#mino — a prelude to a boy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Oh yeah highlight of my night so far probably was when i booted up ultrakill 6-2 (with cheats so i could focus on rambling) so i could show my brother Gabriel’s voice lines in said chapter (i also rambled abt gabriel’s like. Lore and stuff. Mostly his overarching narrative presence in the other layers) (this happened because i mentioned one of gabe’s voice lines references a NIN song, my brother says he only listens to one NIN song, blah blah the stars aligned) and then he asked if he could fuck around in the next chapter w/ cheats on. I was like. Yeah sure go for it buddy. While holding back a big ol grin because it’s fucking 7-1. I only maybe really told him abt the basic mechanics in advance like how to shoot and how to punch/parry. It was extra fun when he thought the minotaur boss fight was over. Like. Surprise, bitch! Anyways yeah then i got him playing thru the game properly. Its been fun watching him so far actually he got to the end of 2-3 before tapping out bc he was tired. Do you know how much lore i got to ramble about. Do you. Win for me

#scov.txt#sorry for the longass rambly post#also i mean my ACTUAL brother. like. blood related legit sib#hes also WAY more confident than i am. up in fuckin cerberi faces punching them meanwhile theres me who stays as far away as possible#him preferring the shotgun whereas its the weapon i use the least. etc#i also p-ranked all of prelude finally and got most of limbo p-ranked (1-3 is LONG ok im doing that tmrw) so thats a win for me too#i got to express how mindflayer’s get pretty priviledge from me i got to tell him abt the horrors of humanity and war. etc etc#i also pointed out minos’ corpse during 2-2 and was like ‘you see him?’ ‘yeah?’ ‘hes a boss fight :)’#my brother is wholeheartedly the easiest guy i know to get into my interests. if telling him abt it doesnt work the. enticing him w/ -#- gameplay does. it’s amazing#*then enticing him blah blah blah. fixing my typo just specifying the placement#also the gabriel convo was like. i can’t remember how it STARTED but i remember how it got to the NIN thing#‘i think youd like gabriel tbh’ ‘i dont like robots-‘ ‘hes an angel’ ‘oh!’#also ‘i dont like robots’ um ok. robot game blast 💥💥💥💥#pretty sure he meant in a gay way but hey. robot game blast. learn the horrors of machinery boy

1 note

·

View note

Note

literally all of ultrakill lore

in the game, you play as the war machine named V1. you run on blood, and there is no blood left on earth. the humans, before going extinct, had found the gates to hell, and had a project called the “hell excavation and exploration project”. this project was abandoned for unconfirmed reasons, but it is most likely due to mankind discovering hells sentience. some robots from the final war, which was a war between humans on earth, like v1 and the sentries were sent to hell to help with the project. (although v1 specifically likely wasn’t used in it). in the first “act” of the game (it’s about the length of a layer but whatever) called the prelude follows v1 slowly getting closer to the gates of hell. there are some husks that have escaped hell. husks are the souls of sinful humans, manifesting their looks and strengths based off their lives. when v1 reaches the gates of hell, you can see the infamous “abandon all hope all ye who enter here” door from dante’s inferno, which ultrakill is heavily based off of. before entering hell, v1 needs to fight cerberus. not the three headed dog, it’s just a statue of some guy. also he has a orb of hell sauce or whatever and he uses it to Dunk on you.

LIMBO

limbo is the first layer of hell, and has the least severe punishment. limbo is for sinless people who didn’t believe in god, and for this they were put in a mock version of heaven, isolated from anyone else. however, they were able to go to the next layer to escape this. nothing too notable happens lore wise in limbo, (there is very minor stuff but who cares) the biggest thing is meeting v2 at the end of the layer. v2 looks the exact same as v1, but is now red and is very cool. (this is taken from memory so this might be wrong) v2, unlike v1, is not a war machine. v2 was created during the great peace, which was right after the final war. the great peace united all of humanity. why was v2 created? why did mankind make a robot that ran on blood during a time of peace? who knows. after beating the shit out of v2, v1 steals his arm and goes on to the second layer, lust.

LUST

lust is the second layer of hell, and according to king minos, the king of the lust layer, “the most bullshit one” (not his exact words). the punishment in lust is strong, cold winds. king minos believed that people shouldn’t be punished for only loving one another, so he starting creating a city for his people. the walls of the city would stop the winds. this started the lust renaissance, which the arch angel gabriel didn’t like all too much. (btw gabriel in the game is the judge of hell you’ll hear more about him later) gabriel decided in order to stop all of this, he would just kill king minos. minos’ husk walks around the layer of lust looking for sinners. at the end of the layer, we fight the corpse of king minos. once he is defeated, we enter his mouth to go to the next layer, which is gluttony.

GLUTTONY

gluttony is the third layer of hell, and the punishment is to slowly decay in acid. glutton is inside minos’ ultra-fucked up body. we see a bunch of eyeballs, teeth, and statues inside of him. there is a secret exit (that we will talk about later) inside this level. in the second and last level (the normal amount is 4) of gluttony, we get to see our boy gabriel. gabriel essentially says “hey get the fuck outta hell what are you doing here” but we are Chads and we continue onward, eventually meeting up with gabriel and fighting him. fun fact: gabriel’s weakness is nails, most likely a reference to that jesus guy. after fighting gabriel he gets all pissed, calls us an “insignificant fuck” then teleports away.

“May your L’s be many, and your bitches few.”

before continuing on to the next act, we need to talk about todays sponsor, raid shado-

before continuing to the next act, there is a cutscene that depicts gabriel with the council of heaven, and the council is like “gabriel you fucking idiot how did you lose to an object you have 23 hours before the piss drrroplets hit the fucking earth you lose gods most special boy award and you die. go fuck up that machine if you wanna live.”

GREED

greed is the fourth layer of hell, and the punishment is to push rocks up mountains in the hottest of deserts like sisyphus. speaking of sisyphus, like minos, sisyphus was the king of the greed layer. sisyphus was tired of heavens rule over hell, and when god disappeared out of nowhere, all the angels left hell in order to figure out what to do in heaven. this left everything in hell unsupervised, and in this time minos started the lust renaissance and sisyphus started the greed insurrection. king sisyphus gathered all the husks in greed in order to create an army. once everything was settled in heaven and the council was formed, the angels. came back down, saw all this bullshit happening and decided to stop it. sisyphus led a war against heaven, and although his army had more numbers, the angels were more trained. sisyphus lost the war and gabriel decapitated him.

WRATH

wrath is the fifth layer of hell, and the punishment is to fight for air in the ocean Styx. the water you see in 5-2: WAVES OF THE STARLESS SEA is not water. those are bodies. in that level, we fight a ferryman. the ferrymen are former humans that take the souls of the damned to their respective layers using the ferryman’s very cool ass boat. nothing much is left to say about wrath. you do get to fight a leviathan which is cool.

HERESY

heresy is the sixth layer of hell, and the punishment is burning alive. same as wrath, nothing much to say, really. no events or silly little guys are connected to this level. at least i think so, the miraheze wiki doesn’t say anything about this layer. like gluttony, this layer has 2 levels and we fight gabriel in the second one. while walking towards the fight, gabriel says something along the lines of “machine, your kind has fucked up all of hell. i hate you!!! >:( I AM GOING TO ULTRAKILL YOU!!!!!!”. during the fight, gabriel is very angy. gabriel infamously says “FIGHT ME LIKE AN ANIMAL, MACHINE!” which the community is very confused as to what gabriel means by that. after defeating gabriel, gabriel falls down and says “damn.” then leaves.

there yet another ad break cutscene after act 2. we first see gabriel sitting at a campfire and he is like “….. i think i’m atheist.” then he goes to the council and gets a bit wacky. he kills them. the last councilor tries to reason with gabriel, saying “B-b-but Gabriel, if you kill me, you’ll be dead within a matter of hours!”. gabriel only replies with “lol. lmao” he then cuts his head off.

—PRIME SOULS—

remember when i said there was a secret exit in gluttony? yeah, there is a door in there that only unlocks when you p rank each level in the prelude and act 1. when the door opens, there is an exit that brings you to the level “P-1: SOUL SURVIVOR” (reminder, this level is in gluttony, so we are still inside minos’ corpse.)

MINOS PRIME

we start the level with a torch and we see that minos has severe scoliosis and we walk down his spine that has like 10 turns in it. at the end of the spine vine, we enter a door on the floor and we find another fucking door inside it. it opens when you put the torch on a pedestal, and inside you encounter the FLESH PRISON. the flesh prison is a octahedral mass of flesh with one big ass mouth. the flesh prison can shoot fireballs at you, summon eyes to heal itself, and summon orbital strikes to kill you. this fight is extremely hard, and upon killing it, king minos’ prime soul is freed. a prime soul is an extremely powerful being, one of the strongest in the universe to be exact. the angels of heaven do not want these things from forming, so when the conditions are met to create a prime soul, which is someone with enough will dies, the angels lock the developing prime soul away in a prison to stop it. upon release, minos prime gives a really boring speech about our “crimes against humanity” or something idk. minos prime is one of the hardest bosses in the game, being extremely fast and dealing tons of damage. but since i am so good at this game, i can easily p rank him (on lenient difficulty). that’s about it for minos.

SISYPHUS PRIME

when you p rank each level in act 2 and defeat minos prime, a door in the level you fight gabriel in is unlocked. the level inside is P-2: WAIT OF THE WORLD. unlike minos’ level, there is more than just the prime soul fight. the level contains tons of enemies, which i won’t talk about because i’m lazy. once you get to the arena, you encounter the FLESH PANOPTICON which is a square flesh thing with multiple eyes and a mouth going all around it. like the flesh prison, the panopticon can summon eyes to heal itself, and can summon an orbital strike from the side or from the sky. but all of that doesn’t matter because sisyphus just breaks out half way through the fight. sisyphus is way taller and hotter than minos, he also way stronger. his strength can be best observed when he reaches phase 2 and grows a beard and hair. he also often says “destroy”. this is a reference to the fact that he will destroy you.

i don’t feel like writing anymore plus that’s pretty much everything. congrats if you read all of that.

will send more lore when act 3 comes out

I will read this at somepoint, lesson learned don't test Ham

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

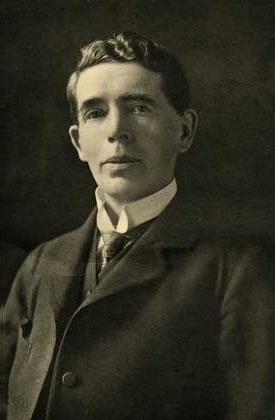

INTRO. hello, my internet really hates me with burning passion, i was really struggling earlier; i wasn’t able to like everyone’s intro posts and only managed to like a few because of it. insert nicole tv breaking down meme here. anyway here’s my boi, mino.

+ im mino + 21, haengju, baseball club + stats

BACKGROUND.

mino is a halfblood, but he doesn’t know this, in fact no one knows this. EVERYONE including himself thinks he’s a muggleborn.

basically, he is adopted by six women who lives together, they’re all “psychic” (jk just most of them are), they do tarot readings, palm readings, fortune telling etc.

mino loves all of his moms. they are the reason why he holds onto his muggle roots.

-

MAHOUTOKORO.

when he’s twelve he got invited to attend mahoutokoro and he’s one of the best students in potion studies.

he minds his own business, really, however there are children who makes fun of his broken japanese and the fact that he’s a ‘muggleborn’ doesn’t help; so to retaliate and have them off of his back, he puts a tough exterior on. he tends to get into a lot of fights due to this. if you look at him in a condescending, snobbish way then he’ll throw his fists.

“why don’t you use your fist, asshat?”

-

YEONGJI.

after finishing his studies in mahoutokoro, mino isn’t quite sure what’s next in his plans. he wants to keep in touch with his muggle roots and keep himself away from the wizarding world (due to how he hates the elitism of it is), but before he can truly turn his back on it, he’s got invited to yeongji

-

PERSONALITY.

this is still kinda spotty, still working on it. anyway on a first look you’d think he’s rv voice a really bad boy with his tattoos, piercings, and that deadpan expression; he can be guarded, but when he’s close with you he really is just a dork.

he’s soft and tender. also he’s humor is mostly just pop references, if not that then he’s just a total boomer.

CONNECTION IDEAS.

people he is batch mates with in mahoutokoro

exes?

enemies, please i beg i love this dynamics

friends

fellow haengju students?

toxic friendships?

people he ghosted or who ghosted him?

fwb?

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 Songs Tag

Tagged by the Admin Kay @jae-hyunie And I actually listened to some of the songs I hadn’t heard before on her list and ...not to say I’m stanning a new group, but :’) I’m taggin the songs for you so you can go discover the great world of what’s on my Spotify.

Rules: Answer all questions then tag 3 people you follow and 3 people that follow you that you want to get to know better

1. A song you like with a color in the title?

Gold (ft. Dean) - offonoff

2. A song you like with a number in the title?

2nd Thots - Jay Park [!!!]

3. A song that reminds you of summer?

Once Again - NCT 127

4. A song that reminds you of someone you’d rather forget?

Everglow - Coldplay [Can be applied to multiple basic boys]

5. A song that needs to be played out loud?

Prelude in E Minor - Chopin OR 30 Sexy - Rain :’)

6. A song that makes you want to dance?

Nillili Mambo - Block B [a classic, I feel srry for you if you don’t know this]

7. A song to drive to?

Mamma Mia - SF9 [Idk y...]

8. A random song you first think of?

Jealousy - Monsta X

9. A song that makes you happy?

Heart Attack - LOONA

10. A song that makes you sad?

Rain - KNK

11. A song you never get tired of?

ラビリンス - Mondo Grosso

12. A song from your past?

Oasis (ft. Zico) - Crush [Summer ‘15 litty]

13. A song that’s sexy?

Body - Mino & Yacht - Jay Park [tagging the Eng ver~]

14. A song you’d love to be played at your wedding?

L-O-V-E - Nat King Cole

15. A song you’re currently obsessed with?

Anpanman - BTS

16. A song you used to love but now hate?

Peach Scone - Hobo Johnson [Not surprisingly, it gets old fast]

17. A song you’d sing a duet with at karaoke?

Try Again - D.ear X Jaehyun

18. A song from the year you were born?

Livin’ La Vida Loca - Ricky Martin [1999, back when he was straight, still love him and his bops!]

19. A song that makes you think about life?

Pray For Me - The Weeknd & Kendrick Lamar

20. A song that has many meanings to you?

Hearing Damage - Thom Yorke [Twilight, yea]

21. A song you think everyone should listen to?

그남자 That Man - Hyunbin [Every time I karaoke]

22. A song by a group you still wish was together?

What Am I To You - History [listen to this if you have not or fuk off]

23. A song that makes you want to fall in love?

Liar Liar - OhMyGirl

24. A song that breaks your heart?

Emergency Room - [performed by] JJY

25. A song with amazing vocals?

Think About You - Jun.K [Not a ballad or anything, but I just love his voice] AND Timeless - NCT U

26. A song with amazing rap?

Hit Me - MOBB

27. A song that makes you smile?

Because of You - Taeil

28. A song that makes you feel good about yourself?

Baby Don’t Stop - NCT U :’) & Cereal (ft. Zico) - Crush [Zico lukin a whole qt]

29. A song that you would dedicate to you and your best friend/mutual/someone close to you?

I Will Always Love You - Dolly Parton

30. A song that reminds you of yourself?

365 Fresh - Triple H

I’ll tag recents @nakamoto-papoyaki @aysuh1009 n @nsfw-nct-svt

and active peeps @potato-queen7 @i-need-jisoos-christ @ratchet-sebooty

#yea i clowned u at the end#tag#the one about tagging 3 followers who i wanna get to know doesn't make sense bc then i'd b following them already???

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greece and the heroic age

Origen griego de los filisteos

[...] And the influence of Egypt can be traced in the Cretan culture of the time. The Philistines who settled in southern Palestine are now supposed to have been colonists from Crete; and remains found in Sicily and Spain testify that the Island of Minos sent products and offshoots of its civilisation far to the west. [...]

[...]

Minoa was an ancient name of Gaza. The same name, in Amorgos, Siphnos, and Paros, is a record of Cretan rule over the Aegean islands.

Inicio de la civilización griega y los poemas homéricos

The rise of a civilisation on Greek soil, very similar to Cretan, and undoubtedly under Cretan influence, began probably in the sixteenth century and lasted till the end of the twelfth. Its records are monuments of stone which have remained for more than three thousand years above the face of the earth, or have been brought to light by the spade; and the objects of daily use and luxury which were placed in the houses of the dead and have been unearthed, chiefly in our days, by the curiosity of Europeans seeking the origins of their own civilisation. And for the later stage of this period we have the Homeric poems.

Tirinto y los cíclopes

Tiryns was the older of the two fortresses, and had played its part in the earlier epoch before the Aegean peoples had yet emerged from the stone age. It stands on a long low rock about a mile and a half from the sea, and the land around it was once a marsh. From north to south the hill rises in height, and was shaped by man’s hand into three platforms, of which the southern and highest was occupied by the palace of the king. But the whole acropolis was strongly walled round by a structure of massive stones, laid in regular layers but rudely dressed, the crevices being filled with a mortar of clay. This fashion of building has been called Cyclopean from the legend that masons called Cyclopes were invited from Lycia to build the walls of Tiryns. The main gate of entrance, on the east side, was approached by a passage between the outer wall of the fortress and the wall of the palace; and the right, unshielded side of an enemy advancing to the gate was exposed to the defenders on the castle wall. On the west side there was a postern, from which a long flight of stone steps led up to the back part of the palace. But one curious feature in the castle of Tiryns sets it apart from all the other ancient fortresses of Greece. On the south side the wall deepens for the purpose of containing store-chambers, the doors of which open out upon covered galleries, also built inside the wall, and furnished with windows looking outward.

Helena como pretexto

It was probably at the beginning of the twelfth century that the Achaeans made ready a great expedition to exterminate the power which was the chief obstacle to eastward expansion (It is quite possible that the motive which the poets assigned for the Trojan War —to recover Helen, the wife of Menelaus, king of Sparta, carried off by Paris, son of Priam, — had some historical basis; but if such an incident occurred, it served only as a pretext for the war.). It is uncertain how far the Greek states of the time can be described as a federation or an empire, but most of them recognized the supremacy of Mycenae, and there seems no reason to doubt that the Achaean king of Mycenae, whose name was Agamemnon, son of Atreus, succeeded in enlisting the co-operation of the chief kings and princes of northern as well as southern Greece; it looks, indeed, as if the Achaean lords of Phtia and Thessaly —the country from which the Argo sailed—had a particular interest in the enterprise. All sailed to the plain of Troy. The peoples of the west coast of Asia, including the Lycians, all rallied to the help of Priam. It was a war between both sides of the Aegean sea. According to the tradition of the poets the siege lasted nine years; and, however it came about, Priam’s city was destroyed. Its fall was the necessary prelude to the opening of the Propontis and the Euxine sea to Greek enterprise, and Greek colonization on the eastern coasts and islands of the Aegean would soon begin. The hill of Troy would be again inhabited, but it would be of small importance, little more than a place of famous memories.

The Rape of Helen by Tintoretto (1578–1579, Museo del Prado, Madrid); Helen languishes in the corner of a land-sea battle scene.

The homeric poems

The later period of the heroic age, its manners of life, its material enviroment, its social organisation, its political geography, are reflected in the Homeric poems. Although the poets who composed the Iliad and the Odissey probably did not live before the ninth century, they derived their matter from older lays which must have belonged to to the generations inmediately succeeding the Trojan War. After the age of bronze had passed away, and the conditions of life and the political shape of the greek world had been utterly changed, it would have been impossible for any one, however imaginative, —unless he were a scientific antiquarian with abundance of records at his command,—to create a consistent picture of a vanished civilisation. And the picture which Homer presents is a consistent picture, closely corresponding, in its main features and in remarkable details, to the evidence which has been recently recovered from the earth and described in the foregoing pages. The Homeric palace is built on the same general plan as the palaces that have been found Mycenae and Tiryns, at Troy and in Boetia.

The equipment of the Homeric heroes and the man-screening Homeric shield receive their best illustration from Mycenaean gems and jars. The blue inlaid frieze in the vestibule of the hall of Tiryns proves that the poet’s frieze of cyanus in the hall of Alcinous was not a fancy; and he describes as the cup of Nestor a gold cup with doves perched on the handles, such as one which was found in a royal tomb at Mycenae.

The subjects wrought on the shield which the master-smith made for Achilles may be illustrated by works of art found at Mycenae and in Crete. The shield, wrought in bronze, tin, silver, and gold, is round and has a ringed space in the centre, encompassed by three concentric girdles. In the middle is the earth, the sea, and the heaven, with “the unwearied sun and the moon at her full, and all the stars wherewith heaven is crowned”. The subject of the first circle is Peace and War. Here are scenes in a city at peace —banquets, bride borne through the streets by torchlight to their new homes, the elders dealing out justice; there is another city besieged, and scenes of battle. The second circle shows scenes from country-life at various seasons of the year: ploughing in spring, the ploughman drinking a draught of wine as he reaches the end of the black furrow; a king watching reapers reaping in his meadows, and the preparations for a harvest festival; a bright vintage scene, “young men and maids bearing the sweet fruit in wicker baskets,” and dancing, while a boy plays a lyre and sings the song of Linus; herdsmen with their dogs pursuing two lions which had carried of an ox from the banks of a sounding river; a pasture and shepherds’ huts in a mountain glen. The whole was girded by the third, outmost circle, through which “the great might of the river Oceanus” flowed —rounding off, as it were, the life of mortals by its girdling stream.

The whole conception is due to the imagination of the poet, but similar scenes of Peace and War were depicted by the artists of the Aegaen; as for instance, on the Cretan plaques (which probably adorned the cover of a chest of cypress-wood) on which we saw a city represented, and on a vase of steatite decorated by a picture of what is probably a harvest festival. The siege is illustrated by the scene of the leaguered city on the silver beaker (above, p. 25); and dagger blades discovered at Mycenae show brilliant examples of the art of inlaying on metal.

The art of writing, too, is mentioned in the Iliad, in the story of Bellerophon, who carries from Argos to Lycia “deadly symbols in a folded tablet”. The fact, which was doubted till a few years ago, that writing was practised in the heroic age, shows that the poet was guilty of no anachronism.

There is indeed on striking difference in custom. The Mycenaen tombs reveal few traces of the habit of burning the dead, which the Homeric Greeks invariably practised; while, beyond what is implied in a single mention of embalming, the poems completely ignore the practice of burial. In later times both customs existed in Greece side by side. The explanation of the discrepancy is still uncertain.

Heroic minstrelsy was probably an old institution in Greece, and in the twelfth century lays commemorating the Trojan War were sung throughout Greece. The glorification of Achilles and other features of the Iliad point to northern Greece, where was the kingdom of Achilles in Phtia, as the home of one of these early minstrels. In southern Greece too, in the royal palaces of Mycenae and Argos, Sparta and Pylos, lays of Troy, which would long afterwards inspire the epic poetry of Homer, must have been sung.

La propiedad familiar y el sentimiento religioso de enterrar a los muertos

The importance of the family is most vividly shown in the manner in which the Greeks possessed the lands which they conquered. The soil did not become the private property of individual freemen, nor yet the public property of the whole community. The king of the tribe or tribes marked out the whole territory into parcels, according to the number of families in the community; and the families cast lots for the estates. Each family then possessed its own estate; the head of the family administered it, but had no power of alienating it. The land belonged to the whole kin, but not to any particular member. The right of property in land seems to have been based, not on the right of conquest, but on a religious sentiment. Each family buried their dead within their own domain; and it was held that the dead possessed for ever and ever the soil where they lay, and that the land round about a sepulchre belonged rightfully to their living kinsfolk, one of whose highest duties was to protect and tend the tombs of their fathers.

Asignación de nombre a pueblos y el grupo Iónico

[…]A number of cities or settlements, which have no political union and are merely associated together by belonging to the same race and speaking the same tongue, do not generally choose themselves a common name. It rather happens that when they get a common name it is given to them by strangers, who, looking from the outside, regard them as a group and do not think of the differences of which they are themselves more vividly conscious. And it constantly happens that the name of one member of the group is, by some accident, picked out and applied to the whole. Thus it befell that the Aeolian and not the Achaean name was selected to designate the northern division of the Greek settlements in Asia; just as our own country came to be called not Saxony but England. The southern and larger group of colonies received the name of lāvǒnes —or Īones, as they called themselves, when they lost the letter υ. The Iavones “with flowing tunics”, who are mentioned in the Iliad in association with the Boeotians, refers to the Athenians; but the name itself, perhaps, is not Greek and was first given to the Greek colonists on Asiatic soil.

Eritras, la carmesí

[...]

Of the foundation of the famous colonies of Ionia, of the order in which they were founded, and of the relations of the settlers with the Lydian natives, we know as little as of the settlements of the Achaeans. Clazomenae and Teos arose on the north and south sides of the neck of the peninsula which runs out to meet Chios; and Chios, on the east coast of her island, faces Erythrae on the mainland—Erythrae, "the crimson," so called from its purple fisheries, the resort of Tyrian traders.[...]

Homero

[...]

The colonists carried with them into the new Greece beyond the seas traditions of the old civilisation which in the mother country was being overwhelmed by the Dorian invaders; and those traditions helped to produce the luxurious Ionian civilisation Icon which meets us some centuries later when we come into the clearer light of recorded history. And they carried with them their minstrelsy, their lays of Troy, celebrating the deeds of Achilles and Agamemnon and Odysseus. The heroic lays of Greece entered upon a new period in Ionia, where a poet of supreme genius arose, and the first and greatest epic poem of the world was created. It was probably in the ninth century that Homer composed the Iliad. His famous name has the humble meaning of "hostage", and we may fancy, if we care, that the t poet was carried off in his youth as a hostage in some local strife. Possibly he lived in rugged Chios, and he gives us a local touch when he describes the sun as rising over the sea. From him the Homerid family of the bards of Chios were sprung. He took as his main argument the wrath of Achilles leading up to the death of Hector, and wrought into his epic many other episodes derived from the old lays on the theme of Troy. Tradition made Homer the author of both the great epics, the Odyssey as well as the Iliad. Whether this is so or not, no great length of time need separate the composition of the two poems.

Many critics think that the Iliad we have is not the original Iliad of Homer, but that his poem was a much shorter work and was remoulded and expanded by succeeding poets in a way .that was not entirely to its advantage. Similar views are held about the Odyssey. This is the "Homeric question", and no agreement has yet been reached. In any case, even if the whole Iliad was not his work—and this has not been proved—Homer was the father of epic poetry, in the sense in which we distinguish an epic poem with a large argument from a short heroic lay. His work was thoroughly artificial—conscious art, as the greatest poetry always is; and it is possible that he committed the Iliad to writing." As he and his successors sang in Ionia, at the courts of Ionian princes, he dealt freely with the dialect of the old Achaean poems. The Iliad was arrayed in Ionic dress, and ultimately became so identified with Ionia that the Achaean origin of the older poetry was forgotten. The transformation was not, indeed, perfect, for sometimes the Ionian forms did not suit the metre, and Aeolian forms were used. But the change was accomplished with wonderful skill. It is probable that the Ionian poet also did much to adapt the epic material which he used to the taste and moral ideas of a more refined age. The Iliad is notably free from the features of crude savagery which generally mark the early literature of primitive peoples; only a few slight traces remain to show that there were in the background ugly and barbarous things over which a veil has been drawn. In other respects, the Ionian poets have faithfully preserved the atmosphere of the past ages of which they sung. They preserved its manners, its environment, its geography. Only an occasional anachronism slips in, which in the otherwise consistent picture can easily be detected. Unwittingly, for instance, the poet of the Odyssey allows it to escape that he lived in the iron age, for such a proverb as "the mere gleam of iron lures a man to strife" could not have arisen until iron weapons had been long in use. But he is at pains to preserve the weapons and gear and customs of the bronze age.

Homer preserved the memory of the Trojan War as a great national enterprise. The Iliad was regarded as something of far greater significance than an Ionian poem; it was accepted as a national epic, and was, from the first, a powerful influence in promoting among the Greeks community of feeling and tendencies towards national unity. The Odyssey, affiliated as it was to the Trojan legend, became a national epic too; although the scene of one-third of the story is laid in fairyland, and it has not as a whole any national significance. And, the interest awakened in Greece by the idea of the Trojan war was displayed by the composition of a series of epic poems, dealing with those events of the siege which happened both before and after the vents described in the Iliad, and with the subsequent history of some of the Greek heroes. These poems were ascribed to various obscure authors; 47 some of them passed under the name of Homer. Along with the Iliad and Odyssey, they formed a chronological series which came to be known as the Epic Cycle.

[...]

Fall of greek monarchies and rise of the republics

Under their kings the Greeks had conquered the coasts an islands of the Aegean, and had created the city-state. These were the two great contributions of monarchy to Grecian history. In forwarding the change from rural life in scattered thorps to life in cities, the kings were doubtless considering themselves as well as their people. They thought that the change would consolidate their own power by bringing the whole folk directly under their own eyes. But it also brought the king more directly under the eye of his folk. The frailties, incapacities, and misconduct of a weak lord were more noticed in the small compass of a city; he was more generally criticised and judged. City-life too was less appropriate to the patriarchal character of the Homeric "shepherd of the people." Moreover, in a city those who were ill-pleased with the king's rule were more tempted to murmur together, and able more easily to conspire. Considerations like these may help us to imagine how it came about that throughout the greater part of Greece in the eighth century the monarchies were declining and disappearing, and republics were taking their place. It is a transformation of which the actual process is hidden from us, and we can only guess at probable causes; but we may be sure that the deepest cause of all was the change to city-life. The revolution was general; the infection caught and spread; but the change in different states must have had different occasions, just as it took different shapes. In some cases gross misrule may have led to the vionlent deposition of a king; in other cases, if the succession to the sceptre devolved upon an infant or a paltry man, the nobles may have taken it upon themselves to abolish the monarchy. In many places perhaps the change was slower. The kings who had already sought to strengthen their authority by the foundation of cities must have sought also to increase or define those vague powers which belonged to an Aryan ruler—sought, perhaps, to act of their freewill without due regard to the Council's advice. When such attempts at magnifying the royal power went too far, the elders of the Council might rise and gainsay the king, and force him to enter into a contract with his people that he would govern constitutionally. Of the existence of such contracts we have evidence. The old monarchy lasted into late times in remote Molossia, and there the king was obliged to take a solemn oath to rule his people according to law. In other cases the rights of the king might be strictly limited, in consequence of his seeking to usurp undue authority; and the imposition of limitations might go on until the office of king, although maintained in name, became in fact a mere magistracy in a state wherein the real power had passed elsewhere. Of the survival of monarchy in a limited form we have an example at Sparta; of its survival as a mere magistracy we have an example at Athens. And it should be observed that the functions of the monarch were already restricted by limits which could be contracted further. Though he was the supreme giver of dooms, there might be other heads of clans or tribes in the state who would give dooms and judgment as well as he. Though he was the chief priest, there were other families than his to which certain priesthoods were confined. He was therefore not the sole fountain of justice or religion.

There is a vivid scene in Homer which seems to have been painted when kings were seeking to draw tighter the reins of the royal power. The poet, who is in sympathy with the kings, draws a comic and odious caricature of the "bold" carle with the gift of fluent speech, who criticises the conduct and policy of the kings. Such an episode could hardly have suggested itself in the old days before city-life had begun; Thersites is assuredly a product of the town. Odysseus, who rates and beats him, announces, in another part of the same scene, a maxim which has become as famous as Thersites himself: "The sovereignty of many is not good; let there be one sovereign, one king." That is a maxim which would win applause for the minstrel in the banquet-halls of monarchs who were trying to carry through a policy of centralisation at the expense of the chiefs of the tribes.

Where the monarchy was abolished, the government passed in the hands of those who had done away with it, the noble families of the state. The distinction of the nobles from the rest of t people is, as we have seen, an ultimate fact with which we have start. When the nobles assume the government and become the rulers, an aristocratic republic arises. Sometimes the power is won, not by the whole body of the noble clans, but by the clan to which the king belonged. This was the case at Corinth, where the royal family of the Bacchiads became the rulers. In most cases the aristocracy and the whole nobility coincided; but in others, as at Corinth, the aristocracy was only a part of the nobility, and the constitution was an oligarchy of the narrowest form. At this stage of society the men of the noble class were the nerve and sinew of the state. Birth was then the best general test of excellence that could be found, and the rule of the nobles was a true aristocracy, the government of the most excellent. They practised the craft of ruling; they were trained in it, they handed it down from father to son; and though no great men arose—great men are dangerous in an aristocracy—the government was conducted with knowledge and skill. Close aristocracies, like the Corinthian, were apt to become oppressive; and, when the day approached for aristocracies in their turn to give way to new constitutions, there were signs of grievous degeneration. But on the whole the Greek republics flourished in the aristocratic stage, and were guided with eminent ability.

The rise of the republics is about to take us into a new epoch of history; but it is important to note the continuity of the work which was to be done by the aristocracies with that which was accomplished by the kings. The two great achievements of the aristocratic age are the planting of Greek cities in lands far beyond the limits of the Aegean sea, and the elaboration of political machinery. The first of these is simply the continuation of the expansion of the Greeks around the Aegean itself. But the new movement of expansion is distinguished, as we shall see, by certain peculiarities in its outward forms,—features which were chiefly due to the fact that city-life had been introduced before the colonisation began. The beginning of colonisation belonged to the age of transition from monarchy to republic; it was systematically promoted by the aristocracies, and it took a systematic shape. The creation of political machinery carried on the work of consolidation which the kings had begun when they gathered together into cities the loose elements of their states. When royalty was abolished or put, as we say, "into commission," the ruling families of the republic had to substitute magistracies tenable for limited periods, and had to determine how the magistrates were to be appointed, how their functions were to be circumscribed, how the provinces of authority were to be assigned. New machinery had to be created to replace that one of the three parts of the constitution which had disappeared. It may be added that under the aristocracies the idea of law began to take a clearer shape in men's minds, and the traditions which guided usage began to assume the form of laws. In the lays of Homer we hear only of the single dooms given by the kings or judges in particular cases. At the close of the aristocratic period comes the age of the lawgivers, and the aristocracies had prepared the material which the lawgivers improved, qualified, and embodied in codes.

Phoenician intercourse with Greece

The Greeks were destined to become a great seafaring people. But sea-trade was a business which it took them many ages to learn, after they had reached the coasts of the Aegean; it was long before they could step into the place of the old sea-kings of Crete. For several centuries after the Trojan War the trade of the Aegean with the east was partly carried on by strangers. The men who took advantage of this opening were the traders of the city-states of Sidon and Tyre on the Syrian coast, men of that Semitic stock to which Jew, Arab, and Assyrian alike belonged. These coast-landers, born merchants like the Jews, seem to have migrated to the shores of the Mediterranean from an older home on the shores of the Red Sea. The Greeks knew these bronzed Semitic traders by the same name, Phoenikes or "red men," which they had before applied to the Cretans. This led to some confusion in their traditions. We have seen how the Cretan Cadmus and Europa were transferred to Phoenicia in the legend.

We have no warrant for speaking of a Phoenician sea-lordship in the Aegean. The evidence of the Homeric poems shows clearly that between the commercial enterprise of the heroic age and the commercial enterprise of the later Greeks there was an interval of perhaps two hundred years or thereabouts, during which no Greek state possessed a sea-power strong enough to exclude foreign merchants from Greek seas, and trade was consequently shared by moulded to the needs of the Greek language. In this adaptation the Greeks showed their genius. The alphabet of the Phoenicians and their Semitic brethren is an alphabet of consonants; the Greeks added the vowels. They took some of the consonantal symbols for which their own language had no corresponding sounds, and used these superfluous signs to represent the vowels. Several alphabets, bring in certain details, were diffused in various parts of the Hellenic world, but they all agree in the main points, and we may suppose that the original idea was worked out in Ionia. In Ionia, at all events, writing was introduced at an early period, and was limps used by poets of the ninth century. Perhaps the earliest example of a Greek writing that we possess is on an Attic jar of the seventh century; it says the jar shall be the prize of the dancer who dances more gaily than all others. But the lack of early inscriptions is what we should expect. The new art was used for ordinary and literary purposes long before it was employed for official records. It was the great gift which the Semites gave to Europe.

Primer ejemplo de un texto griego

Importancia de la ascendencia divina

We must now see what the Greeks thought of their own early history. Their construction of it, though founded on legendary tradition and framed without much historical sense, has considerable importance, since their ideas about the past affected their views of the present. Their belief in their legendary past was thoroughly practical; mythic events were often the basis of diplomatic transactions; claims to territory might be founded on the supposed conquests or dominions of ancient heroes of divine birth.

At first, before the growth of historical curiosity, the chief motive for investigating the past was the desire of noble families to derive their origin from a god. For this purpose they sought to connect their pedigrees with heroic ancestors, especially with Heracles or with the warriors who had fought at Troy. The Trojan war was, with some reason, regarded as a national enterprise; and Heracles—who seems originally to have been specially associated with Argolis—was looked on as a national hero. The consequence was that the Greeks framed their history on genealogies and determined their chronology by generations, reckoning three generations to a hundred years.

Derivación del nombre “Helenos” y ramificación en dorios, aeolios y ionios

In the first place, it had to be determined how, the various branches of the Greek race were related. As soon as the Greeks came to be called by the common name of Hellenes, they derived their whole stock from an eponymous ancestor, Hellen, who lived in Thessaly. They had then to account for its distribution into a number of different branches. In Greece proper they might have searched long, among the various folks speaking various idioms, for some principle of classification which should determine the nearer and further degrees of kinship between the divisions of the race, and establish two or three original branches to which every community could trace itself back. But when they looked over to the eastern Greece on the farther side of 'the Aegean, they saw, as it were, a reflection of themselves, their own children divided into three homogeneous groups—Aeolians, Ionians, and Dorians. This gave a simple classification; three families sprung from Aeolus, Ion, and Dorus, who must evidently have been the sons of Hellen. But there was one difficulty. Homer's Achaeans had still to be accounted for; they could not be affiliated to Aeolians, or Ionians, or Dorians, none of whom play a part in the Iliad. Accordingly it was arranged that Hellen had three sons, Aeolus, Dorus, and Xuthus ; and Ion and Achaeus were the sons of Xuthus.55 It was easy enough then, by the help of tradition and language, to fit the ethnography of Greece under these labels; and the manifold dialects were forced under three artificial divisions.

Las Amazonas

Of the legends which won sincere credence among the Greeks, and assumed as we may say a national significance, none is more curious or more obscure in its origin than that of the Amazons. A folk of warrior women, strong and brave, living apart from men, were conceived to have dwelt in Asia in the heroic age, and proved themselves worthy foes of the Greek heroes. An obvious etymology of their name, "breastless," suggested the belief that they used to burn off the right breast that they might the better draw the bow. In the Iliad Priam tells how he fought against their army in Phrygia; and one of the perilous tasks which are set to Bellerophon is to march against the Amazons. In a later Homeric poem, the Amazon Penthesilea appears as a dreaded adversary of the Greeks at Troy. To win the girdle of the Amazon queen was one of the labours of Heracles. All these adventures happened in Asia Minor; and, though this female folk was located in various places, its original and proper home was ultimately placed on the river Thermodon near the Greek colony of Amisus. But the Amazons attacked Greece itself. It was told that Theseus carried off their queen Antiope, and so they came and invaded Attica. There was a terrible battle in the town of Athens, and the invaders were defeated after a long struggle. At the feast of Theseus the Athenians used to sacrifice to the Amazons; there was a building called the Amazoneion in the western quarter of the city; and the episode was believed by such men as Isocrates and Plato to be as truly an historical fact as the Trojan war itself. The battles of Greeks with Amazons were a favourite subject of Grecian sculptors; and, like the Trojan war and the adventure of the golden fleece, the Amazon story fitted into the conception of an ancient and long strife between Greece and Asia.

Battle of the Amazons by Peter Paul Rubens

The details of the famous legends—the labours of Heracles, the Trojan war, the voyage of the Argonauts, the tale of Cadmus, the life of Oedipus, the two sieges of Thebes by the Argive Adrastus, and all the other familiar stories—belong to mythology and lie beyond our present scope. But we have to realise that the later Greeks believed them and discussed them as sober history, and that many of them had a genuine historical basis, however slender. The story of the Trojan war has more historical matter in it than any other; but we have seen that the Argonautic legend and the tale of Cadmus contain dim memories of actual events. It is quite probable that the heroic age witnessed rivalry and war between Thebes and Argos.

Wounded Amazon of the Capitol, Rome

— John Bagnell Bury

Obtenido de “A History of Greece to the death of Alexander the Great“. pps. 5-77

0 notes