#salmon of knowledge

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

The Salmon of Knowledge

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today I feast on the salmon of knowledge

#fionn#fionn the cat#and jen the human#cat#cute#kitten#cats of tumblr#fionn mac cumhaill#salmon of knowledge#fish toy#cat toys#play time

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Salmon of Knowledge (An Bradán Feasa) from Irish mythology. Pen drawing.

#salmon of knowledge#salmon#fish#irish mythology#fenian cycle#illustration#artists on tumblr#mythology#fish art

332 notes

·

View notes

Text

We were talking about salmon today down by the river, and I remembered how much I enjoyed the story of Fionn Mac Cumhaill and the salmon of knowledge as a kid.

Fionn Mac Cumhaill is a hero in Irish mythology, the leader of the band of warriors known as the Fianna, and broadly the main character of an Fhiannaíocht, or the Fenian cycle of myths. Fionn is very smart, and has an odd quirk where if he bites his thumb, he just knows things. And according to The Boyhood Deeds of Finn (one of the texts of the cycle), the reason for that is a thing that happened to him as a kid, while in the service of a poet named Finn Eces (or Finnegas).

Finnegas has been fishing in one particular pool for seven years, because there is a fish in this pool, a salmon, that holds all the knowledge in the world. (From a different story, this is because the salmon ate hazelnuts that had fallen into the well of wisdom). Finnegas wants this fish and, again, has spent seven years of his life trying to get it. And, finally, he does! He catches the salmon of knowledge, and all worldly wisdom is abruptly within his grasp. All he has to do is eat the fish.

So, naturally, he gives the fish to his assistant, the boy who would become Fionn, to cook up for him, sternly instructing him not to eat any part of the fish himself, but to bring it back to him. This is because only the first person to taste the fish will gain the knowledge, it’s lost once it goes to that person. And you might be thinking here, ah. I see where this is going.

But this is not a tale of trickery. Fionn, still called by his childhood name of Demne here, is not disloyal. He genuinely does intend to just cook the fish and bring it to his master.

What happens is, the poor kid burns his thumb on the fish while cooking it. And he does what any kid, or indeed any person, instinctively does when that happens. He shoves his thumb, still covered in fish fat, into his mouth to soothe the burn. And gets hit with all the world’s knowledge.

But he still has a job to do. He brings the now-cooked fish to his master, as instructed. But Finnegas knows just looking at him (I’m presuming because the kid looks a little wild-eyed as a result of getting slammed across the head with all the world’s wisdom) that something has happened, and rapidly asked if Fionn disobeyed him and tasted the fish. Fionn, being a decent kid, says he didn’t, but explains what did happen instead.

And Finnegas, despite losing the object of his obsession for seven years of his life … Kind of rolls with it? He figures what’s done is done, and gives the kid the rest of the fish to eat, since he might as well now.

I just love that Fionn Mac Cumhaill, one of the most badass warriors in Irish mythology, essentially gained all the world’s wisdom by accident because of the kneejerk human instinct to shove an injured finger into his mouth.

Also, whenever he needs to know something he can’t reasonably know thereafter, he has to stick his thumb back in his mouth to magically gain the knowledge.

It just. I don’t know. It really adds to his image? I enjoy it.

#mythology#irish mythology#fionn mac cumhaill#fenian cycle#salmon of knowledge#when you get magic knowledge powers by accident after sucking your burned finger by instinct#you know#as one does

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Wren Prince II - Riding the Salmon of Knowledge

#my art#sketches#bird#birb#birb art#salmon#salmon of knowledge#irish mythology#artists on tumblr#small artist#ireland#celtic#wren

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thank you for the response! What's your favorite myth or piece of folklore? I personally like the ones with selkies though I can't think of a specific one at the top of my head

Oh gosh, this one is gonna be tough. There hasn't been a piece of folklore or myth I hadn't loved.

If we are talking about themes and characters, anything where the main character is an animal, either interacting with other animals or explaining why certain animals behave in a particular way. So selkies have also been a big part of my fascination, along with mythical creatures like dragons, Nessie, and Pookas.

However, my personal favorite story in Irish Mythology to share is that of the Salmon of Knowledge, a creature featured in The Boyhood Deeds of Fionn.

Long story short, our brave young hero Fionn mac Cumhaill is the apprentice of an old poet named Finn Eces. Finn has been trying to catch a salmon in the Well of Wisdom for 7 years because eating it will mean he gains all of the world's knowledge. Once they finally catch the salmon, Fionn is sent to cook it, only to have his thumb burnt on its fat. He sucks on his thumb to alleviate the pain, only to take all the knowledge from the salmon in that one action. Finn allows Fionn to have the rest of the salmon, giving Fionn all the knowledge in the world. So, whenever Fionn finds himself in a dire situation and needs a quick bout of wisdom, he bites his thumb and all the knowledge stored inside him rushes through to give him a fool-proof plan.

#seanchaí asks#irish mythology#salmon of knowledge#literally joined the crk fandom because I thought the Fount of Knowledge was a reference to the Salmon of Knowledge

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Salmon of Knowledge sticker idea WIP Might do other Irish Mythology stuff down the line, this was fun and my first time probably drawing a fish in my entire adult life !

#ignore the coloring outside lines and lumpy lines its literally a wip#but im so excited for this sticker im thinking the orange stars will be holographic with a holographic outline around the fish#salmon of knowledge#fionn mccool#also something something I know no salmon truly looks like this but i just did an atlantic salmon with cool coloration cause like. who care#its supposed to be a special salmon im forfeiting historical and anatomical accuracy just a tiny bit

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

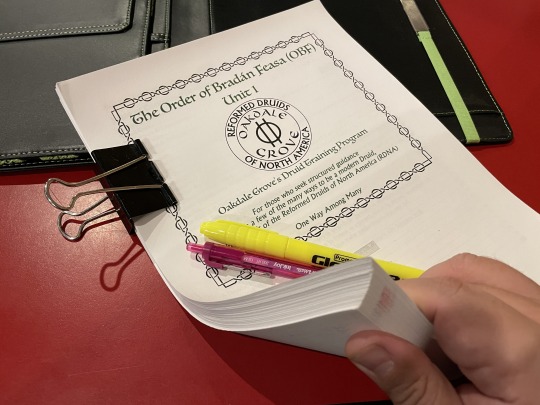

The Order of Bradán Feasa (OBF)

Unit One of an RDNA Druid training program is finally in its first draft! I started writing this in 2020, and wrote a majority of it (114 pages) that year because I wanted to have created something before the feared perception of probably contracting Covid and dying therefrom. Then once I was vaccinated, I got complacent and set the draft aside, coming back to it perhaps once a month, re-reading and revising, not really adding any new content.

In an attempt to push forward with my list of proposed topics, I started to realize I was not qualified to create content for many of them, and that I needed to do a lot more reading and learning for my own sake before continuing. Thus 2021, 2022, and much of 2023 were dedicated to reading my stack of purchased but unread books, annotating, highlighting, and cross-referencing for veracity.

I still have a lot of reading and learning ahead of me, but much of that will align with Unit Three, which hasn't been started yet. Unit Two has actually been in a draft form since 2017, and there will be an exam to go with it. This will probably be the first modern Druid training program with an exam, and it will require a 90% score or higher to pass.

What is the OBF?

The Order of Bradán Feasa is a non-clerical side order made for the Reformed Druids of North America. The name means the "Salmon of Knowledge" in Irish Gaelic, and is a reference to the myth of Finn McCool gaining all the world's knowledge when he burns himself while cooking the salmon. Any person who completes Units One and Two will be inducted to OBF and given a digital certificate indicating completion of said training program. Units One and Two would be considered sufficient training for in-person candidates to be invited to Second Order initiation in the RDNA. The optional Unit Three is the RDNA Clergy Prep Course and Grove Governance Guide (GGG), and would be considered prerequisite to ordination to the Third Order: the RDNA priesthood, in addition to existing customary requirements such as the supervised All-Night Vigil.

Completing the First Draft

While some people write novels during November for N.A.N.O.M.I.R.O. or whatever, I was suddenly inspired to get Unit One done. Over the month of November I wrote 55 new pages and revised existing content again. No, that's no novel, but writing something of (hopefully) academic quality with APA citations is a bit more meticulous, especially with this being my first "college level" type of project in about 16 years.

Members of Oakdale Grove are in the process of reviewing and annotating the first draft already. I find it easier to spot needed revisions or typos when something is in print, plus I love writing directly on drafts with an ink pen because I'm an older millennial (roars in dinosaur, lol). And I get to review and mark it up for editing with a bit of a Dark Academia aesthetic. I'm a bit shocked that Unit 1 is 169 pages, and likely to grow. We've already identified some sections that don't exist yet that need to be here. Unit 2 is much smaller. I expect Unit 3 to be smaller, as well.

The goal is for Unit 1 to go live before Beltane 2024, for Unit 2 to go live by the Autumnal Equinox of 2024, and for Unit 3 to go live by the end of 2024. That last one has the greatest uncertainty though, because I still have two important books to read, and possibly more that I haven't found yet.

See also: OBF Program Syllabus

#druidry#pagan#paganism#druid#druidism#druids#rdna#reformed#initiation#training#OBF#Order of Bradan Feasa#Salmon of Knowledge

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

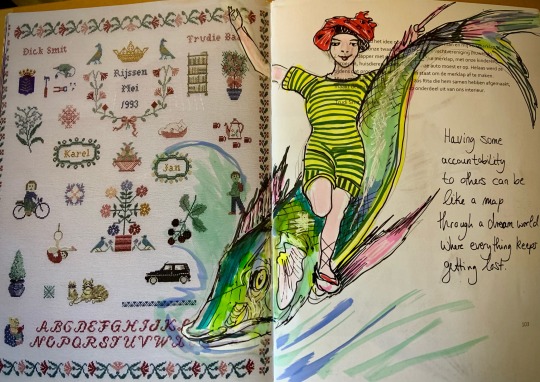

magazine doodle by J.J.

#artists on tumblr#artist's studio#drawing#sketchoftheday#illustration#sketchbook#doodle#salmon of knowledge#ink and watercolor

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bradanend is pretty much on point, but isn't quite as hunched as i'd like. If the flesh part of its design sat a little lower over the shoulders, it'd be spot on. Bradaknow are incredibly intelligent and are capable of amassing a great wealth of knowledge. So great is their intuition that they are capable of prophesising even their own deaths, something they live in fear of. Being incredibly tasty, with legends stating that to eat one is to gain it's knowledge, does nothing to ease their existential crisis. Upon breeding successfully a Bradanend's body begins to break down, it's task now complete. For as long as their fleshy hump remains, their bones will continue to animate. Caught between life and death, these pokemon trade in their potent psychic abilities for the power to manipulate soul energy, drawing power from their dead comrades. --Attack Info-- --Ability Info--

#tresto#fakemon#fakedex#saucylobster#fish#salmon#salmon of knowledge#an bradan faesa#zombie#gillman#skeleton

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

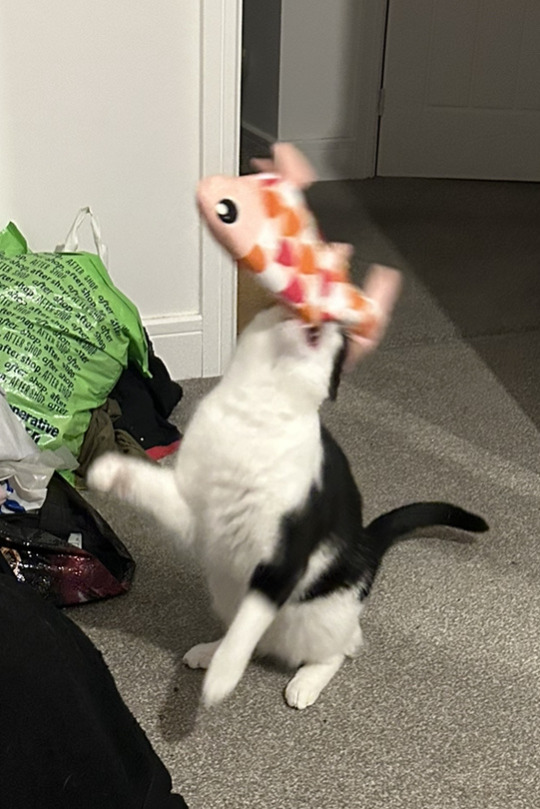

I wouldve gone ape shit for this as a kid (yes ik it is a cat toy. I played with cat and human toys ok), also why is it kinda giving Salmon Of Knowledge though...

16K notes

·

View notes

Note

idk if you’re still doing trc drabbles but I would love to read anything else you want to write about pre-canon ronsey bc you had such a gorgeous addition to my post abt them and I’m deep in my feelings for them

OMG YES I have written abt pre-canon Ronsey here and here snuck some in here, but I’ve got more just for you!!! (This got away from me lol)

Okay so Ronan and Gansey spending hours at a time getting progressively sweatier and filthier as they’re working on Monmouth Manufacturing hauling garbage out into the parking lot. Gansey has propped open as many windows as he can but it’s still like being roasted alive in a vacuum-sealed 10,000sq foot furnace, while the undersides of Ronan’s feet getting progressively blacker and filthier until he almost impales himself on a rusty nail Home Alone-style and Gansey makes him run out to the car to grab his mud boots.

And the two of them hooked up the wiring in the bathroom/laundry room/kitchen first so that they could plug in the fridge and stock it w cold water and Ronan comes back and finds Gansey just standing in front of the open fridge holding a cold bottle of water to his forehead and Gansey had taken his shirt off pretty much immediately and for once Ronan just lets himself look at his new strange and fantastic friend, shimmering in the dim heat-haze, lit otherworldly in the dim cave of Monmouth Manufacturing by the weak fridge light, his chest rising and falling from exertion, caked in sweat and grime but somehow still unsullied, boyish and starting to develop muscle from all their hard labor and Ronan’s heart bangs in his throat and he stomps away so that Gansey will hear him and the spell will be broken.

And when they finally call it quits Gansey asks Ronan if he knows of anywhere they could swim, and Ronan almost can’t answer for a second because he does know a place and the pleasure and self-consciousness at the prospect of bringing Gansey overwhelms him.

And he takes him to a watering hole in the forest and it’s not the forest from his dreams, but like Cabeswater it feels the way Ronan feels on the inside and Gansey looks around in approval and then whips off his shirt and his pants and dives right in. And Ronan has taken his shirt off plenty of times in front of Gansey already but he feels shy all of a sudden in the secluded glen, but Gansey just cocks an eyebrow at him and says, “Coming?” And Ronan realizes with a sort of settling sense of calm that he would actually follow this boy anywhere, and he strips down to his underwear and wades in.

After an hour of the two of them climbing the tree that hangs out over the water and swinging from its branches to see who can make the biggest splash, Gansey crawls out on the bank to lie down and close his eyes. When Ronan crawls out to sit beside him, bright-eyed and fresh, shaking water from his curls, he notices that Gansey’s made a friend.

“Dude, hold still. You’ve got a bee.”

And Gansey goes very, very still and Ronan hardly notices as he coaxes the bee from Gansey’s shoulder to his own hand and stands up to let it go and when he looks back Gansey has curled into a ball with his head on his knees and his arms wrapped around himself and seems to be in full-blown freak-out mode.

Ronan drops to his knees like, “Hey, hey, it’s okay. It didn’t sting you, did it?” knowing that it hadn’t stung him. But Gansey seems to be holding his breath for some reason and Ronan goes from concerned to alarmed, rubbing his back, telling him to breathe.

And Gansey lets out a shuddering, explosive breath and sucks down a gasp and all Ronan can think is to tell him a story.

“That tree,” he said, pointing, and Gansey did not move his head but his eyes followed Ronan’s finger, rolling in his head like marbles. “It’s hazel. The druids believed they had magic powers. And because the hazel trees had magic powers, anything that lived around them and ate the hazelnuts gained the tree’s power and wisdom.”

Gansey’s breathing was starting to even out a little, in gasps and starts.

Encouraged, Ronan went on. “So this guy-maybe he was a druid, but I think they were mostly women-anyway this guy caught a salmon that had been living under the hazel tree and eating the hazelnuts as they fell in the water. The guy told his apprentice to cook the salmon so that he could eat it and take the Salmon’s wisdom for himself.”

Ronan stopped. Gansey was breathing raggedly but steadily. When he finally nodded, Ronan continued.

“So the apprentice builds a fire to cook the salmon, but as it’s cooking, its skin is getting hot and bubbling up. Maybe the kid can’t resist or maybe it was an accident, but he touches it with his thumb and pops one of the little bubbles. And it burns him, because duh, hot fish oil, and he puts his thumb in his mouth.”

Here Ronan stopped again. Finally Gansey rolled his head to one side. “Well? Did the kid get the salmon’s magic powers?”

Ronan shrugged. “I don’t remember.”

Gansey snorted and his eyes slid closed.

The two of them sat like that in silence. Ronan leaned back on his arms and tipped his head back, letting his eyes puzzle out the shifting overlap of leaves high above, outlined against a dusty grey-blue sky.

Gansey’s voice sounded rusty when he finally spoke. “Sorry.”

Ronan shrugged.

“I just—“ Gansey swallowed. “Bees.”

“I get it.”

“No,” Gansey said. “You don’t.”

Ronan scoffed, but when he lolled his head to one side, Gansey was looking straight at him, pensive, a thumb pressed to his full lower lip.

“I stepped on a wasp’s nest, once.” Ronan didn’t say anything. Gansey rubbed his face against his knees. It was a curiously boyish, distracted motion. “I’m—very allergic. One or two would have put me in the hospital, but this was hundreds.” His voice strained. “I could feel them crawling all over me, stinging me—“

Ronan shuddered.

“How’d that story end?”

Gansey closed his eyes. In the glen, he looked very fragile, balanced on the cusp of physical maturity, Death draped around his shoulders like a mantle.

“I’m still figuring that out.”

That night Ronan dreamed of cures for bee stings, bright and vivid.

#ronsey#ronan lynch#gansey#richard gansey iii#trc#trc fic#the raven cycle#the raven cycle fanfic#the Salmon of Knowledge#the Fenian Cycle#so it is written#asked and answered#posty mcpostface#that string of blog tags looks fucking insane lol

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

My teenage brother and my mom just committed to having a salmon cook-off because he thinks he can make salmon better than she can and I am IMMENSELY invested

#he's actually pretty knowledgeable about cooking stuff#watches a lot of cooking shows/youtube channels#and is currently in home ec or whatever they call it these days#my mom on the other hand#is an expert who has cooked delicious salmon many a time#but my brother hasn't always loved it#so yeah this is gonna be entertaining#i really really hope they actually do this#because not only will it be immensely entertaining for me#i'll get to eat salmon#which i love

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moí Coire coir Goiriath or

'The Cauldron of Poesy'

An untitled Old Irish poem by an unknown poet written in the early 8th century (Breatnach 1981). In Irish, it is commonly known by the first line of the text: "Moí Coire coir Goiriath". The title 'The Cauldron of Poesy' was given to it centuries after it was written. The complete text of the poem, along with the Middle Irish annotations and glosses added by a later scribe, is found in the manuscript TCD MS 1337.

This poem is about the kinds of knowledge and ability required to be a great poet. It describes 3 metaphorical cauldrons found within each person. These cauldrons are vessels for different kinds of knowledge and skills. They are called Coire Érmae (the Cauldron of Progression), Coire Sofis (the Cauldron of Knowledge), and Coire Goiriath (Breatnach 1981, 1990). They can be upright (full of knowledge), inclined (half-full), or upside-down (empty), and events during a person's life can change the position of the cauldrons.

8th-9th c. bronze vessel from the Derrynaflan Hoard

This poem is frequently misinterpreted as describing some kind of metaphysical energy centers. Some people go as far as to link the cauldrons to Asian concepts like qi or chakras. The inaccurate translations used in these interpretations obscure the fascinating blend of Christian, Pagan, and possibly ancient Greek influences in this complex work of medieval Irish poetic lore.

Poetry was a complicated profession in medieval Ireland. Professional poets, known as filid, had a minimum of 7 years of formal education and were divided into 7 different grades with ánroth and ollamh being the 2 highest. In addition to writing and preforming poetry, an ollamh was required to memorize genealogies and compose satires (Carey 1997, Breatnach 1983, Breatnach 1981, eDIL). Bards were poets who lacked formal education and were considered to be of inferior grade to a fili (eDIL, MacNeill 1924).

I don't feel qualified to talk about these topics in depth, but I want to share an accurate translation of the poem and to discuss at least some of its cultural elements.

I know of 2 authoritative translations of this poem, one by P. L. Henry (1980) and one by Liam Breatnach (1981) which has some additions and corrections (Breatnach 1984, 1990, 2023). The translation of the poem I give here is almost entirely Breatnach's with the exception of a small section that I rewrote, because I found Breatnach's wording confusing. For the glosses and annotations, I included a few of Henry's translations and some additional information from other authors. My changes and additions are in purple. I chose to leave out more than half of the annotations, because there were so many they overwhelmed the poem. This did mean losing some information about the role of poets in medieval Irish society.

We don't actually know what the word goiraith means (eDIL). Henry translates it as warming, incubation, or maintenance, based on the inference that goiraith comes from gorad (heating or warming), the intransitive form of guirid (Henry 1980). This interpretation doesn't make sense semantically in the context of the poem. The gloss for goiraith translates as, "i.e. 'it has closed off great falsehood', i.e. 'near to me in every land'," (Breatnach 1981). The text of the poem indicates that the Cauldron of Goiraith is related to having knowledge of language and grammar, and to learning and knowledge in childhood (Breatnach 1981). I don't see how warming/incubation could relate to either closing off lies or knowing grammar.

In addition to not fitting the semantic context, the interpretation of goiraith = gorad = warming doesn't fit the poetic form. The 3 cauldrons form a triad in the poem, and triads in poetry are typically written using parallel structure. The names of the other 2 cauldrons, sofis (knowledge) and érmae (progression), are both nouns (Breatnach 1981, 1990), so it follows that goiraith should also be a noun. Guirid/gorad is a verb (Henry 1980). Breatnach identifies goiraith as a compound noun with the first syllable likely being gor 'warm.' He suggests that goiraith might mean something like 'raw material' but stresses that this translation is "speculative in the extreme; the only thing that we can be reasonably sure of is that it has to do with the initial stages of study" (Breatnach 1981).

Old Irish glossary for this post:

Amairgen: mythical ollamh of ancient Ireland

ánroth: the second highest rank of fili (eDIL)

bairdne: bardic craft or metre, a type of poetry considered inferior to the work of a fili (eDIL)

Éber and Donn: mythical Irish kings

Érmae: progression (Breatnach 1990) or motion (Henry 1980)

fili (pl filid): a professional poet with at least 7 years of formal education (Breatnach 1983)

imbas: poetic inspiration or prophetic knowledge which poets (filid) obtained through magical or supernatural means (eDIL, Carey 1997)

ollamh: the highest rank of fili (eDIL)

raind: verses of poetry? (cf eDIL rann)

síd: fairy mound (eDIL)

túath: group of people or territorial unit (eDIL)

(I apologize for the formatting. I can't figure out how format this nicely on tumblr.)

'The Cauldron of Poesy' translated by Liam Breatnach:

Mine is the proper Cauldron of Goiriath,(1) warmly God has given it to me out of the mysteries of the elements;(2) a noble privilege which ennobles the breast is the fine speech which pours forth from it.(3) I being white-kneed, blue-shanked,(4) grey-bearded Amairgen, let the work(5) of my goiriath in similes and comparisons be related - since God does not equally provide for all, inclined, upside-down (or) upright- no knowledge,(6) partial knowledge(7) (or) full knowledge,(8) in order to compose poetry for Éber and Donn with many great chantings,(9) of masculine, feminine and neuter,(10) of the signs for double letters, long vowels and short vowels, (this is) the way by which is related(11) the nature of my cauldron.(12) 1 goriath, i.e. 'it has closed off great falsehood', i.e. 'near to me in every land'. 2 Well has God given it to me out of the mysteries of the elements, or 'that naming which ennobles' is a raw instrument which He has granted to me out of the mysteries of the elements. 3 which pours forth poetry from it. 4 a tattooed shank, or who has the blue tattooed shank. 5 What my cauldron does is the relation of poetry on which there are said to be many forms, i.e. white and black and speckled, or the colour of praise on praise. 6 when it is upside-down, i.e. in foolish people. 7 inclined, i.e. in those who practice bairdne and raind. 8 when it is supine, i.e. in ánroth's of knowledge and poetic art. 9 with numerous displays out of the many 'great seas' of poetry, i.e. many chantings of poetry. 10 Old Irish had 3 grammatical genders. 11 This is the law which I relate about them, or it is the declaration by which poetry is related. 12 This is the function of my cauldron. I acclaim the Cauldron of Knowledge where the law of every art is set out as a result of which prosperity increases(1) which magnifies(2) every artist in general which exalts a person(3) by means of an art. 1 It confers increase of wealth on everyone. 2 'It makes great of' every art in general, or it generally 'makes great of' him who has that skill. 3 It gives exaltation to persons together with granting something to them, or his art exalts every person.

Where is the source of poetic art in a person; in the body or in the soul?

Some say in the soul since the body does nothing without the soul. Others say in the body since it is inherent in one in accordance with physical relationship, i.e. from one's father or grandfather,(1) but it is more true to say that the source of poetic art(2) is and knowledge is present in every corporeal person(3), save that in every second person it does not appear; in the other it does.

1 a fili only had full status (honor-price) if his father or grandfather was a fili (Corthals 2014). 2 of bardic art. 3 that it is in the body.

What does the source of poetic art and every other knowledge consist of? Not difficult; three cauldrons are generated in every person, i.e. the Cauldron of Goiriath and the Cauldron of Progression and the Cauldron of Knowledge.

The Cauldron of Goiriath,(1) it is that which is generated upright in a person from the first; out of it is distributed knowledge to people in early youth.

The Cauldron of Progression, then, after it has been converted(2) it magnifies; it is that which is generated on its side in a person.

The Cauldron of Knowledge, it is that which is generated upside down, and out of it is distributed(3) the knowledge of every other art besides poetic art.

1 a cauldron in which 'great falsehood' has been 'closed off'. 2 Afterwards, after being turned over, it magnifies a person. 3 measured.

The Cauldron of Progression,(1) then, in every second person it is upside down, i.e. in ignorant people. It is on its side in those who practice bairdne and raind. It is upright in the ánroth’s of knowledge and poetic art.(2) And the reason, then, why everyone else does not practice at that same stage is because the Cauldron of Progression is upside down in them until sorrow or joy converts it.

How many divisions are there of the sorrow which converts it? Not difficult; four: longing,(3) grief,(4) and the sorrow of jealousy,(5) and exile for the sake of God,(6) and it is internally that these four make it upright,(7) although they are produced from outside.

1 a cauldron 'which turns over afterwards' in him. 2 the ollam of bardic art. 3 for his father. 4 for friends (Henry 1980). 5 after cuckolding. 6 on account of the extent of his sins. 7 it is out of its interior that these four convert the cauldron, although they are put into it from outside.

There are, then, two divisions of joy through which it is converted into the Cauldron of Knowledge, i.e. divine joy and human joy.

As for human joy, it has four divisions: (i) the force of sexual longing, and (ii) the joy(1) of safety and freedom from care, plenty of food and clothing until one begins bairdne,(2) and (iii) joy at the prerogatives of poetry after studying it well, and (iv)* joy(3) at the arrival of imbas which the nine hazel trees of fine fruit at Segais(4) in the síd’s collect and which is sent upstream(5) along the surface of the Boyne, as extensive as a ram’s fleece(6), swifter than a racehorse, in the middle of June once every seven years.*

1 after (recovering from) sickness. 2 until he practices poetry. 3 at the coming of imbas along the Boyne or the Graney, ie a bubble which the sun cause on the plants, and whoever consumes them will have an art. 4 Segais is a well at Síd Neachtain which is the source of the River Boyne according to the Dindsenchas (Gwynn 1913). 5 Possibly referring to the hazel nuts falling into the well and being eaten by salmon. See discussion on imbas below. 6 ('extensive as a ram's fleece' refers to the surface area of the river covered). (A ram’s fleece being the largest size of fleece) *Division (iv) is the section of the translation I altered.

Divine joy, moreover, is the coming of divine grace to the Cauldron of Progression, so that it converts it into the upright position, as a result there are people who are both divine and secular prophets and commentators(1) both on matters of grace and of (secular) learning, and they then utter godly utterances and produce the corroborations(2), and their word are maxims and judgments, and they are an example for all speech. But it is from outside that these make the cauldron upright,(3) although they are produced internally.

1 (ie people versed in both secular and ecclesiastical learning) as were Cumain, etc. Colmán mac Lénin and Colum Cille. 2 (that is, commentaries confirming the truth of Scripture (Breatnach 2023)). 3 it is from outside that these 'are handed over’ into his cauldron. although they are produced on the inside, i.e. it is outside the person that the divisions of enlightenment 'operate' the converting of the cauldron, while composing poetry (?) i.e. the performing of their deeds caused the converting of the cauldron.

Concerning that, what Néde mac Adnai said: I acclaim the Cauldron of Progression with understandings of grace with accumulations of knowledge with strewings of imbas, (which is) the estuary of wisdom the uniting of scholarship the stream of splendor the exalting of the ignoble(1) the mastering of language quick understanding the darkening of speech the craftsman of synchronism the cherishing of pupils, where what is due is attended to where senses are distinguished where one approaches meanings(2) where knowledge is propagated where the noble are enriched where he who is not noble is ennobled, where names are exalted(3) where praises are related by lawful means with distinctions of ranks with pure estimations of nobility with the fair speech of wise men with streams of scholarship, a noble womb in which is cooked the basis of all knowledge(4) which is set out according to law which is advanced to after study which imbas quickens(5) which joy converts which is revealed through sorrow; it is an enduring power whose protection does not diminish. I acclaim the Cauldron of Progression. 1 ‘Its essence raises up' the ignoble people to make them of noble status ie with regard to equal honor-price. 2 Many varieties of knowledge are approached in it, i.e. tales and genealogies. 3 It gives exaltation to the names of the people to whom praises are made if they are uttered according to lawful means. 4 The imbas of the Boyne which is distributed lawfully afterwards. 5 The imbas of the Boyne or the Graney moves the cauldron.

What is the Progression? Not difficult; an artistic* ‘noble-turning’(1) or an artistic 'after-turning'(2) or an artistic course, ie it confers knowledge(3) and status and honour after being converted. *The MS has sai here, Breatnach tentatively interprets this as soí (artistic) 1 The 'conversion of knowledge’ to that which it has not done before is noble. 2 or 'which reverts afterwards' to that which it has done. 3 poetry or eloquence.

The Cauldron of Progression it grants, it is granted it extends, it is extended it nourishes, it is nourished(1) it magnifies, it is magnified it requests, it is requested of(2) it acclaims, it is acclaimed it preserves, it is preserved it arranges, it is arranged it supports, it is supported. Good is the source of measuring,(3) good is the acquisition of speech,(4) good is the confluence of power,(5) which builds up strength. It is greater than any domain, it is better than any patrimony, it brings one to wisdom,*(6) it separates one from fools.

1 He feeds a person together with (his) retinue, and he is fed together with (his) retinue, i.e. he provides entertainment and entertainment is provided for him. 2 He makes demands on the members of the túath, and entreaties are made to him for their forcibly removed cattle'. (This gloss refers to the function of the poet in enforcing claims on behalf of the members of his túath outside the boundaries of the túath, his means of enforcement being satire, and to the entitlements due to him for performing this function (Breatnach 1984).) 3 Good is the cauldron out of which one measures by letter and verse-foot. 4 Good is the cauldron in which is the 'fire of knowledge' 5 Good is the cauldron out of which all this is obtained. *Henry translates this line as 'it brings to (the grade of) a scholar'. 6 the same honour-price as a king. This gloss refers to the fact that an ollamh was considered worthy of the same honor-price as a king in medieval Ireland (Carey 1997).

Discussion: Divine Joy, Imbas, and Philosophy

An early 8th century composition date (Breatnach 1981) means that this poem was written a few centuries after the arrival of Christianity to Ireland. That the original author was Christian can be seen in the description of the divine joy that turns the Cauldron of Progression. Divine grace and divine prophets are common themes in Christian writing. The consistent use of God singular (Dia) as a proper noun and the mention of the body and soul as 2 separate entities also indicate a Christian author (cf Henry 1980). The mentions of imbas, however, suggest the acceptance of continued Pagan magic practices by the Christian author (Carey 1997).

The early 10th c. text Cormac’s Glossary clearly marks imbas as Pagan magic when it condemns the ritual of imbas forosnai for requiring offerings to Pagan gods (Russell 1995, Carey 1997). This attitude is in sharp contrast with earlier Irish texts like Bretha Nemed where having imbas forosnai is considered a required qualification for an ollamh (Carey 1997). 'The Cauldron of Poesy' is, perhaps, a middle ground between a pre-Christian norm, and later Christian intolerance. It categorizes imbas as one of the 4 kinds of human joy that can turn the Cauldron of Progression, something which is beneficial for an ollamh to have but not essential (Carey 1997).

How did a medieval poet obtain the supernatural knowledge known as imbas? In the ritual described in Cormac’s Glossary, the poet chews on raw meat, chants over his hands, and then sleeps with his palms against his face (Russell 1995), a practice which bears no resemblance to the one hinted at in 'The Cauldron of Posey'. Some modern scholars have questioned whether Cormac actually knew what he was talking about (Carey 1997). Some later medieval sources are more useful for making sense of the the arrival of imbas on the River Boyne mentioned in the poem.

The Dindsenchas about the River Shannon mention 9 hazels growing around the well of Segais which is the source of 7 rivers. The hazels, which are associated with poetic wisdom, drop their nuts into the water. The nuts are then eaten by salmon (Gwynn 1913). The 12th c. Macgnimartha Find explicitly connects eating salmon from the Boyne to gaining imbas. It tells how Finn Éces spent 7 years by the Boyne waiting to catch a salmon that would grant him knowledge only to have his student Fionn mac Cumhaill accidentally eat a bit of the fish while cooking it and gain the knowledge of imbas forosnai instead (Carey 1997). Salmon swim upstream to breed during the spring and summer in Ireland (Inland Fisheries Ireland) which might explain why the poem describes imbas as being sent upstream in the middle of June.

Based on these sources, it appears the ritual for gaining the joy of imbas was simply: go to the Boyne on the summer solstice of the 7th year, catch a salmon, and eat it. How you identified the correct year, I don't know, but perhaps it was linked to the 7 years of a fili's education.

Although the joys which turn the Cauldron of Progression could be either Christian or Irish Pagan, the metaphor of the cauldrons appears to have a completely different origin. The 3 cauldrons serve as vessels for different things. Coire Goiriath, given out of the (natural) elements, contains basic childhood knowledge. Coire Érmae (Progression) contains the capacity to expand a person's knowledge based on experiences of joy or sorrow. Coire Sofis (Knowledge) contains advanced knowledge of the arts. This setup bears a striking resemblance to Aristotle's 3-part concept of the human soul. Aristotle divides the soul into (1) the nutritive soul, possessed by all living things, which contains the most basic faculties necessary for survival, (2) the animal soul, possessed by animals and humans, which contains faculties for sensation and movement, and (3) the rational soul, possessed by humans, which contains faculties for thinking and logic (Corthals 2014).

The similarities between Aristotle and the cauldrons go beyond just dividing the inner workings of humans into 3 categories of increasing intellectual complexity. Coire Érmae is moved by experiences of joy or sorrow, much like Aristotle's animals, with their animal souls, move in response to desires to experience pleasure or avoid pain (Corthals 2014, Aristotle 350 BCE/1907). Furthermore, the sensations experienced by the animal soul that lead to pleasure or pain are caused by external forces much like the sorrows that move the cauldron are caused by external forces (Aristotle 350 BCE/1907).

If Coire Goiriath is inspired by Aristotle's nutritive soul, this might explain the enigmatic glosses: 'it has closed off great falsehood', i.e. 'near to me in every land'. As the nutritive soul was only concerned with basic survival, Aristotle believed it was incapable of producing lies (Aristotle 350 BCE/1907), hence the Cauldron of Goiriath would be incapable of producing falsehood. As for the second gloss, a person always has their basic survival instincts with them, no matter where they go. The decision to replace types of souls with types of cauldrons might have been made by an Irish poet who was looking for imagery that was more familiar to their audience. (See Henry 1980 for other examples of cauldrons used in medieval Irish literature.)

While it seems unlikely than an 8th c. Irish poet actually read Aristotle, the poet may have had access to other works inspired by Aristotle's ideas. For example, the 7th c. writer Virgilius Grammaticus describes a 3-part soul that seems to have been derived from Aristotle. Virgilius might have been Irish, and even if he wasn't, parts of his writing definitely made it to Ireland (Corthals 2014).

In addition to the religious and philosophical elements I've discussed, 'The Cauldron of Posey' also contains quite a bit of material on secular Irish society with topics including the education of poets, the status of poets, and the role of poets in settling disputes (Breatnach 1981, 1984, Corthals 2014). In the section on divine joy, it appears the poet is trying to create unity between secular and ecclesiastic views of learning (Breatnach 1981). These things are well outside my area, but I do want to point out that there is more to this poem than religion.

'The Cauldron of Posey' contains an intriguing mix of Christian and Pagan, secular and ecclesiastic, foreign and native, cooked together into a single harmonious poem. It shows us that the transition from Pagan to Christian was a gradual process with elements of both existing side by side. It also shows us that religion was just one piece of Ireland’s cultural history, and if we focus exclusively a search for spiritual meaning, we risk missing out on the rich cultural details.

Bibilography:

Aristotle. (1907). De Anima (R. D. Hicks, Trans.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published ca. 350 BCE) https://archive.org/details/aristotledeanima005947mbp/page/n7/mode/2up

Breatnach, L. (1981). The Cauldron of Poesy. Ériu, 32(1981), 45-93. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30007454

Breatnach, L. (1984). Addenda and Corrigenda to 'The Caldron of Poesy' (Ériu xxxii 45-93). Ériu, 35(1984), 189-191. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30007785

Breatnach, L. (1990). On the Citation of Words and a Use of the Neuter Article in Old Irish. Ériu, 41(1990), 95-101. http://www.jstor.com/stable/30006290

Breatnach, L. (2023). Varia 1. Proclitic mis. 2. fírad. 3. Further to In Coire Érmae, ‘The Caldron of Poesy’. Celtica, 35(2023), 66-77. https://journals.dias.ie/index.php/celtica/article/view/6/5

Breatnach, P. (1983). The Chief's Poet. Proceedings of the RIA: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, 83C(1983), 37-79. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25506096

Carey, J. (1997). The Three Things Required of a Poet. Ériu, 48(1997), 41-58. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30007956

Corthals, J. (2014). Decoding the 'Caldron of Poesy'. Peritia, 24-25(2013-14), 74-89. https://www.scribd.com/document/721674860/Decoding-the-Caldron-of-Poesy

eDIL 2019: An Electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language, based on the Contributions to a Dictionary of the Irish Language (Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1913-1976) (www.dil.ie 2019). Accessed on 6/30/24

Gwynn, E. (1913). Royal Irish Academy Todd lecture series: The Metrical Dindshenchas Part III (Vol. X). Hodges, Figgis, & Co., LTD. https://archive.org/details/toddlectureserie10royauoft/page/n3/mode/2up

Henry, P.L. (1980). The Cauldron of Poesy. Studia Celtica, 14/15(1979/1980), 114-128. https://www.seanet.com/~inisglas/henrycauldronpoesy.pdf

MacNeill, E. (1924). Ancient Irish Law. The Law of Status or Franchise. Proceedings of the RIA: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, 36(1921 - 1924), 265-316. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25504234

Russell, P. (1995). Notes on words in early Irish glossaries. Etudes Celtiques, 31(1995), 195-204. https://www.persee.fr/doc/ecelt_0373-1928_1995_num_31_1_2070Russell 1995

#old irish#middle irish#early medieval#sorry about the cauldron puns#poetry#translation problems#8th century#irish history#the salmon of knowledge

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

I happy to share always. Is tasty to bite and it flaps a lot

Hi Ricky do you like my salmon? I will share it with you if you like. -Fionn the cat

Yes your salmon so cool i playing with it

#fionn the cat#and jen the human#kitten#cats of tumblr#cute#cat#fionn#tuxedo cat#black and white bicolour#fionn mac cumhaill#salmon of knowledge

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just found out salmonberries from Stardew Valley are fucking real…this changes everything.

7 notes

·

View notes