#max scheler

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Max Scheler

Power-Line Construction , Location Unknown , 1952

505 notes

·

View notes

Text

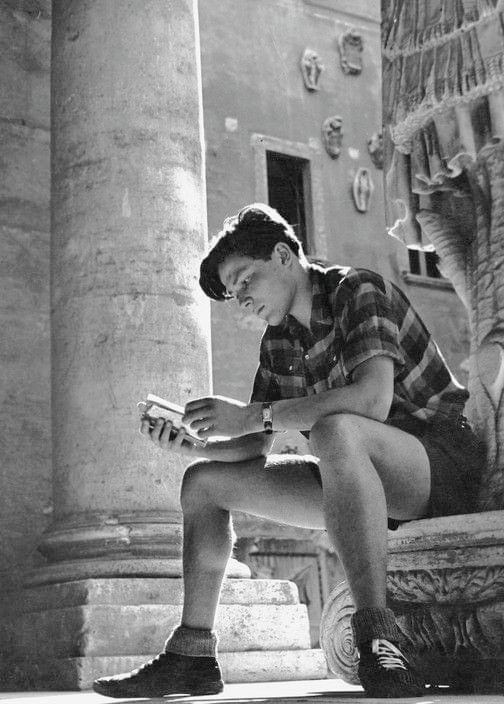

ᴍᴀx sᴄʜᴇʟᴇʀ ᴀᴛ ᴛʜᴇ ᴘᴀʟᴀᴢᴢᴏ ᴅᴇɪ ᴄᴏɴsᴇʀᴠᴀᴛᴏʀɪ ᴄᴏᴜʀᴛʏᴀʀᴅ ɪɴ ʀᴏᴍᴇ, ɪᴛᴀʟʏ. 𝟷𝟿𝟺𝟿. Photography by Herbert List.

#max scheler#herbert list#1940s#vintage#architecture#nostalgia#queer#20th century#guys#art#books and reading#wanderlust#travel#explore#ancient rome#art history#bookish#people#vintage men#italy#📚

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

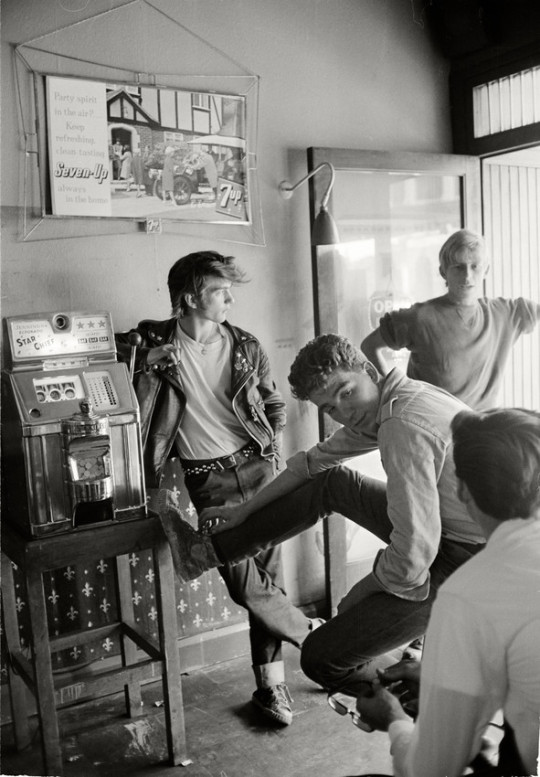

Max Scheler, Montenegro, Photo by Herbert List, 1952

Interesting note: Max Scheler inherited List’s body of work in 1975 and was instrumental in saving and promoting it.

228 notes

·

View notes

Text

“El hombre se ha hecho plena, íntegramente problemático; ya no sabe lo que es, pero sabe que no lo sabe”

Max Scheler

Fue un filósofo alemán, nacido en Múnich en agosto de 1874, de gran importancia en el desarrollo de la fenomenología, la ética y la antropología filosófica, además de ser un clásico dentro de la filosofía de la religión.

Max se bautiza en la iglesia católica, su padre era protestante y su madre judía.

Al finalizar sus estudios básicos, se matricula en la Universidad de Múnich pero al siguiente año decide trasladarse a la Universidad de Berlin para estudiar filosofía y sociología.

En 1897 presenta su tesis doctoral dirigida por Rudolf Eucken, quien fuera galardonado con el Premio Nobel de Literatura en 1908.

Su escrito “El método trascendental y el psicológico” le hace merecedor del nombramiento de docente en la Universidad de Jena y es en 1902 cuando conoce al filósofo y matemático alemán Edmund Husserl.

El encuentro con Husserl le hace quedar marcado por el denominado método fenomenológico (el estudio filosófico del mundo, a través directamente de la conciencia).

Derivado de un escándalo provocado por su esposa, de conducta inmoral, Scheler se ve obligado a abandonar la docencia y se traslada a Berlín en donde con el apoyo de sus amigos y de su incansable capacidad de trabajo, permitió que afloraran la mayoría de sus mejores y más importantes obras.

Scheler se divorcia de su esposa y contrae matrimonio civil con su alumna María Scheu, en donde fue considerado como apóstata por los creyentes y cristiano disimulado por los si creyentes.

Dentro de algunas de las instituciones más importantes destacan; “El resentimiento de la moral” (1912), “Los ídolos del conocimiento de sí mismo” (1912), “El formalismo en la ética y la ética material de los valores” (1913), “Muerte y supervivencia” (1911-1914) entre muchos otros.

Es muy difícil pensar en gran parte de la ética, de la psicología o de la antropología del siglo XX sin la influencia de Scheler. Sus aportaciones en la filosofía de la religión, y en la Teología moral fueron decisivas.

Se han distinguido tres etapas en la vida de Scheler y en su posición doctrinal. Durante su juventud estuvo dominado por la influencia de Eucken, después seguirá la influencia fenomenológica de Husserl, sin perder sus aficiones vitalistas y afectivistas de Eucken, y su madurez por su posición teista.

La filosofía de Scheler considera fundamentalmente tres problemas o cuestiones dobles; el conocimiento, y los valores, la vida y el hombre, los sentimientos y Dios.

La persona es para Scheler esencialmente espiritual. El espíritu no es, propiamente, ni la inteligencia ni la voluntad: es más bien un principio nuevo. El acto de separar la existencia y la esencia constituyen la característica diferencial del espíritu humano. En conjunto, el espíritu de la objetividad.

A cada persona corresponde un mundo y a cada mundo una persona, en donde la persona-individuo se articula en una comunidad.

El hombre como realidad natural no escapa a su animalidad, pero el hombre también tiene otro sentido: es el ser que ora, que aspira a trascender; es el buscador de Dios. En donde Dios es un ser vivo y personal.

Max Scheler muere en Fráncfort de Meno en mayo de 1927 a la edad de 52 años.

Fuentes: Wikipedia, filosofía.org

#max scheler#notasfilosoficas#citas de reflexion#citas de filosofos#frases de filosofos#filosofos#alemania#citas de escritores#notas de vida#frases de reflexion

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is the hedonist escape from suffering any better? The hedonist attempts by sheer will to accumulate a surplus of pleasure. But already earliest Greek thought did not support this teaching. Not Aristippus, or the pessimist Hegesias, who urged his students to commit suicide (peisithanatos), or Epicurus, who, in place of the positive, sensual maxim to have pleasure in the present, which Aristippus taught was the highest good, preferred mere lack of pain and equanimity (ataraxia), was able convincingly to justify hedonism.

The historical reversal of the hedonist system into the most bleak pessimism is only one concrete example of an interior law of the spirit, "There are things that do not occur when consciously sought," and its corollary, "There are things more likely to occur the more a person strives to avoid them." Happiness and suffering are such things. Happiness always flees to greater distances from one who seeks it. Suffering approaches the fugitive more quickly the more rapidly he flees. This is especially true for deeper feelings.

Aristippus began his teaching by claiming he did not aspire after riches, horses, or women but only his pleasure in them. He taught that only a fool strives for things and goods, the wise man for his pleasure in things and goods. Thus, Aristippus transformed the abundance of the world and the value of its contents into a poor, bare scaffolding for the pleasures of his flesh. He did not acknowledge that, in forming and contemplating this world with love, happiness would bloom, as it were, as a blessed by-product and reaction. He never asked whether his cherished lover loved him in return; nor, when he ate a fish, whether he was tasty to the fish, but only whether the fish was tasty to him!

However, Aristippus was the fool. Without intending to, he removed the ground on which the bloom of happiness grows by withdrawing any free, loving, and active submission to the world or to the loved one. He did not see that pleasure, especially of the greater kind, is found only if a person does not actively seek pleasure, but seeks its content and inner value. He also did not see that the core of happiness in love can be found only by turning away from oneself and surrendering to a subject who responds in love to the love given. He did not grasp the firm law of life that the practical effort to win happiness steadily lessens the permanence and depth of happiness if will and action are geared solely to achieving it, for strictly speaking only sensual pleasure can be practically realized. He did not notice that pain is intentionally avoidable only to the extent it is near the peripheral zone of the senses. And he did not recognize that the suffering involved in continually avoiding pain inevitably becomes more dreadful as a result of ones heightened sensitivity to pain. He did not see the basic fact that the emotions should be sources, symptoms, and gifts, rather than objects, of willing. Thus, his technique of feeling suffering ends inevitably in a longing for death.

Max Scheler, “The Meaning of Suffering”, translated by Harold J. Bershady, from On Feeling, Knowing, and Valuing

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

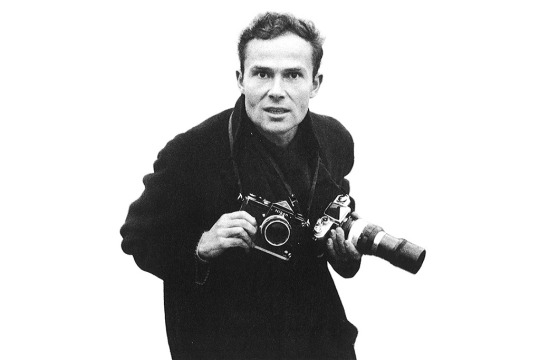

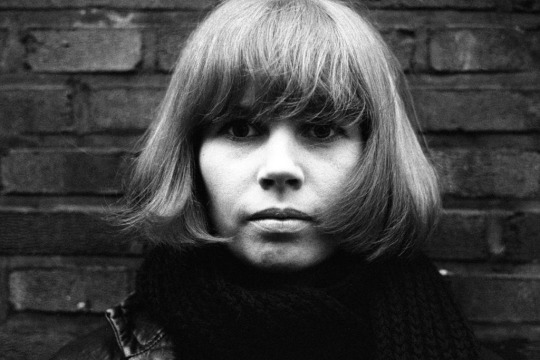

Max Scheler and Astrid Kirchherr

-

INT: How did you collaborate with Max Scheler?

KIRCHHERR: In the Sixties Max was one of the most important photographers. For example he took pictures of the first transplantation of a heart living for for weeks in quarantaine with the patients. He was working for the Stern, later becoming the editor in chief of the magazine GEO. Together with him I was at the setting for A Hard Day’s Night in 1964.

INT: How did it get to this?

KIRCHHERR: Brian Epstein did not permit photographers. I called George because Stern magazine asked me to be the door opener. George said: 'I will talk to the others. According to me it’s okay when you come to London and take pictures. But they have to pay you, otherwise they may stay at home.' Max gave me a small camera which I never had worked with before. And there were some fine pictures as a result. Especially the pictures of children in Liverpool. Some of them looked really looked like figures in a Charles Dickens novel. (Interview with Astrid Kirchherr)

-

(The following is an Interview with Ulf Krüger, Astrid’s business partner and manager, from 'Astrid Kirchherr: A Retrospective'.)

INT: Did the feature in Stern magazine raise awareness of Astrid’s photography when it was published in 1964?

Krüger: No, because that’s another story. Astrid was not famous as a photographer then but she was working as an assistant for a really famous photographer, Reinhart Wolf. Stern magazine asked Max Scheler, who was the chief photographer for Stern, to go to England to cover the filming of A Hard Day’s Night and go to Liverpool and see The Beatles. That was their rough idea, but in 1964 The Beatles, already at the top of their career, wouldn’t have reporters of any magazine at the time of filming. So Reinhart Wolf recommended Max (they were friends) ask Astrid to be a sort of ‘door opener’, not a photographer. To cut it very short, Astrid called The Beatles and asked if it was possible to have coverage and The Beatles said yes as long as she was part of it they could do it. So Astrid went to England with Max, but he was the photographer and Astrid was the ‘door opener’. Of course Max knew she was a photographer and gave her a camera and she took a lot of photos as well but she didn’t have the job from Stern magazine. When Astrid had shot film she gave the film to Max because he was the boss and Max gave all the films to Stern with his stamp on. So the articles in Stern magazine don’t mention the credit Astrid Kirchherr, it’s all Max Scheler.

…

I found out where Max was living, called him, explained who I was and asked him why he had Astrid’s photos printed with his credit, and he told me he really didn’t know about that but acknowledged that I was right. He had sent all the films to Stern magazine and it was a Max Scheler thing so the credit was always Max Scheler. He apologised and asked to meet to return the negatives to Astrid which was great. So we met and Astrid and Max sorted out the photos and so the beautiful photos with the Liverpool kids ended up being Astrid Kirchherr copyright. Nice story.

INT: Do you think the issues you confronted as Astrid’s manager were connected to her working as a female photographer at that time?

Krüger: I think it had a lot to do with that, especially being a special woman. Astrid used to dress in a special way when she met The Beatles, wearing leather trousers, leather jackets and things like that. That was really unusual for a young woman in Germany and I’m quite sure it was unusual in England as well, or in Japan or wherever. So, one one hand, she was special, maybe people were even a bit frightened because she was self-conscious and things like that. On the other hand, she was just a woman because business was dominated by men then, still is, and so that’s one of the additional problems I think. They only liked the Beatles photos because they couldn’t realise that a photo of Rory Storm for example is a beautiful classical shot, they didn’t realise it because it was not a Beatle and that could disappoint an artist heavily I think. So that’s how it was, still it’s a bit discriminating. Women are not paid like men, are not respected like men in many cases, and that’s not good, and it was much worse then.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

El hombre posee un Dios o un ídolo.

— Max Scheler

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

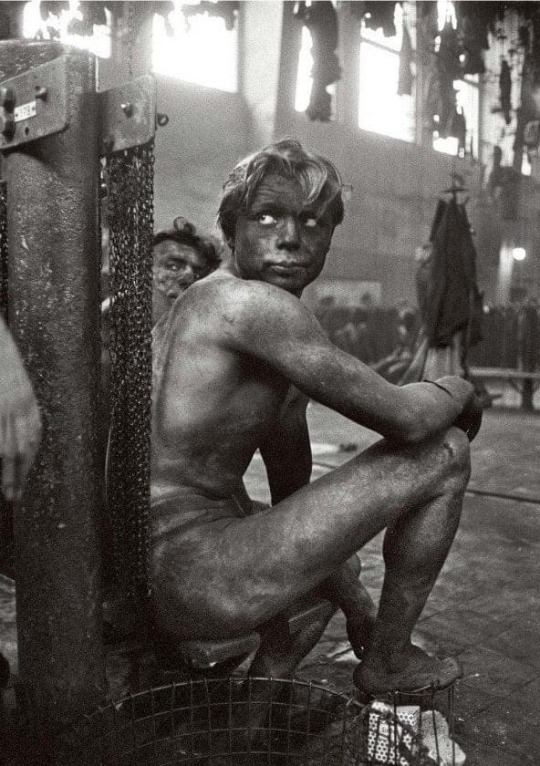

Max Scheler (alemão, 1928-2003)

mineiro de carvão esperando para entrar no chuveiro comunitário no final do turno, Gelsenkirchen, Alemanha, 1958

Max Scheler (German, 1928-2003), Coal miner waiting to get into the communal shower at the end of his shift, Gelsenkirchen, Germany, 1958

#max scheler#coal miner waiting to get into the communal shower at the end of his shift#gelsenkirchen#germany#1958

366 notes

·

View notes

Text

Max Scheler y Su Jerarquía de Valores: Una Mirada a la Ética Fenomenológica

#ética material de los valores#crítica al hedonismo#fenomenología de los valores#filosofía contemporánea#filosofía de la religión#influencia de Max Scheler.#inteligencia emocional en ética#jerarquía axiológica#valores espirituales y religiosos

0 notes

Text

Max Scheler

Habitation , Location Unknown , 1952

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Astrid Kirchherr and George Harrison, Green Street, London, March 1964; photo by Max Scheler.

"George always wanted to know how you were, how you were feeling." - Astrid Kirchherr, Liverpool Echo, November 30, 2001

#George Harrison#Astrid Kirchherr#quote#quotes about George#1964#1960s#1970s#1980s#1990s#2000s#The Beatles#George and fame#fits queue like a glove

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

Untitled, Italy, Photo by Max Scheler, 1950s

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

“La última meta del ambicioso no es adquirir una cosa de valor, sino ser más estimado que otros”

Max Scheler

Fue un filósofo alemán, nacido en Múnich en agosto de 1874, de gran importancia en el desarrollo de la fenomenología, la ética y la antropología filosófica, ademas de ser un clásico dentro de la filosofía de la religión.

Max se bautiza en la iglesia católica, su padre era protestante y su madre judía.

Al finalizar sus estudios básicos, se matricula en la Universidad de Múnich pero al siguiente año decide trasladarse a la Universidad de Berlin para estudiar filosofía y sociología.

En 1897 presenta su tesis doctoral dirigida por Rudolf Eucken, quien fuera galardonado con el Premio Nobel de Literatura en 1908.

Su escrito “El método trascendental y el psicológico” le hace merecedor del nombramiento de docente en la Universidad de Jena y es pen 1902 cuando conoce al filósofo y matemático alemán Edmund Husserl.

El encuentro con Husserl le hace quedar marcado por el denominado método fenomenológico (el estudio filosófico del mundo, a través directamente de la conciencia).

Derivado de un escándalo provocado por su esposa, de conducta inmoral, Scheler se ve obligado a abandonar la docencia y se traslada a Berlin en donde con el apoyo de sus amigos y de su incansable capacidad de trabajo, permitió que afloraran la mayoría de sus mejores y mas importantes obras.

Scheler se divorcia de su esposa y contrae matrimonio civil con su alumna María Scheu, en donde fue considerado como apóstata por los creyentes y cristiano disimulado por los si creyentes.

Dentro de algunas de las instituciones mas importantes destacan; “El resentimiento de la moral” (1912), “Los ídolos del conocimiento de si mismo” (1912), “El formalismo en la ética y la ética material de los valores” (1913), “Muerte y supervivencia” (1911-1914) entre muchos otros.

Es muy difícil pensar en gran parte de la ética, de la psicología o de la antropología del siglo XX sin la influencia de Scheler. Sus aportaciones en la filosofía de la religión, y en la Teología moral fueron decisivas.

Se han distinguido tres etapas en la vida de Scheler y en su posición doctrinal. Durante su juventud estuvo dominado por la influencia de Eucken, después seguirá la influencia fenomenológica de Husserl, sin perder sus aficiones vitalistas y afectivistas de Eucken, y su madurez por su posición teista.

La filosofía de Scheler considera fundamentalmente tres problemas o cuestiones dobles; el conocimiento, y los valores, la vida y el hombre, los sentimientos y Dios.

La persona es para Scheler esencialmente espiritual. El espíritu no es, propiamente, ni la inteligencia ni la voluntad: es mas bien un principio nuevo. El acto de separar la existencia y la esencia constituyen la característica diferencial del espíritu humano. En conjunto, el espíritu de la objetividad.

A cada persona corresponde un mundo y a cada mundo una persona, en donde la persona-individuo se articula en una comunidad.

El hombre como realidad natural no escapa a su animalidad, pero el hombre también tiene otro sentido: es el ser que ora, que aspira a trascender; es el buscador de Dios. En donde Dios es un ser vivo y personal.

Max Scheler muere en Fráncfort de Meno en mayo de 1927 a la edad de 52 años.

Fuentes: Wikipedia, filosofia.org

#alemania#max scheler#filosofia#catolicismo#alma#espiritu#notas filosoficas#filosofos#filosofando#citas de escritores#citas de filosofos#frases de filosofos#notas de reflexion#frases de reflexion

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Max Scheler, Ressentiment tr. Lewis A. Coser

I think we can all understand the example of Tertullian or the reactionary attitude. The claim about philosophical criticism also suffering from a degree of "ressentiment" is more puzzling maybe.

Is 'contrastive' thinking necessarily an expression of ressentiment? (e.g. If the flaws of B help me appreciate A more than I would have otherwise). Even if Scheler doesn't reach that conclusion, does he come a bit too close? Surely we're meant to appreciate the genuinely "resurrected" person in contrast to the vengeful type that Tertullian embodies.

In any case, I don't think I'm free from ressentiment myself, and certainly Scheler wasn't either at the time he wrote this, given his support for German aggression during WWI. Specifically his framing the conflict as a kind of spiritual struggle against English and French values if I remember correctly.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Max Scheler/BIO

Nascido como filho do filósofo Max Scheler sênior em Colônia, Alemanha, ele primeiro segue os passos de seu pai e se torna um estudante de história da arte, literatura alemã e inglesa na Universidade de Munique e mais tarde na Sorbonne em Paris. Durante seus estudos, ele também trabalha como assistente na estrada e na câmara escura do fotógrafo Herbert List, que ele conheceu durante a guerra em 1941. Sua primeira publicação de suas próprias imagens aparece em 1949.

Depois de se mudar para Paris em 1951 e conhecer Robert Capa, ele começou a contribuir com suas imagens para a nova agência de fotógrafos Magnum Photos em 1952. Já nessa época ele estava viajando pela Europa e Oriente Médio, frequentemente junto com seu mentor Herbert List.

Já em 1954 ele está se mudando novamente para Roma, onde ele está cobrindo principalmente eventos sociais, culturais e políticos na Itália e ao redor do Mediterrâneo, e agora está publicando em revistas como Picture Post (Londres), Paris Match (Paris), Look (Nova York), Münchner Illustrierte (Munique) e Epoca (Milão). Durante uma estadia de seis meses nos Estados Unidos em 1956, um portfólio e um retrato dele e de seu trabalho aparecem no renomado Yearbook of US Camera. Nos meses seguintes ele para de distribuir pela Magnum Photos e agora opera independentemente de 1956 a 1958 fora de Roma.

Nos dois anos seguintes, ele se muda para Hamburgo e começa a trabalhar exclusivamente para a revista Stern . Junto com a equipe de Robert Lebeck, Thomas Hoepker e Stefan Moses, seu estilo jornalístico influencia decisivamente a aparência da revista. Agora ele é um fotógrafo convicto de "interesse humano" e se concentra no comportamento e na emoção humana. Seus retratos de eventos históricos e a escolha do tema não apenas o apresentam como um cronista preciso de eventos, mas dedicado às suas consequências para o homem comum. Sua câmera observa felicidade e tristeza, empatia e desespero não apenas em tempos de guerra e crise, mas também na vida em geral.

O novo estilo da revista Stern permite que ele revisite países como Estados Unidos, França, Polônia, Vietnã, Coreia ou a RDA e crie ensaios de imagem em várias partes. Scheler frequentemente conta suas histórias enfatizando uma visão privada da vida cotidiana das pessoas nos países para os quais viaja. Mas ele também visita seus principais contemporâneos, como Charles de Gaulle, Ben Gurion e Nasser, Kennedy e Chruschtschow, Nixon e Johnson, Indira Gandhi e Allende, Willy Brandt, a rainha Elizabeth, o rei Hussein, o xá Reza Pahlavi ou o papa Pio XII e Paulo VI. Seus retratos refletem não apenas as emoções desses líderes, mas também os problemas de seu tempo.

Em 1975, Scheler muda de lado na publicação e se torna editor-chefe de fotografia para os recursos coloridos de Sterns . A partir de então, ele raramente usa a câmera para fins profissionais. Ele logo percebe que nem todas as grandes histórias coloridas se encaixam no perfil de Sterns e apoia a ideia de Rolf Gillhausen da revista GEO . Ele trabalha como diretor de fotografia e diretor de arte da GEO desde suas primeiras edições em 1976 até 1980 e, mais tarde, tem a mesma posição na revista de viagens Merian até 1992. Após a morte de Herbert List em 1975, Scheler herda sua propriedade e salva a obra de List de desaparecer no esquecimento. Ele edita vários livros e faz a curadoria de exposições do trabalho de List nas principais cidades da Europa e dos Estados Unidos. Max Scheler morre em fevereiro de 2003 após uma curta batalha contra o câncer. Ele está enterrado no Südfriedhof em Colônia.

Max Scheler

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Protective suits and Emergency Life Pack for an evening in New York, 1961. Photo by Max Scheler.

446 notes

·

View notes