#featherwork

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“Feathers: A Transcultural Art History”

Friday, February 28, 2025 - 9:00am to 5:00pm

Free and open to the public. No registration required.

Loria Center for the History of Art, Yale University

The feathers that birds create have long appealed to human makers. Feathers are structurally strong while giving the appearance of delicacy. They can be vibrant or muted in color, matte or iridescent. They are found everywhere that birds are found, which is to say, across the entire globe, and have given rise to feather art traditions that respond to material commonalities while also imbuing feathers with varying values, social roles, and aesthetic affordances.

Central to most of these traditions is the understanding that not all feathers are created equal. The feathers of certain rare birds have been ascribed economic value equivalent to that of the rarest mineral pigments, while others are understood to hold sacred value. The connection of a feather with the living body of the bird who formed it, even after their separation, is often perceived as central to the liveliness and agency of the feather itself.

Feathers have been incorporated into garments and accoutrements for the body, into sculptures, and into works that resemble paintings. They have been used as tools, objects of trade, and expressions of power and faith. The harvesting of feathers for human creation and consumption is also part of a larger history of extraction and violence, even in the case of cultures that venerated birds themselves as sacred beings.

The aim of the workshop is to address the art history of the feather across time and place, bringing studies on the role of feathers within particular artistic traditions into conversation with one another. Ranging from the Americas to Europe, Asia, and the Pacific, our goal is to stimulate an expanded, transcultural understanding of the feather’s affordances as a medium, and of the commonalities and differences in the ways that feathers have inspired makers from antiquity to the present.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Creative Art with Photoshop.

0 notes

Text

Inspired by a question to the oracle, here is my current work in progress, a cardigan for my husband. I’m on my third attempt. After knitting mile after mile of navy, I’m about ready to throw it out the window. I’ve made a spreadsheet of line by line stitch counts, and it’s been well, even more tedious, but helping. I can’t wait to get to the colorwork! This time for sure!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Devastation, regeneration, transformation.

(this is very vague interpretation and my personal thoughts how did happen olrox's first transformation into Quetzalcoatl)

(A bit more of the talking and inspirations under the cut)

+ my favourite shots!

So for some time I've been speculating about Olrox's backstory (you can find some bits in my latest post, but much more is inside my head), and at some point I was thinking about his turning into a vampire. In what circumstances did it happen? What was the motive of Spanish who turned him? What was Olrox's own attitude to it? So many thoughts and possibilities...Then I saw this statue of Quetzalcoatl and got really inspired to learn animation just to draw Olrox's first transformation to his feathered-serpent form; I loooove when transformations are a bit quirky and have tried to depict it.

I left the whole scene a bit vague, so everybody can interpret it in their own way (please share your thoughts!!) but something here is clear: the vampire who turned him is very much dead + I was thinking how blood could be connected to his changing of form, so it is very present here. I also took some freedom with the image of Quetzalcoatl on the mural, but I've based him slightly on the figure of the Feathered-Serpent on the Acuecuexatl's stone , and added featherwork because I think it is magnificent and I love it very much.

#i really learned how to animate just because of the 2d character. it is this bad guys#what the next stage i wonder#art#my art#animation#wow baby's first#castlevania#netflix castlevania#castlevania fanart#castlevania nocturne#castlevania nocturne fanart#castlevania nocturne s2#olrox#olrox castlevania#olrox fanart#olrox castlevania fanart

684 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHENAHYEIGI FUNERAL PRACTICES AND ANCESTRAL VENERATION: AN OVERVIEW

---

FUNERARY PRACTICES

All dead must be cremated to be properly sent off. Their soul will remain in their body unless and until this is done, and a soul that remains trapped without rites may wander as an incorporeal evil spirit, or reanimate into an even more dangerous physical one. Community members will be given the most lavish funerals, but unidentified people found dead or even enemies slain in combat will usually be cremated (if only to prevent consequences from their potential vengeful spirit in the case of the latter).

A recently dead person still has their unaltered soul in their body and their senses are intact, and their body is not considered unclean to touch until it begins to noticeably rot. Their eyes will be left open so they can see what's going on around them (though they will be closed immediately preceding cremation, if possible). They will be visited by friends and family to say goodbyes and are spoken to and held and touched during this period. They are washed, freshly clothed, and wrapped into a wool blanket until the funerary preparations are complete.

Funerals should ideally be performed within three days of passing at most, and most people in the clan will cease their other duties to focus on preparation and gathering firewood. Oak is relatively abundant in most of the Highlands below the treeline and is the fuel of choice for pyres. Most Chenahyeigi peoples readily use dry cattle dung as fuel for everyday fires, but do not share the Wardi approval for using it for cremation and will not do so for honored individuals unless in desperation.

A form of animal sacrifice plays a role in funerals here. When someone dies, they are sent along with some of their clan's livestock (and potentially guard or herding dogs) to ease the transition and add to their ancestral clan’s wealth in the afterlife. The amount and type of animals offered depends on the person’s status, and upon the wealth of the clan. Offerings of khait are particularly special and often reserved for only the most honored dead. These animals are slaughtered and butchered in the typical fashion, and only their hearts (vessel of the soul) are cremated. Their remains can then be freely eaten (usually winding up in part as a funerary feast) and used for material.

Other grave goods are important as well. The dead should always be burnt in their finest clothing and jewelry. Food and drink will be added to the pyre to provide sustenance on the way to the afterlife. Most Chenahyeigi peoples who believe the dead take the form of birds will place eagle feathers into the dead person's hands to assist in the transition, with some high status individuals being cremated in featherwork shawls. They should also be presented at their funerals with any tools they needed in their daily lives, and any other belongings that were precious to them and not intended to be passed down. These objects are not typically burnt and rather will be interred in clan ancestral shrines.

The body must be completely burnt until only bones remain. Once this is accomplished, the soul will rise with the smoke and begin its journey to the Celestial Fields, the great landscape behind the stars and the site of the afterlife. In all traditions, the dead will be guided and assisted by their ancestors in this journey. Some traditions hold that ancestors teach the dead secret magic to become an eagle and fly there, others believe that the dead are merely assisted by birds at their ancestor’s behest. A few instead believe that the dead are carried by the cattle of the gods Hraighne and Od during their daily journeys through the sky (Hraighne and his sons are the sun and moons respectively, Od lives on/is symbolically the earth).

In the process of traveling to the Celestial Fields, you'll pass through the land of two divine clans. The gods Ariakh and the king of eagles have pasture on the tops of mountains and the lower skies, while the land of Hraighne and Od is the earth and the Fields themselves. The importance of these deities to funeral rites varies heavily by tradition. In most cases, funerals just require the pouring of libations to each deity to request safe passage through their lands. In others, the gods can be personally entreated to act as guides, and funerals require an additional array of failsafe rites to guarantee that the dead retain their favor. Hraighne and Od tend to be most important funerary gods, as the afterlife is their land and they are also often elevated above other deities as the first ancestors and the beginning of all male and female ancestral lines. If you fuck up so badly that you've offended all of your named ancestors, you still potentially have their favor and assistance.

After full funerary rites have been completed, the dead are regarded as having no further connections to their bodily remains and no need of them whatsoever. These cremains are also regarded as mildly unclean, and have no further interactive purpose for family members either. The bones are typically buried in nondescript locations, usually far away from a clan’s land. This is in part due to beliefs that the empty human remains still carry a bodily connection to their blood kin, and can be tampered with in malicious capacities to inflict harm on the living. Burying them in nondescript, distant locations reduces this threat.

---

OFFERINGS AND ANCESTRAL SHRINES

Intercession with the dead centers around actions of the living and maintenance of shrines. The dead now live in the Celestial Fields. The Fields have been provided with heavenly cattle by the goddess Od to ensure that the dead never starve (the cattle offer a perpetual supply of milk), but no mortal Owns these cattle. They belong to Od and are guarded by the dog Mak-Urudain, and the only person who has ever successfully stolen cattle under his watch is Ariakh. A mere human doesn’t stand a chance. Rather, the dead live in clan systems like they did in life, and require crops and wealth in livestock to thrive, and quality goods and tools to be truly prosperous. They are dependent on the living to provide these things.

Some livestock and other supplies will most likely have been provided at the funeral, but the dead will be continuously gifted additional offerings in the time after, by leaving them in the ancestral or household shrines. Small offerings of food, flowers, and grain are burnt to send them directly, while more valuable offerings are left in the shrines for the dead to collect upon their periodic returns to the world of the living.

All discrete objects have spirits, even manmade/inanimate ones (which have the simplest type of spirit, not a consciousness but an essential force that makes them ‘alive’, capable of imbuing life into other objects and working magic). The dead, having departed from the body, can take the incorporeal spirits of offered objects with them for use. After this point, these objects are considered ‘dead’ and cannot fulfill their full purpose for the living. Sure, a dead loom could perform its material functions of weaving, but dead objects can only create more dead objects, and dead objects are unlucky to touch anyway. On top of that, objects whose spirits have been taken by the dead represent a line of contact between the living and dead. It’s a minor desecration to use the body of an object belonging to an ancestor, and it will gain their disapproval.

In times of dire need, the dead may deign to return an objects spirit for the living to use again. In most Peoples, the negotiations require the intercession of a witch, who is uniquely equipped to mediate with the spirits of the dead and read signs of their approval or disapproval. If the ancestor approves, they will return the objects spirit to its body and it will become alive and viable for use again.

A clan's ancestral shrine in of itself is usually a large above-ground mausoleum, containing numerous smaller shrines for each of the clan's dead. These individual shrines are maintained for a set number of generations (typically twelve generations counted in 20 year periods) before the objects within are permanently interred in burial and the person is no longer obliged further offerings. These dead have passed into an elder status and join the ranks of ancestors unnamed. They have presumably been cared for properly by their descendants, are well-set up in their afterlives, and no longer require direct intercession from the living for their benefit. The retirement of these shrines take the form of a second funeral (long after the last person to have known them has died) where all objects within are buried on the clan’s land.

Even after passing into the ranks of ancestors unnamed, old dead still have some representation in ancestral shrines. Clans maintain a beaded rope (with a new bead added for each death) within the shrine, as a means of record keeping and an object that can be easily carried should a clan lose or have to flee their territory. Very old clans might have beaded records of hundreds of dead, and it serves as a visual reminder of the great scope of a family and its ancestral lines.

Shrines may have valuable items tempting to thieves, so they need permanent guardians. Bone or wood carved figurines of guard dogs are usually utilized for this purpose and enchanted into sentience by calling a minor wild spirit into it. One figurine will be made for each individual shrine. Most traditions also involve interring the skulls of actual deceased guard dogs in ancestral shrine mausoleums, so that the same animal continues its duty in death.

Consequences of theft from ancestral shrines are grave. You will, first and foremost, provoke the wrath of the dead. They may curse the thief, which can cause devastating ill fortune or disease. Your own ancestors are likely to be insulted by your shameful behavior and may inflict their own punishments as well. The guard dog spirits will also take vengeance. They are believed capable of pursuing the thief and haunting them until the theft is amended, causing night terrors and additional ill fortune, (or potentially even just killing them, you never know). Underlying the spiritual dissuasion of theft is hard material and social consequences- stealing from another clan’s ancestral shrine is a serious act of desecration, and is accepted as generally warranting a blood price (severing fingers, a hand, an arm, or just killing them, depending on the severity of the theft).

Destruction and raiding of enemy's ancestral shrines is not unheard of in warfare, but this is generally considered a 'nuclear option'. Some people may see it as a deserved consequence for a detested enemy, but it is catastrophically risky behavior, creating both mortal and immortal enemies. Stories about people who do such a thing in war tend to end in their annihilation (if not that of their clan itself) via the consequences of enraging an entire ancestral clan. In reality when this occurs, it tends to cement permanent enmities that can last for generations, and is at least cited as reasons for long-held hostilities between entire tribes.

Clan ancestral shrines are a separate entity to the household shrines where most everyday religious practice is held. Each home will have a dedicated shrine area where each of the family’s ancestors and other honored dead are interceded with on a daily basis. Much of this comes in the form of offerings, burnt or left in bowls. Minor day to day offerings are small items that will be of utility or sentimental value to the dead, usually libations of milk/tea/wine, grain, flowers. or small gifts. These daily offerings are less about actively sustaining the dead and more about sustaining your connection with them.

— FEAST OF THE DEAD

Major offerings occur on set holidays, most importantly the winter solstice feast of the dead. Individual ancestors may make the journey down to earth throughout the year as they deign fit, but on the longest night of the year, all dead make this journey at once to mingle with the living again. This is a joyous and festive occasion- it's a time to celebrate the lives of both the living and dead, reconnect with loved ones, and have a lot of good food and drink.

In the days leading up to the holiday, you should clean and decorate your home. It's a good time to restore protections against bad luck and malicious spirits for your community in general- people sprinkle milk around the entrances of homes and of the village itself, hang fresh iron bells over doorways, and clear any present snow from pathways. Communities will have stored food for months in advance, and now have to cook it all in preparation. The leading clan must send out envoys throughout their land and provide high quality foods (particularly yachuig, which is rendered grain-fed khait fat mashed with honey and berries and chilled) and wine to their constituents (or else lose dangerous amounts of respect and social capital via their inability to gift). The cattle and horses are usually nearby the village in their winter pastures. Some should be slaughtered for the feast, and the finest animals in each herd are cleaned, brushed, and decorated.

Lead cow in her party clothes.

The night before the solstice, you set up and tend bonfires around meeting points in your village, and place candles in the windows of your home. The dead have started their journey at this point, and this makes it easier for them to find you, as well as providing light and protection during the night of the sun's longest absence (Hraighne is having a prolonged visit with his wife; they're separated the rest of the year). It's best that you go to sleep early (or if you get stuck on bonfire duty, that you establish strict sleeping shifts), as you will probably be awake for the entire night that follows.

The dead arrive at high noon on the winter solstice. Everyone should convene at their respective clan shrines (or a household/temporary shrine if you are traveling or live away from your clan). There, the dead are greeted with offerings of warm clothing to wear during their visit (as it's much colder here than in the Fields). This is also the time to give the dead major offerings as gifts. These are items of value that members the clan has obtained/created over the course of the year, whatever any given family is willing and able to give (wool, yarn, looms, staffs, artwork, saddles and tack, bows, swords, musical instruments, clothing, etc etc). These objects are to remain in the clan shrines and to not be used again, and are under similar restrictions as funerary gifts. Livestock that were slaughtered for the feast will have their hearts cremated, so that their souls can be sent as further gifts.

The titular feast is usually held as an entire village, with multiple clans assembling together to lay out a full meal. The meal is left out all night for the dead to eat while the community mingles and drinks tea and wine. The dead are present and listening while they eat, so it’s a good time to keep them updated on events via each family member announcing updates about their life and accomplishments from the past year. Anecdotes are told about remembered dead relatives, and stories are told about more distant ancestors. The conversation doesn't have to remain strictly about the dead, and the atmosphere usually becomes very casual, being a good time to catch up with your living relations as well.

The feast goes untouched until the first light of dawn, at which time the dead will have finished eating the spirit of the food and the living can start to eat the body. The spirit of this food has been consumed, and it is thus conceptualized as less nourishing (the fact that the food has gone cold by this time works as a symbolic reminder of this), though it’s still enjoyable enough as a substantial feast. The dead depart again at high noon, and the festivities end with consumption of freshly brewed butter tea before the living depart to catch up on sleep.

This festival is a distinctly happy and celebratory event, but has a solemn side, in being the best time to deal with earthbound ghosts. It’s not unheard of for people in your community to go missing and never be found, owing to rough terrain and people frequently spending long periods alone at pasture. Such a person never gets funeral rites, and is thus trapped as a ghost and likely to warp into an evil spirit. This fate is not only tragic and distressing but can also become dangerous for loved ones; a ghost might return to haunt them, causing illness and other misfortune, or occasionally more immediate corporeal danger.

The feast of the dead provides an avenue to potentially retrieve and save such dead, which is the job of the community’s witch. Witches do not join in the nighttime festivities, and rather must spend the night in vigil to call in the wandering dead and send them on their way. Anyone in the community with a missing relation will provide the witch with a straw doll in advance. This will contain a lock of the presumed deceased’s hair (locks are typically saved from haircuts for a variety of other medicinal and magical purposes) or one from their blood kin if this cannot be found. This doll will become a substitute body that can be cremated.

A witch has their own additional non-blood ancestral line, being the many generations of witches before them, leading up to their own mentor. These ancestors return with all the other dead, and will join the living witch for their vigil and assist in their duties. They then set a bonfire outside the boundaries of the village, place the dolls around it, and wait for sundown.

At dusk, the witch will begin a summoning song, calling the names of any known ghosts and attracting them to the fire. Other earthbound human spirits of unknown name may also wander in of their own accord. The witch then does a form of battle with these ghosts- these entities are dangerous and may try to possess or harm them, or to slip past the bonfire to enter the village to wreak further havoc. The witch paces around the fire and beats the drum (closely related practice to Wardi heartbeat drums) while singing commands and directions to the ghosts to settle into their doll body. They point the dagger into each doll with each pass, which may force the spirit inside. Their witch ancestors are also present in intangible form and are doing the same thing all around the boundaries of the village, guarding it in its entirety. The witch must attempt to keep this up all night, and will usually chew the stimulant bruljenum leaf to assist in the process. Most witches have mentees in-training that will provide additional support and potential backup.

Come sunrise, any evil spirits have either been driven away or driven into their doll bodies. The witch then burns the bodies to send the souls to the afterlife, and their witch-ancestors leave, assisting the dead in their journeys. They then must perform an exhaustive reading of the sky, first to see which dead have been saved, and then to gain information on how to assist any that have not (divining requests from the restless dead that may help them come to peace, or possibly the location of their remains). At the end of this exhausting endeavor, they descend to the village to announce the results and join into the feast. They are rewarded with saved portions from the meal and the very first serving of hot butter tea.

Witch of the Sidraste Chen Pyliad People in the midst of the vigil. Most of her clothing is just standard cool weather wear, but the featherwork skirt around her waist marks her station and is worn for special occasions when confronting evil spirits is required. It's made with dove eagle feathers, which are uniquely viable for the purposes of protection and banishment. It is forbidden to kill any birds of prey, and as such it may have taken years to accumulate the feathers for the skirt via searching beneath nests, removing them from found dead birds, or trapping dozens of live eagles and plucking small amounts of feathers from each. This is an incredibly precious garment and must be preserved with great care so that it can last many generations.

—

DAY TO DAY ANCESTRAL VENERATION

An person’s most important ancestral connections are their parents, all of their grandparents, and 12 further generations of their direct male and female lines (their father’s father's father et all, their mother’s mother's mother et all). These are the ancestors that you are directly responsible for assisting in the afterlife, and the ones that will maintain a close connection to you throughout your life.

This bond is the bedrock of your identity, the ultimate support system that is present throughout your life, a home no matter where you are. Your ancestors will provide you guidance, can grant you good fortune, can protect you and your kin, will assist in the births of your children, and will eventually help you reach the afterlife. In return, you honor them (and your living family), give them offerings in support, better your and your clan's positions, behave virtuously and observe taboos. They are to be venerated as a matter of filial piety, but they are just people (not omnibenevolent) and will (usually righteously, sometimes pettily) punish misdeeds or the neglect of their wishes. Many misfortunes experienced in life may be signs of their disapproval.

Respect for the dead is obligatory, most importantly for your ancestors but also just in general. It's a matter of both virtuous behavior and personal safety, as the dead might be listening and there can be consequences if they are offended. Of course, not all dead people are owed obligations of filial piety, or considered to be respectable people in general. Speech avoidance taboos regulate some of these dangers. You should NEVER speak the names of people believed to be earthbound evil spirits except under very specific circumstances where you are under strong spiritual protection (or are a witch and equipped to handle these dangers), as this may summon them to do harm. Ancestors and other dead who have reached the afterlife can be referred to by name, but you should not do so if you don't want their attention, especially not if you're speaking ill of them. If you need to talk about the dead in any of these potentially dangerous ways, you speak of them obliquely 'the old man' 'the one who died last year', 'that old bastard' etc. The word 'eshe' is used almost exclusively in the context of speech avoidance, with the meaning being roughly 'that one'.

Your responsibility is towards your ancestors, but all honored dead are recognized in practice. Your clan's ancestral shrine will also be the place for grave goods and offerings to non-ancestral dead- namely children or people who died without children. A person may additionally leave offerings for dead friends or non-ancestral family, or seek guidance from renowned historical figures.

Family records in general tend to be very well kept, in part to avoid exclusion of people who end one line or the other (one line effectively ends if a person does not have Both male and female children, or if they don’t have children at all). Such people near inevitably will not get as much support from the living, and the fact that dying childless threatens your prosperity in the afterlife is a soft pressure that strongly encourages having many children (in addition to harder societal pressures, and some very material subsistence practicalities). Record-keeping is predominantly through oral transmission, and usually supplemented by pictographic or other visual memory aids (the Chenahyeigi language has no native writing system, though some groups have adopted + adapted Wardi syllabic script or have individuals literate in it, and keep written records).

The practice of tattooing the arms with abstractions of 30 ancestors (your parents, all four grandparents, and your 12 person male and female lines beyond that) is partly such a mnemonic device, but more importantly an act that ritually solidifies one’s place in their ancestral lineage. A child secures their place in this lineage upon coming of age (15 in boys, menarche or 15 in girls), and bearing these tattoos is the marker of adulthood. They were under the Protection of these ancestors beforehand (via their parents), but are now equipped to be active participants in interactions with the dead on their own terms.

Young adults will likely already have learned the names of their ancestral line by this point, and if not, they'll be learning them now. Most people memorize their names by heart by looking at/touching the tattoos as they recite, and will often habitually continue to do so long after the memory aid is unneeded.

You don't have to leave offerings for your ancestors every single day, but you should be naming them on a daily basis as a matter of honoring them and maintaining your connection. This is usually performed in the form of a nightly prayer, where you will recite the names, leave any offerings, and make any requests for guidance or assistance needed at the time.

Your full name is your given name, those of your parents, and your 26-person total ancestral lines (some traditions include All grandparents, bringing the grand total number of names to 30), as well as the name of your clan. It's not even slightly necessary to recite all this in casual introductions, but reciting the entire list is necessary for some formal and ceremonial occasions. You will reintroduce yourself to your community by your long name upon coming of age, will state the whole thing during your marriage ceremony, you and your spouse will recite both of yours when formally naming your child, and others will recite it for you at your funeral.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Don Diaries

During dinner, Dani tells Don and Matteo about her job and asks them all about life on the farm.

Don can't take his eyes off her. His heart aches when she makes Matteo laugh with crazy stories of what Mr. Corn has been up to in the city, and he wants her to stay forever, to be a part of this family.

He manages to keep mostly chill during the entire meal, even when Dani asks a few subtle questions about whether it ever gets lonely out here. Thankfully, Matteo gets into the New Year spirit and starts throwing confetti.

After dinner, they watch the countdown to midnight. Woofer is tired and a little confused about why everyone is awake way past normal bedtime. He hopes this won't become a habit.

Finally, it's midnight, and Matteo insists that Dani tucks him in.

She's very happy to do so, which suits Don just fine. He has a surprise to prepare.

Matteo falls asleep almost instantly, and Dani comes back down. Don is ready.

Dani is thrilled, no one ever gave her flowers before - but what's this?

She reads the card. In a few simple sentences, Don bares his heart, lays out his feelings, and asks her to be his girlfriend.

It's a very enthusiastic yes!

With that yes, Don has completed his Serial Romantic aspiration, and is finally able to leave his old ways behind him for good.

This calls for celebration, although they're both too tired for actual fireworks tonight. Featherworks? It doesn't matter, they can make up for it later.

Don has a new aspiration now, and they have all the time in the world.

chrono - previous - next

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Feathers of all kinds are abundantly produced by Uanlikri's fauna and abundantly used in adornments all over the continent. Good feathers (bright colours, durable, a practical size), however, are less common. South of the Kantishian mountains, however, feathers too small don't stop antioles from hunting small and colourful birds: some peoples, like the Xigdat, are well known for extremely delicate featherwork, but also for their bird taxidermy, turning whole birds into decorative tassels where the bird's full pattern and array of colours can be admired.

These two species of birds, though they look much like Earth's modern passerine birds, are actually enantiornithes and do not have beaks. Instead, they have delicate jaws filled with tiny teeth. Both these species are generalist insectivores, and very sought after for use as adornments.

Both these birds have been featured as adornments on Xigdat dress: closeups under the cut.

#art by me#'tober#worldbuilding#uanlikri#antiole world#fauna#birds#speculative evolution#speculative biology#antiole fashion#it's gonna be birds for the next few days. might be birds till the end of the month actually for a certain value of bird.#more on that tomorrow

67 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello, i have a suggestion for your church vestments series!

Mexican featherwork was sometimes given to colonial powers in the Renaissance and there's a famous mitre:

https://www.liturgicalartsjournal.com/2024/06/the-fifteenth-century-mitre-made-by.html?m=1

ooh, cool, thanks!

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The discovery, made by Dr. Ruth Shady Solís and her team from the Caral Archaeological Zone (ZAC) of Peru’s Ministry of Culture, offers a glimpse into the prominent role of women in early Andean society."

by Dario Radley April 25, 2025

Archaeologists in Peru have unearthed a well-preserved 5,000-year-old burial of a high-status woman at the Áspero archaeological site—an ancient fishing settlement associated with the Caral civilization, the oldest civilization in the Americas. The discovery, made by Dr. Ruth Shady Solís and her team from the Caral Archaeological Zone (ZAC) of Peru’s Ministry of Culture, offers a glimpse into the prominent role of women in early Andean society.

Remains of a 5000-year-old woman from the Caral civilization. Credit: Ministry of Culture of Peru (Ministerio de Cultura del Perú), via www.gob.pe. Used for non-commercial news coverage purposes.

The burial was unearthed at Huaca de los Ídolos, a public ceremonial building in Áspero, a site on the Peruvian coast in the Barranca province, some 180 kilometers north of Lima. Áspero was one of the principal satellite cities of Caral, a UNESCO World Heritage site, and flourished from 3000 to 1800 BC—contemporaneous with ancient Egypt, Sumer, and China, though it developed in complete isolation.

The remains are those of a woman between the ages of 20 and 35 years old and about 1.5 meters (5 feet) tall. What is remarkable about this find is the state of preservation: archaeologists recovered parts of her skin, nails, and hair—a very uncommon condition for human remains in the region. She was wrapped in multiple layers of cotton fabric and rush mats and covered with an embroidered feather mantle of bright macaw feathers, an art form that is one of the oldest surviving examples of Andean featherwork.

With the body was a rich collection of funerary offerings carefully arranged in two tiers. These consisted of bottle-shaped vessels, reed baskets, a bone needle with intricate incisions, a shell that most likely came from the Amazon basin, weaving tools, a piece of woolen textile, a fishing net, a toucan beak inlaid with green and brown beads, and over thirty sweet potatoes. The items not only point to the high social standing of the woman but also to the advanced trade and cultural networks in which the Caral society was a part, stretching as far as the Amazon.

According to an official statement from the Peruvian State, the discovery of the feathered panel and other exquisitely worked objects “indicates a high level of development of specialized techniques during the Caral Civilization.” The feather artwork, in particular, indicates the symbolic and aesthetic sophistication achieved by this ancient Andean civilization.

Researchers point out that the burial not only attests to the presence of elite female figures in Caral but also aligns with other elite burials unearthed at Áspero over the past several years—such as the “Lady of the Four Tupus” in 2016 and the “Elite Man” in 2019—a pattern showing ceremonial burials among the elite class. The burial group has been compared with the subsequent elite burial practices of La Galgada in the Áncash region, supporting the hypothesis of a society that bestowed special status and power on women.

A multidisciplinary team is now analyzing the woman’s remains and the associated artifacts to further understand her health, diet, cause of death, and the sociocultural use of the objects that accompanied her in burial.

More information: Ministerio de Cultura de Perú

#Peru#Women in history#Archeology#Áspero#the Caral civilization#Dr. Ruth Shady Solís#Huaca de los Ídolos#Archeological discoveries made by women

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Describe his fashion house; its costumers, designs, changes and history, etc.

QUESTIONS ABOUT CUNT FAGULA. accepting

so this is a post that's been on my to-do list from the start! this is a lot to get into, so i'm gonna break it up into parts, starting with:

PART I: HISTORY & DEVELOPMENT.

the start of the fashion house was very, very small. it was literally just lola, and he first started off hand-sewing until he had the money to spare on a sewing machine (a singer treadle machine). he learned to sew by apprenticing with a tailor, where he also learned some of the finer details of what goes into garment-making.

initially, he just made clothes for himself, but once he had his sewing machine, he started visiting the black-owned boutiques and selling some pieces through them. while new orleans was considerably more progressive in terms of racial equality than a lot of places, particularly in the south, racism was still very much present, and he didn't really want to even attempt to deal with the white-owned boutiques, even though there were more of them and they got more business, and he personally benefited from lightskinned privilege.

soon, he had a deal with one specific boutique, where he would sell his pieces through them, which continued for a while even after he had enough money for a space for his atelier (workshop). at this point, he began dealing more in couture (high-end custom pieces) and began hiring employees. he started with a single seamstress, which was enough, for a while, but between the two of them, only so much could get done in a day, so he brought on more seamstresses over time.

at a certain point, things just sort of took off. he eventually brought on another designer, and then another, usually those who he'd already employed as seamstresses. lola always had final say on every design, and that continues today, but he was able to engage in more business with more than just himself producing designs.

at the time when business was really taking off and lola had more money than he knew what to do with, he moved the atelier to a location where a boutique could be established at the front of the house, as well as provide more space for the atelier itself. the boutique serves a few purposes; pieces that were started but for whatever reason were never picked up by the client are sometimes sold here, but this is rare, considering the amount of money that goes into it (the lowest end would be daywear costing around $10,000, and the most he's ever charged for a single piece was a wedding dress that cost around $16,000,000, which doesn't include the accessories). seasonal collections are also sold here, and only a limited number of pieces are produced per design, keeping the brand highly exclusive and allowing him to charge exorbitant rates. clients are also seen in the boutique for fittings and alterations.

another development would be the type of items produced. initially, it was just clothing (shirts, blouses, dresses, pants, etc), but lola wanted to branch out into everything. over time, they began creating shoes, handbags, and jewelry -- the jewelry, i should mention, is only created to pair with custom pieces. the same techniques and artisans are used to make any metalwork that is worked directly into certain pieces (which lola himself is personally very prone to including in his own designs).

lola began to favor immortals for his artisans, since their skills could be honed far past that of any mortal, and he would never have to replace them, so there are several vampires working for the house, among others, doing the most complicated work, such as embroidery, featherwork, and metalwork. it should be noted that they're not the only ones doing this work, but they oversee everything in their respective wheelhouses.

while still human, lourdes had been making plans to move the atelier to paris and beginning the process of becoming a haute couture house (haute couture is regulated by the french government and has highly specific requirements). however, considering the small pool of haute couture houses and the heavy regulations, he felt it would be unwise to put himself under such scrutiny once he became a vampire, which is perhaps the only thing he laments in that regard, as haute couture is essentially the highest level of prestige for a fashion house. still, his brand is held in extremely high regard, particularly for the exclusivity and unique ornate designs.

#lore.🥀#when i tell u i've learned so much about high fashion.........#i've always been interested in fashion#but i didn't know about the intricacies of couture before considering making it lola's profession a few years ago

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

What's up. I made a GODOT GAME. For a GAME JAM.

It's a nonlinear puzzle platformer about a bunch of draconic minions making a giant statue! I didn't think I'd be able to make a game in 96 hours, let alone in an engine I've only really been using for a few months. But with the help of my friends and a bit of determination... here it is.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Creative Art with Photoshop.

0 notes

Text

Four-Cornered Hat

Wari

7th–9th century

Four-cornered hats, although found in burial sites as funerary offerings, have also been discovered with signs of repeated and general use, such as worn edges, ancient mends, and stains of hair oil. In Wari and Tiwanaku societies, four-cornered hats were likely worn by high-ranking men as symbols of power and status, both in life and in death. Figures wearing four-cornered hats are frequently depicted on ceramics from both cultures, worn alongside other elite regalia including elaborate textiles, featherworks, and beaded collars.

source

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Phantom’s Black Swan Ch.6

Ch.1 Ch.2 Ch.3 Ch.4 Ch.5

The air in the grand ballroom thrummed with a chaotic energy, a kaleidoscope of vibrant silks, glittering jewels, and masked faces. The annual masquerade ball was in full swing, a brief respite from the anxieties and artistic tensions that usually permeated the air. For Delphine, however, the prospect of attending had initially held little appeal. Social gatherings were not her forte, and the thought of forced gaiety felt particularly jarring after the unsettling encounter in the Phantom’s lair and the subsequent quiet defiance of her solitary practice.

It was Madame Giry, surprisingly, who had subtly encouraged her to attend. "A breath of air, Mademoiselle Laurent. Even the most dedicated artist needs to step away from the barre now and then. And besides," she’d added, her gaze knowing, "one never knows what one might observe in a crowd."

The decision to go was solidified by a chance encounter with one of the older costume makers. He’d found Delphine’s meticulously crafted Black Swan bodice tucked away in a storage chest. "Such a waste, Mademoiselle," he’d grumbled, his wrinkled hands stroking the rich black velvet, shining beads, and intricate featherwork. "A masterpiece gathering dust. Wear it tonight. Show them what might have been."

And so, Delphine found herself amidst the swirling throng, a simple black velvet mask concealing the upper half of her face. The Black Swan bodice—worn with a large black Juliet tutu that she had used for some previous dances—repurposed with a few subtle alterations to make it suitable for the ball – the sharpest edges softened, the dramatic headdress replaced by a cascade of black feathers woven into her hair – felt both familiar and strangely poignant. It was a reminder of lost opportunity, but also a symbol of her enduring dedication.

Then she saw Christine. Across the crowded floor, bathed in a soft, almost ethereal light, Christine stood with Raoul. Her gown was a vision in white, adorned with delicate feathers that seemed to float around her like a halo. The resemblance to the White Swan was uncanny, an accidental mirroring that made Delphine’s stomach clench with a sudden, inexplicable embarrassment.

It was an accidental coincidence, she knew. Christine, now the reigning star, would naturally gravitate towards such a visually arresting and thematically resonant costume. Probably finding it reminiscent of the angels she had heard the girl talking about occasionally. The unintentional mirroring was… embarrassing. Delphine hadn’t sought attention, hadn’t considered the visual parallel. Most of the costumes at the yearly masquerade were jewel toned or shades of gold and silver. Now, amidst the sea of colorful costumes, they stood out – a stark contrast of black and white, shadow and light. It felt almost deliberate, a silent commentary she hadn’t intended to make.

She kept to the edges of the ballroom, observing the spectacle. Getting out was well-needed, but the compromise she had to make with dealing with the unintended embarrassment and conversation wasn’t something she’d prepared for. The music swelled and dipped, couples twirled across the polished floor, the masked figures, the forced laughter, the fleeting connections. Delphine watched, a detached observer, her mind still preoccupied with the enigmatic figure in the opera’s depths and the unsettling shift in the atmosphere surrounding Christine. The prima donna, for all her outward joy, sometimes carried a fleeting shadow in her eyes, a hint of unease that belied her radiant smile.

Raoul, however, seemed utterly besotted, his gaze never straying far from Christine. His presence seemed to bring a light to her eyes. Their happiness was a tangible thing, a bright flame in the dimly lit corners of the ballroom. She saw the opera management attempting a semblance of normalcy, their smiles strained. And she couldn’t shake the feeling that beneath the glittering façade, the Phantom’s presence lingered, an unseen shadow cast over the festivities. Like a purposeful ignorance for the sake of maintaining some facade of normalcy and peace, the calm before the storm, relatively speaking.

As the evening wore on, the revelry reached its peak. The orchestra played a frenzied waltz, the dancers a blur of motion. Suddenly, a hush fell over the ballroom. The music stuttered and died. A collective gasp rippled through the crowd as a new figure appeared at the grand staircase.

He stood on the staircase, framed by the flickering torchlight, a terrifying vision in crimson. Dressed as the Red Death from Edgar Allan Poe’s macabre tale, his flowing robes were the color of dried blood, his tall, skeletal mask a chilling visage of mortality. The air around him seemed to crackle with an unseen energy, a palpable sense of dread that silenced the boisterous celebration.

Delphine felt a cold dread grip her. There was something undeniably familiar in the figure’s bearing, in the way he moved with a silent, predatory grace. Her breath hitched in her throat. It couldn’t be… could it?

Christine gasped, her hand flying to her mouth, her eyes wide with terror. Raoul instinctively stepped in front of her, his face hardening with protective fury.

The Red Death descended the stairs slowly, his unseen gaze sweeping across the petrified crowd. He moved with a singular purpose, his attention seemingly fixed on Christine. The joyous masquerade had been shattered, replaced by a chilling tableau of fear and foreboding. The crowd of masked faces parted, squishing into the corners of the ballroom. Delphine, hidden amongst the shadows in her black swan attire, felt a cold certainty settle in her heart. The Phantom had made his dramatic entrance.

The Red Death, a figure of chilling authority, allowed the silence to stretch, amplifying the terror that gripped the ballroom. His skeletal mask swiveled slowly, taking in the frozen faces of the opera's patrons and its bewildered staff. Then, his voice, amplified by the cavernous space, cut through the tension – deep, resonant, and utterly devoid of warmth.

"Good evening, dear patrons. Forgive my unscheduled appearance, but the spirit of this masquerade, much like the spirit of this opera house, has grown… complacent."

His gaze, unseen behind the mask, settled directly on the trembling figures of Monsieur Firmin and Monsieur André, the co-managers, who stood aghast near the edge of the crowd.

"I have a new opera," the Phantom declared, his voice gaining a chilling edge of command. "One that will truly awaken the dormant soul of this establishment. Don Juan Triumphant."

A nervous ripple went through the crowd. Murmurs of "Don Juan?" and "He wrote an opera?" spread like wildfire. Firmin, finding a sliver of courage, stepped forward, his voice a strained whisper. "Sir, this is hardly the time... this is a private event. And as for a new opera, we have our season planned—"

The Red Death moved, a swift, unnerving glide that brought him within an arm's length of the bewildered manager. "Your season is my season, Monsieur Firmin," he hissed, his voice dropping to a dangerous growl that seemed to vibrate through the very floorboards. "And Don Juan Triumphant will be performed. Immediately."

A collective gasp swept the ballroom as the Phantom extended a gloved hand, its long, bony fingers hovering inches from Firmin's face. The unspoken threat hung heavy in the air. Firmin, his face ashen, visibly paled and stammered. "But... but the cast! The rehearsals! It's impossible!"

"Nothing is impossible for me," the Phantom retorted, his voice rising, resonating with a terrifying power. "Christine Daáe will be the lead. And the rest of the company will follow my instructions, or they will face… severe consequences." His gaze swept over the petrified faces of the dancers and chorus members, a silent, chilling promise.

Delphine, still cloaked in the dark velvet of her Black Swan costume, watched from the periphery, a cold knot forming in her stomach. She knew this man. She had confronted him in his lair, stripped him of his ghostly mystique, and seen him as nothing more than a bitter, isolated individual. Yet, here he was, terrifying the entire company, wielding an undeniable power that belied his human form. Her earlier defiance in his lair, the stark accusation of "just a man," suddenly felt terribly small against this grand, terrifying display.

His attention remained fixed on Christine, who stood pale and trembling beside Raoul. The Phantom’s gaze lingered on her, a possessive intensity that cut through the space. Delphine saw it – the old obsession, still burning, still claiming its target. This whole masquerade, this dramatic interruption, was for Christine. Don Juan Triumphant, his own opera, designed for her voice.

The Phantom continued to issue his commands, his voice chillingly precise as he dictated terms to the terrified managers. He spoke of new arrangements, swift rehearsals, the very air seeming to vibrate with his absolute will. And through it all, Delphine noticed a subtle, almost imperceptible avoidance in his movements. As his gaze swept over the petrified faces, it would skim past her, never quite meeting her eyes, even as she stood in the shadows which cloaked her.

But he knew she was there, a stark silhouette in her black swan attire, a direct challenge to his authority from their last encounter. He didn't want to meet her eyes, not now. He needed to reassert his dominance, to solidify his control over his opera house, and her defiant presence was an inconvenient, unsettling reminder of a vulnerability he was not yet ready to acknowledge. He kept his attention focused on Christine, whose terrified eyes were fixed on him, a more predictable and satisfying reaction. He was Christine's "Angel," and she would obey. Yet, despite his efforts, his gaze kept snagging on a fleeting glimpse of black velvet, a cascade of dark feathers at the edge of his vision.

Delphine’s lip curled in a silent, bitter assessment. He was still upset. Her confrontation, her dismissal of his “help” and his authority, had clearly wounded his pride. He was pointedly ignoring her, perhaps as a silent punishment, or to assert his dominance in front of the very people she’d tried to defend. Ridiculous, she thought. He was still so petty, so consumed by his ego. He could terrorize an entire opera house, but he couldn't face the woman who had called him "just a man." The thought ignited a fresh spark of defiance within her. He might choose to ignore her, but she would not be dismissed.

The Phantom’s monologue continued, a chilling declaration of his absolute control over their lives, their art. He outlined the swift timeline for Don Juan, the impossibility of it, all dismissed with a wave of his gloved hand. Delphine watched Christine’s terror, Raoul’s protective stance, and the managers’ horrified submission. She felt the weight of the Phantom’s threat, the chilling implication that every member of the company was now under his thumb. Even her. And that frightened and angered her at the same time. It was pathetic. Infuriating. He was still trying to prove something, to cling to his fantastical facade of being a phantom, despite her seeing through it. The thought spurred a fresh wave of defiance. Very well. If he wanted to play this game, if he wanted to ignore her because she had challenged him, she would show him. She would show him that his blackmail meant nothing. She would work twice as hard, not for him, but to prove to herself, and to everyone else, that her talent stood on its own, untainted by his shadow. Let him avoid her gaze; she take this as her opportunity to prove him wrong and be the best damned person in his opera.

0 notes

Text

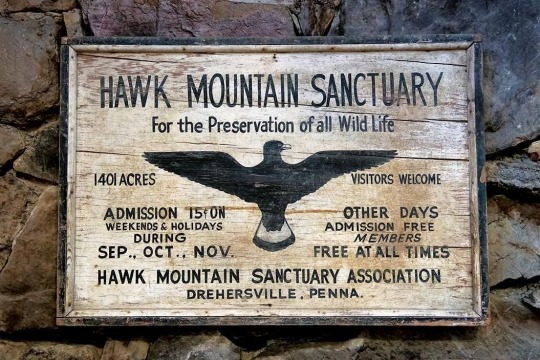

How Mrs. Edge Saved the Birds

Meet A Forgotten Hero of Our Natural World Whose Brave Campaign To Protect Birds Charted A New Course For The Environmental Movement

— Michelle Nijhuis | Photographs By Melissa Groo | Published: April 2021 | Wednesday May 21, 2025

One frosty October morning, I climbed a winding mile-long path to the North Lookout at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in Eastern Pennsylvania. Laurie Goodrich, the director of conservation science, was already on watch, staring down the ridge as a chilly wind swept in from the northwest. She has been scanning this horizon since 1984, and the view is as familiar to her as an old friend.

“Bird coming in, naked eye, slope of Five,” Goodrich said to her assistant, using a long-established nickname for a distant rise. A sharp-shinned hawk popped up from the valley below, racing by just above our heads. Another followed, then two more. A Cooper’s hawk swooped close, taking a swipe at the great horned-owl decoy perched on a wooden pole nearby. Goodrich seemed to be looking everywhere at once, calmly calling out numbers and species names as she greeted arriving visitors.

Like the hawks, the birdwatchers arrived alone or in pairs. Each found a spot in the rocks, placed thermoses and binoculars within easy reach, and settled in for the show, bundling up against the wind. By 10 a.m., more than two dozen birders were at the lookout, arrayed on the rocks like sports fans on bleachers. Suddenly they gasped—a peregrine falcon was barreling along the ridge toward the crowd.

By the end of the day, the lookout had been visited by several dozen birders and a flock of 60 chatty middle-schoolers. Goodrich and her two assistants—one from Switzerland, the other from the Republic of Georgia—had counted two red-shouldered hawks, four harriers, five peregrine falcons, eight kestrels, eight black vultures, ten merlins, 13 turkey vultures, 34 red-tailed hawks, 23 Cooper’s hawks, 39 bald eagles and 186 sharp-shinned hawks. It was a good day, but then again, she said, most days are.

In the early 1930s, Edge saw this picture of raptors shot by hunters on Hawk Mountain. The carnage so appalled her she bought the property to create a bird sanctuary. Courtesy of Hawk Mountain Sanctuary

The abundance of raptors at North Lookout owes a great deal to topography and wind currents, both of which funnel birds toward the ridgeline. But it owes even more to an extraordinary activist named Rosalie Edge, a wealthy Manhattan suffragist who founded Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in 1934. Hawk Mountain, believed to be the world’s first refuge for birds of prey, is a testament to Edge’s passion for birds—and to her enthusiasm for challenging the conservation establishment. In the words of her biographer, Dyana Furmansky, Edge was “a citizen-scientist and militant political agitator the likes of which the conservation movement had never seen.” She was described by a contemporary as “the only honest, unselfish, indomitable hellcat in the history of conservation.”

* * *

Throughout history, birds have been hunted not only for meat, but for beauty. Aztec artisans decorated royal headdresses, robes and tapestries with intricate featherwork designs, sourcing their materials from elaborate aviaries and far-flung trading networks. Europe’s first feather craze was kicked off by Marie Antoinette in 1775, when the young queen started to decorate her towering powdered wig with immense feather headdresses. By the late 19th century, ready-to-wear fashions and mail-order firms made feathered finery available to women of lesser means in both Europe and North America. Hats were decorated with not only individual feathers but the stuffed remains of entire birds, complete with beaks, feet and glass eyes. The extent of the craze was documented by the ornithologist Frank Chapman in 1886. Out of 700 hats whose trimmings he observed on the streets of New York City, 542 were decorated with feathers from 40 different bird species, including bluebirds, pileated woodpeckers, kingfishers and robins. Supplying the trade took an enormous toll on birds: In that same year, an estimated five million North American birds were killed to adorn ladies’ hats.

A carving of a northern harrier at the Hawk Mountain visitors center. This medium-sized raptor is sometimes called the “good hawk” because it doesn’t prey on poultry. Melissa Groo

Male conservationists on both sides of the Atlantic tended to blame the consumers—women. Other observers looked deeper, notably Virginia Woolf, who in a 1920 letter to the feminist periodical the Woman’s Leader spared no sympathy for “Lady So-and-So” and her desire for “a lemon-coloured egret...to complete her toilet,” but also pointed directly at the perpetrators: “The birds are killed by men, starved by men, and tortured by men—not vicariously, but with their own hands.”

In 1896, Harriet Hemenway, a wealthy Bostonian from a family of abolitionists, hosted a series of strategic tea parties along with her cousin Minna Hall, during which they persuaded women to boycott feathered fashions. The two women also enlisted businessmen and ornithologists to help revive the bird-protection movement named after wildlife artist John James Audubon, which had stalled shortly after its founding a decade earlier. The group’s wealth and influence sustained the Audubon movement through its second infancy.

In the late 19th century, hats like this one, in a French magazine, flaunted feathers or even stuffed birds—and took a toll on avian populations. Popperfoto / Getty Images

Hemenway and her allies successfully pushed for state laws restricting the feather trade, and they championed the federal Lacey Act, passed in 1900, which banned the interstate sale and transport of animals taken in violation of state laws. Activists celebrated in 1918 when Congress effectively ended the plume trade in the United States by passing the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Over the following years, bird populations recovered. In Florida in the 1920s, participants in the national Christmas bird count—an Audubon tradition inaugurated by Chapman in 1900—reported total numbers of great egrets in the single digits. By 1938, one birdwatcher in southwestern Florida counted more than 100 great egrets in a single day.

The end of the plume trade was an enormous conservation success, but over the next decade, as the conservation movement matured, its leaders became more complacent and less ambitious. On the brink of the Great Depression, Rosalie Edge would start to disturb their peace.

Edge was born in 1877 into a prominent Manhattan family that claimed Charles Dickens as a relation. As a child, she was given a silk bonnet wreathed with exquisitely preserved ruby-throated hummingbirds. But until her early 40s, she took little interest in living birds, instead championing the cause of women’s suffrage. In late 1917, New York became the first state in the eastern United States to guarantee women the right to vote, opening the door to the establishment of nationwide women’s suffrage in 1920. Edge then turned her attention to taming Parsonage Point, a four-acre property on Long Island Sound that her husband, Charlie, had purchased in 1915.

During World War I, with house construction delayed by shortages, Edge and her family lived on the property in tents. Every morning, she crept out to watch a family of kingfishers, and soon became acquainted with the local quail, kestrels, bluebirds and herons. While her children Peter and Margaret, then 6 and 4, planted pansies in the garden, Edge decorated the trees and shrubs with suet and scattered birdseed on the ground.

Edge (in an undated picture at Hawk Mountain) was not easily daunted by criticism. After an Audubon attorney called her a “common scold,” she scoffed, “Fancy how I trembled!” Courtesy of Hawk Mountain Sanctuary

In spite of their joint endeavors at Parsonage Point, Edge and her husband drifted apart. After an argument one evening in the spring of 1921, Rosalie left with the two children for her brownstone on the Upper East Side. The Edges did not divorce, but they eventually secured a legal separation, which both avoided the scandal of a public divorce and required Charlie to support Rosalie with a monthly allowance—which he reliably did. For Rosalie, however, the split was devastating. She mourned not only the loss of her husband, but the loss of her home at Parsonage Point—“the air, the sky, the gulls flying high.”

For more than a year, Edge took little notice of the birds around her. But in late 1922, she began to make notes on the species she saw in the city. Three years later, on a May evening, she was sitting by an open window when she noticed the staccato shriek of a nighthawk. Years later, she would muse that birdwatching “comes perhaps as a solace in sorrow and loneliness, or gives peace to some soul wracked with pain.”

A Hawk Mountain sign from the 1930s. Admission is now $10 for an adult day pass, or $50 for an annual membership. The sanctuary has since grown to encompass 2,600 acres. Melissa Groo

Edge began birding in nearby Central Park, often with her children and red chow chow in tow. She soon learned that the park was at least as rich in bird life as Parsonage Point, with some 200 species recorded there every year. At first, Edge’s noisy entourage and naive enthusiasm irritated the park’s rather shy and clannish community of bird enthusiasts. She was a quick learner, however, and she began checking the notes that Ludlow Griscom, then the American Museum of Natural History’s associate curator of birds, left for other birders in a hollow tree each morning. Soon, she befriended the man himself. Her son, Peter, shared her renewed passion for birdwatching, and, as she grew more knowledgeable, she would call his school during the day with instructions about what to look for during his walk home. (When the school refused to pass on any more phone messages, she sent a telegram.)

Edge gained the respect of park birders, and in the summer of 1929, one of them mailed her a pamphlet called “A Crisis in Conservation.” She received it at a Paris hotel where she was ending a European tour with her children. “Let us face facts now rather than annihilation of many of our native birds later,” the authors had written, arguing that bird protection organizations had been captured by gun and ammunition makers, and were failing to guard the bald eagle and other species that hunters targeted.

“I paced up and down, heedless that my family was waiting to go to dinner,” Edge later recalled. “For what to me were dinner and the boulevards of Paris when my mind was filled with the tragedy of beautiful birds, disappearing through the neglect and indifference of those who had at their disposal wealth beyond avarice with which these creatures might be saved?”

A wooden peregrine falcon at the visitors center. These birds are found all over the world—peregrinus is Latin for “traveler”—but climate change has altered their migrations. Melissa Groo

When Edge returned to Manhattan, her birding friends suggested she contact one of the authors, Willard Van Name, a zoologist at the American Museum of Natural History. When they met for a walk in Central Park, Edge was impressed by his knowledge of birds and his dedication to conservation. Van Name, who had grown up in a family of Yale scholars, was a lifelong bachelor and confirmed misanthrope, preferring the company of trees and birds to that of people. He confirmed the claims he had made in “A Crisis in Conservation,” and Edge, appalled, resolved to act.

* * *

On the morning of October 29, 1929, Edge walked across Central Park to the American Museum of Natural History, noting the birds she saw along the way. When she entered the small ground-floor room where the National Association of Audubon Societies was conducting its 25th annual meeting, the assembly stirred with curiosity. Edge was a life member of the association, but annual meetings tended to be familial gatherings of directors and employees.

Edge listened as a member of the board of directors finished a speech extolling the association, which represented more than a hundred local societies. It was the leading conservation organization in North America—if not the world—during a time of intense public interest in wildlife in general and birds in particular. Its directors were widely respected scientists and successful businessmen. As the board member concluded his remarks, he mentioned that the association had “dignifiedly stepped aside” from responding to “A Crisis in Conservation.”

Edge raised her hand and stood to speak. “What answer can a loyal member of the society make to this pamphlet?” she asked. “What are the answers?”

At the time, Edge was almost 52 years old. Slightly taller than average, with a stoop that she would later blame on hours of letter-writing, she favored black satin dresses and fashionably complicated (though never feathered) hats. She wore her graying hair in a simple knot at the back of her head. She was well-spoken, with a plummy, cultivated accent and a habit of drawing out phrases for emphasis. Her pale blue eyes took in her surroundings, and her characteristic attitude was one of imperious vigilance—as a New Yorker writer once put it, “somewhere between that of Queen Mary and a suspicious pointer.”

Edge’s questions were polite but piercing. Was the association tacitly supporting bounties on bald eagles in Alaska, as the pamphlet stated? Had it endorsed a bill that would have allowed wildlife refuges to be turned into public shooting grounds? Her inquiries, as she recalled years later, were met with leaden silence—and then, suddenly, outrage.

Frank Chapman, the museum’s bird curator and the founding editor of Bird-Lore, the Audubon association magazine, rose from the audience to furiously condemn the pamphlet, its authors and Edge’s impertinence. Several more Audubon directors and supporters stood to berate the pamphlet and its authors. Edge persevered through the clamor. “I fear I stood up very often,” she recalled with unconvincing remorse.

A turkey vulture swoops over the trees near Hawk Mountain’s North Lookout. Sometimes called a buzzard, it flies low, sniffing out carrion. Melissa Groo

When Edge finally stopped, association president T. Gilbert Pearson informed her that her questions had taken up the time allotted to the showing of a new moving picture, and that lunch was getting cold. Edge joined the meeting attendees for a photograph on the museum’s front steps, where she managed to pose among the directors.

By the end of the day, Edge and the Audubon directors—along with the rest of the country—would learn that stock values had fallen by billions of dollars, and families rich and poor were ruined. The day would soon be known as Black Tuesday.

As the country entered the Great Depression, and Pearson and the Audubon association showed no interest in reform, Edge joined forces with Van Name, and the two of them spent many evenings in the library of her brownstone. The prickly scientist became such a fixture in the household that he began to help her daughter, Margaret, with her algebra homework. Edge named their new partnership the Emergency Conservation Committee.

The committee’s colorfully written pamphlets placed blame and named names. Requests for additional copies poured in, and Edge and Van Name mailed them out by the hundreds. When the Audubon leaders denied Edge access to the association’s list of members, she took them to court and prevailed. In 1934, faced with a declining and restive membership, Pearson resigned. In 1940, the association renamed itself the National Audubon Society and distanced itself from supporters of predator control, instead embracing protection for all bird species, including birds of prey. “The National Audubon Society recovered its virginity,” longtime Emergency Conservation Committee member Irving Brant wryly recalled in his memoir. Today, while the nearly 500 local Audubon chapters coordinate with and receive financial support from the National Audubon Society, the chapters are legally independent organizations, and they retain a grassroots feistiness recalling that of Edge.

The Emergency Conservation Committee would last for 32 years, through the Great Depression, the Second World War, five presidential administrations and frequent quarrels between Edge and Van Name. (It was Van Name who referred to his collaborator as an “indominable hellcat.”) The committee published dozens of pamphlets and was instrumental in not only reforming the Audubon movement but establishing Olympic and Kings Canyon national parks and increasing public support for conservation in general. Brant, who later became a confidant of Harold Ickes, Franklin Roosevelt’s secretary of the interior, remembered that Ickes would occasionally say of a new initiative, “Won’t you ask Mrs. Edge to put out something on this?”

* * *

“What is this love of birds? What is it all about?” Edge once wrote. “Would that the psychologists might tell us.”

In 1933, Edge’s avian affections collided with a violent Pennsylvania tradition: On weekends, recreational hunters gathered on ridgetops to shoot thousands of birds of prey, for sport as well as to reduce what was believed to be rampant hawk predation on chickens and game birds. Edge was horrified by a photo showing more than 200 hawk carcasses from the area lined up on the forest floor. When she learned that the ridgetop and its surrounding land was for sale, she was determined to buy it.

In the summer of 1934, she signed a two-year lease on the property—Van Name loaned her the $500—reserving an option to purchase it for about $3,500, which she did after raising funds from supporters. Once again she clashed with the Audubon association, which had also wanted to buy the land.

Edge, contemplating her new real estate, knew that fences and signs would not be enough to stop the hunters; she would have to hire a warden. “It is a job that needs some courage,” she cautioned when she offered the position to a young Boston naturalist named Maurice Broun. Wardens charged with keeping plume hunters out of Audubon refuges faced frequent threats and harassment, and had been murdered by poachers in 1905. Though Broun was newly married, he was not dissuaded, and he and his wife, Irma, soon moved to Pennsylvania. At Edge’s suggestion, Broun began to make daily counts of the birds that passed over the mountain each fall. He usually counted hawks from North Lookout, a pile of sharp-edged granite on the rounded peak of Hawk Mountain.

Left: Until the end of her life, Edge was commonly seen carrying binoculars and wearing a favorite piece of jewelry—a silver dragonfly brooch. Courtesy of Hawk Mountain Sanctuary. Right: Laurie Goodrich is the sanctuary’s director of conservation science—a position endowed by the late Armenian philanthropist Sarkis Acopian. Melissa Groo

In 1940, even T. Gilbert Pearson—the Audubon president emeritus who had scolded Edge at the 1929 meeting—paid a visit. After passing time with the Brouns and noting the enthusiasm of visiting students, he wrote a letter to Edge. “I was impressed with the great usefulness of your undertaking,” he wrote. “You certainly are to be commended for carrying through to success this laudable dream of yours.” He enclosed a check for $2—the sanctuary membership fee at the time—and asked to be enrolled as a member.

* * *

Over the decades, Hawk Mountain and its raptor-migration data would assume a growing—if mostly unheralded—role in the conservation movement. Rachel Carson first visited Hawk Mountain in the fall of 1945. The raptors, she noted with delight, “came by like brown leaves drifting on the wind.” She was then 38 and serving as a writer and editor for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “Sometimes a lone bird rode the air currents,” she wrote, “sometimes several at a time, sweeping upward until they were only specks against the clouds or dropping down again toward the valley floor below us; sometimes a great burst of them milling and tossing, like the flurry of leaves when a sudden gust of wind shakes loose a new batch from the forest trees.”

Fifteen years later, when Carson was studying the effects of widespread pesticide usage, she sent a letter to the sanctuary caretaker: “I have seen you quoted at various times to the effect that you now see very few immature eagles in fall migration over Hawk Mountain. Would you be good enough to write me your comments on this, with any details and figures you think significant?”

Broun responded that between 1935 and 1939, the first four years of the daily bird counts at Hawk Mountain, some 40 percent of the bald eagles he observed were young birds. Two decades later, however, young birds made up just 20 percent of the total number of bald eagles recorded, and in 1957, he had counted only one young eagle for every 32 adults. Broun’s report would become a key piece of evidence in Carson’s legendary 1962 book Silent Spring, which exposed the environmental damage done by widespread use of the pesticide DDT.

In the years since Maurice Broun began his daily raptor count from North Lookout, Hawk Mountain has accumulated the longest and most complete record of raptor migration in the world. From these data, researchers know that golden eagles are more numerous along the flyway than they used to be, and that sharp-shinned hawks and red-tailed hawks are less frequent passersby. They also know that kestrels, the smallest falcons in North America, are in steep decline—for reasons that remain unclear, but researchers are launching a new study to identify the causes.

And Hawk Mountain is no longer the only window on raptor migration; there are some 200 active raptor count sites in North and South America, Europe and Asia, some founded by the international students who train at Hawk Mountain every year. Taken together, these lengthening data sets can reveal larger long-term patterns: While red-tailed hawks are less frequently seen at Hawk Mountain, for example, they are now more frequently reported at sites farther north, suggesting that the species is responding to warmer winters by changing its migration strategy. In November 2020, Hawk Mountain Sanctuary scientist J.F. Therrien contributed to a report showing that golden eagles are returning to their Arctic summering grounds progressively earlier in the year. While none of the raptors that frequent the sanctuary are currently endangered, it’s important to understand how these species are responding to climate change and other human-caused disruptions.

Hawk Mountain’s South Lookout, shown here at sunrise, is close to the entrance gate and offers a view of an ice age boulder field known as the River of Rocks. Melissa Groo

“The birds and animals must be protected,” Edge once wrote, “not merely because this species or another is interesting to some group of biologists, but because each is a link in a living chain that leads back to the mother of every living thing on land, the living soil.”

Edge didn’t live to see this expansion of Hawk Mountain’s influence. But by the end of her life, she was widely recognized as one of the most important figures in the American conservation movement. In late 1962, less than three weeks before her death, Edge attended one last Audubon gathering, showing up more or less unannounced at the annual meeting of the National Audubon Society in Corpus Christi, Texas. Edge was 85 and physically frail. With some trepidation, president Carl Bucheister invited his society’s former adversary to sit on the dais with him during the banquet. When Bucheister led her to her seat and announced her name, the audience—1,200 bird lovers strong—gave her a standing ovation.

#The Smithsonian Magazine#Mrs. Edge#Saved the Birds 🦢🦅 🐦⬛🦜🦉 🕊️🦩🪿#Natural World#Protection of Birds#Environmental Movement

0 notes

Text

Chanel ambassador Go Youn Jung visited Le19M: Get to Know the Maisons She Visited