#jerusalemny

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Explosion of a ship, implosion of a life

By Jonathan Monfiletto

Marine Corps Sgt. Maj. William Anthony wasn’t born in Yates County, and he isn’t buried here either. It seems the only time he set foot on Yates County soil was for a month-long stint picking grapes in Jerusalem in the fall of 1899; his wife was from Guyanoga, and his son settled in the Dresden area as an adult. Otherwise, Sgt. Anthony had no connections here.

However, the memory of Sgt. Maj. Anthony and the story of his heroic deed continue to live on in Yates County – whether modern-day residents realize it – in the name of a road bearing his surname. Anthony Road, which runs from Route 14 southward into the village of Dresden, honors the man who played the role of a tragic hero in the story of the Spanish American War.

While recent findings suggest the explosion aboard the USS Maine was caused by a spontaneous fire in the coal bunker, in 1898 fingers pointed toward the ship being blown up by a mine set by Spanish forces. What isn’t under dispute is, first, that the incident led directly to the Spanish American War and, second, that it was then-Pvt. Bill Anthony who sounded the alarm to the ship’s commander about the explosion.

According to an article in the Penn Yan Democrat of February 17, 1933, Anthony was acting as orderly to Navy Cpt. Charles Sigsbee, the Maine’s commander, on February 15, 1898. The ship was anchored in the harbor of Havana, Cuba, “and all was peaceful when the deafening, rending blast rocked the vessel,” the newspaper stated, at approximately 9:40 p.m. Eastern time.

According to historian John Creamer, it was an oppressively warm and humid evening. The Maine had been sent to Cuba on a goodwill visit to protect American citizens and interests on the island nation, while tensions between the United States and Spain – which controlled Cuba at the time – reached a boiling point after building up for years. The Maine’s presence was meant to encourage Americans and Cubans and challenge the Spanish.

Creamer described Anthony’s experience that evening this way: “Private Bill took a long stroll on deck to postpone retiring to his steaming hammock below. There was no air conditioning then – in fact, the Maine was the first US Navy vessel to have electric lights. It was just as well for Bill that he dawdled, for at exactly 9:40 p.m. he and a number of others, on board the Maine and elsewhere around the harbor, saw a sheet of orange flame envelop the bow of the battleship. The explosion that followed was so tremendous that an eyewitness on another ship said that the Maine was lifted nearly out of the water by its force. … In the aftermath of the explosion, Private Bill realized that he had to get a message to Captain Sigsbee. He ran to the captain’s cabin in the dark. … The captain, not unaware that something had happened to the ship (he said later that he thought they were being fired upon by nearby Spanish guns), emerged from his cabin just as Private Bill arrived. In the darkness, the two men collided. … Private Bill backed off, apologized, saluted, and spoke the words that would put him into the history books.”

Those words, according to the Democrat, were: “I have the honor, sir, to report the Maine has been blown up and is sinking.” Sigsbee commended Anthony’s action in the captain’s record of the event, as transcribed in the Democrat: “The special feature in the case of this service performed by Private Anthony is that on an occasion when man’s instinct would lead him to seek safety outside the ship, he started into the superstructure and toward the cabin, irrespective of the danger. The action was a noble one and I feel it an honor to call his conduct to the attention of the recommendator that he be made a sergeant.”

Indeed, Anthony was promoted to sergeant and then, rather quickly, to sergeant major. According to Creamer, Anthony – 44 years old at the time – had served in the Marine Corps for 28 years. It is unclear what he did in the military prior to February 1898 – his service predates the Civil War – and why he remained a private for 28 years. Creamer notes promotions came slowly in those days – but apparently rapidly in the face of heroic acts – and there wasn’t much opportunity for a private to distinguish himself.

The disaster aboard the Maine killed 260 of the 328 crew members; indeed, only 16 were left uninjured. Though Anthony was listed among these 16, he received splinters in his face and through his hand when a lifeboat disintegrated in the explosion. He managed to climb into one of the remaining boats and row about the ship – in a hail of shrapnel and exploding ammunition – to look for survivors.

With no ship to serve on, Anthony subsequently was transferred to guard duty at the Brooklyn Navy Yard and given the highest enlisted rank in the Marine Corps. Anthony retired from the Marine Corps shortly after, in June 1898. Entitled to retirement pay after nearly 30 years of military service, Anthony – out of what the Democrat described as “character modesty” and fear “that the application might reflect on his superior officer who had helped him to get his rapid promotion,” Anthony declined the benefit and left the Marine Corps with no job and nothing but his name and reputation as a national hero.

Someone was looking to cash in on Anthony’s 15 minutes of fame, however, and a group of promoters convinced the Marine to take part in a play about the recently concluded Spanish American War, titled “The Red, White, and Blue.” Anthony’s role consisted of his appearing on stage in his Marine Corps uniform and reciting, “Remember the Maine!” to thunderous applause from the audience. However, the production closed quickly, as people were not ready to view a reenactment of a war they had just witnessed.

So, Anthony was once again out of work. In the interim, he got married to Adella Blancet, of Guyanoga, in October 1898. Adella had written to the national hero to seek his autograph; though he had received many such letters, for some reason Adella’s letter stood out and he wrote back to her. They soon wed and then had a son, William Jr., born in July 1898.

Following the grape harvest in the fall of 1899, Anthony left Adella and William Jr. in Guyanoga and traveled back to New York City to try to find work. He wasn’t willing to pull strings with his reputation and mention his struggle, and he lacked marketable skills outside of his military service.

On November 24, 1899, Anthony was sitting on a bench in Central Park when two police officers noticed him acting strangely with agitated behavior but also recognized who he was. Suddenly, Anthony pulled a small glass bottle out of his pocket and swallowed the contents. The officers attempted to help him, but he told them he didn’t want to be saved. Sure enough, Anthony died within an hour from an overdose of cocaine extract.

While the national hero was mourned following his shocking death, his name and reputation were quickly forgotten. Adella stayed in Yates County, and William Jr. grew up there. The son of the national hero married, became a successful farmer and vineyardist, served as Torrey town supervisor, and lived on the road that bears his family name.

In December 1942, the Navy remembered Anthony by launching the USS Anthony, a destroyer named in honor of the hero from the Maine. William Jr.’s daughters – Alice, a freshman at Keuka College, and Frances, a student at Penn Yan Academy – christened the ship bearing their grandfather’s name. In World War II, the destroyer saw action against the Japanese in the Philippines.

Interestingly, while William Jr. is buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Dresden – not too far from where Anthony Road enters the village – Anthony is buried in The Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn. Yates County continues to remember this non-resident who became a national hero.

#historyblog#history#museum#archives#american history#us history#local history#newyork#yatescounty#torreyny#dresdenny#jerusalemny#guyanogany#spain#cuba#ussmaine#spanishamericanwar#ussanthony#destroyer#ship

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

5 acres Recreational Land and Building Lot in Jerusalem NY. Located in the heart of the Finger Lakes near Keuka Lake and Canandaigua Lake. Build your seasonal cabin, year-round residence, or just enjoy this recreational property. Two existing campers will convey with the property. Italy Hill State Forest is located within minutes of the property and offers 1,899 acres of land for hiking, hunting, camping, and trapping. $29,999. Contact Ashley Hink 607-368-4029 or Keith Egresi 607-329-5172 for more information. @nylandquest #recreational #buildinglot #secluded #campers #camping #jerusalemny #yatescountyny #fingerlakes #keukalake #canandaigualake https://www.instagram.com/p/Cm2TeLgO5gw/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#recreational#buildinglot#secluded#campers#camping#jerusalemny#yatescountyny#fingerlakes#keukalake#canandaigualake

0 notes

Text

Are we there yet?

By C.J. Hartman Thompson

(The following article originally appeared in Bluff & Vine, a literary review featuring work created in and around the Finger Lakes region of New York State, and is published here with the permission of the magazine. This article also appeared in three parts in Yates Past, the bi-monthly newsletter of the Yates County History Center).

I vividly recall growing up in the 1960s and ’70s, as if it were yesterday. Two of my younger siblings, our parents, and me, sitting upon red padded chairs, separated as if by seniority around the outskirts of our chrome-legged Formica top table. There, as with most nights before, we conversed over our day’s events, with my mother monitoring our consumption, occasionally reminding us three kids, “Children in China would be grateful to have half the food we had on our plates!” This, a likely response to me chasing nasty whole beets about on my plate with a fork, while my sister pretended she liked the venison steak that she would eventually conceal in her napkin and later place in the trash. My brother, forever innocent, and the youngest at the time, would proclaim that my sister and I were staring at him, knowing full well that it would get us in trouble again.

We were all expected to clean our plates and leave the kitchen spotless or forfeit going for our nightly ride out on Bluff Point. Exiting our home toward the driveway, as if in response to the slam of our screen door, I recall yelling, “I have the middle,” as we piled into our 1972 green Pontiac Catalina in reckless abandon, absent of all regard for the use of seatbelts. None of us wanted to sit behind our father, because when he smoked his pipe, he would periodically empty it against his outside driver’s door handle, sending the ashes back into the rear window. Adorned with his corn-cob pipe, our father preferred a tobacco named Sir Walter Raleigh, which came in a variety of red and black tins. Back then, there wasn’t any consideration given to children purchasing tobacco products, and so I remember biking to either Loblaws or Charles Bollen’s Super Duper to purchase tobacco, filters, or pipe cleaners for Dad. Our dad, having grown up on Pepper Road, could tell you about every nook and cranny on Bluff Point there was to know. My siblings and I never knew where we would end up on these nightly adventures, as we called them.

We would leave our home on the lower West Lake Road, which was behind Race’s Willowhurst Garage. Our grandfather Alton owned and operated the garage after being discharged from the Army, having served in World War II. We would head south to Keuka Park, and on the lake side going toward Keuka Park, Dad and Mom told us that this larger red brick building in Brandy Bay was once the electric generating plant for the Penn Yan, Keuka Park and Branchport Railroad. One of our great-grandfathers, Ray Kenyon, had been a conductor on one of the trolley cars.

Brandy Bay had been the hot spot back in the day, as just behind the tracks, closer to the lake, there had been a place called Electric Park, where folks would spend summer evenings listening to music and dancing in a community pavilion. Our parents were quick to mention that the railroad and Electric Park were way before their time, certain that the passenger service had stopped in 1927, while the railroad continued to transport freight for some years afterward.

In the early ’60s, the lower West Lake Road ran directly from Indian Pines to the Brandy Bay trolley stop, passing scattered family-owned cottages along the way. Remnants of the original track lie east of today’s Central Avenue, which wouldn’t be constructed until many years later. Minutes from Brandy Bay, we would be at the stop sign with the main entrance of Keuka College on our left. Ball Hall, Hegeman Hall, and Harrington Hall looked very impressive to all of us. An all-female college at the time, Keuka College became co-ed in 1985. Both my sister and I agreed that we would attend there following our graduation from high school, and the college would later graduate five members of our immediate families.

Turning right after stopping, our parents, pointing left, acknowledged the location of a general store and café owned by the Johnson family close to where the former Keuka Park Fire Department building stands, now a storage facility for Keuka College. A gazebo has been constructed nearby, a gift from a Keuka College alumni. Further up the road on the right was the community center, which is now the location for the Branchport and Keuka Park Fire Department. By this point in the ride and yet only minutes from home, one of us kids would ask, “Are we there yet?” to which Dad likely replied, “Pipe down, sit back, and enjoy the ride.”

Once out of Keuka Park, we headed southwest up Skyline Drive, where we were encouraged to look for deer, be they in a field or hedgerow, coming to a stop the moment any of us saw one. I kid you not, it wasn’t out of the norm to spot herds in excess of 60 deer milling about the fields of the bluff near dusk. If the deer were standing close to the road, Dad, placing two fingers in his mouth, would send a loud whistle their way, scaring them back into the impenetrable woods. In truth, I think he enjoyed watching them hop and dart back to the safety of the trees, while telling us how the motion of their tails would signal to the other deer in the herd if danger were nearby. I laugh now as I could not tell you the number of times we would stop, each of us pondering, “Are we there yet?”

The Herrick Cemetery, an old cemetery associated with the Bluff Point community, is soon pointed out to us, as our fourth-great grandparents, Elisha and Charlotte “Latchie” Knickerbocker Kenyon are both buried there. The cemetery itself sits back maybe 50 yards from Skyline Drive and looks majestic, as it sits higher than the fields surrounding it. I have in recent years gone there and walked around. Numerous markers made from old limestone have either toppled over or are not even marked. Elisha and Charlotte’s markers looked to have been repaired. It is a beautiful and tranquil spot, as one can overlook the valley, the rolling hills, and surrounding vineyards. Now the trees, once saplings 60 years ago, are large deciduous trees with the exception of a lonesome pine, all offering shade to those who rest in peace beneath them.

This particular day had been a hot one, and thankfully it was slowly cooling down. The evening sun was hesitant to disappear, and from our vantage point it looked to be like a red orange balloon in the sky way off in the distance. We knew tomorrow would also be another sweltering day. The smell of Coppertone Sun-tan Lotion, applied earlier in the day, still lingered, having been outside all day. Still near the cemetery, Dad might then point out the Pinnacle, which is about the same elevation of 1,400 feet above sea level as Bluff Point. The Pinnacle is a peak that overlooks Bluff Point and Branchport.

The Esperanza Mansion, in the distance, was perfectly placed close to the tip of the Pinnacle and was completed in July of 1838 by John Nicholas Rose, a wealthy farmer from Virginia. Upon further research, the Roses for the most part had many of the early indigenous people known to inhabit Bluff Point along with a retinue of enslaved people provide much of the labor in construction of the mansion. It is believed that they transported the limestone from near the end of the Bluff by canoe to the shores currently in care of Keuka Lake State Park. The limestone provided necessary support in the construction of its 11- to 14-inch thick walls, complete with internal shutters to cover the windows, given the potential for rogue arrows to be directed at them.

Unbeknownst to me, the Esperanza Mansion was also part of the Underground Railroad during the Civil War. Mind you, as kids, Dad was simply pointing to a huge hill beyond the cemetery that had a huge house on it. We were impatient of course to get to wherever Dad was taking us. Even with all windows down, just sitting next to one another we were weary of the heat and our knees and elbows bumping into one another for what we thought had been a monumental amount of time. One of us again asked, “Are we there yet?” Mom turned around and gave us the look as if to say, you best not ask that again.

Further up the road from the cemetery, we take a right turn at the “V” intersection, remaining on Skyline Drive. Should one choose the road to the left, you are on Vine Road. At this junction stands a small house, formerly a two-room schoolhouse my father attended. With additional research, I found the original structure was built in 1860 for $395. Its location was known as Jerusalem District No. 4, Fingar District. Several improvements were made between 1861 and 1903; a coal stove replaced the wood-burning unit, walls were plastered, a wire fence was built, new student seats, an entrance hall was added, new floor installed, and shade trees were planted in 1903. The salary for one teacher for the winter and summer terms was $5 per week.

My siblings and I were astonished to think that the little house could be a school and that Dad had to walk to school with his siblings. Dad smirks when he tells us that he along with some of his buddies would tip over the outhouse when other students were in there. Though the distance seemed like miles to us, it was less than a half-mile from his Pepper Road home, absent concern for the weather. My siblings and I make eye contact across the large backseat, grateful to hop on a bus only minutes away from our home, transported to a larger school complete with running water and plumbing.

Still on Skyline Drive, we have now gone by the northwest entrance to Scott Road, as we still call it today. There is a house that looks to be half in the ground on the left. Mom mentions the property the house now resides upon was once left to my dad’s mother when her father had passed away, and for whatever reason, my grandparents relinquished their ownership, though the cost of additional taxes may have been motivation at the time.

If we were lucky, some nights we would see the occasional flock of turkeys trot across the road, as they like to roost just before sunset. Tempted by the possibility of an ice cream cone from Seneca Farms, we were all encouraged to increase our focus out the windows, in search of wildlife running amuck. We were rubbernecking, as competition grew to spot the next animal or feathered friend.

Just down the road a piece is the John Hall Road, which was and still is a dead end. The only things we could see from Skyline Drive were a huge barn and a house down over the hill surrounded by vineyards that looked as though they may well go all the way to the lake. Our ride proved to be more interesting and fun the further we went out on the bluff.

Arriving upon yet another old schoolhouse, which I have researched as being District No. 5, the Kenyon District, Scott Settlement District, Bluff Point District. This schoolhouse is located near the southern entrance of the Scott Road and Skyline Drive intersection. Today, the most recent owner of the schoolhouse has taken the roof off of the building and placed a huge telescope in its place, making it the perfect spot for an observatory.

Fewer houses embellish our views out of the Pontiac, as we make our way to the end of the bluff, soon approaching the home of Marland (Dutch) Griffith and his wife, Izzy (Isabelle Walrath) on the left.

They were both dear friends of our parents. I believe Dutch and Izzy owned around 210 acres out on the bluff, which had two houses and multiple outbuildings. One of the homes, not visible from the road, was in fact Dutch’s childhood home, complete with a working hand-pump above its dug well and a three-holed outhouse east of the dwelling. A large red barn to the south stored his wooden bobsleds and countless wooden beer lugs used to harvest grapes by hand, prior to modern convenience.

The house visible from Skyline Drive also had a pole barn where firewood, tractors, and implements were stored, while a wood framed hangar lay tucked away in the corner of a hardwoods, secreting Dutch’s single-engine plane, complete with canvas wings and but one seat.

An avid private pilot, Dutch was a member of the Penn Yan Flying Club, having earned his license by bicycling once a week to Penn Yan and back in his teens. Our mom, more curious than our father, once went for a brief ride in the plane. She recalls sitting upon a turned over 5-gallon bucket for a seat.

Before takeoff, Mom recalls asking Dutch if the door handle was secure enough. There was what looked to be a water hose going out onto the upper edge of the windshield from within the plane, transferring fuel to the engine. Dutch took Mom as far as Bath and back, she having a death grip on Dutch’s shoulder during the flight’s entirety. Liking the ride, she was no less happy to be back on the ground, and still the three of us begged to ask, "Are we there yet?”

The Scott family lived across from Dutch and Izzy, while the Disbrow family home and property lay to the south and east side of Skyline drive, separated by a vineyard retained by the Scotts. The Disbrow family still owns much of the land on both sides of Skyline Drive, running all the way to the Garrett property on the east side of Skyline Drive but ending somewhat sooner on the west side.

Mom excitedly tells us when Dad and she were first dating they walked down over the hill near Disbrows and carved their initials into a tree. The slanting rays of the setting sun gave the surrounding landscape a stunning panoramic view. We felt as though we were on top of the world. One could see only the tops of other hills, Barrington to the east and Pulteney to the west. We could see deer everywhere in the fields on both sides of the road.

We pulled over on the east side near the little old stone spring house that still today feeds water to the Garrett Chapel. We all got out to stretch our legs and gazed in the direction of the Wagener Mansion, built by Abraham Wagener in 1833 on the southern tip of Bluff Point. Dad mentioned the stones used to build the foundation of the mansion were rumored to have come from the early indigenous ruins on Bluff Point. The mansion is not only intimidating by its size, but the grounds around the residence were well taken care of.

Dad was like an encyclopedia, full of information that he wanted to share with us. He then mentions our great-grandfather, Ray Kenyon, had been the manager of Paul Garrett’s vineyards for a time. Dad, along with his father and brother, all worked for the Garrett family, tending to their vineyards and fields, often using work horses to complete many tasks up and over the steep terrain, better suited to billy goats.

In writing this story, I interviewed my brother, who spent countless hours hunting with our dad on the bluff. I inquired as to whether I had forgotten any significant locations we may have heard tell of during the course of our rides, and he had several: Besides knowing the whereabouts of abandoned wells of grave importance to hunters, he mentioned places like the Hogpen, the Hole, and the Hairpin. The latter two, still visible on Google Earth, each name assigned to trails forged for farming or logging, all located on the west side of Skyline Drive.

Conversation momentarily turns to ice cream, and the debate ensues as to who wants what, with many, “I changed my minds,” in between. Both Dad and Mom settle on splitting a banana split. Returning North on Skyline Drive, Dad decided to take the first left going down Pepper Road.

I have found in old articles that Pepper Road had also been called Pepperville Road. The property immediately on the west side of the road had once belonged to the Pepper family. John William Pepper and Ruth Annie Kirk had immigrated from Leicestershire, England. They raised their family on Bluff Point. Dad went into great detail describing how the farm was huge, with a great big white farmhouse and a barn. He had never been in the house but was told by other Pepper family members that there had been a wood kitchen stove, and water needed for the kitchen was brought up by the pail from a pump down the hill in the gully. There was also an outhouse.

They owned several animals: cows, horses to pull the plow, rabbits, chickens, and pigs. Best known for their Concord grape vineyards, they also had assorted apple, cherry, and pear trees as well as black and red raspberries and strawberries. This property is now part of Keuka Lake State Park. Sadly, the Pepper home perished in a fire.

Our ride down Pepper Road continued, and we only had to cross over West Bluff Drive, which was perpendicular to Skyline Drive. This next property belonged to Herb Valentine; he owned around 114 acres, with his property adjoining the Gridley property. Both Pepper and Valentine properties went down the hill from Skyline Drive to Keuka Lake.

Dad and his father had been out hunting deer on a cold December morning when they heard cries for help coming from the Herb Valentine property. They found Herb lying on the ground near the wood pile. He had gone out to get wood for his stove the night before and fallen. Unable to get up, he had laid there overnight. Thankfully, Mr. Valentine didn’t suffer any great harm.

The Finger Lakes State Park, as it was known then, filed notice of acquisition and transfer of deeds, dated November of 1961 after the death of Herb Valentine. The Pepper and Valentine property totaled close to 500 acres.

I remember Dad parking the car at the top of West Bluff Drive in the winter, as the road was and still isn’t plowed in the winter. My parents, my siblings, and I would trudge through the snow part way down West Bluff Drive with our sleds in tow. We would be exhausted just going sledding down the hill two or three times.

#historyblog#history#museum#archives#yatescounty#american history#us history#local history#newyork#jerusalemny#bluffpointny#keukalake

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

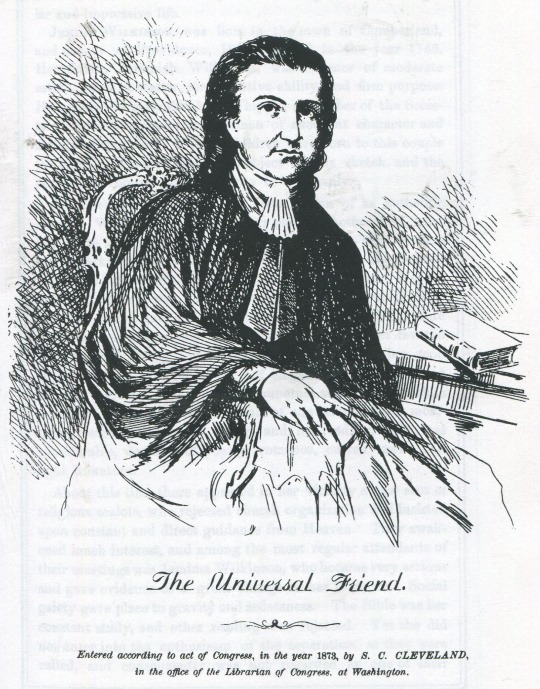

An insider's view of the Public Universal Friend

By Jonathan Monfiletto

A person identifying himself or herself only as “A Neighbor” and writing in the National Intelligencer newspaper, from Ontario County, New York on August 24, 1819, apparently had an insider’s view of the life of the Public Universal Friend and may have been present at the Friend’s death on July 1, 1819. Published from 1800 until 1870, the National Intelligencer was the first newspaper published in Washington, D.C., covering events around the nation’s capital and capturing news across the United States of America. On August 21, 1819 – according to A Neighbor, as I have been unable to find digitized editions of the Intelligencer – the newspaper ran the Penn Yan Herald’s July 6, 1819 obituary for the Friend. And, A Neighbor wrote to the newspaper (at the time, Ontario County encompassed the northern portion of what is now Yates County) to dispute some of the facts of the Herald’s obituary as printed in the Intelligencer.

Calling the Public Universal Friend by their birth name of Jemima Wilkinson, the Herald noted the Friend died “on Thursday last” of dropsy, nowadays known as congestive heart failure, at age 66. The Herald went on to describe what purportedly took place in the Friend’s final moments: “She, a few moments previous to her death, placed herself in her chappel [sic], and called in her disciples, one by one, and gave each a solemn admonition, then raised her hands and gave up the ghost. Thus the second wonder of the western country has made her final exit.” A Neighbor, however, contradicted this version of events.

First, in his or her response, a letter titled “Of the Late Jemima Wilkinson” and addressed to Messrs. Gales & Seaton, A Neighbor noted the Friend did not die in Penn Yan but in Jerusalem, 12 miles from Penn Yan – according to A Neighbor – on the roads of the time. Using the Herald’s article, the Intelligencer may have used Penn Yan as a dateline on its article. From there, A Neighbor told a different story of the Friend’s illness and final moments: “She never had a chapel; I therefore conclude she did not exhort her disciples, one by one, in her chapel (emphasis in original) – but at her bed side, where she has for a year or more been confined most of the time by a most excruciating complaint; and where, on Saturday of each week, she collected the remnant of her followers, and exhorted them. Her complaint may have been a case of dropsy, but if so, it assumed very unusual symptoms.”

The Herald’s obituary stated, “Much curiosity has been excited since her departure. The roads leading to her mansion were for a few days after her death literally filled with crowds of people, who had been, or were going to see the Friend!” The Herald also noted the community had not yet learned whether the Friend would have a successor to lead their followers and whether the Society of Universal Friends would remain united without its head. The obituary described the Friend’s mansion – their third home in what is now Yates County, their second in the modern-day town of Jerusalem, and the only one still standing today – as “stands on a barren heath amidst the solitudes of the wilderness, at some distance from this settlement.”

A Neighbor differed on these statements as well: “Her mansion is on a hill – but not a barren heath – for the eye of man has rarely seen a more romantic and luxuriant prospect than is displayed from the Eastern front of this mansion. The roads leading to her dwelling are said to have been literally filled with crowds of people! This mighty concourse of people might possibly have amounted to 100 souls, including all her society and spectators, on the day that it was expected she would have been interred.”

A Neighbor claimed in his or her letter to have been a neighbor of the Friend for six years as well as a resident in the home of the Friend and the homes of their followers. In conversations with the Friend, A Neighbor attempted to understand their “peculiar tenets” and comprehend “a correct idea of her doctrines,” but this task was difficult because the Friend answered questions by quoting Bible verses and recounting their visions, “leaving me to draw inferences to suit myself.” A Neighbor concluded the Friend believed in millenarianism – a belief in the second coming of Jesus Christ to establish a thousand-year reign on Earth – and gathered a thousand followers into the wilderness of the New Jerusalem 25 years before. Similarly, to reports that the Friend professed to be the Messiah, A Neighbor asked questions of the Friend to discern the truth, only to receive responses of Bible verses and the Friend’s visions. Nevertheless, it seemed the Friend encouraged their followers to believe they acted upon the inspiration of Christ.

A Neighbor had first encountered the Society 18 years before; at that time, the Society was wealthy but since then had fallen out over disputes and litigation. “Many have deserted her; and a remnant only has remained with her to the last.” At one time, according to A Neighbor, the Friend had 3,000 or 4,000 followers – including men who left their wives and families and women and children who deserted their homes – settle with them in the New Jerusalem, “where it was believed all the elect were to gather together, under her protection and ministry, and the millennium to take place.”

The Intelligencer apparently responded to A Neighbor’s letter; since I haven’t been able to locate a digitized version of these Intelligencer editions, I haven’t been able to view either article published in this newspaper. A Neighbor responded to the Intelligencer’s response in the November 23, 1819 edition, noting the newspaper had responded to his or her first letter in the October 13, 1819 edition “with a critical review of my hasty communication of August last, copied from the Penn Yan Herald.” A Neighbor spent much of the second letter repeating and asserting his or her claims about the Friend that contradict the statements put forth by the Herald and the Intelligencer. This included describing the 14-square-foot room that served as the Friend’s chamber, in which they received visitors and followers during their ministry and at their death, but A Neighbor noted it was never called a chapel. Apparently challenged on the claim that the Friend had 3,000 to 4,000 followers, A Neighbor instead stated that was the total number of the Friend’s followers throughout New England and Pennsylvania, while the Society had 500 members in the New Jerusalem when A Neighbor became acquainted with it in 1795.

A Neighbor also both praised the Friend and criticized their detractors: “That a woman with hardly a common school education, in a country like the eastern and middle states, and among a people so generally well informed as the Yankees, and in the face of able ministers, should have been able to effect what she has evidently effected, is truly a wonder, and worthy of an investigation. A correct history of her life, ministry, and doctrines, could not fail to be highly interesting. Such an [sic] one I should be glad to see published by a competent hand. But the idle and malicious tales now going the rounds of our newspapers, are certainly unworthy of belief, as well as disgraceful to the presses which give them circulation.”

A Neighbor noted in the community there are “some among us who appear to believe that she was something more than human – the messenger of truth, divinely sent,” while others “paint her as a downright devil in petticoats – artful, abandoned, libidinous, and wicked.” A Neighbor believed both groups were wrong; A Neighbor believed the Friend themself was deceived and did believe themself to be inspired by Christ. “Her preaching was impressive, and calculated to produce a powerful effect on some minds. She inculcated good moral precepts, and was deeply read in Scripture, which seemed to be her ready and universal appeal on all questions addressed to her concerning religion,” A Neighbor wrote. “She was hospitable, social, and pleased to see strangers, and visitors were kindly received at her mansion, and treated with kindness, and freely discoursed with, if they demeaned themselves decently.”

A Neighbor closed this second letter by observing there were many people around New York State who had visited the Friend and been treated kindly by them and thus who knew the truth about who they were as a person versus the rumors and slander in the newspapers. A Neighbor also charged the Herald with “circulating such tales to her prejudice” and stated the newspaper should “feel a proper delicacy and forbearance on the subject.” Thus, A Neighbor provided an insider’s view of the life and times of the Public Universal Friend to the Penn Yan community and to an American audience.

#historyblog#history#museum#archives#american history#us history#local history#newyork#yatescounty#pennyan#jerusalemny#publicuniversalfriend#societyofuniversalfriends#nationalintelligencer

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The last survivor

By Jonathan Monfiletto

In March 1793, when Henry Barnes was 4 years old, he moved with his parents – Samuel Barnes and Abigail Dains, devoted followers of the Public Universal Friend – and two of his siblings from his birthplace in Connecticut to the Friend’s Settlement in the Genesee Country. Eighty-one years later, when Henry died at age 85 on June 7, 1874, he was the last living adherent of the Society of Universal Friends.

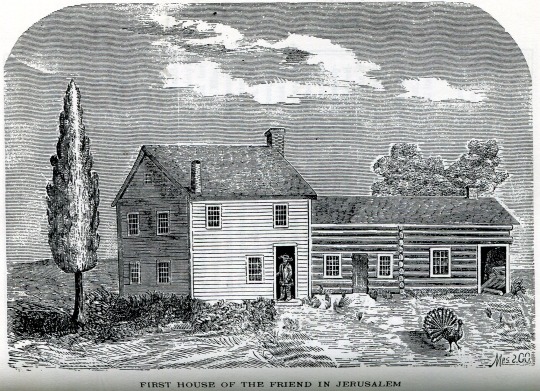

And Barnes wasn’t just the last survivor among the followers of the Friend, who became the first permanent, non-native settlers of what we now know as Yates County when they arrived in the late 1780s and early 1790s. Because of his longevity and memory, he was able to share his knowledge of the Friend and their Society to inform the people around him and record it for local history. Indeed, Stafford Cleveland – in his History and Directory of Yates County, published in 1873 – often cites Barnes as he relates the history of the Public Universal Friend and their followers. In the preface of his history, Cleveland calls Barnes “the most serviceable among living witnesses … who as a member of the Friend’s Society from his boyhood had an acquaintance with facts which it was important to understand fully and correctly.”

According to Cleveland, it was from Barnes’ memory that Cleveland’s wife, Obedience, drew illustrations for History and Directory of Yates County of the Society’s log meetinghouse in the Friend’s Settlement – about a mile inland of Seneca Lake in what is now the town of Torrey – and the Friend’s first home in the New Jerusalem, in the modern-day town of Jerusalem, a log home with a frame addition. Barnes apparently approved of both illustrations, calling them faithful reproductions.

In Cleveland’s history, Barnes’ name is included on a list of second-generation followers of the Friend – “the comparatively few of the second generation united with the Society” – and Cleveland notes the list of names contains only those who joined the Society of their own accord and who remained devoted throughout their lives. “Some of these never came to the New Jerusalem (when the Friend themself moved from Torrey to Jerusalem), but the most of them belonged to the pioneer families, and they were, as a body, people of the highest moral and personal worth,” Cleveland states. At the time Cleveland wrote, Barnes, Rachel Ingraham, and Experience Ingraham Barnes – Barnes’ sister-in-law – were the only living members of the Society; Rachel and Experience died that year.

Barnes was the youngest of five children – all sons – born to Samuel Barnes, a Connecticut farmer, and Abigail Dains, the sister of Jonathan, Castle, and Ephraim Dains, also followers of the Friend. Parmalee, the eldest son, followed the Society of Universal Friends to the New Jerusalem in 1789, and Elizur, the second son, came in 1791. Their parents and their three youngest brothers – Julius, Samuel, and Henry – traveled there in 1793. Though he was only 4 years old at the time, Barnes remembered the 16-day journey with a sleigh from Connecticut through Albany and the Mohawk Valley and then from Geneva to the Friend’s Settlement. Shortly after their arrival, his parents took him for a visit to the Friend’s home. “… and the attention bestowed upon him by that personage, made a vivid and lasting impression on his mind,” reads Barnes’ obituary in the Yates County Chronicle (the newspaper that Cleveland served as editor) of June 11, 1874. “No one was ever reared in more faithful compliance with the oracles of the Friend’s doctrine than was Henry Barnes. With the earnestness and credence of a child he imbibed it from his earliest years, and with the simplicity and integrity of a child he maintained it until the latest period of his life.”

Indeed, Abigail was included in Cleveland’s history on a list of women – similar to but apart from the Faithful Sisterhood, a group of women who abandoned their husbands and children to follow the Friend to the New Jerusalem – “who, as wives and mothers, and true exponents of the highest morality and social virtue, illustrated the pioneer life with examples worthy to be held in honored remembrance, and gave the Friend’s Society a name for virtue, industry and matronly worth, of which no pen can speak in adequate praise.” Cleveland called this group “a noble array of devoted women not of this select band (the Faithful Sisterhood),” and in a footnote he referred to Abigail as “a much beloved member of the Society.”

The Barnes family purchased land near Himrod from Charles Williamson and cleared 22 acres, remaining there until 1800 when they sold it and moved to Jerusalem. There, they cleared a little space within a dense wilderness and later moved to a homestead of 21 acres. Samuel died in 1809 at age 66, and Abigail died in 1842 at age 92. Barnes was “born and reared in the midst of the Friend’s Society,” according to Cleveland, and “has led a religious life in conformity to the doctrine and precepts of the Friend.” Barnes’ obituary states he was a member of the Friend’s household for many years, during “a considerable period of his minority … and also for several years thereafter,” regarding the Friend’s home as his home. In fact, the Friend’s mansion in Jerusalem, their third home, was Barnes’ home, “until the breaking up of the Society by the infusion of elements which seemed to him contradictory to the Friend’s teaching,” the obituary states.

In his early adulthood, Barnes worked as a farmer and a cooper, producing 1,600 flour barrels for Abraham Dox in 1814. Even though he completed a total of just 15 weeks of common school education – including 11 weeks under Dennis Dean, one of the earliest and best teachers of his time – Barnes began teaching school in 1823. He taught 30 terms of school in Jerusalem, Milo, Potter, Benton, and Italy, the last one in Italy at age 76. Barnes also served as Inspector of Schools in Jerusalem for 12 years and as Town Superintendent in Wheeler, Steuben County, where he lived for 12 years. Barnes is also included on a list of Overseers of Highways in 1819 in Cleveland’s history. He married for the first time at age 46 to Sarah Whitney, and when she died he married Elizabeth Mills, who died “several years ago,” Cleveland wrote. Barnes had no children of his own, dying at the home of his nephew-in-law and niece, Andrew and Rosetta Fingar, in the town of Benton in the present-day vicinity of Briggs Road and State Route 364.

Throughout Cleveland’s history, as well as supplying certain facts about the Public Universal Friend, Barnes provided some of his personal anecdotes to color the Friend’s story. For example, in helping draw the Friend’s first home in Jerusalem, Barnes recalled tapping in one day – using an axe and a gouge – 636 of the 2,000 maple trees within a half-mile-square space on the property. Followers of the Friend – both those who lived in their household and those who lived elsewhere, took care of the chores around the farm on the Friend’s property, and Barnes would accompany the Friend as they rode from field to field overseeing the operations. Once, in the spring of 1816, Barnes and Rachel Ingraham – “almost unassisted,” Cleveland noted – made more than 1,500 pounds of sugar in the Friend’s sugar camp.

In helping draw the Society’s meetinghouse in Torrey, Barnes told about the last service there in 1799. It was a warm summer day, according to Barnes, and a heavy thunderstorm arose, with rain pouring down and leaking through the roof. “Some of the women held a blanket or shawl over the Friend for protection, while she continued her discourse, which was one of the most impressive and eloquent of her life, and was listened to with profound attention by a large congregation, who crowded very compactly into the leaky structure,” Cleveland wrote. Barnes also remembered the white oak stump – hollowed out in the middle and used as a pestle to grind wheat and corn before the Society established a gristmill – that continued to stand near the Friend’s home in Torrey long after they left that area. Though Barnes didn’t help draw the Friend’s third home – referred to as their mansion – he did mention the tall fir trees he planted in front of the property.

There was also a section of Cleveland’s history titled “The Friend’s Doctrine as Stated by Henry Barnes.” Clearly, Barnes had both personal memories of the Public Universal Friend and institutional knowledge of the Society of Universal Friends.

#historyblog#history#museum#archives#american history#us history#local history#newyork#yatescounty#torreyny#jerusalemny#publicuniversalfriend#societyofuniversalfriends#henrybarnes

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Working for the children

By Jonathan Monfiletto

Susan Miller Dorsey already had nearly two decades of teaching experience under her belt when she began teaching Latin at the only high school in Los Angeles, California in 1896. Thirty-three years later, when she retired as superintendent of the Los Angeles school district, she had overseen the doubling of the student population of the fastest-growing school district in the world during the 1920s. At the time of her death in 1946, Dorsey had been the only living person to have a school in Los Angeles named after her.

Historian Rich MacAlpine captured Dorsey’s life in a nutshell for a March 2009 article in Yates Past, the bi-monthly newsletter of the Yates County History Center, that was reproduced in MacAlpine’s 2014 book Yates County Chronicles, so I won’t duplicate his efforts in this article. Just briefly, I will mention Susan Miller was born to James and Hannah Miller, of County House Road in Jerusalem, on February 16, 1857. She seems to have attended Jerusalem School District No. 17 in her childhood, and then she graduated from Penn Yan Academy at the age of 16 in 1873. After four years at Vassar College, she graduated in 1877 and embarked on a 20-year period of teaching in higher education as well as a career in social work. Marrying Patrick Dorsey – a fellow Yates County native – in 1881, Susan moved with her husband to California, where he was called as a pastor, shortly afterward.

From 1896 to 1902, Dorsey taught at Los Angeles High School and also served as the head of the school’s classical department. Her tenure with the Los Angeles school district follows a time in which her husband, taking their son, Paul, with him, decided to travel for better health and apparently abandon his wife in the process. However, Dorsey never described herself as divorced but did list herself as widowed upon Patrick’s death in 1927.

From 1902 to 1913, Dorsey presided as vice principal of the school, and then in 1913 she was selected assistant superintendent of the school district – the first woman to hold the position. She broke the glass ceiling yet again in 1920 when she was chosen to be the superintendent of the school district, despite her misgivings over the position and apparent desire not to hold it. While she is described as the first woman in the United States to be the superintendent of a metropolitan school system, a contemporary newspaper article lists her as the only woman in the country to hold such a position and notes this is a distinction for a former resident that Yates County should be proud of.

During her time at the helm of the Los Angeles school district, Dorsey accomplished several educational initiatives. According to newspaper accounts of her career, she established a visual education division, a classical center, an Americanization department, and three types of schools for practical and vocational preparation. She also enlarged the health and physical training sections and the elementary school library. She was an early advocate of the importance of kindergarten, and in her free time she volunteered in the city’s social welfare programs. This included working with the Chinese community and tending to those with tuberculosis as well as being a temperance advocate.

Her aim was to “solve vocational problems and train character,” she said, and she oversaw a school district whose area measured 965 square miles, with 400 schools and a $30 million budget ($544 million in today’s money) by the time she retired. In her near-decade as superintendent, the population of Los Angeles increased from 500,000 to 1.2 million while the student population increased from 135,000 to 350,000. School facilities tripled in size during that time as well.

In fact, having witnessed the present and foreseeing the future, Dorsey urged upon the importance of spacious grounds to allow room for future growth. “It is through her foresight and vision that school sites range from five to thirty acres, as she always has insisted that Los Angeles must look to future expansion and that the children of its citizens must build strong bodies on its school playfields,” one newspaper article stated.

Dorsey used her position to advocate for the modernization and advancement of education as the world modernized and advanced, noting in a speech “that young people be trained to become useful members of society should be the most important phase of education,” according to a newspaper article. The article captured the message of Dorsey’s speech this way: “The education that answered for the child of forty years ago when the world lived without telephones, automobiles, submarines, amplifiers, and the many electrical devices at command, will not fit the child to live in the world today.”

She also led a teacher-citizen committee that planned a convention to give parents the opportunity to hear from the greatest experts in child training in the country. “The movement to educate parents better to enable them in the upbringing of their children is state-wide,” one newspaper reported, stating an analysis of high school students “shows that some of the problems are lack of knowledge by parents, lack of supervision of the child’s leisure time, lack of acquaintance by parents with the companions of the child, lack of sympathetic cooperation with the child’s friends, lack of understanding, broken homes, and discordant homes.”

Under Dorsey’s leadership, the committee studied the need for recreational facilities such as playgrounds and indoor community centers as well as the need to diminish students’ heavy loads of homework and activities to allow them and their parents to address home and community problems. She was recognized for helping improve the health of schoolchildren, accomplishing beneficial reforms for the city’s public school system, and seeking to address such problems as the need to house the ever-increasing number of children moving into the district.

Dorsey received her third four-year contract in January 1928 with a salary of $12,000 ($218,000 in today’s money) and a stipulation that she could leave the school district before the end of her term. Indeed, she later announced her retirement effective in January 1929. With this announcement, she was hailed as “for the past ten years been considered the outstanding woman in the educational world on this side of the Atlantic” and “one of the most famous women in recent generations to claim Penn Yan and Yates county as her birthplace.”

The cornerstone for Susan Miller Dorsey High School was laid in December 1936, and the school opened the following September. Dorsey died on February 5, 1946 at age 88 – less than two weeks shy of her 89th birthday – at Wilshire Hospital in Los Angeles, where she had been a patient for a short time following an illness. During one of her last public appearances on January 17, she spoke before the board of education in favor of character training for young people and joked that her greatest mistake was resigning, since she no longer could work as closely with the students, which was her chief interest in life.

#historyblog#history#museum#archives#american history#us history#local history#newyork#yatescounty#pennyan#jerusalemny#losangeles#california#school#schooldistrict#publicschool#education#teaching

0 notes

Text

Did Yates County used to have five villages?

By Jonathan Monfiletto

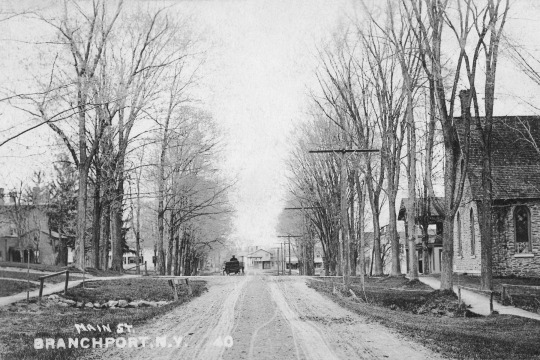

I would like to think the answer to the question I have posed in the title of this article is a resounding yes. After all, the Penn Yan Express of July 24, 1867 contained an item titled “Incorporated” and including the following declaration: “The village of Branchport has been granted a Charter and is now, as we understand, an incorporated village, in accordance with the vote of its citizens as announced in this paper two or three weeks since.”

Penn Yan became Yates County’s first officially incorporated village in 1833; Dundee became the second in 1848. Rushville followed in third in 1866; Dresden incorporated as the fourth – as far as I know – the next year. Indeed, the “Incorporated” item goes on to state: “Dresden is also aspiring to the dignity of an incorporated village, having voted in favor of incorporation at a late election.”

Regarding the vote in Branchport, the Express of July 10, 1867 indicated such an election took place in Branchport the Saturday before. “There was little or no opposition to the movement – the question being carried unanimously in the affirmative,” the newspaper stated in a “Branchport Items” column. “There is a good deal of enterprise and public spirit in Branchport, and this move is one that will add to the growth and thrift of that already thriving village.”

As delightful as these snippets are to uncover and peruse, the major problem with them – and it is a major problem in my mind – is they seem to be the only hard evidence I can uncover with regard to the idea (or fact?) that Branchport once existed as an officially incorporated village. Now a hamlet of the town of Jerusalem at the tip of the west branch of Keuka Lake, Branchport was once a thriving commercial area – as many small communities once were – and may have been its own village as well. However, to say the evidence is confusing and contradictory is about the same as saying the sky is blue and the grass is green. Yes, of course it is.

I located these items from the Express through our digitized newspaper database, which is hosted online through New York State Historical Newspapers (https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/). Yet, among the more than 700 results I browsed, I found neither proceedings of any Branchport village boards nor results of any Branchport village elections. A typewritten history of Branchport from our subject files asserts the village incorporated in 1867 and elected a president (a position similar to the office of mayor) and trustees on an annual basis. Another typewritten document from the files lists some of the “known presidents of the village”: Robert German in 1873, William Rynders in 1874 and again in 1881, Charles Hibbard from 1875 to 1876, and John L. Bronson in 1882.

Again, that seems to be the only hard evidence I can find to point to Branchport having been a real village (Pinocchio just exclaimed, “I’m a real boy!” in my head) at one point in time. Among the said 700-plus search results – using “village of Branchport” and “Branchport village” as keyword terms – nearly all of them reference a village of Branchport but seems to show it as nothing more than a wooden village (yes, a lame analogy with another Pinocchio reference), using village as a colloquial term. I have found similar references to the village of Bellona from sources who know Bellona is just a hamlet – a major one at that, having been settled around a stagecoach stop halfway between Geneva and Penn Yan – and not a village within the town of Benton.

Still, among those 700-plus search results are a few that seem to assert Branchport was indeed a real village, though to me they lack the smoking-gun hard evidence to make that a certain fact. For example, an article in the Yates County Chronicle, profiling 84-year-old Samuel Davis as one of the oldest residents of Jerusalem, contains an interesting parenthetical thought, noting Davis came to Jerusalem at the turn of the 19th century when “not a tree was cut in the vicinity of that somewhat assuming, (incorporated!) but moderate village of Branchport.” A letter to the editor in the Express in June 1874 references a meeting of the Board of Excise of the Village of Branchport during which the board granted a liquor license to a local drug store but denied the same to the Branchport Hotel. In December 1874, the Board of Health of the Village of Penn Yan banned residents of the village of Branchport from entering Penn Yan because of a small pox outbreak in Branchport.

These latter references are not alone in mentioning groups – including the Jerusalem Town Board, the Branchport Fire District, and the local Republican Committee – that met in, or discussed matters related to, a supposed village of Branchport or in mentioning a supposed village of Branchport alongside Yates County’s other villages. The Dundee Observer of June 8, 1881 listed population numbers for Yates County and its communities according to the 1880 U.S. Census; 271 people called Branchport home at that time. While there is an asterisk next to unincorporated villages – Bellona, Himrods’ Corners, and Eddytown among them – Branchport has no such asterisk, indicating it was an incorporated village. Proposed enlargements of the boundaries of the village of Penn Yan, considered by the New York State Legislature at various points, list the village of Branchport in relation to Penn Yan’s borders.

According to the November 22, 1882 edition of the Express, Louisa J. Wagener sued the village of Branchport after suffering an injury during a fall caused by ��� according to her argument – a defective or faulty sidewalk. “The injury sustained was the dislocation of the right shoulder joint, or the fracture of the neck of the scapula, by reason of which the use of the arm has been seriously and permanently impaired,” the newspaper noted in reporting the court awarded Wagener $2,000 (just over $64,000 in 2023 dollars). I threw the quote in for the shock value, but the item seems to indicate the village of Branchport was a real entity since only real entities can be sued. On the other hand, August 18, 1886, a publication called The Pioneer carried – on the same page – sketches titled “Village of Middlesex” and “Village of Branchport.” Since Middlesex has never been an incorporated village, though there is a hamlet of Middlesex Center, that image leads me to believe Branchport was never a truly incorporated village either.

On October 14, 1891, the Express carried the statistics for Yates County from the Census of the prior year. Branchport gained two more people for a population of 273, and once again the list seems to indicate it was an incorporated village. In fact, only the county’s nine towns and five incorporated villages are included; the list contains no other hamlets or communities. Indeed, October 6, 1897, while celebrating the opening of the Penn Yan, Keuka, Park, and Branchport Railway, the Chronicle published a brief history of the village of Branchport, noting: “In 1867 the village became incorporated, taking upon itself certain municipal characteristics that its local affairs might be ordered and governed independent of the township of Jerusalem, of which it forms a part.” Apparently, the village of Branchport was separate from the town of Jerusalem at some point and for at least three decades.

Over time, there are numerous seemingly colloquial references to the village of Branchport, where the newspaper calls the community a village but it isn’t necessarily an incorporated village. In October 1907, residents there started the Branchport Village Improvement Society, but whether they lived in an actual incorporated village then is unclear. Likewise, the Branchport Chamber of Commerce formed in March 1920 to oversee the community interests of the village of Branchport. When the Yates County Board of Supervisors established more county highways in March 1913, it referred to roadways in the village of Branchport.

When Yates County celebrated the 150th anniversary of the Sullivan Expedition in 1929, there was a general committee to oversee the county’s part of the commemoration in Geneva. Then, there were 14 smaller committees – one for each town and village – to oversee the festivities within its borders. That count includes committees for nine towns and five villages – with Branchport listed among the villages that exist today. So, Branchport may have been an incorporated village then, but the only record of an election taking place there that I could find was the vote to create the Branchport Fire District in 1933. Still, a report on the Jerusalem town budget in 1953 showed there were separate tax rates for the village of Branchport and for the town at large, indicating Branchport was a separate taxing entity and perhaps an incorporated village. Five years later, though, a legal notice referred to the hamlet of Branchport as the location of the Jerusalem town office.

In the 1960s, reports of a proposal for the town of Jerusalem to establish a water district in Branchport refers to the community as a village. A 1978 listing of deed transfers also refers to the village of Branchport alongside Yates County's other villages.

Branchport, of course, is no longer – if it ever was – an incorporated village and nowadays is considered a hamlet of the town of Jerusalem. Was Branchport ever an officially incorporated village? Looking at the evidence through more than 100 years of newspapers, part of me believes it was once a village and part of me thinks it never was a village. Can anyone out there shed some light for me?

#historyblog#history#museum#archives#american history#us history#local history#newyork#yatescounty#jerusalemny#branchportny#village#town#county#hamlet

1 note

·

View note

Text

Taking matters into their own hands

By Jonathan Monfiletto

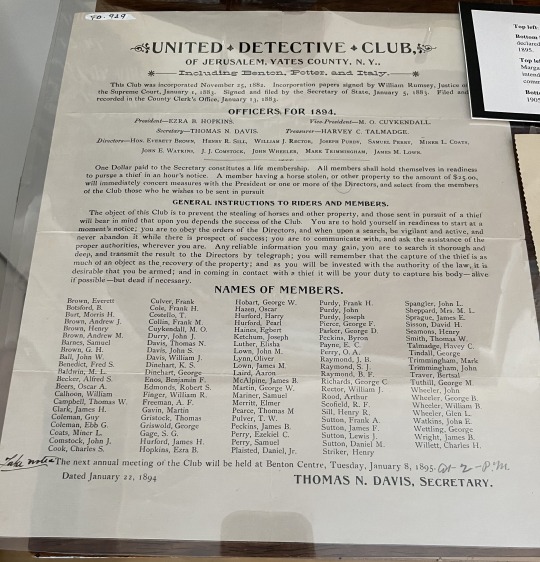

It is hard to tell whether the members of the United Detective Club actually went around fighting crime and catching bad guys or they were just a bunch of grown men playing cops and robbers and having a good time. I really would like to know more about this group.

In the collection of the Yates County History Center is a broadsheet document listing the officers and members of the club for 1894, apparently following the annual meeting for that year, and describing the club’s mission and objectives. By this point, the club was nearly a dozen years old, having incorporated on November 25, 1882 according to the document. In January 1883, the incorporation papers were signed by the New York State Supreme Court, signed and filed by the New York Secretary of State, and filed and recorded in the Yates County Clerk’s Office.

According to this document, the mission of the club was “to prevent the stealing of horses and other property,” and members paid $1 for a life membership. That membership obligated members to “hold themselves in readiness to pursue a thief in an hour’s notice.” Any member having a horse or property valued at least $25 stolen would alert the officers of the club and could select from among his fellow members “those who he wishes to be sent in pursuit.”

“…those sent in pursuit of a thief will bear in mind that upon you depends the success of the Club,” the document states. “You are to hold yourself in readiness to start at a moment’s notice; you are to obey the orders of the Directors, and when upon a search, be vigilant and active, and never abandon it while there is prospect of success; you are to communicate with, and ask assistance of the proper authorities, wherever you are.”

Members in pursuit of thieves were to follow any clues and exhaust any leads and apprise the club officers of their progress. Members would be “invested with the authority of the law,” according to the document, and should be armed.

“[Y]ou will remember that the capture of the thief is as much of an object as the recovery of the property,” the document states. “…in coming in contact with a thief it will be your duty to capture his body – alive if possible – but dead if necessary.”

As of 1894, the United Detective Club boasted 104 members; among the membership were four officers – a president, vice president, secretary, and treasurer – and 11 directors. The full name of the club, according to the document, was United Detective Club of Jerusalem, Yates County, NY with “including Benton, Potter, and Italy” listed on the document under the name of the club. Why Barrington, Middlesex, Milo, Starkey, and Torrey weren’t included, I’m not sure.

I’m also not really sure what the club was truly about. The digitized pages of our Yates County newspapers provide no coverage of the club or its members beyond announcements before and after its annual meetings, and even those are brief reports. If the United Detective Club actually participated in any activities of law enforcement, then it either eschewed mention in the newspapers or its pursuits weren’t considered newsworthy. The earliest mention of the club I could find in the newspapers, in fact, comes about a year after its incorporation, when the Penn Yan Express of December 27, 1882 carried a notice of a club meeting to take place on January 10, 1883 at Barrow’s Hall in Kinney’s Corners.

“The object of the meeting is to protect its members from the depredations of thieves,” the notice reads. Another thing I’m not sure about: whether criminal activity was that rampant in Yates County at that time.

The next mention doesn’t come until the Yates County Chronicle of February 7, 1894 with coverage of the annual meeting and election of officers as stated in the document from our collection. Four years later, the club seemed to step things up by gathering at the Knapp House in Penn Yan for its 1898 annual meeting. In 1900, the annual meeting took place at Cornwell’s Opera House in Penn Yan. By the way, none of the reports of these meetings divulge any details about the club’s activities.

The Chronicle’s report of the 1902 meeting doesn’t list where it took place but simply states, “The reports of the secretary and treasurer were satisfactory, showing a goodly increase in membership.” A report in the Express in December 1902 gives the number of members in the club, but the number is illegible on the digitized page – 100-something.

The club returned to the New Knapp House in Penn Yan for its 1903 meeting. In the report of that meeting, we learn: “The object of the club is to prevent the stealing of horses and other property. It numbers about 150 of the most prosperous farmers in the four towns represented.” The club gathered at the New Knapp House again in 1904, but we still don’t learn any specific details of its specific activities.

Aside from the “A Glance Backward” feature in The Chronicle-Express of September 19, 1940 listing a United Detective Club meeting from 50 years before, the 1904 meeting is the final newspaper mention for the club. It is possible it was around only for those 20 or so years.

What did the United Detective Club do, and what as its purpose? Did its members really go about trying to capture thieves and recover stolen property? Or did they just like getting together every year or so and having a good time?

#historyblog#history#museum#archives#american history#us history#local history#yatescounty#pennyan#newyork#uniteddetectiveclub#jerusalemny#bentonny#potterny#italyny#law enforcement#detective#horse stealing#stolen property#theft

1 note

·

View note

Text

The poor shall inherit the mansion

By Jonathan Monfiletto

For nearly 100 years, from just a few years after Yates County was formally established until the early 1920s, the Yates County Poor House – with a 200-acre farm whose products helped finance the cost of its operations and maintenance – stood, appropriately enough, on County House Road in the town of Jerusalem. In June 1922, though, a fire destroyed the nearly 50-year-old building, newly built in 1877, and the 34 inmates at the time were relocated to county homes in nearby counties.

Of course, that meant the county needed a new home for its “unfortunate and indigent” residents, as the original resolution stated the home’s purpose. The county Board of Supervisors soon had its answer in one of the most elegant mansions overlooking the west branch of Keuka Lake. A month after the fire, according to an article in the July 14, 1922 edition of the Penn Yan Democrat, the board closed a deal with Clinton B. Struble to purchase the Esperanza property near Branchport for $30,000.

The board met at a special meeting on Saturday, July 8, 1922 to approve the purchase, which it did in an 8-1 vote. According to the July 14, 1922 edition of the Rushville Chronicle & Gorham New Age, the supervisors gave their approval after “a thorough investigation of Esperanza” in company with Dr. Hill, of Albany, Superintendent of the New York State Board of Charities. Dr. Hill had inspected the buildings and property two days before and approved of the location. He promptly submitted the proposition to the State Board for a final decision.

Dr. Hill “seemed well pleased with Esperanza,” according to the Rushville Chronicle, but informed the supervisors they should plan on a building with fireproof walls and floors if they decided to rebuild on the site of the former county home. Planning to accommodate up to 50 inmates, such a project could cost close to $100,000 ($1.8 million in today’s money). Meanwhile, Struble had offered Esperanza – a home that “has been for sale for a long time,” according to the Democrat – to the county for much less than the cost to reconstruct the former home.

The purchase included the mansion home and about 50 acres of land, a packing house that could be used as a hospital for tuberculosis patients, and a reservoir that supplied ample water to the home. The sale did not include a vineyard or lakefront property. A noted advantage of the property was its location along a state road with daily trolley service along the Penn Yan, Keuka Park, and Branchport Railway. Because of this, the home was easily accessible to and from Penn Yan and Branchport.

The county planned to take possession of Esperanza on August 1. The Colonial-style mansion, according to the Democrat, contains 15 rooms with 12-foot ceilings. Before any inmates moved in, however, the county needed to install plumbing, electric lights, and a heating plant. The heating boiler from the former home was to be used, and electric current could be drawn from the trolley. Some of the rooms were to be divided by partitions to accommodate 40 inmates. Work began in October 1922, according to the May 4, 1933 edition of The Chronicle-Express, and finished within a year.

According to an article in the December 13, 1922 edition of the Yates County Chronicle, the construction involved additions and alterations such as a 20x65 dormitory, a 27x28 annex, and laundry cement cisterns as well as interior work. A balcony was built over the front porch, and the interior was remodeled according to the standards of the state for bathrooms, sleeping rooms, library, kitchen, and dining rooms to “provide the greatest possible comfort and safety of the occupants,” reported The Chronicle-Express.

B.F. Rogers, the contractor for the project, expected to have the building ready for occupancy by March 1, 1923 and completed by June 1. When complete, the building was to have room for 34 men and 21 women and “will be an ideal county home,” according to the Yates County Chronicle.

Rogers’ contract amounted to $37,300 and called for the complete work of the building and the heating and lighting equipment. The Yates County Chronicle reported supervisors had authorized the county treasurer to borrow $50,000 to complete the new county home. The county planned to offset the cost of the purchase and the construction by selling the property of the former county home. The barns and the walls of the home were left standing after the fire, and a tenant house and barn across the road also made up the altogether 215 acres of the property.

After almost a century on the road named for its location, the county house at Esperanza lasted just 25 years. According to a November 13, 1947 newspaper article, the supervisors authorized the welfare commissioner at Esperanza to discontinue the county home. The commissioner had previously been authorized to take no more admissions; there were only two inmates at the time, yet the house was kept up with the help of a housekeeper, a cook, and a furnace man who doubled as caretaker.

The commissioner had been placing other inmates, previously housed at Esperanza, in outside venues for several months. The county had found it was less expensive to have its needy residents cared for in private homes or nursing homes than to keep up the buildings and grounds at Esperanza.

On December 31, 1952, the supervisors approved selling the 50-acre site with three homes and a barn to Roger Fulkerson, of Starkey, for $11,200. The Fulkersons’ plans for the property went undisclosed at the time. However, the following month, the county attorney deemed that sale illegal, citing a recently enacted law requiring county-owned property to be sold through certain procedures involving a publicly advertised sale.

Thus, the supervisors authorized a public auction sale to take place January 19, 1953 on the steps of the county courthouse, with the Esperanza property being sold to the highest bidder. No bid could be refused at that time, though irresponsible bidding was mitigated with a requirement that 10 percent of the amount of the bid had to be posted at the time of its acceptance at the sale.

Garrett E. Bacorn, of Elmira, became the new owner of the Esperanza property with a winning bid of $12,500. He already owned the site of the former county home on County House Road and had extensively improved that property. At the time, Bacorn said he had a large family and would keep Esperanza for private use.

At the time of its sale, Esperanza had stood empty for five years. Now, the property went back into the hands of a private individual and onto the tax rolls for the first time in 30 years.

#historyblog#history#museum#archives#american history#us history#newyork#local history#yatescounty#jerusalemny#countyhouse#esperanza#keukalake

1 note

·

View note

Text

How Yates County’s towns got their names

By Jonathan Monfiletto

Maybe I’m just a nerd (OK, I am a nerd and I admit it, but that’s beside the point right now), but I enjoy learning the origins and meanings of various words and phrases in the English language. That is particularly true when it comes to the origins of place names; I love knowing how certain communities around our state and country came to be called the names that they have.

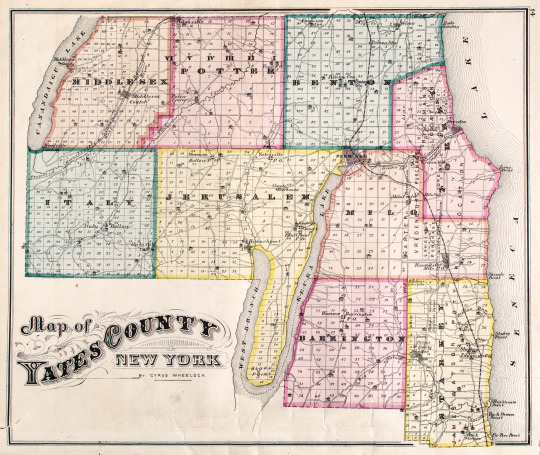

So, especially as Yates County marks 200 years it was formally separated from Ontario County and established as its own county on February 5, 1823, I wanted to investigate the origins of the names of the nine towns in the county. Some of the towns, I already knew where the name came from; others of the towns, I thought I knew how they got their names. In both cases, I wanted to compile the official record of the namings as best as I could.

At first, I consulted former Yates County Historian Frances Dumas’ book “A Good Country, a Pleasant Habitation,” as I thought I had read a certain origin story in that book only to realize later I had seen it somewhere else. Though I did find several records of name origins in that book, when I couldn’t find a precise story, I look through our subject files on the individual towns. I even cracked open Stafford C. Cleveland’s “History and Directory of Yates County” to see what he had to say.

Then, of course, when I was researching a different topic in our collection of digitized newspapers, I came across an article written by Walter Wolcott – a historian of Penn Yan and Yates County – and published in several local newspapers in December 1920. The article is titled “How Names of Towns Originated: Names of the Nine Townships in Yates County Have Interesting History Information.” Voila, eureka, exactly what I was looking for.

With the information from Wolcott’s article and through research of my own in other sources, I now present the origins of the names of the nine towns in Yates County. Akin to what a playbill would do, I present these towns in the order of their incorporation.

Jerusalem, established as a town in what was then Ontario County in 1789, probably has the most well-known, and thus easiest to find out, origin story. As most people know, the Society of Friends, which followed the Public Universal Friend and became the first group to settle what is now Yates County, had a vision to create what they called the New Jerusalem – a place where they could set up their homes, their businesses, and their community. Though the territory of the current town is not where the Friends first settled, it is where the majority of the sect ended up and took its name for the vision they had for their community.

Middlesex was also organized as a town in 1789, shortly after the first permanent non-native, European settlers arrived on the western shore of Seneca Lake. However, at first it was called Augusta, though any source I consult indicates no one knows why that name was given. It seems another town in Oneida County took that name (possibly after this town was formed and possibly after a General Augustus VanHorn), so this town renamed itself Middlesex in 1808. This name apparently came from Middlesex County, Massachusetts where many of its settlers came from.

Benton was formed out of Jerusalem in 1803, though it originally was named Vernon (except a town in Oneida County took that name the year before) and then Snell (after Jacob Snell, a State Senator from Montgomery County who had no apparent connections to this part of Ontario County). It wasn’t until 1810 the town took on its current name; it could have been after Caleb Benton, who bought the title to this township and built a sawmill on Kashong Creek, or it could have been after his cousin Levi, to whom Caleb eventually sold the land. My sources point to Levi as the namesake.