surely come up with even better examples. Part 8 may stand out because it contains that bravura segment, but nothing about the design or placement of the segment indicates that episodic structure, per se, is critical to the way TP:TR’s narrative plays out. If anything, it shows the opposite: that episodic structure is mostly *unimportant* to TP:TR.

Like Dunham, Sabrina Sutherland, the Executive Producer of TP:TR, has emphasized how radically different the process for making TP:TR was from the process for making the two seasons that aired in 1990-91. “[It] was run completely differently from the original. There was only one director. We shot this like a giant film. We shot everything before we edited everything before we mixed everything before we color-timed everything. It was a completely different process and completely different feeling. This was not TV in the usual sense.” While she has acknowledged that some of these production aspects have been becoming more popular in TV production (“I guess in this day, cross-boarding (where multiple episodes are shot at once) and having one director for multiple episodes is not unusual”), she notes that the degree to which TP:TR used these aspects is somewhat unusual (“We just took it a step further and had all 18 hours cross-boarded”), and that it starkly contrasts with the more traditional TV-production approach that was ubiquitous when the two seasons in 1990-91 aired (“This is something quite contrary to television from years ago”).

Filming Every Page of a Novel

While Dunham and Sutherland’s remarks focus on the aspects of TP:TR that make it more like a film than a TV show as traditionally understood, David Lynch and Mark Frost, the two co-creators of TWIN PEAKS, have expressed views that seem to focus more on the blurring of traditional categories represented by TP:TR. Frost, who originally made his name working as a writer and story editor on several seasons of the acclaimed 80s TV drama HILL STREET BLUES, has expressed that he “[doesn’t] necessarily think this is a TV show or a movie.” Instead, given its lack of episodic structure, on the one hand (making it unlike a TV show), as well as its extreme length, on the other (making it unlike a film), he compares it to “filming every page of a novel”—an art form in which he also is well-versed, having written several novels. (He adds that novels “have the the luxury of beginning more slowly... It is not, ‘You have to grad the audience by the throat in the first 35 seconds or you’ve lost them.’”) While the comparison to a novel may strike TV critics as another well-worn cliché used by TV showrunners in discussing the storytelling ambitions of their show, the types of TP:TR’s departures from traditional-TV enumerated by Frost, Dunham, and Sutherland suggest that Frost’s embrace of the “filmed-novel” moniker is actually built upon a more substantive grounding.

Notwithstanding his practice of calling TP:TR "an 18-hour movie," Lynch, for his part, has expressed that the distinctions are somewhat meaningless to him. "Television and cinema to me are exactly the same thing," Lynch has said. "Telling a story with motion, pictures and sound. It ended up being 18 hours." The creative processes, to him, are very similar. "It’s the same thing. You get ideas and you try to stay true to the idea as you translate it to cinema, and back then I saw the pilot as a film and now it’s the same thing. It’s a film. It’s just shown in parts." Contrary to characterizations of him as an anti-TV snob, then, he’s he's not elevating "film" over "television" in these quotes; he's just equating them. In fact, if anything, his quotes in recent years have elevated TV over film: "Television is way more interesting than cinema now. It seems like the art-house has gone to cable." (While he has expressed a preference for theatrical release over home viewing, it is clear that this stems merely from his fixation on the importance of high, immersive sound and picture quality to a viewers’ experience.)

TV, The Medium

These Lynch quotes on TV versus film are illustrative of a phenomenon that has plagued these types of discussions: they elide the differences between TV, as a medium, and TV shows, as an art form. That not everything that airs on TV is a “TV show,” nobody seems to dispute; people seem to have little problem acknowledging (in most cases, at least) that movies do not become “TV shows” simply because their first (or primary) release occurs on television or streaming services. Yet aside from these clear-cut instances of films on TV, there is a tendency for almost everything else that airs on television to be lumped together into an amorphous pile and labeled as a “TV show.” Looking at the “best TV show” lists compiled by major outlets from the past several years, one finds works structured in all manner of forms; from the standalone-anthology-installments of BLACK MIRROR, to the small-sketch-based KEY & PEELE, to talk and variety shows like THE DAILY SHOW, to the short and uniformly-produced FLEABAG (whose seasons, as a whole, have shorter running times than many of the films on the Sight and Sound list), to mostly non-serialized episodic shows like THE SIMPSONS, to the now more-ubiquitous serialized episodic shows like BETTER CALL SAUL.

What do all of these works have in common, apart from airing in segments on television or streaming services? Very little. The mere fact that a work has been cut up into smaller units—absent anything further—does not seem as if it should be significant in itself for purposes of classifying its artistic form. Indeed, anything can be cut up into pieces (as is often pointed out, many classic novels were originally released serially). The important question in this regard is seemingly whether a segmented structure is important to a work’s goals, to its design, to its identity; and if so, then how so. Yet even among TV critics, the fact of works’ original release in the medium of TV is often held to be more salient for purposes of comparative analysis than the formal artistic (sub)genres of those works airing on TV, of which there are seemingly multiple widely divergent ones, as seen above.

Indeed, the term “TV show” itself does not seem to reflect a coherent formal artistic genre, but rather merely to be an expression of a work’s existence in the medium of TV. Part of the conflict over TP:TR’s categorization seems to stem from Sight and Sound (and possibly other film-world lists, like those of Cahiers du Cinéma) making rankings apparently based on formal artistic genre, whereas many of the TV critics’ big-tent rankings seem to be based more just on the medium of TV. There are valid reasons for taking either approach, but we should be clear that comparisons of the two are not apples-to-apples, criteria-wise.

Unitary Authorship, or Auteurism

Apart from the issue of segmentation, and how a work utilizes it in both its structure and its production processes, one of the other main factors people seem to sometimes employ in assessing how a work like TP:TR should be categorized is the extent to which it has unitary authorship, or what we might call its degree of auteurism. The works on the Sight and Sound list of the “greatest films” all (as far as I know) are directed & written, in their entirety, by a single person or set of people, something that distinguishes them from TV shows where each individual installment is typically written and directed by different people than the next installment. (I realize that “auteurism” is typically used in film writing to refer specifically to the work of directors, but given the elevated status often accorded writers over directors in the world of TV shows, I use the term here to jointly refer to director(s) and writer(s) on a work, and acknowledge the problematic aspects of assigning sole authorship to one or two people out of the dozens or hundreds of artists & craftspeople who contribute on any given motion picture.) Here, unlike the two seasons that aired in 1990-91 (and the majority of TV shows), TP:TR is more like the films on the Sight and Sound list, insofar as it is entirely directed by Lynch and entirely jointly written by Lynch & Frost.

Comparing TP:TR to something like THE SOPRANOS, one of the consensus greatest TV shows of all time, is perhaps instructive. TP:TR differs from THE SOPRANOS on three of the major fronts we’ve been discussing: (a) unlike THE SOPRANOS, episodic form is of little importance to TP:TR’s structure; (b) likewise, its production processes were focused on one single entity, the work as a whole, rather than being segmented into individual productions for each episode; and (c) it was entirely directed by the same person, and jointly written by the same two people. Even so, TP:TR is similar to THE SOPRANOS on two major fronts: it is much longer (at ~16.5 hours) than a typical film, and its narrative builds on earlier seasons of a TV show.

Are these two factors—length, and what might be termed narrative contingency, i.e., a story that builds on top of prior installments—sufficient to make it inappropriate to consider TP:TR a film?

Narrative Contingency

Addressing the issue of narrative contingency first: it’s not uncommon for works widely considered films to have some degree of narrative contingency as well. Sequels exist, for one thing; to use an obvious example, THE GODFATHER PART II, #104 in the Sight and Sound ranking, has a story every bit as contingent on previous work as TP:TR. To be fair, the Sight and Sound rankings have, over time, differed in how they have treated sequel films. Starting in 2012, a rule change was implemented that prevented ballots from counting the Godfather film series as a single choice, with an explanation provided that this was being done “since they were made as two separate films.” Note that even prior to 2012, though, the Sight and Sound lists did not reject the Godfather works as “film”; rather, they merely considered them to be one single film, rather than multiple ones, notwithstanding their segmented nature. (However, the choice to consider only parts I and II, specifically excluding the third installment, as a single film ranking #4 on the 2002 list, seems dubious.)

Even some non-sequel films, such as adaptations, those based in true stories, and heavily allusive works, often build upon a preexisting knowledge base expected to be shared by viewers; and every work, to some extent, is created against an assumed backdrop of viewers’ knowledge of society, and of other works in the same genre. Most relevantly for the purposes of classifying TP:TR, consider the film TWIN PEAKS: FIRE WALK WITH ME: it is this work, not the two TV seasons from 1990-91, that acts as the immediate predecessor in release to TP:TR. Notwithstanding FWWM’s relative narrative contingency on those two TV seasons (even though it is mostly a prequel, it is generally recommended to watch those two TV seasons first, given that its story draws significant resonance from its relation to those other works), it is not considered very controversial to call FWWM a film, and its #211 ranking on the Sight and Sound list has drawn little objection on that front.

Media organizations engaging in critical TV show rankings have taken conflicting approaches to classifying TP:TR’s relation to the TWIN PEAKS works from the 90s. For example, the 2021 BBC Culture ranking of “the greatest TV series of the 21 Century,” based upon a poll of 206 “TV experts - critics, journalists, academics, and industry figures,” limited its list to series that began in or after the year 2000. As such, THE SOPRANOS, whose first series premiered in 1999, was excluded from the list, despite the bulk of its episodes airing in or after 2000. Curiously, however, TP:TR was allowed on the list, and ranked #13; presumably, if one views TP:TR as the third season of a single TV show rather than a standalone entity, then it should have been disqualified from the list, like THE SOPRANOS.

(By similar logic, one can argue that TP:TR should not have been permitted in the “Limited Series” categories at the 2018 Emmy Awards, as the Emmys defines a Limited Series as a “complete, non-recurring story.” It mattered little, though, as—in slates that typify the ungainly mess that is TV categorization—Lynch’s work on the entirety of TP:TR lost the Limited Series or Movie directing Emmy to Ryan Murphy’s work on a single episode of THE ASSASSINATION OF GIANNI VERSACE: AMERICAN CRIME STORY, and Lynch and Frost’s work on the entirety of TP:TR lost the Limited Series or Movie writing Emmy to Charlie Brooker and William Bridges’ work on USS CALLISTER, a 76-minute episode of BLACK MIRROR that was classified at the Emmys as a TV Movie. Meanwhile, TP:TR failed to even get a nomination in the overall Outstanding Limited Series category for which it was submitted, being edged by GENIUS: PICASSO, GODLESS, THE ALIENIST, PATRICK MELROSE, and the winner, Murphy’s ...VERSACE....)

Like the BBC Culture ranking, the Dec. 2019 Rolling Stone list of the “50 Best TV Shows of the 2010s” treated TP:TR as a standalone work, ranking it #14; again, if it had been considered the third season of a TV series, it should have been excluded from the list, this time due to the list’s stated rules that, to qualify, the “majority of [a show’s] episodes had to have aired in this decade.” By contrast, the 2022 Rolling Stone list of the “100 Greatest TV Shows of All Time” grouped TP:TR in with the 1990-91 seasons of TWIN PEAKS and considered them a single, three-season show, ranking it #16. FWWM was excluded from this grouping, a choice that also shows the disorderliness of these types of TV-based categorizations, given the fact that FWWM is at least as connected to the narrative of the 1990-91 seasons of TWIN PEAKS as TP:TR is (and arguably more so, given that its production followed sequentially the year after the second season completed).

Does Size Matter?

As to the issue of length, it’s worth noting the diversity of “film”-sizes that have appeared in the Sight and Sound rankings: not only other longer works, like OUT 1 (720 minutes, #169 in 2022) and BERLIN ALEXANDERPLATZ (894 minutes, #202 in 2012), but also short films like MESHES OF THE AFTERNOON (14 minutes, #16 in 2022) and UN CHIEN ANDALOU (21 minutes, #169 in 2022). TP:TR thus fits squarely within the broad, length-insensitive definition of “film” reflected in the Sight and Sound list.

It is fair to note the ways in which a 1000 minute film offers much greater chances for character, thematic, and story development than a 100 minute film, and the ways that a 1000 minute running time also presents different challenges as to how the work might be cohesively structured than a 100 minute running time. Similarly, though, one might equally note the myriad ways in which a 10 minute film presents very different opportunities for (and challenges to) structure and development than a 100 minute film.

Yet the appearance of the 14 minute MESHES... at #16 on the Sight and Sound list has kicked up nowhere near the fuss of the appearance of the nearly 1000 minute TP:TR at #152. One does not see viral Twitter threads painting those who included MESHES... on their Sight and Sound ballots as “people so embarrassed to adore [short films] they have to rewrite definitions to accommodate their own insecurity.” While one might argue that the comparison is inapposite, since “short films” are by their very name “films,” this seems mere verbal contrivance; the substantive issues remain.

Nor do I think it persuasive to argue, as many have, that the thing that separates TP:TR from true “films” (yet would not similarly distinguish short films) is that one cannot watch it in one sitting. First of all, as a mere technical matter, this is not true. While watching literally in one unbroken viewing is challenging (albeit doable), this is usually not the standard we hold and film or even TV shows to, given that bathroom breaks and the like are common for anything. And, at any rate, a number of fans have discussed their marathon single-day viewing sessions of TP:TR, encouraged by things like Showtime’s occasional marathon airings of the entirety of TP:TR on one of their channels. More importantly, “number of viewing sessions required to finish” seems like a pointless way to define a formal artistic genre, and one that rings particularly hollow given the rising prevalence of film lovers streaming movies at home in segments over the course of two or more days. (For example, after its 2019 release on Netflix many people online discussed watching THE IRISHMAN’s 3.5 hour running time over three or more viewing sessions, a breakdown that at least superficially matches MoMA’s theatrical airing of the entirety of TP:TR over the course of three segments on Fri/Sat/Sun in 2018.) Speaking from my own personal experience, the majority of films I've watched in the last three years have been at home, viewed in multiple sessions over the span of two or more days.

A TV Long-Form Film

Notwithstanding the above considerations, I do think it is fair to say, per Mark Frost’s quotes about TP:TR’s novelistic qualities, that the length of a work affects its artistic possibilities, a point reflected in the literary distinction between novels, short stories, and novellas. It therefore seems reasonable to question the appropriateness of classifying filmed works of drastically different lengths in the same formal artistic (sub)genre. Even if one declares TP:TR to be something other than a traditional feature film, though, the upshot is not that TP:TR should be considered a serialized TV show like THE SOPRANOS. After all, the major distinctions between the two works, as discussed earlier, still remain. Rather, it would seem more appropriate to create a new moniker – long-form film, perhaps, as opposed to feature films and short films. Given their length, these long-form films will usually air first, or only, on TV or streaming; this does not thereby convert them into a serialized TV show, but it does make it fair to call them a type of TV film (referencing their use of the medium of TV). Moreover, I think a recognition of the qualities that make it natural to think of long-form films as a formal artistic subgenre of films themselves might yield a surprising conclusion: it would actually be demeaning to and snobbish towards the medium of television for prestigious lists like Sight and Sound to NOT recognize works like TP:TR as films, merely because they air on TV.

Long-form films could possibly be defined as follows: (a) unitary authorship, i.e., their being wholly written and directed at each and every step by the same person or small set of people; (b) a non-episodic narrative (thus something like DEKALOG, with its sharply episodic, anthology-like narrative, would not qualify), where being broken into installments for the purposes of airing is not disqualifying in and of itself; and (c) a length substantially longer than a typical feature-length film – to pick a specific limit, let’s say at least 4.5 hours long, which would exclude most of the longest theatrically released feature-length films (like A BRIGHTER SUMMER DAY, at 3 hours 57m). Some may wish to loosen these criteria; it’s worth noting that of the three works Emily St. James highlighted in 2017 as having similar degrees of auteurism to TP:TR (BETTER THINGS, THE YOUNG POPE, and TOP OF THE LAKE: CHINA GIRL), none of them meet these three criteria as stated. A more fulsome attempt to analyze the growing film-like aspects of long works airing on TV and streaming would need to grapple with these examples, as well as numerous others, such as CARLOS, TOO OLD TO DIE YOUNG, RIGET, and THE KNICK.

As boundaries continue to blur, hopefully film awards and rankings like the Oscars will, following the lead of the Sight and Sound list, open eligibility to long-form films, perhaps in their own category. As is, the Oscars limits many awards to films released in the medium of theatrical screenings, but it permits short films to qualify by screening at a “recognized” film festival, a type of hoop-jumping that feels needlessly arbitrary in a world where anyone can watch almost anything, at any time, at home.

There is no way to get rid of the inherent messiness of any attempts at categorization. (For example, some movies display elements of episodic structure: PULP FICTION, for example. Curiously, PULP FICTION is the same length as FLEABAG Series 2; both are broken up episodically; and both have unitary authorship. The prime formal differences are just that FLEABAG aired on TV, and has some narrative contingency on a previous series. Basically, though, there is a strong case for them belonging in the same formal artistic genre.) Lines will inevitably be blurred, works will inevitably straddle categories. And that’s fine. There needn’t be a binary between individual categories—it should be fair to use multiple categorical terms to apply to a single work, to the extent it exhibits such varying characteristics.

And at least one of the categories that should apply to TP:TR is that of a film. A long-form film, airing on TV.

POSTSCRIPT: I'd like to add a note of regret concerning a tossed-off tweet of mine on this topic, which you can see below, that received a moderate amount of attention on Twitter. (1) It uses a broad brush to seemingly paint as whiny all TV critics who objected to TP:TR's classification as a film, which is neither kind nor accurate; in fact, a number of critics, including some quoted in this piece, set forth thoughtful and principled analyses which carefully considered the reasons and ambiguities of the situation. (2) It also flippantly uses a broad brush in critiquing the reception of TP:TR by TV critics, when in fact it was broadly praised and championed by numerous TV critics, including those quoted in this piece. While I do take issue with the ways some critics addressed TP:TR, I regret making such unfair, broad generalizations.

#twin peaks#sight and sound#david lynch#mark frost#twin peaks: the return#tv criticism#film criticism#long-form film

19 notes

·

View notes