#his Entire performance with that. Show. with the kier statue.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i truly hope tramell tillman gets his ass ate

#SHOWSTOPPING performance#LEGEND#when he turned and SPRINTED out of the room away from dylan#his dance w the marching band#his Entire performance with that. Show. with the kier statue.#this wax statue that's 5 inches taller than you were in real life. <- Jaw Dropped#severance#severance spoilers#loverboy wordz

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

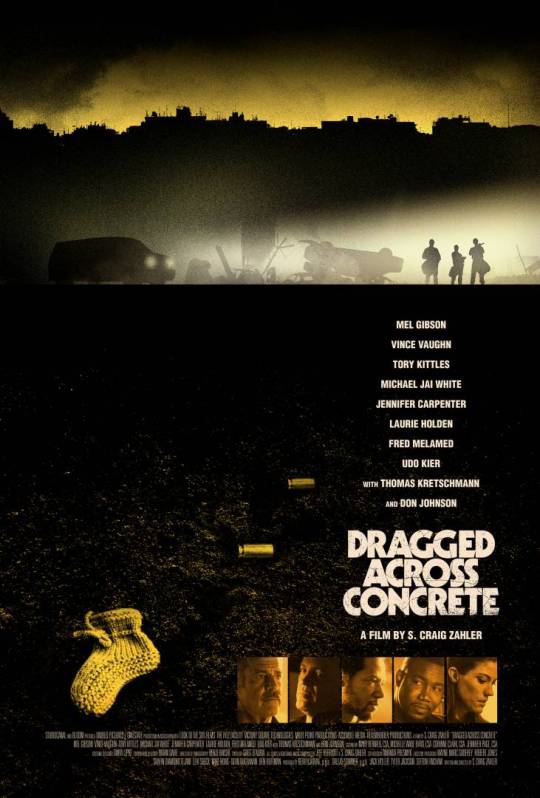

Dragged Across Concrete

When I sometimes attended my Film Studies classes at University one thing stuck with me from the Script Writing class; an economy of writing was critical to the success of your screenplay. It was a mantra echoing the sentiments of William Goldman’s “Arrive Late, Leave Early” approach to scene writing (as detailed in his books Adventures In The Screen Trade and Which Lie Did I Tell?). To his mind this prevents an audience getting “antsy”. It’s a notion S. Craig Zahler wholeheartedly disregards.

If Zahler’s first two films, Bone Tomahawk and Brawl In Cell Block 99, could be described as leisurely in pace (both clock in at 142min), then Dragged Across Concrete, with its hefty 159min, is positively lethargic (which, for context, is still only 10mins longer than the last Avengers movie and 5mins shorter than Blade Runner 2049), and will likely push most multiplex audiences to their limits. Holding it to The Goldman Standard; this could be the least economical screenplay ever filmed, but it’s all the better for it.

Going into this film you need to understand that you’ll have to bed down and submit to his tempo, which is at times almost static. Zahler builds scenes of great magnitude that draw his viewers in, enveloping them like a sphygmomanometer (I had to Google that), applying ever more pressure until it’s almost unbearable. Virtually scoreless throughout, there’s precious little to distract from Zahler’s writing, but thankfully he’s still one of the most refreshing wordsmith’s out there. He might not pack his dialogue with pop-culture references as Tarantino can do (someone he’s rather erroneously compared to), but his way with words is just as pleasing to the ear. It’s hard-nosed, pulpy writing that exists purely in a world of his creation - his actors chewing on his dialogue like a T-Bone. He can also show a man eat an entire sandwich in silence and have it pay off.

The most satisfying part of Zahler’s writing is that everything matters. There’s nothing throw-away about anything he shoots. The space he affords actors within the scenes allows them, and us, to take it all in without relying on cinematic shorthand to move things forward. No matter how long a scene is, it feels right, even (or especially) if that feeling is one of discomfort. The narrative drive of the film is relatively linear, we know exactly where we’re headed from early on, it’s in how Zahler stretches everything to breaking point in getting there that generates an anxiety that makes you shift in your seat; not the run-time. He can cut to the chase, but don’t be surprised if that chase is a leisurely tail across a freeway - the antithesis of Friedkin’s To Live & Die In L.A. but just as enthralling.

The other key attraction to a Zahler movie is his now notorious use of extreme violence. Whilst it would be disingenuous to say he has toned that down here (this is still far beyond much that you’ll see in your average movie these days), it is used more sparingly and dwelt upon less so than in his previous two. If Bone Tomahawk was sparse but unflinching in its depictions of depravity, and Brawl In Cell Block 99 relished the gonzo splatter effects of old, this time Zahler uses short, sharp jolts of violence to provoke the mind rather than overwhelm it. Often shots of explicit detail are cut away from so quickly that you’re still processing what you saw well into the next scene. It can have a disorientating effect, but one that makes you consider what you saw rather than simply have it thrown in your face.

Zahler also expands his eye for Old White Males, something I know many roll their eyes at, with his casting of Mel Gibson. Adding to the ranks of Kurt Russell and two time cast members Vince Vaughn, Don Johnson, Fred Melamed and Udo Kier, Gibson fits into Zahler’s aggressive, grim fatalism with ease. Some might consider this a role Gibson’s publicist might have urged him to avoid.

Since his original “cancellation”, Gibson has sought refuge in B-Picture pulp (Get The Gringo, Machete Kills, The Expendables 3) and couple of Father roles casting him as avenger/protector to wayward daughters (Edge Of Darkness, Blood Father) which all points to him acknowledging his new found villain status whilst also embracing a need for redemption (even the seeming outlier of Studio Festive Comedy Daddy’s Home 2 dines out on his asshole persona). Here though, the role of Brett Ridgeman felt too close to the bone for some; a bitter, mean son-of-a-bitch with a heavy-handed disdain for minorities. Be that as it may, Gibson is perfection and should be recognised for what is close to a career best - certainly it tops the list of performances in this second half of his career. Equal part hang-dog weariness and brittle rage barely concealed below a haggard surface, I can’t think of many others that could embody the character this wholly.

Gibson and Vaughn’s Anthony Lurasetti are police officers who find themselves suspended without pay for Ridgeman’s abusive arrest of a Hispanic drug dealer; an act captured on a cell phone and spread throughout local media. The idea that Zahler frames their subsequent descent into “crime to make ends meet” as right-wing apologist rhetoric for the "forgotten majority" has made many uncomfortable, and I don’t doubt for a second that this is by Zahler’s design. Do I think he holds those beliefs? I wouldn’t know, but this film is not one for the Red Hat brigade if that’s what concerns people, but it does wave those common red flags without flinching (look to the “Black Panic” scene in which Gibson’s daughter is tormented by black youths on her way home, Gibson’s character bemoaning his lowly wage forcing them to live in such a “shit hole” with a young daughter and disabled wife).

As counter-point, the third main protagonist Henry Johns, played by a revelatory Tory Kittles, offers another staple of the genre; the recently paroled felon in desperate need of cash (imagine Denis Haysbert’s role in Heat given more screen time) providing a cultural juxtaposition to the craggy old cop routine (he and his partner Biscuits even “whiting-up” at one point). Whilst he rises a notch or two above the others in the morality stakes, he’s no Magical Negro; his purpose is not to elevate or educate his white co-stars, he has as much stakes in the game as either (sharing a financial need for care-giving with Ridgeman), and just as much blood on his hands (and sometimes more...).

The Heat nod was clearly intentional, as Zahler cited that as a reference point in his Q&A, along with Dog Day Afternoon and Point Blank. Lofty comparisons they may be, but as a homage to those films, Dragged Across Concrete holds its own, albeit through the filter of a filmmaker that clearly loves exploitation cinema as much as any. Swimming in those waters, Zahler toes a fine line as to what audiences will find acceptable in both content and execution, and I think he’s pushed back against that line a little further here than he has before. It’s a provocative film without being insolently button-pushing and I’m sure it’s one that will divide audiences for some time (all but guaranteed to be a future Cult Favourite though).

There’s a scene that precedes the pivotal bank robbery that proved contentious to some during the screening I was at. We’re introduced to a character (one of the principle cast members) who we assume will form a large part in the film going forward, only for her screen time to be short lived and inconsequential to the plot. It makes for a quite harrowing and frustrating vignette, prompting one audience member to ask Zahler to account for its inclusion, a question met with spattered murmurs of approval around the auditorium. Zahler, clearly relishing the fact that this scene had struck a nerve, went on to explain (accurately) how everything from that point is framed in an entirely different way. It may have elicited anger from some of those watching, but he’s right in how that scene causes a shift in how you view the film and the protagonists going forward. He also acknowledged that, had he made this film under the watchful eye of a Studio and without his Final Cut deal, that scene would be the first thing any Producer would make him cut.

In a world dominated by audience pandering franchises, I think Zahler’s singular voice is one that needs to be preserved in tact, no matter how acquired a taste it may be.

2 notes

·

View notes